1. Introduction

The need to mitigate climate change is driving a global transition towards renewable energy sources to replace electricity generation methods based on fossil fuel combustion. Such conventional techniques contribute significantly to anthropogenic climate change through the emission of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) (including carbon dioxide

CO2, methane gas

CH4, nitrous oxide

N2O, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs) and sulfur hexafluoride

SF4) which absorb and emit infrared radiation, thus intensifying the planetary greenhouse effect and increasing the carbon footprint. Each kilowatt-hour generated by these means is estimated to produce approximately 181 g of

CO2 [

1].

PV systems represent an important alternative that uses solar irradiance, which is an inexhaustible energy source, for conversion into electrical power via semiconductor materials such as silicon. This clean technology is essential to satisfy energy demands while enhancing comfort conditions. Nevertheless, solar power generation is inherently intermittent, subject to variability from extrinsic factors (e.g., geographic location, season, and weather) and intrinsic factors (e.g., cell technology, orientation, and system losses) [

2].

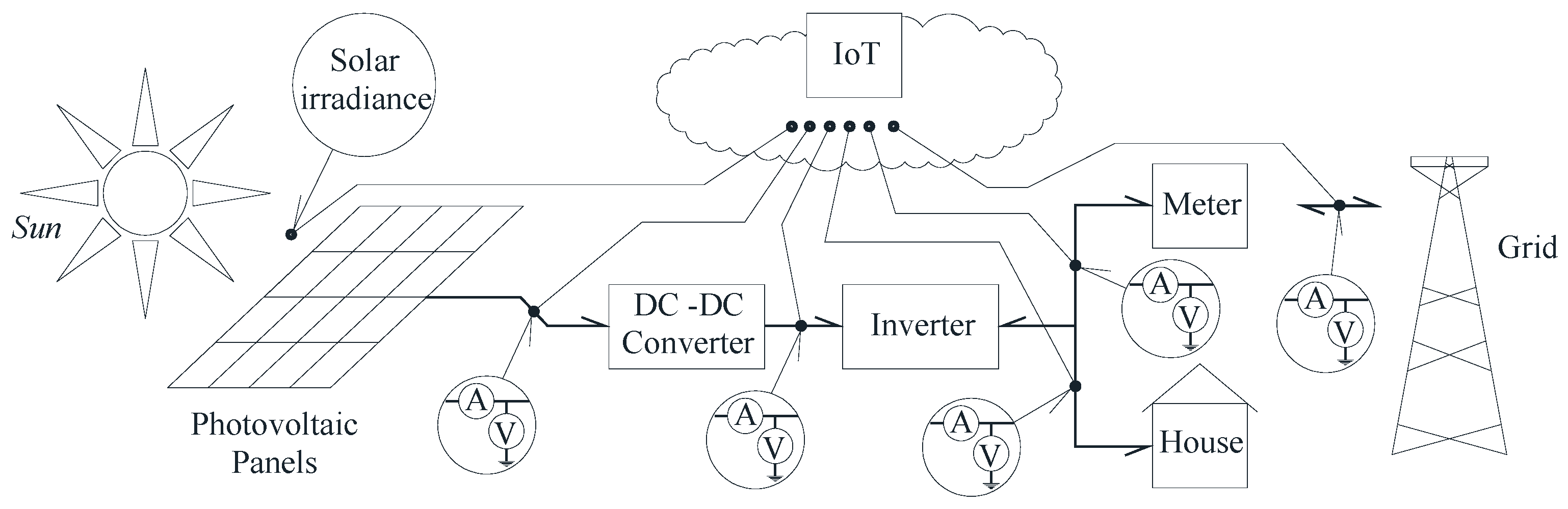

To ensure the efficiency and stability of PV systems, the monitoring of critical electrical parameters within energy collection and distribution networks via Internet of Things (IoT) technology is important. Contemporary scholarly investigations have propelled significant advances in IoT, yielding paradigms such as the Social IoT (SIoT) for resource optimization [

3] and Integrated Sensing and Communications (ISAC) for enhanced module efficiency [

4]. The deployment of low-power wide-area networks (LPWAN, NB-IoT) provides the essential communication infrastructure [

5], with demonstrable efficacy in applications ranging from biomedical monitoring [

6] to secure decentralized data authentication [

7].

However, a principal complication is that measurements acquired from IoT monitoring systems are frequently corrupted by noise from the aforementioned factors, thereby hiding the true behavior of the system and limiting precise characterization. Conventional filtering techniques, including moving average filters, Fourier-based transforms (FFT), and finite/infinite impulse response (FIR/IIR) filters, often prove inadequate. Their limitations manifest either in a failure to address the probabilistic nature of the noise and system parameters optimally or due to excessive computational complexity for implementation on resource-constrained embedded systems.

Signal reconstruction is formally defined as the procedure of generating a continuous signal from a discrete collection of samples, which constitutes a pillar of signal processing. This methodology enables the retrieval of original waveforms and the preservation of informational integrity. The fidelity of reconstruction is critically dependent on both the sampling frequency and the algorithmic methodology used, with prevalent techniques encompassing-sinc and polynomial interpolation, each possessing distinct advantages and constraints [

8,

9]. The process typically involves interpolation and filtering, in which a low-pass filter is frequently indispensable for the elimination of high-frequency noise and the mitigation of aliasing—a deleterious effect where signals become irrecoverably superimposed due to inadequate sampling [

8].

A foundational theoretical precept in this discipline is the Shannon–Nyquist sampling theorem, widely used for the reconstruction of stochastic processes. Although extensively used, this classical theorem demands rigorous prerequisites: an unbounded number of samples, a spectrally band-limited signal, periodic sampling instants, and strict compliance with the Nyquist criterion. A significant theoretical flaw is its failure to delineate applicability to deterministic or random processes, nor does it stipulate the required probability density function of the underlying process [

9,

10].

In response to these constraints, more sophisticated methodologies have been formulated. Ref. [

10] advanced the application of the conditional expectation rule for the reconstruction of Gaussian processes. This system proffers substantial benefits, notably its capacity to accommodate both band-limited and non-band-limited spectra, periodic and aperiodic sampling regimes, and finite or infinite sample sizes. Moreover, it formulates the reconstruction on the statistical properties of the process and yields explicit expressions for both the reconstruction and error functions. The research documented by [

10] further incorporates a comparative analysis of RC and Chebyshev filter configurations, thereby facilitating the identification of an optimal design by analyzing the variance of the reconstruction error variance.

An alternative technique is the Wavelet Transform, employed by [

11] for the reconstruction of sinusoidal signals. This approach provides a contrast to conventional Fourier analysis and is interpreted through its continuous and discrete formulations. Reference [

11] delineates the decomposition of a sinusoidal signal into scaling and wavelet coefficients, using the Haar mother wavelet as the foundational basis function. The practical efficacy of such techniques is further evidenced by their deployment in real-world applications; for example, ref. [

12] implemented a statistical signal reconstruction system, integrated with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Butterworth filters, for the analysis of phonocardiograms in cardiac medicine, demonstrating a marked improvement in signal clarity.

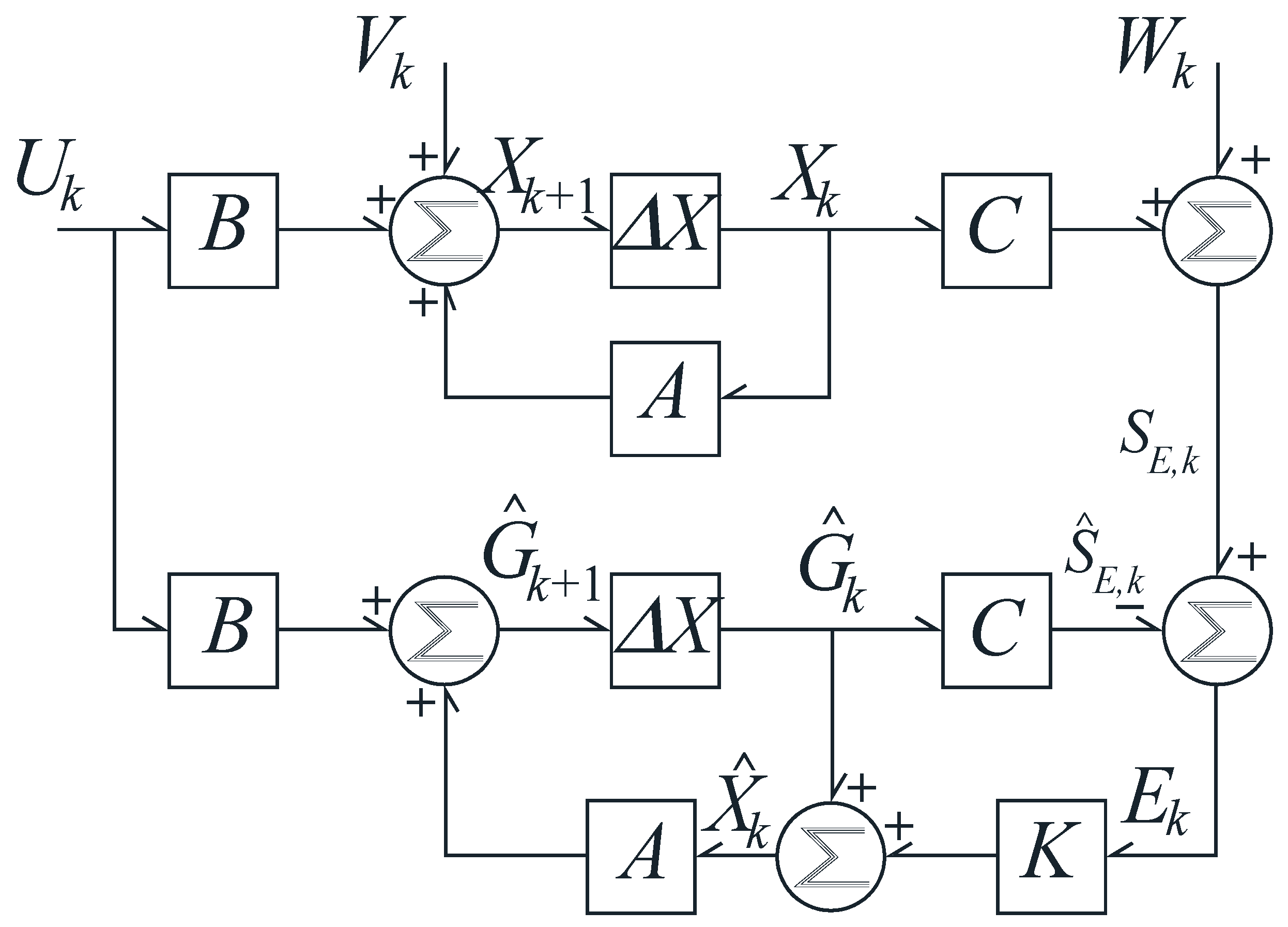

A superior alternative to the mathematical design complexity of classical filters and the limited operating range of simple averages is the KF. Conceived by Rudolf Kalman in 1960 [

13] as a recursive algorithm for linear quadratic estimation, its operation is delineated in a recursive predict-correct cycle (see

Figure 1), which leverages the Kalman Gain to optimally weight new measurements against prior state estimates.

This statistical foundation affords it a natural proficiency in eliminating Gaussian noise and a close conceptual relationship with Gaussian filters (governed by Equations (1) and (2)), though with superior adaptability for dynamic systems.

In Equation (1) (t) is the distribution function, σ is the standard deviation, σ2 is the variance, µ is the statistical mean of the sampled data of a signal, t is the time considered for the filtered signal window and u is the integration variable.

On the other hand, the normal distribution function, when solved as a function of time, generates the density function shown in Equation (2). The density function describes the main equation of a Gaussian filter.

A survey of the literature reveals a tool of remarkable breadth, fulfilling three distinct yet interconnected roles: (a) As a sophisticated filter: The KF excels as a noise filter for sensor data. Ref. [

14] detailed its design and real-time implementation for inertial measurement unit (IMU) signal denoising. (b) As an identifier (state estimator): The KF infers latent system states. Ref. [

15] further applied it to identify and correct a vehicle’s true position from unreliable GPS data [

16]. (c) As a reconstructor: The KF serves as a powerful tool for signal reconstruction from noisy datasets. Ref. [

17] employed a dual-KF configuration to reconstruct valid signals from profoundly noisy climatological measurements.

Nevertheless, despite its established efficacy in filtering and state estimation, the direct application of the standard KF to the reconstruction of PV power trajectories encounters specific challenges stemming from the operational nature of such systems. These include the presence of non-Gaussian and intermittent measurement noise, arising from inverter switching, partial shading, temperature and humidity variations, and rapid irradiance fluctuations. As well as the requirement for lightweight, adaptive algorithms capable of efficient execution on resource-constrained embedded devices typical of IoT monitoring networks. The conventional KF, which assumes stationary Gaussian noise and employs fixed covariance matrices, is not designed to handle these dynamics optimally.

To address these limitations, this work proposes an adaptive KF system specifically designed for PV trajectory reconstruction. The proposed approach incorporates an adaptive noise model that enables the online identification of the system’s input and output covariances, thereby adapting to the intermittent noise characteristic of PV environments. Furthermore, it adds the capability to reconstruct the complete power trajectory for diagnostic purposes, facilitating the detection of faults or performance degradation. Finally, it integrates simultaneous system parameter identification and noise filtering, which enhances the model while cleaning the signal.

The central hypothesis is that by explicitly addressing these PV-specific challenges, reconstruction fidelity can be significantly improved relative to what is achievable with a conventional KF application. Consequently, the main objective of this manuscript is to demonstrate the relevance and effectiveness of this adaptive KF approach for the accurate reconstruction of electrical parameter behavior in solar energy-collection networks, using data obtained from solar farms via IoT monitoring systems.

This study aims to design and validate an adaptive Kalman filtering system for reconstructing PV power trajectories in IoT-based monitoring systems. To this end, it is proposed, first, to develop an adaptive noise covariance estimation mechanism, tailored to the intermittent noise of PV systems. Second, the system will be implemented on a resource-constrained IoT edge-cloud architecture. Subsequently, the fidelity of the reconstruction will be quantitatively validated using statistical metrics (MSE, probability moments, PDFs). Finally, the diagnostic potential of the reconstructed trajectories for fault detection will be evaluated.

To implement this strategy, the KF is used as a reconstructor of power trajectories. Its performance will be validated using real-world data acquired from a proprietary IoT monitoring system, architected upon a two-layer paradigm: (a) an Edge Layer for real-time electrical parameter acquisition and processing, and (b) a Cloud Layer for platform integration, visualization, and analysis. The validation will entail a quantitative comparison with directly measured signals, employing descriptive measures such as the first and second-order probability moments, the probability distribution function, and the mean square error.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 delineates the electrical parameters in energy harvesting networks;

Section 3 presents the architectural design and implementation of the IoT photovoltaic monitoring platform and the results of the electrical parameter reconstruction using the Kalman Filter;

Section 4 engages in a discussion of the investigation’s findings; and finally,

Section 5 shows the concluding remarks.

3. Results

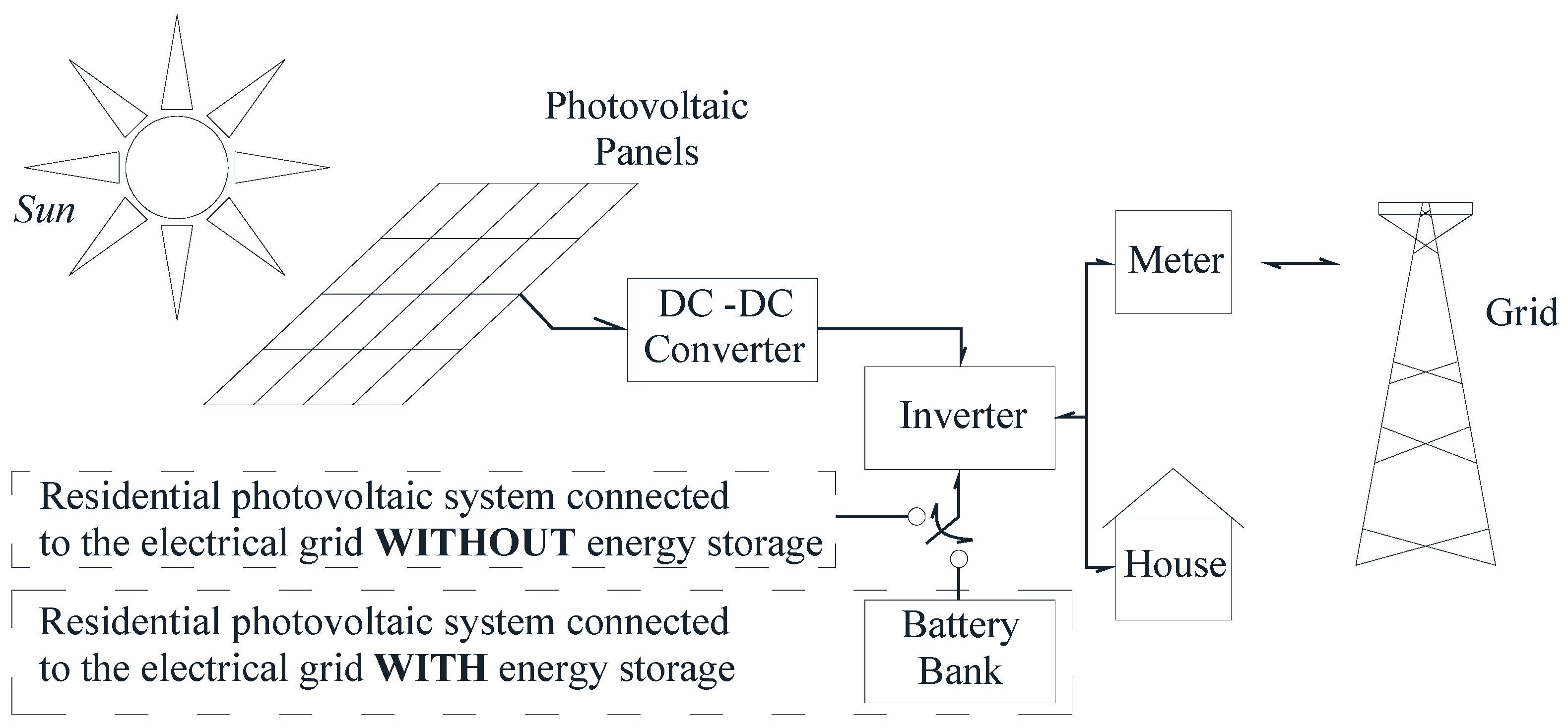

3.1. Architectural Design and Implementation of an IoT Photovoltaic Monitoring Platform

The integration of renewable energy in Mexico represents a strategic challenge that demands national technological innovation [

27]. In this context, the Universidad Tecnologica Emiliano Zapata del Estado de Morelos (UTEZ), in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional de Electricidad y Energias Limpias (INEEL) of Mexico, developed an electrical parameter measurement system to evaluate and validate the first Mexican-made photovoltaic inverter [

28].

Detailed technical information about the PV inverter is not disclosed in this work because the device is currently in an active development phase and undergoing a patent application process. For confidentiality and intellectual property protection reasons, only general operational characteristics and measurement results are presented, without revealing specific design details, control strategies, or proprietary hardware and firmware implementations.

This monitoring device was designed to record, in real-time, critical variables such as voltage, current, power, energy, frequency, and power factor, both in PV systems and conventional three-phase installations.

A comprehensive IoT platform was developed to address this, using a layered architecture that integrates physical sensing with cloud analytics. This ensures robust data acquisition, reliable transmission, and accessible visualization for complete PV performance assessment. The system’s two core layers are the edge infrastructure (for physical interaction and initial data handling) and the cloud integration (for storage, processing, and visualization). The following subsections detail each layer’s components.

As reported in previous studies, conventional electrical monitoring, which is typically based on local measurement devices, power analyzers or supervisory equipment, can provide very high metrological accuracy, but it usually depends on local access, manual data retrieval or wired installations, which restricts scalability and make continuous observation of the electrical parameters more inefficient [

29]. In other words, while traditional systems are very robust from the measurement point of view, they are less practical when longterm monitoring, multiple measurement nodes or remote access are required, especially in experimental photovoltaic scenarios.

Conversely, several recent works have highlighted that IoT platforms enable real-time access to data, remote visualization and cloud-based historical storage, making it easier to compare operational conditions and identify abnormal behavior without the need to be physically present at the installation [

30]. These capabilities are particularly useful in distributed photovoltaic systems, where researchers frequently need to evaluate configuration changes, inverter performance or load variations over extended periods.

Nevertheless, the limitations of IoT solutions are also recognized in the literature, including dependence on network availability, potential cybersecurity concerns and the need for periodic calibration of low-cost sensors. In this case, these aspects were explicitly considered by using a stable institutional Wi-Fi network and by validating the measurements against a certified power-quality analyzer (ABB CMS-700, ABB Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland).

3.1.1. Edge Layer: Data Acquisition and Processing

The client, also referred to as the Edge Layer (see

Figure 8), of the IoT monitoring system employs PZEM-004T-100A acquisition modules (Peacefair Electronic Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) and an ESP8266 wireless communication interface (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China) [

31,

32], transmitting data to the IoT platform ThingsBoard [

33], which enables remote visualization and analysis of the inverter’s electrical behavior. The inverter circuit cannot be disclosed because it is protected by intellectual property rights authorized by the Mexican government, with INEEL owning this intellectual property and patent.

The PZEM-004T-100A module is a compact sensor for measuring electrical parameters in single-phase AC systems, including voltage (Vrms), current (Irms), active power, energy, frequency, and power factor. It operates typically from 80 to 260 Vrms and up to 100 Arms using an external clip-on current transformer that provides galvanic isolation and simplifies installation. According to the manufacturer, the sensitivity to load variations and a typical accuracy of 0.5–1% for voltage and current and around 1% for power and energy.

For validation, an ABB CMS-700 power quality analyzer (ABB Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland) was employed as a reference instrument. The CMS-700 provides high-accuracy measurements of voltage, current, power, energy, power factor, and harmonic components, and is intended for detailed analysis of electrical quality. The experimental comparison confirmed that, although the PZEM-004T-100A has lower metrological performance than the CMS-700, its deviations remain within acceptable limits for monitoring and energy management in low-voltage PV applications, supporting its use as an embedded, cost-effective sensing solution.

This work utilizes a Wi-Fi IoT architecture because the deployment site (Docencia 2 Building) has complete Wi-Fi coverage. This existing network allows for high-data-rate, real-time transmission without the need for additional LPWAN hardware or subscriptions. Although technologies like LoRaWAN are better suited for wide-area, low-power field deployments, the available Wi-Fi infrastructure provided a simpler, more cost-effective, and technically sufficient solution for this campus-based pilot study. Additionally, analytical tools based on WinPython 3.10.12.0 and Jupyter Notebook 6.5.4 were integrated to automatically generate statistical and graphical reports [

34].

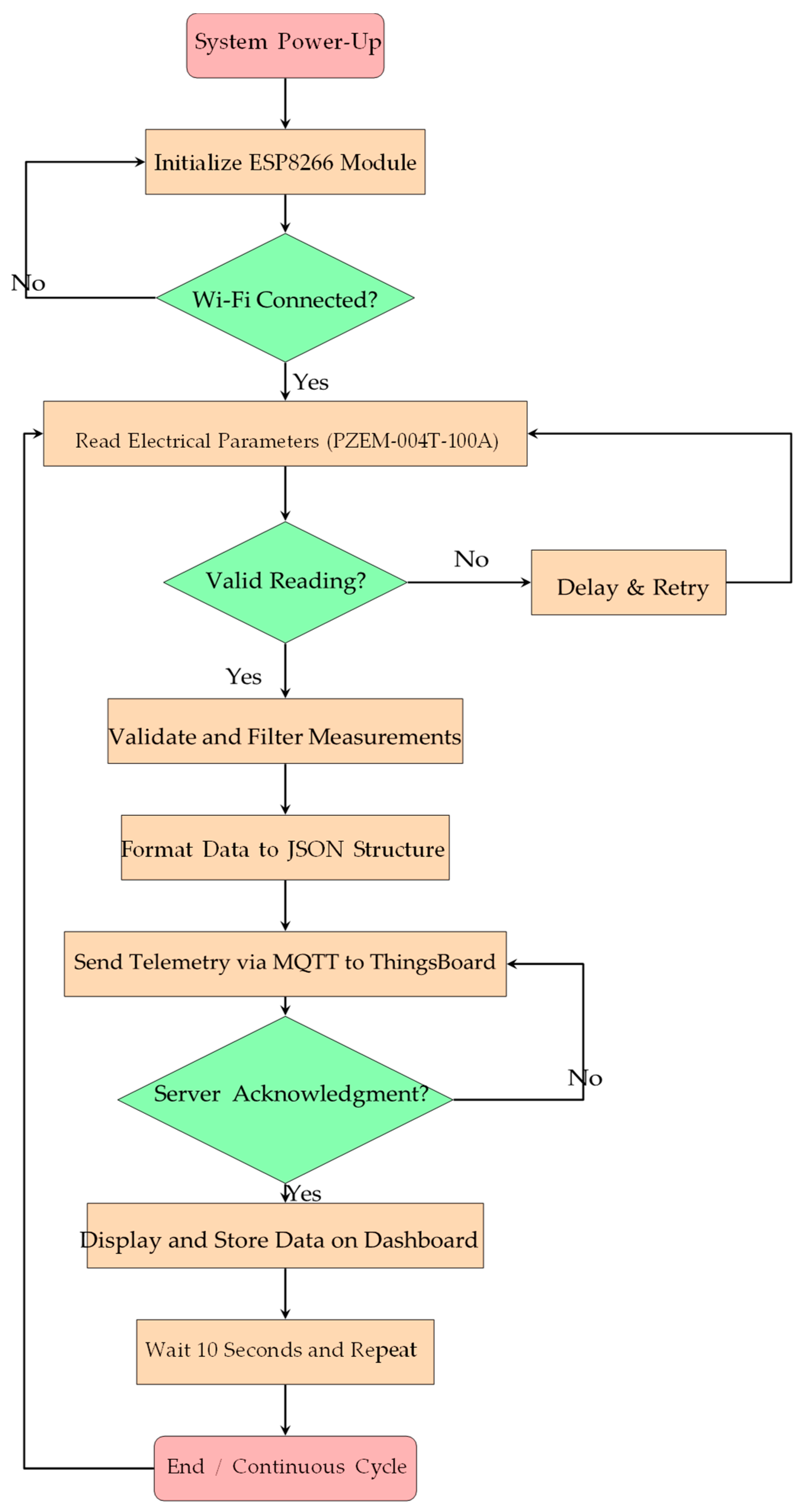

In

Figure 9, the flowchart of the measurement and data transmission process is presented. The diagram begins with the system power-up and the initialization of the ESP8266 module, which establishes a Wi-Fi connection to the local network.

Once the connection is successfully established, the microcontroller performs the acquisition of electrical parameters through the PZEM-004T-100A sensors, measuring instantaneous values of voltage, current, active power, accumulated energy, frequency, and power factor for each monitored line. It is important to emphasize that this flowchart exclusively describes the operational logic of the data acquisition and IoT communication system, including data validation and transmission to the monitoring platform, and does not represent any control, optimization, or decision-making process related to inverter operation or power trajectory improvement. The proposed workflow is therefore limited to monitoring and visualization functions, ensuring reliable and continuous data collection without influencing the photovoltaic system’s power generation behavior.

The acquired data are temporarily stored in internal variables and subjected to a validation and filtering routine to prevent errors due to unstable readings or sensor communication loss. Then, the ESP8266 formats the information into a JSON structure and sends the telemetry data to the ThingsBoard platform via the MQTT protocol [

35].

3.1.2. Cloud Layer: Platform Integration and Visualization

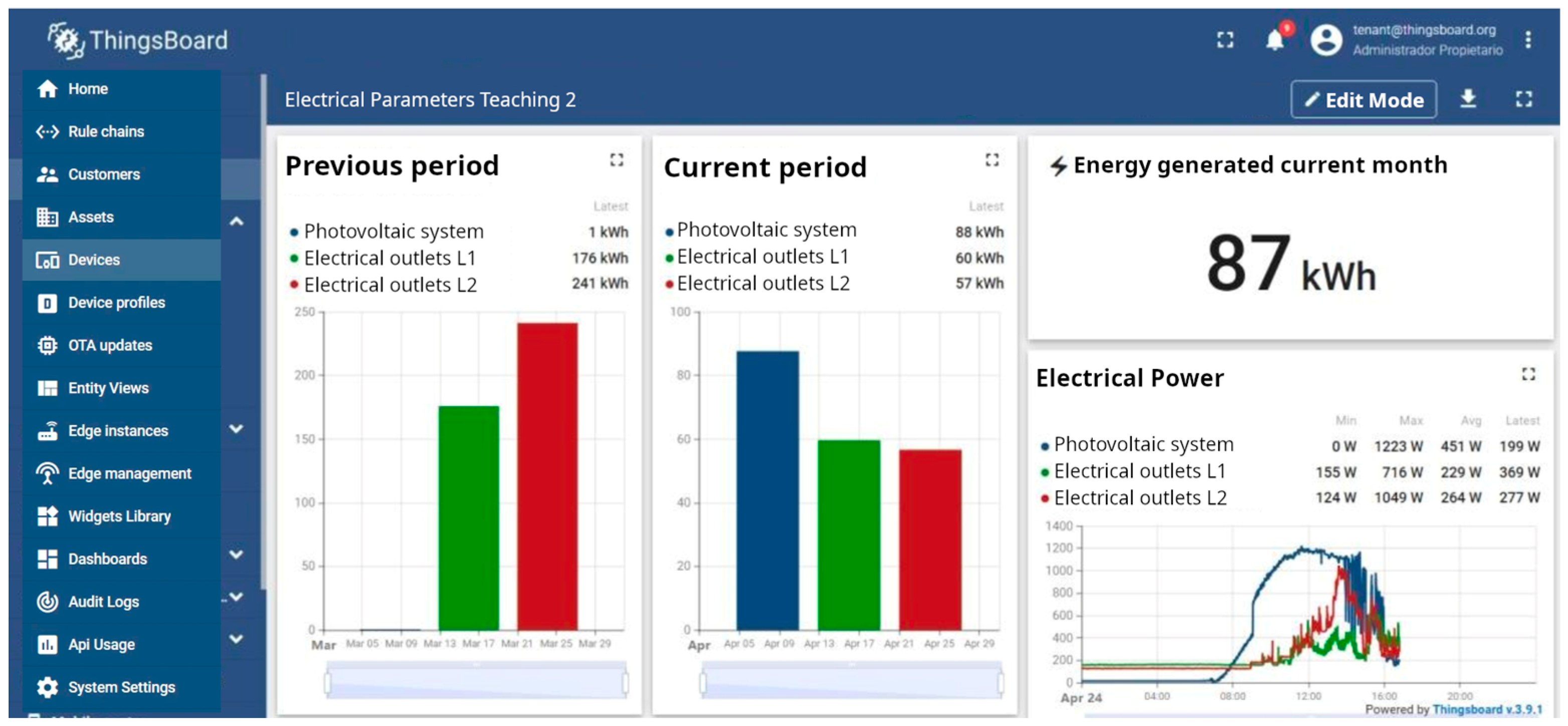

Once the central cloud platform (the server) acknowledges the data reception, the measurements are displayed in real-time through interactive dashboards configured in Things-Board, where electrical quantities are plotted, historical data are stored, and automatic alerts or reports can be generated. The process is repeated cyclically at defined intervals (approximately every 10 s), ensuring the continuous update of the operational status of the PV system or the monitored three-phase installation. The ThingsBoard dashboard (see

Figure 10) serves as the primary interface for real-time visualization and management of the electrical parameters measured by the monitoring device [

36]. It is a web-based graphical environment that enables users to observe, analyze, and interpret system performance through dynamic widgets and interactive charts. The dashboard is composed of multiple panels that display key electrical variables acquired by the PZEM-004T-100A sensors, including voltage (V), current (A), active power (W), energy consumption (kWh), frequency (Hz), and power factor (PF) for each of the three monitored phases.

These values are updated every 10 s, ensuring continuous and accurate data representation. Each variable is displayed using dedicated widgets such as line charts, gauge indicators, and numeric value cards, allowing the user to easily identify operational trends, instantaneous values, and deviations from expected ranges. The ThingsBoard IoT platform automatically stores all incoming telemetry data in a cloud-based database, enabling historical analysis and performance comparison over time. Additionally, the dashboard integrates status indicators that confirm the device’s connectivity and data transmission status. When a connection loss or abnormal reading occurs, the interface can trigger automated alerts or notifications via email or MQTT messages. Overall, the dashboard provides a comprehensive monitoring and diagnostic tool, combining intuitive visualization with robust backend data handling, facilitating both technical evaluation of the PV inverter and educational use in energy system analysis.

During implementation, the device proved to be a reliable tool for the characterization of the inverter, supporting early fault detection and efficiency validation under real operational conditions. This development not only promotes technological autonomy within the national photovoltaic sector but also enhances the academic training of students through the application of monitoring methodologies based on open-source hardware and software. The results obtained demonstrate the potential of this system as a strategic support for the consolidation of a domestic PV inverter industry.

3.2. Description of the Installed 4 kW PV Generation System and Its Monitoring Platform

The PV system installed at the Docencia 2 Building of the Universidad Tecnológica Emiliano Zapata (UTEZ) represents a significant milestone in the institution’s applied research and renewable energy initiatives (geographical coordinates 18°51′06.3″ N, 99°12′03.1″ W, location

Figure 11b). The building where the PV system is installed has a daily demand of approximately 910 kW, due to the consumption of lighting fixtures and electronic devices used by the occupants. This energy consumption was determined through a detailed survey of the installed loads and the electrical equipment currently in operation at the site. The system has a total installed capacity of 4 kW, composed of twelve PV panels from different manufacturers, allowing for experimental configurations and comparative performance analysis under identical environmental conditions (See

Figure 11a).

It integrates four 1 kW PV inverters, each equipped with distinct firmware to evaluate variations in AC power generation, conversion efficiency, and grid synchronization behavior (see

Figure 11c). All inverter outputs are routed through a dedicated distribution board that is interconnected to the national electrical grid (CFE), enabling real-time monitoring of energy injection and system performance. This configuration not only provides a versatile platform for experimental and educational purposes but also contributes to the development of national expertise in PV system integration, control, and optimization for distributed generation in Mexico.

About the IoT-Based Photovoltaic System Monitoring, it maintained stable communication with a data refresh rate of approximately 10 s, ensuring minimal packet loss and reliable data integrity. The use of interactive widgets (like line charts, gauges, and digital indicators), enhanced the capacity for detecting transient events and analyzing long-term performance trends. Additionally, the system’s alert configuration enabled automatic notifications in case of communication loss or abnormal readings, improving reliability and response time.

Also, a robust and scalable environment for Internet of Things applications is provided, effectively bridging the gap between data acquisition at the device level and high-level data analytics. Its open-source nature and flexibility make it particularly suitable for research and educational contexts focused on renewable energy monitoring and smart grid systems.

Figure 12 shows power output record of the PV system, monitored by the electrical parameter measurement system and visualized through the ThingsBoard platform. The data correspond to the monitoring period from 22 to 23 July 2025, covering 48 h of continuous measurement with a sampling interval of 10 s.

Figure 12 shows electrical power monitoring of the PV system and derived circuits at the Docencia 2 of UTEZ. The electrical parameter monitoring system measures both the power generated by the photovoltaic array and the consumption of two branch circuits connected to the same distribution board. The blue points represent the generated power, while the red and orange points correspond to the power consumption of the two monitored circuits, respectively. This configuration demonstrates the dual measurement capability of the system, enabling simultaneous assessment of energy generation and consumption.

Looking at

Figure 12, we can see and approximate that the power delivered by the PV system is symmetrical throughout the days. With this consideration, the power delivered can be modeled as a half-period sinusoidal signal with a peak of 1600 W. To calculate the energy delivered in a day, the average sinusoidal power function is integrated with the time reference in hours. This calculation results in a daily energy output of 12.2 KWh.

In Mexico, the electricity consumption rate for a public university such as UTEZ is called “Gran Demanda en Media Tensión” (High Demand at Medium Voltage). Under this rate, costs vary according to the season, consumption schedule, contracted demand, and energy consumption. Therefore, it is difficult to establish real cost savings, especially since the PV system is very small compared to the university’s total demand.

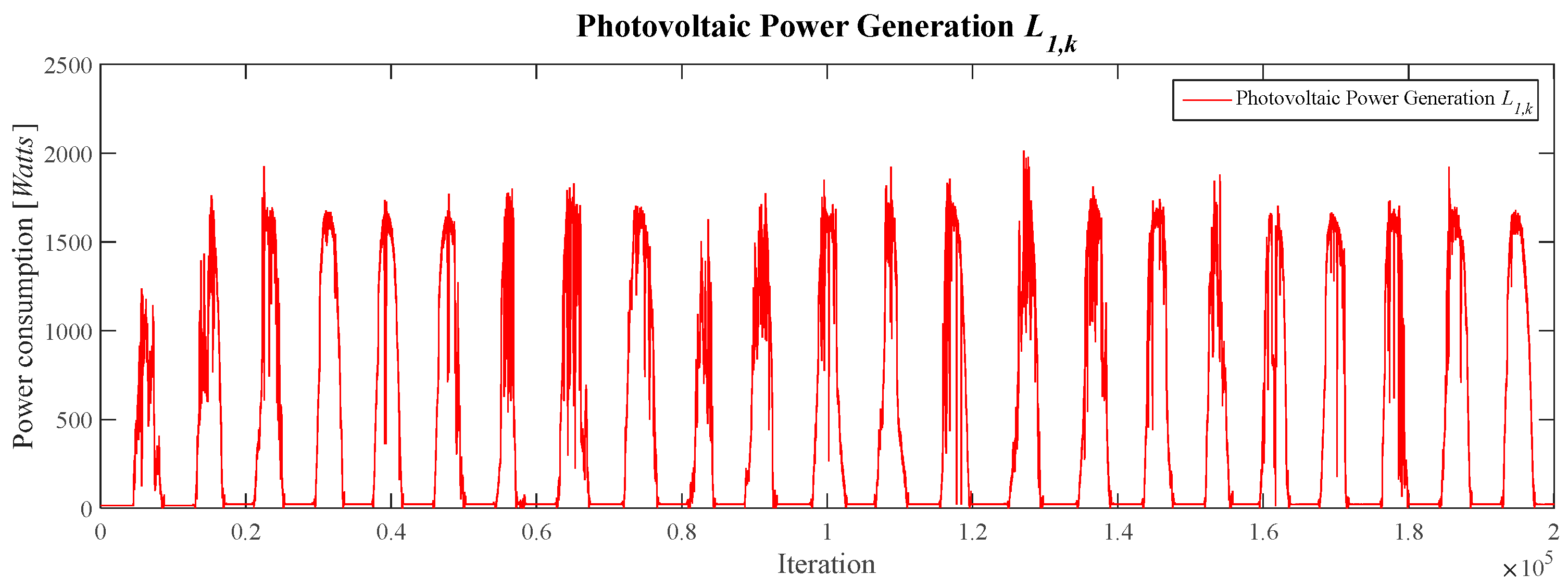

Figure 13 displays the acquired PV Power Generation profile (

L1,k) obtained through the IoT monitoring infrastructure, establishing the dataset that will serve as the foundational case study for the subsequent data reconstruction analysis. The dataset comprises 200,000 samples, corresponding to a 23-day period. The sampling regime yielded 8695 samples per day, 362 per hour, and 6 per minute, indicating a sampling interval of 10 s. Subsequent statistical analysis of the generated power yielded a minimum value of 0.4 W and a maximum of 2013.8 W. In terms of temporary parameters, the Root Mean Square (RMS) value was 767.2913 W, and the average peak height was determined to be 1166.1247 W.

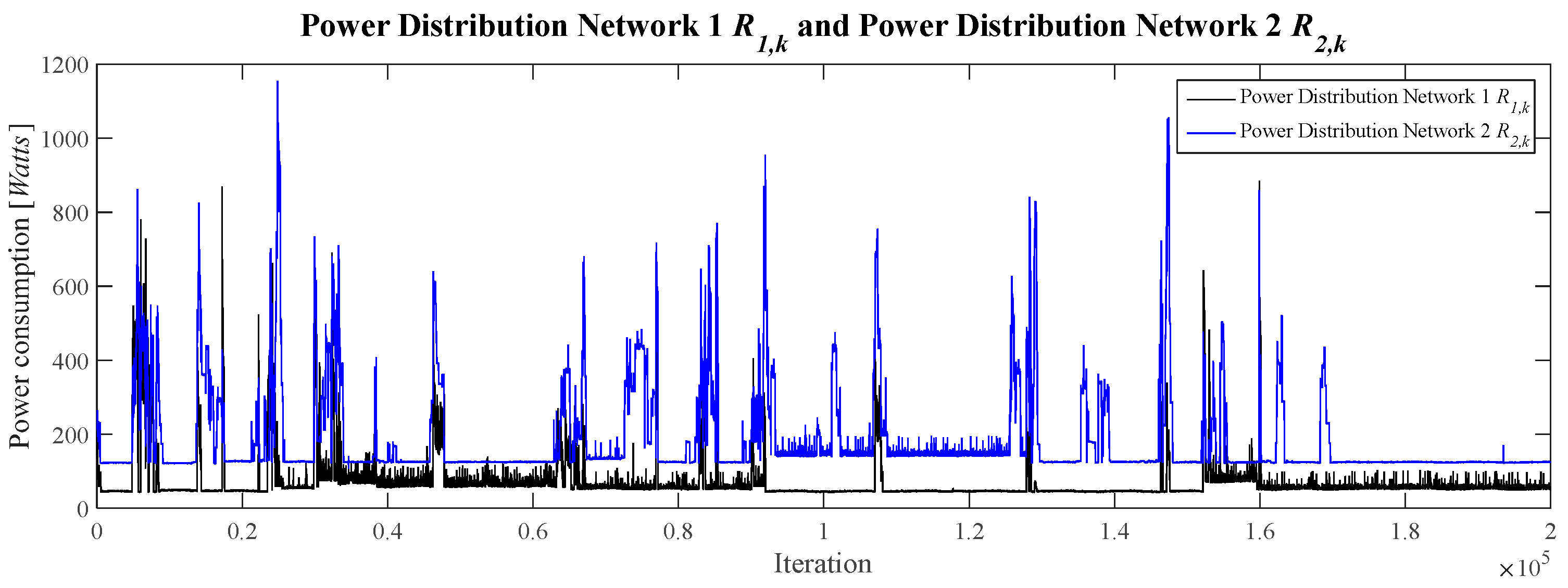

Figure 14 presents the power consumption characteristics of Distribution Network 1 (

R1,k) and Distribution Network 2 (

R2,k), quantifying the energy drawn by the electrical grid. This dataset will form the basis for the subsequent reconstruction procedure using the Kalman filtering methodology. The data acquisition for this dataset also yielded 200,000 samples over a 23-day period, employing a sampling frequency of 0.1 Hz for the distribution network

R1,k and

R2,k. For Distribution Network 1

R1,k, the minimum power observed was 40.9 W and the maximum was 884.9 W, the RMS value is 89.7597 W, and the average peak height is 208.1130 W.

In contrast, for distribution network R2,k, the analysis indicated a minimum power consumption of 106.6 W and a maximum observed value of 1154.5 W. The corresponding Root Mean Square (RMS) value was calculated to be 219.5559 W, with an average peak height of 186.2096 W.

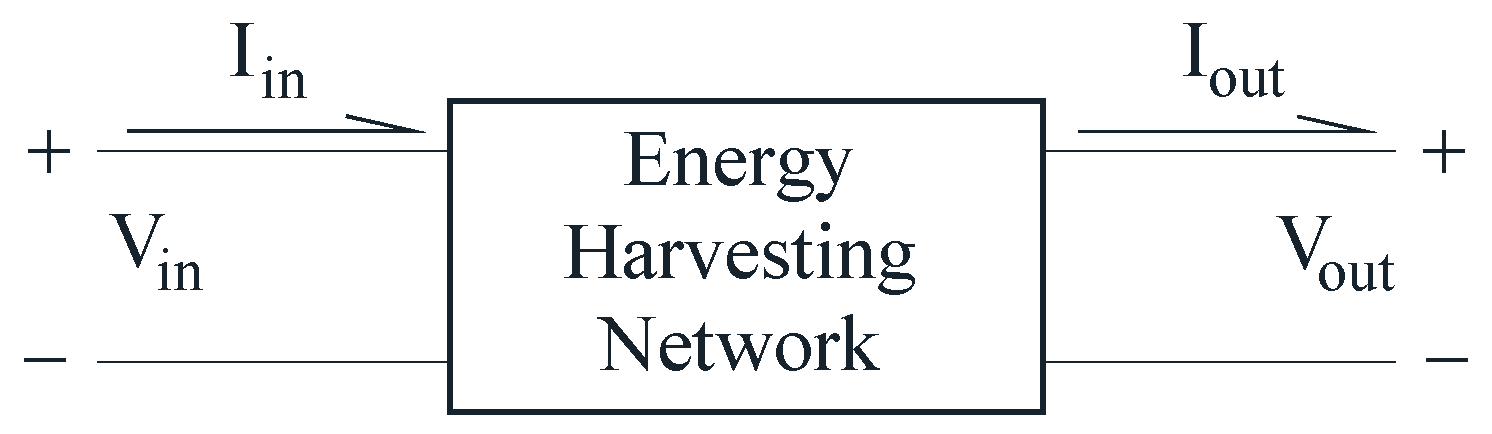

3.3. Characterization of Electrical Parameters SE,k of a Photovoltaic Distribution Network

To ensure the correct operational performance of the Kalman filter in its role as a reconstructor for the behavior of the electrical parameters

SE,k in a PV distribution network, an analysis of the noise covariances is requisite. This entails evaluating the temporary covariance of the process noise,

and the covariance of the output measurement noise,

, associated with PV Power Generation

L1,k, Power Distribution Network 1

R1,k, and Power Distribution Network 2

R2,k. Their functional dependence is ascertained using Equations (9) and (11), and is denoted by Equation (15).

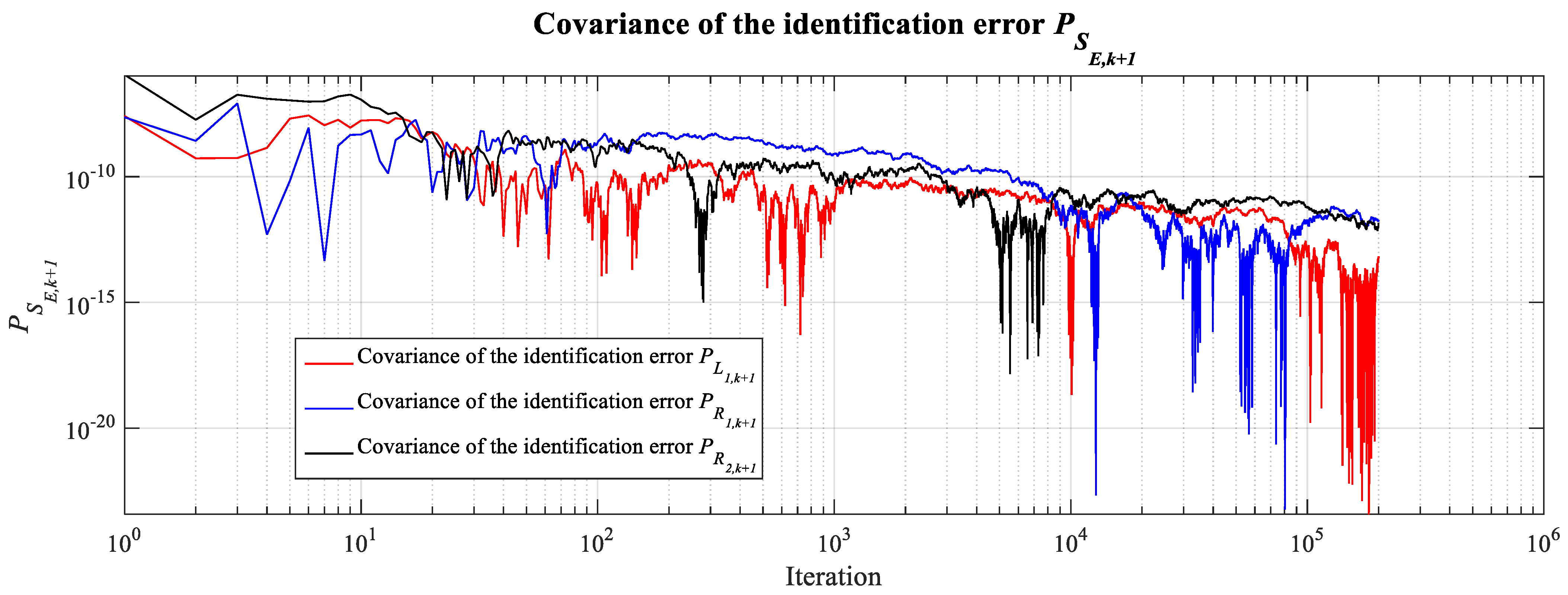

The covariance of the noises associated with the system is presented in

Figure 15.

This figure illustrates the temporary behavior of the noise covariances

,

and

Observation reveals that during the initial phase of system evolution, the covariance behavior exhibits values distinct from zero. This initial behavior allows one to deduce that the noises associated with the system’s input and output exhibit a certain linear dependence at the beginning of the reconstruction process. As the system evolves, however, the temporary covariance of the associated noises is observed to converge gradually towards a value proximate to zero (See

Table 1).

The covariance of the output noise,

, is defined by Equation (16). Its behavior in relation to the system is illustrated in

Figure 16.

A comparable behavior is observed in the output noise covariance,

(see

Table 2 for details). Consequently, it can be established that the input noise covariance

and the output noise covariance

exhibit linear independence.

The property of linear independence allows for the conclusion that the variance of the identification error,

given in (10), is represented by Equation (17). Consequently, this variance will demonstrate the behavior illustrated in

Figure 16.

Based on a detailed analysis of the values compiled in

Table 3, leads to the conclusion that the operational prerequisites for employing the Kalman filter are satisfied. The filter’s capability to accurately reconstruct the behavior of the electrical parameters

SE,k in an IoT monitoring system is thereby established, as the fundamental requirement of linear independence between the system’s input and output noises is assured.

The covariance moment, when assessed through a linear function linking two random processes, is defined within a closed interval ranging from 0 to 1. A value at the left endpoint (0) denotes statistical independence of the processes, whereas a value at the right endpoint (1) signifies a high degree of dependence [

37]. In the context of this system, it is observed that at the start of its operation, the covariance possesses values distinctly different from zero. This initial state implies a measurable level of dependence between the input and output noises during the early stages of reconstruction. As the system continues to evolve, a clear progression is seen: the temporary covariance of the system noises gradually diminishes, tending towards a value close to zero. This observed trajectory demonstrates that the covariances

,

and

correspond to linearly independent noise processes. Our assertion is grounded in the standard metric for linear dependence, where the bounded results within the [0, 1] interval align perfectly with the theoretical framework established in [

37]. This condition ensures a convergent and stable evolution of the identification error covariance.

The apparent convergence of

,

and

to near-zero values in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 could be misinterpreted as numerical underflow. It is pertinent to note that the Kalman filter implementation employed a square-root formulation, ensuring numerical robustness and the preservation of positive definiteness in the covariance matrices. The observed values, documented in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 are significantly above the machine’s underflow threshold (approximately 10

−308 for double-precision arithmetic), making a numerical underflow event highly improbable.

Furthermore, the convergence trajectories of , and exhibit a smooth, asymptotic decay across multiple orders of magnitude, not an abrupt drop. This behavior is characteristic of genuine algorithmic convergence, not numerical instability. Finally, while near-zero covariances could suggest overfitting, this is not the case here. The estimation error covariance remains finite and positive. This is a recognized statistical condition in system identification that occurs precisely when the input and output noises are linearly independent, leaving no cross-correlation for the filter to exploit in further reducing the estimation error.

3.4. Reconstruction of Electrical Parameters SE,k Using Kalman Filter

The establishment of linear independence between the input system noise

and the output system noise

provides the necessary condition to commence the reconstruction of the electrical parameters,

SE,k. To achieve this, it is pertinent to underscore specific additional details regarding the Kalman filter’s implementation. The following description outlines the configuration of the filter’s parameters:

The parameter matrices in Equations (18)–(21) were determined through an iterative model calibration procedure guided by performance metrics. The calibration was performed using the extensive experimental dataset comprising over 256,000 measurements collected during 30 days of continuous monitoring.

The optimization objective was to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) between the reconstructed and measured power trajectories while ensuring stable filter convergence. The diagonal structure of matrices Ak and Bk was chosen to represent the decoupled dynamic behavior observed empirically between the distinct power channels (L1,k, R1,k, R2,k).

The final parameter values were validated by the characteristic MSE convergence profile, which exhibited a consistent negative slope on a log-log scale throughout the system’s temporal evolution. While all states are directly measurable, substantial noise contamination renders their true values effectively hidden, thus requiring optimal estimation. The identity matrix Ck represents this direct measurability while enabling the Kalman filter to estimate the true states from noisy measurements.

In the state-space formulation (Equation (3)), the term BkUk represents measurable exogenous inputs that influence system dynamics, including environmental conditions and grid-side perturbations. The vector Uk contains normalized operating points derived from experimental data, representing typical coupling coefficients between generation and distribution channels under standard operating conditions. Uk represents measurable exogenous inputs that influence the system dynamics, specifically the Environmental conditions (as irradiance, temperature), Grid-side influences (as voltage fluctuations, frequency variations) and Load variations in the distribution networks.

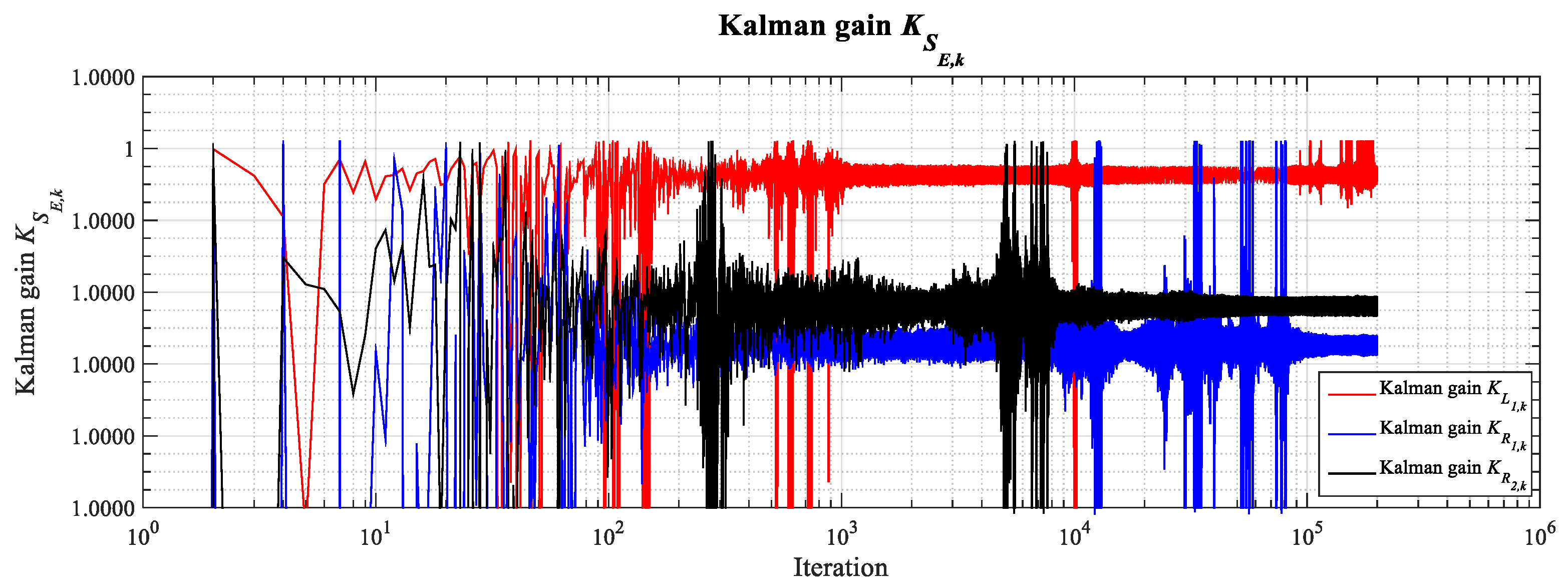

Consequently, Equation (7), which is rewritten as (22), may be employed to calculate the Kalman gain, denoted as

and illustrated in

Figure 17. This gain facilitates the reconstruction of the following electrical parameters: PV Power Generation

L1,k, Power Distribution Network 1

R1,k, and Power Distribution Network 2

R2,k.

Inspection of

Figure 17 reveals that the gain

attains values in close proximity to unity. These transient peaks in gain coincide with periods of high uncertainty in the state estimate, as quantified by

. Under such conditions, it is expected that the filter will assign greater weight to the incoming measurements to facilitate a rapid correction of the state estimate.

Nevertheless, as the filter proceeds towards convergence and the error covariance

diminishes (see

Figure 16), the gain

does not persist at a value of one. Rather, it stabilizes at a significantly lower value, thereby demonstrating that subsequent to initialization, the filter establishes and sustains an appropriate equilibrium between the internal model and the external measurements. It is within this steady-state regime that the convergence of

,

to near-zero values is observed, thereby countering the proposition that this phenomenon is driven by persistent and uncritical reliance on the measurements.

To prevent the potential for overfitting in , the identified model was subjected to validation using an independent hold-out dataset, which was not utilized during the identification process. The model exhibited consistent performance on this validation set, with no significant degradation in predictive error. This outcome confirms that the model has successfully captured the underlying system dynamics and is not merely overfitted to the training data.

Figure 18 presents a visual comparison, contrasting the directly measured values of PV Power Generation

L1,k with the values reconstructed by the filter

.

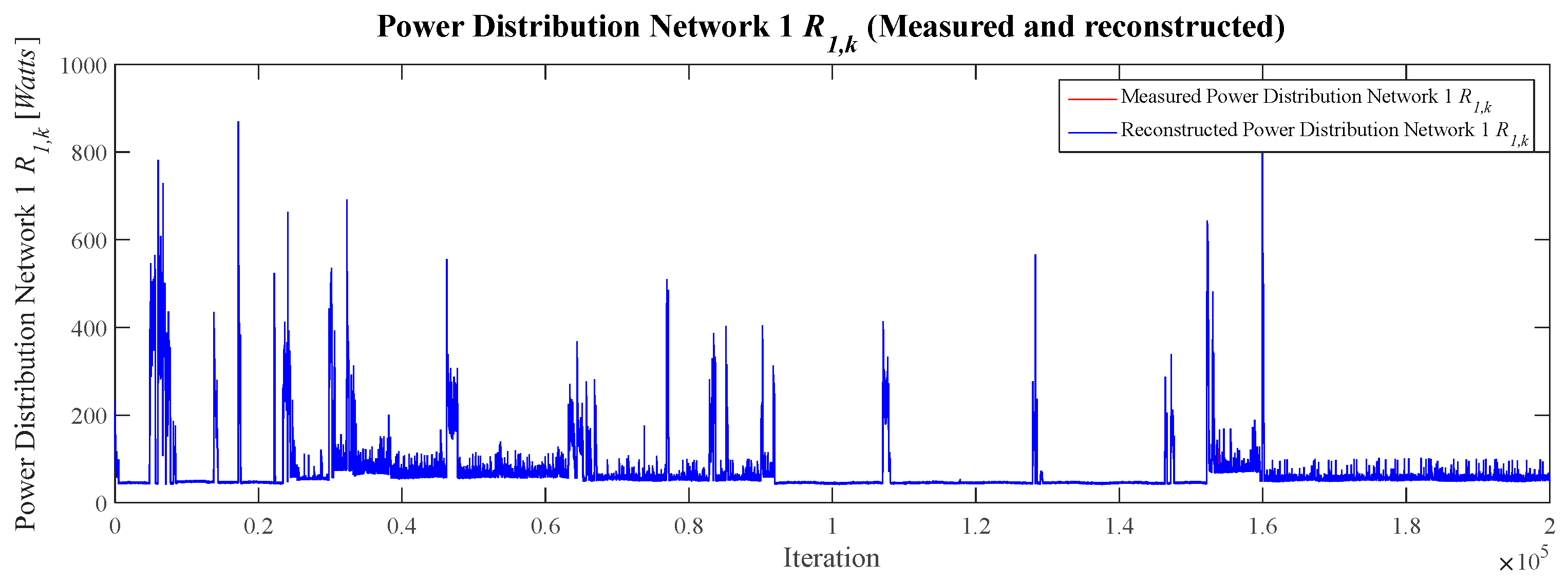

The visual comparison in

Figure 19 allows for the observation of both the measured Power Distribution Network 1

R1,k and the reconstructed Power Distribution Network 1

. Analysis of the figure reveals that the reconstructed profile successfully captures the same behavioral dynamics as the measured power signal.

The measured values for Power Distribution Network 2

R2,k and their reconstructed

are presented together in

Figure 20. Upon examining the behavioral trends of both, it is evident that the reconstructed output converges with the measured data across almost the entire range. This high degree of alignment demonstrates that there is no meaningful difference between the two.

Similarly to the results for

, the reconstructed values for

and

exhibit a very high degree of precision, aligning closely with the electrical parameters measured

SE,k throughout the whole range of

k. Nevertheless, this qualitative assessment is deemed insufficient for robust validation. This necessitates the use of descriptive statistical measures, including the first and second-order moments of probability and the mean squared error, to provide a robust validation of the reconstruction’s performance. A comparison of the first-order probability moment, or expected value

E{

SE,k}, for the actual and the reconstructed electrical parameters is provided in

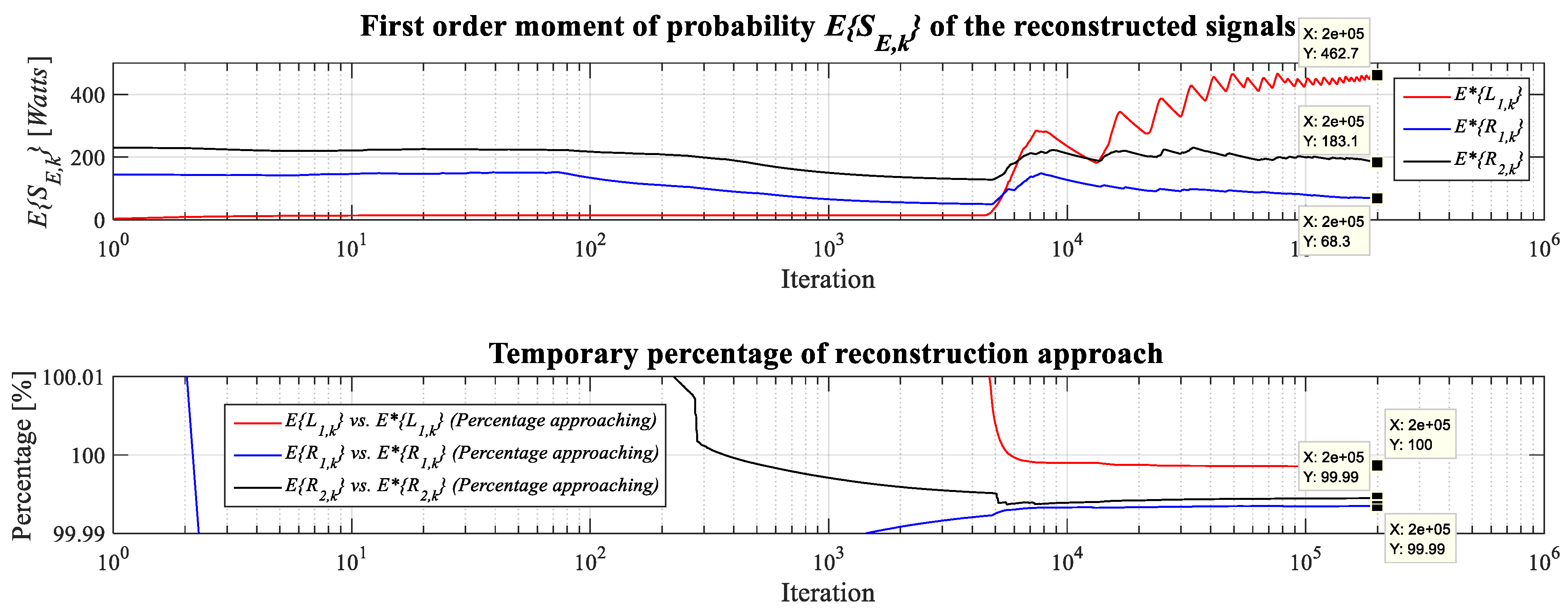

Figure 21, offering further insight into their statistical behavior.

The behavior of the second-order probability moment,

E{

SE,k}

2 pertaining to both the actual and reconstructed electrical parameters, is illustrated in

Figure 22.

The analysis reveals that the initial phase of communication with the IoT monitoring system, implemented via the Thingsboard platform [

33], is characterized by a noticeable divergence in the second-order probability moment of the reconstructed electrical parameters

compared to the real values. Despite this initial discrepancy, the system’s performance improves markedly over time, with the reconstructed values achieving a convergence very close to 100% relative to the actual measurements at the vast majority of points.

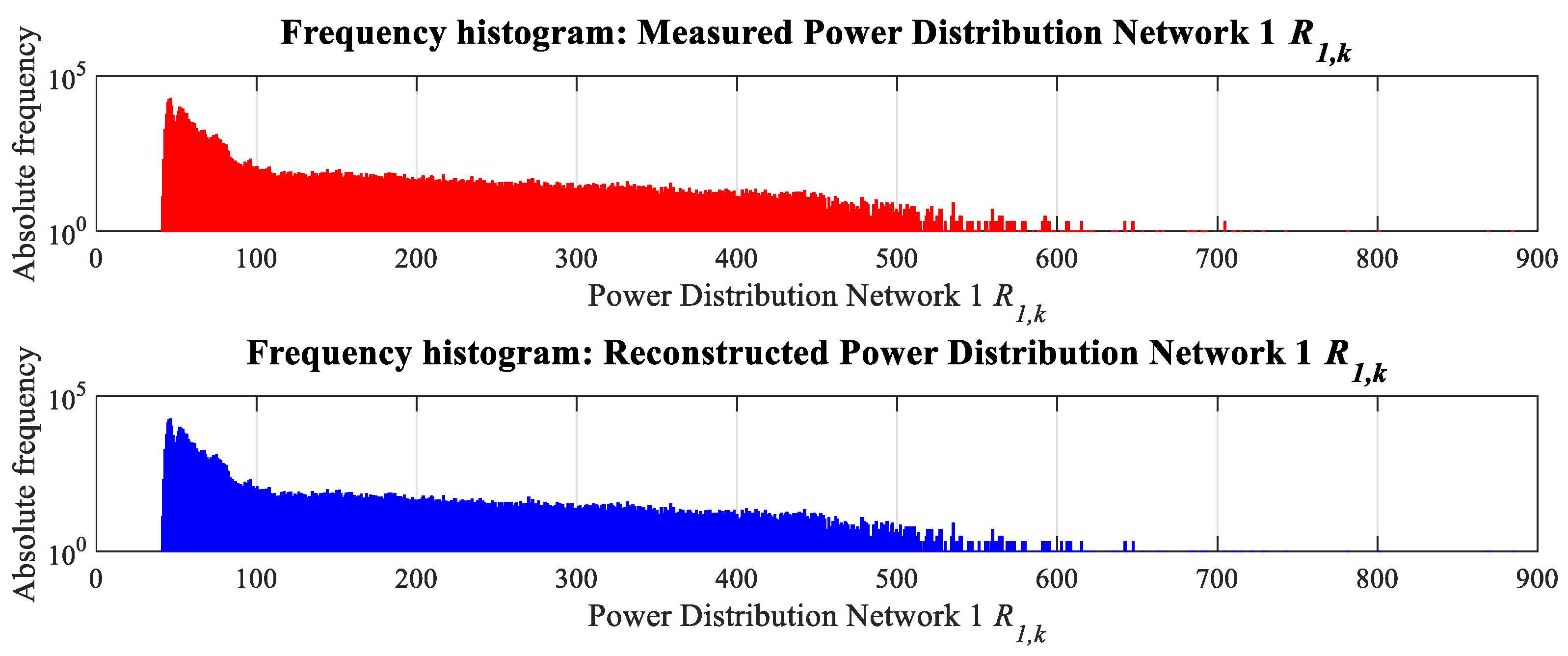

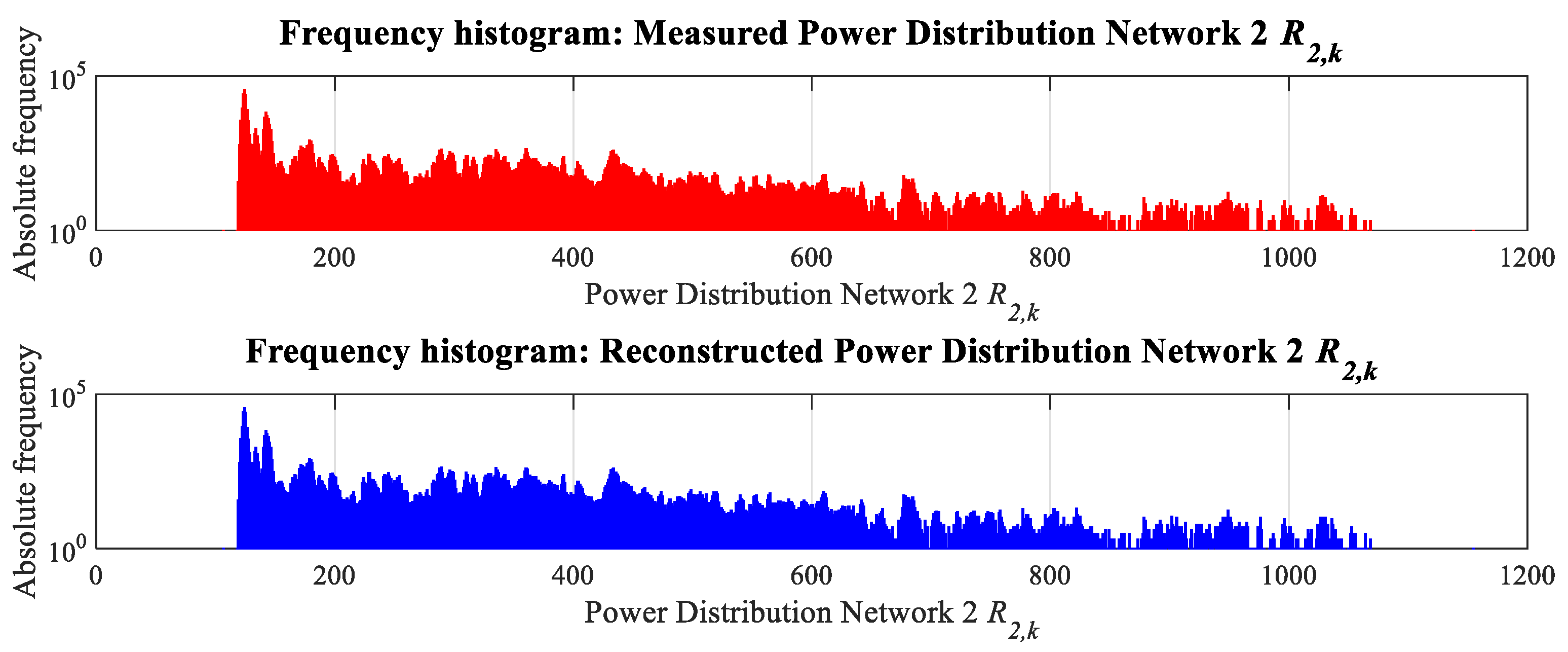

To rigorously assess the statistical consistency between the measured and reconstructed signals, it is essential to analyze their corresponding probability distribution functions (PDFs). A graphical comparison of PDFs provides an intuitive visual representation of how effectively the reconstruction preserves the overall statistical structure of the data [

38]. The probability density function was estimated by computing the frequency distribution of the electrical power data via histograms. Histograms allow the identification of underlying data patterns by grouping observations into a finite number of non-overlapping intervals (bins), which removes any ambiguity in class assignment for each observation.

However, visual inspection alone is insufficient for a robust evaluation; therefore, we complement the PDF plots with quantitative descriptive metrics as the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic. The combination of this metric with PDF visualization offers comprehensive validation encompassing both visual perception and statistical rigor, thereby ensuring that conclusions regarding linear independence and model accuracy are robustly substantiated [

38].

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic quantifies the maximum discrepancy between the cumulative distributions, offering a global measure of similarity, while its associated

p-value contextualizes the statistical significance of this discrepancy [

39]. It can be characterized through the application of Equation (23).

where

pi is the PDF measured and

qi is the PDF reconstructed.

Equation (23) is reformulated as (24). Upon applying this metric to the probability density functions (PDFs) of

L1,k,

R1,k, and

R2,k, the results presented in

Table 4 were obtained.

The obtained KS values quantify the maximum absolute distance between the empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of the measured and reconstructed signals. Critically, all values lie significantly below the standard threshold of 0.2, which, according to the established criteria in [

39], indicates a high degree of distributional similarity. These results collectively provide robust quantitative validation that the reconstruction algorithm successfully preserves the core statistical identity of the original signals.

The mean squared error between the actual electrical parameters

SE,k and their reconstructed electrical parameters

can be characterized by describing the convergence of the filter through the application of Equations (25) and (26), proceeding until the minimum magnitude of

is attained.

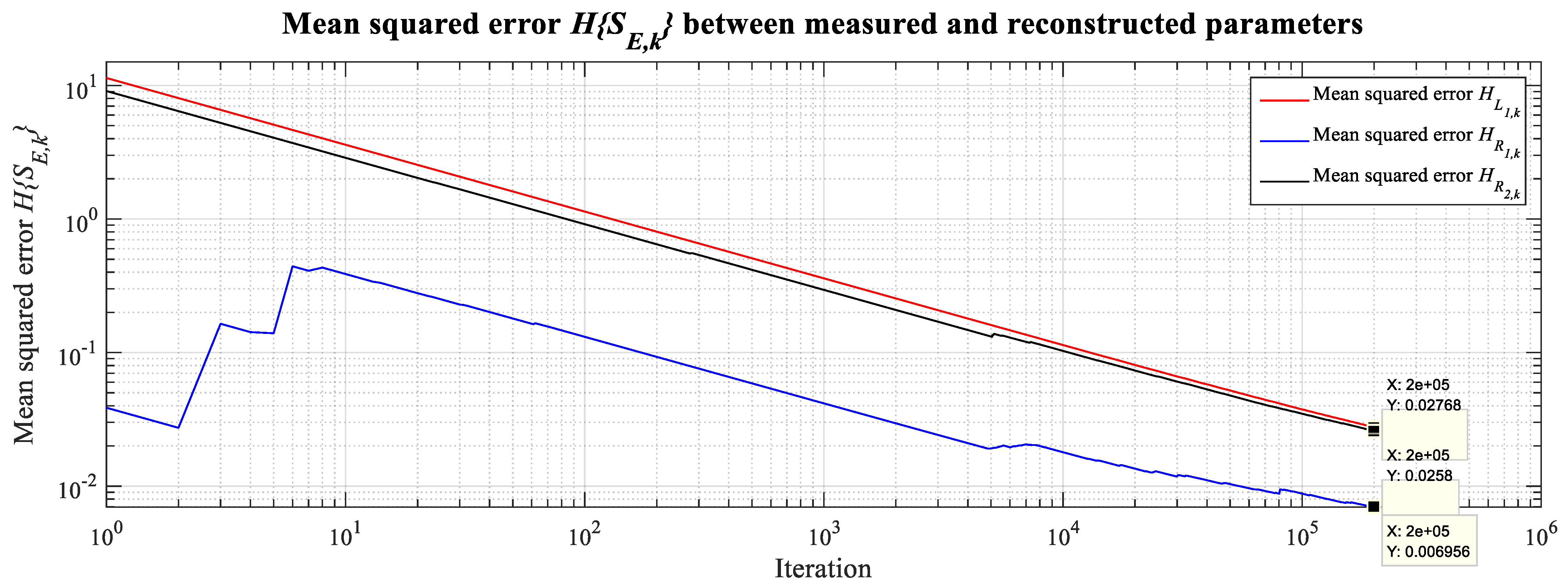

The results presented in

Figure 26, which are derived from Equation (26) (reformulated as Equation (27)), indicate that the Kalman filter exhibits a high degree of convergence across the vast majority of data points. This conclusion is drawn from the behavior of the mean squared error,

, which converges to notably small magnitudes for the electrical parameters

SE,k (a finding supported by the data in

Table 5). The magnitude of this error is a direct indicator of reconstruction quality, whereby smaller values of

correspond to a more accurate and faithful reconstruction of the original parameters.

4. Discussion

The operational profile of a PV system, denoted by its power generation L1,k, is characterized by significant fluctuations and periods of intermittency. This behavior originates from a multitude of external determinants (including the site’s geographic and climatic context, seasonal and diurnal cycles, and immediate terrain), coupled with internal system attributes such as the specifications and condition of the solar cells, their installation parameters, and various loss mechanisms like shading, soiling, and inefficiencies in power electronics and wiring.

The temporary dynamics of Power Distribution Network 1 (R1,k) and Power Distribution Network 2 (R2,k) within IoT monitoring systems exhibit variations attributable to multiple influencing factors. These encompass long-term technological infrastructure development, periodic seasonal and diurnal patterns, regular cyclic components, and irregular stochastic fluctuations. Such complex temporary characteristics necessitate advanced reconstruction methodologies, particularly Kalman filtering, which optimally distinguishes the genuine power trajectory from measurement noise and random disturbances in photovoltaic-integrated distribution networks.

Following the previously described architecture, this manuscript employs a modular client-server communication scheme to acquire electrical parameters via an IoT monitoring system. The developed platform implements a two-layer architecture consisting of (a) an Edge Layer (Data Acquisition), responsible for real-time measurement of electrical parameters, and (b) a Cloud Layer (Visualization/Analysis), dedicated to data monitoring and processing.

The server-side implementation was realized on the Cloud Layer for platform integration and visualization. The integration of the ThingsBoard IoT platform was a crucial component for real-time monitoring and data management. Using the MQTT protocol, the platform enabled the continuous acquisition, visualization, and storage of key electrical variables, including voltage, current, power, energy, frequency, and power factor. Customized dashboards provided an intuitive interface for data interpretation and allowed for the simultaneous monitoring of multiple network nodes. Experimental evaluation demonstrated that the platform maintained stable communication with a data refresh rate of approximately 10 s, ensuring minimal packet loss and reliable data integrity. Interactive widgets, such as line charts, gauges, and digital indicators, enhanced the capacity for detecting transient events and analyzing long-term performance trends. Furthermore, the configuration of automated alerts for communication loss or abnormal readings improved overall system reliability and response time.

The client-side implementation was executed on the Edge Layer for data acquisition and processing. The developed measurement device successfully achieved accurate real-time data acquisition for evaluating photovoltaic and grid-connected systems. The hardware architecture, based on ESP8266 microcontrollers and PZEM-004T-100A sensors, enabled precise measurement of voltage, current, active power, energy, frequency, and power factor across three independent channels.

To improve the justification for the proposed IoT platform architecture, the layer structure was aligned with the five-layer IoT architecture commonly described in the recent literature (Perception, Network, Middleware, Application, Business) [

40], as referenced in similar PV monitoring frameworks. Although the present work implements only the functional layers directly required for real-time photovoltaic data acquisition and cloud visualization, the design process followed the logic of this established model to ensure modularity, scalability, and a clear separation of responsibilities. Specifically, the Perception Layer corresponds to the sensing hardware (PZEM-004T-100A modules), the Network Layer is implemented via Wi-Fi communication and MQTT transport, and the Processing/Application Layers are integrated within the ThingsBoard cloud environment for data storage, analysis, and dashboard visualization. The Business Layer, which is focused on long-term analysis, decision-making, and system optimization, was not implemented because the project scope was limited to operational monitoring and validation of the Mexican inverter prototype. This adaptation is consistent with the five-layer architecture referenced in [

40], but it also reflects practical limitations such as hardware confidentiality, available network infrastructure, and the initial nature of the implementation.

Experimental validation confirmed high repeatability and accuracy, with deviations remaining below ±2% compared to calibrated reference instruments. The design prioritized low cost, modularity, and ease of wireless integration, facilitating deployment in remote or dynamic environments, a key requirement for testing PV inverters and distributed generation systems. The embedded firmware efficiently managed sensor communication, error correction, and data packaging into JSON format for transmission to the ThingsBoard platform. This architecture proved robust during continuous operation, exhibiting stable network connectivity and minimal energy consumption.

Once linear independence of the noises associated with input system and output system was ensured, the Kalman filter was used as one part of a reconstructor of electrical parameters SE,k of a monitoring IoT system of electrical parameters. For this reason, it was necessary to analyze the covariance of input noise and the covariance of output noise in PV Power Generation L1,k, Power Distribution Network 1 R1,k, and Power Distribution Network 2 R2,k. Then it is possible to use Equation (7) to calculate the Kalman’s gain , which will allow the reconstruction of PV Power Generation L1,k, Power Distribution Network 1 R1,k, and Power Distribution Network 2 R2,k.

However, although a comparative analysis was not conducted in this case using other network and communication topologies, as well as different hardware and software resources for data acquisition, remote transmission, and storage, it should be mentioned that the possibility of carrying out such a study is imminent and can be considered as future work.

Regarding the use of the KF as a tool for data reconstruction and filtering, works such as those by [

14,

16] leveraged the properties of the KF to perform real-time measurement filtering. In this sense, their strategy involves simplifying the KF algorithm so that the calculations performed in this segment of the code do not introduce significant delays that would impact the required sampling period and cause the loss of relevant information. However, in the present work, an offline analysis was conducted, using the acquired data and processing it on a computer. Consequently, the computational complexity of the data-cleaning process using the KF did not affect the results obtained during the experimental tests.

Likewise, in works such as that by [

17], the author carried out an analysis of datasets using the KF to eliminate noise and other alterations that generate deviations preventing the extraction of useful results about the phenomena the data might represent.

From a broader perspective, in this work the authors have focused on demonstrating the relevance of using the KF as a reconstructor of both transient and steady-state phenomena in the electrical parameters measured from a low-power photovoltaic system via an Internet of Things (IoT)-based data acquisition system. In doing so, the authors highlight the relevance of the KF when operating on data obtained from a PV system functioning under nominal conditions in a real, practical environment.

The validation of results in this work is corroborated through three descriptive measures: probability moments, probability distribution, and the mean square error. Collectively, these serve as global performance indicators for the reconstruction of the electrical parameters. The first measure involves the analysis of probability moments for both the original and the reconstructed electrical parameters. The comparative analysis, vividly captured in

Figure 21 and

Figure 22, demonstrates a clear convergence of these moments towards similar values. This convergence provides a strong, foundational argument that the reconstruction has been achieved with high fidelity. Furthermore, the probability distributions of the data are examined. Illustrated through the histograms in

Figure 24 and

Figure 25 for Power Distribution Network 1

R1,k, and Power Distribution Network 2

R2,k, these graphs effectively group data into precise, non-overlapping classes to reveal underlying patterns. The close visual agreement between the measured and reconstructed histograms reflects a nearly identical probability distribution across different power levels. This observation is statistically corroborated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test. The low KS values obtained for

R1,k (0.0117) and

R2,k (0.0191) indicate an exceptionally close match between the distributions. Although slightly higher, the KS value for

L1,k (0.129) still falls within a range that denotes satisfactory agreement. Together, these quantitative results confirm that the reconstruction algorithm faithfully preserves the statistical distribution of the original signals.

Finally, the behavior of the mean square errors, governed by Equations (15) and (16) and graphically represented in

Figure 26, shows a definitive asymptotic convergence to zero. This trend offers a conclusive performance indicator, independently confirming the high quality of the reconstruction and seamlessly aligning with the evidence provided by the moment-based and distribution-based analyses.

It is observed that during the initial communication attempts with the IoT monitoring system, the second-order moment of probability for the reconstructed electrical parameters

exhibits a degree of divergence from the actual values. As the system evolves, however, the convergence towards the true values approaches 100% at nearly all data points.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated a Kalman Filter (KF)-based reconstruction technique for photovoltaic (PV) systems using data from a custom IoT monitoring platform. The implementation was based on a two-layer IoT architecture (Edge and Cloud) for real-time data acquisition and visualization.

The principal contribution is the development of an adaptive dual KF system specifically designed for the PV environment, which introduces three key innovations: first, an online, adaptive noise covariance estimation mechanism that continuously identifies and updates the process and measurement noise statistics in real-time, overcoming the standard KF assumption of fixed covariances and enabling robust handling of the non-Gaussian, intermittent noise inherent to PV systems. Second, the integration of complete trajectory reconstruction with system parameter identification, allowing the model to be refined concurrently with signal filtering. Third, a lightweight computational implementation designed for execution on resource-constrained IoT edge devices. The successful integration of a Kalman Filter-based reconstruction system into a practical IoT monitoring system for PV installations provides a robust methodological alternative to obtain high-fidelity power trajectories, essential for accurate performance monitoring, fault detection, and energy forecasting in smart grids.

The results show that the KF successfully reconstructed the power trajectories with high fidelity, validated by the asymptotic convergence to zero of the Mean Squared Error and near-perfect alignment in probability moments and distribution functions. This confirms that the algorithm preserves the statistical identity of the signals while suppressing noise. Future research could incorporate a comparative analysis with other communication topologies (such as LPWANs like LoRaWAN) and alternative filtering methods to establish more comprehensive benchmarks. Furthermore, while the presented design aligns with the established five-layer IoT model (Perception, Network, Middleware, Application, Business), the current implementation focuses on the operational layers (Perception through Application). Extending the system to incorporate the Business Layer, with functions for advanced analytics, predictive maintenance, and decision support, remains a critical step toward maximizing the value of the monitored data.