Dual-Branch Network for Video Anomaly Detection Based on Feature Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This work presents DBIFF-Net, a new video anomaly detection framework that tightly couples a CNN-based local encoder with a swin transformer–based global encoder. Unlike prior dual-branch architectures that simply concatenate or sum multi-scale features, DBIFF-Net is designed to jointly capture fine-grained spatial cues and long-range temporal dependencies through interactive fusion, leading to more discriminative multi-scale representations.

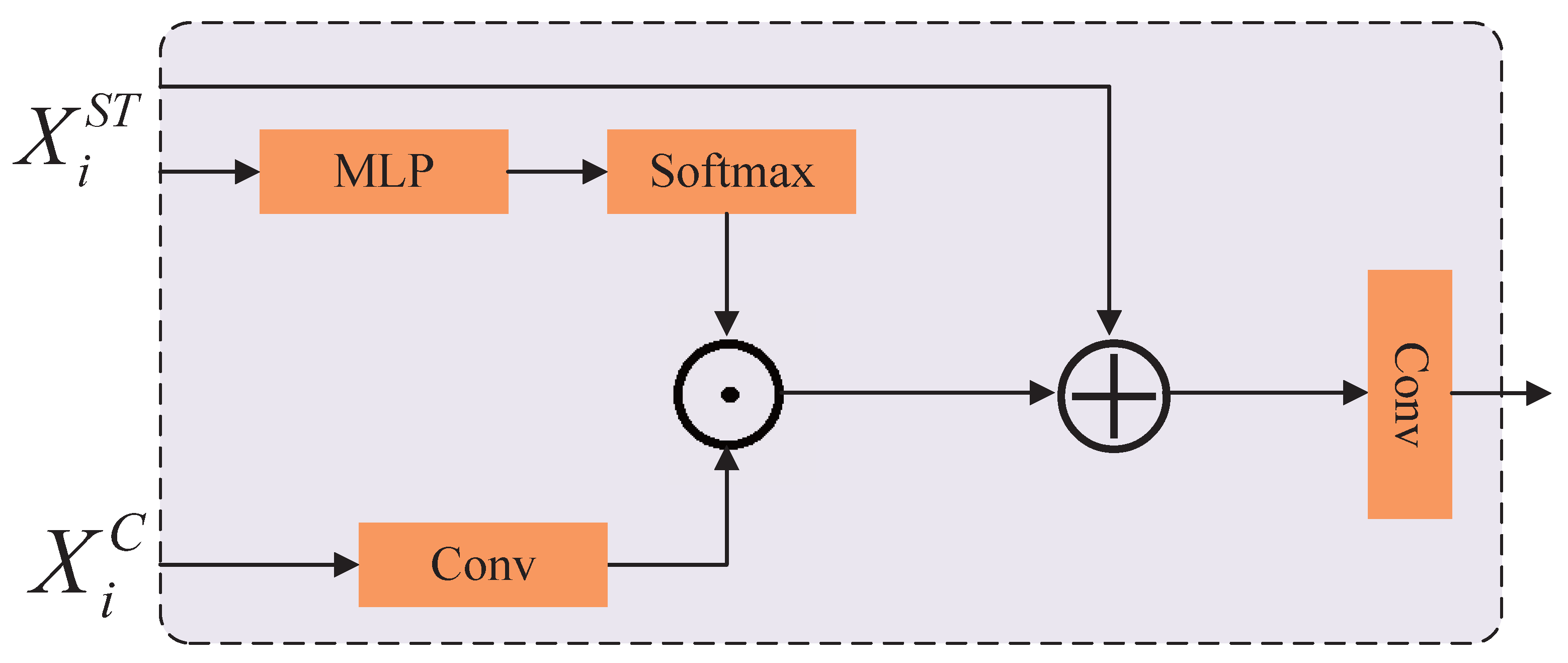

- This work proposes an interactive fusion module to facilitate fusion of multi-scale features between local and global encoders. The module performs dynamic, cross-scale interaction, allowing features from different semantic levels and branches to reinforce each other and significantly enhance representation quality.

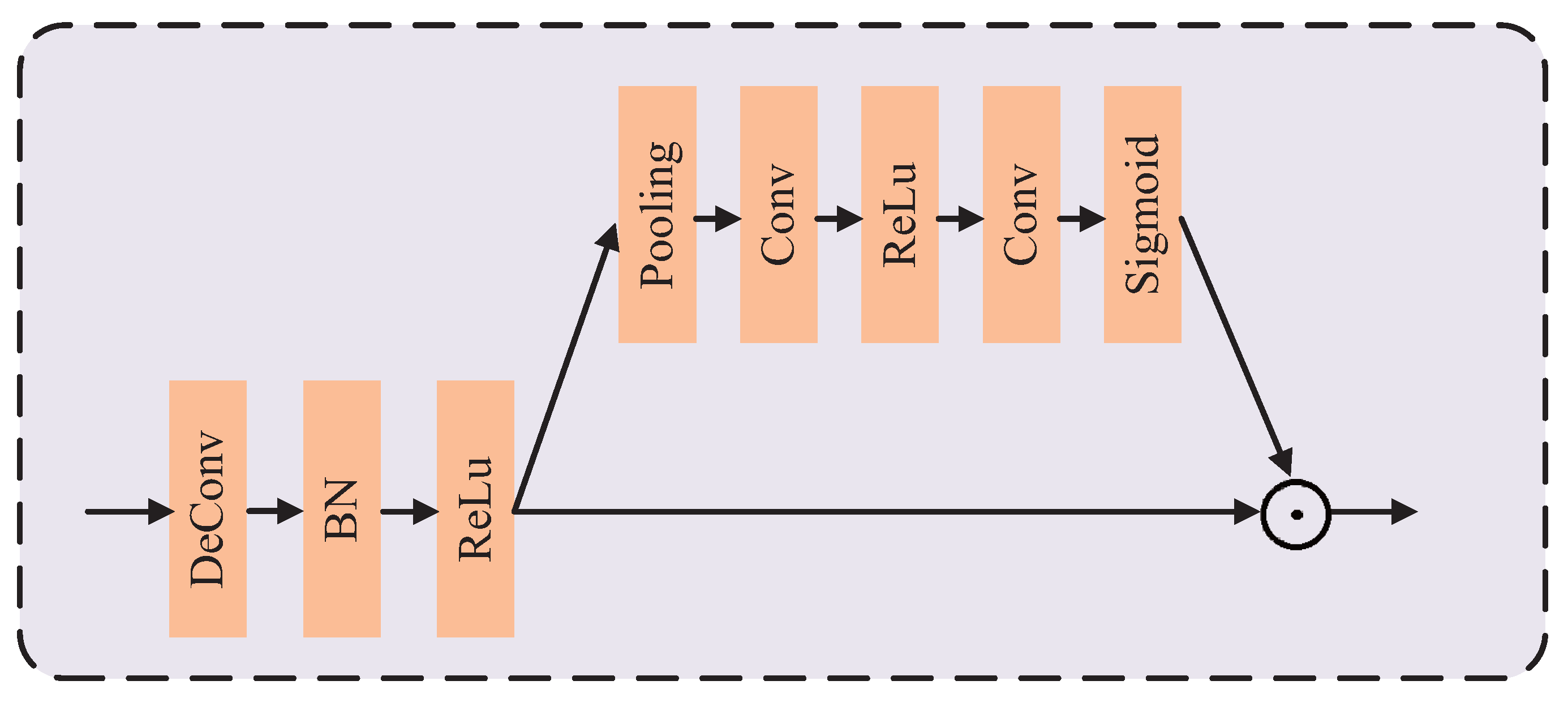

- This work proposes an attention decoder module that employs the channel attention to explicitly models inter-channel dependencies during upsampling, thereby improving the recovery of complex object features.

- Comprehensive experiments show that DBIFF-Net surpasses most methods across three benchmark datasets, and extensive ablation studies validate the necessity and effectiveness of each module, confirming the soundness of the overall architectural design.

2. Related Work

3. Methods

3.1. Dual-Branch Encoder

3.1.1. CNN Local Branch

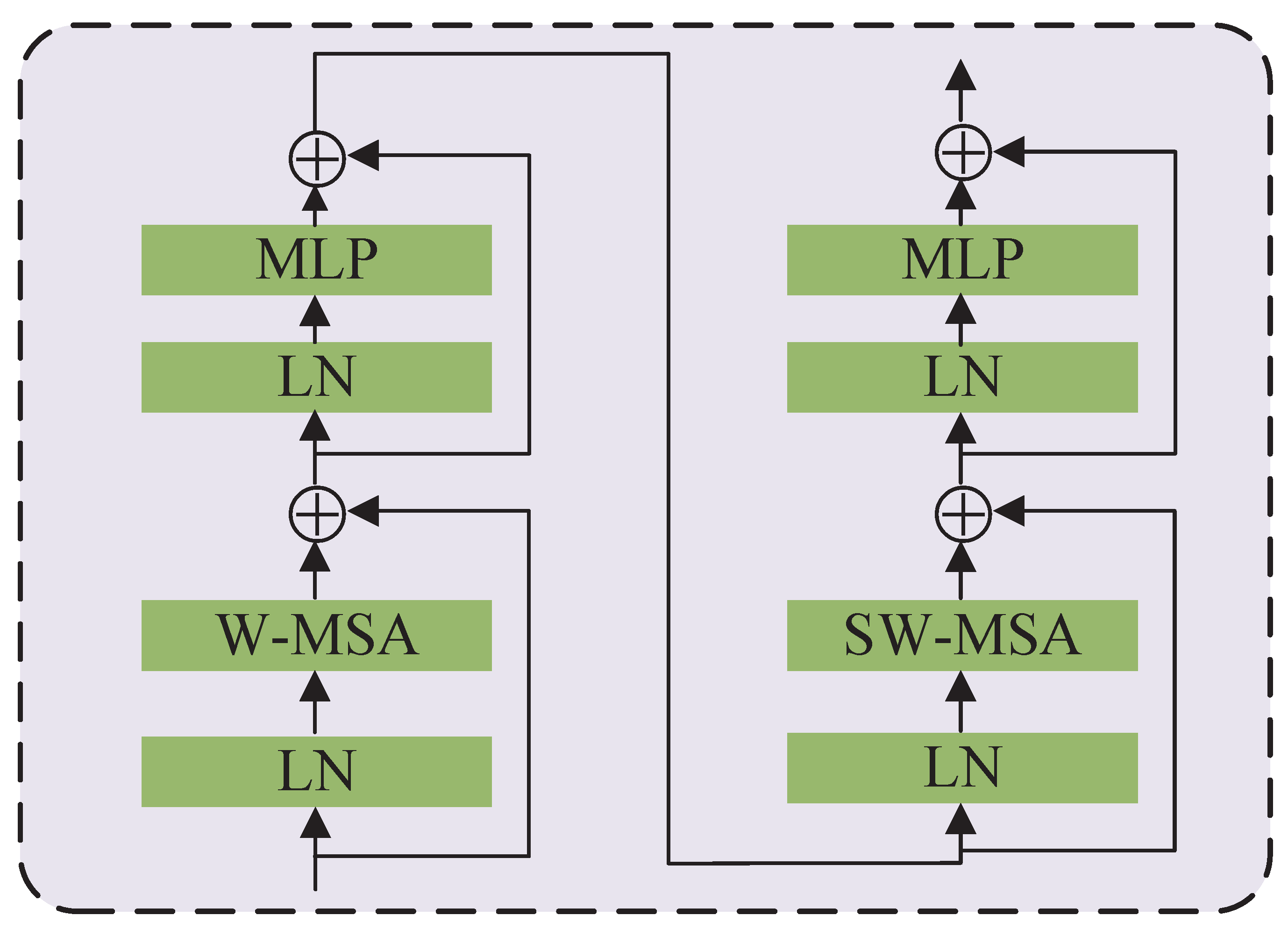

3.1.2. Swin Transformer Global Branch

3.2. Decoder

3.2.1. Interactive Fusion Module

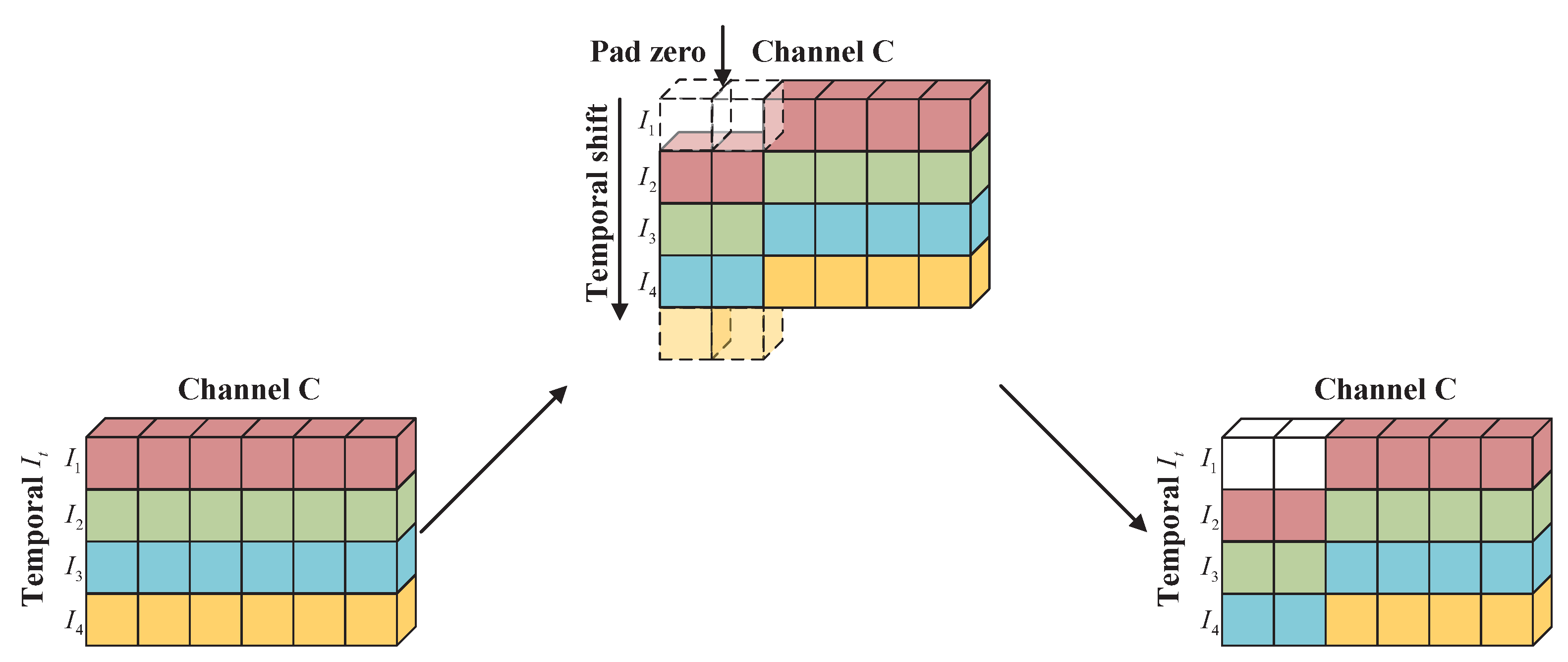

3.2.2. Temporal Shift Module

3.2.3. Attention Decoder Module

3.2.4. Loss Function

3.2.5. Anomaly Detection

4. Comparative Experiments

4.1. Datasets

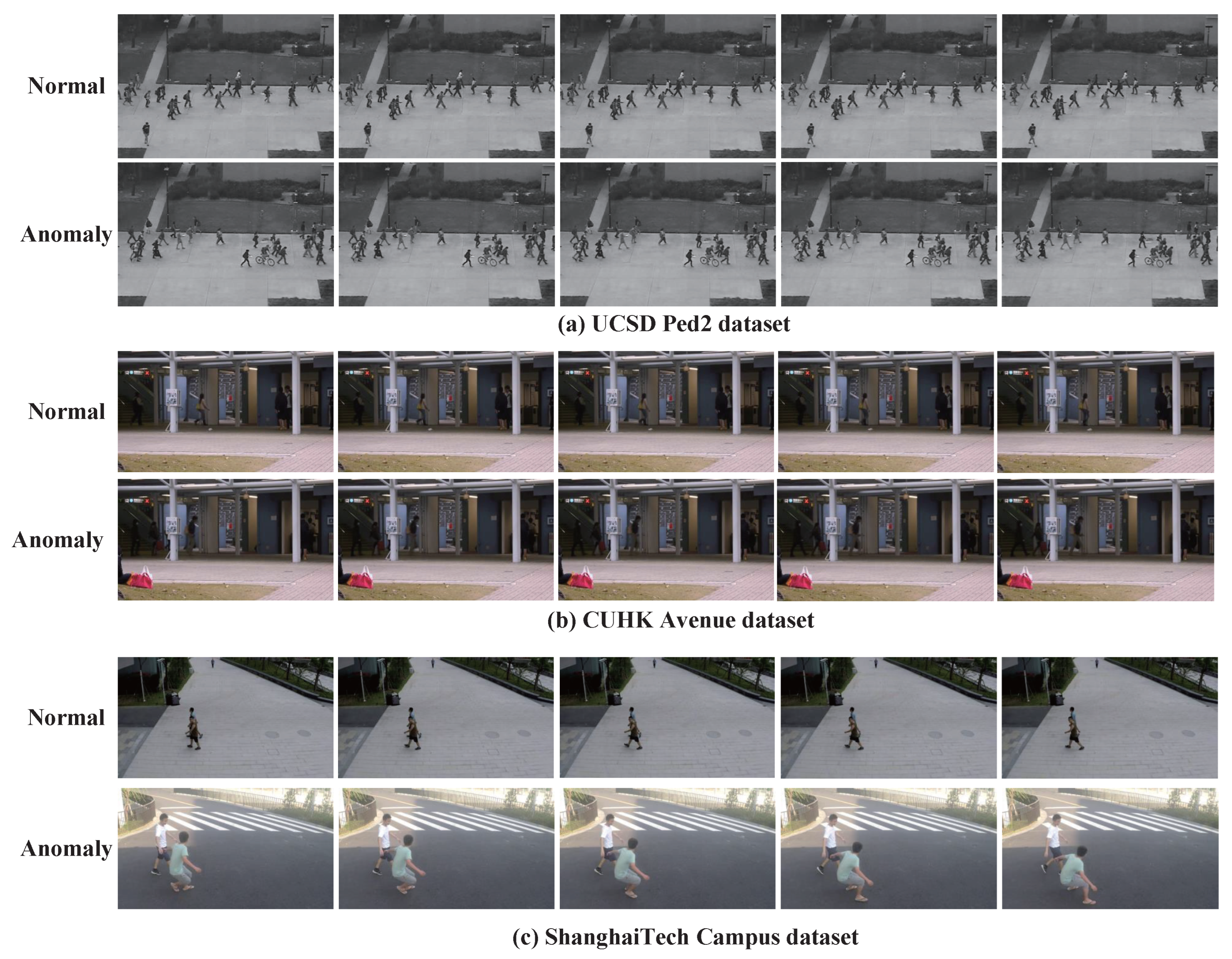

- UCSD ped2 Dataset. The UCSD ped2 dataset was recorded on the pedestrian walkways of the University of California San Diego. Sample cases are illustrated in Figure 6a. In this dataset, walking is defined as normal behavior, while activities such as cycling and skateboarding are considered anomalies. It contains 16 training videos and 12 testing videos. In experiments, the training videos are extracted into 2550 frames, while the testing videos are extracted into 2010 frames, all with a resolution of 240 × 360 pixels.

- CUHK Avenue. The CUHK Avenue was recorded on the CUHK campus avenue. It consists of 16 training videos and 21 testing videos, covering 47 abnormal events, such as jumping, throwing objects, and dancing. Figure 6b shows the sample cases of this dataset. In experiments, the training videos are extracted into 15,328 frames, while the testing videos are extracted into 15,324, all with a resolution of 360 × 640 pixels.

- ShanghaiTech Campus dataset. The ShanghaiTech Campus dataset dataset was created by ShanghaiTech University, featuring footage captured in diverse environments including the university campus, Shanghai streets, and commercial districts. It contains 130 distinct anomaly categories, such as climbing, cycling, and jumping, thereby presenting considerable challenges for video anomaly detection tasks. Figure 6c shows the sample cases of this dataset. The dataset comprises 330 training videos and 107 testing videos. In experiments, the training videos are extracted into 274,515 frames, and the testing videos are extracted into 42,883, all with a resolution of 480 × 856 pixels.

4.2. Training Details

4.3. Evaluation Metric

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art

4.5. Ablation Study and Analysis

4.5.1. The Impact of Dual-Branch Networks on Performance

4.5.2. Impact of Fusion Methods on Performance

4.5.3. Effectiveness of Each Component in Decoder

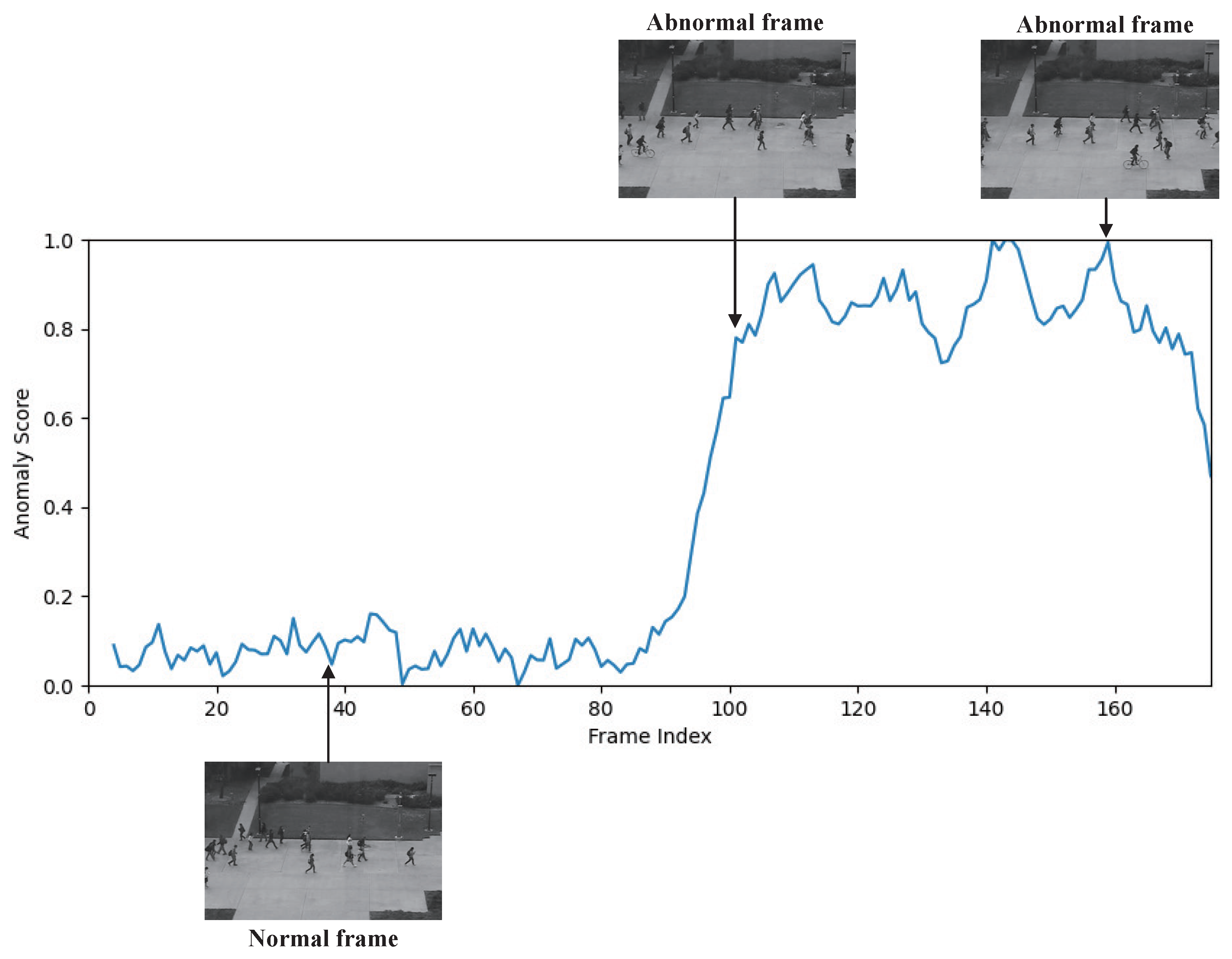

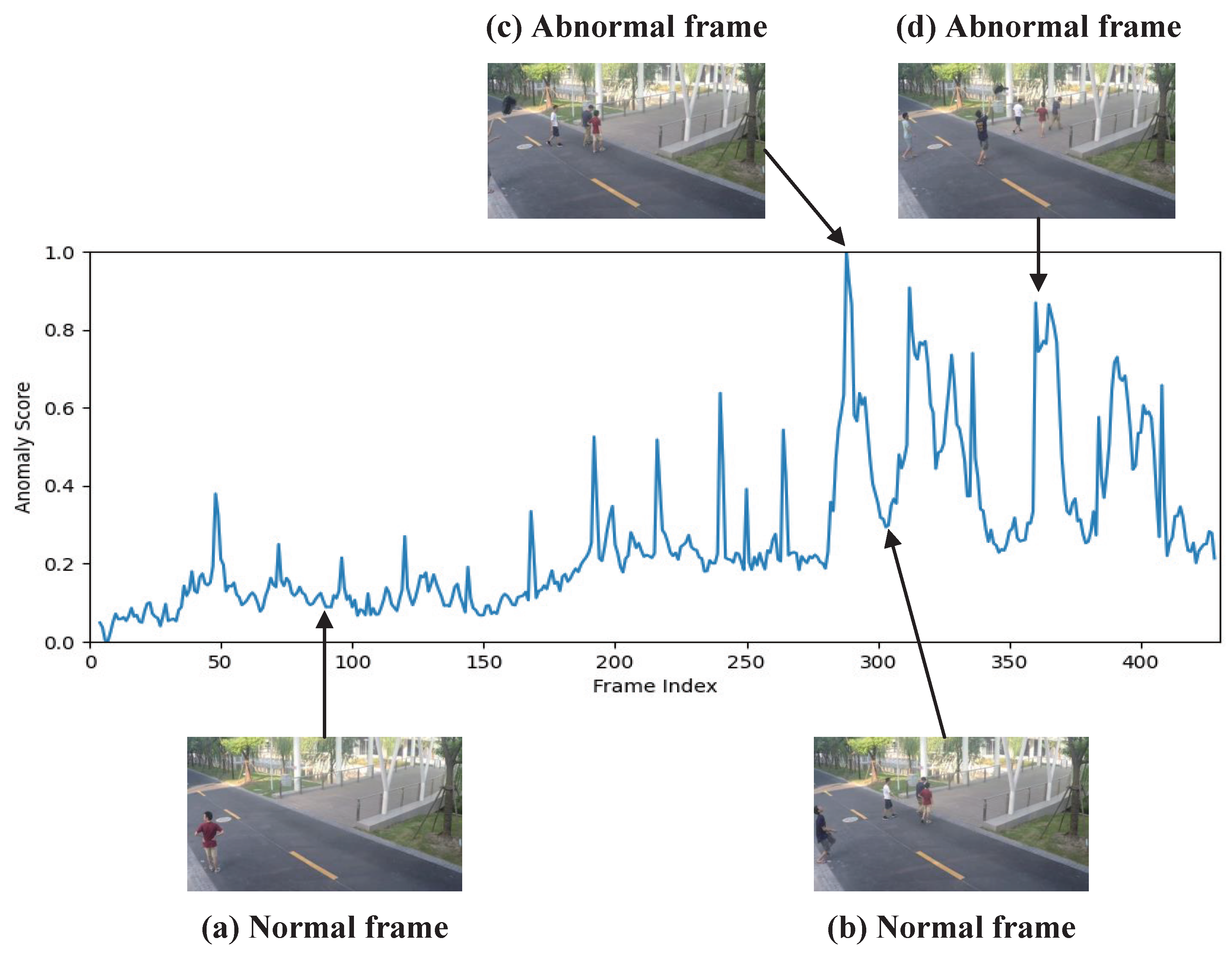

4.5.4. Visualization

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kashef, M.; Visvizi, A.; Troisi, O. Smart city as a smart service system: Human-computer interaction and smart city surveillance systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaila, Y.A.; Sebastian, P.; Singh, N.S.S.; Shuaibu, A.N.; Ali, S.S.A.; Amosa, T.I.; Abro, G.E.M.; Shuaibu, I. Video anomaly detection: A systematic review of issues and prospects. Neurocomputing 2024, 591, 127726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Spoken instruction understanding in air traffic control: Challenge, technique, and application. Aerospace 2021, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Pan, C.; Yan, Y.; Pang, G.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. Deep learning for video anomaly detection: A review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.05383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, F.; Communications Axis. Intelligent Network Video: Understanding Modern Video Surveillance Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwo, O.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Oyelade, O.N.; Almutairi, M.S. Enhanced intelligent smart home control and security system based on deep learning model. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9307961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Boukerche, A.; Sun, P.; Song, L. Generalized video anomaly event detection: Systematic taxonomy and comparison of deep models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, A.O.; Dall’Asen, N.; Beyan, C.; Ricci, E. Exploring diffusion models for unsupervised video anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2540–2544. [Google Scholar]

- Astrid, M.; Zaheer, M.Z.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.I. Learning not to reconstruct anomalies. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.09742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Choi, J.; Neumann, J.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K.; Davis, L.S. Learning temporal regularity in video sequences. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 733–742. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Tan, Y.; Xing, M.; An, S. VPE-WSVAD: Visual prompt exemplars for weakly-supervised video anomaly detection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 299, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, M.; Bergevin, R. A critical study on the recent deep learning based semi-supervised video anomaly detection methods. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 27761–27807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, O.; Shanableh, T. Static video summarization using video coding features with frame-level temporal subsampling and deep learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Hsieh, J.W.; Tsai, L.W.; Chen, S.Y.; Fan, K.C. Carried object detection using ratio histogram and its application to suspicious event analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2009, 19, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Monga, V.; Bala, R.; Fan, Z. Adaptive sparse representations for video anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2013, 24, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidine, B.M.; Fergani, L.; Fergani, B.; Oussalah, M. The joint use of sequence features combination and modified weighted SVM for improving daily activity recognition. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2018, 21, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L.; Peng, X. A novel random forests based class incremental learning method for activity recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 78, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saligrama, V.; Chen, Z. Video anomaly detection based on local statistical aggregates. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2112–2119. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Bai, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, X.; Fu, Y. Making reconstruction-based method great again for video anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Orlando, FL, USA, 28 November–1 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1215–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, P.; Gao, N.; Huan, R.; Zhao, D. Generate anomalies from normal: A partial pseudo-anomaly augmented approach for video anomaly detection. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 3843–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lam, K.M.; Kong, J. Distilling privileged knowledge for anomalous event detection from weakly labeled videos. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 12627–12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, W.; Kong, J. Multi-scale Differential Perception Network for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Auckland, New Zealand, 2–6 December 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.; Ye, J.; Zhao, J.; He, L.; Liu, L.; Huang, X. Video anomaly detection guided by clustering learning. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 153, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Qi, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Ren, P.; Ma, R.; Liao, J. Multi-scale video anomaly detection by multi-grained spatio-temporal representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 17385–17394. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Tan, Y.; An, S.; Xing, M. Anomalies cannot materialize or vanish out of thin air: A hierarchical multiple instance learning with position-scale awareness for video anomaly detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Gan, C.; Han, S. Tsm: Temporal shift module for efficient video understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7083–7093. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Sun, P.; Hu, B.; Song, L.; Boukerche, A.; Leung, V.C. Networking systems for video anomaly detection: A tutorial and survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guo, W. Auto-encoders in deep learning—a review with new perspectives. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Liu, L.; Le, V.; Saha, B.; Mansour, M.R.; Venkatesh, S.; Hengel, A.v.d. Memorizing normality to detect anomaly: Memory-augmented deep autoencoder for unsupervised anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1705–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Nie, Y.; Long, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G. A hybrid video anomaly detection framework via memory-augmented flow reconstruction and flow-guided frame prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 13588–13597. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, B.; Shen, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Hua, X.S. Spatio-temporal autoencoder for video anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 1933–1941. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Cai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Transanomaly: Video anomaly detection using video vision transformer. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 123977–123986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kang, P. Anovit: Unsupervised anomaly detection and localization with vision transformer-based encoder-decoder. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 46717–46724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Gao, S.; Hao, Z. Appearance-motion memory consistency network for video anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 938–946. [Google Scholar]

- Thakare, K.V.; Sharma, N.; Dogra, D.P.; Choi, H.; Kim, I.J. A multi-stream deep neural network with late fuzzy fusion for real-world anomaly detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 201, 117030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Kheddar, H.; Al-Maadeed, N.; Abualsaud, K.; Mohamed, A.; Khattab, T. Video surveillance using deep transfer learning and deep domain adaptation: Towards better generalization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 119, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ju, B.; Yang, D.; Peng, L.; Li, D.; Sun, P.; Li, C.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Song, L. Memory-enhanced spatial-temporal encoding framework for industrial anomaly detection system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Sun, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Yu, Z.; Kang, Y.; Xu, H. Cross-Modal Two-Stream Target Focused Network for Video Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference in Communications, Signal Processing, and Systems, Changbaishan, China, 23–24 July 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Mahadevan, V.; Vasconcelos, N. Anomaly detection and localization in crowded scenes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 36, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Abnormal event detection at 150 fps in matlab. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 2720–2727. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Liu, W.; Gao, S. A revisit of sparse coding based anomaly detection in stacked rnn framework. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Noh, J.; Ham, B. Learning memory-guided normality for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 14372–14381. [Google Scholar]

- Aich, A.; Peng, K.C.; Roy-Chowdhury, A.K. Cross-domain video anomaly detection without target domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2023; pp. 2579–2591. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, L. Memory-enhanced appearance-motion consistency framework for video anomaly detection. Comput. Commun. 2024, 216, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, P.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, M. Dual GroupGAN: An unsupervised four-competitor (2V2) approach for video anomaly detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 153, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Ouyang, Y.; Lu, J.; Yang, Y.; Sanchez, V. Advancing video anomaly detection: A bi-directional hybrid framework for enhanced single-and multi-task approaches. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 6865–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Zhen, P.; Yan, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Chen, H. MemATr: An Efficient and Lightweight Memory-augmented Transformer for Video Anomaly Detection. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2025, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Epoch | 120 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Learning rate | |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| The length of input video frame (t) | 5 |

| The stage N of convolution module and swin transformer module | 3 |

| The size of patch | 4 |

| The depth of swin transformer block | [2, 2, 2] |

| The attention head of swin transformer block | [4, 8, 16] |

| Dropout | 0.5 |

| The Number of channels for temporal shift | 32 |

| Methods | UCSD Ped2 | CUHK Avenue | ShanghaiTech Campus Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE-Conv2D [10] | 90.0 | 70.2 | 60.9 |

| Mem-AE [30] | 94.1 | 71.1 | 71.2 |

| MNAD-Recon [43] | 90.2 | 82.8 | 69.8 |

| zxVAD [44] | 95.8 | 83.1 | 71.6 |

| MAMC-Net [45] | 96.7 | 87.6 | 71.5 |

| Dual GroupGAN [46] | 96.6 | 85.5 | 73.1 |

| BDHF [47] | 96.4 | 86.5 | 73.6 |

| CLAE [23] | 90.8 | 83.1 | 73.3 |

| Dang et al. [20] | 96.0 | 85.9 | 73.3 |

| MemATr [48] | 95.2 | 83.8 | 73.4 |

| DBIFF-Net (Ours) | 97.7 | 84.5 | 73.8 |

| Dataset | Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCSD Ped2 | Dang et al. [20] | 96.0 | 93.6 | 94.8 |

| DBIFF-Net (Ours) | 97.1 | 96.2 | 96.7 | |

| CUHK Avenue | Dang et al. [20] | 62.1 | 71.4 | 64.4 |

| DBIFF-Net (Ours) | 57.4 | 75.4 | 65.2 | |

| ShanghaiTech Campus | Dang et al. [20] | 53.2 | 85.6 | 65.0 |

| DBIFF-Net (Ours) | 58.2 | 74.1 | 65.2 |

| Methods | UCSD Ped2 |

|---|---|

| Single-CNN | 97.2 |

| Single-swin transformer | 84.1 |

| DBIFF-NET (dual-branch) | 97.7 |

| Fusion Methods | UCSD Ped2 |

|---|---|

| SUM | 97.2 |

| QA | 97.7 |

| CON | 96.9 |

| Interactive Fusion | 97.7 |

| Interactive Fusion Module | TSM | Channel Attention | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 96.4 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 96.5 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 94.1 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 97.2 | |

| ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | 97.0 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 97.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, M.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Hu, J. Dual-Branch Network for Video Anomaly Detection Based on Feature Fusion. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244022

Huang M, Li J, Sun Z, Hu J. Dual-Branch Network for Video Anomaly Detection Based on Feature Fusion. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244022

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Minggao, Jing Li, Zhanming Sun, and Jianwen Hu. 2025. "Dual-Branch Network for Video Anomaly Detection Based on Feature Fusion" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244022

APA StyleHuang, M., Li, J., Sun, Z., & Hu, J. (2025). Dual-Branch Network for Video Anomaly Detection Based on Feature Fusion. Mathematics, 13(24), 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244022