Abstract

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a highly prevalent neurodevelopmental condition that is typically identified through behavioral assessments and subjective clinical reports. However, electroencephalography (EEG) offers a cost-effective and non-invasive alternative for capturing neural activity patterns closely associated with this disorder. Despite this potential, EEG-based ADHD classification remains challenged by overfitting, dependence on extensive preprocessing, and limited interpretability. Here, we propose a novel neural architecture that integrates transformer-based temporal attention with Gaussian mixture functional connectivity modeling and a cross-entropy loss regularized through -Rényi mutual information, termed T-GARNet. The multi-scale Gaussian kernel functional connectivity leverages parallel Gaussian kernels to identify complex spatial dependencies, which are further stabilized and regularized by the -Rényi term. This design enables direct modeling of long-range temporal dependencies from raw EEG while enhancing spatial interpretability and reducing feature redundancy. We evaluate T-GARNet on a publicly available ADHD EEG dataset using both leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) and stratified group k-fold cross-validation (SGKF-CV), where groups correspond to control and ADHD, and compare its performance against classical and modern state-of-the-art methods. Results show that T-GARNet achieves competitive or superior performance (82.10% accuracy), particularly under the more challenging SGKF-CV setting, while producing interpretable spatial attention patterns consistent with ADHD-related neurophysiological findings. These results underscore T-GARNet’s potential as a robust and explainable framework for objective EEG-based ADHD detection.

MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a highly prevalent neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity [1]. Globally, approximately 8% of children are affected [2], with continued symptomatology documented in up to two-thirds of diagnosed individuals into adulthood [3]. This persistence contributes to significant societal burdens, including reduced academic achievement and heightened demands on special education services [4]. Despite advances in diagnostic guidelines, current assessment procedures remain predominantly clinical, subjective, and highly dependent on trained practitioners, motivating a growing demand for objective, brain-based computational tools to support diagnosis [5].

Given ADHD’s strong association with brain function, neuroimaging techniques have gained attention as potential objective diagnostic aids. While functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been employed, it poses challenges for pediatric populations due to motion sensitivity and high cost [6]. In contrast, electroencephalography (EEG) offers a portable, affordable, and non-invasive method to measure brain activity with high temporal resolution. The advent of deep learning has catalyzed the use of EEG for ADHD detection by offering a means to analyze its complex signals [7]. Deep learning models can identify subtle, high-dimensional patterns in EEG data that may elude traditional analysis, promising objective, scalable, and low-cost tools for early diagnosis [8].

However, translating these advances into clinically deployable tools remains challenging due to several fundamental barriers. A primary limitation is the conventional reliance on rigid, multi-stage EEG preprocessing pipelines. Such pipelines typically include filtering, artifact removal, frequency-band decomposition, and handcrafted feature extraction [9]. While designed to suppress noise and enforce domain priors, these stages rely on strong a-priori assumptions about neural activity. This approach risks the irreversible removal of potentially valuable information, such as subtle cross-frequency couplings or non-linear transient dynamics, thereby limiting the model’s ability to discover novel biomarkers from the full richness of the raw signal [10]. Additionally, EEG signals exhibit substantial inter-subject variability, and ADHD itself presents heterogeneous neurocognitive profiles [11]. Models trained on limited or homogeneous cohorts frequently experience significant performance degradation when evaluated on new subjects or recording conditions, revealing vulnerability to domain shift and subject-specific noise [12]. This suggests that many existing approaches inadvertently learn dataset-specific artifacts rather than invariant neurophysiological structure [13].

In addition, a critical challenge is the tension between interpretability and expressive feature learning. Traditional machine learning approaches provide transparency but depend on predefined, handcrafted features that may overlook complex spatiotemporal mechanisms associated with ADHD [14]. Conversely, recent end-to-end deep learning models can learn rich representations directly from minimally filtered EEG [15], but often operate as opaque “black boxes.” This lack of neuroscientific interpretability complicates biomarker discovery, reduces clinical trust, and hinders the deployment of automated EEG-based ADHD assessment systems in medical settings [16].

Recently, EEG-based functional connectivity approaches have gained traction for their ability to capture coordinated neural activity across distributed brain regions [17]. Prior efforts have incorporated correlation matrices, coherence metrics, and graph theoretical measures into deep classifiers [18]. While promising, these methods frequently depend on exhaustive preprocessing or predefined frequency bands that constrain their representational flexibility [19]. Additionally, many existing works rely on evaluation strategies prone to information leakage, such as overlapping window segmentation without guaranteeing subject-level independence, limiting their clinical validity [20]. Moreover, traditional EEG classification methods for ADHD typically rely on handcrafted feature extraction in time, frequency, or time-frequency domains. Techniques such as wavelet transforms, power spectral density estimation, entropy measures, and fractal dimension analysis have been extensively applied to capture oscillatory dynamics and non-linear behavior in EEG signals [21,22]. Among these, Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) remain a widely adopted approach due to their ability to enhance discriminative spatial filters between classes [23,24]. Despite their interpretability and relatively low computational cost, these methods heavily depend on extensive preprocessing and strong domain-specific priors. Moreover, many studies have been limited by suboptimal validation strategies, including within-subject cross-validation or overlapping window schemes, which compromise clinical generalization [25]. These limitations highlight the need for subject-independent evaluation protocols, such as leave-subject-out cross-validation, and the development of more flexible, data-driven feature extraction techniques [26].

In response to these challenges, deep learning has emerged as a powerful alternative, capable of learning hierarchical representations directly from minimally processed EEG data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been widely applied by transforming EEG signals into time–frequency maps or connectivity matrices [27,28]. Among these, EEGNet has become a benchmark architecture due to its compact design and its use of depthwise separable temporal and spatial convolutions tailored for EEG analysis [29]. Building on this idea, several variants have been proposed from residual, fusion, and attention-based frameworks, which incorporate residual shortcuts, channel-wise attention, or frequency-adaptive modules to enhance expressive power [30,31].

Beyond EEGNet, earlier yet influential convolutional models such as ShallowConvNet and DeepConvNet [32] have demonstrated the effectiveness of hierarchical temporal–spatial filtering, with ShallowConvNet emphasizing band-power extraction and DeepConvNet enabling deeper abstraction of spectral–temporal patterns. More recent architectures adopt hybrid or modular designs—such as Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)-based models, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), RNN-CNN hybrids, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) for functional connectivity, and spectral–temporal attention networks—to better capture long-range temporal dependencies, cross-channel interactions, and subject-specific variability [33,34,35]. However, despite their progress, many of these architectures remain limited in interpretability and continue to struggle with overfitting when trained on small or heterogeneous EEG datasets [36].

In turn, transformers have recently demonstrated strong performance in EEG analysis due to their ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies and learn attention maps interpretable as channel relevance patterns [37]. Nevertheless, their high modeling capacity also makes them particularly susceptible to overfitting in low-sample, high-variance EEG settings, where they may inadvertently learn subject-specific instead of neurophysiologically meaningful structure [38,39]. Meanwhile, information-theoretic regularization has shown strong potential to promote disentangled and complementary feature learning, particularly through Rényi entropy-based formulations that offer robust sensitivity to higher-order statistical structure [40]. Yet, this powerful mathematical framework remains underexplored in clinical EEG modeling.

To address these challenges, we introduce T-GARNet, a Transformer and Gaussian mixture connectivity network with -Rényi regularization for EEG-based ADHD detection. T-GARNet jointly models temporal dynamics via a Transformer encoder and spatial structure via a Gaussian mixture connectivity module that learns latent interaction kernels across EEG channels without requiring predefined connectivity measures [41]. To further ensure the representation diversity essential for interpretability and generalization, we incorporate a mutual-information penalty based on -Rényi entropy that encourages complementary feature extraction across attention heads and connectivity kernels [42]. This principled framework enables direct learning from minimally preprocessed EEG, supports neuroscientific interpretability, and promotes robust out-of-distribution generalization. Namely, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

- –

- We introduce a novel deep learning architecture that unifies Transformer-based temporal attention with a multi-scale Gaussian mixture connectivity module, enabling the extraction of spatiotemporal EEG representations directly from raw signals and eliminating the need for handcrafted features or predefined connectivity assumptions.

- –

- We introduce an -Rényi mutual-information regularizer that enforces representation diversity across attention and connectivity components, reducing redundancy and supporting interpretability.

- –

- We design a multi-layer interpretability framework that integrates attention-based channel relevance, Gaussian kernel-derived class activation maps, and structured ablation analysis to uncover coherent neurophysiological patterns linked to ADHD and to provide transparent insights into the model’s spatiotemporal decision mechanisms.

- –

- We conduct extensive experiments using subject-group cross-validation and comparative baselines, demonstrating competitive performance and strong interpretability on a pediatric EEG ADHD dataset.

Overall, T-GARNet offers a reliable and interpretable framework for EEG-based ADHD detection by integrating information-theoretic regularization, connectivity-aware modeling, and explainable attention mechanisms. Clinically, its ability to learn meaningful biomarkers directly from minimally processed EEG reduces reliance on subjective assessments, supports earlier identification of attentional difficulties, and enables scalable, low-cost pediatric screening. By avoiding handcrafted features and emphasizing automatically learned spatiotemporal patterns, the approach can complement clinical judgment and promote more objective and reproducible ADHD evaluation [43].

2. Materials and Methods

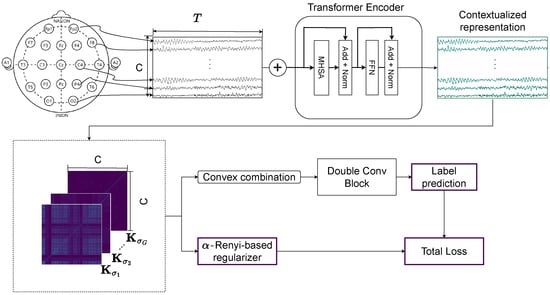

The proposed T-GARNet framework integrates mathematical principles from kernel information theory with modern deep sequence modeling to extract interpretable spatiotemporal connectivity patterns from EEG signals. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the architecture, highlighting its two main components: (i) a lightweight Transformer encoder for temporal representation learning, implemented with a single encoder block and two attention heads, and (ii) a multi-scale Gaussian connectivity module composed of three kernels enforcing complementary spatial structure via -Rényi regularization. This section presents the theoretical foundations, followed by a detailed description of each architectural element and the optimization scheme.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed T-GARNet model. Raw EEG segments are processed by a Transformer Encoder for temporal feature learning, followed by a Multi-Scale Gaussian connectivity module that generates multiple kernel-based connectivity matrices. These are refined via convolutional layers. The final objective combines binary cross-entropy with an -Rényi mutual-information regularizer to enforce non-redundant connectivity features.

2.1. Kernel Methods and Functional Mapping

Kernel methods provide a powerful strategy for capturing non-linear relationships by implicitly mapping data into a high-dimensional reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). Rather than operating directly on raw observations, kernels make it possible to evaluate similarity in a transformed space where complex dependencies behave more linearly, while avoiding the explicit construction of such a space.

Let denote the input domain. A kernel function defines an inner product between and in an RKHS via

where is an implicit feature map [44]. This formulation allows one to compare samples through pairwise similarity measures without explicitly computing the (potentially infinite-dimensional) representation .

Gaussian kernels are particularly useful because they yield smooth similarity profiles and possess universal approximation capability [45]. Their functional form is given by

where controls the sensitivity of the kernel to local or global structure. Intuitively, points that are close in input space produce similarity values near one, while distant points yield values approaching zero. Moreover, since the Fourier transform of a Gaussian is also Gaussian, this kernel implicitly encodes smooth spectral behavior—an advantageous property for neurophysiological signals whose frequency composition is informative [46].

2.2. Matrix-Based -Rényi Entropy and Mutual Information

Entropy-based measures provide a way to quantify uncertainty or information content in observed data. Let X be a continuous random variable defined on with probability density function (PDF) . The -Rényi entropy for and is defined as

which increases when the distribution becomes more diffuse, and decreases when samples are concentrated. Since is generally unknown in high-dimensional settings, it may be approximated using kernel density estimation (KDE) from N i.i.d. samples :

where denotes a Gaussian kernel as in (2). This nonparametric density estimator allows entropy to be approximated through pairwise sample similarities.

For , Rényi entropy reduces to quadratic entropy, closely related to the Information Potential (IP) [47]:

meaning that higher values of IP reflect sets of samples that are more similar.

Let be the Gram matrix with entries . Then,

where is the all-ones vector. Now, define a normalized matrix . If denote its eigenvalues, the matrix-based -Rényi entropy [48] is

which provides a tractable way to quantify sample uncertainty directly from kernel matrices.

For the quadratic case , a numerically stable formulation is

highlighting that the entropy depends on the energy of the normalized kernel matrix.

To extend this idea to dependencies between variables, let X and Y denote random variables with kernel matrices and . Their joint kernel is computed via the Hadamard product:

and its trace-normalized version yields the joint entropy:

The matrix-based mutual information (MI) follows:

which increases when the kernel representations of X and Y share structure and decreases when they contain complementary information.

This formulation offers three advantages crucial for EEG modeling:

- –

- Nonparametric: no assumptions on the underlying EEG distribution are required.

- –

- Differentiable: enables end-to-end learning via backpropagation.

- –

- Redundancy control: penalizes redundant similarity structures, encouraging disentangled connectivity patterns across spatial scales.

Of note, the selection of arises from its strong theoretical grounding and computational advantages [42]. In the quadratic case, matrix-based Rényi entropy reduces to a closed-form expression based on the Frobenius norm of the normalized Gram matrix, avoiding the unstable matrix powers required for arbitrary . This yields more reliable gradients during training and connects directly to the well-established IP, as in Equation (5), offering an interpretable measure of similarity structure.

2.3. Multi-Scale Gaussian Kernel Connectivity

Functional connectivity in EEG reflects coordinated neural activity across cortical regions. To represent such interactions in a principled and data-driven manner, we construct kernel-based similarity matrices between channels. This formulation is grounded in the spectral properties of stationary stochastic processes and their correspondence with positive-definite kernels.

Let be a wide-sense stationary process with autocorrelation function

where denotes the temporal frequency, is an absolutely continuous spectral distribution, and denotes its power spectral density [49]. This identity indicates that second-order temporal statistics can be interpreted through the frequency content of the signal.

A key theoretical grounding comes from Bochner’s theorem, which states that a continuous function is stationary and positive-definite if and only if it admits a spectral representation:

for some finite, non-negative measure . Hence, valid kernels correspond to valid spectral distributions. In practical terms, a kernel implicitly defines an interaction profile in the frequency domain, making kernel matrices a natural surrogate for neurophysiological connectivity patterns [41].

For multichannel EEG signals , this interpretation extends to cross-spectral similarity:

where denotes the cross-spectral density and is its cumulative distribution. Thus, similarity between channels reflects how their frequency components co-vary.

Direct estimation of from EEG is challenging due to noise, limited data, and nonstationarity. Instead, a widely used surrogate is to approximate the spectral distribution with a Gaussian function, as in (2). The bandwidth regulates the scale of interaction: smaller values emphasize local, fine-grained connectivity, while larger values capture broader distributed synchrony across the cortex.

To model the inherently multi-scale nature of brain networks, we construct a convex combination of G Gaussian kernels:

where is the kernel matrix associated with scale and are learnable mixture coefficients. This mixture yields a multi-resolution connectivity representation while preserving kernel validity and normalization.

Within the proposed T-GARNet architecture, these kernel matrices provide structured spatial representations of EEG that complement the temporal dependencies learned by the Transformer encoder. Each kernel captures connectivity at a distinct cortical scale, and the convex combination enables adaptive integration of local and global synchrony patterns relevant to ADHD. The resulting connectivity maps are refined through convolutional layers, promoting hierarchical interaction among spatial features. In conjunction with the -Rényi regularization term, this framework encourages complementary connectivity features across scales, improving interpretability and robustness.

2.4. Transformer and Multi-Kernel Gaussian Connectivity Network with -Rényi Regularization

Let denote an EEG trial with C channels and T temporal samples. Each segment is first transposed to , treating each time step as a token with a C-dimensional feature representation. This tokenization aligns with Transformer-based modeling of sequential biomedical signals, enabling the extraction of long-range temporal dependencies while preserving spatial structure across electrodes.

The token sequence is processed by a single Transformer encoder block composed of multi-head self-attention (MHSA) and a positionwise feedforward network. For each attention head , the input matrix is linearly projected into Queries (), Keys (), and Values ():

where the weight matrices and are learnable parameters. In the canonical setting, . These projections allow each head to extract distinct relevance patterns between channels.

The attention output of head h is computed as

where the softmax operator yields normalized interaction weights across time. The MHSA operation concatenates all heads and projects them back to :

where is a learned output projection matrix. This mechanism learns scale-adaptive temporal dependencies across EEG tokens, while the resulting attention maps provide physiologically interpretable channel relevance cues.

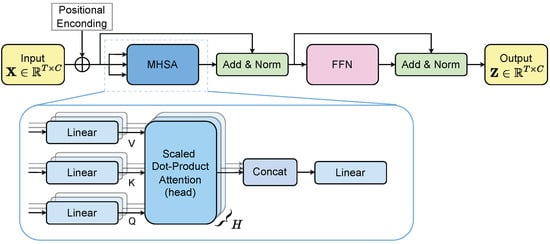

The MHSA output is passed through a positionwise MLP with residual connections and layer normalization, following standard Transformer design (Figure 2) [50]. The resulting representation encodes temporal dependencies enriched by channel-wise contributions. In our implementation, we employ a lightweight configuration consisting of a single encoder block with two attention heads (). Preliminary architectural sweeps indicated that this was the smallest configuration achieving stable generalization while avoiding performance degradation observed with deeper stacks or larger head counts [51].

Figure 2.

Transformer encoder main pipeline for EEG-based feature extraction.

The temporal representation is transposed to so that each row corresponds to a channel-level feature vector. From this representation, we compute a bank of G Gaussian kernel connectivity matrices that integrate information across resolutions (see Equation (15)). Here, the coefficients act as trainable attention-like weights that emphasize the most informative scales.

The matrix is refined through two convolution–normalization blocks:

where each convolution enhances localized EEG interactions. The resulting representation is vectorized and classified via a dense layer:

where denotes the predicted probabilities for ADHD and control classes.

Our T-GARNet loss combines normalized binary cross-entropy with an information–theoretic term that penalizes redundancy across the G multi-scale connectivity matrices. The normalized binary cross-entropy is given by

where is the batch size, the ground-truth label, and the predicted probability.

To promote non-redundant spatial structure, an -Rényi mutual-information term (see Equation (11)) across kernel scales is employed. Let be the Gaussian connectivity matrices and their trace-normalized versions. Denoting by the corresponding matrix-based entropy, our MI loss is

which is minimized when the joint entropy approaches the sum of marginal entropies, encouraging complementary information across scales. The total loss is thus

The MI formulation in Equation (23) benefits EEG modeling in three ways. First, because it is computed directly from kernel similarities, it is fully nonparametric and does not impose distributional assumptions on EEG signals. Second, all operations are differentiable, allowing the regularizer to be integrated seamlessly into end-to-end training. Third, MI provides redundancy control: when multi-scale kernels encode overlapping connectivity patterns, their joint entropy increases more slowly than the sum of the individual entropies, resulting in a higher MI penalty. This encourages each kernel to capture complementary spatial structure. In this setting, the -Rényi entropy acts as an information-theoretic regularizer by penalizing redundant similarity patterns and promoting diverse, interpretable connectivity representations.

3. Experimental Set-Up

3.1. Tested ADHD Dataset

This study uses an EEG dataset publicly available on IEEE DataPort [52], comprising recordings from 121 children aged 7 to 12 years, including 61 with ADHD and 60 healthy controls (accessed on 1 July 2025). ADHD diagnoses were made by an experienced psychiatrist following DSM-IV criteria, and participants had received Ritalin treatment for no longer than six months. Control subjects had no history of psychiatric or neurological conditions. A summary of participant demographics and EEG acquisition parameters is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the EEG dataset used for ADHD classification.

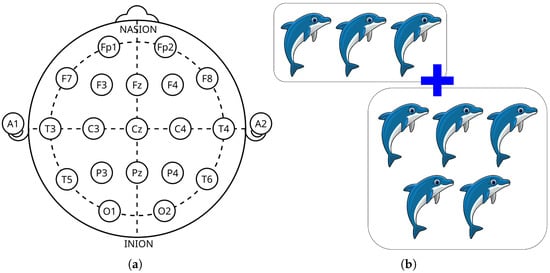

EEG data were recorded using the 10–20 system with 19 electrodes and referenced to A1 and A2 on the earlobes (see Figure 3a), sampled at 128 Hz. The recording protocol was designed to assess visual attention, a cognitive function often impaired in children with ADHD. During the task, children viewed cartoon images and were asked to count the number of characters (randomly 5–16 per image). Stimuli were presented in rapid succession immediately following each response, making total recording duration dependent on individual response speed (see Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

EEG acquisition setup and cognitive task used during the experiment. (a) Standard 10–20 system with 19 channels for EEG data acquisition. (b) Example of the visual stimuli shown to children during EEG recording.

To ensure class balance prior to model training, one ADHD subject was randomly removed from the dataset, resulting in a final sample of 120 participants (60 control and 60 ADHD). After balancing, all subsequent analyses proceeded as described. To minimize preprocessing bias and evaluate the model’s capacity to learn directly from raw electrophysiological structure, EEG signals were fed to the network without artifact removal, filtering, or spectral band decomposition. This design enables the model to operate on minimally processed neural activity, avoiding conventional assumptions about spectral relevance and reducing the risk of discarding physiologically meaningful dynamics. Also, following standard practice in EEG-based classification [19], recordings were segmented into 4 s epochs (512 samples at 128 Hz) with a 50% overlap. Consecutive windows therefore begin every 2 s, yielding dense temporal sampling while preserving temporal independence assumptions (see Figure 4). This segmentation produced the following: Control group: 3657 segments (mean per subject); ADHD group: 4622 segments (mean per subject). Moreover, each epoch was treated as an independent training instance, but subject identity was preserved and never mixed across folds, ensuring strict subject-wise separation in all evaluation pipelines.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the EEG preprocessing strategy. Raw continuous recordings are partitioned into 4 s windows (512 samples at 128 Hz) with 50% overlap, producing partially overlapping temporal segments. This segmentation preserves transient neurophysiological dynamics while increasing the number of training instances and helping stabilize learning under subject-independent evaluation.

3.2. Assessment, Model Comparison, and Training Details

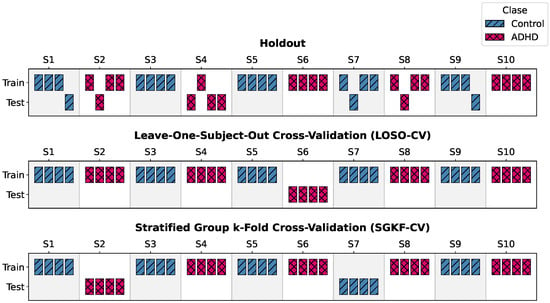

To assess generalization under rigorous subject-independent conditions, two complementary validation schemes were implemented. Figure 5 presents a simplified illustrative example using a hypothetical cohort of 10 subjects, highlighting how Holdout, LOSO-CV, and SGKF-CV differ in the way subjects are split between training and testing. This visualization helps clarify the allocation strategy conceptually, before scaling it to the full cohort of 120 participants used in our experiments.

Figure 5.

Illustration of validation schemes using an example cohort of 10 subjects. Unlike naive segment-based splits, LOSO-CV and SGKF-CV strictly isolate subject identities across folds, ensuring reliable generalization estimates.

- –

- Leave-One-Subject-Out Cross-Validation (LOSO-CV). At each iteration, data from a single subject were held out exclusively for testing, while the remaining subjects formed the training set. This is repeated N times so that each participant serves as the test set once.

- –

- Stratified Group k-Fold Cross-Validation (SGKF-CV). A subject-wise stratified scheme was employed. This choice follows established recommendations indicating that five folds provide a good trade-off between estimator variance, statistical reliability, and computational cost in supervised learning settings [53,54]. In each fold, 24 subjects (12 ADHD, 12 controls) were reserved for testing and the remaining 96 formed the training set. Stratification preserved class balance across folds.

In both protocols, no temporal or subject-level data leakage occurred. Segments from the same subject never appeared in both training and testing sets.

T-GARNet was benchmarked against five baseline models selected to represent complementary design paradigms in EEG learning. The objective was to position the proposed architecture within a broad methodological landscape, spanning traditional machine learning, compact convolutional models, recurrent hybrids, and Transformer-based systems. The reference models included the following:

- –

- CNN-based Architectures (ShallowConvNet [32], EEGNet [29]): These models represent compact, efficient, and widely adopted CNNs designed specifically for end-to-end EEG processing. They serve as a baseline to evaluate the performance of standard deep learning approaches that do not explicitly model connectivity or long-range temporal dependencies with attention.

- –

- Hybrid Architecture (CNN–LSTM [33]): This model combines CNNs with Recurrent Neural Networks (LSTMs). It provides a point of comparison for evaluating T-GARNet’s Transformer-based approach against more traditional methods for modeling temporal sequences.

- –

- Attention-based Architecture (Multi-Stream Transformer [19]): This model also uses Transformers, but processes spectral, spatial, and temporal streams independently. It serves as a critical baseline to evaluate the benefits of T-GARNet’s integrated architecture, where temporal attention and spatial connectivity modeling are directly linked.

- –

- Classical Machine Learning Pipeline (ANOVA–PCA SVM [38]): This model represents a traditional, non-end-to-end approach involving explicit feature engineering, selection, and classification. It provides a baseline to quantify the performance gains achieved by deep learning methodologies.

- –

- Integrative Deep Learning Architecture (IM-CBGT [55]): This model fuses CNN, BiLSTM, and GRU-Transformer branches into a unified classifier, enabling simultaneous learning of spatial features, long-range temporal dependencies, and attention-driven sequence interactions. It provides a reference point to assess the benefit of multi-path integration over single-stream CNNs, hybrid CNN–RNN models, or purely Transformer-based pipelines.

All networks were trained and evaluated using identical cross-validation folds to enable direct comparison. In keeping with the original methodological prescriptions, preprocessing was applied only to the models that explicitly require it (ANOVA–PCA SVM and Multi-Stream Transformer). Deep learning models that support raw EEG input, including T-GARNet, were evaluated on minimally processed signals to preserve comparability in end-to-end settings. Table 2 summarizes the architectural components, parameter counts, and the model ability to operate directly on raw EEG.

Table 2.

Comparison of architectural characteristics across baseline models and the proposed T-GARNet. The table contrasts modeling strategies, showing which approaches incorporate convolutional processing, recurrent dynamics, attention mechanisms, or connectivity learning. T-GARNet uniquely combines raw EEG processing, attention-based temporal modeling, multi-scale kernel connectivity, and information-theoretic regularization, while remaining highly parameter-efficient: it is the second-most compact trainable model in the comparison despite integrating the richest set of modeling components.

Deep learning models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 16 and a fixed training horizon of 100 epochs. For all baseline and comparative models, optimization was performed by minimizing the categorical cross-entropy loss. In the proposed T-GARNet architecture, a normalized cross-entropy formulation was employed and augmented with an -Rényi mutual-information regularization term, yielding the composite objective defined in Equation (23). The regularization weight was not treated as a fixed hyperparameter; instead, it was gradually increased throughout training, starting from zero and asymptotically approaching its maximum value () as the number of epochs increased. This progressive weighting strategy allows the model to prioritize discriminative learning during early optimization stages, while increasingly enforcing information-theoretic regularization as training proceeds.

All experiments were executed in a cloud-based Kaggle environment using Python 3.11.11 and TensorFlow 2.18.0. The hardware configuration included an Intel Xeon CPU @ 2.00 GHz (4 logical cores), 31 GB RAM, and two NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPUs with 15 GB VRAM each, operating under a 64-bit Ubuntu-based system. GPU acceleration was enabled through CUDA 12.6 and NVIDIA driver version 560.35.03. For reproducibility, all source code, scripts, and configuration files are publicly available at https://github.com/dannasalazar11/Msc_thesis/tree/main/TGARNet.

4. Results and Discussion

This section reports the performance of the proposed T-GARNet model under two complementary subject-independent validation schemes: SGKF-CV and LOSO-CV. These protocols assess model robustness to inter-subject variability and acquisition heterogeneity, which are critical for the development of clinically reliable EEG-based diagnostic systems. In addition to classification performance, we evaluate the contribution of the proposed multi-scale Gaussian connectivity module and the –Rényi mutual-information regularization in enabling interpretable and non-redundant spatial representations.

Performance was quantified using standard binary classification metrics computed at the segment level. Let , , , and denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. We report

All metrics were averaged across folds, and standard deviations were computed to quantify performance variability across subjects.

4.1. Performance Under the LOSO-CV Protocol

Table 3 presents the performance of all models under the LOSO evaluation protocol. Consistent with prior ADHD EEG studies employing subject-wise validation, all end-to-end deep learning architectures achieve high precision, with EEGNet and CNN–LSTM leading, closely followed by T-GARNet and ShallowConvNet. This convergence toward ceiling-level performance reflects the well-known behavior of LOSO in small-to-medium EEG datasets, where overlapping temporal windows from the same subject preserve individual-specific spectral–temporal fingerprints across folds.

Table 3.

LOSO-CV accuracy performance across models.

Under these favorable conditions, T-GARNet demonstrates competitive performance, achieving precision comparable to top baselines. This confirms that the addition of multi-scale Gaussian connectivity modeling and -Rényi regularization does not impede discriminative capacity when subject-specific signal structure is implicitly shared across training and test partitions. Moreover, the variance pattern across architectures follows expected trends: models relying heavily on global attention exhibit greater variability, reflecting sensitivity to subject-specific noise, whereas T-GARNet preserves stability by enforcing spatial structure and information diversity constraints.

Overall, while LOSO does not fully expose differences in generalization behavior due to its optimistic bias, T-GARNet remains on par with leading deep learning baselines. This motivates the complementary use of the SGKF–CV protocol, which enforces separation across subject groups and provides a more realistic estimate of out-of-distribution clinical performance.

4.2. Performance Under the SGKF-CV Protocol

Before assessing model generalization under the full evaluation protocol, we conducted a set of ablation experiments to quantify the contribution of each architectural component in T-GARNet. Three reduced variants were trained under identical SGKF-CV conditions: (i) a model without the Transformer block, isolating the role of temporal attention; (ii) a model without the Gaussian connectivity operator, which implicitly suppresses the -Rényi regularization since it functions as a connectivity prior; (iii) a model that retains the connectivity module but removes the -Rényi mutual-information regularizer, testing its effect independent of structural connectivity learning. Table 4 summarizes the averaged performance across folds.

Table 4.

Ablation study under SGKF-CV showing mean accuracy and variability across folds. Removing temporal modeling or connectivity mechanisms consistently degrades performance.

These results reveal that the degradation is modest when temporal attention is removed, but substantial when functional connectivity modeling or its regularization is disabled (7.7 and 6.1 percentage points, respectively). This indicates that the joint representation of long-range temporal dependencies and multi-scale connectivity interactions is not only beneficial but necessary for stable generalization. Motivated by these observations, we next evaluate the full architecture under a more stringent protocol designed to approximate deployment-level conditions.

Having confirmed through ablation that all architectural components contribute meaningfully to performance, we next assess whether these gains translate into competitive advantages under realistic evaluation conditions. To obtain a realistic estimate of clinical generalization, we performed a stratified group k-fold cross-validation where entire subject groups were held out in each fold. This protocol enforces subject-level independence while avoiding optimistic bias that may arise in LOSO settings due to segment overlap and subject-specific patterns. Unlike LOSO, SGKF-CV evaluates whether the model can generalize to larger unseen cohorts, closely reflecting deployment scenarios where new patients exhibit distinct noise characteristics and individual neurophysiological variability.

Table 5 reports the average performance across folds. Consistent with ablation trends, T-GARNet exhibits the highest accuracy and recall among all evaluated models, marginally outperforming ShallowConvNet and CNN–LSTM, which rank as the strongest conventional baselines. EEGNet shows moderate results, whereas the Multi-Stream Transformer and ANOVA–PCA SVM exhibit comparatively weak performance profiles. The IM–CBGT model also falls below these architectures, with accuracy, recall, and precision concentrated around 65%, indicating limited generalization when trained over engineered feature streams rather than fully end-to-end representations. This ordering reinforces the importance of jointly modeling temporal dependencies and connectivity structure, as architectures lacking one or both elements fail to achieve competitive cross-subject generalization.

Table 5.

Performance comparison under the SGKF-CV protocol. T-GARNet shows robust performance across metrics.

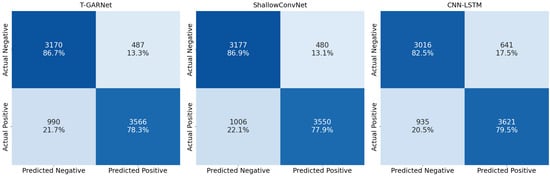

Although ShallowConvNet and CNN–LSTM achieve comparable class-wise performance, T-GARNet offers the most balanced discrimination profile, maintaining high specificity (86.7%) while achieving competitive sensitivity to ADHD cases (78.3%). ShallowConvNet yields a similar trade-off but with slightly lower recall, whereas CNN–LSTM shows stronger sensitivity at the expense of reduced specificity. Importantly, this improved balance is achieved with substantially fewer trainable parameters (as shown in Table 2): T-GARNet is more compact than both ShallowConvNet (33,762 parameters) and CNN–LSTM (8752 parameters), while integrating richer modeling components such as temporal attention and connectivity regularization. In contrast, IM–CBGT exhibits much weaker discriminative capability despite being the largest model in the benchmark, further underscoring that architectural complexity alone does not guarantee generalization under cohort shifts. This supports the view that the moderate gains of T-GARNet are justified not only by performance but also by parameter efficiency and interpretability, which are desirable properties for clinical deployment. These patterns are visually reflected in the confusion matrices in Figure 6, where T-GARNet exhibits the most equitable distribution of correct classifications between ADHD and control groups, while alternative models display either more conservative or more permissive decision tendencies.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrices for the strongest baseline models under the SGKF-CV protocol. T-GARNet achieves the highest proportion of correctly detected ADHD cases (78.3%), reflecting superior sensitivity without notably increasing false positives. ShallowConvNet exhibits a similar but slightly lower detection profile (77.9%), while CNN–LSTM shows comparatively reduced sensitivity to ADHD segments (79.5%) but higher false positive rates.

4.3. Statistical Significance Analysis

To determine whether performance differences across models were statistically meaningful, we conducted a Friedman ranking test followed by Wilcoxon signed-rank post hoc comparisons with Holm correction [56]. All statistics were computed using 50 accuracy values per model (5 folds × 10 repetitions).

The Friedman test indicated a significant overall effect (, ), confirming that model choice materially influences predictive performance. The updated average ranks in Table 6 place T-GARNet as the best-ranked model (2.54), followed by ShallowConvNet (2.70) and CNN–LSTM (2.76), forming a cluster of strong competitors. EEGNet occupies the middle tier, whereas the Multi-Stream Transformer, ANOVA–PCA SVM, and IM–CBGT obtain progressively poorer rankings. Notably, IM–CBGT achieves the worst average rank despite its architectural complexity, aligning with its weak generalization under SGKF-CV.

Table 6.

Statistical comparison of models under SGKF-CV. Lower rank is better. Significance refers to Wilcoxon post hoc test with Holm correction against T-GARNet ().

Holm-corrected Wilcoxon comparisons reveal statistically significant differences between T-GARNet and the weakest baselines (ANOVA–PCA SVM, IM–CBGT, and Multi-Stream Transformer). In contrast, no significant differences were observed between T-GARNet and ShallowConvNet, CNN–LSTM, or EEGNet at the threshold, reflecting competitive behavior among high-capacity neural architectures when evaluated under strict subject-independent conditions. Several additional pairwise differences emerged among lower-ranked models, particularly highlighting IM–CBGT’s inferiority relative to ShallowConvNet, CNN–LSTM, and EEGNet.

Counting fold-level wins supports this trend: T-GARNet achieved the highest number of partition wins (21/50), while ShallowConvNet and CNN–LSTM each won 10 partitions and EEGNet won 9. No wins were observed for the remaining models, consistent with their lower rankings and significance outcomes.

Overall, these results confirm that T-GARNet either matches or exceeds state-of-the-art competitors in subject-level generalization, while weaker models such as IM–CBGT underperform despite architectural sophistication. This reinforces the value of explicitly modeling temporal attention and connectivity structure, and supports the claim that T-GARNet provides improved performance without sacrificing statistical robustness.

4.4. Transformer-Based Channel Importance Analysis

To investigate the spatial contributions learned by the Transformer encoder, we analyzed the attention projection weights extracted from the trained T-GARNet model. For each head h, we computed an inter-channel interaction matrix [57]:

which measures how strongly each EEG channel queries information from others. Averaging across all heads yields

The column-wise -norm of defines the attention importance vector , reflecting how often each channel is consulted:

To incorporate the magnitude of the value projections, the overall content importance is computed as

yielding a normalized distribution of channel relevance across the EEG montage. This metric effectively combines how much a channel is queried (attentional demand) and how much information it contributes (content strength).

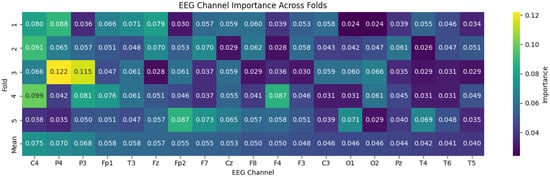

Figure 7 summarizes the channel-level importance scores across folds. Consistently across runs, the highest weights concentrate on midline and parietal electrodes (C4, P4, and P3), followed by prefrontal regions (Fp1/Fp2), reflecting the engagement of fronto-parietal control circuits often implicated in ADHD neurodynamics. Channels located in posterior and temporal areas exhibit comparatively lower weights, suggesting limited direct contribution to the temporal encoding learned by the Transformer.

Figure 7.

Channel-wise importance heatmap derived from Transformer encoder weights across cross-validation folds. The consistent spatial patterns across folds indicate stable feature attribution, supporting the reliability of the learned attention mechanism and its suitability for interpretability analysis in EEG-based ADHD detection.

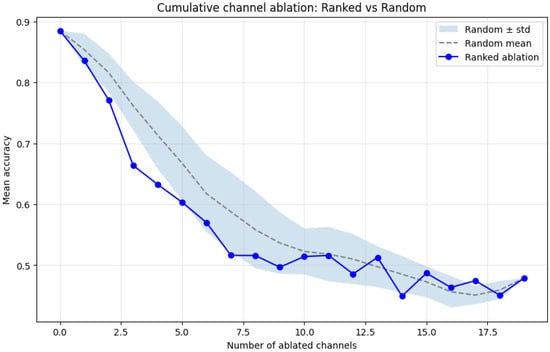

To quantitatively assess the functional relevance of these learned importance scores, we performed a channel ablation experiment. Channels were progressively deactivated (set to zero) following two schemes: (1) ranked order according to , and (2) random order, averaged over 50 repetitions. Figure 8 shows the resulting mean accuracy drop as channels were removed. The ranked ablation curve declines sharply compared to the random baseline, indicating that early removal of the most important channels significantly degrades classification accuracy.

Figure 8.

Cumulative channel ablation analysis comparing ranked and random removal orders. Shaded area shows random mean ± standard deviation across 50 iterations.

A two-sample t-test between the ranked and random ablations for the first five removals yielded a statistically significant difference (), confirming that the Transformer-identified channels encode discriminative information critical for the ADHD control distinction.

4.5. Learned Connectivity Patterns

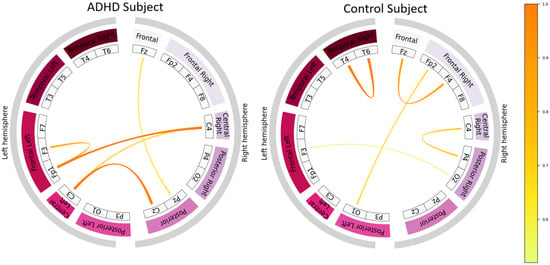

To gain insight into the neurophysiological representations captured by the proposed model, we analyzed the Gaussian–kernel connectivity matrix produced by the intermediate layer of T-GARNet. This matrix encodes pairwise channel interactions learned directly from raw EEG, allowing us to examine emergent connectivity patterns without imposing predefined frequency bands or handcrafted connectivity metrics.

For interpretability analysis, we selected the trained model from the fifth SGKF fold and extracted connectivity representations for subjects in the held-out test group. For each individual, connectivity matrices were computed for all EEG segments and then averaged to obtain a stable subject-level connectivity map. To focus on the most salient modeled interactions, we visualized only the top 10% strongest learned connections in each subject.

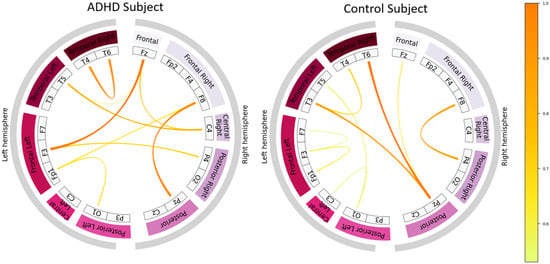

Figure 9 displays these connectivity diagrams for two correctly classified cases, one ADHD and one control subject. Each chord represents a learned functional interaction between EEG channels, with line thickness and color indicating kernel magnitude and thus the strength of modeled coupling.

Figure 9.

Top 10% strongest learned EEG connectivity patterns extracted from the Gaussian kernel layer of T-GARNet for a correctly classified ADHD subject (left) and a correctly classified control subject (right). Connectivity estimates correspond to the segment-averaged representation from the fifth SGKF-CV fold.

Qualitative differences are apparent between ADHD and control subjects. The control subject exhibits a more localized and spatially coherent connectivity architecture, dominated by short-range frontal and temporal couplings. By contrast, the ADHD subject shows broader and more diffuse connectivity, including long-range fronto-parietal and interhemispheric interactions. Importantly, these patterns do not exhibit strong hemispheric symmetry in either class; instead, the most distinctive feature is the spatial extent and distribution of strong functional links. Such differences align with evidence of atypical large-scale organization and reduced network efficiency in ADHD, particularly in executive and attentional circuits.

To further contextualize model behavior, Figure 10 shows two misclassified subjects—one ADHD subject predicted as control and one control subject predicted as ADHD. Their connectivity patterns display mixed or ambiguous characteristics. Specifically, misclassified ADHD cases tend to exhibit a connectivity organization that is less diffuse than typical ADHD patterns, whereas misclassified controls often display unusually extended long-range connections. These hybrid patterns deviate from the more canonical organization observed in correctly classified subjects, providing a plausible neurophysiological explanation for model uncertainty.

Figure 10.

Top 10% strongest learned EEG connectivity patterns for misclassified subjects: an ADHD subject predicted as control (left) and a control subject predicted as ADHD (right). Ambiguous combinations of localized and long-range couplings distinguish these patterns from those of correctly classified subjects.

Overall, the emergence of clinically meaningful connectivity signatures—despite the absence of explicit functional connectivity priors—suggests that the multi-scale Gaussian kernel mechanism embedded in T-GARNet captures structured coupling patterns relevant to ADHD neurophysiology. In conjunction with the model’s competitive classification performance, these results highlight the potential of T-GARNet as both a diagnostic tool and a framework capable of revealing mechanistic alterations in large-scale EEG connectivity.

4.6. Class-Wise Spatial Relevance via Grad-CAM++

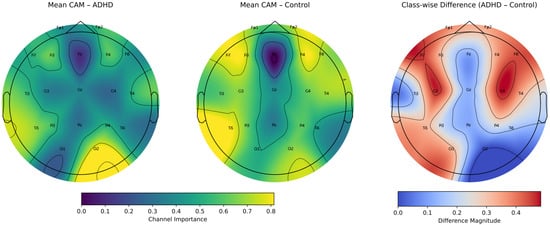

To further inspect the spatial representations learned by T-GARNet, we computed class-specific activation maps (CAMs) from the last convolutional layer using the Grad-CAM++ implementation provided by keras-vis. For interpretability and to avoid information leakage, CAMs were calculated exclusively over the held-out test subjects from the SGKF-CV fold where Fold 5 served as the test partition.

For each test trial, a CAM was extracted, and the maps were then averaged separately across ADHD and Control samples:

To derive a channel-level relevance score, each CAM was collapsed across time:

Because the absolute magnitudes of these vectors may differ across classes, both relevance vectors were jointly normalized using their shared minimum and maximum:

with

Finally, the class-wise discriminative magnitude was computed as

highlighting channels whose relevance differs most between classes.

Figure 11 depicts the resulting topographies. The ADHD map (left) shows a frontal midline depression centered on Fz and pronounced posterior relevance with a right-occipital peak around O2, accompanied by contributions in P4/T6 and a secondary lobe near T5. The Control map (middle) exhibits an even deeper valley along the midline (Fz through Cz–Pz) and comparatively elevated lateral activity, yielding a more symmetric peripheral profile. The class-wise difference (right) highlights where the model’s spatial evidence diverges most: the strongest separations occur over fronto-lateral sites (F3/F4) and lateral central electrodes (C3/C4), whereas differences are minimal along the midline axis (Fz–Cz–Pz) and at occipital sites (O1/O2), where both classes show similar levels after joint normalization.

Figure 11.

Class-specific Grad-CAM++ relevance averaged over time and subjects from the test split of Fold 5. (Left): ADHD class relevance. (Middle): Control class relevance. (Right): absolute difference map after joint min–max normalization. ADHD exhibits stronger fronto-central and right frontal–temporal importance, whereas Control shows greater relevance in lateral parietal and posterior regions.

Overall, these CAM-derived patterns show that discrimination emerges primarily from lateral frontal (F3/F4) and central sensorimotor regions (C3/C4), whereas midline activity (Fz–Cz–Pz) remains largely shared between ADHD and control subjects, and occipital contributions are comparably low in both groups. This spatial distribution is consistent with neurophysiological evidence reporting that ADHD-related alterations during sustained attention tasks arise mainly in lateral prefrontal and sensorimotor circuits, rather than in midline executive regions whose engagement is driven by the task demands itself. The observed CAM differences therefore align well with established findings and reinforce a coherent interpretation in which lateral fronto-central dynamics encode most of the class-specific information, while midline and posterior activity reflect common processing across groups.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced T-GARNet, a novel architecture that integrates Transformer-based temporal modeling with a multi-scale Gaussian kernel connectivity module regularized through matrix-based -Rényi mutual information. The model was designed to address three persistent challenges in EEG-based ADHD detection: the dependence on extensive preprocessing pipelines, limited interpretability of deep neural models, and poor generalization under subject-independent evaluation. Across two rigorous validation schemes, LOSO-CV and SGKF-CV, T-GARNet achieved competitive or superior performance relative to widely used convolutional, recurrent, and Transformer-based baselines. Notably, under the more clinically realistic SGKF-CV setting, the proposed framework demonstrated the highest average accuracy and recall while maintaining balanced precision, underscoring its robustness to inter-subject variability and acquisition heterogeneity.

Beyond classification accuracy, T-GARNet provided enhanced interpretability through multiple complementary mechanisms. The Transformer encoder produced channel-attention patterns that consistently emphasized fronto-central and parietal regions implicated in ADHD neurophysiology. The multi-scale Gaussian connectivity module revealed group-specific functional interactions without relying on handcrafted features or predefined frequency bands. Furthermore, the -Rényi regularization successfully encourage diversity across connectivity scales, reducing redundancy and enabling clearer spatial structure. Grad-CAM++ analyses further confirmed class-discriminative relevance in lateral prefrontal and sensorimotor regions known to support attentional control. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that T-GARNet offers a principled and interpretable framework for EEG-based ADHD assessment. By jointly modeling temporal dependencies and connectivity structure while enforcing information-theoretic diversity, the model captures meaningful neurophysiological patterns directly from minimally processed EEG.

Despite the promising results, this study presents several limitations. First, the experiments were conducted on a single pediatric EEG dataset with a relatively limited number of subjects, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to broader clinical populations. Second, although the proposed architecture operates on minimally processed EEG, real-world recordings exhibit greater variability in noise conditions, electrode placement, and comorbidities, all of which warrant further examination. Finally, external validation across independent datasets and diverse clinical environments is needed to fully assess the robustness and translational potential of T-GARNet.

Future work will explore extensions to multi-class ADHD subtyping, cross-dataset generalization, and integration with multimodal neuroimaging to further advance objective and explainable neurodevelopmental diagnostics [58,59]. Furthermore, Graph Neural Network approaches will be explored for modeling the EEG as a dynamic functional connectivity graph, enabling the extraction of topology-aware biomarkers that capture non-linear interactions and network-level alterations associated with ADHD [60]. Finally, subgroup-level analysis represents a promising avenue for future research [61].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.V.S.-D., A.M.Á.-M. and G.C.-D.; data curation, D.V.S.-D.; methodology, D.V.S.-D., A.M.Á.-M. and G.C.-D.; project administration, A.M.Á.-M. and G.C.-D.; supervision, A.M.Á.-M. and G.C.-D.; resources, D.V.S.-D. and A.M.Á.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors gratefully acknowledge support from the program: “Alianza científica con enfoque comunitario para mitigar brechas de atención y manejo de trastornos mentales relacionados con impulsividad en Colombia (ACEMATE)-91908”. This research was supported by the project: “Sistema multimodal apoyado en juegos serios orientado a la evaluación e intervención neurocognitiva personalizada en trastornos de impulsividad asociados a TDAH como soporte a la intervención presencial y remota en entornos clínicos, educativos y comunitarios-790-2023,” funded by the Colombian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Minciencias). Also, A.M. Alvarez gives thanks to the project: “NatureTunes: Inteligencia artificial para el monitoreo de paisajes sonoros y visuales como fomento al aviturismo en el departamento de Caldas”, Hermes-63421, funded by Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Data Availability Statement

The databases and codes used in this study are public and can be found at the following link: https://github.com/dannasalazar11/Msc_thesis/tree/main/TGARNet (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Asherson, P. ADHD across the lifespan. Medicine 2024, 52, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, G.; Demelash, S.; Gizachew, Y.; Tsegay, L.; Alati, R. The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Poppi, C.; Arcolin, E.; Cutino, A.; Ferri, P.; D’Amico, R.; Filippini, T. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: A systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plas, N.E.; Noordermeer, S.D.; Oosterlaan, J.; Luman, M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Predictors of Adult Psychiatric Outcomes of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurjui, I.A.; Hurjui, R.M.; Hurjui, L.L.; Serban, I.L.; Dobrin, I.; Apostu, M.; Dobrin, R.P. Biomarkers and Neuropsychological Tools in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: From Subjectivity to Precision Diagnosis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1211. [Google Scholar]

- Güven, A.; Altınkaynak, M.; Dolu, N.; İzzetoğlu, M.; Pektaş, F.; Özmen, S.; Demirci, E.; Batbat, T. Combining functional near-infrared spectroscopy and EEG measurements for the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 8367–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.Q.; Vera, V.D.G.; Quintero, M.J.R. Diagnosis of ADHD in children with EEG and machine learning: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Health 2025, 36, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. Artificial intelligence in ADHD assessment: A comprehensive review of research progress from early screening to precise differential diagnosis. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1624485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Y.; Li, X. A deep learning framework for identifying children with ADHD using an EEG-based brain network. Neurocomputing 2019, 356, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, A.; He, Y.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: A review. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, A.B.; Flaherty, B.P. A framework for characterizing heterogeneity in neurodevelopmental data using latent profile analysis in a sample of children with ADHD. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2022, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadithy, S.S.; Abdalkafor, A.S.; Al-Khateeb, B. Emotion recognition in EEG Signals: Deep and machine learning approaches, challenges, and future directions. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Y. DMMR: Cross-subject domain generalization for EEG-based emotion recognition via denoising mixed mutual reconstruction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 628–636. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, H.W.; Ooi, C.P.; Oh, S.L.; Barua, P.D.; Tan, Y.R.; Acharya, U.R.; Fung, D.S.S. ADHD/CD-NET: Automated EEG-based characterization of ADHD and CD using explainable deep neural network technique. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2024, 18, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. An end-to-end deep learning model for EEG-based major depressive disorder classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41337–41347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.K.; Acharya, U.R. An explainable and interpretable model for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children using EEG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 155, 106676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtyari, M.; Mirzaei, S. ADHD detection using dynamic connectivity patterns of EEG data and ConvLSTM with attention framework. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 76, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarion, G.; Sparacino, L.; Antonacci, Y.; Faes, L.; Mesin, L. Connectivity analysis in EEG data: A tutorial review of the state of the art and emerging trends. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, A.; Imtiaz, M.H. Automatic identification of children with ADHD from EEG brain waves. Signals 2023, 4, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookshire, G.; Kasper, J.; Blauch, N.M.; Wu, Y.C.; Glatt, R.; Merrill, D.A.; Gerrol, S.; Yoder, K.J.; Quirk, C.; Lucero, C. Data leakage in deep learning studies of translational EEG. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1373515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Singh, B.K. Classification of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using Wigner-Ville time-frequency and deep expEEGNetwork feature-based computational models. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 2023, 5, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; Covino, A.; Cristaldi, L.; Frosolone, M. A systematic review on feature extraction in electroencephalography-based diagnostics and therapy in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sensors 2022, 22, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, T.; Sujatha, S. Common Spatial Pattern based Feature Extractor with Hybrid LinkNet-SqueezeNet for ADHD Detection from EEG Signal. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaghiBeyglou, B.; Hasanzadeh, N. ADHD diagnosis in children using common spatial pattern and nonlinear analysis of filter banked EEG. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Tabriz, Iran, 4–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; Ortiz, E.; Escobar, J. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder classification with EEG and machine learning. In Neuroimaging Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bathula, D.R.; Benet Nirmala Bathula, A. Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging. In Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddari, M.; Lighvan, M.Z.; Danishvar, S. Diagnose ADHD disorder in children using convolutional neural network based on continuous mental task EEG. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tong, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R. SCANet: An Innovative Multiscale Selective Channel Attention Network for EEG-Based ADHD Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 20920–20932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: A compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Chu, Y.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X. AMEEGNet: Attention-based multiscale EEGNet for effective motor imagery EEG decoding. Front. Neurorobot. 2025, 19, 1540033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Ushiba, J. Deep residual convolutional neural networks for brain–computer interface to visualize neural processing of hand movements in the human brain. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 882290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Jing, X.; Yokoi, H.; Huang, W.; Zhu, M.; Chen, S.; Li, G. Towards high-accuracy classifying attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders using CNN-LSTM model. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 046015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Jia, S.; Lun, X.; Hao, Z.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, R.; Lv, J. GCNs-net: A graph convolutional neural network approach for decoding time-resolved eeg motor imagery signals. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 7312–7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushiyant; Mathur, V.; Kumar, S.; Shokeen, V. REEGNet: A resource efficient EEGNet for EEG trail classification in healthcare. Intell. Decis. Technol. 2024, 18, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha Ravindran, A.; Contreras-Vidal, J. An empirical comparison of deep learning explainability approaches for EEG using simulated ground truth. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Ling, S.S.H.; Wong, J.K.W. Exploring the frontier: Transformer-based models in EEG signal analysis for brain-computer interfaces. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 108705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvigne, V.; Wannous, H.; Vandeborre, J.P.; Ris, L.; Dutoit, T. Spatio-temporal analysis of transformer based architecture for attention estimation from eeg. In Proceedings of the 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–25 August 2022; pp. 1076–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Vafaei, E.; Hosseini, M. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A review of architectures and applications in motor imagery, seizure, and emotion classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudler-Flam, J. Rényi mutual information in quantum field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 021603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Murillo, D.G.; Álvarez-Meza, A.M.; Castellanos-Dominguez, C.G. Kcs-fcnet: Kernel cross-spectral functional connectivity network for eeg-based motor imagery classification. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Giraldo, L.G.S.; Jenssen, R.; Principe, J.C. Multivariate Extension of Matrix-Based Rényi’s α-Order Entropy Functional. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Beltagi, M.; Mani, B.S.; Hantash, E.M.; Al Zahrani, A.A.; Toema, O. Challenges in diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pediatric practice: A regional and global perspective. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2025, 14, 111684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guella, J.C. On Gaussian kernels on Hilbert spaces and kernels on hyperbolic spaces. J. Approx. Theory 2022, 279, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Llamas, L.R.; Guardado-Medina, R.O.; Garcia, A.; Mendez-Vazquez, A. Kernel Learning by Spectral Representation and Gaussian Mixtures. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, J.C. Information Theoretic Learning: Renyi’s Entropy and Kernel Perspectives; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, L.G.S.; Rao, M.; Principe, J.C. Measures of entropy from data using infinitely divisible kernels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2014, 61, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kschischang, F.R. The Wiener-Khinchin Theorem; The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.P. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrabadi, A.M. EEG Data for ADHD/Control Children. 2020. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/eeg-data-adhd-control-children (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Kohavi, R. A Study of Cross-Validation and Bootstrap for Accuracy Estimation and Model Selection. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995; pp. 1137–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert, D. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharif, N.; Al-Adhaileh, M.H.; Al-Yaari, M. Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A deep learning approach. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 10580–10608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, D.W.; Zumbo, B.D. Relative power of the Wilcoxon test, the Friedman test, and repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks. J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 62, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhage, N.; Nanda, N.; Olsson, C.; Henighan, T.; Joseph, N.; Mann, B.; Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Conerly, N.; et al. A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits; Technical report; Anthropic: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; Transformer Circuits Thread. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Martin, E.; Li, X. Machine learning in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: New approaches toward understanding the neural mechanisms. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.N.; Khan, N. Enhanced cross-dataset electroencephalogram-based emotion recognition using unsupervised domain adaptation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 184, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Peng, X.; Han, L. ADHD detection from EEG signals using GCN based on multi-domain features. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1561994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, H. Brain functional differences among ADHD subtypes in children revealed by phase-amplitude coupling analysis of resting-state EEG. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2025, 215, 113222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).