Moving-Block-Based Lane-Sharing Strategy for Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit with a Leading Eco-Driving Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A moving block-based lane-sharing strategy is proposed for ART dedicated lanes. The strategy authorizes lane access according to real-time remaining green time, avoiding forced clearance and signal coordination and thus reducing impacts on non-ART vehicles.

- (2)

- An ART-led eco-driving control framework is developed, which not only provides a stop-free eco-driving trajectory for ART but also improves mixed traffic efficiency through vehicle-following behavior.

- (3)

- A modified trajectory optimization algorithm is designed that transforms the highly nonlinear programming into a state-space search problem. With a state-space reduction algorithm, the solution achieves a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy.

- (4)

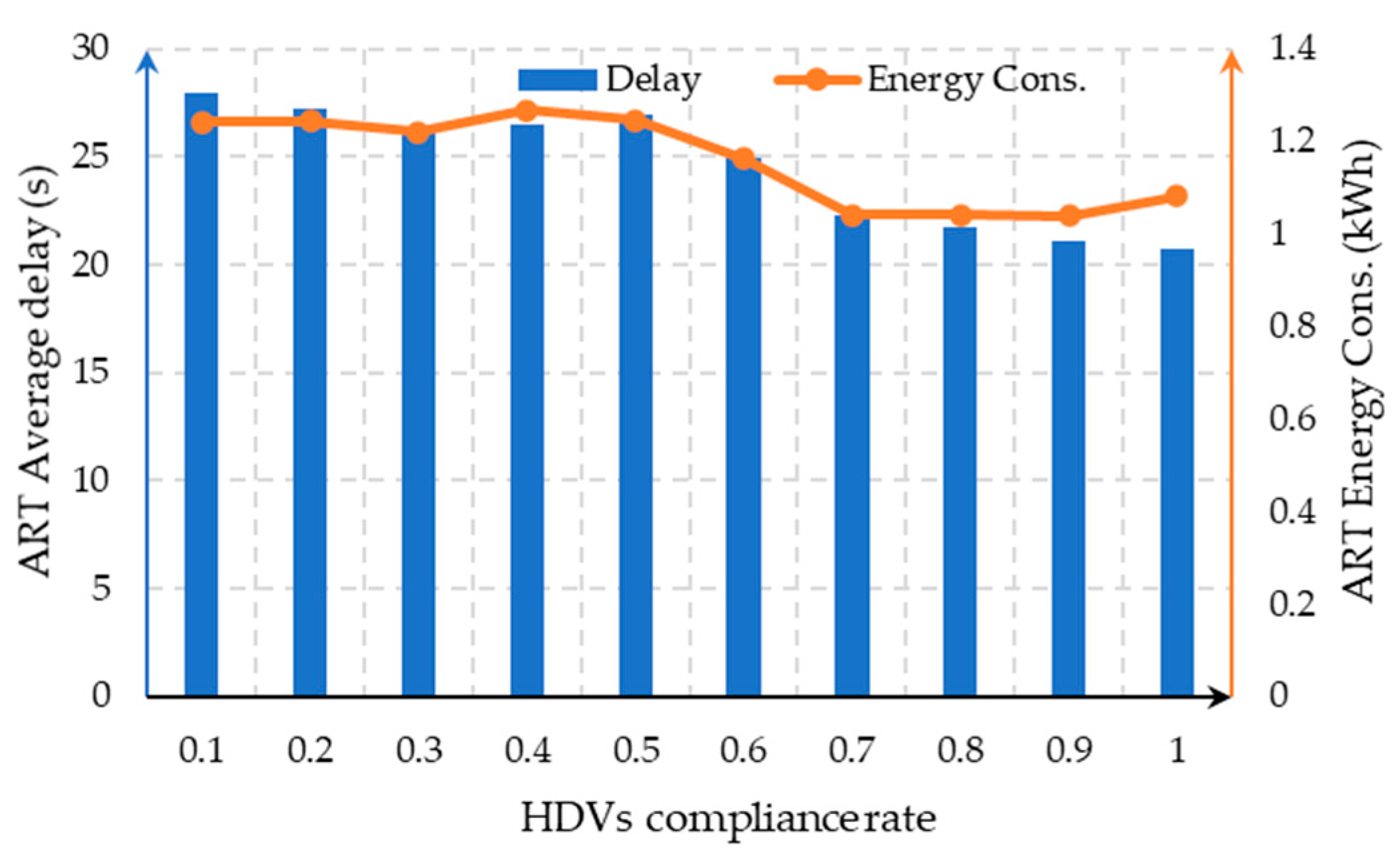

- The compliance behavior of non-ART vehicles is analyzed. A key challenge in lane-sharing scenarios is the compliance of non-ART vehicles with block control rules. Simulation results show that when the compliance rate of non-ART vehicles exceeds 60%, ART operational efficiency is largely maintained.

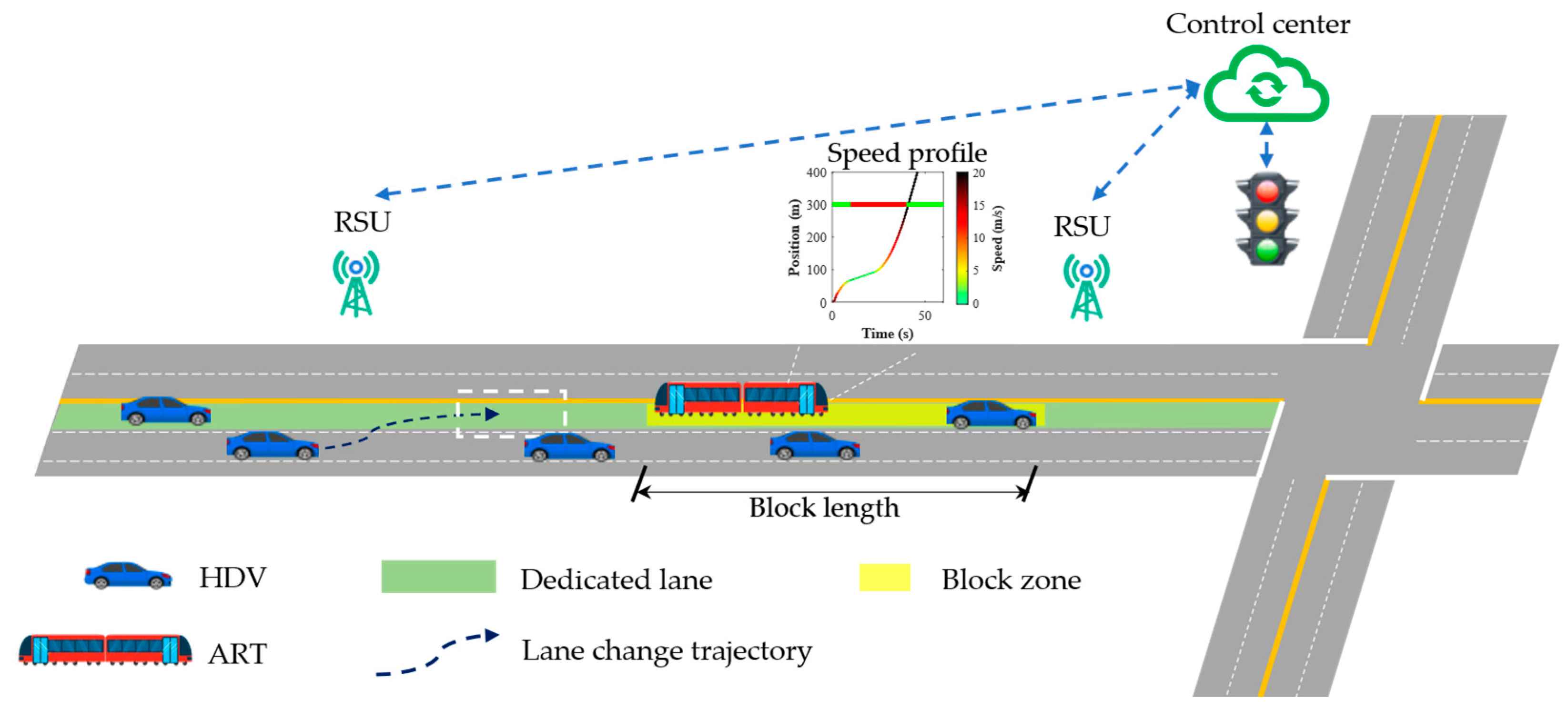

2. Problem Description and Assumptions

2.1. Problem Description

- (1)

- How to update the moving-block zone for non-ART vehicles without compromising the operational efficiency of ART. In addition, signal coordination and forced lane clearance are not preferred options, as they may impose adverse effects on the overall traffic flow.

- (2)

- How to generate eco-driving trajectories for ART vehicles that achieve a trade-off between computational efficiency and solution accuracy.

2.2. Assumptions

- (1)

- The communication system is ideal, with no delays, packet loss, or failures; all data exchange is real-time and reliable.

- (2)

- Non-ART vehicles have higher desired speeds than ART but remain below the speed limit, and travel at the maximum allowable speed when unimpeded.

- (3)

- Non-ART vehicles comply with ART right-of-way signals [20]. The following sections examine the compliance rate of non-ART vehicles.

- (4)

- All non-ART vehicles are assumed to be homogeneous in physical characteristics (e.g., size and dynamics), as heavy trucks are generally prohibited from operating on urban roads during daytime.

3. Moving Block Control System for ART

3.1. Moving Block Control Methodology

3.1.1. Red Safety Block

3.1.2. Yellow Buffer Block

3.1.3. Green Free Block

3.2. Operating Rules for Non-ART Vehicles

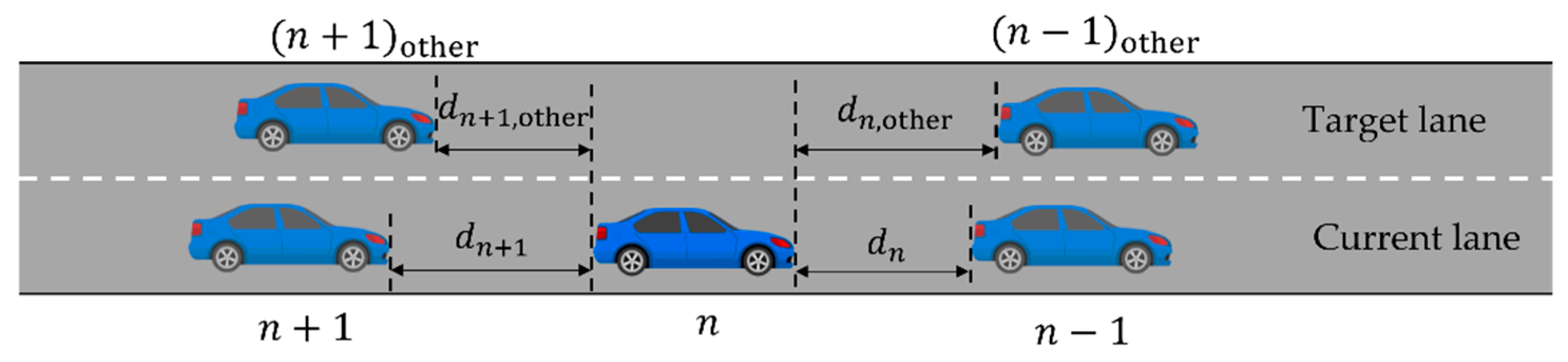

3.2.1. Voluntary Lane Changing

- Lane-changing incentive

- Safety condition

- Block-aware constraint

- Lane-changing probability

3.2.2. Mandatory Lane Exit

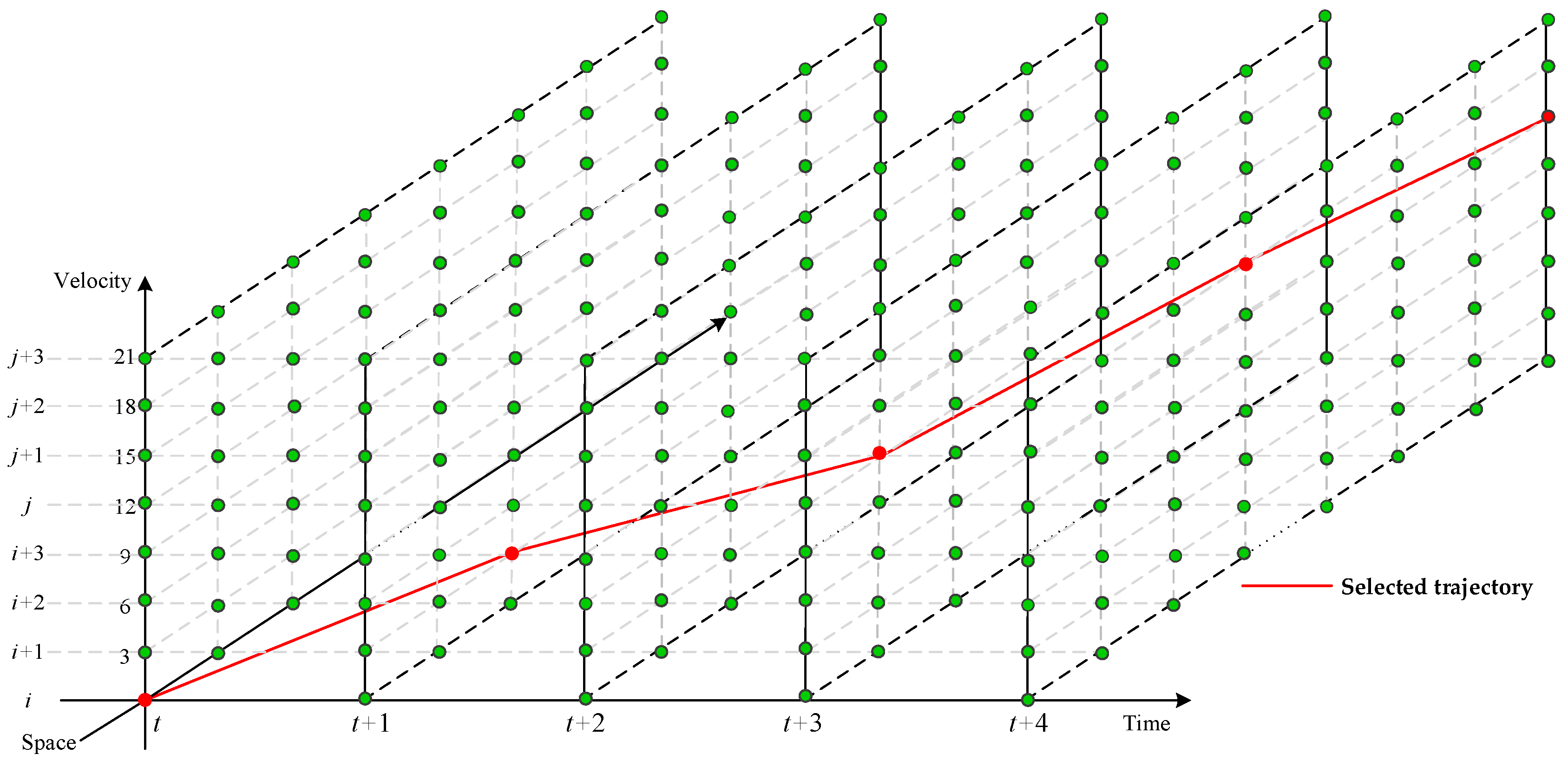

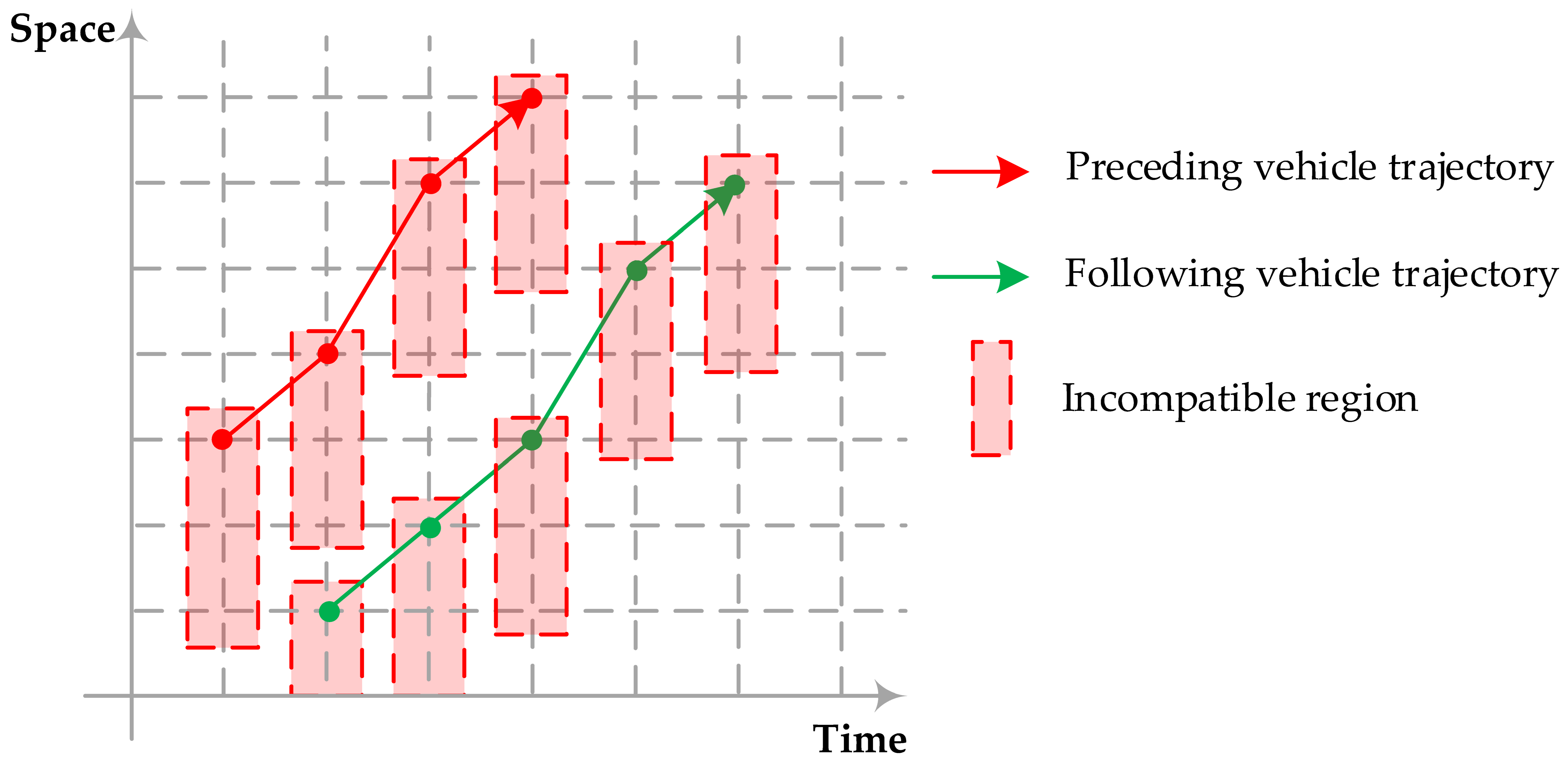

4. Eco-Driving Modeling for ART Based on Time–Space–State Network

4.1. Model Formulation

4.1.1. Energy-Efficient Trajectory Optimization Based on Optimal Control

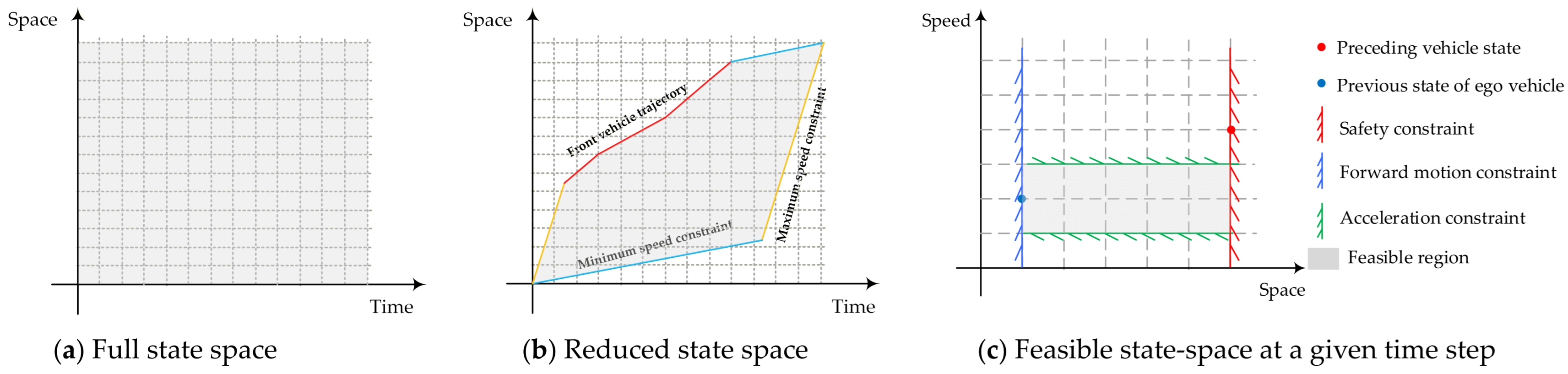

4.1.2. Improved Trajectory Optimization Model Based on the Space–Time–State Network

4.2. Energy Consumption Model for ART

4.3. Fuel Consumption Model for Non-ART Vehicles

5. Solution Algorithm and Control Framework

5.1. Solution Algorithm

| Algorithm 1. ART trajectory optimization via dynamic programming with state-space reduction | |

| Input: Initial state ; signal timing; model parameters | |

| Output: Optimized trajectory (state and control sequence) | |

| 1 | Initialization |

| 2 | Initialize for all , , |

| 3 | Set ; set predecessor |

| 4 | Dynamic programming recursion |

| 5 | for each do |

| 6 | feasible state set at time satisfying safety constraints and speed limits |

| 7 | for each do |

| 8 | admissible acceleration set under vehicle dynamics |

| 9 | for each do |

| 10 | , |

| 11 | if is feasible then |

| 12 | |

| 13 | if , then |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | end if |

| 17 | end if |

| 18 | end for |

| 19 | end for |

| 20 | end for |

| 21 | Termination and backtracking |

| 22 | over feasible terminal states |

| 23 | Recover the optimal trajectory and control sequence by backtracking via |

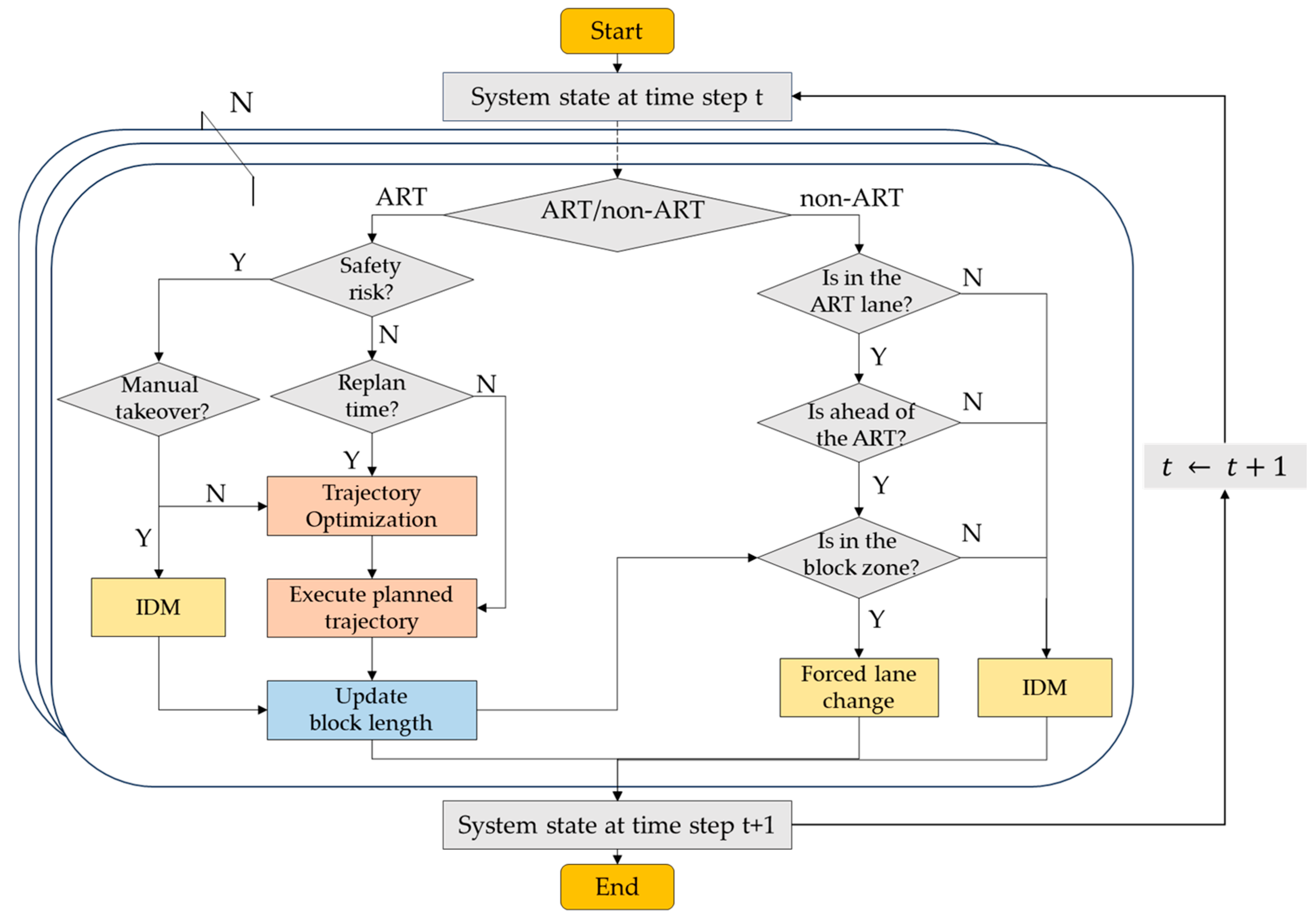

5.2. Control Framework

6. Simulation Experiments

6.1. Parameter Settings

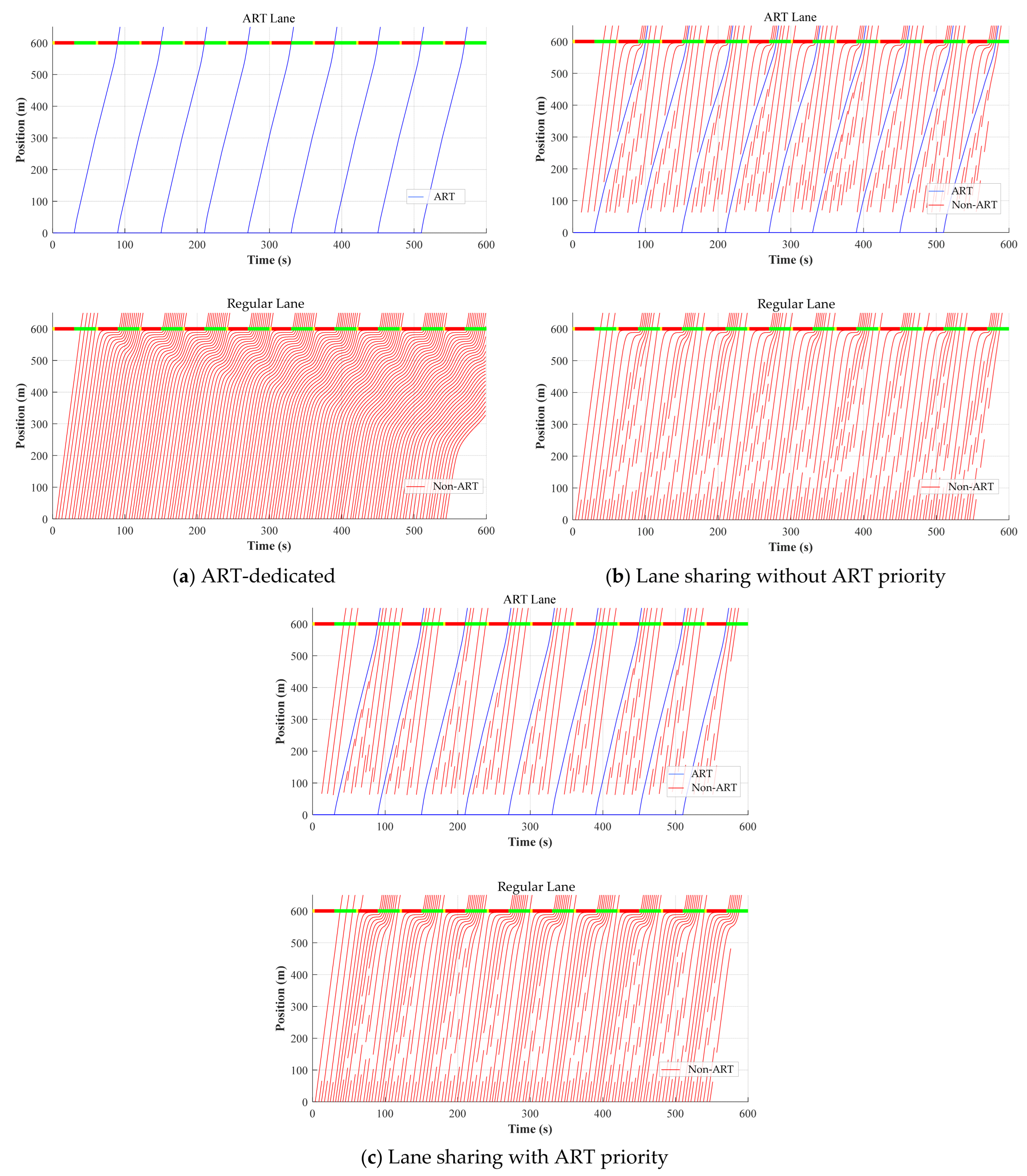

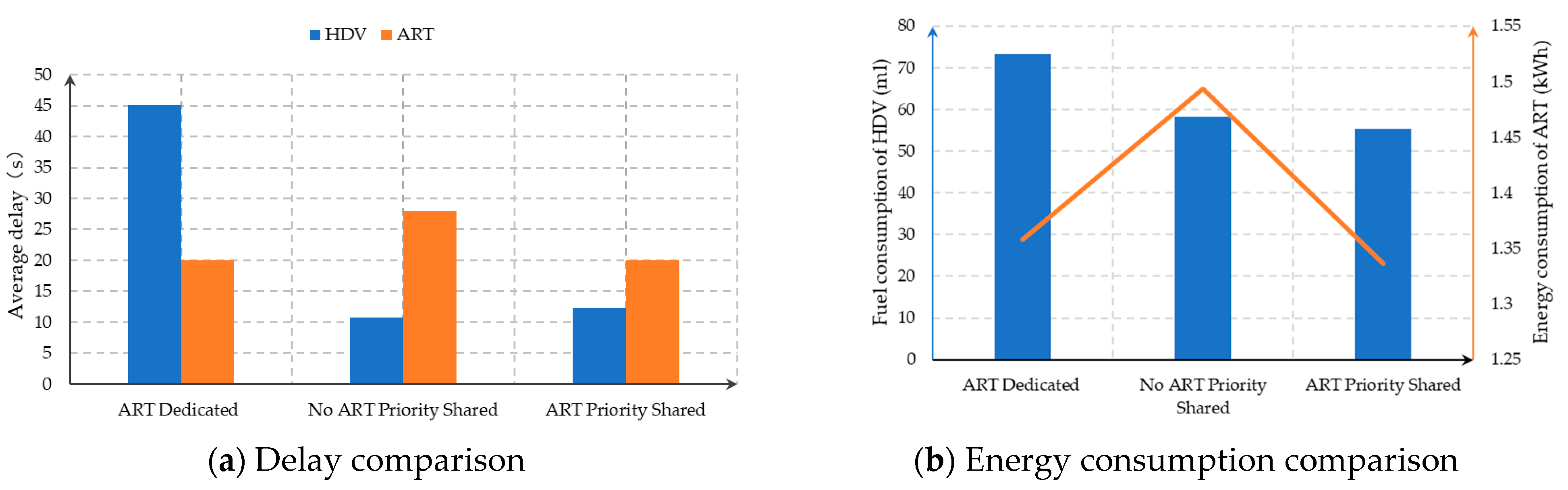

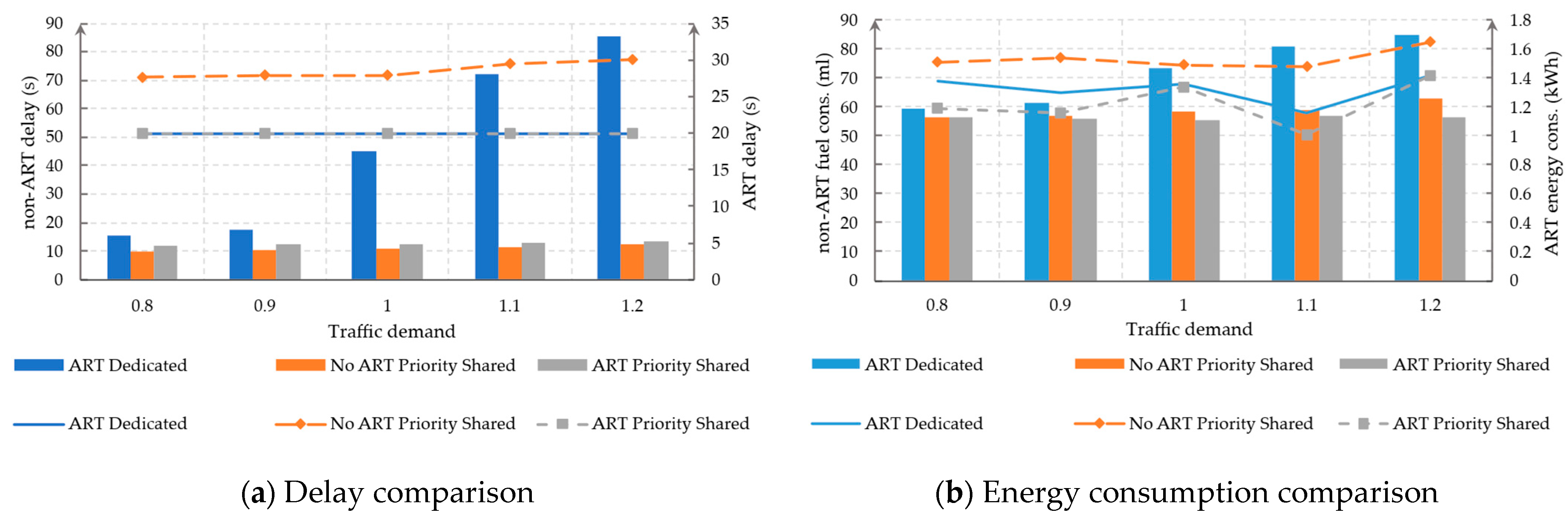

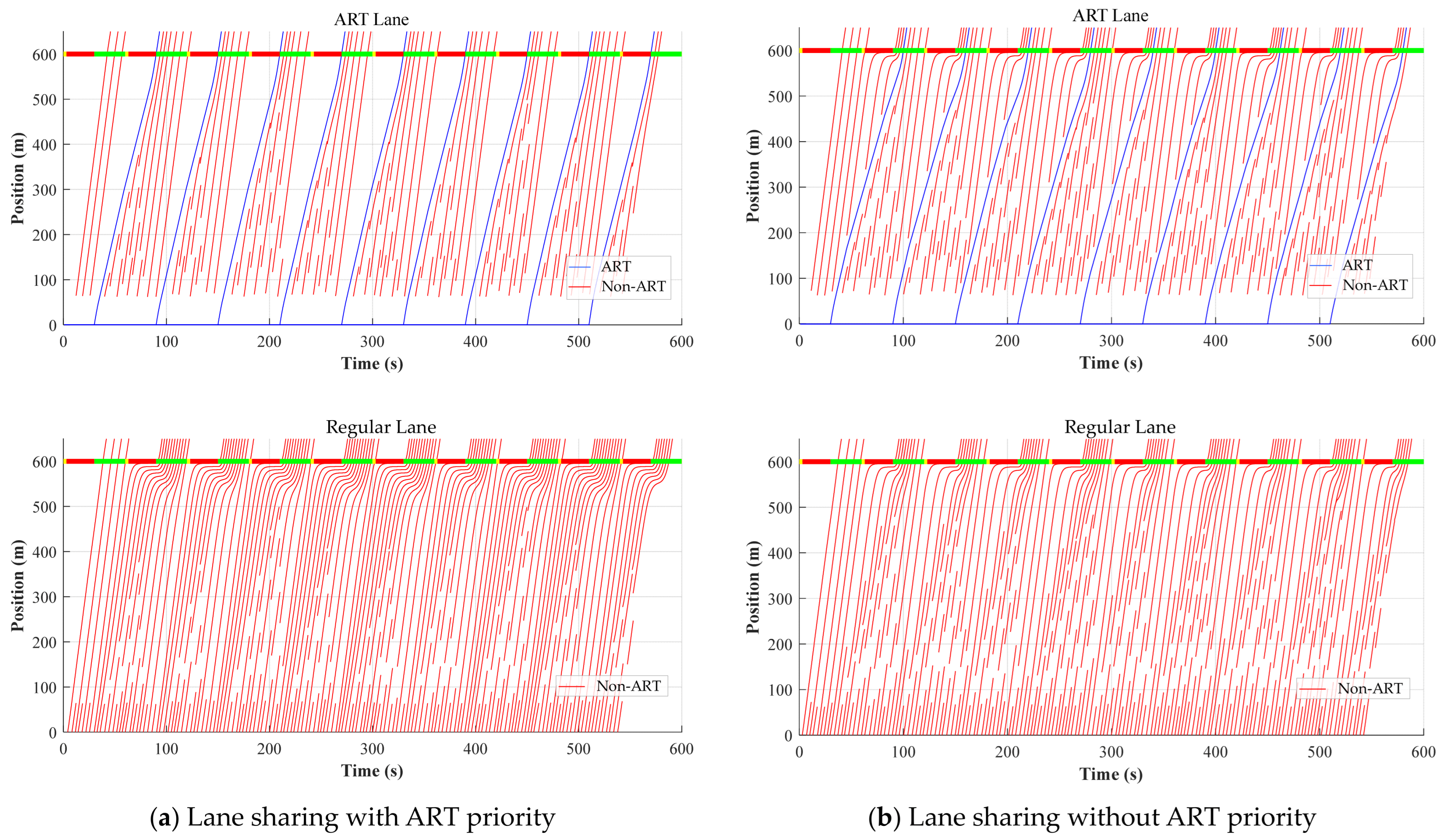

6.2. Evaluation of ART Lane-Sharing Effectiveness

6.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Traffic Demand

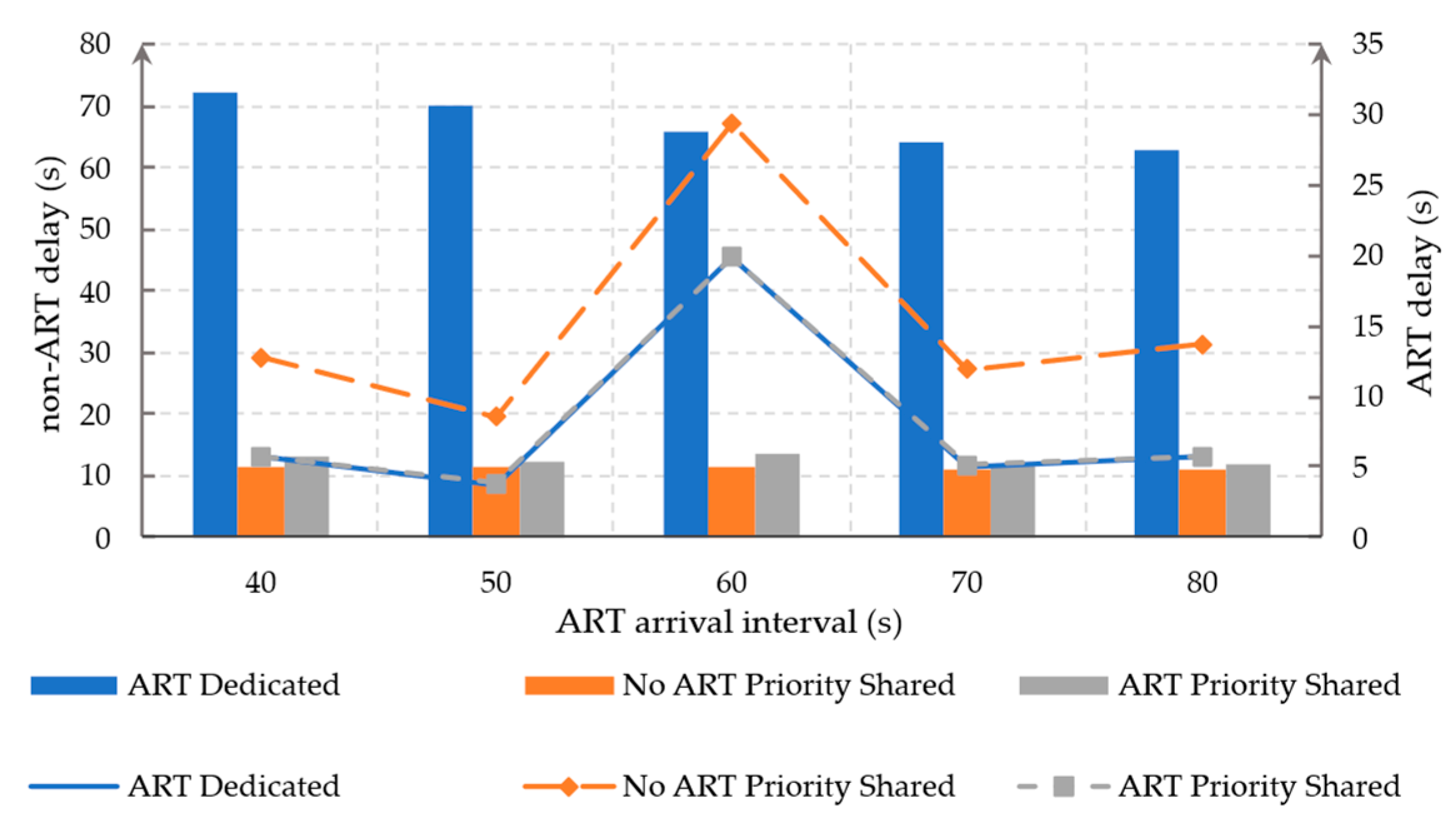

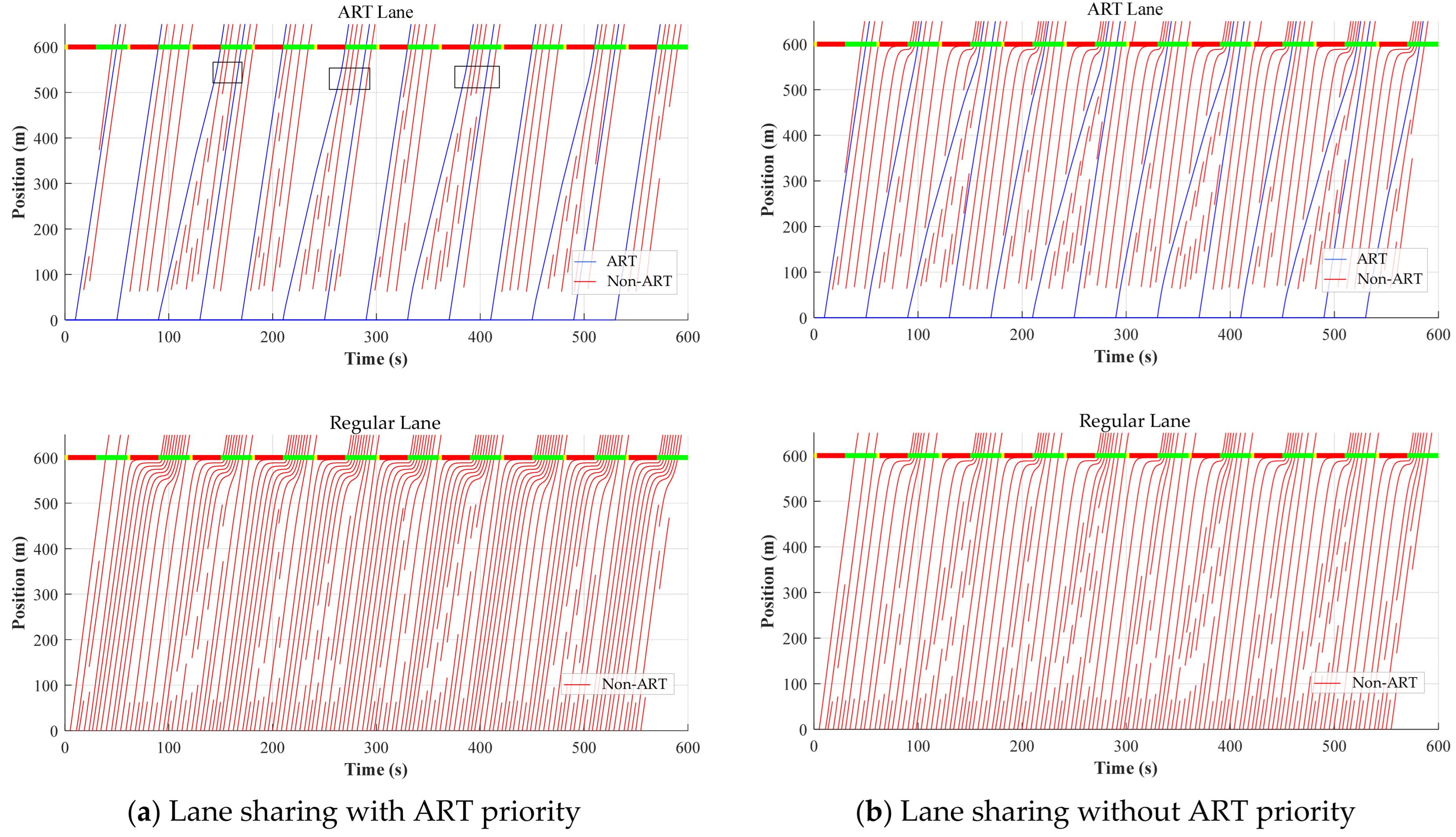

6.4. Sensitivity Analysis of ART Arrival Interval

6.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Non-ART Compliance

6.6. Computational Efficiency Analysis

7. Conclusions and Future Work

- (1)

- The proposed control framework achieves a balance between operational efficiency and the performance of non-ART vehicles, reducing the delay and energy consumption of non-ART vehicles by 72.6% and 24.6%, respectively, without increasing the delay or energy consumption of ART operations.

- (2)

- The strategy demonstrates strong adaptability under varying traffic demand levels and ART arrival intervals.

- (3)

- When the non-ART vehicles’ compliance rate with the moving block control exceeds 0.6, the operational efficiency of ART remains largely unaffected.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, J.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Huang, R.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, C. Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit Tram: System Architecture, Design and Applications. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2024, 3, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Gong, M.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, S.; Fan, J.; Xu, Z.; Hong, J. In Situ Mechanical Response Characteristics of Autonomous Rail Rapid Transit (ART) Applied to Semi-Flexible Asphalt Pavements. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2644–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Dvivedi, A.; Kumar, P. Carbon Neutrality in Transportation: In the Context of Renewable Sources. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2025, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; He, W. Is a Dedicated Bus Lane Operationally and Environmentally Beneficial? A Case Study in Beijing. Transp. Lett. 2024, 17, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Head, L.; Yan, S.; Ma, W. Development and Evaluation of Bus Lanes with Intermittent and Dynamic Priority in Connected Vehicle Environment. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 22, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Lu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lu, L.; Ding, N.; Lu, Z.; Tian, Z.; Lu, L. Optimization of Autonomous Rail Rapid Transit at Arterial-Branch Intersection: A Fuzzy Control with Borrowable Lane Approach; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, J.; Lu, B. Traffic Control System with Intermittent Bus Lanes. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1997, 30, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, V.; Baichuan, L. The Intermittent Bus Lane Signals Setting within an Area. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2000, 33, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabaut, N.; Barcet, A. Demonstration and Evaluation of an Intermittent Bus Lane Strategy. Public Transp. 2019, 11, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Lai, H. Intermittent and Dynamic Transit Lanes: Melbourne, Australia, Experience. Transp. Res. Rec. 2008, 2072, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, J.; Lu, B.; Vieira, J.; Roque, R. Demonstration of the Intermittent Bus Lane in Lisbon. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2006, 39, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, M.; Daganzo, C.F. Bus Lanes with Intermittent Priority: Strategy Formulae and an Evaluation. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2006, 40, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.-C.; Lo, H.-H.; Hsu, Y.-T.; Huang, H.-J. Exploring the Effects of Passive Transit Signal Priority Design on Bus Rapid Transit Operation: A Microsimulation-Based Optimization Approach. Transp. Lett. 2022, 14, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Sun, J.; Kan, Y.; Tian, Y. Operation of Dedicated Lanes with Intermittent Priority on Highways: Conceptual Development and Simulation Validation. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 28, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Long, J. An Eco-Driving Strategy for Partially Connected Automated Vehicles at a Signalized Intersection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 15780–15793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Borges, R.; Quaglietta, E. Assessing Hyperloop Transport Capacity Under Moving-Block and Virtual Coupling Operations. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 12612–12621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, C.; Yuwen, T.; Wan, Z.; Luo, Y. A Lightweight LiDAR-Camera Sensing Method of Obstacles Detection and Classification for Autonomous Rail Rapid Transit. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 23043–23058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Xu, C.; Ai, Q.; Ren, W.; Wang, C.; Peng, C.; Jiao, Y. Developing a Jam-Absorption Strategy for Mixed Traffic Flow at Signalized Intersections Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Transp. Lett. 2024, 17, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ran, B.; Yao, Z. Cooperative Eco-Driving for Mixed Platoons With Heterogeneous Energy at a Signalized Intersection Based on a Mixed Space-Time-State Network. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 11715–11731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yue, R.; Yang, G.; Chen, S.; Zhu, C. A Lane Usage Strategy for General Traffic Access on Bus Lanes under Partially Connected Vehicle Environment. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2025, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yang, Y. Starting from June 1st, Domestic Bus Lanes Will Shift from Dedicated to Shared Use to Improve Road Traffic Efficiency Through Refined Management. Available online: https://china.cnr.cn/gdgg/20230505/t20230505_526241165.shtml (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Xie, M.; Ramanathan, S.; Rau, A.; Eckhoff, D.; Busch, F. Design and Evaluation of V2X-Based Dynamic Bus Lanes. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 136094–136104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Dong, H.; Wang, K.; Shao, J.; Zhao, C. Setting the Intermittent Bus Approach of Intersections: A Novel Lane Multiplexing-Based Method with an Intersection Signal Coordination Model. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versluis, N.D.; Quaglietta, E.; Goverde, R.M.P.; Pellegrini, P.; Rodriguez, J. Real-Time Railway Traffic Management under Moving-Block Signalling: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 158, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesting, A.; Treiber, M.; Schönhof, M.; Helbing, D. Adaptive Cruise Control Design for Active Congestion Avoidance. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2008, 16, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, F.; Wang, S.-Q.; Qin, Y.-Z.; Zeng, M. Analyzing the Short- and Long-Term Car-Following Behavior in Multiple Factor Coupled Scenarios. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, F.; Yue, S.; Zeng, M.; He, Z.; Ngoduy, D. Platoon or Individual: An Adaptive Car-Following Control of Connected and Automated Vehicles. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 191, 115850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, X. Eco-Driving Advisory Strategies for a Platoon of Mixed Gasoline and Electric Vehicles in a Connected Vehicle System. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 63, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, C.; Ahn, K.; Rakha, H.A. Power-Based Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption Model: Model Development and Validation. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcelik, R.; Besley, M. Operating Cost, Fuel Consumption, and Emission Models in aaSIDRA and aaMOTION. In Proceedings of the 25th Conference of Australian Institutes of Transport Research (CAITR 2003), Adelaide, Australia, 3–5 December 2003; University of South Australia Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2003; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, K. Mixed Platoon Control of Automated and Human-Driven Vehicles at a Signalized Intersection: Dynamical Analysis and Optimal Control. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 127, 103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, J.; An, S.; Wang, M.; Park, B.B. Eco Approaching at an Isolated Signalized Intersection under Partially Connected and Automated Vehicles Environment. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 79, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yao, Z. Lane-Change Leading Strategy for CAV-Dedicated Lanes in Mixed Traffic Environments Considering Human Driver Randomness and Compliance. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 178, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhao, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Hu, S.; Hua, W.; Ji, W.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J. A Generic Approach to Eco-Driving of Connected Automated Vehicles in Mixed Urban Traffic and Heterogeneous Power Conditions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11963–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Trajectory Planning at a Signalized Road Section in a Mixed Traffic Environment Considering Lane-Changing of CAVs and Stochasticity of HDVs. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 158, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Yu, C.; Yang, X. Trajectory Planning for Connected and Automated Vehicles at Isolated Signalized Intersections under Mixed Traffic Environment. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 130, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Yu, D.; Luan, S.; Zhou, H.; Meng, F. Integrating Traffic Signal Optimization with Vehicle Microscopic Control to Reduce Energy Consumption in a Connected and Automated Vehicles Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, N.; Dimitrov, V. Influence of the Braking on the Comfort during Positioning of a Metro Train. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th Electrical Engineering Faculty Conference (BulEF), Varna, Bulgaria, 11–14 September 2019; IEEE: Varna, Bulgaria, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Agamawi, Y.M.; Rao, A.V. CGPOPS: A C++ Software for Solving Multiple-Phase Optimal Control Problems Using Adaptive Gaussian Quadrature Collocation and Sparse Nonlinear Programming. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2020, 46, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Bertini, R.L.; Qu, X.; Zhao, X. Trajectory Optimization for a Connected Automated Traffic Stream: Comparison Between an Exact Model and Fast Heuristics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 2969–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Vehicle Index, | |

| Space dimension index, | |

| Time dimension index, | |

| State (Velocity) dimension index, | |

| Space–time–state arc index, | |

| The cost of the vehicle traveling on the arc | |

| Starting point for vehicle | |

| The endpoint of vehicle | |

| Start time of vehicle | |

| End time of vehicle | |

| Whether vehicle passes through the space–time node | |

| Conflict region of space–time node | |

| Sets | |

| Set of all vehicles | |

| Space set | |

| Time set | |

| State set | |

| Space–time–state arcs set | |

| Variables | |

| , if vehicle selects the space–time–state arcs ; otherwise. |

| Parameter | Definition | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Electric vehicle efficiency | 92%, 91%, 90% | |

| Regenerative efficiency parameter | 0.0411 | |

| Vehicle mass | ART: 30,000 ; non-ART: 1600 | |

| Air density | 1.2256 | |

| Aerodynamic drag coefficient | ART: 0.75; non-ART: 0.28 | |

| Frontal area of the vehicle | ART:8.30 ; non-ART: 2.34 | |

| , , | Rolling resistance coefficients | ART: 2.1, 0.042, 6.2; non-ART: 1.75, 0.0328, 4.575 |

| Idle fuel consumption rate | 0.375 | |

| , | Efficiency constants | 0.09, ) |

| Gravitational acceleration | 9.8 |

| Category | Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal | Cycle length | 60 s | |

| Green time | - | 30 s | |

| Vehicles | Traffic volume | 780 veh/h/ln | |

| ART arrival interval (headway) | - | 60 s | |

| Desired speed (non-ART vehicles) | 18 m/s | ||

| Desired headway (non-ART vehicles) | - | 2 s | |

| Desired speed (ART) | 15 m/s | ||

| Vehicle length (non-ART vehicles) | 5 m | ||

| Vehicle length (ART) | 31.64 m | ||

| Max acceleration | 2 m/s2 | ||

| Max deceleration (all vehicles) | −3 m/s2 | ||

| Comfortable deceleration (ART) | −1.5 m/s2 | ||

| Braking delay (ART) | 1 s | ||

| Minimum standstill safety distance | 5 m | ||

| Simulation | Time step | - | 1 s |

| Simulation duration | - | 600 s |

| Indicator | GPOPS | Segmentation Method | This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy consumption (kWh) | 1.32 | 1.52 | 1.26 |

| Computation time (s) | 0.15 | 0.56 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Xiao, G.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z. Moving-Block-Based Lane-Sharing Strategy for Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit with a Leading Eco-Driving Approach. Mathematics 2026, 14, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010126

Zhang J, Xiao G, Xu J, Zhang S, Jiang Y, Yao Z. Moving-Block-Based Lane-Sharing Strategy for Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit with a Leading Eco-Driving Approach. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Junlin, Guosheng Xiao, Jianping Xu, Shiliang Zhang, Yangsheng Jiang, and Zhihong Yao. 2026. "Moving-Block-Based Lane-Sharing Strategy for Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit with a Leading Eco-Driving Approach" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010126

APA StyleZhang, J., Xiao, G., Xu, J., Zhang, S., Jiang, Y., & Yao, Z. (2026). Moving-Block-Based Lane-Sharing Strategy for Autonomous-Rail Rapid Transit with a Leading Eco-Driving Approach. Mathematics, 14(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010126