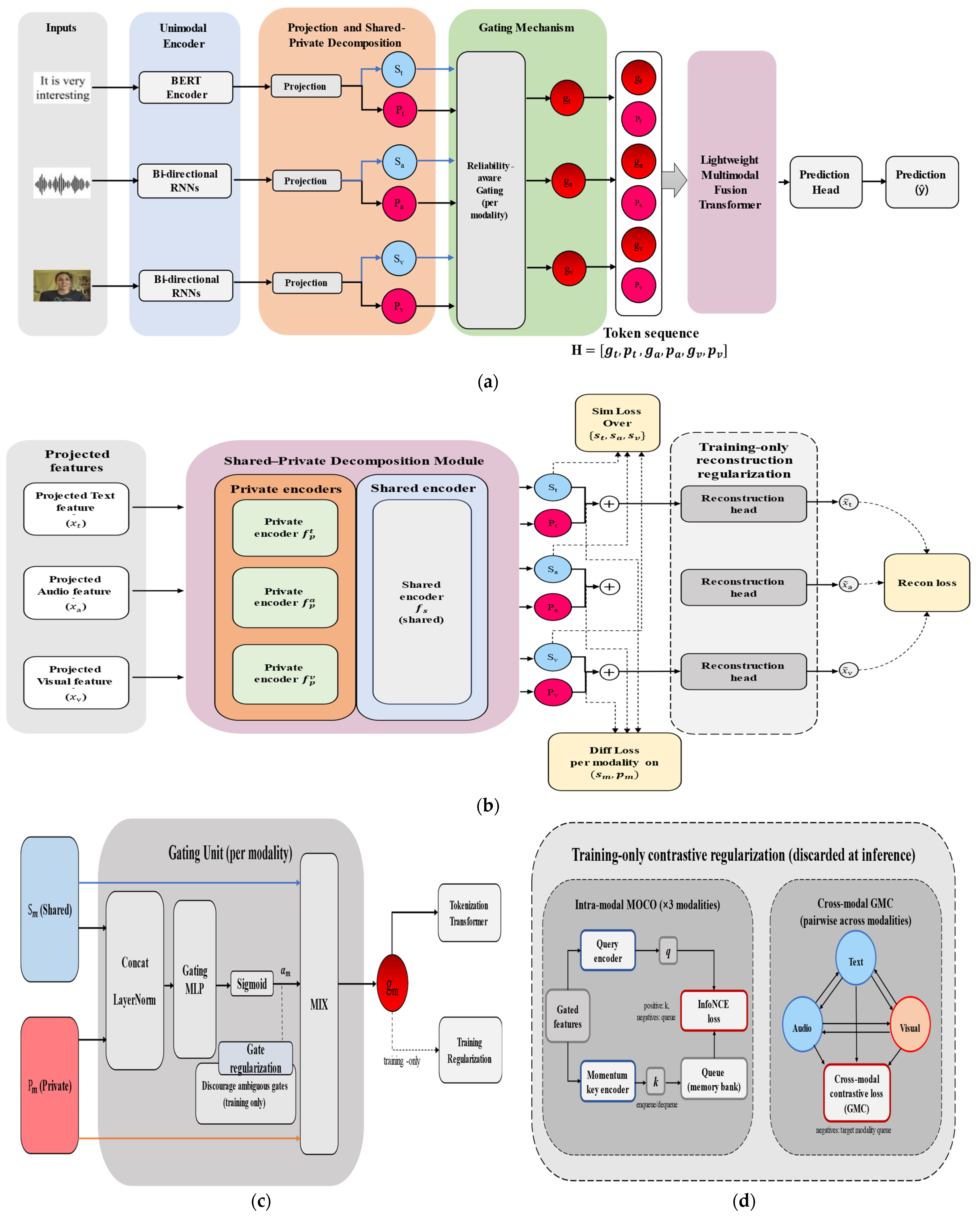

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed MISA-GMC framework. (a) Inference-time pipeline. For each modality , the input sequence is encoded and decomposed into a shared representation and a private representation . A reliability-aware gating mechanism produces a scalar gate to adaptively mix shared and private information, yielding a fused modality feature . The fused features from all modalities are then tokenized and fed into a lightweight Transformer-based fusion/prediction head to output the final sentiment prediction. (b) Shared–private decomposition and reconstruction regularization. The shared/private factors are learned with auxiliary training objectives (e.g., reconstruction and consistency constraints) to encourage informative shared factors while preserving modality-specific private factors, thereby reducing redundancy and promoting disentanglement. (c) Gating unit (per modality). The gate is computed by concatenating and , followed by LayerNorm and a small MLP with a sigmoid activation to obtain . A gate regularization term is applied during training to discourage ambiguous gates and stabilize the reliability estimation. The mixed output is denoted as . (d) Training-only contrastive regularization (discarded at inference). Two complementary contrastive branches are introduced to improve representation quality: (i) Intra-modal MoCo for each modality, implemented with a query encoder, a momentum-updated key encoder, a memory queue, and an InfoNCE loss; and (ii) Cross-modal GMC that performs pairwise contrastive learning across modalities (Text–Audio–Visual) to strengthen modality correlation modeling. These contrastive branches (including momentum encoders and queues) are used only in training and are removed at inference, so the deployment-time computation follows only the concise pipeline in (a).

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed MISA-GMC framework. (a) Inference-time pipeline. For each modality , the input sequence is encoded and decomposed into a shared representation and a private representation . A reliability-aware gating mechanism produces a scalar gate to adaptively mix shared and private information, yielding a fused modality feature . The fused features from all modalities are then tokenized and fed into a lightweight Transformer-based fusion/prediction head to output the final sentiment prediction. (b) Shared–private decomposition and reconstruction regularization. The shared/private factors are learned with auxiliary training objectives (e.g., reconstruction and consistency constraints) to encourage informative shared factors while preserving modality-specific private factors, thereby reducing redundancy and promoting disentanglement. (c) Gating unit (per modality). The gate is computed by concatenating and , followed by LayerNorm and a small MLP with a sigmoid activation to obtain . A gate regularization term is applied during training to discourage ambiguous gates and stabilize the reliability estimation. The mixed output is denoted as . (d) Training-only contrastive regularization (discarded at inference). Two complementary contrastive branches are introduced to improve representation quality: (i) Intra-modal MoCo for each modality, implemented with a query encoder, a momentum-updated key encoder, a memory queue, and an InfoNCE loss; and (ii) Cross-modal GMC that performs pairwise contrastive learning across modalities (Text–Audio–Visual) to strengthen modality correlation modeling. These contrastive branches (including momentum encoders and queues) are used only in training and are removed at inference, so the deployment-time computation follows only the concise pipeline in (a).

![Mathematics 14 00115 g001 Mathematics 14 00115 g001]()

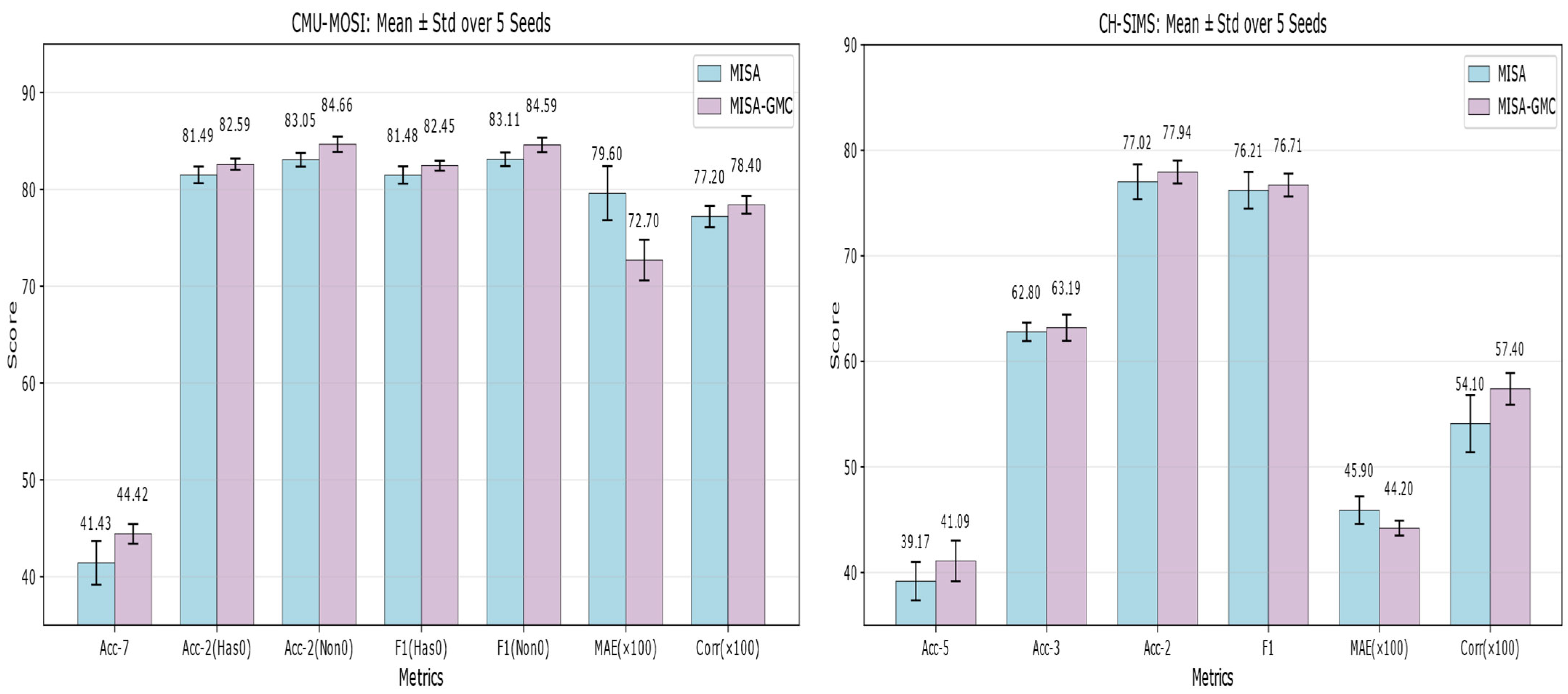

Figure 2.

Mean ± Std over five pre-defined seeds on CMU-MOSI and CH-SIMS. Bars denote the mean performance across five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111}, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. MAE and Corr are scaled by 100 for visualization.

Figure 2.

Mean ± Std over five pre-defined seeds on CMU-MOSI and CH-SIMS. Bars denote the mean performance across five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111}, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. MAE and Corr are scaled by 100 for visualization.

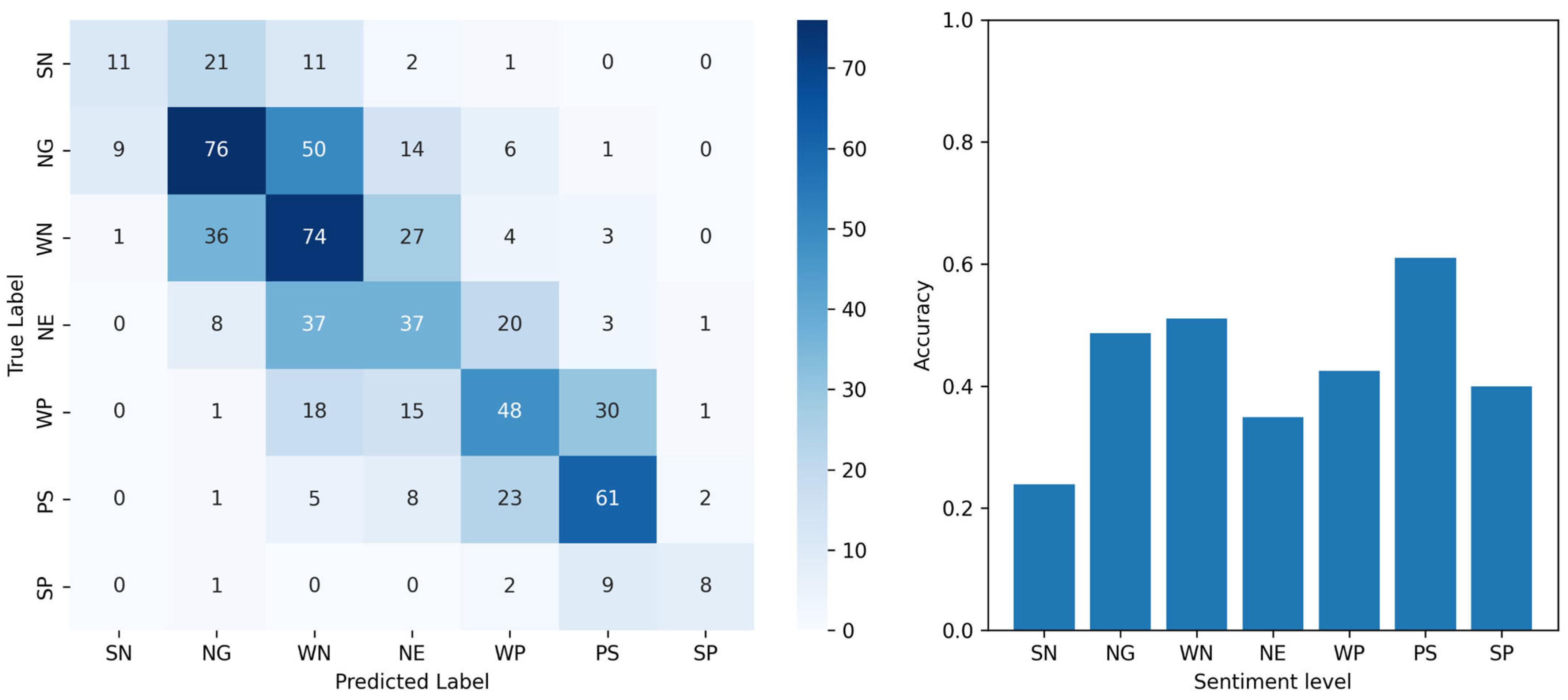

Figure 3.

Performance analysis of MISA-GMC on the CMU-MOSI test set. (Left) The 7-class confusion matrix. (Right) Per-category classification accuracy. The sentiment labels are abbreviated as follows: SN (Strong Negative), NG (Negative), WN (Weak Negative), NE (Neutral), WP (Weak Positive), PS (Positive), and SP (Strong Positive).

Figure 3.

Performance analysis of MISA-GMC on the CMU-MOSI test set. (Left) The 7-class confusion matrix. (Right) Per-category classification accuracy. The sentiment labels are abbreviated as follows: SN (Strong Negative), NG (Negative), WN (Weak Negative), NE (Neutral), WP (Weak Positive), PS (Positive), and SP (Strong Positive).

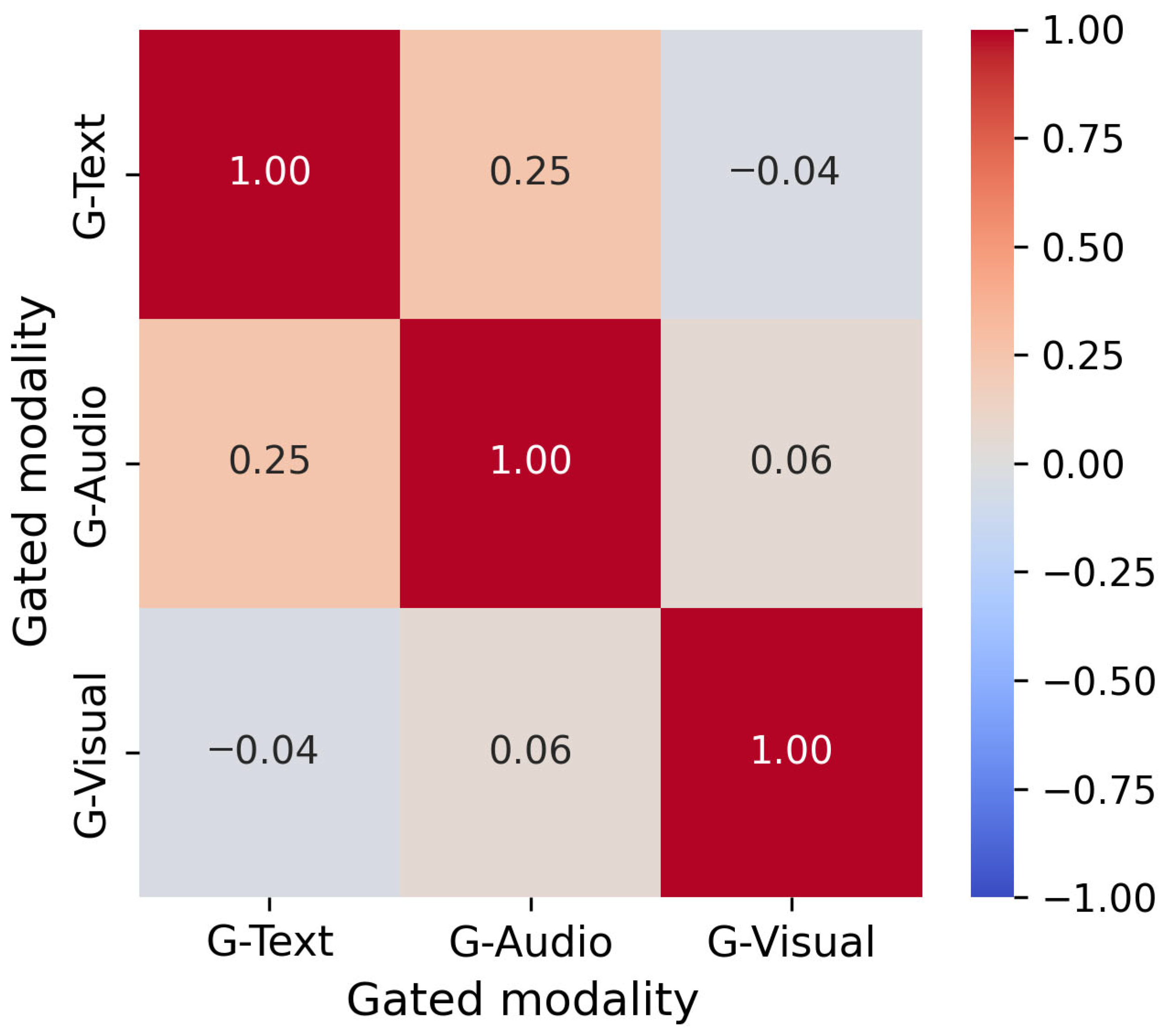

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmap of gated modality representations of MISA-GMC on the CMU-MOSI test set. The matrix shows the average pairwise correlations among G-Text, G-Audio, and G-Visual. Here, G-Text, G-Audio, and G-Visual denote the gated representations of the text, audio, and visual modalities, respectively.

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmap of gated modality representations of MISA-GMC on the CMU-MOSI test set. The matrix shows the average pairwise correlations among G-Text, G-Audio, and G-Visual. Here, G-Text, G-Audio, and G-Visual denote the gated representations of the text, audio, and visual modalities, respectively.

Figure 5.

Visualization of ablation results on the CMU-MOSI and CH-SIMS datasets. The (left) panel shows the results on the CMU-MOSI dataset, and the (right) panel shows the results on the CH-SIMS dataset. The bar charts compare the performance of different model variants (MISA, MISA + GATE, MISA + MOCO, MISA + MOCO + GATE, and MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC) under multiple evaluation metrics. Although adding Gating or MoCo alone generally improves performance, their simple combination leads to fluctuations on some metrics; after further introducing the GMC module, the final MISA-GMC model (MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC) achieves the most stable and comprehensive improvements.

Figure 5.

Visualization of ablation results on the CMU-MOSI and CH-SIMS datasets. The (left) panel shows the results on the CMU-MOSI dataset, and the (right) panel shows the results on the CH-SIMS dataset. The bar charts compare the performance of different model variants (MISA, MISA + GATE, MISA + MOCO, MISA + MOCO + GATE, and MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC) under multiple evaluation metrics. Although adding Gating or MoCo alone generally improves performance, their simple combination leads to fluctuations on some metrics; after further introducing the GMC module, the final MISA-GMC model (MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC) achieves the most stable and comprehensive improvements.

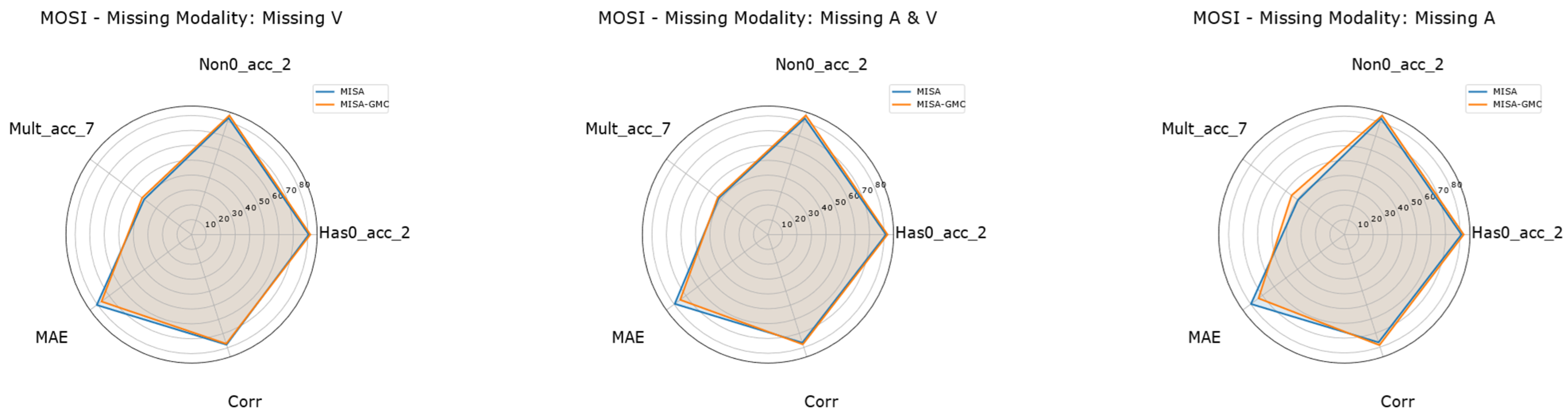

Figure 6.

Radar plots of MISA vs. MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI under different missing-modality settings. The three radar plots visualize the key metrics (Non0-Acc-2, Mult-Acc-7, MAE, and Corr) of MISA (blue) and MISA-GMC (orange) on CMU-MOSI. From left to right, the panels correspond to Missing V (T+A), Missing A (T+V), and Missing A & V (T).

Figure 6.

Radar plots of MISA vs. MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI under different missing-modality settings. The three radar plots visualize the key metrics (Non0-Acc-2, Mult-Acc-7, MAE, and Corr) of MISA (blue) and MISA-GMC (orange) on CMU-MOSI. From left to right, the panels correspond to Missing V (T+A), Missing A (T+V), and Missing A & V (T).

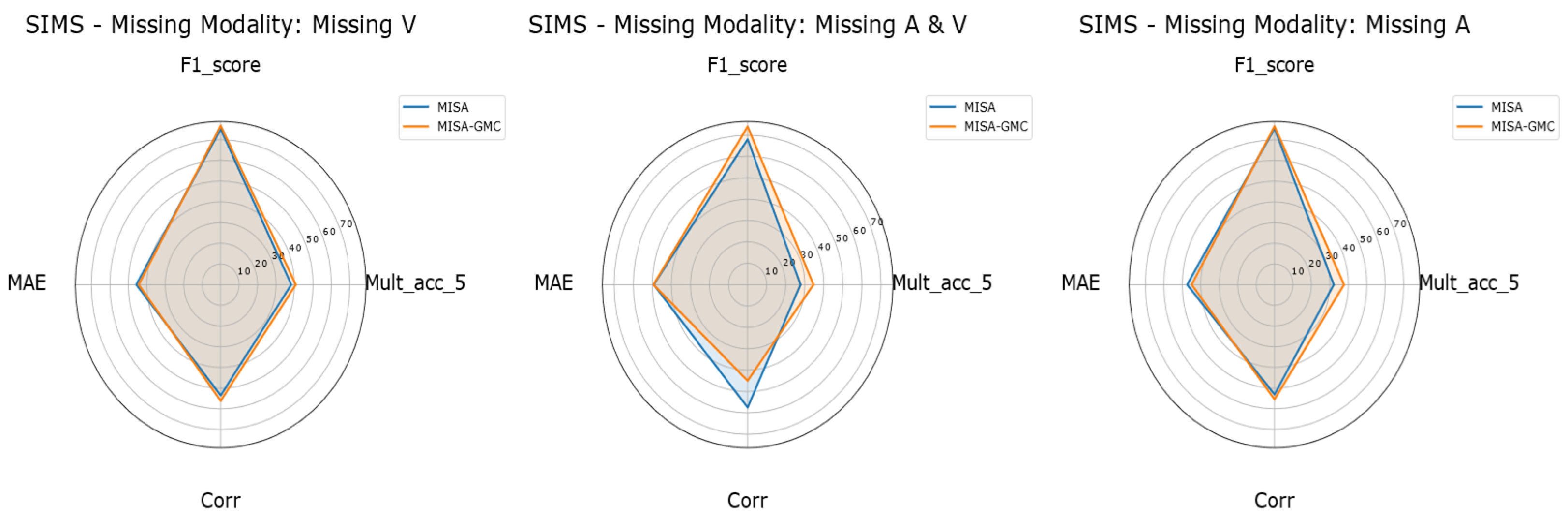

Figure 7.

Radar plots of MISA vs. MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS under different missing-modality settings. The three radar plots visualize the key metrics (F1, Mult-Acc-5, MAE, and Corr) of MISA (blue) and MISA-GMC (orange) on the CH-SIMS dataset. From left to right, the panels correspond to Missing V (T+A), Missing A (T+V), and Missing A & V (T).

Figure 7.

Radar plots of MISA vs. MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS under different missing-modality settings. The three radar plots visualize the key metrics (F1, Mult-Acc-5, MAE, and Corr) of MISA (blue) and MISA-GMC (orange) on the CH-SIMS dataset. From left to right, the panels correspond to Missing V (T+A), Missing A (T+V), and Missing A & V (T).

Table 1.

Partitioning of the training, validation, and test sets of different datasets.

Table 1.

Partitioning of the training, validation, and test sets of different datasets.

| Datasets | Train | Valid | Test | Total | Language |

|---|

| CMU-MOSEI | 16,326 | 1871 | 4659 | 22,856 | English |

| CMU-MOSI | 1284 | 229 | 686 | 2199 | English |

| CH-SIMS | 1368 | 456 | 457 | 2281 | Chinese |

Table 2.

Key hyper-parameters of MISA-GMC on different datasets.

Table 2.

Key hyper-parameters of MISA-GMC on different datasets.

| Parameter | CMU-MOSI | CMU-MOSEI | CH-SIMS |

|---|

| Batch size | 16 | 64 | 64 |

| Dropout | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 0.3 | 0.8 | 1 |

| Gating temperature | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Gate strength (range) | [0.3, 0.7] | [0.3, 0.7] | [0.3, 0.7] |

| (range) | [0.05, 0.12] | [0.05, 0.12] | [0.05, 0.12] |

| range) | [0, 0.05] | [0, 0.05] | [0.02, 0.05] |

| 4096 | 4096 | 4096 |

| 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 256 | 256 | 256 |

Table 3.

The experimental results of the model on CMU-MOSI. Boldface indicates the best results: The bolded “Ours” highlights the proposed model and indicates the best-performing results among all compared methods. Boldface is used to visually emphasize the superiority of our model compared with classical baselines such as TFN, MulT, and CENet. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 3.

The experimental results of the model on CMU-MOSI. Boldface indicates the best results: The bolded “Ours” highlights the proposed model and indicates the best-performing results among all compared methods. Boldface is used to visually emphasize the superiority of our model compared with classical baselines such as TFN, MulT, and CENet. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | CMU-MOSI |

|---|

| Acc-7↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| TFN | 37.17 | 78.57/80.03 | 78.35/79.88 | 0.915 | 0.662 |

| MulT | 33.24 | 79.30/81.10 | 79.14/81.01 | 0.932 | 0.676 |

| LMF | 31.05 | 77.99/79.12 | 78.04/79.24 | 1.006 | 0.678 |

| CENet | 43 | 82.36/83.84 | 82.35/83.88 | 0.747 | 0.794 |

| MMIM | 45.04 | 82.65/84.45 | 82.63/84.48 | 0.741 | 0.794 |

| Self-MM | 42.13 | 83.53/85.06 | 83.51/85.09 | 0.753 | 0.795 |

| ALMT | 42.27 | 81.78/82.93 | 81.83/83.03 | 0.765 | 0.79 |

| TETFN | 44.75 | 82.51/84.30 | 82.45/84.29 | 0.728 | 0.788 |

| MISA | 43.29 | 81.34/83.08 | 81.28/83.08 | 0.785 | 0.764 |

| Ours | 45.92 | 82.94/85.21 | 82.75/85.10 | 0.712 | 0.795 |

Table 4.

The experimental results of the model on CMU-MOSEI. Boldface indicates the best results: The bolded “Ours” highlights the proposed model and indicates the best-performing results among all compared methods. Boldface is used to visually emphasize the superiority of our model compared with classical baselines such as TFN, MulT, and CENet. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 4.

The experimental results of the model on CMU-MOSEI. Boldface indicates the best results: The bolded “Ours” highlights the proposed model and indicates the best-performing results among all compared methods. Boldface is used to visually emphasize the superiority of our model compared with classical baselines such as TFN, MulT, and CENet. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | CMU-MOSEI |

|---|

| Acc-7↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| TFN | 51.68 | 82.23/81.81 | 81.95/81.24 | 0.58 | 0.709 |

| MulT | 50.35 | 82.79/83.71 | 82.69/83.28 | 0.581 | 0.724 |

| LMF | 53.27 | 82.08/84.62 | 82.43/84.53 | 0.553 | 0.739 |

| CENet | 52.52 | 83.17/86.02 | 83.49/85.93 | 0.549 | 0.772 |

| MMIM | 50.03 | 83.32/83.30 | 83.12/82.83 | 0.58 | 0.733 |

| Self-MM | 50.38 | 84.89/85.94 | 84.97/85.76 | 0.572 | 0.767 |

| ALMT | 50.53 | 84.07/85.61 | 84.08/85.31 | 0.557 | 0.767 |

| MISA | 49.26 | 83.24/85.03 | 83.43/84.87 | 0.585 | 0.76 |

| Ours | 51.62 | 84.18/85.50 | 84.25/85.27 | 0.56 | 0.756 |

Table 5.

The experimental results of the model on CH-SIMS. Boldface indicates the proposed model (Ours). Acc-2, Acc-3, and Acc-5 denote binary, three-class, and five-class accuracies, respectively. F1 is the F1 score, and MAE↓ is the mean absolute error, where ↓ means that lower values are better. Corr↑ denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, where higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 5.

The experimental results of the model on CH-SIMS. Boldface indicates the proposed model (Ours). Acc-2, Acc-3, and Acc-5 denote binary, three-class, and five-class accuracies, respectively. F1 is the F1 score, and MAE↓ is the mean absolute error, where ↓ means that lower values are better. Corr↑ denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, where higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | CH-SIMS |

|---|

| Acc-5↑ | Acc-3↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| TFN | 40.48 | 64.33 | 77.46 | 75.7 | 0.44 | 0.589 |

| MulT | 39.17 | 64.11 | 78.12 | 77.93 | 0.446 | 0.586 |

| LMF | 41.36 | 68.05 | 78.56 | 78.33 | 0.438 | 0.591 |

| CENet | 21.01 | 42.89 | 66.74 | 60.48 | 0.586 | 0.088 |

| MMIM | 37.2 | 60.83 | 75.93 | 75.44 | 0.472 | 0.497 |

| Self-MM | 42.23 | 67.61 | 78.99 | 78.56 | 0.415 | 0.6 |

| ALMT | 39.82 | 64.99 | 78.99 | 78.45 | 0.445 | 0.559 |

| MTFN | 40.7 | 65.21 | 78.56 | 78.06 | 0.464 | 0.549 |

| MLMF | 31.07 | 65.43 | 80.53 | 80.58 | 0.432 | 0.643 |

| TETFN | 39.39 | 64.99 | 79.21 | 78.96 | 0.427 | 0.593 |

| MISA | 41.14 | 63.89 | 76.59 | 76.01 | 0.458 | 0.552 |

| Ours | 42.67 | 64.11 | 78.34 | 77.56 | 0.437 | 0.571 |

Table 6.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI over five pre-defined seeds (mean ± Std). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111} under identical settings. Acc-2/F1 are shown for both Has0 and Non0 protocols, where Non0 excludes neutral samples. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 6.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI over five pre-defined seeds (mean ± Std). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111} under identical settings. Acc-2/F1 are shown for both Has0 and Non0 protocols, where Non0 excludes neutral samples. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | Acc-7↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 41.43 ± 2.25 | 81.49 ± 0.86/83.05 ± 0.71 | 81.48 ± 0.89/83.11 ± 0.71 | 0.796 ± 0.028 | 0.772 ± 0.011 |

| MISA-GMC | 44.42 ± 1.02 | 82.59 ± 0.58/84.66 ± 0.79 | 82.45 ± 0.51/84.59 ± 0.74 | 0.727 ± 0.021 | 0.784 ± 0.009 |

Table 7.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS over five pre-defined seeds (mean ± Std). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111} using the same training and evaluation setup. MAE is lower-is-better, while accuracy/F1/Corr are higher-is-better. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 7.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS over five pre-defined seeds (mean ± Std). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five runs with seeds {1,11,111,1111,11111} using the same training and evaluation setup. MAE is lower-is-better, while accuracy/F1/Corr are higher-is-better. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | Acc-5↑ | Acc-3↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 39.17 ± 1.83 | 62.80 ± 0.87 | 77.02 ± 1.65 | 76.21 ± 1.74 | 0.459 ± 0.013 | 0.541 ± 0.027 |

| MISA-GMC | 41.09 ± 1.94 | 63.79 ± 1.24 | 77.94 ± 1.08 | 76.81 ± 1.08 | 0.442 ± 0.007 | 0.574 ± 0.015 |

Table 8.

Ablation study on the CMU-MOSI. This table reports the incremental performance gains of each component added to the MISA baseline, including the Gating module, MoCo contrastive learning, and the proposed GMC correlation modeling. The final configuration MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC represents our full model (MISA-GMC). Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 8.

Ablation study on the CMU-MOSI. This table reports the incremental performance gains of each component added to the MISA baseline, including the Gating module, MoCo contrastive learning, and the proposed GMC correlation modeling. The final configuration MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC represents our full model (MISA-GMC). Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | Acc-7↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 43.29 | 81.34/83.08 | 81.28/83.08 | 0.785 | 0.764 |

| MISA + GATE | 43.88 | 82.22/83.84 | 82.16/83.84 | 0.744 | 0.787 |

| MISA + MOCO | 43.59 | 81.63/84.30 | 81.50/84.26 | 0.752 | 0.779 |

| MISA + MOCO + GATE | 40.96 | 83.38/85.67 | 83.18/85.56 | 0.751 | 0.778 |

| MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC | 45.92 | 82.94/85.21 | 82.75/85.10 | 0.712 | 0.795 |

Table 9.

Ablation study on the CH-SIMS. This table reports the incremental performance gains of each component added to the MISA baseline, including the Gating module, MOCO contrastive learning, and the proposed GMC correlation modeling. The final configuration MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC represents our full model (MISA-GMC). Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 9.

Ablation study on the CH-SIMS. This table reports the incremental performance gains of each component added to the MISA baseline, including the Gating module, MOCO contrastive learning, and the proposed GMC correlation modeling. The final configuration MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC represents our full model (MISA-GMC). Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | Acc-5↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 41.14 | 76.59 | 76.01 | 0.458 | 0.552 |

| MISA + GATE | 39.82 | 77.02 | 76.64 | 0.442 | 0.560 |

| MISA + MOCO | 40.04 | 77.68 | 77.54 | 0.439 | 0.553 |

| MISA + MOCO + GATE | 38.73 | 77.24 | 76.89 | 0.449 | 0.534 |

| MISA + MOCO + GATE + GMC | 42.67 | 78.34 | 77.56 | 0.437 | 0.571 |

Table 10.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI under missing-modality settings. The table reports 7-class accuracy (Acc-7), binary accuracy (Acc-2, Has0/Non0), binary F1 (Has0/Non0), mean absolute error (MAE), and correlation (Corr) of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI. “T+A”, “T+V”, and “T” denote the cases where the visual, acoustic, and both acoustic and visual modalities are removed, respectively. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better.

Table 10.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI under missing-modality settings. The table reports 7-class accuracy (Acc-7), binary accuracy (Acc-2, Has0/Non0), binary F1 (Has0/Non0), mean absolute error (MAE), and correlation (Corr) of MISA and MISA-GMC on CMU-MOSI. “T+A”, “T+V”, and “T” denote the cases where the visual, acoustic, and both acoustic and visual modalities are removed, respectively. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better.

| Methods | CMU-MOSI |

|---|

| Acc-7↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 43.29 | 81.34/83.08 | 81.28/83.08 | 0.785 | 0.764 |

| T+A | 40.27 | 80.59/82.38 | 80.52/82.39 | 0.805 | 0.778 |

| T+V | 39.65 | 80.99/82.50 | 80.95/82.52 | 0.798 | 0.766 |

| T | 41.84 | 81.34/82.32 | 81.39/82.42 | 0.794 | 0.766 |

| MISA-GMC | 45.92 | 82.94/85.21 | 82.75/85.10 | 0.712 | 0.795 |

| T+A | 41.98 | 81.63/84.15 | 81.48/84.08 | 0.765 | 0.771 |

| T+V | 45.04 | 82.51/84.60 | 82.37/84.54 | 0.733 | 0.786 |

| T | 42.71 | 82.36/84.45 | 82.21/84.37 | 0.748 | 0.778 |

Table 11.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS under missing-modality settings. This table reports 5-class accuracy (Acc-5), 3-class accuracy (Acc-3), binary accuracy (Acc-2), F1, mean absolute error (MAE), and correlation (Corr) of MISA and MISA-GMC on the CH-SIMS dataset. “T+A”, “T+V”, and “T” denote the cases where the visual, acoustic, and both acoustic and visual modalities are removed, respectively. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better.

Table 11.

Robustness of MISA and MISA-GMC on CH-SIMS under missing-modality settings. This table reports 5-class accuracy (Acc-5), 3-class accuracy (Acc-3), binary accuracy (Acc-2), F1, mean absolute error (MAE), and correlation (Corr) of MISA and MISA-GMC on the CH-SIMS dataset. “T+A”, “T+V”, and “T” denote the cases where the visual, acoustic, and both acoustic and visual modalities are removed, respectively. Metrics marked with ↓ indicate that lower values are better, whereas metrics marked with ↑ indicate that higher values are better.

| Methods | CH-SIMS |

|---|

| Acc-5↑ | Acc-3↑ | Acc-2↑ | F1↑ | MAE↓ | Corr↑ |

|---|

| MISA | 41.14 | 63.89 | 76.59 | 76.01 | 0.458 | 0.552 |

| T+A | 38.25 | 61.84 | 74.62 | 75.06 | 0.457 | 0.535 |

| T+V | 32.12 | 61.97 | 74.88 | 75.46 | 0.474 | 0.531 |

| T | 27.79 | 60.61 | 66.74 | 68.04 | 0.493 | 0.574 |

| MISA-GMC | 42.67 | 64.11 | 78.34 | 77.56 | 0.437 | 0.571 |

| T+A | 40.7 | 64.55 | 77.02 | 76.8 | 0.444 | 0.561 |

| T+V | 37.64 | 61.71 | 77.02 | 76.58 | 0.449 | 0.555 |

| T | 34.57 | 59.08 | 74.62 | 73.96 | 0.494 | 0.45 |

Table 12.

Computational efficiency and resource usage comparison on CMU-MOSI (batch size = 64). This table shows the average training time per epoch, peak GPU memory during training and inference (reported as CUDA reserved memory), inference latency (milliseconds per batch), and throughput (samples per second) measured using forward-pass-only timing, as well as FP32 weight size and checkpoint size. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

Table 12.

Computational efficiency and resource usage comparison on CMU-MOSI (batch size = 64). This table shows the average training time per epoch, peak GPU memory during training and inference (reported as CUDA reserved memory), inference latency (milliseconds per batch), and throughput (samples per second) measured using forward-pass-only timing, as well as FP32 weight size and checkpoint size. We boldfaced the results of MISA-GMC (Ours) to facilitate readability and comparison.

| Model | Time/Epoch (s) | Train Peak (GB) | Infer Peak (GB) | Infer Latency (ms/Batch) | Infer Throughput (Samples/s) | Weights (MB) | Ckpt (MB) |

|---|

| CENet | 2.9 | 5.32 | 5.3223 | 31.60 | 1971 | 464 | 417 |

| MMIM | 6.5 | 3.77 | 3.7676 | 42.93 | 1452 | 439 | 418 |

| Self-MM | 3.1 | 4.07 | 4.0703 | 35.03 | 1780 | 410 | 391 |

| ALMT | 3.7 | 6.99 | 6.9941 | 43.04 | 1450 | 448 | 427 |

| MISA | 3.4 | 4.18 | 4.1816 | 39.14 | 1529 | 442 | 422 |

| Ours | 4.1 | 4.26 | 4.2636 | 48.18 | 1295 | 443 | 435 |