Abstract

Drilling tool attitude parameters are crucial for achieving precise directional drilling and trajectory control. Navigation systems based on redundant micro-electro-mechanical systems inertial measurement units (MEMS-IMU) significantly improve the reliability and accuracy of drilling tool attitude measurements. To achieve redundant arrangement of MEMS-IMUs, this paper proposes uniformly arranging MEMS-IMUs on a hollow hexagonal prism carrier, taking into account the actual structure of the drilling tool. However, under dynamic conditions, when updating drilling tool attitude using the strapdown inertial navigation system (SINS), the nonlinear errors of the MEMS-IMU accumulate over time, leading to distortion in the attitude calculation results. Therefore, this paper proposes a composite inertial measurement unit (CIMU) attitude measurement method. A virtual inertial measurement unit (VIMU) is generated through multi-IMU data fusion. Furthermore, the geometric constraints between each IMU and the VIMU, combined with Kalman filtering, are used to achieve real-time suppression of attitude errors, thereby improving the accuracy of the drilling tool attitude calculation results. Experimental results show that, compared with conventional data fusion methods, the CIMU algorithm reduces the overall drilling tool attitude error level by 40–70%.

MSC:

62M20

1. Introduction

The attitude of the drilling tool directly determines the bit orientation, trajectory control, and overall drilling efficiency. Therefore, enhancing the accuracy of attitude measurement is essential for ensuring both the safety and efficiency of the drilling process. With the advancement of directional drilling and measurement-while-drilling (MWD) technologies, inertial measurement units (IMU) have become indispensable for determining drilling tool orientation. Micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS)–based IMU offer advantages such as compact size, low power consumption, and ease of integration, making them particularly suitable for small-diameter drilling applications where space is limited [1,2]. Dynamic attitude measurement of the drilling tool typically employs a strapdown inertial navigation system (SINS). By continuously acquiring acceleration and angular velocity data output from the MEMS-IMU, the statically obtained attitude solution is input into the SINS, thereby enabling continuous attitude updates of the drilling tool during dynamic rotation. Ref. [3] derives an attitude update algorithm based on SINS. The basic idea is to use the attitude information of the previous moment and the angular velocity output by the gyroscope to calculate the attitude change at the current moment, thereby realizing continuous attitude update. This algorithm is highly sensitive to input data accuracy; however, downhole drilling is a strongly coupled dynamic process. Under complex drill bit-rock interactions and constantly changing operating parameters, the drilling tool and bottom hole assembly (BHA) are prone to phenomena such as axial bit bounce, torsional stick-slip, and lateral rotation [4,5]. These vibrations significantly affect the performance of the IMU and the accuracy of attitude measurements. Ref. [4] summarizes the latest advancements, control methods, and applications of drill string vibration research in deep and ultra-deep wells, focusing on analyzing vibration types, research trends, and future research directions. Ref. [6] used machine learning models such as radial basis functions (RBF) and support vector machines (SVM) to achieve automatic and accurate prediction of three types of downhole vibrations—axial, torsional, and lateral. Ref. [7] introduced a machine learning method combining model-independent regression techniques with Bayesian optimization extra trees (BO-ET) for real-time and accurate prediction of hazardous drill string slip events. Strong dynamic vibration during drilling can introduce high-frequency noise into IMU measurements, particularly affecting accelerometer and gyroscope signals. It further exacerbates the nonlinear coupling of MEMS-IMU errors. As a result, the long-term accuracy of SINS-based attitude determination is reduced. If unprocessed raw measurements are directly input into the SINS, errors will accumulate over time due to integration, causing the attitude calculation results to gradually deviate from the true value. Therefore, error determination and compensation of the MEMS-IMU output are essential before performing attitude updates. This paper focuses on how to suppress error divergence, thereby reducing the impact of these errors on the attitude calculation results.

MWD system based on a single MEMS-IMU is unstable and may not meet high-precision attitude requirements under long-term dynamic drilling conditions. This is because MEMS-IMUs have limited accuracy, and a single MEMS-IMU is easily damaged in the harsh downhole environment of high temperature and strong vibration. To mitigate the impact of errors from a single MEMS-IMU, this paper applies virtual inertial measurement unit (VIMU) technology. VIMU is a typical multi-sensor information fusion method [8]. It integrates multiple sensors of the same model and batch into a single unit and uses a data fusion algorithm to generate comprehensive measurement results, thereby improving measurement stability [9,10]. Ref. [11] proposes a noise variance estimation method based on the second-order cross-difference (SOMD) algorithm to address the problem of limited accuracy of a single IMU. It estimates the measurement noise variance of multiple IMUs in real time and uses weighted least squares (WLS) to generate the optimal VIMU in the observation domain. Ref. [12] proposes a fusion method that combines the outputs of multiple IMUs. First, it improves the random error modeling of the gyroscope output, amplifies the influence of angle random walk, and ignores the influence of rate random walk. Then, it uses the steady-state gain calculated by the Riccati Differential Equation (RDE) to reduce the computational burden of fusion filtering. Ref. [13] proposes a configuration scheme of redundant MEMS-IMUs for MWD. Through reliability theory and cost-effectiveness analysis, the optimal number of redundant MEMS-IMUs was determined to be six, and six MEMS-IMUs were arranged on a hollow hexagonal prism as a carrier. Then, the outputs of each IMU were fused by Kalman filtering to construct a VIMU. Based on this, Ref. [14] proposed a six-position calibration method for the sensor mounted on a hexagonal prism carrier tilted at 45°. Through an analysis of the sensor error characteristics and a comparison between measured and theoretical values, a compensation matrix was derived to correct installation errors.

Although the redundancy system improves the stability of attitude measurement, it still does not solve the problem that the various nonlinear errors of MEMS-IMUs such as zero-bias drift and scale factor error, exhibit dynamic coupling characteristics. These errors have little impact under static or slowly changing conditions but will continuously accumulate under dynamic conditions. At the same time, as the fusion dimension increases, these errors not only accumulate over time but also propagate through the SINS, leading to a significant decrease in attitude calculation accuracy. Existing studies have attempted to slow down error divergence by improving the fusion algorithm or introducing external references. Ref. [15] proposed and derived a unified extended Kalman filter (UEKF) for the fusion of multiple IMUs and provided a bias variance redistribution strategy to dynamically model the error of each sensor, thereby achieving self-correction of VIMU bias. Ref. [16] fused multiple physically separated but rigidly connected IMUs into a VIMU and positioned the reference coordinate system of the VIMU at the desired location. This simplified the lever-arm-related error in the propagation model and obtained more accurate results. Ref. [17] proposed an IMU error compensation method based on deep learning. It adopts a dynamic sensing window mechanism. Using deep learning techniques, it adaptively adjusts the processing range of input data. This enables modeling and compensation of IMU nonlinear errors during high-speed motion. In addition, nonlinear observer-based designs for low-cost attitude and heading reference system (AHRS), such as the immersion and invariance observer, have also been explored to improve attitude estimation robustness [18]. Although these methods enhance the accuracy of dynamic measurements, most existing algorithms still depend on statistical characteristics or external reference information for calibration. They do not possess a real-time self-correction capability derived from the system’s inherent geometric constraints. Therefore, this paper utilizes the system’s inherent geometric stability constraints to constrain errors, fundamentally enhancing the attitude measurement stability of the drilling tool under dynamic conditions.

Based on the hexagonal prism structural arrangement method of redundant MEMS-IMUs described in Ref. [13], this paper proposes the Composite Inertial Measurement Unit (CIMU) method. In this approach, six MEMS-IMUs are symmetrically arranged around the center of a hexagonal prism carrier to form a redundant MEMS, and the data from the six IMUs are fused to form the VIMU. The relative geometric constraint information between each IMU and the VIMU is then obtained and incorporated into the measurement equation for Kalman filtering to determine the attitude error at each moment. The CIMU method does not rely on any external reference information. Instead, it utilizes the inherent geometric stability of the system to constrain errors in real time. As a result, the stability of dynamic attitude measurement for the drilling tool is fundamentally enhanced. In this paper, Section 2 details the principle of the CIMU algorithm, Section 3 experimentally verifies the CIMU algorithm’s effectiveness in suppressing drilling tool attitude measurement errors.

2. Dynamic Attitude Measurement Method Based on CIMU

2.1. Six MEMS-IMUs Deployment Scheme

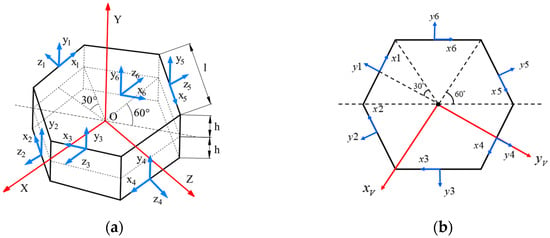

In MWD systems, MEMS-IMUs are typically encapsulated inside the drilling tool. Since the internal space of the drilling tool is primarily used for drilling fluid recirculation, the sensor arrangement must avoid affecting the hollow flow channels while maintaining assembly symmetry to prevent additional unbalanced torques. Therefore, the sensor arrangement not only needs good geometric symmetry but also should facilitate subsequent calibration and error compensation. Based on these requirements, this paper designs a redundant MEMS-IMUs arrangement scheme with a hollow hexagonal prism structure. This scheme constructs a hexagonal prism carrier structure outside the drilling tool’s central axis, evenly mounting six MEMS-IMUs on its six sides, forming a spatially evenly spaced and axially aligned arrangement, as shown in Figure 1. The sensor carrier is a compact, rigid, built-in component fixed to the drilling tool structure. It moves with the drilling tool as a rigid body and introduces no additional degrees of freedom. A Cartesian coordinate system is established with the prism’s center as the origin. The -axis is perpendicular to the prism’s sides, and the -axis is perpendicular to the -axis. The -axis direction of the IMUs is the same as the -axis direction of the Cartesian coordinate system. The -axis and -axis form certain angles with the -axis and -axis of the Cartesian coordinate system. This design preserves the flow channels for drilling fluid while geometrically achieving equidistant and equiangular distribution among the IMUs, facilitating the establishment of unified geometric constraints.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the layout of 6-MEMS-IMUs (a) Spatial diagram; (b) top view.

2.2. CIMU Algorithm Principle

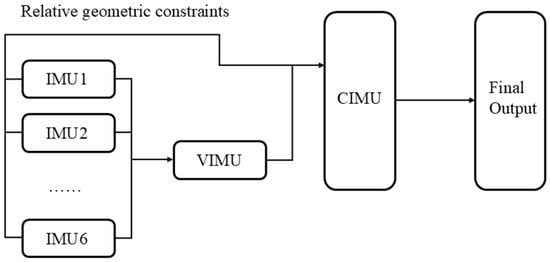

The CIMU data fusion process is shown in Figure 2. First, the six sets of IMU data are fused to form one set of VIMU data. Then, the VIMU and the six sets of IMUs each perform attitude calculations. The relative geometric constraint information between each IMU and the VIMU is used to improve the calculation accuracy. The relative geometric constraint information includes the relative attitude and relative velocity information. This information is then incorporated into a Kalman filter to dynamically constrain the real-time attitude error of the drilling tool. Finally, the optimal attitude solution of the drilling tool at the current moment is obtained using SINS.

Figure 2.

CIMU Data fusion process.

The CIMU algorithm is based on Kalman filter. It is a recursive optimal estimation algorithm, which includes a state equation and a measurement equation. Through these two equations, the theoretical state of the system and various measurement information are optimally integrated [19]. The Kalman filter equation for the drilling tool attitude measurement error is as follows.

where , represents the state at time , and represents the state at time . In the error state space, represents the VIMU’s attitude error vector, represents the VIMU’s inertial velocity error vector, and represents the VIMU’s inertial position error vector. represents the VIMU’s three-axis gyroscope bias vector, and represents the VIMU’s three-axis accelerometer bias vector. Since the CIMU augments the measurement model by introducing geometric-consistency constraints, the state-transition model remains identical to the VIMU. Therefore, the discrete process system noise covariance matrix is inherited from the VIMU and is determined by Allan-variance-identified random-walk parameters [13]. In this study, is assumed to be system white noise sequence and:

can be written in a block-diagonal form consistent with the 15-dimensional error-state vector:

Among them, and characterize the random-walk-driven evolution of the VIMU gyro and accelerometer biases, respectively, and are expressed as:

Here, , are obtained from the Allan-variance-identified rate and acceleration random-walk coefficients of the VIMU-equivalent gyro and accelerometer outputs and discretized according to the sampling period . The first three blocks reflect the propagation of sensor white noise through the SINS error dynamics and can be constructed following the standard SINS error model [3].

represents the attitude one-step transfer matrix, describing the theoretical change in each error state from time to time . It is obtained from the error equation of SINS [3].

Given multiple relative geometric constraints, the measurement vector, measurement matrix, and noise vector of the measurement equation are as follows.

In the measurement equation, is the attitude angle calculated by IMU , is the attitude angle calculated by the VIMU, is the relative attitude relationship between IMU and VIMU; is the velocity calculated by IMU , is the attitude angle calculated by the VIMU, and is the relative velocity relationship between IMU and VIMU.

is assumed to be measurement noise and:

Since the CIMU introduces constraint residuals as measurements, the measurement covariance can be written as

where

Here, and quantify the measurement noise of the IMU-VIMU attitude and velocity, respectively, for IMU . These values can be determined by analyzing the residual statistics after error compensation. Specifically, the carrier equipped with the IMU is placed in a stationary state, and the constraint residuals are recorded over a short period of time. The residual error state in a short-term stationary state can be considered negligible, therefore the constraint residuals primarily represent measurement noise.

As shown in Figure 1b, select the geometric center of the hexagonal prism as the reference point of VIMU, define the coordinate system of VIMU, and the coordinate system of each IMU is :

After each IMU is installed, its actual installation position can be obtained through measurement. Since CIMU’s geometric constraints are based on the nominal relative attitudes and positions of the six IMUs, installation misalignment will directly introduce structural deviations into the constraint residuals. When there are small angular installation errors, the acceleration measurement of a single IMU can be approximated as:

Here, represents the actual output of the accelerometer, is the true specific force vector, and is the small-angle mounting misalignment vector of the -th IMU. This equation shows that if there is a small angular deviation in the sensor carrier’s coordinate axes, the specific force, which was originally mainly distributed along one axis, will be projected onto other axes, thus affecting the attitude determination results. For CIMU, the more critical issue is that residual installation errors can cause the relative geometric relationship between the IMU and VIMU to become misaligned, weakening the effectiveness of the geometric constraints. Therefore, it is necessary to correct the installation errors using a compensation matrix before filtering. The method for determining the installation error compensation matrix is described in Ref. [14]. First, the carrier equipped with six sensors is tilted 45° around its own coordinate system -axis, and then rotated 60° around the -axis, successively obtaining six measurement attitudes with tool face angles of 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 300°.

For the -th sensor, measurements are taken once at each of the six attitude positions. The actual output of the accelerometer at the -th attitude is . The measured values and theoretical gravity projections for the six positions are as follows:

The installation error model for the accelerometer is as follows:

where is the installation error matrix, which combines the scale factor and non-orthogonal errors, and is expressed as:

represents the scale factors. Element represents the small angle error value of the installation. The compensation matrix represents the correction matrix that maps the measured value , which includes installation errors, back to the theoretical true value . This can be solved using the least squares method:

And then use the rotation matrix to describe the rigid body rotation from to :

where represents the measurement vector in the VIMU coordinate system, represents its corresponding measurement vector in the IMU coordinate system, and is the a priori fixed rotation matrix, which is determined by the relative attitude between the -th IMU coordinate system and the VIMU coordinate system . And is the projection of in the East-North-Up coordinate system.

The linear velocity relationship between any two points and on the hexagonal prism is expressed as:

where is the linear velocity of the IMU in its coordinate system, is the angular velocity of the VIMU in its coordinate system, and is the position vector between the IMU and the VIMU, pointing from the center of the VIMU coordinate system to the center of each IMU’s coordinate system. Therefore, the relative velocity is:

When six MEMS-IMUs arrays are fixed on a hollow hexagonal prism, ideally, the attitude and linear velocity between each IMU and VIMU should meet the following requirements.

Due to errors, the actual relative attitude and relative velocity calculated by each IMU and VIMU are not equal to and respectively. In this case, there is a measurement residual , which constitutes in the measurement equation.

In addition, in the measurement equation: is the measurement matrix, is the noise vector, and is composed of the misalignment angle error and velocity error of IMU .

The CIMU algorithm is derived by incorporating the relative geometric constraints between IMUs and VIMU into the Kalman filter. Using the error-state vector , the CIMU proceeds with a standard predict–update recursion.

Time update:

Here, is the posterior estimate at time , and is the prior prediction at time based on the information at time . is the current estimation error covariance, and is the prediction error covariance at time .

Measurement update with constraints:

Compared with the VIMU that relies solely on integrated inertial outputs, the CIMU preserves the same prediction model but introduces constraint-aware measurement updates, thereby limiting error accumulation and improving the stability and accuracy of drilling tool attitude estimation.

3. Experimental and Result Analysis

The feasibility of the algorithm was verified by designing a dynamic data fusion and attitude error solution experiment. The XNA100C IMU sensor of MICROINFINITY was used as the experimental object. The gyroscopic range was ±250°/s, the bias instability was 2°/h and the angular random walk was 0.2°/h. The accelerometer range was ±4 g, the zero bias instability was 50 μg and the random walk was 0.03 m/s/√h.

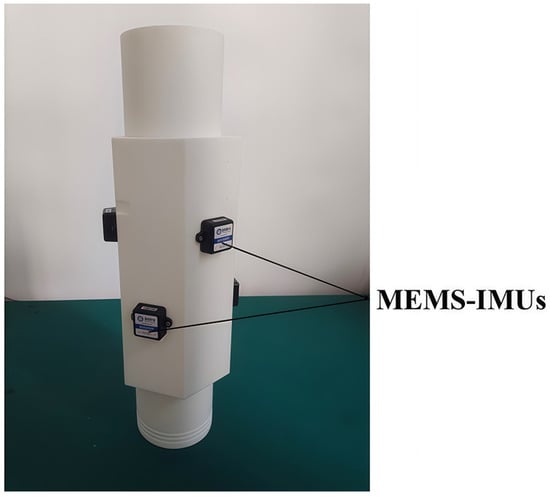

Figure 3 shows a physical image of the assembled 6-MEMS-IMUs.

Figure 3.

6-MEMS-IMUs Arrangement Structure.

The attitude of the drilling tool is described by three angles:

- (1)

- Inclination angle: It is the angle between the wellbore axis and the direction of gravity at the measuring point;

- (2)

- Tool face angle: It is the angle at which the tool face is located after the directional drilling tool has been lowered to the bottom of the well;

- (3)

- Azimuth angle: It is the angle between the projection of the carrier’s longitudinal axis onto the horizontal plane of the geographic coordinate system and the geographic north direction.

Therefore, this paper calculates these three angles using different methods to verify the effectiveness of the CIMU method.

As shown in Figure 4, the redundant MEMS-IMU system was securely mounted on a three-axis turntable, ensuring that the axis of the redundant system coincided with the -axis of the turntable. Both the control motor of the three-axis turntable and the redundant MEMS-IMU measurement unit were connected to the host computer, and communication was checked for normal operation.

Figure 4.

Experimental testing equipment (a) Three-axis rotary table (b) Physical construction of the carrier platform.

The turntable was controlled to maintain a certain inclination angle. After a 30 min preheating period, the host computer commanded the turntable to rotate, keeping the redundant system in a state of rotation about its own axis. This simulated drilling by keeping the azimuth and wellbore inclination angles constant while changing only the tool face angle. The data acquisition system was started simultaneously to record MEMS-IMU data for at least one hour. After data acquisition stopped, the data were imported into the analysis software.

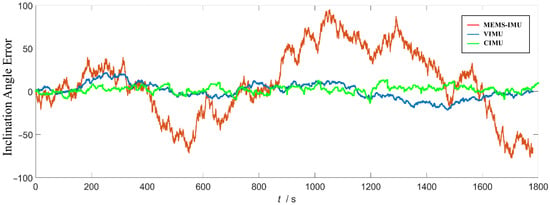

In this experiment, Fiber Optic Gyroscope (FOG) data was used as the true value. FOG is based on the Sagananu effect, and the zero-bias drift and random walk are much smaller than those of MEMS [20]. The attitude calculation results of single MEMS, VIMU and CIMU were compared and the errors were analyzed and compared. Figure 5 shows the inclination angle error calculation results.

Figure 5.

Comparison of inclination angle error calculation.

As shown in Figure 5, the inclination angle error calculated by a single MEMS device exhibits a significant low-frequency shift and large fluctuations over time, with the bias and random walk being amplified under dynamic conditions. The VIMU overall fluctuates slightly around the mean, but still exhibits slow drift during certain periods. The CIMU curve is closest to the zero line and exhibits minimal fluctuation, demonstrating a significant suppression effect on dynamic errors.

As shown in Table 1, the performance of the CIMU is verified by analyzing four parameters: the average value, peak-to-peak value, standard deviation and maximum value. The average value characterizes the system bias, the peak-to-peak value captures the overall fluctuation range under dynamic excitation, the standard deviation reflects the dispersion and stability, and the maximum value provides a conservative worst-case boundary. Together, these indicators fully demonstrate the advantages of the CIMU proposed in this paper in terms of improved stability and reduced error divergence. Compared with a single MEMS-IMU, CIMU reduced the average well inclination angle error by 90.8%, the standard deviation by 89.7%, the peak-to-peak value by 80.8%, and the maximum value by 85.1%. Compared to the VIMU, the CIMU reduces the standard deviation of the inclination error by 55.1%, the peak-to-peak value by 25.4%, and the maximum value by 36.7%. The CIMU’s mean inclination error is greater than the VIMU’s because the CIMU’s error is primarily distributed within the same half of the -axis, while the VIMU’s error is distributed across both the positive and negative -axis. Overall, the CIMU’s dynamic performance is superior to the VIMU.

Table 1.

Comparison of inclination angle error results.

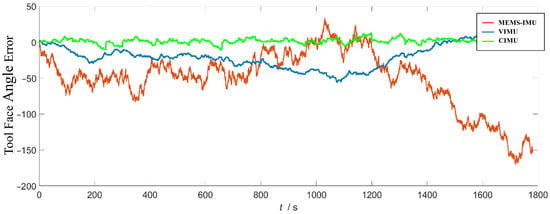

As shown in Figure 6, the attitude solution results of a single MEMS have large errors and poor stability. The tool face angle solution results of the VIMU are significantly improved compared to the MEMS-IMU, but there is still a certain amount of cumulative error during long-term operation. The tool face angle solution results of the CIMU have the highest stability and accuracy. In all key accuracy indicators, the CIMU has significant improvements compared to the single MEMS sensor, especially in reducing data discreteness and extreme errors.

Figure 6.

Comparison of tool face angle error calculation.

Table 2 shows that compared to a single MEMS-IMU, the CIMU reduces the mean tool face angle error by 95.3%, the standard deviation by 89.7%, the peak-to-peak value by 82.5%, and the maximum value by 89.1%. Compared to the VIMU, the CIMU reduces the mean tool face angle error by 87.96%, the standard deviation by 74.8%, the peak-to-peak value by 49.5%, and the maximum value by 67.1%. This demonstrates that the CIMU can effectively suppress error divergence and improve the measurement accuracy of the overall system.

Table 2.

Comparison of tool face angle error results.

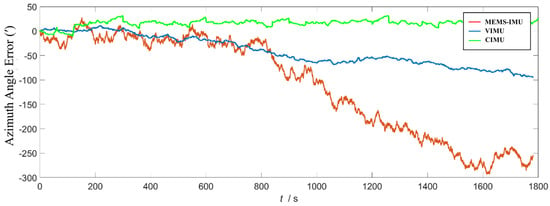

Figure 7 shows the azimuth angle solution results. The azimuth angle error of the single MEMS-IMU solution data fluctuates greatly during the experiment, and is prone to large cumulative errors over time, with a maximum value of up to 293.7′. The stability of the attitude solution results is poor; the attitude solution results of VIMU are more stable and accurate, but the errors are still serious; the CIMU solution results are significantly better than the other two algorithms, with stable solution results and small errors.

Figure 7.

Comparison of azimuth angle error calculation.

Table 3 shows that the attitude solution results from a single MEMS-IMU have large mean error and standard deviation. The VIMU’s error metrics are lower than those of a single MEMS-IMU, but its peak-to-peak value and maximum value are still relatively high. The CIMU’s error metrics are significantly lower than those of both the MEMS and VIMU. Compared to the VIMU, the CIMU’s mean azimuth error is reduced by 40.81%, the standard deviation by 62.39%, the peak-to-peak value by 51.36%, and the maximum value by 67.34%.

Table 3.

Comparison of azimuth angle error results.

Comparative analysis reveals that single MEMS attitude calculation results have larger errors and poorer stability, making them unsuitable for high-precision attitude measurement. VIMU attitude calculation results show significant improvement over MEMS, but some cumulative errors still exist over long-term operation. The proposed CIMU algorithm outperforms single MEMS-IMU and VIMUs in terms of stability and anti-divergence under dynamic conditions.

In summary, By integrating low-cost MEMS-IMUs array with geometric constraints, this paper achieves drilling tool attitude measurement performance close to that of a FOG in dynamic environments, balancing engineering-grade accuracy and cost-effectiveness.

4. Discussion

Dynamic measurement of drilling tool attitude relies on the SINS, and accurate results require accurate input data. Due to the inherent characteristics of MEMS-IMU, their nonlinear errors accumulate over time under dynamic conditions, leading to inaccurate output. Therefore, this paper focuses on suppressing the accumulation of real-time errors in MEMS-IMUs and proposes the CIMU method. The error suppression mechanism based on the internal geometric constraints of redundant systems proposed in this paper has broad applicability. It is particularly suitable for redundant systems with rigid connections or fixed spatial relationships between sensors. By embedding these constraints as prior known information into the fusion framework, self-calibration results based on the system’s inherent nature are obtained, mitigating the accumulation of long-term errors and achieving better dynamic measurement performance.

Subsequent research and improvements will focus on the following aspects:

- (1)

- All experiments in this paper were conducted in a laboratory using a three-axis turntable and no field tests were performed. The high temperature, high pressure, and strong vibration issues encountered in actual drilling operations were not considered. Further validation and improvements are needed in the future, incorporating field experiments.

- (2)

- Compared to single MEMS-IMU data processing methods, multi-MEMS-IMU data fusion methods require processing much larger databases. This paper primarily focuses on improving accuracy without considering the additional computation time and cost brought about by the increased data volume. Future research should explore how to balance accuracy and computational cost.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a CIMU algorithm by incorporating known, fixed, a priori geometric constraints into the data fusion of multiple MEMS-IMUs. This algorithm overcomes the problem of nonlinear errors accumulating over time during long-term MWD using low-cost MEMS-IMU. Specifically, six MEMS-IMUs are arranged along a hexagonal prism within the drilling tool, and the data from each IMU is fused to form a VIMU. A priori geometric constraints are then incorporated into the measurement equations of the Kalman filter. Since the geometric constraints are fixed, the measurement equations in the filter can constrain the divergence of the error state space in real time, thereby ensuring accurate and stable attitude calculation results even during long-term operation.

Experimental verification shows that compared to traditional methods, the CIMU algorithm reduces the standard deviation of azimuth error by 62.39%, the peak-to-peak value by 51.36%, and the maximum value by 67.34%. The standard deviation of inclination error is reduced by 55.1%, the peak-to-peak value by 25.4%, and the maximum error by 36.7%. The standard deviation of tool face error is reduced by 74.8%, the peak-to-peak value by 49.5%, and the maximum value by 67.1%.

This study successfully overcomes the inherent accuracy limitations of low-cost MEMS-IMU, significantly improving the accuracy of MWD during long-term operation, and providing a low-cost, highly reliable engineering solution for high-precision downhole attitude measurement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H. and L.W.; methodology, L.H. and Y.H.; software, L.H.; validation, L.W., Y.Z. and L.H.; formal analysis, L.H.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, L.W.; data curation, Y.Z. and Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and Y.H.; visualization, Y.Q.; supervision, Y.H.; project administration, L.W.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 42572293; Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resource Exploration-National Science and Technology Major Project, grant number: 2024ZD1003100.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maniatis, G. On the use of IMU (inertial measurement unit) sensors in geomorphology. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2021, 46, 2136–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’olio, F.; Natale, T.; Wang, Y.-C.; Hung, Y.-J. Miniaturization of interferometric optical gyroscopes: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 29948–29968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Weng, J. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Algorithm and Integrated Navigation Principle; Northwest University of Technology Press: Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Liu, S.; He, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, H. The state-of-the-art review on the drill pipe vibration. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Abid, K.; Srivastava, S.; Velasquez, A.F.B.; Teodoriu, C. A review of torsional vibration mitigation techniques using active control and machine learning strategies. Petroleum 2024, 10, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeldin, R.; Gamal, H.; Elkatatny, S. Detecting downhole vibrations through drilling horizontal sections: Machine learning study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahifar, B.; Hosseini, E. A new approach for real-time prediction of stick–slip vibrations enhancement using model agnostic and supervised machine learning: A case study of Norwegian continental shelf. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2023, 14, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, N. Sensor Data Fusion Analysis for Broad Applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M. A Lightweight and Accurate Localization Algorithm Using Multiple Inertial Measurement Units. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Zhu, T.; Peng, G.; Sun, F.; Dong, D. A Review on the Inertial Measurement Unit Array of Microelectromechanical Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, L. An Optimal Fusion Method of Multiple Inertial Measurement Units Based on Measurement Noise Variance Estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 23, 2693–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Chang, H.-L.; Yang, Y.; Qin, W.; Yuan, W.-Z. A novel Kalman filter for combining outputs of MEMS gyroscope array. Measurement 2012, 45, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Y. Redundant configuration method of MEMS sensors for bottom hole assembly attitude measurement. Micromachines 2024, 15, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Y. Installation Error Calibration Method for Redundant MEMS-IMU MWD. Micromachines 2025, 16, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libero, Y.; Itzik, K. A unified filter for fusion of multiple inertial measurement units. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.14524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Barfoot, T.D. Tunable Virtual IMU Frame by Weighted Averaging of Multiple Non-Collocated IMUs. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Wang, W.; Shi, Z.; Xie, L.; Chen, W.; Yan, Y.; Yin, E. Deep Learning-Based IMU Errors Compensation with Dynamic Receptive Field Mechanism. In Advances in Guidance, Navigation and Control; ICGNC 2024. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Yan, L., Duan, H., Deng, Y., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 1341. [Google Scholar]

- Keighobadi, J.; Hosseini-Pishrobat, M.; Faraji, J.; Langehbiz, M.N. Design and experimental evaluation of immersion and invariance observer for low-cost attitude-heading reference system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 7871–7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodarahmi, M.; Maihami, V. A Review on Kalman Filter Models. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, K.; Song, H.; Huang, Y.; Deng, G. From Micro-Optical to Quantum-Enhanced Gyroscopes: A Comprehensive Review. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, 2402065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).