1. Introduction and Basic Definitions

1.1. Permutations and Pattern Avoidance

Let denote the set of permutations of length (size) n. A pattern of length is a permutation in . A permutation avoids the pattern if does not contain any subsequence order isomorphic to .

A

(Babson–Steingrímsson-) pattern (or

vincular pattern)

of length

k is any permutation of

where two adjacent entries may or may not be separated by a dash, see [

1]. The absence of a dash between two adjacent entries in the pattern indicates that in any pattern-occurrence the two entries are required to be adjacent: a permutation

of length

contains the vincular pattern

, if it contains

as pattern and, moreover, there is an occurrence of the pattern

where the entries of

not separated by a dash are consecutive entries of the permutation

; otherwise,

avoids the vincular pattern

. Let

be a set of patterns. We denote by

the family of permutations of length

n that avoid any pattern in

, and by

. Two families of pattern avoiding permutations

and

are

Wilf-equivalent if

for all

n.

According to the previous definitions, classical patterns can be represented as vincular patterns where each entry is separated by a dash. For example,

denotes the family of permutations of length

n avoiding the classical pattern 231. For further details on pattern avoidance in permutations and related problems, we address the interested reader to [

2,

3].

1.2. Inversion Sequences

For , let . Given a permutation , its left inversion table is the array such that . It is well-known that is a bijection.

An inversion sequence of length n is any integer sequence satisfying , for all , i.e., an element of .

Let us consider the bijective mapping , such that is the reverse of the left inversion table of , precisely . This mapping (known as Lehmer code) is actually at the origin of the name “inversion sequences”, and is called the inversion sequence corresponding to.

The study of pattern-containment or pattern-avoidance in inversion sequences branched from pattern-avoiding permutations. It was first introduced in [

4], and then further investigated in [

5]. Namely, in [

4], Mansour and Shattuck studied inversion sequences that avoid permutations of length 3, while in [

5], Corteel et al. proposed the study of inversion sequences avoiding subwords (patterns) of length 3. The definition of inversion sequences avoiding patterns (which may in addition be permutations) is straightforward: for instance, the inversion sequences that avoid the pattern 110 (resp. 021) are those with no

such that

(resp.

). Moreover, if

P is a set of patterns, we denote by

the set of inversion sequences of length

n avoiding all patterns in

P, and by

.

In [

6], the notion of pattern avoidance was then further extended to triples of binary relations

. A handful of Wilf equivalences among the 343 possible sets of inversion sequences avoiding patterns of relation triples were conjectured in [

6] and proved later in [

7,

8,

9].

Equivalently to what happens for permutations, a vincular pattern in an inversion sequence is a pattern containing dashes showing the entries that do not need to occur consecutively. An inversion sequence e of length n contains the vincular pattern p of length k if there are such that the entries is order isomorphic to p and such that the entries which are not separated by dashes occur consecutively. Otherwise, e avoids p. For instance, the inversion sequence contains the pattern since for example the entries are order isomorphic to , but the inversion sequence avoids it (however, it contains the pattern 021).

Although permutations and inversion sequences are, in practice, the same objects, the avoidance of some (vincular) patterns in permutations can only seldom be translated into the avoidance of (vincular) patterns in inversion sequences. Therefore, in this paper we will study, using the concepts of underdiagonal paths and generating trees defined in the next section, some cases where the inversion sequences corresponding to a family of pattern avoiding permutations can be represented in terms of pattern avoidance.

1.3. Underdiagonal Paths

An

underdiagonal path of size

n [

10] is a lattice path made of up

, down

, west

steps, running from

to

, and such that

the path is weakly bounded by the lines and , and

a D (resp. W) step cannot be followed by a W (resp. D) step.

The up steps of an underdiagonal path P of size n will usually be referred to as , from left to right.

To an underdiagonal path P of size n, we can associate the inversion sequence , where is the distance of from the diagonal (see Figure 2). It readily follows that the mapping d is a bijection, thus the number of underdiagonal paths of size n is .

By abuse of notation, we will often represent an underdiagonal path as the word in the alphabet , obtained by reading its steps from left to right.

In this paper, we will consider several families of underdiagonal paths satisfying special constraints defined by the occurrence of certain factors. We will describe the paths in using the notion of edge line in a path P, which intuitively bounds the suffix of P. More precisely, each constraint we deal with is associated with an occurrence of a factor containing an up step denoted , for some i. The set of all factors determining the constraints will be denoted by (constraint set).

For , if belongs to a factor in , we define the edge line supporting as the line parallel to , and passing through . There can be several edge lines in P (for different ), and the rightmost one is called the edge line of P. By convention, we set to be the edge line supporting .

Every path P in a family with strong (resp. weak) constraint set (briefly, ) is such that, for every occurrence of a factor in (if any), the suffix of P to the right of the up step associated with that factor occurrence remains strictly (resp. weakly) below the edge line supporting .

Families of underdiagonal paths with constraint sets will be studied in

Section 3, and later.

1.4. Generating Trees

Consider a combinatorial class , that is to say a set of discrete objects equipped with a notion of size such that the number of objects of size n is finite for any n. We assume also that contains exactly one object of size 1. A generating tree for is an infinite rooted tree whose vertices are the objects of each appearing exactly once in the tree, and such that objects of size n are at level n (with the convention that the root is at level 1). The children of some object are obtained by adding an atom (i.e., a piece of object that makes its size increase by 1) to c. Since every object appears only once in the generating tree, not all possible additions are acceptable. We enforce the unique appearance property by considering only additions that follow some prescribed rules and call growth of the process of adding atoms according to these rules.

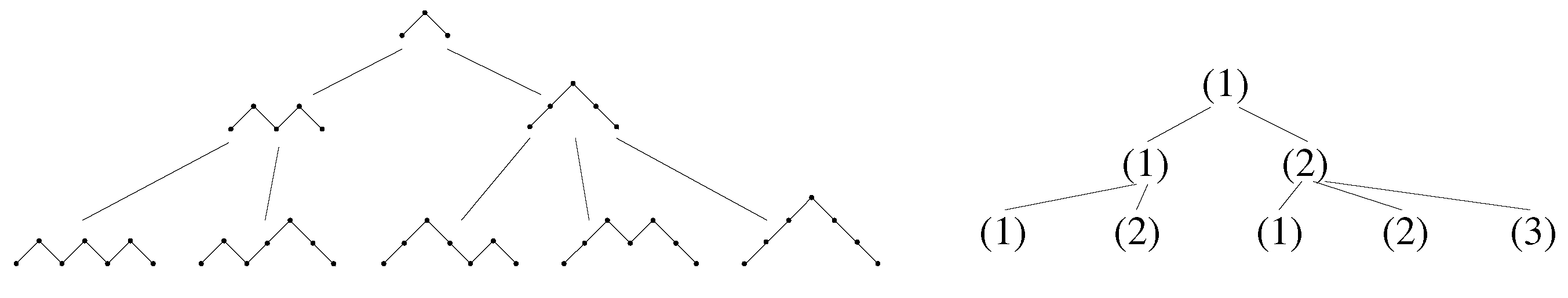

To illustrate these definitions, we describe the classical growth for the family of Dyck paths, as given by [

11]. Recall that a Dyck path of semi-length

n is a lattice path using up

and down

unit steps, running from

to

and remaining weakly above the

x-axis. Observe that Dyck paths are precisely all underdiagonal paths containing no

W steps (see Figure 3b for an example).

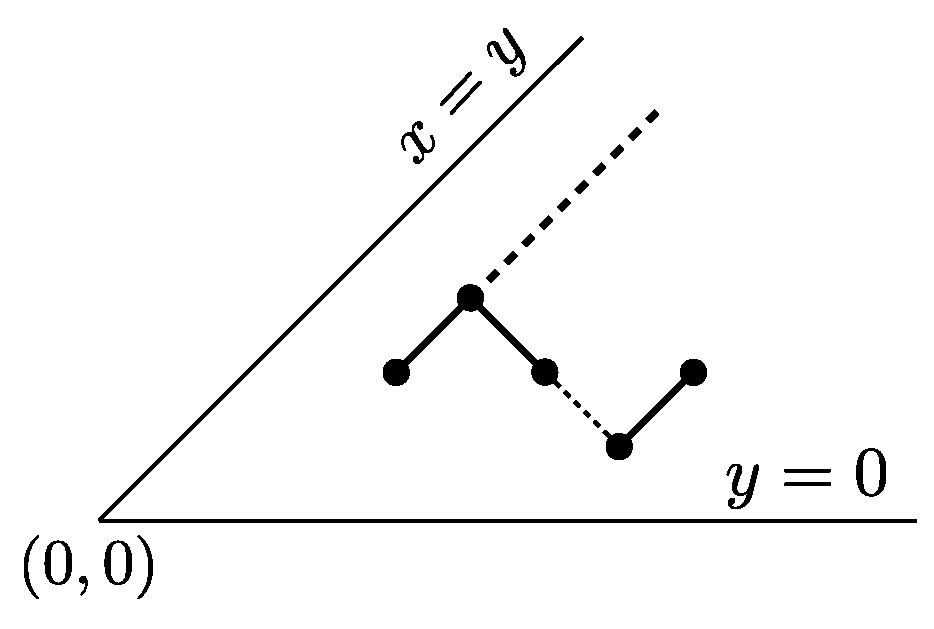

The atoms we consider are factors, a.k.a. peaks, which are added to a given Dyck path. To ensure that all Dyck paths appear exactly once in the generating tree, a peak is inserted only in a point of the last descent, defined as the longest suffix containing only D letters. More precisely, the children of the Dyck path are , ,..., , .

The first few levels of the generating tree for Dyck paths are shown in

Figure 1 (left).

When the growth of

is particularly regular, we encapsulate it in a

succession rule. This applies more precisely when there are statistics whose evaluations control the number of objects produced in the generating tree. A succession rule consists of one starting label (

axiom) corresponding to the value of the statistics on the root object and of a

set of productions encoding the way in which these evaluations spread in the generating tree–see

Figure 1 (right). The growth of Dyck paths presented earlier is governed by the statistics “length of the last descent”, so that it corresponds to the following succession rule, where each label

indicates the number of

D steps of the last descent in a Dyck path,

Obviously, as we discuss in [

12], the sequence enumerating the class

can be recovered from the succession rule itself without reference to the specifics of the objects in

: indeed, the

nth term of the sequence is the total number of labels (counted with repetition) that are produced from the root by

applications of the set of productions, or equivalently, the number of nodes at level

n in the generating tree. For instance, the well-know fact that Dyck paths are counted by Catalan numbers (sequence A000108 in [

13]) can be recovered by counting nodes at each level

n in the above generating tree.

For more details about generating trees, and the solution of the associated functional equations we address the reader to [

11,

14,

15].

1.5. Contents of the Paper

Composing the bijections:

- (1)

between permutations of length n and inversion sequences of length n, and

- (2)

between inversion sequences of length n and underdiagonal paths of size n,

we obtain a bijection

P between permutations of length

n and underdiagonal paths of size

n. So, given

, and

the inversion sequence corresponding to

,

is the unique underdiagonal path of size

n with up steps

, where the distance of

from the diagonal

is given by

. On the other side, given an underdiagonal path

P of size

n, we define

as the permutation of length

n such that

(see

Figure 2).

The aim of this paper is to study and enumerate families of underdiagonal paths which are obtained by restricting the bijection P to subclasses of avoiding some vincular patterns.

For a given pattern

, we will focus on the family

of underdiagonal paths

corresponding to permutations in

, precisely:

and the family

of inversion sequences

corresponding to permutations in

, precisely:

We will focus our investigation on patterns of length 3 and 4. Precisely:

- (1)

patterns of length 3 of type:

, where

, precisely

,

,

,

(

Section 2);

- (2)

patterns of length 3 of type:

, where

, precisely

,

(

Section 3);

- (3)

patterns of length 4 of type:

, where

,

, precisely

,

,

,

(

Section 4).

We will reach our goal by providing, for each pattern above, a characterization of the underdiagonal paths of in terms of geometrical constraints, or equivalently, in terms of the avoidance of some specific configurations, which will be formalized by the avoidance of some factors in the words coding the path. Moreover, we will give a characterization of the inversion sequences of , in terms of pattern avoidance. Finally, we will determine a recursive growth of these families by means of generating trees and then, when it is possible, find their enumerative sequence.

We point out that, for all the patterns of length 3 not listed above (and not equivalent to one of them up to symmetries), it is not possible to provide a characterization of the corresponding families of inversion sequence in terms of pattern avoidance, hence of the associated underdiagonal paths.

Finally, we would like to point out that the investigation of underdiagonal paths and their connections with pattern avoiding permutations was started in [

10], with the introduction and the study of

steady paths, which will be recalled in

Section 3.

2. Patterns of Length 3: , with

In this section, we will take into account the study of families of underdiagonal paths corresponding to permutations avoiding one pattern , where (namely, , , , or ).

2.1. The Family : Dyck Paths

It is known (and easy to prove) that a permutation avoids the vincular pattern

if and only if it avoids the classical pattern

, thus

. It is also known [

16] that the cardinality of

is given by the

nth Catalan number.

We will give a further proof of this fact by showing that is the family of Dyck paths, i.e., underdiagonal paths without W steps.

Proposition 1. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is a Dyck path.

Proof. We proceed by contrapositive, proving that contains a W step if and only if contains the pattern . So, let contain a factor , with , . Then, with , we have that is the left inversion table of , and . This occurs if and only if , and moreover, there is some such that (otherwise, ). So, gives rise to an occurrence of in . □

The following is a neat consequence of Proposition 1.

Corollary 1. .

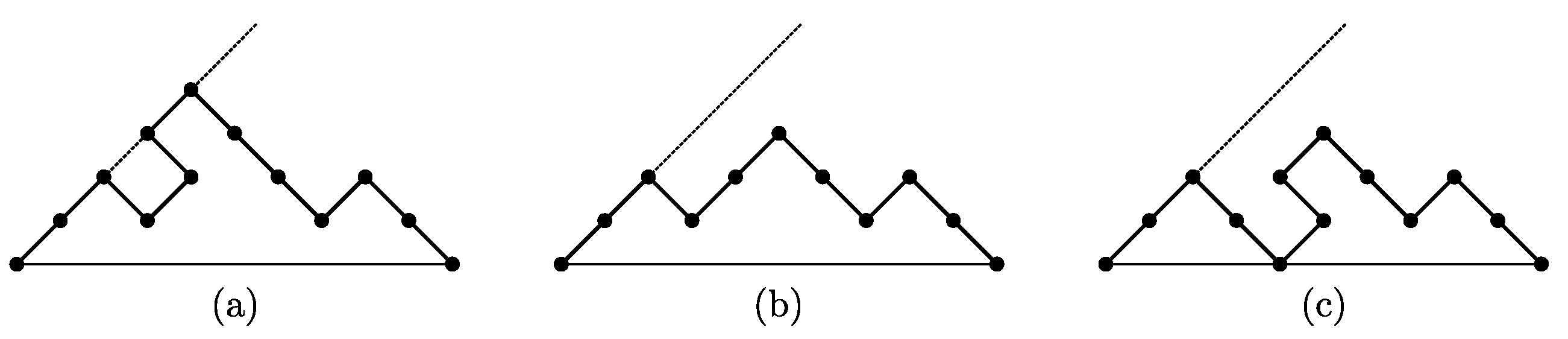

2.2. The Family : -Avoiding Paths

An underdiagonal path

P is

-avoiding path if every factor

and

in

P is such that the up step

lies on the diagonal

(

Figure 3).

Proposition 2. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is a -avoiding path.

Proof. We proceed by contrapositive, proving that

contains a factor

or

, where

U is not on the diagonal, if and only if

contains the pattern

. Then, let

contain a factor

, with

, for some

,

. Therefore, the left inversion table of

is as follows:

with

. This is equivalent to saying that

. Moreover, since

, there is some

such that

forms a pattern

. □

We recall from [

2] that the family of permutations avoiding the pattern

is enumerated by the Bell numbers (sequence A000110 in [

13]). So, we have that

Corollary 2. For any , the number of -avoiding paths of size n is given by the nth Bell number.

Corollary 3. , i.e., inversion sequences avoiding both vincular patterns , and .

Proof. An inversion sequence corresponds to a -avoiding path P, i.e., if and only if there is no index such that , thus it avoids both patterns and . □

2.3. The Family : -Avoiding Paths

An underdiagonal path P is -avoiding if it does not contain any factor .

Proposition 3. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is a -avoiding path.

Proof. We prove that contains a factor if and only if contains a pattern . Suppose there is an index i, , such that contains the factor , . Therefore, . Correspondingly, in the left inversion table of , we have . This occurs if and only if and there is a such that , so forms a pattern . □

Since the family of permutations avoiding the pattern

is enumerated by the Catalan numbers [

1], we have that

Corollary 4. For any , the number of -avoiding paths of size n is given by the nth Catalan number.

From the proof of Proposition 3, we immediately have that is given by the inversion sequences such that there is no index satisfying . This property cannot be expressed in terms of classical pattern avoidance, and by abuse of notation we write this family as .

2.4. The Family : -Avoiding Paths

An underdiagonal path

P is

-avoiding if, for every factor

, the first

U step lies on the diagonal

(see

Figure 4).

Proposition 4. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is a -avoiding path.

Proof. We proceed by contrapositive, proving that contains a factor such that the first U step is not on the diagonal if and only if contains a pattern . So, let us assume that there is an index i, such that contains the factor and is not on . Therefore, . Using the same arguments as in the proofs above, this leads to an occurrence of the pattern in . □

Since the family of permutations avoiding the pattern

is enumerated by the Bell numbers [

1], we have that

Corollary 5. For any , the number of -avoiding paths of size n is given by the nth Bell number.

From the proof of Proposition 4, we immediately have that

Corollary 6. .

4. Patterns of Length 4: , with ,

We study the patterns , , , separately.

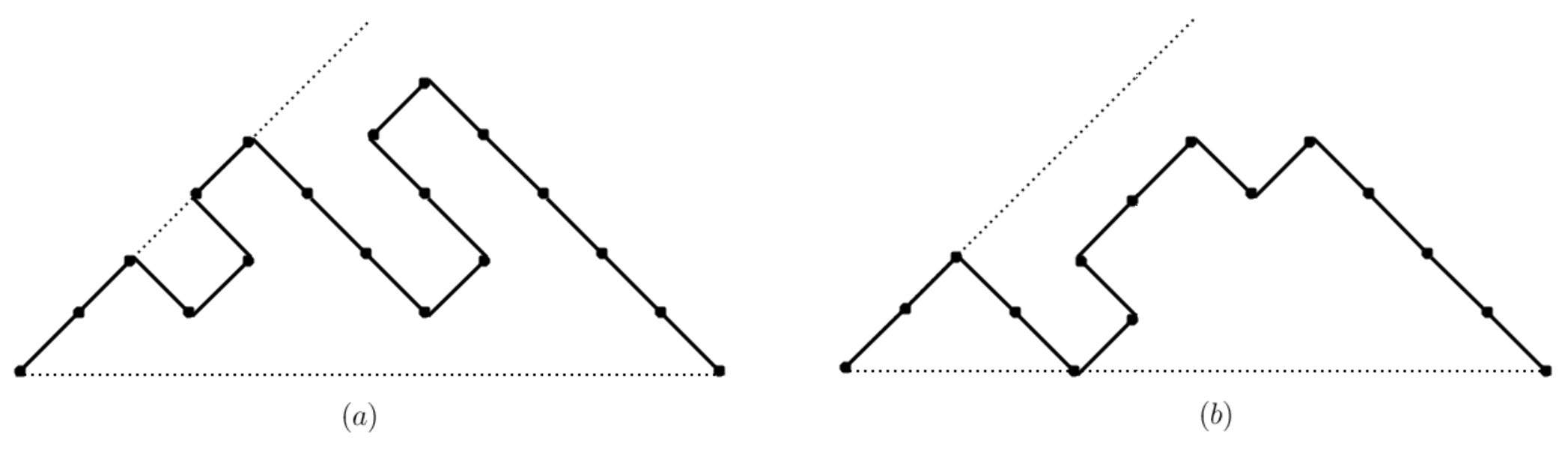

4.1. The Family : Steady Paths

Steady paths are underdiagonal paths with weak constraint set .

More precisely, an underdiagonal path P is a steady path if the two following conditions are satisfied:

- (S1)

for every factor of P, the suffix of P following lies weakly below the line parallel to , and passing through .

- (S2)

for every factor of P, the suffix of P following lies weakly below the line parallel to , and passing through .

Clearly, a strong steady path is also a steady path, while the converse does not hold.

Figure 7a shows an example of a steady path; it contains a factor

and a factor

, and both are supported by the edge line

, which is also the edge line of the path.

Figure 7b shows a steady path where the edge line is the line supporting

, precisely,

.

Figure 7c,d shows two different examples of underdiagonal paths that are not steady paths. We also point out that steady paths are a subfamily of the “skew Dyck paths” studied in [

17].

Steady paths were introduced in [

10], as one of the several combinatorial families enumerated by powered Catalan numbers. The investigation of [

10] starts from powered Catalan inversion sequences

, and then the authors provide bijections among the families enumerated by their number sequence.

The sequence of

powered Catalan numbers is registered on [

13] as A113227, and its first terms are as follows:

D. Callan [

18] proves that the

nth term of the sequence can be obtained as

, where

is recursively defined by the following:

Proposition 7 ([

5], Theorem 13)

. For and , the number of powered Catalan inversion sequences having k zeros is given by the term of Equation (1). Thus, the number of powered Catalan inversion sequences of length n is , for every . Proposition 7 can be rephrased in terms of succession rules, as conducted below with the rule

. More precisely, for

and

, the number of nodes at level

n that carry the label

in the generating tree associated with

is precisely the quantity

given by Equation (

1).

Proposition 8. The family of powered Catalan inversion sequences grows according to the following succession rule We notice that is extremely similar to the Catalan succession rule (see page 4): specifically, the productions of are the same as in , but with multiplicities appearing as “powers”. Hence, the name powered Catalan.

The authors of [

10] prove the following statements (we report here the proof for the sake of completeness):

Proposition 9. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is a steady path.

Proof. As usual, we will proceed by contrapositive. Let P be an underdiagonal path of size n which is not steady. So, one of the two conditions (S1) or (S2) must be violated, i.e., there must be in P an up step not lying on the main diagonal such that it forms a factor either or , and an up step , which is on the right of , lying above the edge line supporting .

First, suppose forms a factor . Then, in , we have and , with . Let us consider then the permutation with the left inversion table , i.e., such that . It holds that . Moreover, since , there is an index such that and . Therefore, is an occurrence of the pattern .

On the other hand, if forms a factor , there exists such that . Then, in we have , with . Let be the permutation with left inversion table . It holds that . Moreover, since , there is an index such that and . Finally, is an occurrence of the pattern .

The above argument can be inverted proving that, if

is a permutation containing an occurrence of

, then

is not steady (see also [

10]). □

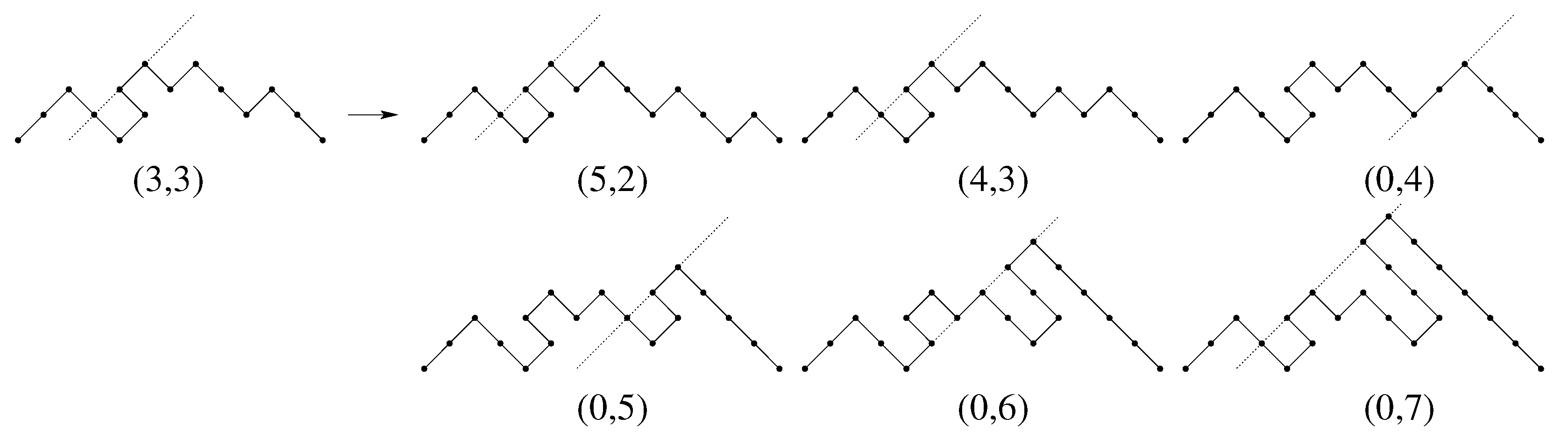

We provide growth for the family of steady paths that result in the following proposition.

Proposition 10. The family of steady paths grows according to the following succession rule: Proof. We start observing that every steady path P of size ends with a factor , with , and that by removing the factor from P we obtain a steady path of size n. So, we define a recursive growth of steady paths, such that every steady path of size is uniquely produced from a steady path of size n by adding the last up step, and prove that this growth can be described by the succession rule .

Let P be a steady path of size n, ending with a factor , with . Let us denote its last up step by . We assign to P the label , where

h is the distance between and the edge line of P, if any; otherwise, h is the distance between and the diagonal ;

, i.e., k is one more than the length of the last descent of P.

Then, , whereas . The steady path of minimal length has label .

The steady path P of label produces steady paths of size , by applying the following operations:

We add an occurrence of just following a sequence of t consecutive down steps in the last descent, with . For every t, this operation produces a steady path with the label .

We add an occurrence of just following , thus producing a factor . Therefore, the obtained steady path has an edge line passing through , hence its label is .

We add an occurrence of just following , with . Therefore, we obtain a new occurrence , in the rightmost position, and then the edge line of the obtained path passes through the added up step. The label of this path is .

Hence, steady path growth can be described by means of the succession rule . □

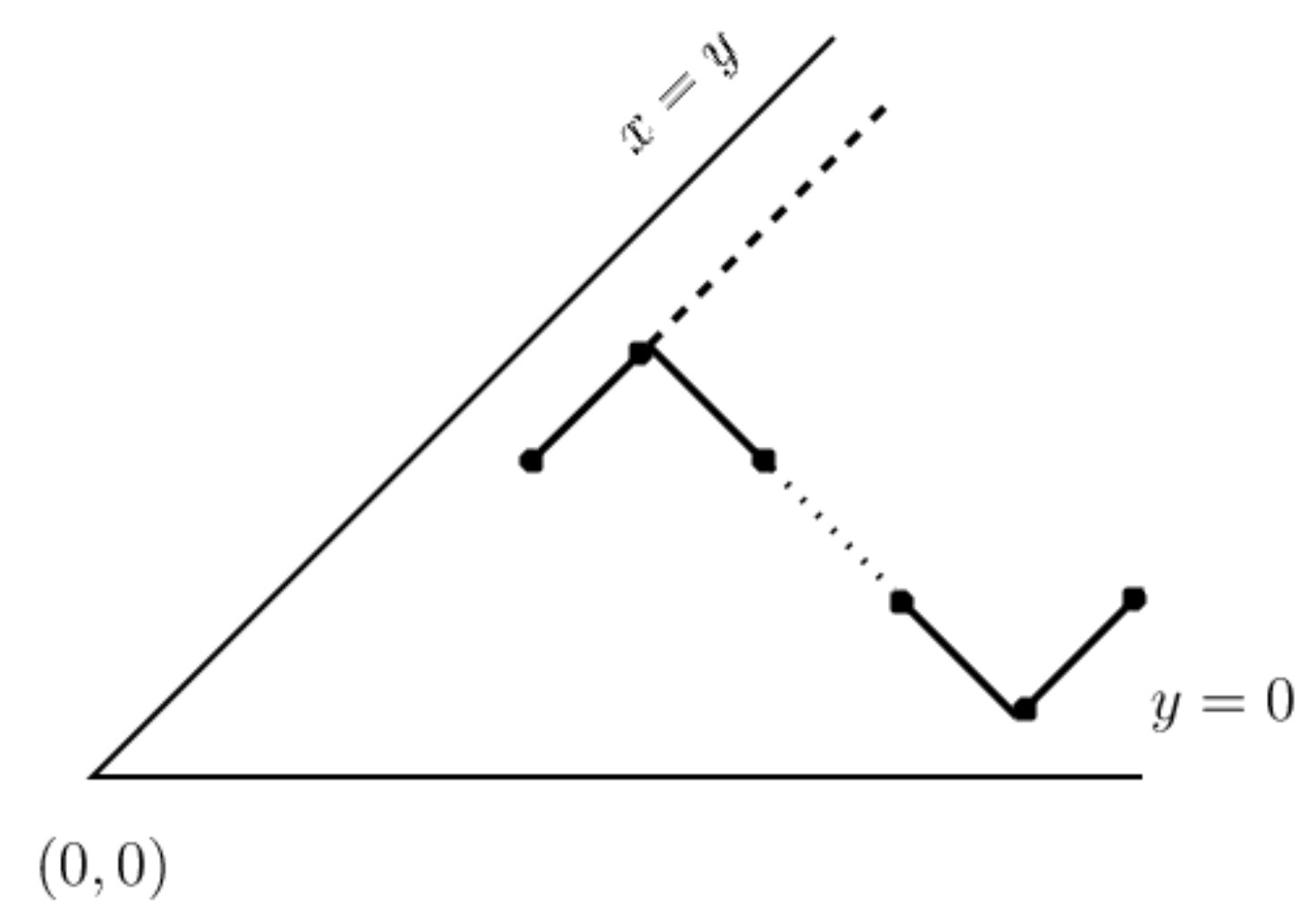

Figure 8 depicts the growth of a steady path of size

n with edge line

; for any path, the corresponding edge line is drawn.

From the proof of Proposition 9, we immediately have the following corollary (not reported in [

10]):

Corollary 11. .

4.2. The Family : -Constrained Paths

-constrained paths are underdiagonal paths with weak constraint set

for any

. Precisely, a

-constrained path

P is a path such that, for every factor

of

P,

,

, the suffix of

P on the right of

lies weakly below the line parallel to

, and passing from

, i.e., the edge line supporting

(see

Figure 9).

Proposition 11. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is -constrained.

Proof. As usual, we will proceed by contrapositive. Let P be an underdiagonal path of size n which is not -constrained. So, there are indices , and , such that , , is a factor of P, and lies above the edge line supporting . Therefore, in we have . Let us consider then the permutation with the left inversion table , i.e., such that . It holds that . Moreover, since , there is an index such that and . Finally, is an occurrence of the pattern .

The above argument can be neatly inverted proving that if is a permutation containing an occurrence of , then is not -constrained. □

Proposition 12. The number of -constrained paths of size n is the nth-powered Catalan number.

Proof. We prove it by showing that

grows according to the following rule:

which governs the growth of steady paths enumerated by powered Catalan numbers.

Let

. We make it grow by adding an entry

on the right, and we denote by

the obtained permutation. More precisely, the entry

of

is as follows:

We say that

x is an active entry of

if

avoids the pattern

. Precisely, if there are indices

, with

, such that

is an occurrence of

, i.e.,

, then every entry

is not active. Therefore, for any occurrence

of the pattern

, if

, then all the entries

are not active.

Let

h (resp.

k) denote the number of active entries less than or equal to (resp. greater than)

, with one subtracted (resp. added) to the count. Observe that entries 1 and

are always active, thus

and

. For the permutation

, both 1 and 2 are active entries, and thus

and

. Then, the label of the permutation

is

, which satisfies the axiom of

. The proof then concludes by showing that for any

of label

, the permutations

have labels according to the productions of

, if

x spans all active entries of

. To prove this, we need to distinguish between the following cases (see also the example in

Figure 10):

: in this case , for all , and . The last two entries of do not produce a new occurrence of , so has the same active entries as , plus the active entry . Since all the active entries apart from 1 are greater than , has label .

: in this case and . The entries of produce a new occurrence of , so all the entries that are smaller than or equal to x are not active for (apart from the entry 1). Suppose x is the ith active entry of smaller than or equal to (but ), where , then has label .

: in this case and the entries of produce an ascent. Then, has the same active entries as , plus the active entry . Suppose x is the jth active entry of greater than , where , then has label .

□

Remark 2. Although both steady paths and UDU-constrained paths are enumerated by the sequence of powered Catalan numbers, we have not been able to find a direct bijection between the two families. Thus, we leave the question of establishing a correspondence as an open problem for further investigation.

From the proof of Proposition 11 it follows that

Proposition 13. .

4.3. The Family : Strong -Constrained Paths

Strong -constrained paths are underdiagonal paths with a strong constraint set

for any

. Precisely, a strong

-constrained path

P is a path such that, for every factor

of

P,

,

, the suffix of

P to the right of the factor

lies strictly below the line parallel to

, and passing from

, i.e., the edge line of

P supporting

(see

Figure 11).

Proposition 14. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is strong -constrained.

Proof. As usual, we will proceed by contrapositive. Let be an underdiagonal path of size n which is not strong -constrained. So, there are indices , and , such that , , is a factor of and lies weakly above the edge line supporting . Then, in , we have , and . Accordingly, in the permutation , from , we have that . Moreover, since , we have that and there is a k greater than such that . Thus the entries form an occurrence of .

The above argument can be neatly inverted proving that if is a permutation containing an occurrence of , then is not strong -constrained. □

From the proof of Proposition 14, we immediately have that is given by the inversion sequences such that there are no indices satisfying and . This property cannot be expressed in terms of classical pattern avoidance, and by abuse of notation we write this family as .

Remark 3. The permutations avoiding the pattern are the same as permutations avoiding the “barred pattern” , where a barred pattern is a pattern where some of the entries are barred. For a permutation π, to avoid the barred pattern τ means that every subsequence of π which is order-isomorphic to the sequence of unbarred entries of π can be extended (exactly to the positions) to the one in π order-isomorphic to τ. So, in practice, the avoidance of in π requires that every occurrence of 2534 in π is contained in an occurrence of a 25134.

Since permutations avoiding

are enumerated by sequence A137538 in [

13], from Proposition 14 it follows

Corollary 12. The family of strong -constrained paths is enumerated by the sequence A137538 in [13]. The first terms of A137538 are as follows:

We point out that the reference in [

13] does not give any further information about the properties of the sequence. Therefore, in this section, our aim is to provide more information about the sequence, and we start determining a growth for the family of strong

-constrained paths by means of a generating tree.

Proposition 15. The family of strong -constrained paths grows according to the following succession rule Proof. We define a a recursive growth for strong -constrained paths such that every path of size is uniquely produced from a path of size n by adding the last up step and prove that this growth can be described by the succession rule .

Let P be a strong -constrained path of size n, and let be its last up step. To P we assign the label , where

h is the distance between and the edge line of P; observe that if the edge line of P passes through , then ;

k is the length of the last descent of P plus one. Then, , and .

The path of size 1 has label .

The path P with label produces strong -constrained paths of size , by applying the following operations:

add a factor following , with . For every t, this operation produces a strong -constrained path with the label .

add a factor following , thus obtaining a factor . Then the obtained path has the label .

add a factor following , thus obtaining a factor . Then the obtained path has the label .

add a factor immediately following a sequence of t consecutive down steps in the last descent, with , thus obtaining the factor , then the obtained path has the edge line supporting , so it has label .

Finally, strong -constrained paths grow according to the rule . □

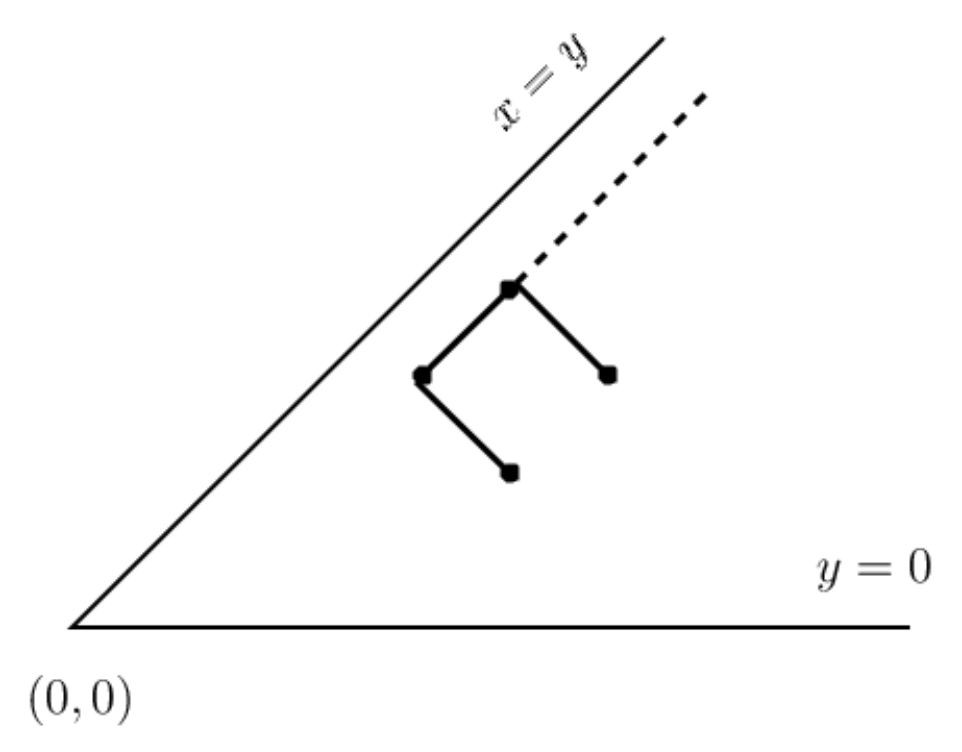

Figure 12 depicts the growth of a strong

-constrained path of size 5; for any path, the rightmost edge line is drawn.

Using standard techniques [

11,

14] we can translate the rule

into the setting of generating functions. For

and

, let

denote the generating function of strong

-constrained paths having label

and let

The generating function of strong -constrained paths is thus . The rule translates into a functional equation for the multivariate generating function of strong -constrained paths.

Proposition 16. The generating function satisfies the following functional equation: Proof. It follows from the productions of the rule

:

□

Replacing

in the previous equation, we obtain the following relation:

4.4. The Family : Strong -Constrained Paths

Strong -constrained paths are underdiagonal paths with strong constraint set

. Precisely, a strong

-constrained path

P is a path such that, for every factor

of

P (if any),

, the suffix of

P on the right of this factor lies strictly below the line parallel to

, and passing through

, i.e., the edge line supporting

(see

Figure 13).

Proposition 17. Let π be a permutation of length n. Then, if and only if is strong -constrained.

Proof. As usual, we will proceed by contrapositive. Let be an underdiagonal path of size n which is not strong -constrained. So, there are indices , such that , with , is a factor of , and lies weakly above the edge line supporting . Therefore, in we have . Accordingly, in the permutation , from , we have that . Moreover, since , we have that and there is a k greater than such that . Thus the entries form an occurrence of .

The above argument can be neatly inverted proving that if is a permutation containing an occurrence of , then is not strong -constrained. □

From the proof of Proposition 17, we immediately have that

Corollary 13. .

We will prove that strong

-constrained paths, as strong

-constrained paths, are enumerated by the sequence A137538 in [

13]. Although we do not have a direct bijection between the two families of paths, we will show a bijection between the two corresponding families of permutations, borrowed from [

19].

Proposition 18. The families and are Wilf-equivalent.

Proof. We define a recursive bijection which preserves the left-to-right minima. We recall that an entry of is a left-to-right minima if, for any , then .

So, let

. We decompose

as follows:

where

, and

are the left-to-right minima of

. We observe that

avoids the pattern

, since

is on the left of

, and the presence of a pattern

in

would imply a pattern

in

. Assuming that

, with

, let

be the set of entries of

on the right of

which are greater than

. Let

be the entries of

(if not empty). Let us define the following:

;

, with ;

.

If is empty, then we set .

All the entries of must be on the right of all the elements of , for all . Indeed, if an entry of was on the left of some entry of , , then would contain an occurrence of , where plays the role of 1, and plays the role of 3.

Repeating the same argument, we can prove that every entry of

must be on the right of all entries of

, with

. So,

can be decomposed as follows:

We also observe that every

should avoid the pattern

, because of the entry

on the left (since

is less than every entry of

).

For a given permutation , let be the set of entries obtained by replacing the entry h by the entry . We observe the mapping′ is bijective and transforms every pattern into a pattern .

Then, for every

i such that

, let us define

as follows:

where

is obtained applying the mapping′ on the reduced permutation of

. Finally, we define

as follows:

Then, , and has the same left-to-right minima as . □

Table 2 summarizes the obtained results about patterns of length 4.

5. Further Work

In this paper, we started from a simple representation of permutations as lattice paths, called underdiagonal paths, and then studied families of underdiagonal paths which are obtained by restricting ourselves to subclasses of permutations avoiding some vincular patterns . We have considered patterns of length 3 and 4, and provided a combinatorial characterization and the enumeration of the corresponding paths .

We believe that this study looks promising and should be extended to patterns of greater lengths, starting with length 5. Some partial results in this direction were obtained by studying families of underdiagonal paths satisfying only one of the two conditions (S1) and (S2) of steady paths. A (positive) result is that underdiagonal paths satisfying condition (S2) (-constrained paths) are those corresponding to the patterns , precisely . On the other side, underdiagonal paths satisfying condition (S1) cannot be characterized in terms of properties of the sequence , hence of geometrical constraints.

Another remarkable problem that should be faced is the most general problem of providing a structural or combinatorial characterization of patterns such that the family can be described in terms of constrained underdiagonal paths.