Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Selection and Location

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Problem Statement and Gap

1.3. Motivation

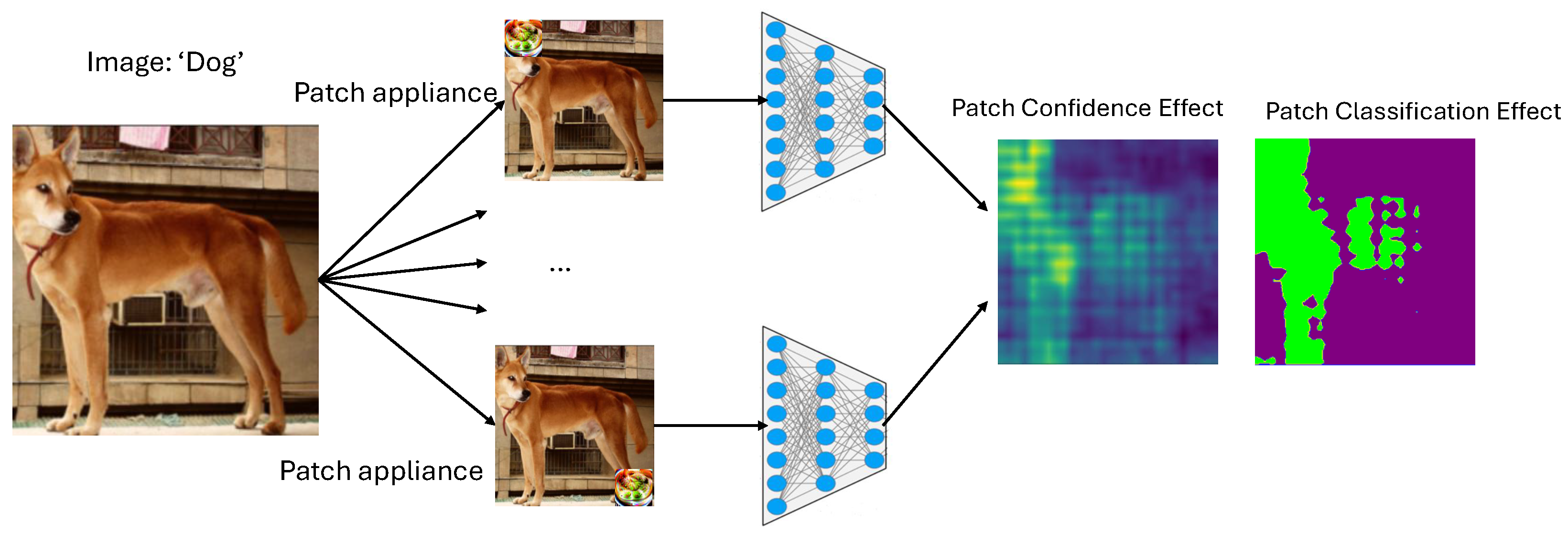

1.4. PatchMap

1.5. Contributions

- PatchMap dataset. A public release of 100 M+ location-conditioned predictions at https://huggingface.co/datasets/PatchMap/PatchMap_v1 (accessed on 15 May 2025), scaling to 6.5 B entries.

- Rigorous analysis. Unified definitions of attack-success rate (ASR) and confidence drop (), evaluated across location, patch size, and model robustness, exposing recurring spatial vulnerabilities.

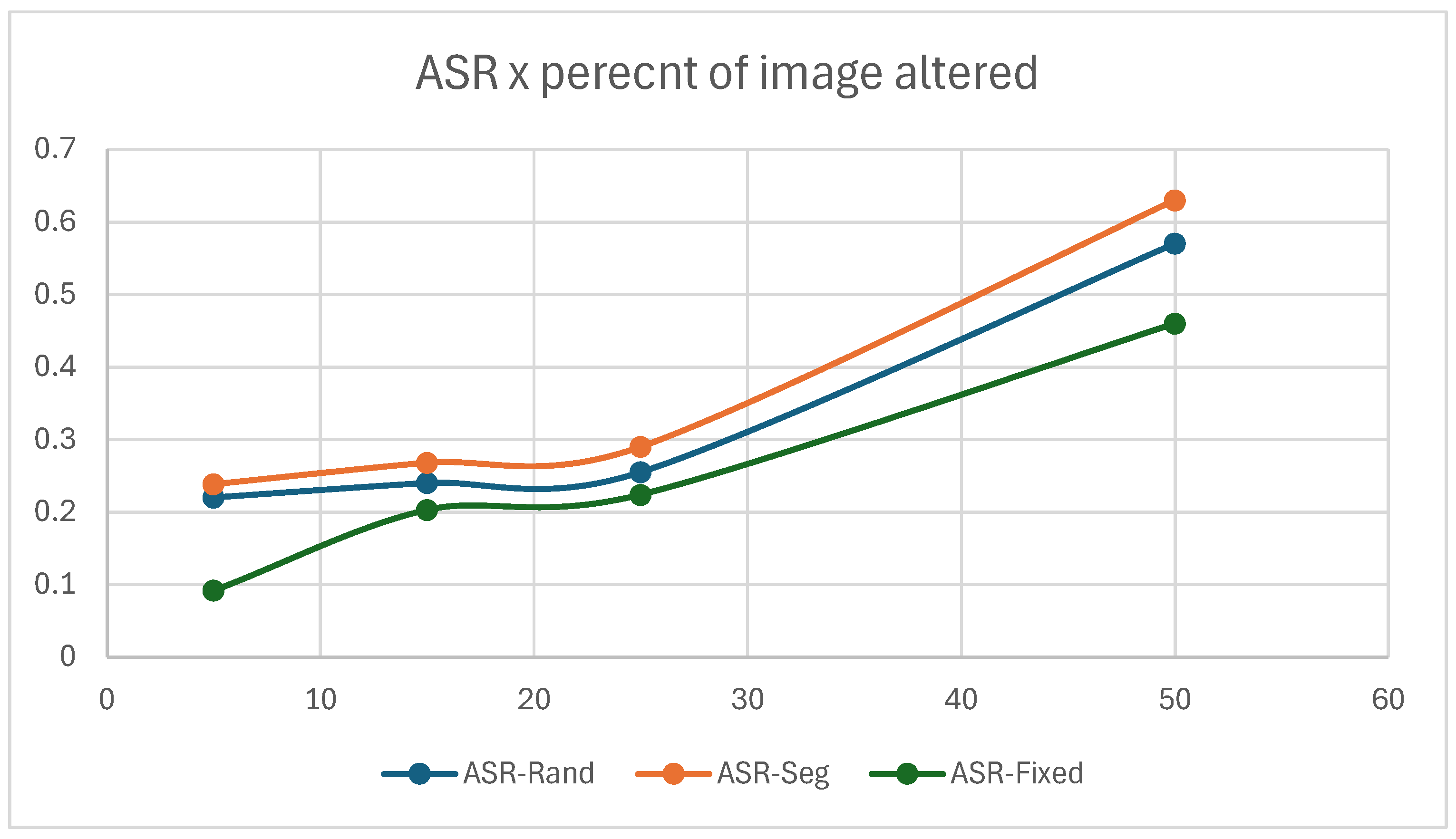

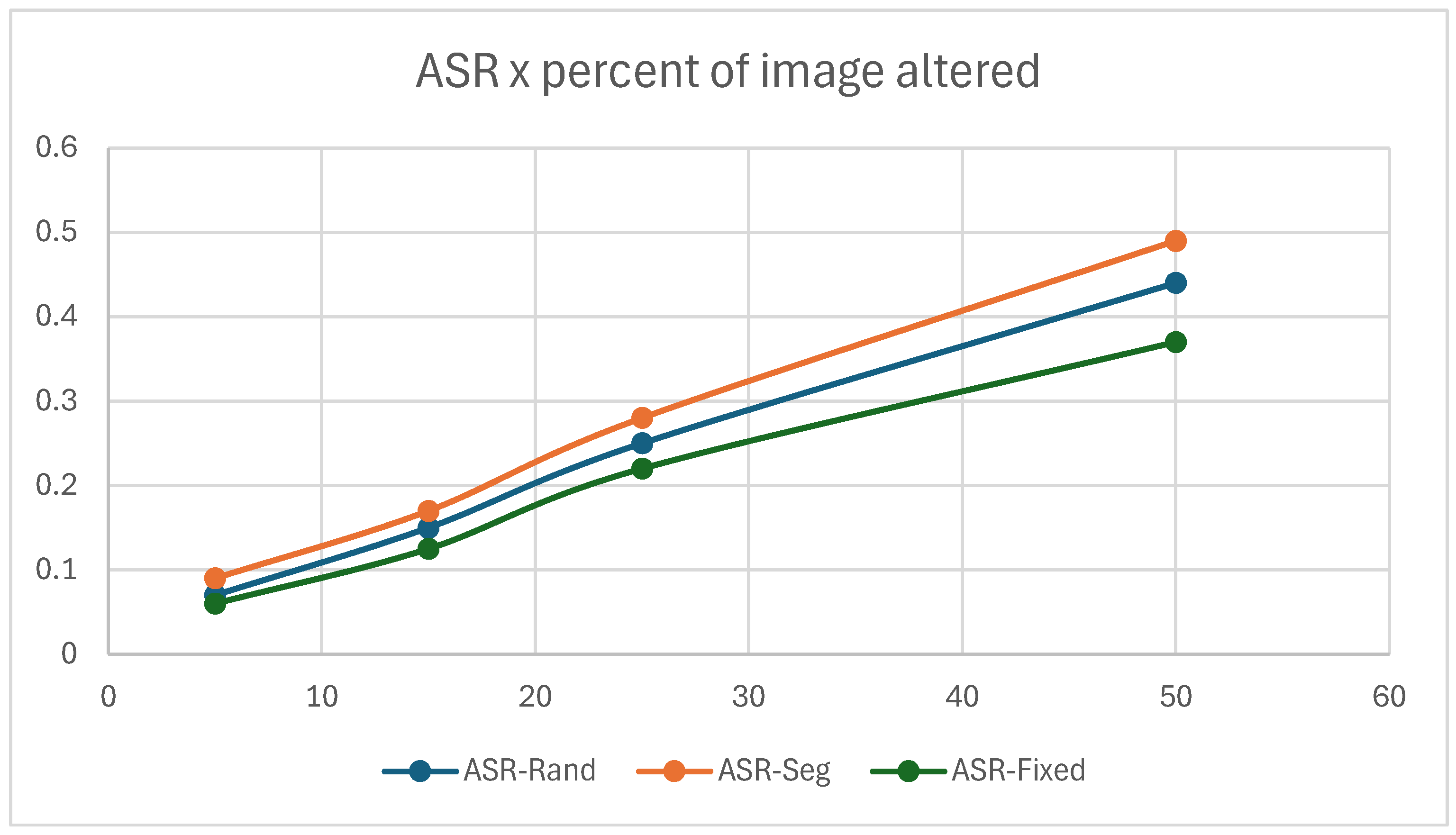

- Segmentation-guided placement. A fast, zero-gradient heuristic that selects high-impact locations via off-the-shelf semantic masks, boosting ASR by 8–13 pp over random or fixed baselines-even on adversarially trained networks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Universal and Physical Adversarial Patches

2.2. Patch Placement and Location Optimisation

2.3. Context Awareness and Adaptive Attacks

3. Dataset Design

3.1. Patch Source

3.2. Spatial Sweep

3.3. Model Attacked

3.4. Recorded Data Format

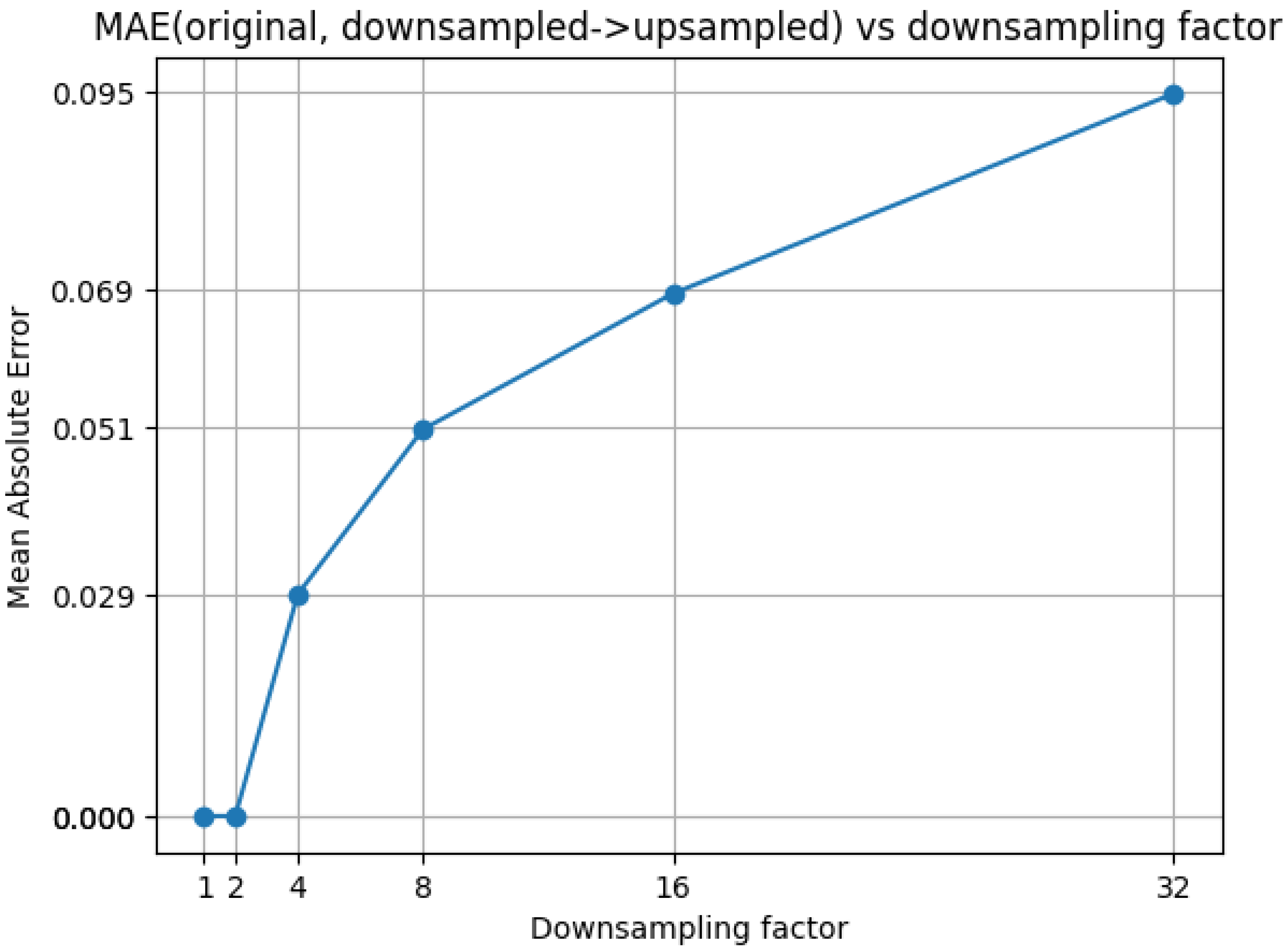

3.5. Choice of Parameters

3.6. Resources

3.7. Public Release

3.8. Why PatchMap?

4. Evaluation Protocol

- Location-wise attack-success heat-maps: For every grid cell we compute the clean-correct attack-success ratewhere is the number of validation images that the model classifies correctly without a patch. The resulting heat-map exposes systematic hot- and cold-spots.

- Confidence and calibration shift: Besides logits, PatchMap records soft-max scores, enabling reliability analysis. We report (i) the average confidence drop as detailed in (3). And (ii) the change in Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and Brier score between clean and patched images.

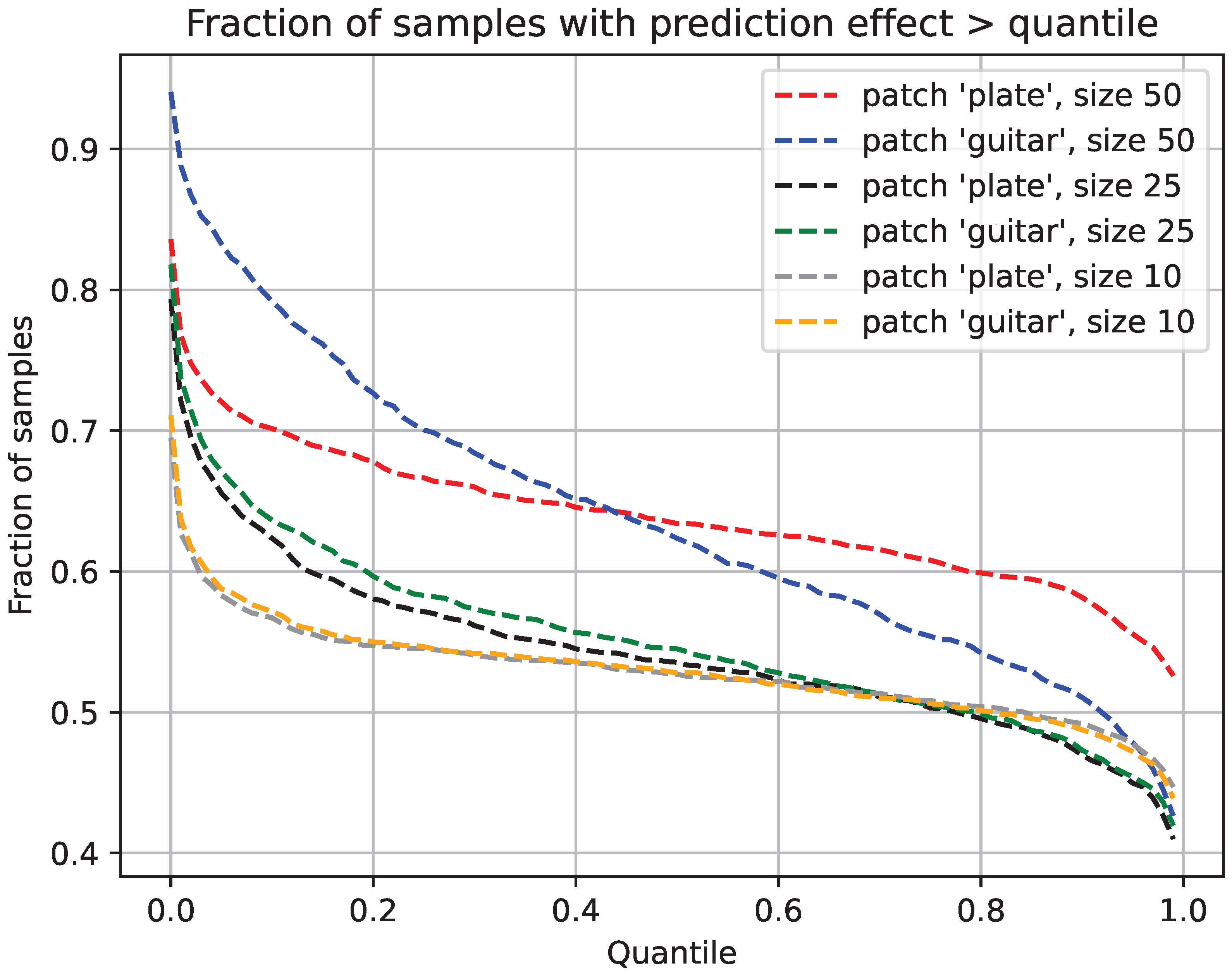

- Size/conspicuity trade-off: Plotting ASR against patch area across the three sizes yields a Pareto curve that answers: How small can a patch be before its success drops below a chosen threshold?

- Cross-model transfer: Given placements evaluated on model A, we re-score the exact locations on model B and assemble a transfer matrix . Off-diagonal strength indicates universal spatial vulnerabilities; weak transfer suggests architecture-specific quirks.

- Metrics are averaged over the full validation set and accompanied by bootstrap confidence intervals (1000 resamples). The public code reproduces every figure and table in under 2 GPU-hours on a single V100.

- PatchMap therefore enables fine-grained, statistically sound evaluation of both attacks and defences, opening the door to location-aware robustness research.

5. Analysis and Findings

5.1. Attack-Success Rate (ASR)

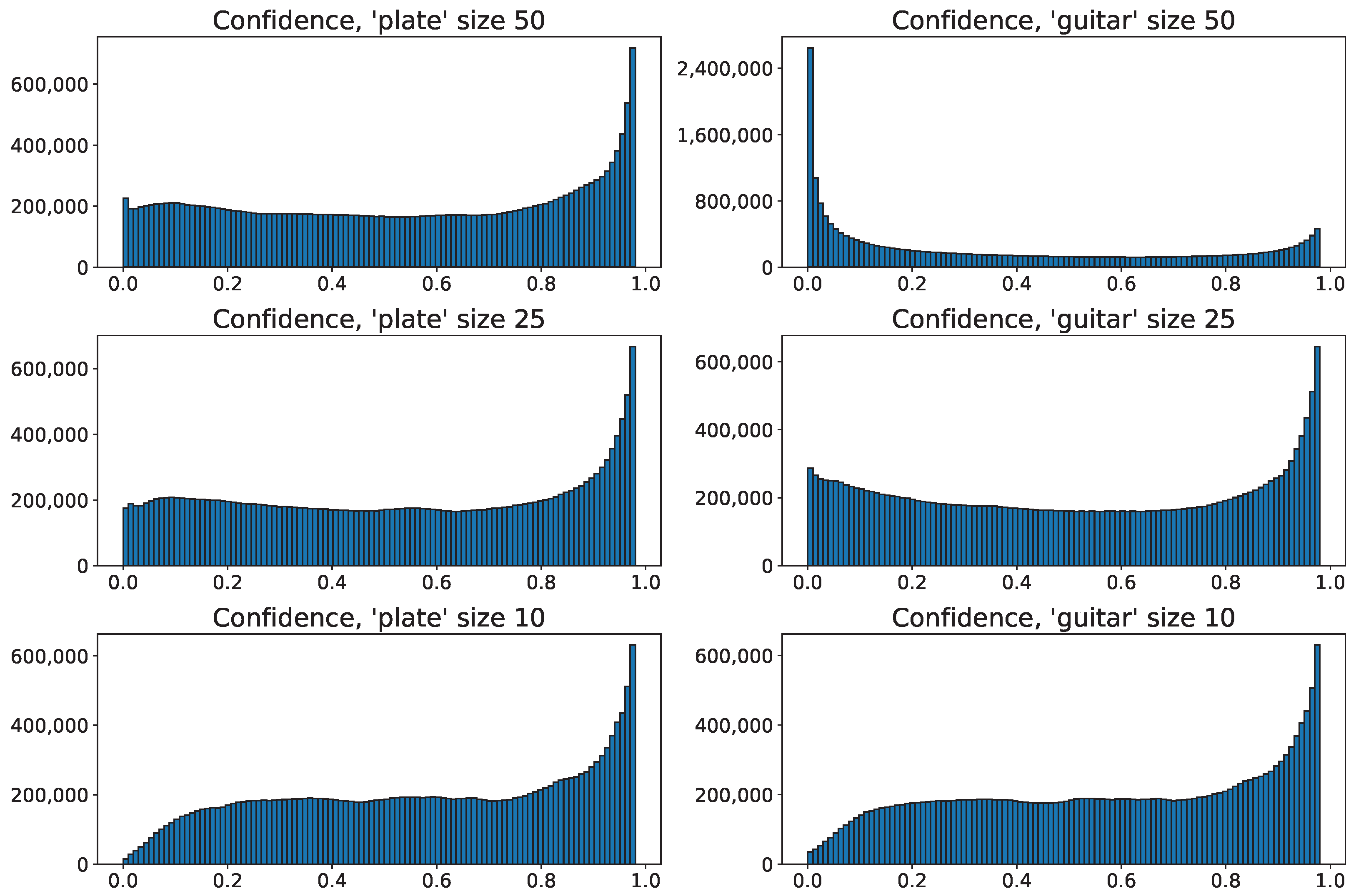

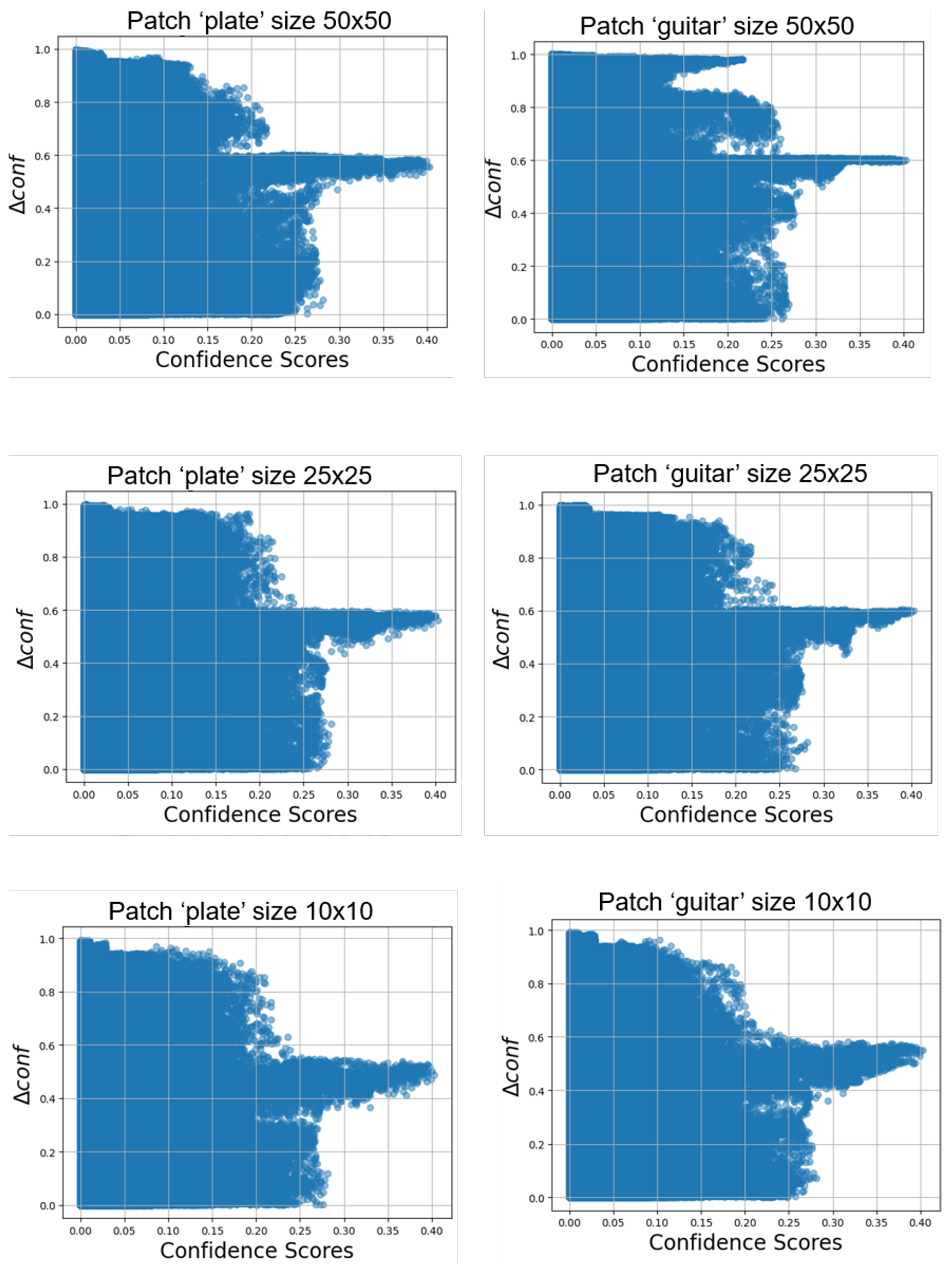

5.2. Confidence Effect

6. Segmentation-Guided Patch Placement

6.1. Motivation

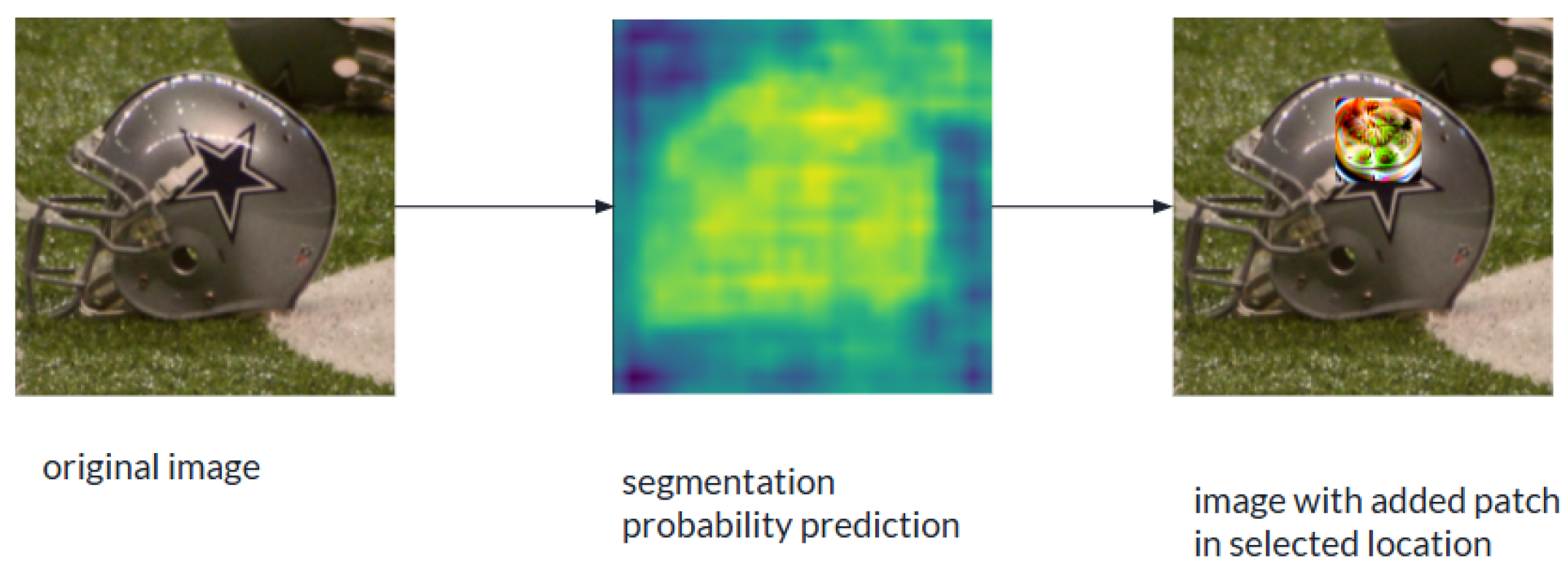

6.2. Approach

6.3. Experimental Setup

6.4. Overall Performance

6.5. Effect of Patch Size

6.6. Correlation with Confidence Drop

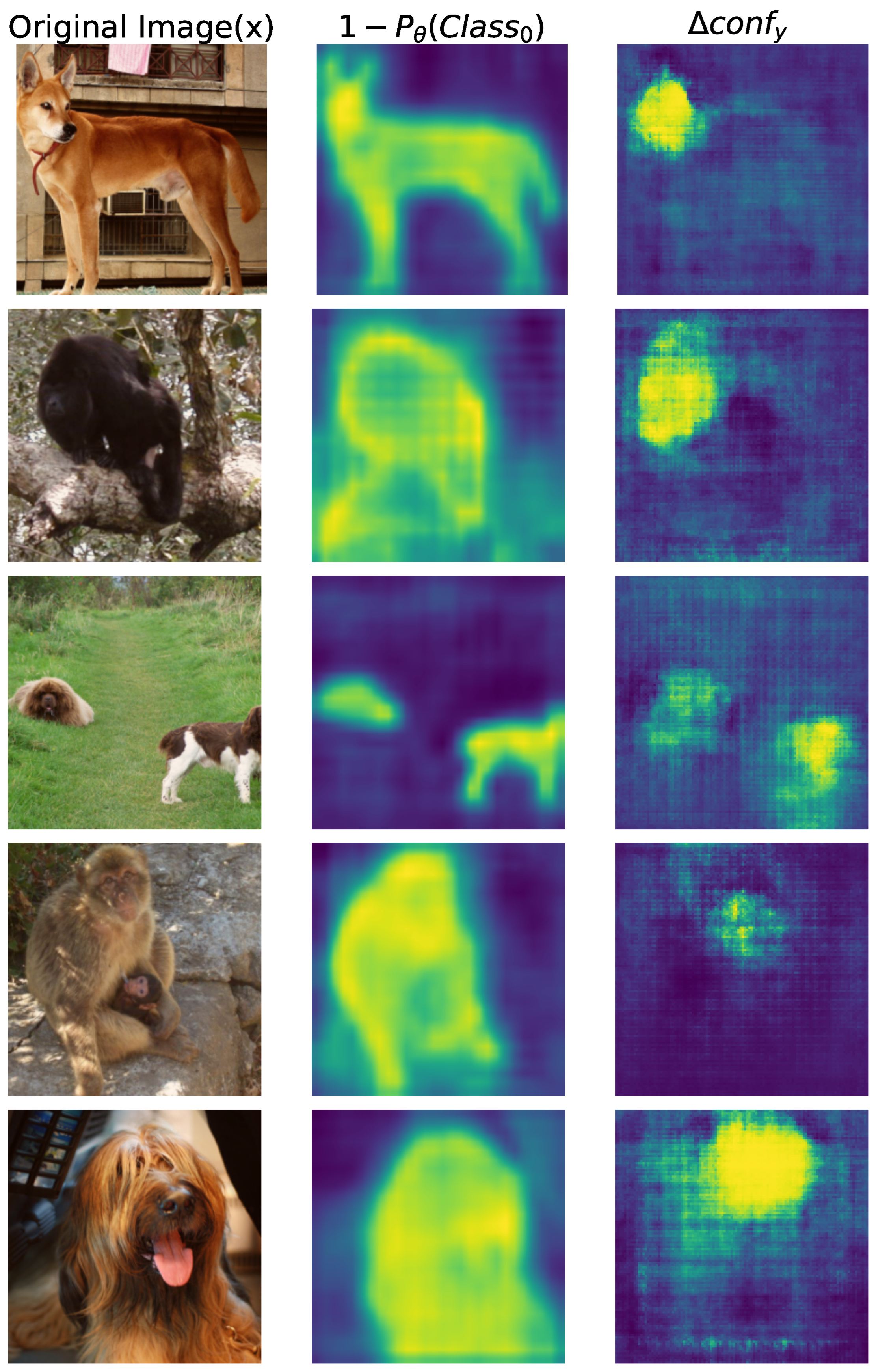

6.7. Qualative Examples

7. Conclusions

7.1. Task Scope

7.2. Segmentation Prior

7.3. Patch Transforms and Physical Realism

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, T.B.; Mane, D.; Roy, A.; Abadi, M.; Gilmer, J. Adversarial Patch. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09665. [Google Scholar]

- Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Xiao, C.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T.; Song, D. Robust Physical-World Attacks on Deep Learning Visual Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1625–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M.; Bhagavatula, S.; Bauer, L.; Reiter, M.K. Accessorize to a Crime: Real and Stealthy Attacks on State-of-the-Art Face Recognition. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1528–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.; Stutz, D.; Schiele, B. Adversarial Training Against Location-Optimized Adversarial Patches. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Glasgow, UK (Virtual Event), 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B. Simultaneously Optimizing Perturbations and Positions for Black-Box Adversarial Patch Attacks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 9041–9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yin, X.; Chuang, S.; van der Maaten, L.; Hadsell, R.; Feichtenhofer, C. ImageNet-Patch: A Dataset for Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Robustness in Image Classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.08649. [Google Scholar]

- Karmon, D.; Zoran, D.; Goldberg, Y. LaVAN: Localized and Visible Adversarial Noise. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Stockholmsmässan, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Dy, J., Krause, A., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 80, pp. 2507–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruoka, G.; Sato, T.; Chen, Q.A.; Nomoto, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Mori, T. Adversarial Retroreflective Patches: A Novel Stealthy Attack on Traffic Sign Recognition at Night. In Proceedings of the VehicleSec 2024: Symposium on Vehicle Security and Privacy (Poster/WIP), San Diego, CA, USA, 26 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Kortylewski, A.; Xie, C.; Cao, Y.; Yuille, A. PatchAttack: A Black-box Texture-based Attack with Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK (Virtual Event), 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J. Adversarial Sticker: A Stealthy Attack Method in the Physical World. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 2711–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingun, N.; Sitawarin, C.; Li, J.; Wagner, D. REAP: A Large-Scale Realistic Adversarial Patch Benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4640–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, S. Generative Dynamic Patch Attack. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC), Online, 22–25 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Liu, X.; Fan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, A.; Xie, H.; Tao, D. Perceptual-Sensitive GAN for Generating Adversarial Patches. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Bai, T.; Zhao, J. Generating Adversarial yet Inconspicuous Patches with a Single Image. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-21) Student Abstract and Poster Program, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 15837–15838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, S.H. POSES: Patch Optimization Strategies for Efficiency and Stealthiness Using eXplainable AI. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 57166–57176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, M.; Kimhi, S.; Zheltonozhskii, E.; Litany, O.; Baskin, C. Semi-Supervised Semantic Segmentation via Marginal Contextual Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2308.13900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, M.; Kerem, O.; Grad, E.; Rivlin, E.; Baskin, C. Noisy Annotations in Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10891. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 97, pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Rice, L.; Kolter, J.Z. Fast is better than free: Revisiting adversarial training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Virtual Event), 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11211, pp. 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.04597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, M.; Vainshtein, D.; Baskin, C.; Di Castro, D. Robot instance segmentation with few annotations for grasping. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 28 February–4 March 2025; pp. 7939–7949. [Google Scholar]

- Galil, I.; Kimhi, M.; El-Yaniv, R. No Data, No Optimization: A Lightweight Method to Disrupt Neural Networks with Sign-Flips. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.07408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, M.; Kashani, I.; Mendelson, A.; Baskin, C. Hysteresis Activation Function for Efficient Inference. In Proceedings of the 4th NeurIPS Efficient Natural Language and Speech Processing Workshop, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Patch Size | Patch |

|---|---|

| Patch 0 (“Soap Dispenser”) | 0.82 |

| Patch 1 (“Cornet”) | 0.78 |

| Patch 2 (“Plate”) | 0.84 |

| Patch 3 (“Banana”) | 0.78 |

| Patch 4 (“Cup”) | 0.78 |

| Patch 5 (“Typewriter”) | 0.83 |

| Patch 6 (“Guitar”) | 0.94 |

| Patch 7 (“Hair Spray”) | 0.80 |

| Patch 8 (“Sock”) | 0.76 |

| Patch 9 (“Cellphone”) | 0.76 |

| Benchmark | Task | l#Imgs | #Patches | Sizes | Loc/img | #Evals | ExhLoc | Cached |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet-Patch [6] | Cls | 50 k | 10 | 1 ( px) | 1 † | 50 k | × | × |

| REAP [11] | Det | 8433 | – | 3 ‡ | – | 14,651 | × | × |

| PatchMap (v1, ours) | Cls | 2 k | 2 (IDs 2,6) | 3 (10/25/50 px) | 12,544 | 150.5 M ⋆ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Patch Size | Patch 2 (“Plate”) | Patch 6 (“Guitar”) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.84 | 0.94 | |

| 0.79 | 0.82 | |

| 0.69 | 0.71 |

| Patch Size | Patch 2 | Patch 6 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.62 | 0.71 | |

| 0.60 | 0.62 | |

| 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Model | Random | Fixed | Seg-Guided |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Plate” | 4.98%) | ||

| Improvement | 0.052 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.39 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| EfficientNet-B1 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.42 |

| CLIP | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| “Plate” | 1.25%) | ||

| Average Improvement | 0.042 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.29 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| CLIP | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.43 |

| “Electirc Guitar” | 4.98%) | ||

| Average Improvement | 0.046 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.36 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.3 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.52 |

| CLIP | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.43 |

| “Electirc Guitar” | 1.25%) | ||

| Average Improvement | 0.030 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.22 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.28 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| CLIP | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.41 |

| “Typewriter Keyboard” | 4.98%) | ||

| Average Improvement | 0.058 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.26 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.48 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.52 |

| CLIP | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.41 |

| “Typewrtier Keyboard” | 1.25%) | ||

| Average Improvement | 0.024 | ||

| ResNet-50 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| + Adverserial Training [22] | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| ResNet-18 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| MobileNet-V2 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| CLIP | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.39 |

| Patch | Size | Random | Fixed | Seg-Guided |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.69 | |

| Plate | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kimhi, S.; Kimhi, M.; Mendelson, A. Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Selection and Location. Mathematics 2026, 14, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010103

Kimhi S, Kimhi M, Mendelson A. Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Selection and Location. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleKimhi, Shai, Moshe Kimhi, and Avi Mendelson. 2026. "Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Selection and Location" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010103

APA StyleKimhi, S., Kimhi, M., & Mendelson, A. (2026). Benchmarking Adversarial Patch Selection and Location. Mathematics, 14(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010103