Enhancing Predictive Accuracy in Medical Data Through Oversampling and Interpolation Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Binary Classification Dataset

2.2. The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique

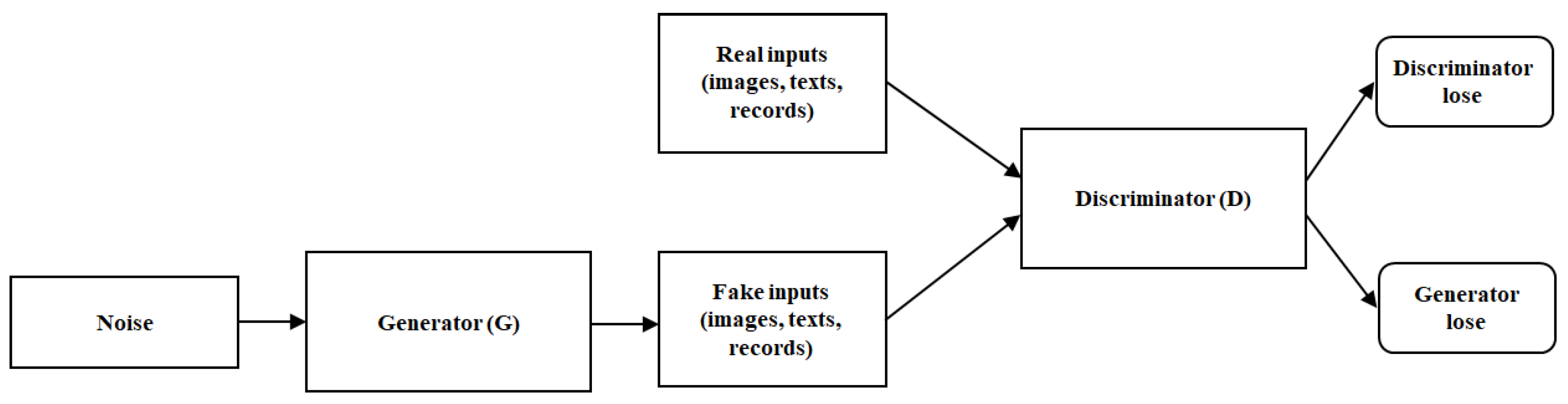

2.3. The Generative Adversarial Network

2.4. The Conditional-Tabular Generative Adversarial Network

2.5. Augmented Data Validation Techniques

- Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) Test: Measures the maximum discrepancy between the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of and .A smaller D suggests closer alignment between the two distributions.

- Kernel Density Estimation (KDE): Provides a non-parametric estimate of a probability density function (PDF). For we estimate , and for we estimate , withwhere h is the bandwidth and K the kernel function.

- Wasserstein Distance: also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD), quantifies the minimum cost required to transform one distribution into another. For and , the Wasserstein distance of order is defined aswhere represents all joint distributions with marginals and - Lower values indicate better alignment between distributions.

- Kullback–Leibler Divergence: measures how one probability distribution Q diverges from a reference distribution P. The Kullback–Leibler divergence is defined aswhere lower values indicate that Q is a better approximation of P. Note that is non-symmetric and non-negative.

- Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD): quantifies the difference between two probability distributions. For probability distributions P and Q, the Jensen–Shannon divergence iswhere is the average distribution and is the Kullback–Leibler divergence. Smaller values indicate higher similarity.

- Anderson–Darling Test: assesses whether a sample follows a specific distribution by measuring the weighted squared distance between the empirical and theoretical CDFs. The test statistic iswhere F is the theoretical CDF. Larger values suggest greater deviation from the target distribution.Comparison of the estimated KDEs for real and generated data can be performed both visually and through statistical measures, providing insights into whether the synthetic distribution adequately matches the real one.

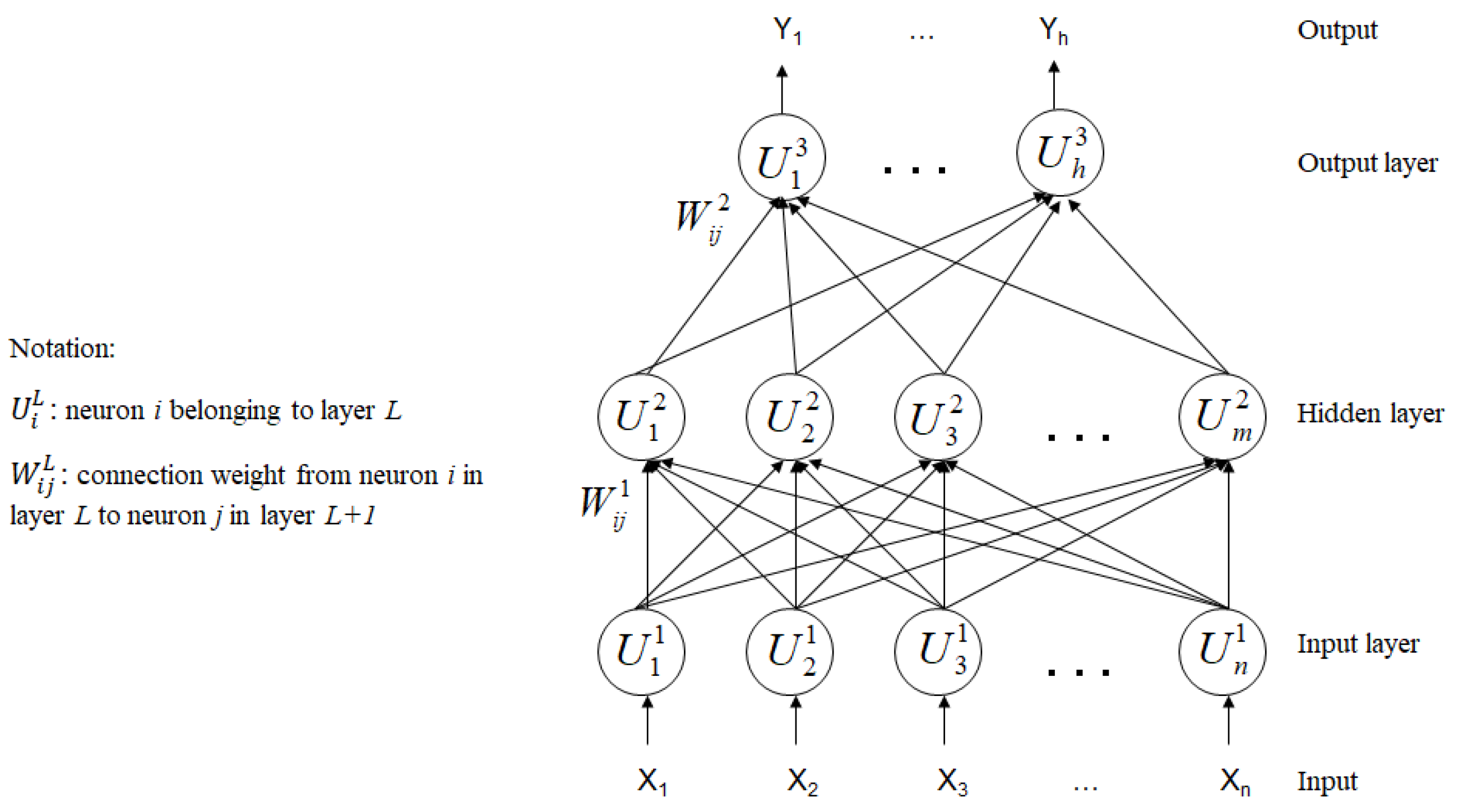

2.6. The Supervised Classification Algorithm

3. Results and Discussion

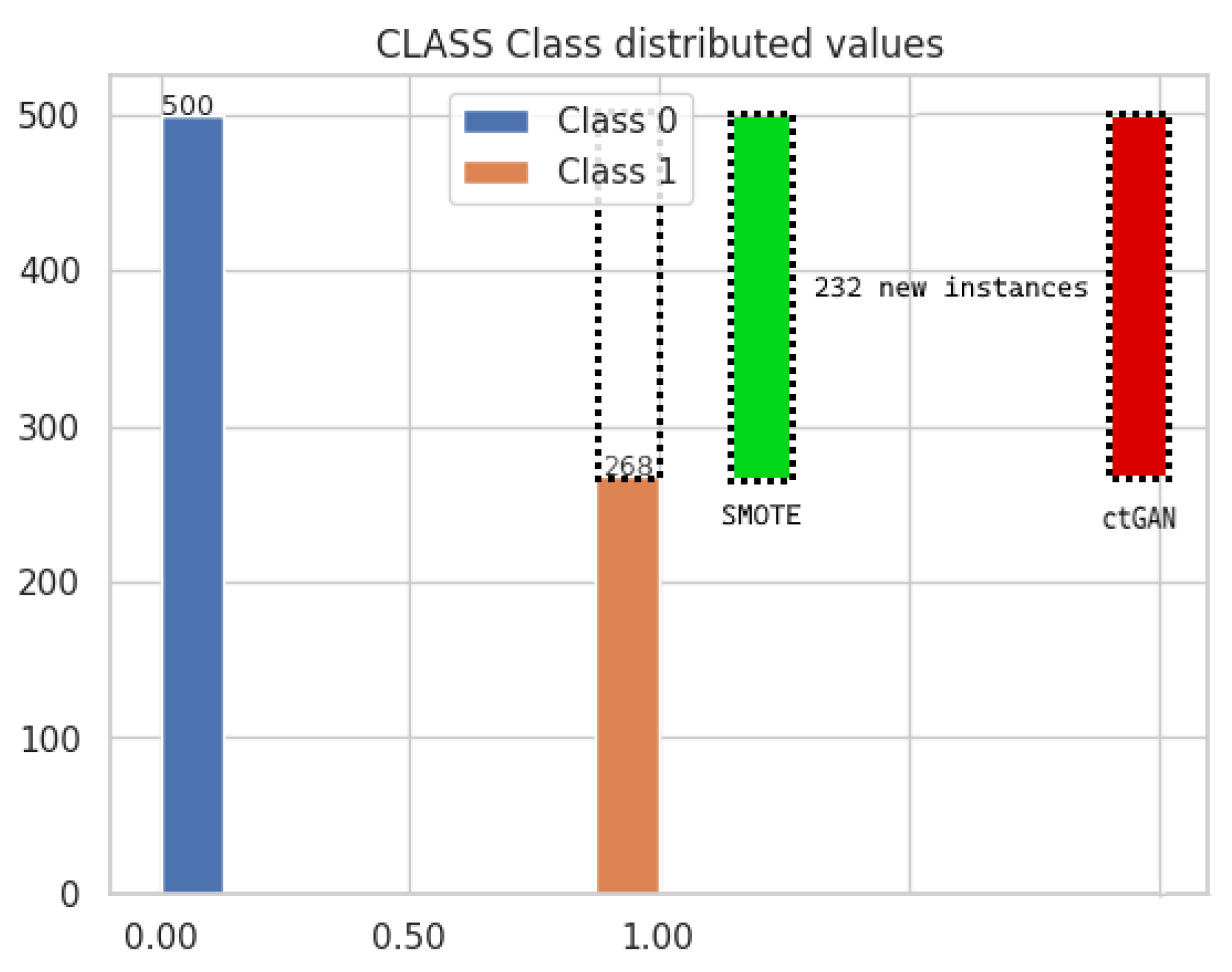

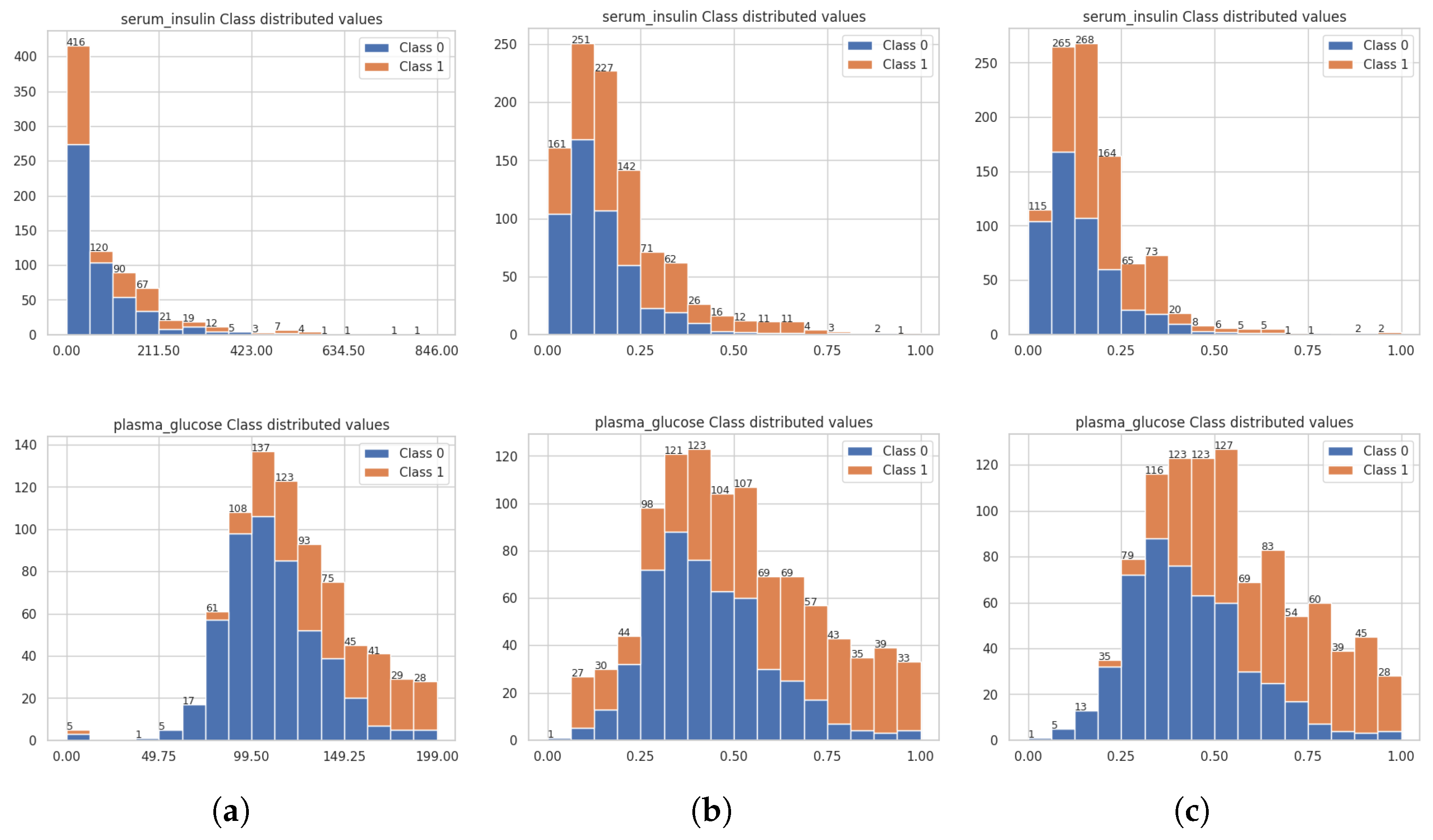

3.1. The Balanced Datasets from ctGAN and SMOTE Techniques

3.2. Assessing the Quality of the Balanced Datasets from ctGAN and SMOTE Techniques

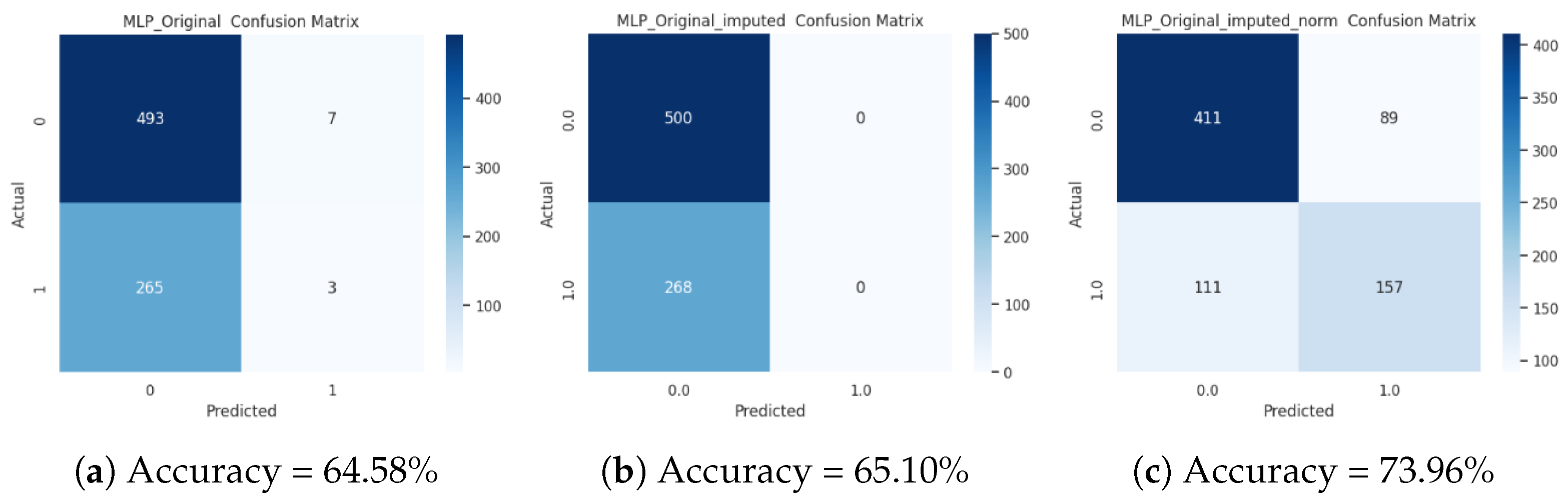

3.3. Analysis of the Accuracy of the Supervised Classification on the Original Dataset

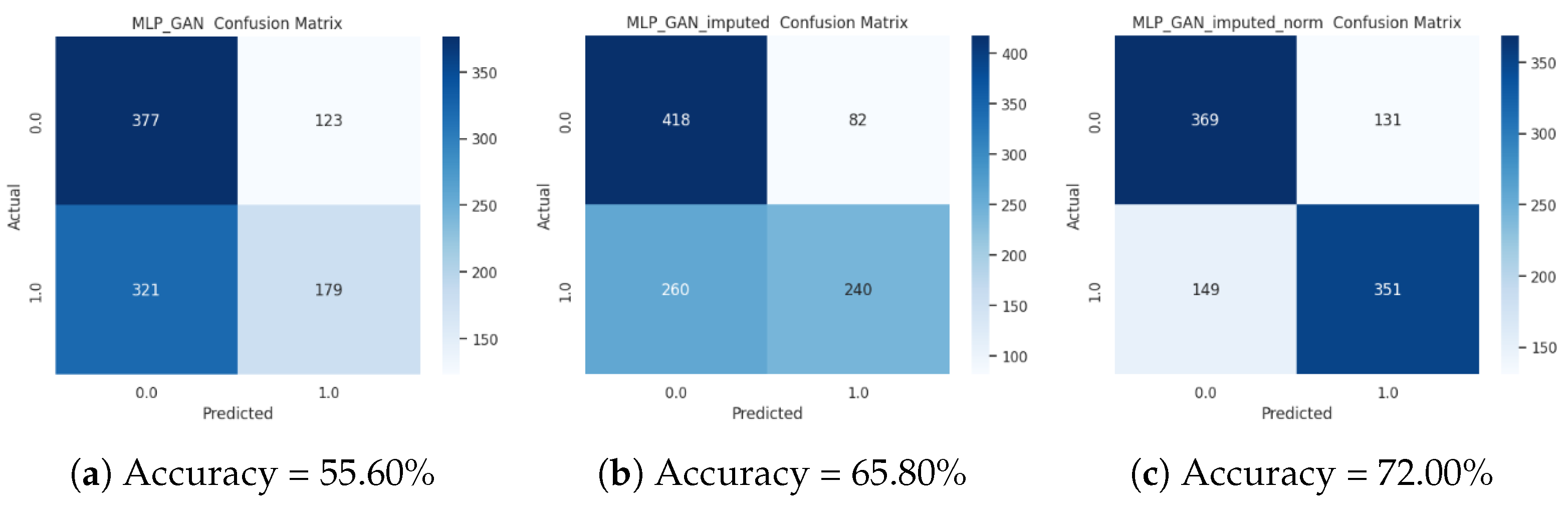

3.4. Analysis of the Accuracy of the Supervised Classification on the ctGAN-Augmented Dataset

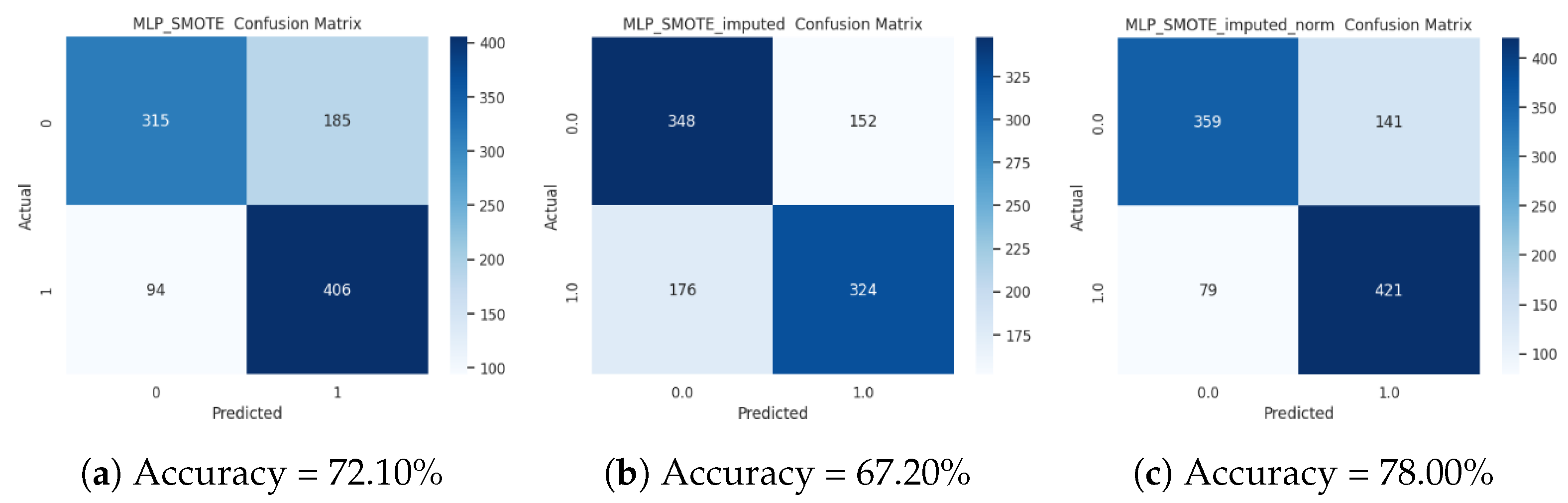

3.5. Analysis of the Accuracy of the Supervised Classification on the SMOTE-Augmented Dataset

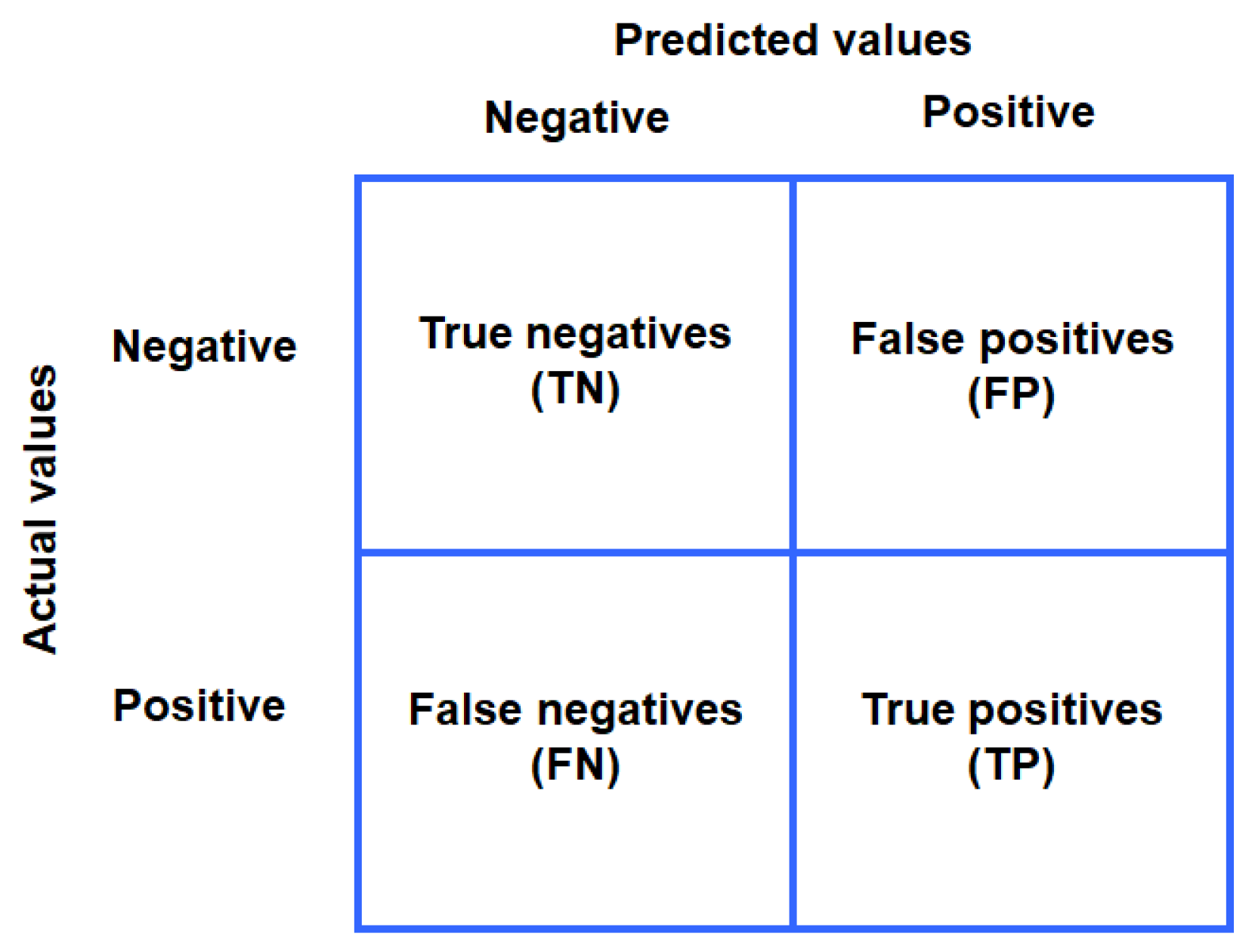

3.6. Performance Assessment Metrics for MLP on Original, SMOTE-Augmented, and ctGAN-Augmented Datasets

- Accuracy: overall proportion of correct predictions

- Precision: proportion of predicted positives that are correct

- Recall (Sensitivity): proportion of actual positives detected

- F1 Score: harmonic mean of precision and recall

3.7. Implications and Positioning Relative to Alternative Generative Approaches

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDF | Cummulative Distribution Function |

| ctGAN | Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Network |

| EMD | Earth Mover’s Distance or Wasserstein Distance |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler |

| KS | Kolmogorov–Smirnov |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| Probability Distribution Function | |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

References

- He, H.; Garcia, E. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabtah, F.; Hammoud, S.; Kamalov, F.; Gonsalves, A. Data imbalance in classification: Experimental evaluation. Inf. Sci. 2020, 513, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hsee, C.K.; Li, X. Prediction Biases: An Integrative Review. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Rawashdeh, J.; Abdullah, M. Machine Learning with Oversampling and Undersampling Techniques: Overview Study and Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai-Nghe, N.; Gantner, Z.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. Cost-sensitive learning methods for imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 July 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, M.; Feng, G.; Shi, X. A resampling ensemble algorithm for classification of imbalance problems. Neurocomputing 2014, 143, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Gatt, A.; Stamatescu, V.; McDonnell, M.D. Understanding Data Augmentation for Classification: When to Warp? In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA), Gold Coast, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Maqsood, M.; Nazir, F.; Khan, U.; Aadil, F.; Awan, K.M.; Mehmood, I.; Song, O.Y. A Data Augmentation-Based Framework to Handle Class Imbalance Problem for Alzheimer’s Stage Detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 115528–115539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ge, Z. Data Augmentation Classifier for Imbalanced Fault Classification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F. A Comprehensive Analysis of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) for handling class imbalance. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongvorachan, T.; He, S.; Bulut, O. A Comparison of Undersampling, Oversampling, and SMOTE Methods for Dealing with Imbalanced Classification in Educational Data Mining. Information 2023, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dablain, D.; Krawczyk, B. DeepSMOTE: Fusing Deep Learning and SMOTE for Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 6390–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gou, C.; Duan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, F.Y. Generative adversarial networks: Introduction and outlook. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative Adversarial Networks: An Overview. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Skoularidou, M.; Cuesta-Infante, A.; Veeramachaneni, K. Modeling Tabular data using Conditional GAN. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32, pp. 27517–27529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.; Careil, M.; Verbeek, J.; Drozdzal, M.; Soriano, A.R. Instance-Conditioned GAN. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 27517–27529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Gao, S. A flame image soft sensor for oxygen content prediction based on denoising diffusion probabilistic model. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2024, 255, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Luna, S.A.; Siddique, Z. Machine-Learning-Based Disease Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Rahman, S.; Zhou, J.; Kang, J.J. A Comprehensive Review on Machine Learning in Healthcare Industry: Classification, Restrictions, Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Khan, A.; Hossain, M.E.; Moni, M.A. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.; Atif, D.; Oliva, D.; Abraham, A.; Ventura, S. Handling imbalanced medical datasets: Review of a decade of research. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Huang, Y.; Hori, K.; Nishioji, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Kamaguchi, M.; Kano, M. Over- and Under-sampling Approach for Extremely Imbalanced and Small Minority Data Problem in Health Record Analysis. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Davis, D.N. Addressing the Class Imbalance Problem in Medical Datasets. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2013, 3, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Cheng, C.H. A multiple combined method for rebalancing medical data with class imbalances. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Pan, C.; Zhang, Y. An oversampling method for imbalanced data based on spatial distribution of minority samples SD-KMSMOTE. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, G.; Byeon, H. Searching for Optimal Oversampling to Process Imbalanced Data: Generative Adversarial Networks and Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, T.; Brijet, Z.; Subha, T.D. Imbalanced medical disease dataset classification using enhanced generative adversarial network. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 26, 1702–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wee, L.; Dekker, A.; Chen, Q.; Traverso, A. GAN-based one dimensional medical data augmentation. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 10481–10491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V.; Bailey, J.; Xu, Q.A.; Sun, Z. Pima Indians diabetes mellitus classification based on machine learning (ML) algorithms. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 16157–16173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar Ganesh, P.V.; Sripriya, P. A Comparative Review of Prediction Methods for Pima Indians Diabetes Dataset. In Computational Vision and Bio-Inspired Computing; Smys, S., Tavares, J.M.R.S., Balas, V.E., Iliyasu, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, R.; Khuntia, B. Analysis and Prediction Of Pima Indian Diabetes Dataset Using SDKNN Classifier Technique. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1070, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shen, D.; Nie, T.; Kou, Y.; Yin, N.; Han, X. A cluster-based oversampling algorithm combining SMOTE and k-means for imbalanced medical data. Inf. Sci. 2021, 572, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, A.; Chakraborty, C. Early and accurate prediction of diabetics based on FCBF feature selection and SMOTE. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 15, 4649–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagus, R.; Lusa, L. SMOTE for high-dimensional class-imbalanced data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Garcia, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, S. Impact of Nature of Medical Data on Machine and Deep Learning for Imbalanced Datasets: Clinical Validity of SMOTE Is Questionable. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.; Dorling, S. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchoun, H.; Amine, M.; Idrissi, J.; Ghanou, Y.; Ettaouil, M. Multilayer Perceptron: Architecture Optimization and Training. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2016, 4, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Number of Features | Number of Classes | Output Attributes | Number of Instances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pima Indians Diabetes | 8 | 2 | 1 | 768 |

| Class | Number of Instances | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 500 | 65.10 |

| 1 | 268 | 34.90 |

| Total | 768 | 100 |

| Feature | Dataset Type | Data Type | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Original | Imputed | 33.241 | 11.753 | 21.000 | 81.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 33.982 | 11.308 | 21.000 | 81.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 35.487 | 13.342 | 21.000 | 81.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.204 | 0.196 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.216 | 0.188 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.241 | 0.222 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| BMI | Original | Imputed | 32.433 | 6.890 | 18.200 | 67.100 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 33.017 | 6.646 | 18.200 | 67.100 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 33.222 | 7.384 | 18.200 | 67.100 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.291 | 0.141 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.304 | 0.138 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.307 | 0.151 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Diabetes Pedigree | Original | Imputed | 0.472 | 0.331 | 0.078 | 2.420 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 0.485 | 0.332 | 0.078 | 2.420 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 0.498 | 0.345 | 0.078 | 2.420 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.195 | 0.137 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.201 | 0.137 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.206 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Diastolic BP | Original | Imputed | 69.105 | 19.356 | 24.000 | 122.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 70.234 | 18.987 | 24.000 | 122.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 71.156 | 19.543 | 24.000 | 122.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.470 | 0.197 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.477 | 0.194 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.482 | 0.199 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Plasma Glucose | Original | Imputed | 121.586 | 30.542 | 44.000 | 199.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 126.071 | 31.211 | 44.000 | 199.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 125.141 | 32.203 | 44.000 | 199.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.500 | 0.197 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.530 | 0.202 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.523 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Serum Insulin | Original | Imputed | 79.799 | 115.176 | 14.000 | 846.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 82.156 | 112.543 | 14.000 | 846.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 83.234 | 118.987 | 14.000 | 846.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.078 | 0.138 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.081 | 0.135 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.082 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Skin Thickness | Original | Imputed | 20.536 | 15.952 | 7.000 | 99.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 21.234 | 16.123 | 7.000 | 99.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 21.987 | 16.543 | 7.000 | 99.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.147 | 0.173 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.152 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.157 | 0.180 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Times Pregnant | Original | Imputed | 3.845 | 3.370 | 0.000 | 17.000 |

| SMOTE | Imputed | 3.912 | 3.234 | 0.000 | 17.000 | |

| ctGAN | Imputed | 4.156 | 3.543 | 0.000 | 17.000 | |

| Original | Normalized | 0.226 | 0.198 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| SMOTE | Normalized | 0.230 | 0.190 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| ctGAN | Normalized | 0.245 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Metric | Comparison | Age | BMI | DP | Diast | PG | SI | ST | TP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | ctGAN-Imp | 2.249 | 0.797 | 0.036 | 1.773 | 3.560 | 21.124 | 0.690 | 0.349 |

| SMOTE-Imp | 0.988 | 0.626 | 0.011 | 0.607 | 4.489 | 10.929 | 0.855 | 0.267 | |

| ctGAN-Imp+Norm | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.007 | 0.021 | |

| SMOTE-Imp+Norm | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.029 | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.015 | |

| KS | ctGAN-Imp | 0.062 | 0.042 | 0.038 | 0.066 | 0.051 | 0.083 | 0.053 | 0.047 |

| SMOTE-Imp | 0.064 | 0.054 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.066 | 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.056 | |

| ctGAN-Imp+Norm | 0.062 | 0.042 | 0.038 | 0.068 | 0.052 | 0.085 | 0.044 | 0.047 | |

| SMOTE-Imp+Norm | 0.066 | 0.052 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.057 | 0.058 | |

| JS | ctGAN-Imp | 0.095 | 0.077 | 0.080 | 0.062 | 0.066 | 0.099 | 0.069 | 0.054 |

| SMOTE-Imp | 0.067 | 0.057 | 0.043 | 0.037 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.055 | 0.216 | |

| ctGAN-Imp+Norm | 0.095 | 0.077 | 0.080 | 0.066 | 0.067 | 0.101 | 0.039 | 0.054 | |

| SMOTE-Imp+Norm | 0.077 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.040 | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.057 | 0.222 | |

| KL | ctGAN-Imp | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.035 | 0.037 | 0.012 |

| SMOTE-Imp | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.138 | |

| ctGAN-Imp+Norm | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.035 | 0.006 | 0.012 | |

| SMOTE-Imp+Norm | 0.023 | 0.011 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.145 | |

| AD | ctGAN-Imp | 6.503 | 1.710 | 0.547 | 4.842 | 2.308 | 8.081 | 0.588 | 1.594 |

| SMOTE-Imp | 2.851 | 1.848 | −0.659 | −0.298 | 4.938 | 3.510 | 1.890 | 1.508 | |

| ctGAN-Imp+Norm | 6.503 | 1.774 | 0.547 | 4.988 | 2.346 | 8.238 | 0.264 | 1.594 | |

| SMOTE-Imp+Norm | 3.073 | 1.781 | −0.214 | 0.280 | 4.910 | 3.573 | 2.045 | 1.496 |

| Dataset | Accuracy (%) | F1 (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIMA imputed values | 65.1059 ± 0.0068 | 51.3468 ± 0.0087 | 42.3890 ± 0.0089 | 65.1059 ± 0.0068 |

| PIMA imputed GAN | 63.8000 ± 0.1382 | 60.7102 ± 0.1765 | 69.7921 ± 0.1655 | 63.8000 ± 0.1382 |

| PIMA imputed SMOTE | 66.9000 ± 0.0896 | 65.2231 ± 0.1131 | 70.4216 ± 0.0808 | 66.9000 ± 0.0896 |

| PIMA imputed GAN norm | 70.5000 ± 0.1593 | 68.8825 ± 0.2008 | 74.0516 ± 0.1228 | 70.5000 ± 0.1593 |

| PIMA imputed SMOTE norm | 77.3000 ± 0.1203 | 77.1173 ± 0.1213 | 78.2555 ± 0.1280 | 77.3000 ± 0.1203 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sagaceta-Mejía, A.R.; González-Pérez, P.P.; Fresán-Figueroa, J.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.E. Enhancing Predictive Accuracy in Medical Data Through Oversampling and Interpolation Techniques. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4032. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244032

Sagaceta-Mejía AR, González-Pérez PP, Fresán-Figueroa J, Sánchez-Gutiérrez ME. Enhancing Predictive Accuracy in Medical Data Through Oversampling and Interpolation Techniques. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4032. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSagaceta-Mejía, Alma Rocío, Pedro Pablo González-Pérez, Julián Fresán-Figueroa, and Máximo Eduardo Sánchez-Gutiérrez. 2025. "Enhancing Predictive Accuracy in Medical Data Through Oversampling and Interpolation Techniques" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4032. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244032

APA StyleSagaceta-Mejía, A. R., González-Pérez, P. P., Fresán-Figueroa, J., & Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M. E. (2025). Enhancing Predictive Accuracy in Medical Data Through Oversampling and Interpolation Techniques. Mathematics, 13(24), 4032. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244032