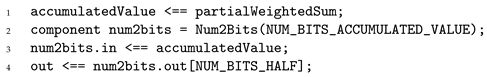

Comparisons between numbers (e.g., “less than” ) are common in general-purpose computation but are nontrivial to express within the R1CS model, which lacks native support for inequalities. As a result, such operations must be encoded using algebraic techniques that translate comparison logic into arithmetic constraints. This section presents and analyzes different strategies for implementing strict comparisons of the form

, where

K is a known constant and

t is an integer input to the comparison. From now on, we represent both

t and the constant

K as 254-bit binary arrays in little-endian format:

where each bit

for all

i. The constant

K is known in advance and is a field element in

, while

t is simply interpreted from its bit decomposition and may lie outside the field range, as long as it fits within 254 bits. Our goal is to construct a minimal R1CS representation that compares the binary input

t against the fixed constant

K and enforces the correct output. This computation is illustrated in

Figure 1, where the output signal is 1 if

, and 0 otherwise.

In

Section 3.2, we introduce the

weighted accumulation algorithm, where we compare

t and

K by computing a weighted sum whose sign indicates the comparison result. The accumulator is built by scanning the bits of

t and

K, and adding or subtracting weighted contributions based on bit differences and their significance. In contrast to the lexicographic method, this approach avoids branching logic, leading to fewer R1CS constraints. However, it introduces two challenges. First, the use of signed values requires extending the representable range beyond the base field

. Consequently, values can no longer be stored as single field elements and must instead be decomposed into smaller chunks, or

limbs, which introduces consistency checks and carry arithmetic, thereby increasing the number of constraints. Second, the accumulator update rules are linear, limiting the algorithm’s ability to leverage the quadratic expressiveness of the R1CS model.

3.1. Lexicographic Approach

The simplest algorithm to determine which of two binary numbers is greater is to identify the most significant bit at which they differ and check which number has a 1 at that position, since that number is the greater of the two. We refer to this strategy as a lexicographic comparison, as it follows the lexical order of bits starting from the most significant position. In conventional computation, this can be easily implemented using a loop that iterates through the bits from the most to the least significant one and terminates at the first differing bit, where the comparison result is established. However, adapting this approach to the R1CS model is not as straightforward, as we show next.

To derive a R1CS for the previous algorithm, we start defining a vector of intermediate signals that indicate whether

t and

K are equal at their bit

i, that is, if

and

are equal. We denote each of these intermediate signals as

and for each bit position

i we set

This equality check can be implemented using the “is zero” check described in

Section 2.1. In particular, to verify whether the bits

and

are equal, we simply check whether their difference

is zero.

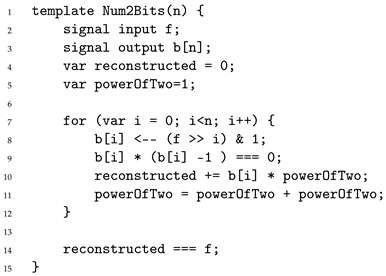

To enforce the correct value of each equality indicator , we use the IsZero() template provided by circom, as shown in Listing 3. This gadget allows us to check whether the bits and are equal by verifying if their difference is zero. Each equality check requires exactly two R1CS constraints, so comparing all 253 bits of t and K results in a total of 506 constraints.

| Listing 3. Forcing the correct value of signals with circom. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i003 Mathematics 13 03959 i003]() |

Each instance of IsZero() in Listing 3 ensures that if , and otherwise. The result of each comparison is stored in the signal z[i].out.

Then, we need to implement decision logic in R1CS to ensure that the comparison output depends on the most significant bit where

t and

K differ. This process starts from the most significative bit and proceeds toward the least significant one. If a differing bit is found, it determines the result; if the bits match, the logic moves on to the next position. To encode this behavior algebraically, we introduce the following constraint over

signals:

where

is an intermediate signal that captures the result of the comparison at bit

i. Specifically,

Observe that, since we are comparing binary values,

can be expressed algebraically as

Since the same logic applies to the subsequent bit positions, we construct a chain of constraints as follows:

In order to define this recursive relation for

, we introduce a new intermediate signal, denoted

, which is defined as

Now, we can transform the above expression in the R1CS form by moving

to the right hand side and grouping terms:

Finally, note that the base case

is directly given by the result of comparing

and

,

and that the final case

is the desired output of our computation:

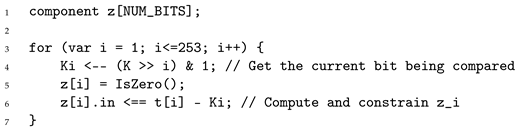

In Listing 4, we show the main loop that directly translates the constraint set we have developed into the circom language.

| Listing 4. Lexicographic approach main loop with circom. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i004 Mathematics 13 03959 i004]() |

Let us now analyze the efficiency of this approach in terms of constraints. First, consider the recursive relation defined for the

values in Equation (

1). For each bit

, enforcing this recurrence requires a R1CS constraint, resulting in a total of 253 constraints. Next, we need to add the constraints that enforce the computation of the equality indicators

across all 253 bit positions. As established in

Section 2.1, each bit requires two constraints, resulting in an additional 506 constraints, so the total number of constraints is

.

We remark that we introduced some extra expressions such as and in the definition of our constraint set. In particular, in the circom listings, we have expressions like the ones listed in Listing 5.

| Listing 5. Some extra linear expressions. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i005 Mathematics 13 03959 i005]() |

However, note that the expressions in Listing 5 are linear constraints that can be simplified and, in fact, are automatically simplified by the

circom compiler [

17]. In summary, because these additional expressions are linear, the total number of R1CS constraints required for the lexicographic comparison in the R1CS model remains 759.

3.2. Weighted Accumulation Algorithm

A more suitable approach for binary comparison in the R1CS model is to iterate over each bit of the two numbers and update an accumulator according to the result of comparing the bits at each position. As we will show next, this approach requires fewer R1CS constraints than the lexicographic method, as it avoids the recursive structure introduced by the decision logic used to locate the most significant differing bit. Instead, it maintains a cumulative quantity that accounts for the comparison. If, at the end of the comparison the accumulated value is negative (i.e., strictly less than zero), then the input number is greater than the constant. Conversely, if the accumulated value is zero or positive, then the input is less than or equal to the constant. Note that when , the comparison output is 1, whereas in our construction, the accumulated value becomes negative. The rationale behind this design choice, which we explain in detail later, is that negative values have a specific bit set to 1, which can then be directly used as the output.

Another important aspect to consider is the value that should be accumulated at each bit position. Since the significance of each bit depends on its position, we cannot add or subtract the same value for all bits. Rather, we need to assign a weight of

to each bit at position

i, reflecting its contribution to the overall numeric value. More formally, let us define a set of functions that operate on each

i-th bit of

t and

K:

where

returns a value based on the bit comparison as shown:

Now, we can define a function

that, given

t, accumulates the weighted contributions:

Next, we define a partial sum function

for

as

It is straightforward to observe that the sum of powers of 2 up to index

j satisfies

Note that this bound is tight in the sense that the sum for the worse case scenario and its upper bound are consecutive integers. Trivially, this leads to the following bounds for each partial sum

:

Now, suppose that

. Then, there exists an index

ℓ such that

, and for all

, we have that

. Additionally, for all

, we have

and at bit

ℓ we have

. This allows us to compute the value of

as follows:

By the bounds on

, we know that

and thus, we can express

as

If

, the function

will be less than or equal to

, thereby establishing the relationship between

t and

K.

However, there is an issue when using this approach in the R1CS model. Recall that in this context we are working over a finite field , where p is a 254-bit prime. To represent negative numbers in a finite field, it is common to split the set of elements into two parts: the first half, , corresponds to positive numbers, and the second half, , corresponds to negative numbers. Note that in this scheme, the most significant bit of each element acts as the sign bit: if it is 1, the number is negative (since these elements lie in the upper part of the range), and if it is 0, the number is positive (corresponding to the smaller values). This is useful in our context, since then, using this sign bit we can obtain the result of the comparison. Specifically, r will correspond to the sign bit of the accumulated value . This also explains why becomes negative when : the accumulation yields a value in the upper half of the field, and therefore the sign bit is set to 1, correctly encoding that t is greater than K.

That said, this representation still comes with a drawback: it effectively halves the number of representable elements. Since the previously defined weighted algorithm needs to add or subtract values up to 254 bits, we must extend the range and operate on 255-bit elements, using the extra bit to encode the sign. Yet, because p is a 254-bit prime, supporting 255-bit arithmetic would require computations modulo , which lies outside our base field . To simulate this larger range, elements must be split into smaller limbs, and additional constraints are needed to ensure that the limb values remain consistent. This significantly complicates the algorithm and increases the overall number of constraints.

Next, we present a more efficient approach than the limb-based method to address the previous problem. The key idea is to update the accumulator using pairs of bits. This increases the number of possible cases per iteration and naturally yields degree-2 constraints that capture pairwise bit comparisons. As a side effect, it also mitigates the overflow issue: processing two bits at a time halves the number of accumulation steps, ensuring that the accumulator remains within the field.

3.3. Addressing Overflow Issues via Pairwise Comparison

To implement processing in 2-bit chunks, we use the following set of functions

which are defined as:

With this formulation, the accumulated value can be computed as

We observe that this method works similarly to the bit-by-bit approach but reduces both the number of accumulator steps (to 127) and the size of the accumulator’s range. More specifically, the values that

can take (when computed as described in Equation (

3)) are integers in the range

to

. These correspond to the extreme cases where all weighted terms are either negative or positive, respectively:

The main advantage of the 2-bit processing method in Equation (

3) is that it naturally keeps the accumulator within the field range, without requiring explicit range checks, simply enforcing the update logic. In our case, the field is defined by a 254-bit prime

p, while the accumulator

only needs to represent

distinct values, including both positive and negative cases. As a result, overflows cannot occur. To handle both signs, we define a convention for interpreting positive and negative values in the field. The most straightforward rule is to consider the first

elements (including zero) as non-negative and the remaining

as negative. For a 254-bit prime, this split gives 253 bits in each direction, more than enough to cover the 127-bit for each sign required by the accumulator.

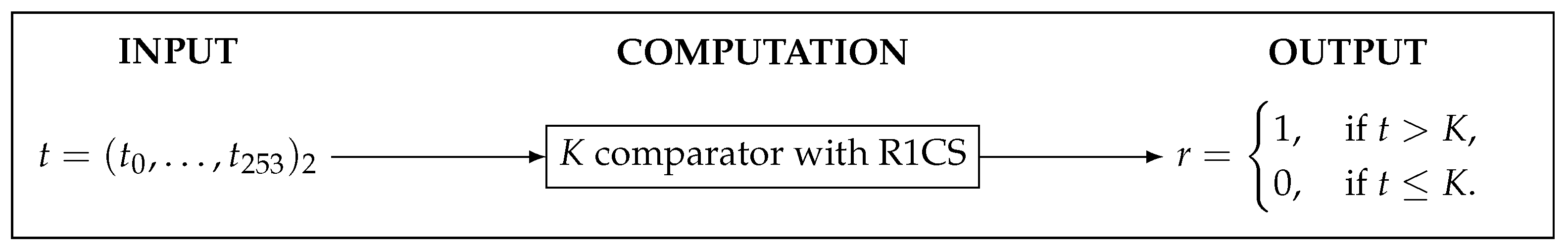

Example 1. Next, we present a numerical example of the weighted comparator using this approach for positive and negative values in the small prime field . The use case we consider is checking whether an input corresponds to the canonical representation of a field element. For our small field, this check is performed using our comparator with , since all canonical representations must be less than or equal to 130. The prime is an 8-bit number, and in this worked example we use the input , which is not a canonical element. Its decimal value is 209, and since , the comparator must output 1. Using the previously described approach for interpreting positive and negative values, the positive elements of are , while the negative elements are , which correspond to in the signed interpretation (yielding the correspondence ).

Figure 2 summarizes the flow of the comparison: from input-bit processing to accumulator update and final sign extraction. In particular, it illustrates how the accumulator processes 2-bit chunks, resulting in 4 update steps. In each step, the algorithm selects a weight from for positive contributions or for negative ones. Under the signed interpretation in , these negative weights correspond to and 123, respectively. To determine how many bits are required to represent the accumulator, we observe its full range in this example. The maximum value, , is obtained by summing all positive weights; the minimum, , results from summing all negatives. Thus, lies in the range , which corresponds (in two’s complement form modulo 131) to the set: Since some accumulator values require up to 8 bits in binary, the final decomposition must be performed over 8 bits to correctly extract the sign. In particular, to determine the sign, we have to inspect the most significant 7th and 8th bits: positive values begin with 00, while negative values begin with 01 or 10. Values whose most significant 7th and 8th bits are 11 cannot appear, as they lie outside the field range and are therefore not representable in .

Although the previous sign-representation approach is feasible, it is inefficient in the R1CS setting. As shown in the previous example, determining the comparison outcome requires a binary decomposition over as many bits as the underlying prime field and inspecting several of the most significant bits. A more efficient alternative is to use a representation in which the sign is encoded in a single, lower-significance bit, as we show next.

Example 2. Following our example, since we need to represent 4-bit positive and negative values, the most suitable representation is modular arithmetic over . In this scheme, values with a 5-th bit equal to 0 are considered non-negative, while those with the 5-th bit set to 1 are interpreted as negative. This allows the sign to be determined from a single bit. For any , the corresponding negative value is its modular complement .

To check whether an input lies in the canonical range of (i.e., ), we apply the same 2-bit processing approach as in Example 1. The accumulator must support values in the range , which fits within 5-bit signed representation. Here, the values 0 to 15 are encoded directly, while to map to 31 down to 16.

Each step adds a signed weight from . Under the modular system, the negative weights appear as , which are significantly smaller than their counterparts under field representation in (previously ), simplifying subsequent computations.

Figure 3 illustrates this optimized design. Although the accumulator updates use 5-bit signed values for the weights, the additions themselves are performed in the field (in this example, ). This mismatch causes no issue: field addition may produce elements requiring more than five bits, but the five least significant bits always coincide with the correct result in 5-bit modular arithmetic, with the fifth bit encoding the sign. In particular, the largest possible field value for the accumulator occurs when all negative weights are added: Note that this maximum value fits in 7 bits, which allows the binary decomposition to operate on 7 bits instead of the 8 bits required by the previous sign representation. While the improvement is small in this example, for a bigger prime field the reduction in required bits becomes substantial, leading to a significant decrease in the resulting R1CS constraint count, as we show next.

We now extend and formalize the approach to our setting which uses a 254-bit prime. In this case, we must represent 127-bit positive and negative values for the weights, so we use modular arithmetic over . Under this representation, the 128th bit acts as the sign bit. A negative value corresponding to a positive integer is therefore given by its modular complement .

Formally, we define the embedding

. This embedding identifies each element

with its canonical image

, thereby forming an embedded subset

. Note that whenever we operate directly on elements

, the operations are performed within the embedded arithmetic, that is, modulo

. In contrast, when these elements are viewed through the embedding as

, the corresponding operations are carried out under the field arithmetic of

, which is our case. The important fact is that, although additions are performed using the field arithmetic in

, when the operands correspond to elements of the embedded subset

, the resulting field element still encodes a consistent operation in the embedded arithmetic

. More specifically, if we add multiple field elements

, we obtain a resulting field element

which can be decomposed as

where

is the reduced result under the embedded arithmetic and

corresponds to the number of operands

representing negative values. In particular, within this representation, the sign of each value derived from operations within the embedded subset

is still determined by its 128th bit, consistent with the semantics of the embedded arithmetic.

Now, we apply the arithmetic to our accumulator. In particular, at each step

i of the 2-bit comparison, we may add either a positive weight

or a negative weight

, which is encoded as

. To make some subsequent equations more concise, we denote these weights as

and define the associated

weight function as

Using this notation, we define the

extended accumulator as the field element representing the sum of all the embedded arithmetic weights at each step:

and, for each

, the corresponding partial sums are

In this setting, the largest possible field element for the extended accumulator occurs when all contributions are negative, yielding the bound

This means that the extended accumulator always remains strictly below

. In addition, the extended accumulator can be decomposed as

where

and

q denotes the number of negative contributions

in the sum defining

. The 128th bit of this quantity encodes the sign in the embedded arithmetic, which directly determines the outcome of the comparison.

3.4. Constraint Definition

In this section we define the constraints that enforce the design presented in the previous section. First, we start with the constraint that enforces the update the accumulator based on the input and constant bits. The first step is to construct a constraint that accurately encodes the weighted function

at each step, enforcing the mapping shown in

Table 1, which lists all possible combinations of input bits

and constant bits

, along with the corresponding output of

.

In this regard, Equation (

5) captures the mapping presented in

Table 1, providing a specification of how the weighted function

is updated at each step of the 2-bit accumulator. Here,

denotes the generalized Kronecker delta function, which is defined as

Each term in Equation (

5) corresponds to one of the four possible combinations of the constant bits

, while the expressions inside the parentheses determine the sign of the output for the corresponding combination of input bits

.

The Kronecker delta functions can be expanded in terms of simple algebraic expressions:

Now, substituting these expressions into Equation (

5) yields a degree-4 polynomial in the variables

, as shown in Equation (

6):

After expanding Equation (

6), we obtain

However, Equation (

7) poses a challenge, as it cannot be directly encoded as an R1CS constraint due to the presence of high-degree terms. In particular, cubic terms must be reduced to quadratic form by introducing an auxiliary variable and an additional constraint for each occurrence. Quartic terms require an even more costly transformation since they must first be decomposed into cubic form by introducing an intermediate variable, and then further reduced to quadratic form through an additional auxiliary variable and constraint. Consequently, representing Equation (

7) in R1CS would substantially increase the number of constraints across all iterations, introducing a significant computational overhead. To address this issue, we leverage the fact that

K is a constant. Then, we can generate a tailored constraint for each possible combination of

and

. More specifically, the equation below enumerates the explicit quadratic form of

for each possible

pair, expressed in terms of the Kronecker functions

.

By substituting and simplifying the algebraic expressions for the Kronecker delta functions, we obtain the following definition for

:

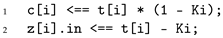

Remark 1. The explanation provided above also sheds light on the generalization to the case where the second operand is not a fixed constant. In our construction, we leverage the fact that K is a constant to tailor the constraint set for the accumulator updates to that fixed value, making each of these constraints quadratic. If the second operand of the comparison is not a constant, all possible update cases, now depending on two fully variable bit pairs, must be captured within a single algebraic relation, namely Equation (7). While feasible, this modification introduces higher-degree intermediate expressions that must be reduced back to quadratic form, resulting in a higher constraint count. For this reason, the variable–constant version remains the most efficient formulation, and the variable–variable extension should be used only when neither operand is known beforehand. The

circom implementation of the previous constraint system can be found in

Appendix A. Next, we describe the main parts of the implementation. The first aspect is that we can use a conditional

if statement when implementing these constraints in a

circom template, so that during compilation, the compiler can select the appropriate constraints for each pair of bits according to the

K value. The

if-else construct in the

circom snippet shown in Listing 6 encodes a conditional weighted function computation, where each branch corresponds to a specific combination of the constant key bits

. By evaluating these bits, the template selects the appropriate algebraic expression for the weighted sum, thereby reproducing the mapping presented in

Table 1. Each iteration of this conditional evaluation is implemented using a single R1CS constraint of degree 2, resulting in a total of 127 constraints for the entire sequence.

| Listing 6. Conditional constraints for weighted factors in circom. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i006 Mathematics 13 03959 i006]() |

Once the individual factors are properly computed and constrained, they are incrementally summed to form the partial weighted sums , as illustrated in Listing 7.

| Listing 7. Incremental accumulation of weighted factors in circom. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i007 Mathematics 13 03959 i007]() |

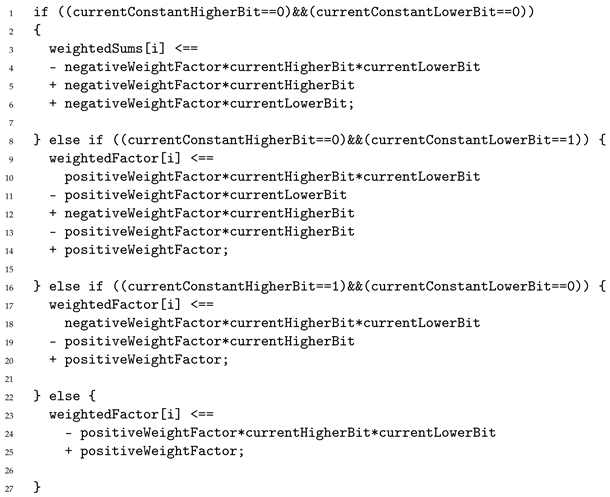

Once the extended accumulated value

has been constructed and properly constrained, the next step is to extract its sign bit, which corresponds to bit position 128. For this purpose, we rely on the

Num2Bits(n) template introduced in

Section 2.2, which enforces that its input is expanded into

n boolean outputs encoding its canonical binary representation. It is essential, however, that the input fits within

n bits, otherwise the template would no longer provide a sound decomposition. A straightforward approach would be to invoke

Num2Bits(254), thereby decomposing

into all bits fitting in the field and directly exposing the sign bit as the output of the comparison. However, such a choice would be unnecessarily costly in terms of constraints.

Instead, we can leverage the bound established in Equation (

4) which guarantees that the extended accumulated value

fits within 135 bits. This observation allows us to invoke

Num2Bits(135) rather than

Num2Bits(254). In addition, none of the signals involved in this decomposition is public, so the reconstruction check can be omitted (as explained in

Section 2.2) and the template contributes exactly 135 constraints. Using

Num2Bits(254) would have generated 254 constraints, so relying on the 135-bit bound yields a reduction of

in this component. Listing 8 illustrates the corresponding

circom code snippet implementing this optimized decomposition and the extraction of the sign bit.

| Listing 8. Extraction of the sign bit from the accumulated value using the Num2Bits() template. |

![Mathematics 13 03959 i008 Mathematics 13 03959 i008]() |

3.5. Soundness Analysis

The pairwise weighted comparator is sound with respect to its specification if the output satisfies if and only if , and otherwise. Concretely, soundness here means that there is no satisfying assignment to the R1CS in which the output deviates from the result of the mathematical comparison: a witness can neither force when nor force when . We now examine the components that ensure this property.

First, for each pair of input bits

and constant bits

, a single R1CS constraint enforces the correct value of the intermediate signal

weightedFactor[i]. As detailed in

Table 1 and Listing 6, each branch of the template corresponds to a different combination of

, and the resulting constraint is designed so that, for all four possible assignments of

, the enforced value of

weightedFactor[i] matches exactly the prescribed weight

of the pairwise comparison. In other words, once the input bits are fixed and assumed boolean,

weightedFactor[i] is uniquely determined and cannot take any other field value without violating the corresponding R1CS equation.

Second, the locally determined weights

are combined through a cumulative sum that defines the extended accumulator

. For each

, we define the partial sums

and the extended accumulator as

. In the implementation, the partial sum is formed incrementally during witness generation, but this does not impose any algebraic relation on its value. The only enforced constraint is the final equality

which uniquely determines the accumulator in any valid witness, since each

is itself uniquely determined. As shown in Equation (

4), the extended accumulator is always bounded by

, well below the field modulus, so all additions occur without wrap-around and no range checks are required.

Third, the

Num2Bits(135) template enforces a unique binary decomposition of

into 135 bits, as recalled in

Section 2.2. Its output therefore coincides with the canonical bit representation of

, ensuring that the 128-th bit is correctly exposed. As shown in

Section 3.3, this bit plays the role of the sign bit in the embedded representation.

Finally,

Section 3.2 establishes the semantic connection between this sign and the comparison result:

implies

, while

implies

.