1. Introduction

Rare-event phenomena such as emerging disease outbreaks, earthquakes, and industrial defects are typically characterized by extremely low probability of occurrence. The estimation of binomial proportions for such events poses significant challenges, particularly due to the inadequacy of conventional confidence interval methods. Classical approaches, such as the Wald interval, frequently perform poorly for these events due to their reliance on asymptotic normality, which fails as the true proportion approaches the extreme boundaries of the binomial proportions [

1,

2]. The Clopper–Pearson interval also tends to be overly conservative, thus producing wide intervals that result in statistical inefficiency [

3]. Conversely, asymptotic approximation methods such as the Wald interval may yield substantial under-coverage probabilities when the event probability is small [

2].

To address the weaknesses of the traditional confidence interval estimations under rare-event conditions, many frequentist alternative approaches [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] and Bayesian alternatives [

10,

11] have been proposed. Although these methods have demonstrated improvements in coverage probability, especially in small samples or extreme and rare events, they are built under the assumption of a fixed error margin, which is not plausible for events with proportions at the extreme ends of the probability spectrum (0 and 1). This is because such margins fail to scale with the magnitude of the proportion being estimated, which may lead to under- or overestimated uncertainties, depending on the location of the proportion within the parameter space [

12]. This results in inaccurate estimates because the intervals are either too wide to be practically useful or too narrow to be valid, depending on the sample size and the rarity of the event [

13].

The incorporation of adaptive margins that scale with the magnitude of the proportion into existing classical methods has greatly improved the accuracy of both the coverage probability and the interval width of rare events [

13]. Although alternative adaptive Bayesian methods—such as the adaptive Huber’s ε-contamination model, which assumes that the error margin (ε) is unknown and then adaptively estimates—have been shown to perform well in estimating probabilities on a continuous scale, they tend to underperform in small-sample or rare-event scenarios [

14]. Bayesian adaptive prior methods have also been proposed and shown to perform well in rare events, but they require correct scale parameter tuning, as they may increase the credible width when incorrectly tuned or specified [

15]. As an alternative, we introduce an adaptive Bayesian variance-blending calibration framework (hereafter known as the blended approach or method).

The proposed method offers several key advantages. It significantly improves coverage accuracy by integrating information from the Beta distribution via Jeffreys’ prior, the Wilson score, and a credible-level tuning parameter, as well as a gamma regularization parameter which enables the targeted nominal coverage to be maintained more efficiently across a wide range of sample sizes and true proportions. The use of the Beta distribution and logit transformations stabilizes estimates near the extremes; thus, our method is robust for small sample sizes and extreme proportions near 0 or 1, which provides more accurate and stable intervals. Additionally, by combining multiple sources of variability, the approach avoids overly conservative or overly optimistic interval widths, resulting in intervals that are reasonably narrow without sacrificing coverage. The method, therefore, strikes an optimal balance between precision and coverage. The incorporation of the gamma and the credible level parameters allows the intervals to adapt to the sample size and true proportions, which accounts for sampling uncertainty and potential overdispersion. Computationally, the proposed method is fully vectorizable and memory-efficient, thus enabling seamless integration into automated workflows and statistical software. Furthermore, its modular structure allows for rapid diagnostics and tuning, facilitating iterative refinement without computational bottlenecks.

This paper makes contributions to the statistical theory of estimation by introducing a blended confidence interval method that inherits asymptotically desirable properties (consistency, efficiency, and asymptotic normality) of frequentist and model-based inferences. Specifically, as

n → ∞, the proposed interval exhibits consistency, asymptotic normality, and nominal coverage probability. The blending mechanism is theoretically grounded in logit-scale transformations and adaptive variance blending, ensuring that the method remains robust for small samples and across extreme events. Furthermore, this paper makes practical contributions in that the method is robust and adaptive to extreme and rare events, as well as a small sample size. It also yields high coverage with conservative width, thus making it more adaptable to problems in various fields and applications. The rest of the paper is outlined as follows. The theoretical framework is presented in

Section 2, while the simulation design is described in

Section 3. The results and discussion are then provided in

Section 4, and the paper concludes with a summary in

Section 5.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this section, we provide details of the traditional Bayesian interval estimation approach and then extend it to an adaptive version by incorporating our proposed margin correction and variance blending method. We also provide the methodology for the Wilson approach as well as methods for assessing the performances of the three methods. Accurate interval estimation for binomial proportions is fundamental in statistical inference. Bayesian methods offer probabilistically coherent intervals that are derived from the posterior distribution. For binomially distributed data, Bayesian updating with conjugate Beta priors yields Beta-distributed posteriors, thus enabling straightforward computation of credible intervals. However, traditional credible intervals may be too conservative or too narrow, especially for small samples with extreme proportions. To address this, we introduce a blended variance calibration framework that incorporates a tuned credible level within a Bayesian framework to enable adaptive uncertainty quantification.

2.1. Standard Bayesian Credible Interval Using the Beta Distribution and Jeffreys’ Prior

Consider a sample size n (number of trials) and number of successes k, where and p, the true underlying success probability. The goal is to estimate using our proposed method, the standard Bayesian method with Jeffreys’ prior, and Wilson score interval.

2.1.1. Formulation

Assume that

p follows the prior distribution of Jeffreys’ [

16], such that

By denoting

and

, with a credible level

, then the

credible interval is defined by Equation (2) as

where

is the inverse CDF (percent point function) of the Beta distribution. Given the posterior mean and the variance of the

as

we define the credible width as

This is a quantile-based width and, although it narrows as n → ∞, it does not scale directly with the posterior variance. Quantiles reflect cumulative distribution and not local spread. Therefore, the standard Bayesian and the Jeffreys’ interval shrink as sample size increases but do not scale proportionally with the posterior variance; hence, their quantile spreads are fixed. The analysis below explains why the standard Bayesian credible interval width does not scale proportionally with variance.

2.1.2. Non-Proportionality Scaling of the Bayesian Credible Width with Variance

Let the quantile function

be implicitly defined as

The definition in Equation (5) suggests that

is the value such that the cumulative distribution function (CDF) equals

q, i.e.,

. Using the chain rule,

However, since

, substitution leads to

. Therefore

Substitution of Equation (7) into Equation (5) yields

Now, let

be the central quantile and

be a

interval; the lower and upper quantiles are respectively defined by

. Let the interval width be denoted by

. Using a first-order Taylor expansion, it can be shown that

Therefore, by substituting the quantile derivative, the interval width becomes

From the quantile derivative in Equation (8)

The implications are that near the boundaries (0 and 1), the quantile function becomes extremely sensitive to small changes in q, especially when a < 1 or b < 1, which leads to distorted interval widths in the tails. Therefore, width behaves nonlinearly, especially at the boundaries. This explains why the intervals stretch in the tails and the width does not scale proportionally with variance.

2.2. Wilson Score Interval

Given the Z-score

, the confidence level

, and

, where

k and

n are previously defined, then the Wilson score interval [

2] is formulated as

2.3. Adaptive Bayesian-Logit-Scaled Variance-Blending Calibration Framework

Here we present a detailed formulation of our proposed method. We then prove its width’s proportionality to the margin of error and how the margin of error also adapts to the sample size. We further assess the asymptotic properties of the method.

2.3.1. Formulation

Using the Jeffreys’ Beta posterior prior [

16], we transform the lower and the upper confidence limits by first scaling it such that

where

is the credibility multiplier representing the coverage level, and it determines how wide the interval is based on the desired confidence level. It therefore serves as a regularization parameter, and it allows the calibration (via optimization) to shrink extreme intervals to stabilize the estimates. Now let us transform the interval on a logit scale as follows,

The center and the half-width are computed as

Definition 1. Given the sample variance, model-based variance, and the Wilson variance approximation defined bythe blended variance and the corresponding standard error are given bywhere is a correction factor that prevents division by zero. Now, substituting the blended standard error in Definition 1 into the half-width in Equation (12) yields the adaptive margin of error in Equation (13) below.

We now adjust the logit interval on the probability scale to obtain the credible interval as

It is observed in Definition 1 that the blended variance assumes an additive structure without explicit weights. The additive structure of the blended variance is rooted in decision-theoretic principles and variance decomposition under quadratic risk. In classical risk frameworks, particularly under squared-error loss, the total risk is expressed as the sum of independent variance components, where each represents a distinct source of uncertainty [

17,

18]. This additive property ensures interpretability and coherence because each term contributes proportionally to the overall uncertainty without requiring complex interactions. Introducing explicit weights would necessitate estimating additional hyperparameters, which increases computational complexity and introduces potential instability, especially in small samples where parameter estimation is inherently noisy. Weighted schemes also risk overfitting specific scenarios; thus, they reduce generalizability across rare-event regimes. By contrast, the unweighted additive form provides a parsimonious solution that is theoretically justified and empirically robust. Furthermore, asymptotic analysis (see

Section 2.3.3) confirms that all components decay at a rate O(1/n), which ensures that none of the sources dominate as the sample size grows. This property aligns with minimax risk principles thus emphasizing robustness and stability over aggressive shrinkage, which is critical for rare-event inference where under-coverage can have severe consequences.

The variance blending technique integrates frequentist variance decomposition, Bayesian regularization, and decision-theoretic risk aggregation [

2,

17,

18,

19]. Each component serves a unique role in addressing limitations of traditional interval estimation methods. The sampling variance captures uncertainty inherent in binomial data and is derived from the Fisher information on the logit scale. Its magnitude increases near the boundaries of the parameter space (0 or 1) and in small samples, thus reflecting the heightened variability in these situations. The gamma regularization term introduces a prior-informed penalty that stabilizes estimates when data are sparse or proportions are extreme. This term acts as a safeguard against erratic behavior by damping excessive variability. However, its influence diminishes with increasing sample size, thus preserving asymptotic efficiency. The Wilson margin penalty complements these adjustments by correcting for skewness and boundary effects which ensures conservative interval widths in low-proportion regions where classical methods often fail. Together, these components provide a balanced framework that adapts dynamically to sample size and proportion, hence mitigating distortions without sacrificing efficiency.

Regularization within the blended variance is further enhanced through credible level tuning, which optimizes the trade-off between coverage probability and interval width. This adaptive calibration ensures that intervals remain sufficiently wide to maintain nominal coverage in rare-event scenarios while avoiding unnecessary conservatism in moderate regimes. The integration of Bayesian and frequentist elements provides dual advantages. While the Bayesian priors stabilize inference near boundaries, the frequentist components maintain desirable asymptotic properties such as consistency and efficiency. Practically, this design offers robustness across diverse applications such as epidemiology, reliability engineering, and early-phase clinical trials, where rare events and small samples are common.

The credible interval constructed in Equation (14) is built on several key assumptions that ensure its theoretical validity and practical relevance. These assumptions include the following:

The observations are sampled from independent Bernoulli trials with a fixed number of trials n and constant success probability p.

Each trial is independent, with no correlation or clustering effects.

The Bayesian component assumes a non-informative Jeffreys’ prior to stabilize inference near boundaries.

Adjusting the credible level within the specified grid (e.g., 98–99.9%) achieves near-nominal frequentist coverage without introducing bias.

Gamma regularization scales with sample size. This suggests that the term acts as a penalty, which stabilizes variance in small samples and diminishes as n grows, thus preserving asymptotic efficiency.

Transforming the intervals to the logit scale is assumed to improve numerical stability and symmetry near extreme proportions.

The sampling variance, Wilson margin penalty, and Gamma regularization are assumed to combine additively without violating consistency or efficiency.

For large sample sizes, the method assumes convergence to normality on the logit scale, thus ensuring consistency and efficiency as n → ∞.

2.3.2. Proportionality Scaling of the Credible Width with the Variance

Let

, the lower bound:

, and the upper bound:

; then

. The Beta quantile function

is implicitly defined as

Applying first-order Taylor expansion to Equation (15) yields

The quantile derivative function is obtained as

Therefore, after the substitution of

, the width in Equation (12) becomes

Equation (18) implies that the width is proportional to

, thus increasing

reduces the interval width linearly. To further show that the width is proportional to the posterior variance, we transform the interval to logit scale by letting

The application of the first-order Taylor expansion to

yields

where at

and

Therefore, by the substitution of

and

, the width on the logit scale becomes

By the definition of margin of error, our adjusted margin of error on the logit scale becomes

From Equation (21), the logit-scaled half-width is inversely proportional to (tail probability), hence it scales proportionally to the asymptotic variance or the uncertainty.

2.3.3. Asymptotic Properties

The margin of error of the Jeffreys’ prior (through the Bernstein–von Mises theorem), the model-based method, and the Wilson method are asymptotically normal, efficient, and consistent. Therefore, by default, our blended method inherits these properties. In the preceding sub-sections, we assess these properties to establish the underlying asymptotic and other theoretical properties of the blended method.

- (a)

Asymptotic efficiency

From Definition 1, the blended variance is obtained as

From this variance, as

, each term behaves as follows: sampling term ~

, Gamma term ~

, and Wilson term ~

. Therefore, following from the Hajek–Le Cam theorem of local asymptotic normality and influence functions [

20],

as

. Furthermore

, hence

which implies that the subsequent interval width shrinks at rate

, thus confirming asymptotic efficiency.

By the weak law of large numbers, let

Therefore, for any

,

Furthermore, since we have shown that

as

,

is differentiable, and Lipschitz on (0, 1), then

where

,

, and

. Thus, the interval converges to the true population proportion as

.

Since

in probability and

, the numerator

behaves like the mean of an

i.i.d. terms (via beta posterior), so, by the central limit theorem,

. Hence,

This confirms asymptotic normality in logit space. From the blended variance definition 1, it can be shown from leading order analysis that

Therefore, following from the asymptotic normality of the observed

,

If we let

and

, then by the delta method, if

, then

From the results in Equation (27), the unscaled interval limits exhibit asymptotic normality that converges in distribution to normality. This implies increasing concentration around the true parameter p as the sample size grows. This classical form of asymptotic behavior confirms the consistency of the interval bounds and validates their use as efficient estimators. Moreover, it highlights that confidence intervals become progressively narrower and more accurate in large samples, reinforcing the appropriateness of normal approximations for inference, particularly in transformed parameter spaces such as the logit scale.

3. Simulation Design

3.1. Parameters and Design

Let denote the number of observed successes in a binomial trial of size , with estimated proportion , where is the true binomial probability. For each combination of and , we perform M simulation replications following burn-in samples B. Each replication consists of a Bernoulli trial with Jeffreys’ prior-based posterior inference and three interval construction methods.

For each and a combination of k and n

Step 2: Compute the posterior shape parameters for the Jeffreys’ prior

Then, construct central

posterior interval as

Step 3: Given , construct the Wilson interval score as follows.

First the center and the margin are calculated, respectively, as follows:

Then, construct the interval as

Step 4: Construct the lower and upper bounds for the Logit margin of error. Using Jeffreys’ prior, compute the lower and upper bounds as follows:

Then, transform the bounds to logit scale as indicated below

Note that at each iteration,

is tuned as indicated in

Section 3.2.

Step 5: Computing the coverage probability and the credible width.

At each iteration

M in Steps 2 to 4, calculate the coverage probability and width as follows:

where

is the indicator function defined by

and

,

represent the corresponding lower and upper credible intervals for each of the interval estimation methods.

3.2. Tuning Procedure

The tuning process aims to strike a balance between achieving high coverage (at least 95%) and maintaining interval efficiency by minimizing width to ensure precise estimates without sacrificing coverage. To achieve this balance, the algorithm evaluates candidate confidence levels through simulation and then selects the credible level that meets the coverage threshold while producing the narrowest or optimal intervals. The tuning process is discussed below in detail.

Step 1: Defining the grid for the credible levels

The algorithm begins by specifying a set of candidate credible levels (), which represent the confidence level used in the Bayesian component of the blended interval. The grid typically spans from 0.98 to 0.999 in small increments, i.e., .

Step 2: Simulations of blended intervals for each credible level

For each candidate level

in the grid, perform Monte Carlo simulation with N = 6000 trials. In each trial, generate a binomial sample of size

n with success probability

and then compute the blended confidence interval as discussed in Step 4 of

Section 3.1. This step evaluates how well each candidate level performs under repeated sampling.

Step 3: Computation of the width for each simulation

For each candidate level , calculate the width by subtracting the lower bound from the upper bound.

Step 4: Selecting Optimal Level

Choose the level

that satisfies:

This ensures the interval is both accurate (coverage ≥ 95%) and as narrow as possible.

NB: After selecting , the algorithm performs a quick validation with 500 trials. If the coverage falls below 0.95 during this check, it overrides the tuned level with a fixed value of . Because simulations can occasionally underestimate variability, especially in edge cases such as small sample sizes or extreme probabilities, the override rule adds robustness by enforcing a fallback level of 0.985 whenever quick validation shows coverage below 95%. This safeguard ensures that the method remains reliable even under extreme or rare conditions.

For the tuning process, the grid is selected for three reasons. Firstly, the primary goal is to achieve at least 95% coverage, which corresponds to confidence levels near 0.95. Starting the grid at 0.98 allows the algorithm to explore slightly higher levels in case the blended method tends to overcover and produce intervals that are unnecessarily wide. Extending the grid up to 0.999 provides a safety margin for extreme cases, such as very small sample sizes or probabilities near 0 or 1, where higher levels may be required to maintain coverage. Secondly, using small increments (e.g., 0.001) ensures fine resolution for optimization, enabling the algorithm to identify the level that minimizes interval width while meeting the coverage requirement. Large jumps could miss the optimal trade-off between coverage and efficiency. Third, the wide range of levels makes the method adaptable across different scenarios, as coverage and width vary significantly with sample size and true probability. For example, large samples stabilize coverage near 0.95, while small samples or extreme probabilities often require higher levels to avoid under-coverage. Finally, the range from 0.98 to 0.999 strikes a balance between accuracy and computational feasibility. It is broad enough to capture variability across different situations but narrow enough to keep the grid search practical. In summary, this grid ensures flexibility, precision, and robustness in tuning the blended method for diverse data situations.

3.3. The Choice of Gamma

The gamma regularization parameter was introduced to stabilize variance estimates in small samples and near-boundary proportions. Its calibration follows an inverse relationship with sample size, ensuring that the penalty diminishes as n grows, thereby preserving asymptotic efficiency. Empirically, gamma can be tuned through grid search across simulation regimes to minimize coverage deviation from 95% while controlling interval width. However, this approach may result in an inadequate gamma value being selected because it optimizes based on empirical performance in a finite simulation set, which may not fully represent all real-world scenarios; thus, in this study, we fixed gamma at 1. The choice of this value is considered optimal because of how it interacts with the blended variance components and the asymptotic properties. The choice balances stabilization and flexibility and has theoretical justification.

The gamma acts as a penalty term to prevent instability in small samples or near-boundary proportions; hence, if gamma < 1 (too small), the regularization effect is weak and the interval width may shrink excessively in ultra-rare events, leading to under-coverage, while on the other hand, if gamma > 1 (too large), the penalty dominates, which makes the interval unnecessarily wide and conservative, thus reducing efficiency. Gamma = 1 provides an ideal scaling factor that neither inflates nor deflates the blended variance disproportionately, thus ensuring that the regularization term contributes meaningfully without overshadowing the sampling variance or Wilson margin. Furthermore, Gamma = 1 aligns with the principle of unit-information priors in Bayesian regularization, where the penalty corresponds to one “pseudo-observation,” which keeps the method asymptotically unbiased and efficient. In particular, if gamma > 1, the penalty term becomes larger than 1/n; thus, it effectively adds the influence of multiple pseudo-observations, which makes the intervals overly conservative. On the other hand, if gamma < 1, the penalty term is less than 1/n; thus, it contributes less than the equivalent of one pseudo-observation, which may fail to provide sufficient stabilization in small samples. This is specifically consistent with Bayesian decision theory, as it aligns with the principle that priors should reflect minimal but meaningful information, thus ensuring coherent inference across different sample sizes.

4. Results and Discussion

The goal of this section is to estimate the binomial proportion p using our proposed adaptive method to improve coverage and precision of p for rare and extreme events. The chosen ranges of true proportions (0.00001–0.99999) and sample sizes (5–10,000) were selected to reflect realistic conditions encountered in rare-event and extreme-probability scenarios across multiple fields. Ultra-rare probabilities such as 10−5 or smaller occur in safety-critical engineering and pharmacovigilance, where failure rates or adverse events are extremely low. Rare disease prevalence often falls between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 1,000,000, which aligns with the lower bound of our range, while proportions near 0.99999 represent high-reliability systems or near-certain outcomes in reliability studies. The sample size range of 5 to 10,000 captures both ends of practical study designs. For example, early-phase clinical trials and rare-disease studies often enroll fewer than 50 participants, sometimes as few as 12, whereas large-scale epidemiological surveys and public health programs routinely include tens of thousands of individuals to detect low-prevalence conditions. This broad range ensures that the proposed method is evaluated under different proportions that are representative in healthcare, pharmacovigilance, behavioral sciences, and reliability engineering. Rare disease prevalence thresholds and ultra-rare definitions (≤1 per 1,000,000) are outlined in Orphanet (a European database for rare diseases and orphan drugs) and in European Medicines Agency guidelines. In reliability engineering, standards often target failure probabilities as low as 10−5 to 10−6. Similarly, survey designs from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention typically require sample sizes exceeding 10,000 to capture low-prevalence conditions.

4.1. Simulation Results

We simulate 5000 samples, where the first 1000 are used as burn-in samples to estimate proportions of rare and extreme events using our method and then compare its performance to Wilson and Jeffreys’ prior in terms of coverage probability and precision. Detailed R code used for the simulations, along with practical applications and the datasets, are provided as

Supplementary Material. Refer to the

Supplementary Material section following

Section 5 for additional details.

4.1.1. Coverage Consistency

Across all regimes, from ultra-rare to extreme, the intervals of our blended method consistently maintain coverage probabilities close to or exceeding the nominal 95% level. This is especially evident as sample size increase, where the blended method often matches or surpasses both the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals. For instance, at

p = 0.00001 and

n = 10,000, the blended interval achieves 99.18% coverage compared to the 90.36% under-coverages for Jeffreys’ and Wilson. Even in extreme tail scenarios (e.g.,

p = 0.99999), the blended method maintains coverage above 95% at moderate to large

n, demonstrating robustness under boundary conditions. Jeffreys’ intervals tend to underperform at small

n and extreme

p, while Wilson intervals maintain coverage but are often overcompensated with wider bounds. The results are visualized in

Figure 1, where the blended method tends to consistently stay near or above the 95% coverage probability.

4.1.2. Interval Width and Efficiency

In

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 2, it is observed that the blended intervals tend to be wider at very small sample sizes (e.g.,

n = 5 to 10), which is expected due to the added gamma penalty and conservative tuning of the credible level. However, these widths remain practical and shrink rapidly as the sample size increases. At all levels, the blended intervals are competitive compared to both the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals while preserving high coverage. For instance, at

p = 0.001 and

n = 5, the blended interval width is 0.46856, compared to 0.38069 for Jeffreys’ and 0.43544 for Wilson, while at

n = 10,000, for the same proportion, the blended interval width is 0.00463, compared to 0.00390 for Jeffreys’ and 0.00391. This improved efficiency while maintaining high coverage reflects the adaptiveness of the blended method, which balances precision and coverage through dynamic tuning and variance blending.

4.1.3. Impact of True Probability (p)

At low true probabilities (e.g., p = 0.00001 to 0.001), the blended intervals outperform the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals in coverage with completive width as the sample size increases. Jeffreys’ occasionally fails to capture the true value with conservative width at small n due to its symmetric prior, while the Wilsons interval also fails to maintain the nominal coverage but with relatively smaller width. Our method, by contrast, adapts to the rarity of the event, ensuring that the interval expands appropriately to maintain coverage without excessive conservatism. As p increases to moderate levels (e.g., 0.05), all methods perform well, but the blended interval remains conservative with the interval width. At high p (e.g., 0.99 and above), the blended method continues to excel, yielding conservative intervals, and maintains coverage even when Jeffreys’ interval begins to under-cover.

4.1.4. Sample Size Sensitivity

Smaller sample sizes (

n = 5, 10) exhibit more variability and wider intervals across all methods, as seen in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 and

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. However, the blended approach maintains high coverage even for small sample sizes, which indicates robustness in small-sample data. For example, at

p = 0.01 and

n = 10, the blended interval achieves 99.62% coverage with a conservative width of 0.33358, thus outperforming the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals because of their under-coverages. As sample size increases (

n ≥ 100), all methods stabilize, but the blended interval consistently maintains coverage above the nominal while maintaining conservative or narrower width. This scalability confirms that the method remains efficient across sample sizes and is particularly well-suited for large-sample studies or simulations. Notably, the blended interval avoids the erratic discreteness-induced jumps seen in classical intervals when

n is small, which is one of the strengths of the blended method.

4.1.5. Sensitivity and Robustness of the Tuning Parameter on Performance

Coverage Calibration: The credible level is highly responsive to the interaction between sample size and true proportion. For ultra-rare events (e.g., p = 0.00001), the method consistently selects high credible levels (e.g., 99%) to compensate for data sparsity and ensure the interval expands sufficiently to include the true value. For instance, at p = 0.00001 and n = 5, the credible level is 0.985, yielding 100% coverage with a width of 0.49251. Similarly, for p = 0.0001 and n = 10, the level increases to 0.99 while maintaining full coverage. As the sample size increases or the true proportion becomes moderate, the tuned level decreases. At p = 0.00001 and n = 1000, the level drops to 0.98, still achieving 98.88% coverage with a much narrower width of 0.00334. For p = 0.001 and n = 5, the credible level is 0.98, and the method achieves 99.38% coverage with a width of 0.46856. This dynamic tuning allows the method to self-correct, i.e., if initial tuning results in under-coverage, the algorithm escalates the level to 98.5% or higher to restore coverage. This adaptivity underpins the method’s robustness across regimes where fixed-level intervals often fail.

Width Efficiency: Higher credible levels yield wider Bayesian bounds, which, after transformation and blending, produce more conservative intervals. The tuning algorithm balances this trade-off by selecting the credible level that still achieves the desired coverage. This ensures statistical efficiency by avoiding unnecessarily wide intervals. This behavior is evident across

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. For example, at

p = 0.00001 and

n = 1000, the credible level is 0.98, producing a narrow interval (width = 0.00334) with 98.88% coverage. At

p = 0.0001 and

n = 10000, the level remains at 0.98, yielding 98.02% coverage with a width of 0.0005. For rare events like

p = 0.001 and

n = 10, the level remains at 0.98, producing an interval width of 0.27732 and 99.34% coverage. These examples illustrate how the method maintains conservative width while preserving or exceeding the target coverage.

Boundary Sensitivity: Near the boundaries (p ≈ 0 or p ≈ 1), credible level tuning becomes more aggressive. The logit transformation amplifies small differences near the extremes, necessitating wider initial bounds. For instance, at p = 0.99999 and n = 5, the credible level is 0.985, yielding 99.98% coverage with a width of 0.49256. At p = 0.999 and n = 100, the level is also 0.98, producing 99.58% coverage with a width of 0.03467. The gamma penalty and Wilson variance blending help stabilize the interval, but the credible level remains the primary mechanism for controlling coverage.

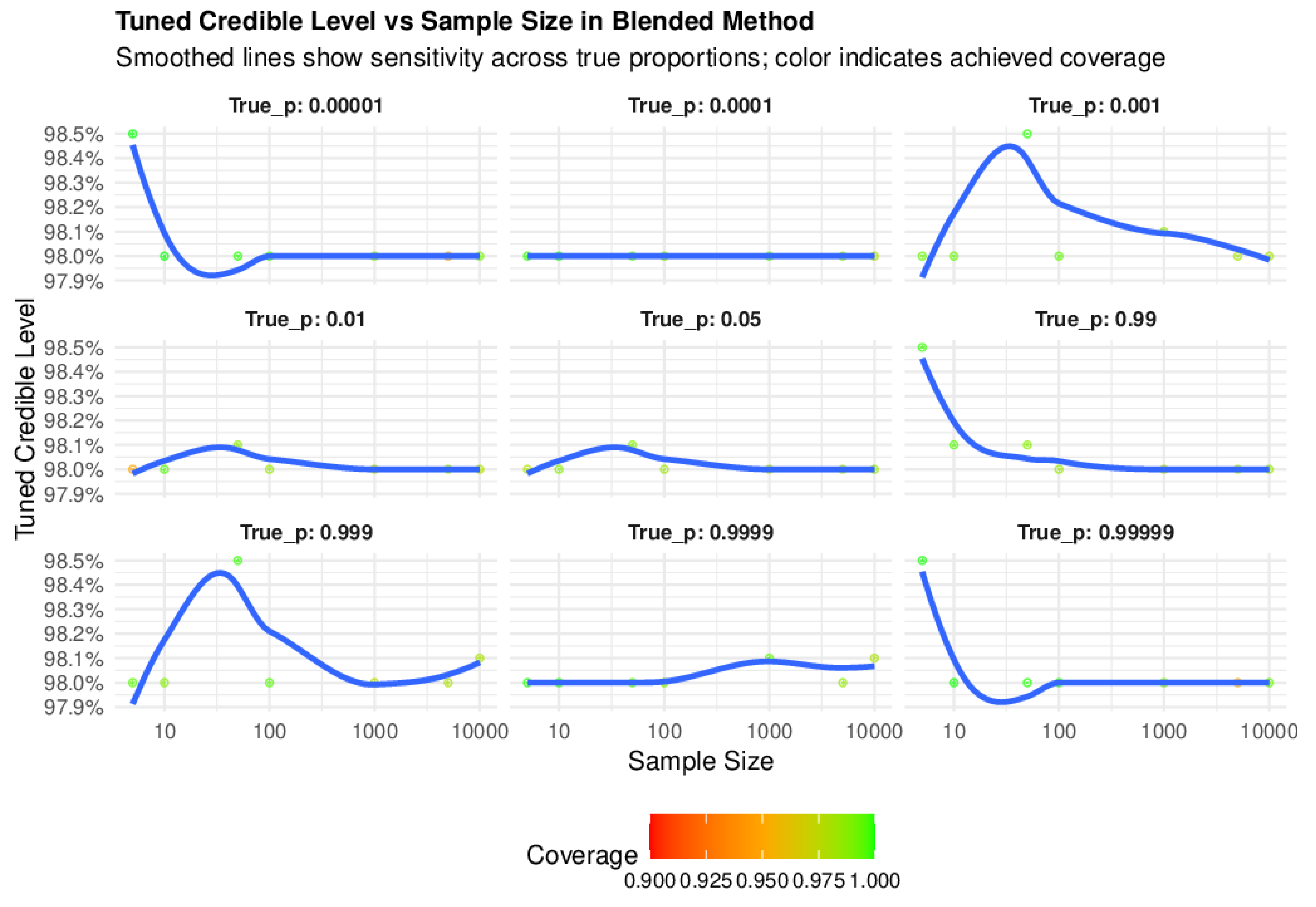

The multi-panel plot in

Figure 3 illustrates how the blended method dynamically tunes credible levels across extreme binomial regimes, balancing robustness and sensitivity. For ultra-rare and near-certain proportions (e.g.,

p = 0.00005 or

p = 0.99999), the credible level starts conservatively high at small sample sizes around 98.5% which ensures robustness against under-coverage. These tuning curves show steep initial declines that flatten as sample size grows, forming arcs that transition from convex to nearly linear beyond

n ≈ 100. This curvature reflects logit-scale transformation effects, where differences near boundaries are amplified, causing higher credible levels at low

n. In contrast, mid-range proportions (e.g.,

p = 0.05) exhibit gentle slopes and early stabilization near 98%, indicating less aggressive tuning and geometric smoothness. The plot confirms symmetry across complementary proportions (e.g.,

p ≈ 0.001 vs.

p ≈ 0.999), reinforcing the method’s principled adaptiveness. Collectively, the steepness at extremes, flattening at large

n, and mirrored trajectories demonstrate how the method maintains high coverage while adaptively reducing credible levels from 98.5% at

n = 5 to 98% at

n ≥ 10,000 independent of fixed parameterization.

4.2. Practical Applications Using COVID-19 Data

To assess the performance of the blended method in comparison to the competing methods with applications to real life data, mortality and recovery rate data for the COVID-19 outbreak was used. Data from nine countries—Western Sahara, Ghana, South Africa, Australia, Brazil, Germany, France and the USA—were used. These data were selected to mirror rare, extreme nature, or small sample applications. We focused on mortality and recovery rates because they represent opposite extremes of the proportion spectrum in COVID-19 data. Mortality rates are typically low (often <0.01), making them rare-event scenarios that challenge conventional interval estimation methods. In contrast, recovery rates often approach near certainty (>0.99), placing them at the upper extreme of the probability scale. Evaluating these endpoints allows us to demonstrate the adaptability of the proposed method across the full range of binomial proportions from ultra-rare to near-certain outcomes. The data were sourced from

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 26 August 2025). For each country, mortality and recovery rate were estimated using the blended method and the competing methods. The results are reported in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Table 5.

Performance of interval estimation methods for COVID-19 mortality rates.

Table 5.

Performance of interval estimation methods for COVID-19 mortality rates.

| Country | Sample

Size | True p | Jeffreys’ Coverage | Wilson

Coverage | Blended

Coverage | Jeffreys’

Width | Wilson

Width | Blended

Width |

|---|

Western

Sahara | 10 | 0.10000 | 0.98733 | 0.92967 | 0.98733 | 0.34371 | 0.36878 | 0.40912 |

| Ghana | 171,889 | 0.00851 | 0.94733 | 0.94633 | 0.97900 | 0.00087 | 0.00087 | 0.00103 |

| South Africa | 4,076,463 | 0.02517 | 0.94633 | 0.94633 | 0.97700 | 0.00030 | 0.00030 | 0.00036 |

| Australia | 11,853,144 | 0.00206 | 0.94550 | 0.94500 | 0.97717 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 0.00006 |

| Brazil | 38,743,918 | 0.01836 | 0.94983 | 0.94983 | 0.97833 | 0.00008 | 0.00008 | 0.00010 |

| Germany | 38,828,995 | 0.00471 | 0.94933 | 0.94933 | 0.97800 | 0.00004 | 0.00004 | 0.00005 |

| France | 40,138,560 | 0.00418 | 0.95283 | 0.95283 | 0.98100 | 0.00004 | 0.00004 | 0.00005 |

| USA | 111,820,082 | 0.01091 | 0.95050 | 0.95050 | 0.97850 | 0.00004 | 0.00004 | 0.00005 |

Table 6.

Performance of interval estimation methods for COVID-19 recovery rates.

Table 6.

Performance of interval estimation methods for COVID-19 recovery rates.

| Country | Sample

Size | True p | Jeffreys’ Coverage | Wilson

Coverage | Blended

Coverage | Jeffreys’

Width | Wilson

Width | Blended

Width |

|---|

Western

Sahara | 10 | 0.77778 | 0.98600 | 0.92683 | 0.98817 | 0.34513 | 0.36977 | 0.41099 |

| Ghana | 171,889 | 0.90000 | 0.95467 | 0.95317 | 0.98033 | 0.00087 | 0.00087 | 0.00103 |

| South Africa | 4,076,463 | 0.99148 | 0.95150 | 0.95150 | 0.98000 | 0.00038 | 0.00038 | 0.00045 |

| Australia | 11,853,144 | 0.95978 | 0.95267 | 0.95267 | 0.97750 | 0.00015 | 0.00015 | 0.00007 |

| Brazil | 38,743,918 | 0.93561 | 0.95067 | 0.95067 | 0.98183 | 0.00004 | 0.00004 | 0.00018 |

| Germany | 38,828,995 | 0.99529 | 0.95733 | 0.95717 | 0.98083 | 0.00004 | 0.00004 | 0.00005 |

| France | 40,138,560 | 0.99582 | 0.95067 | 0.95067 | 0.97900 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 |

| USA | 111,820,082 | 0.98206 | 0.98600 | 0.92683 | 0.98050 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 0.00006 |

Across countries, the mortality rate intervals for the blended method consistently achieved better coverage, particularly in large samples and extremely low rates. For example, for Australia (true proportion = 0.00206), blended coverage reached 97.7%, exceeding the nominal 95% threshold and outperforming the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals. Similar patterns were observed for South Africa and Germany, where the blended intervals maintained coverage above 97%. Although the width was comparatively wider in most cases, the blended method’s prioritization of coverage over smaller width appears justified in rare events where underestimation poses substantial epidemiological risk. In small samples such as Western Sahara (n = 10), the blended intervals preserved high coverage (98.7%) while producing competitive interval width in comparison to the other methods. Jeffreys’ intervals remained stable, whereas Wilson intervals exhibited under-coverage (92.9%), indicating sensitivity to small-sample-size bias and boundary truncation.

The recovery rate estimation revealed good performance across all methods in large samples. However, blended intervals again maintained coverage above 97% for Brazil and Germany. Interval widths converged across methods in large samples (width ≤ 0.000103), yet the blended intervals retained a marginal advantage in coverage. For the USA (true proportion = 0.98206), Wilson coverage (92.683%) dropped below the nominal threshold, while the blended and Jeffreys’ intervals were above the nominal levels, which underscores the blended method’s robustness near the boundary. The blended method’s adaptive tuning emerged as a key strength. This dynamic behavior enables the method to maintain nominal coverage across heterogeneous epidemiological contexts without excessive conservatism.

In summary, the blended method is the most reliable for coverage, with an under-coverage rate of 1.6% (1 out of 63) compared to that of Jeffreys at 14.3% (9 cases) and Wilson at 12.7% (8 cases). The blended method consistently exceeded the nominal 95% level, even for rare events and boundary extremes. The demonstrated efficiency of the blended interval method in both rare-event and boundary-extreme events supports its integration into public health surveillance systems, particularly for real-time estimation of mortality and recovery rates. Its capacity to preserve coverage in sparse data environments makes it suitable for early disease outbreak detection and low-incidence monitoring, while its stability in high-proportion contexts ensures accurate reporting of recovery rates of disease outbreaks. Adoption of the blended method in reporting frameworks could enhance the interpretability and credibility of epidemiological risks, thus informing risk communication, resource allocation, and intervention prioritization. Moreover, its modular tuning architecture aligns with adaptive surveillance strategies, which allows for calibration sensitivity in evolving epidemic outbreaks.

4.3. Computational Cost Analysis

The proposed method is theoretically bounded by per pair, where is the number of simulation iterations and the number of candidate credible levels in tuning. Our configuration (, , and 63 parameter pairs) results in approximately 1.26 million interval estimations. Despite this complexity, the observed runtime is far below the threshold. The largest configuration was completed in approximately 87.5 s (1.46 min) using about 20.15 MB of memory, while the smaller cases required only about 7.1 s (0.12 min) and 1.75 MB. These results confirm that the implementation is memory-efficient by leveraging R’s optimized linear algebra routines, hence avoiding explicit scaling. Efficiency is achieved through vectorization, sparse operations, and caching, which makes the method practically robust for large-scale application.

4.4. Data-Based Tuning Rules for the Credible Level : The Choice of Adaptive over Fixed Rule

In practice, choosing a single fixed value for instead of using a grid or adaptive rule is not recommended because it removes the flexibility that the method needs to perform well across diverse data conditions. Real-world datasets vary widely in sample size and observed proportion, and a fixed might work for moderate and , but may fail for very small samples or rare events. For example, always using could lead to under-coverage when and or produce unnecessarily wide intervals when and . The strength of the proposed method lies in its ability to adapt interval width to maintain coverage while minimizing unnecessary conservatism; thus, a fixed ignores this adaptivity and makes the method behave like a standard fixed-level Bayesian interval, which defeats the purpose. Coverage performance depends on both and , and without tuning, intervals can fail to meet the nominal 95% coverage in rare-event scenarios, which is critical in applications such as epidemiology or reliability analysis. Practically, using a fixed could result in misleading intervals, either too narrow (under-coverage) or too wide (inefficient), which can lead to incorrect decisions in safety-critical applications like clinical trials or risk assessments.

To address this, we implement a grid search within the range [0.98, 0.999]. Preliminary simulation studies (not reported here) support the choice of this range, which is broad enough to capture variability across regimes yet narrow enough to remain computationally efficient. For practical reasons, searching across the entire (0, 1) spectrum would add unnecessary computational cost without improving results, as most intervals of that range are irrelevant for coverage optimization. Although grid search is implemented within the codes, practitioners may need to specify the range for the grid search to suit the nature of their data for better results; thus, based on the simulation results from

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, the following grid selection rules (as reported in

Table 7) are proposed as a guide.

The algorithm starts at the lower boundary and increases incrementally (e.g., by 0.001) until a coverage ≥ 95% is achieved. This ensures robustness for rare-event scenarios and efficiency for large-sample studies without unnecessary conservatism.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces an adaptive Bayesian variance-blending calibration framework for estimating binomial proportions of rare and extreme events. The performance of the method in comparison with the classical Jeffreys’ and Wilson score intervals across different sample sizes (n = 5 to 10,000) under different true proportions was assessed through extensive simulations and real data applications. The blended method was shown to be robust and adaptive across sample sizes and true probabilities. It consistently achieves or exceeds the nominal 95% coverage, particularly in small sample events, rare events, and extreme events where traditional methods often struggle. Even at small sample sizes (n = 5), the method maintains high coverage and avoids erratic behavior typical of discrete classical intervals.

In terms of interval width, the blended method balances conservatism and efficiency through dynamic credible level tuning. While intervals are wider at small n due to conservative initialization, they shrink rapidly with increasing sample size. At moderate and large n, blended intervals are competitive in comparison to the Jeffreys’ and Wilson intervals while preserving coverage. This adaptivity is driven by a tuning mechanism that adjusts the credible level based on the observed data and empirical coverage feedback. High credible levels are selected for ultra-rare events to ensure efficiency, while lower levels are used for moderate proportions to enhance precision.

Geometric analysis of the tuning curves demonstrates how the blended method adaptively tunes credible levels across binomial extremes by starting at higher values for small samples and gradually flattening into near-linear, symmetric trajectories as sample size increases, thus ensuring robust coverage and balanced sensitivity. These features reflect the method’s ability to stabilize estimates near boundaries through aggressive credible level tuning and variance blending.

Theoretically, the blended method bridges Bayesian and frequentist paradigms by using empirical feedback to calibrate credible levels to guarantee near or above nominal coverage with narrow or conservative width. Its adaptivity and boundary sensitivity offer a competitive alternative to fixed-level intervals, particularly in rare and extreme events. Practically, the method’s ability to adaptively shrink or expand based on sample size and true proportion makes it highly suitable for applications where sample size limitations and rare or extreme event proportions—such as rare disease prevalence, safety-critical system reliability, and early-phase clinical trials—render conventional interval estimation inaccurate. Considering these findings, we recommend the use of the blended method for interval estimation of rare and extreme events, especially when sample sizes are limited or true proportions lie near the boundaries. Future work may extend this framework to multinomial or hierarchical settings, where adaptive tuning could further enhance inference under complex data structures.

Although the proposed adaptive Bayesian variance-blending framework demonstrates strong performance across rare and extreme event scenarios, several limitations remain. First, the method incurs additional computational overhead due to grid-based tuning of credible levels. Although the method is memory-efficient, its runtime can still be significant for very large datasets, which may pose challenges for real-time or large-scale applications in the absence of high computational power and memory.

Second, its performance is sensitive to the tuning of key parameters, such as the credible level. Incorrect calibration can lead to inflated interval widths or under-coverage. Furthermore, the approach assumes independence and that the trials follow a strict binomial form. Finally, while the method was validated using simulations and COVID-19 data, broader empirical testing across diverse domains, such as reliability engineering and rare disease prevalence, is needed to confirm generalizability.

Future research should address these limitations by developing automated tuning algorithms that leverage optimization and reduce computational cost. Extending the framework to handle complex data structures such as multinomial, hierarchical, and correlated models would enhance its application in many fields. In such models, incorporating mechanisms to account for overdispersion, such as beta-binomial or hierarchical Bayesian models, could also further improve robustness. Additionally, adaptive strategies for gamma calibration should be explored to allow dynamic adjustment based on sample size and event rarity, instead of fixing its value to 1. Practical directions include optimizing the method for real-time surveillance systems and creating open-source software implementations to facilitate adoption. Finally, comprehensive validation across multiple application areas will be essential to establish the method’s reliability and scalability.