Vehicle Sideslip Angle Redundant Estimation Based on Multi-Source Sensor Information Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

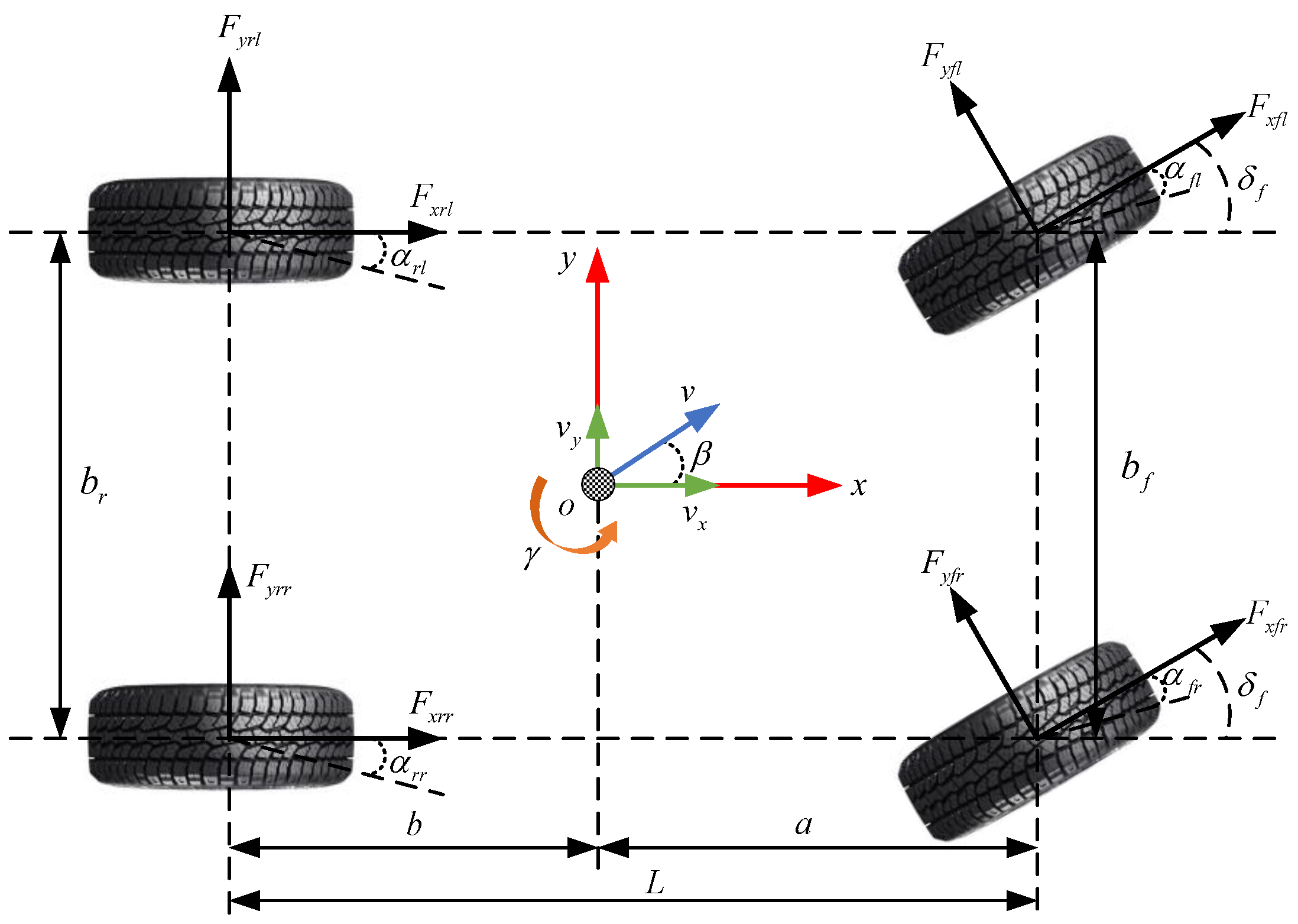

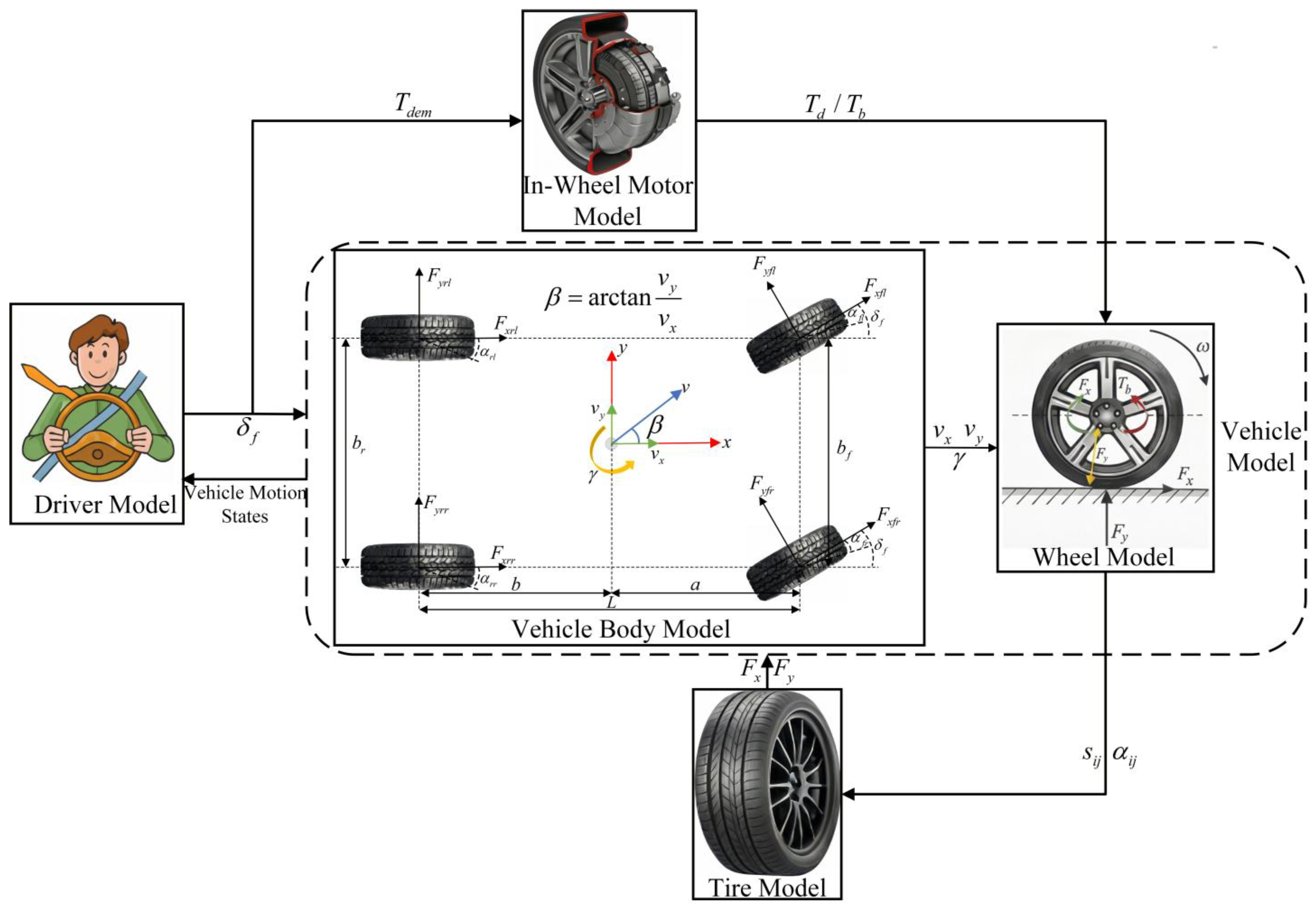

2. Vehicle Dynamics Model

2.1. Vehicle Body Dynamics Model

- (1)

- Road slope and unevenness are neglected; the road surface is assumed to be perfectly flat and horizontal, eliminating motion along the z-axis.

- (2)

- The effects of suspension system are ignored; vertical, roll, and pitch motions, as well as their coupling effects on other motions, are neglected.

- (3)

- Steering system delay is ignored, and only the front wheels steer with the same angle for both the left and right wheels.

- (4)

- Air resistance and tire torque effects are neglected, and all four wheels are assumed to be identical in their mechanical properties and tire dynamics.

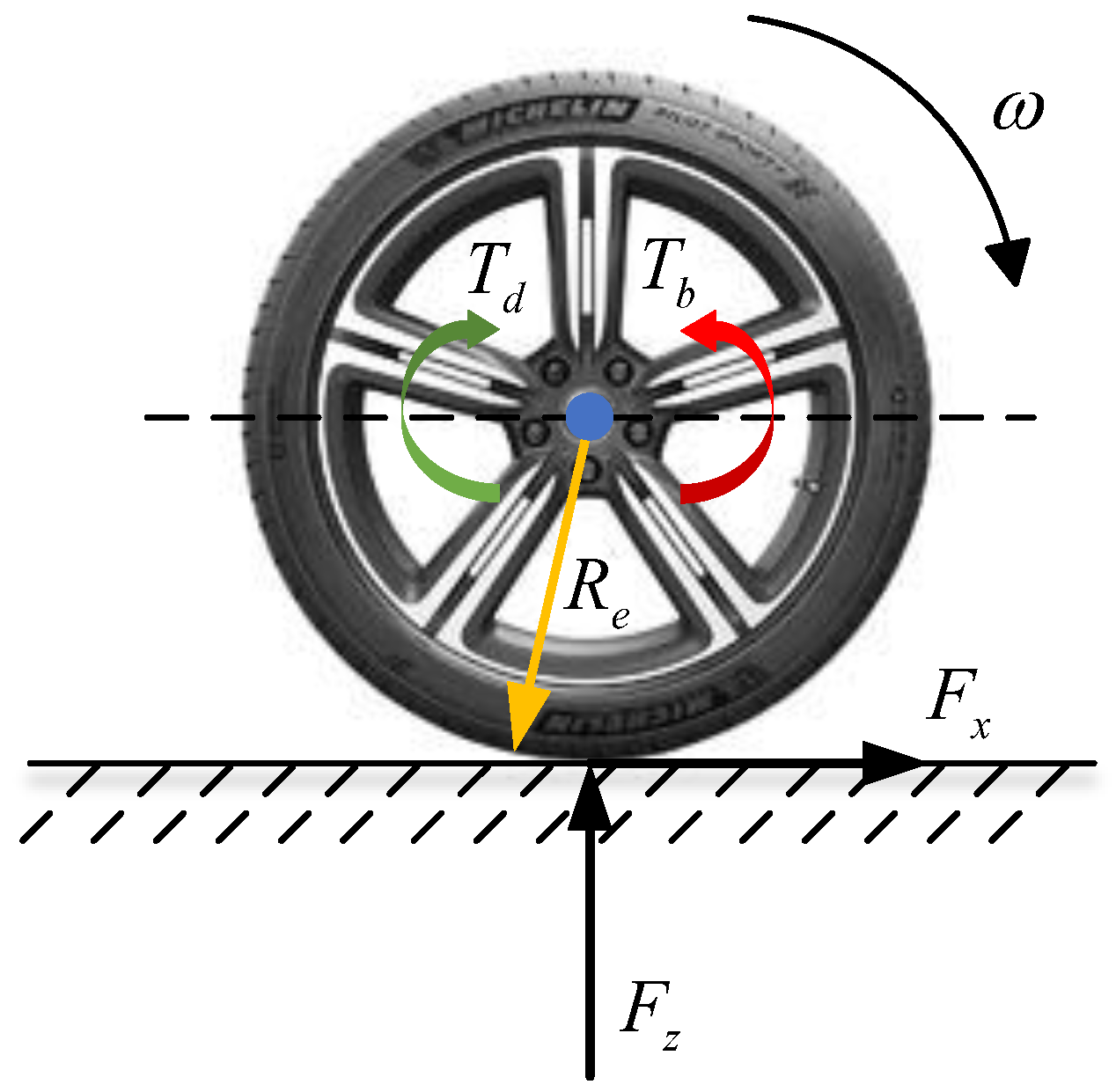

2.2. Wheel Rotational Dynamics Model

2.3. Tire Model

2.4. Hub Motor Model

2.5. Driver Model

3. The Design of the Estimator for Sideslip Angle Estimation

3.1. RUPF-Based Sideslip Angle Estimation

- (1)

- Initialization: sample N particles with same weights 1/N generated by the prior PDF p(x0):

- (2)

- Calculate the importance density using UKF:

- (3)

- Importance sampling, sampling particles:where N(·) is a Gaussian function.

- (4)

- Update particle weights and normalize:

- (5)

- Systematic random resampling:

- ①

- Initialization of the cumulative distribution function (CDF): c0 = 0;

- ②

- Assign the CDF;

- ③

- For N particles, generate random numbers separately:

- (6)

- State the estimation output at the moment k.

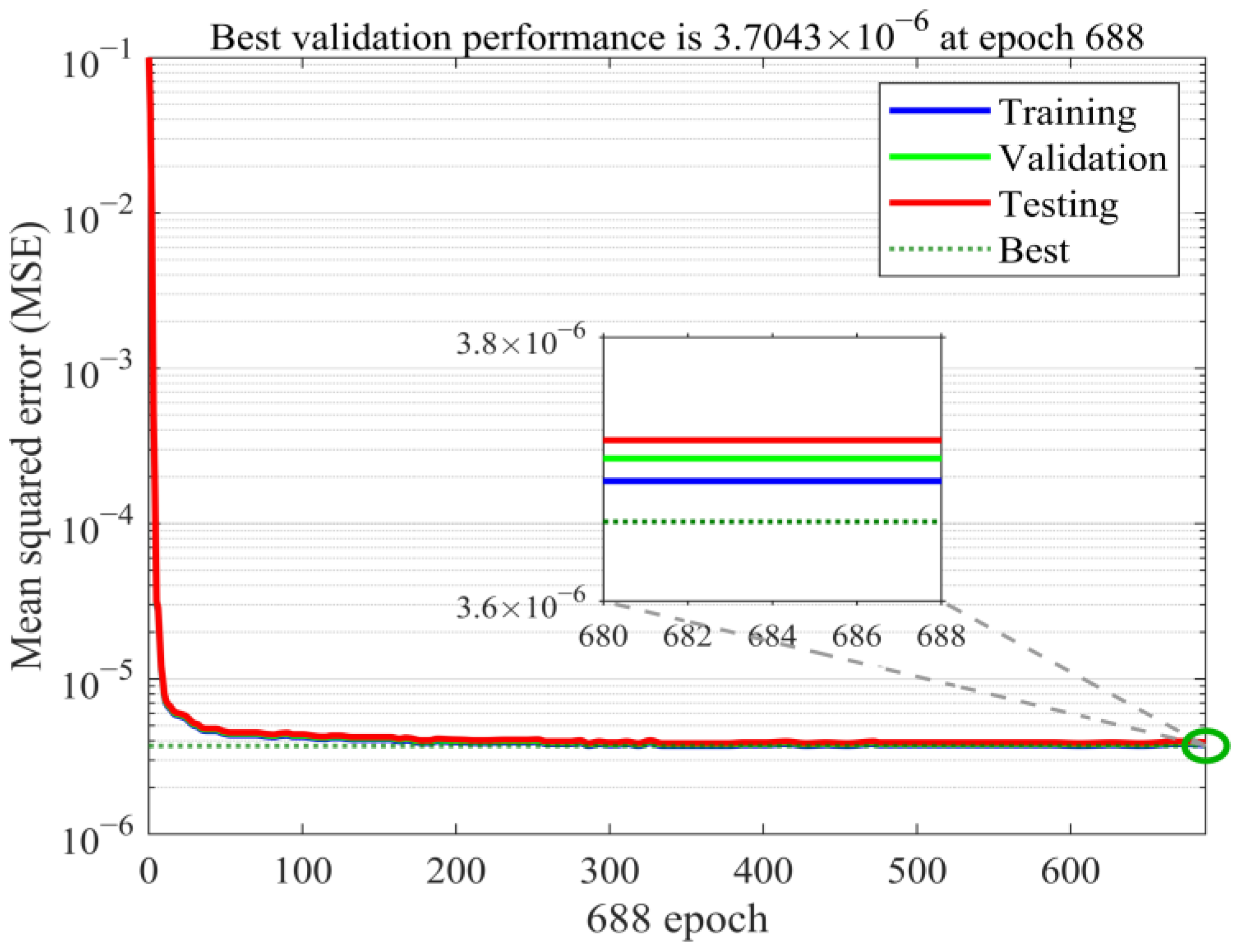

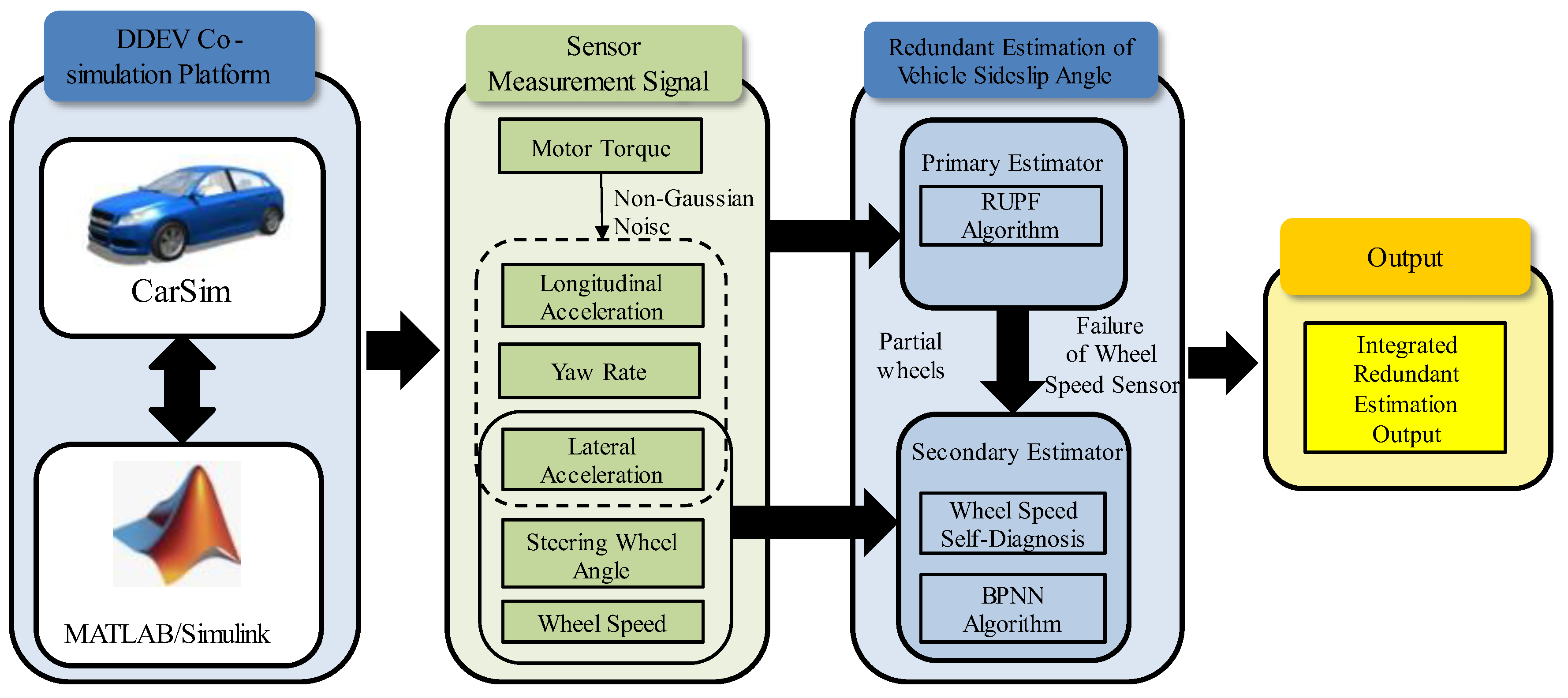

3.2. Neural Network Algorithm

3.2.1. Dataset Acquisition

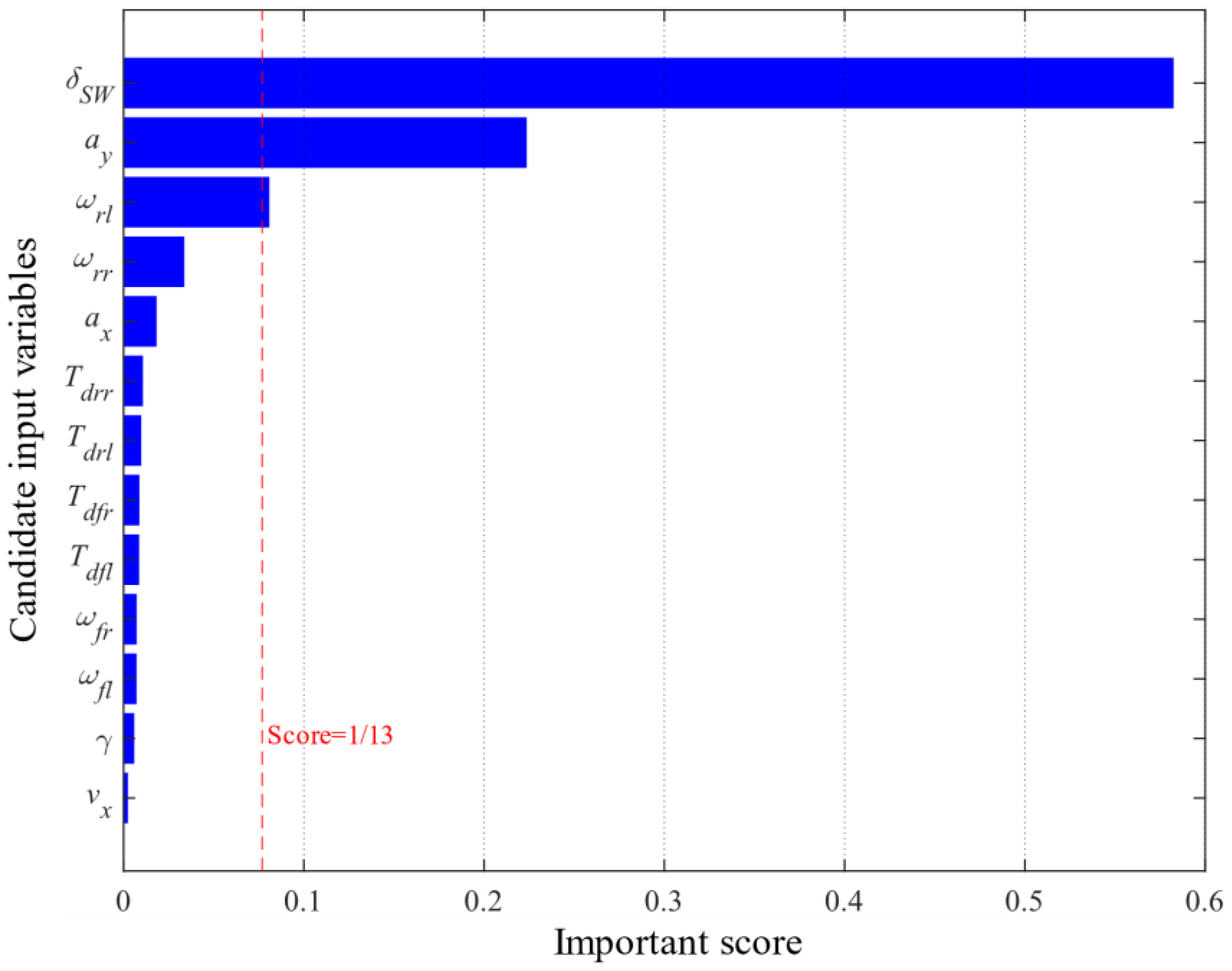

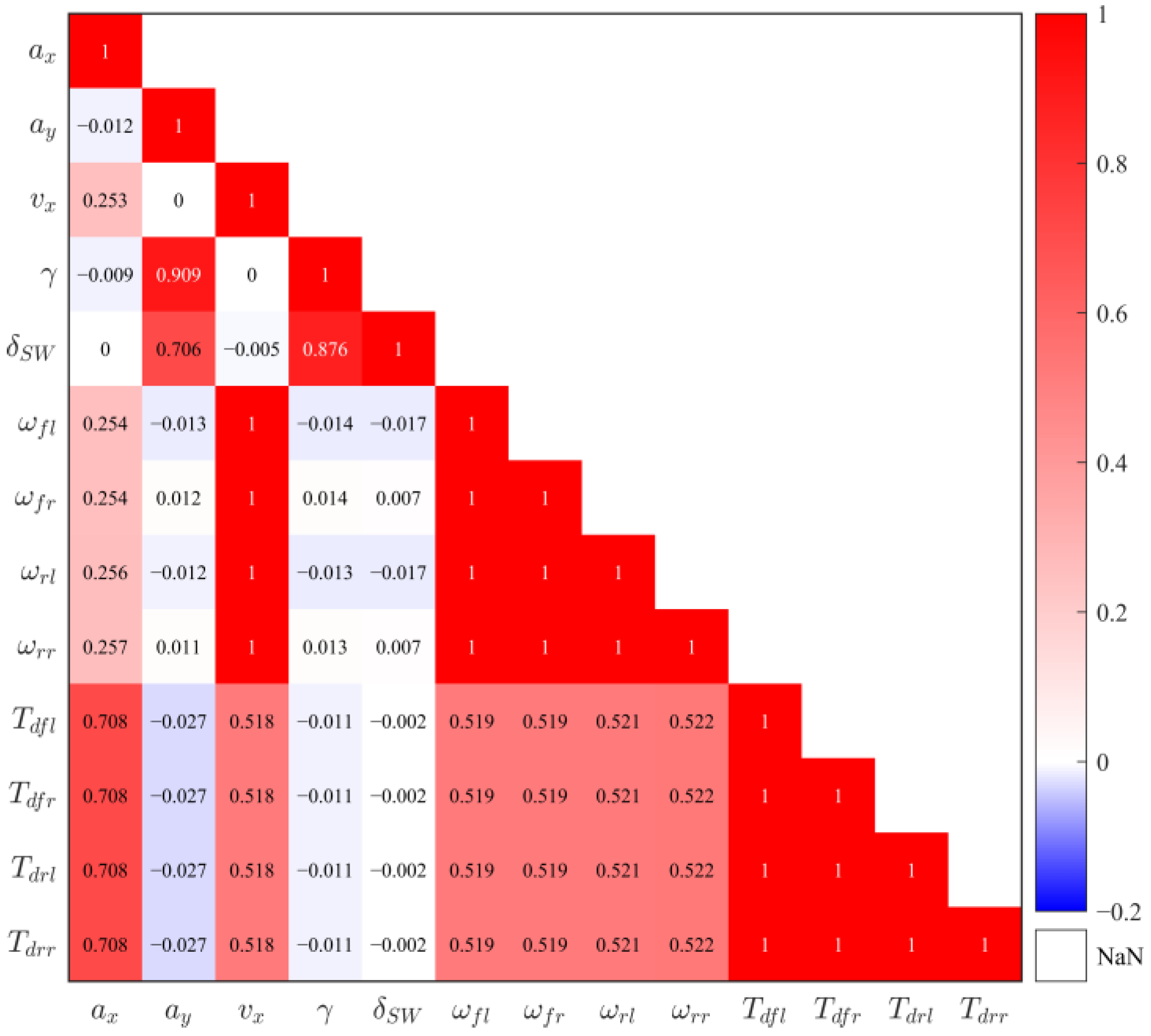

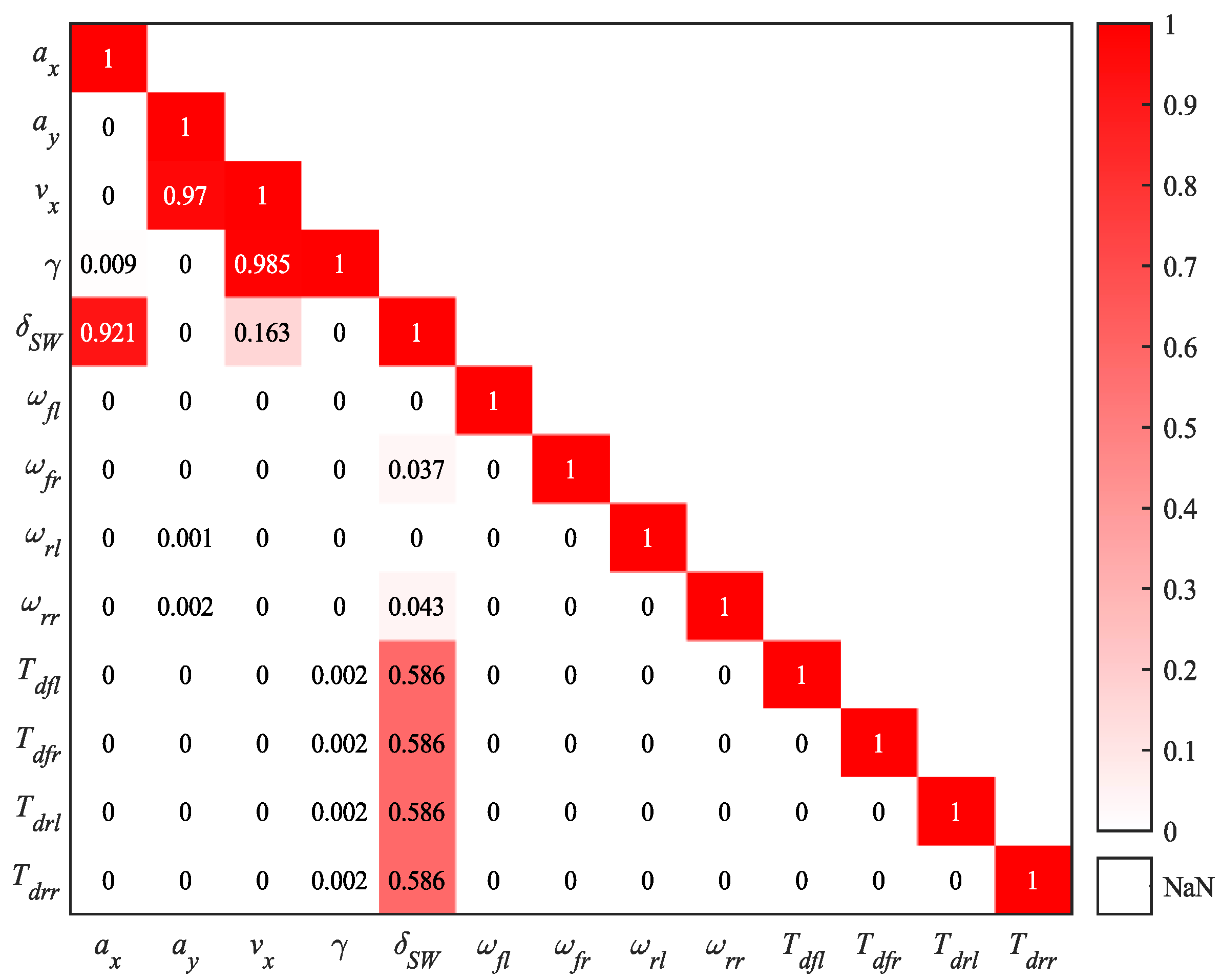

3.2.2. RF Feature Importance Analysis

3.3. Redundant Estimation Scheme Design

3.3.1. PCC Analysis

- (1)

- Correlation assessment: Calculate the correlation coefficient between each pair of variables:where NP represents the number of samples; X and Y are two variables; and are their means.

- (2)

- Significance judgment involves calculating the t-statistic between each pair of variables and then determining the significance p-value by consulting the t-distribution table. The t-statistic calculation equation is as follows:

3.3.2. Redundant Estimation Scheme

4. Simulation Verification

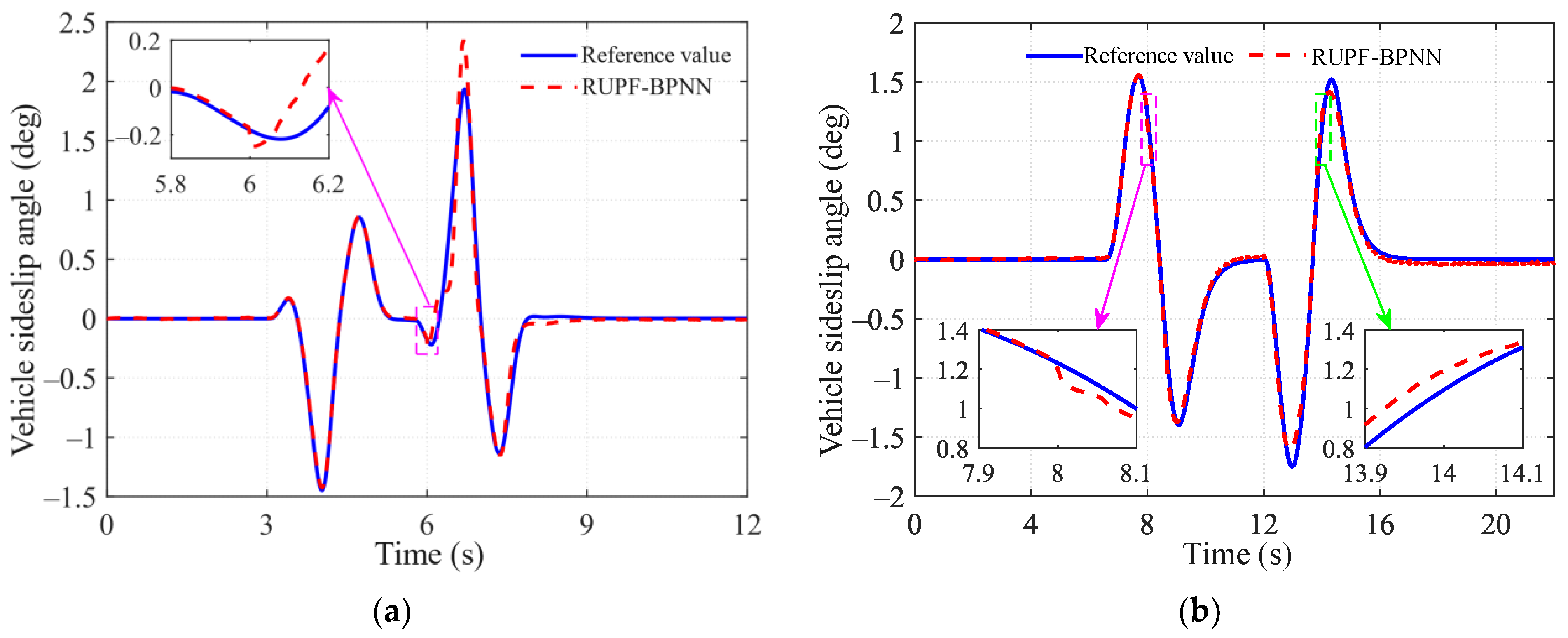

4.1. DLC Tests

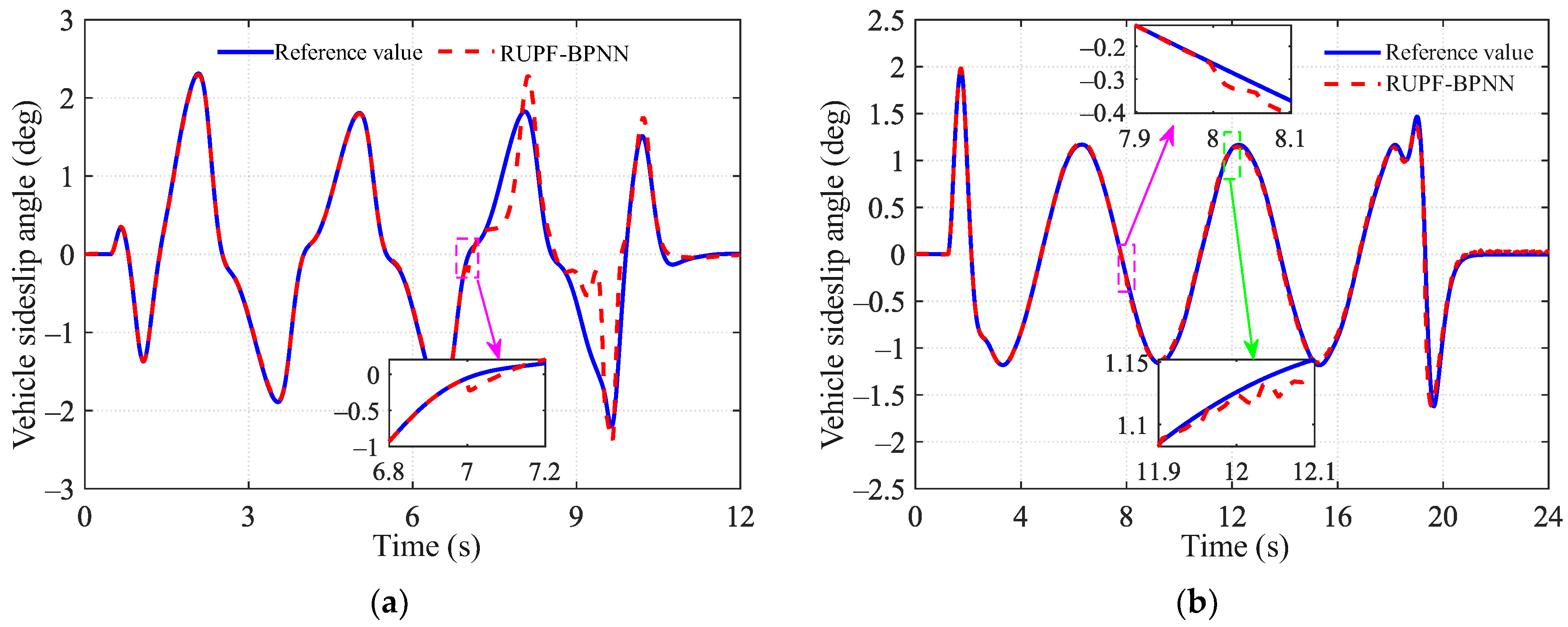

4.2. Slalom Tests

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrell, J.A.; Roysdon, P.F. Advanced Vehicle State Estimation: A Tutorial and Comparative Study. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 15971–15976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Driving Stability Control of Four-Wheel Independent Steering Distributed Drive Electric Vehicle with Single Wheel Steering Failure. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 60, 507–522. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Walker, P. Sideslip Angle Estimation of Ground Vehicles: A Comparative Study. IET Control Theory Appl. 2020, 14, 3490–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindamo, D.; Lenzo, B.; Gadola, M. On the Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation: A Literature Review of Methods, Models, and Innovations. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Gao, Y.; Fu, C.; Gostar, A.K.; Hoseinnezhad, R.; Hu, M. Vehicle State Estimation Based on Adaptive State Transition Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), Hangzhou, China, 18–20 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Jia, G.; Ran, X.; Song, J.; Wu, K. A Variable Structure Extended Kalman Filter for Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation on a Low Friction Road. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2014, 52, 280–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevly, D.; Ryu, J.; Gerdes, J. Integrating INS Sensors with GPS Measurements for Continuous Estimation of Vehicle Sideslip, Roll, and Tire Cornering Stiffness. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2006, 7, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, Y.; Guo, K. A Reduced-Order Nonlinear Sliding Mode Observer for Vehicle Slip Angle and Tire Forces. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2014, 52, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, L.; Cai, Y.; Xu, X. Robust Sideslip Angle Observer with Regional Stability Constraint for an Uncertain Singular Intelligent Vehicle System. IET Control Theory Appl. 2018, 12, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, F.; Sabbioni, E.; Pesce, M.; Melzi, S. A Methodology for Vehicle Sideslip Angle Identification: Comparison with Experimental Data. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2007, 45, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pang, H.; Xu, Z.; Jin, J. On Co-Estimation and Validation of Vehicle Driving States by a UKF-Based Approach. Mech. Sci. 2021, 12, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Chen, J.; Zou, J. Vehicle State Estimation Using Cubature Kalman Filter. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 17th International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Chengdu, China, 19–21 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chindamo, D.; Gadola, M. Estimation of Vehicle Side-Slip Angle Using an Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Mechanical, Aeronautical and Automotive Engineering (ICMAA 2018), Singapore, 24–26 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Wen, W.; Tang, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G. Estimation of Vehicle Motion State Based on Hybrid Neural Network. Automot. Eng. 2022, 44, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Gräber, T.; Lupberger, S.; Unterreiner, M.; Schramm, D. A Hybrid Approach to Side-Slip Angle Estimation with Recurrent Neural Networks and Kinematic Vehicle Models. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2019, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, F.; Liu, C. Vehicle State Estimation Based on Extended Kalman Filter and Radial Basis Function Neural Networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Tonoli, A.; Amati, N. A deep learning based virtual sensor for vehicle sideslip angle estimation: Experimental results. In Proceedings of the WCX World Congress Experience, Detroit, MI, USA, 10–12 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Novi, T.; Capitani, R.; Annicchiarico, C. An Integrated Artificial Neural Network–Unscented Kalman Filter Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Based on Inertial Measurement Unit Measurements. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2019, 233, 1864–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Min, K.; Kim, H.; Huh, K. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Ensemble-Based Adaptive Kalman Filter. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 144, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; He, D.; Mo, S. A Hybrid Physics–Data Driven Approach for Vehicle Dynamics State Estimation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 225, 112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Y.; Lu, B.; Xing, S.; Zong, C. Reinforcement learning-based fusion framework for vehicle sideslip angle estimators using physically guided neural networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 238, 113211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, G.; Pacejka, H.; Lidner, L. A New Tire Model with an Application in Vehicle Dynamics Studies; SAE Technical Paper 890087; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Cheng, Q.; Victorino, A.; Charara, A. Nonlinear observers of tire forces and sideslip angle estimation applied to road safety: Simulation and experimental validation. In Proceedings of the 2012 15th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Anchorage, AK, USA, 16–19 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sbarufatti, C.; Cadini, F. Multiple Local Particle Filter for High-Dimensional System Identification. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 209, 111060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuptametee, C.; Michalopoulou, Z.; Aunsri, N. A Review of Efficient Applications of Genetic Algorithms to Improve Particle Filtering Optimization Problems. Measurement 2024, 224, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Rong, F.; Zhang, P.; Yan, F. Sideslip Angle Estimation for Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Based on Robust Unscented Particle Filter. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3888-2:2018; Passenger Cars—Test Track For A Severe Lane-Change Manoeuvre—Part 1: Double Lane-Change. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 15037-1:2019; Road Vehicles—Vehicle Dynamics Test Methods—Part 1: General Conditions for Passenger Cars. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

| Parameter | Peak Torque | Rated Torque | Rated Power | Maximum Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1250 N·m | 650 N·m | 54 kW | 1600 r/min |

| Collection Conditions | Road Adhesion | Speed Range (km/h) |

|---|---|---|

| DLC | 0.3 | 20–60 |

| DLC | 0.5 | 20–70 |

| DLC | 0.85 | 20–130 |

| Slalom | 0.3 | 20–40 |

| Slalom | 0.5 | 20–60 |

| Slalom | 0.85 | 20–70 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Vehicle mass m/kg | 1501 |

| Distance from the vehicle’s center of gravity to front axle a/m | 1.015 |

| Distance from the vehicle’s center of gravity to rear axle b/m | 1.895 |

| Height of the center of gravity hg/m | 0.54 |

| Front track width df/m | 1.675 |

| Rear track width dr/m | 1.675 |

| Yaw moment of inertia Iz/(kg·m2) | 1536.7 |

| Effective tire radius R/m | 0.325 |

| Wheel moment of inertia J/(kg·m2) | 1.5 |

| Performance Metrics | DLC | |

|---|---|---|

| μ = 0.7 | μ = 0.4 | |

| MaxAE | 0.5295 | 0.1855 |

| MAE | 0.0340 | 0.0332 |

| RMSE | 0.0816 | 0.0466 |

| Performance Metrics | Slalom | |

|---|---|---|

| μ = 0.7 | μ = 0.4 | |

| MaxAE | 1.2833 | 0.5551 |

| MAE | 0.1037 | 0.0286 |

| RMSE | 0.2408 | 0.0539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, D.; Hu, J.; Sun, G.; Rong, F.; Zhang, P.; Huang, Y.; Cao, Z. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Redundant Estimation Based on Multi-Source Sensor Information Fusion. Mathematics 2026, 14, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010183

Chen D, Hu J, Sun G, Rong F, Zhang P, Huang Y, Cao Z. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Redundant Estimation Based on Multi-Source Sensor Information Fusion. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Danhua, Jie Hu, Guoqing Sun, Feiyue Rong, Pei Zhang, Yuanyi Huang, and Ze Cao. 2026. "Vehicle Sideslip Angle Redundant Estimation Based on Multi-Source Sensor Information Fusion" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010183

APA StyleChen, D., Hu, J., Sun, G., Rong, F., Zhang, P., Huang, Y., & Cao, Z. (2026). Vehicle Sideslip Angle Redundant Estimation Based on Multi-Source Sensor Information Fusion. Mathematics, 14(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010183