1. Introduction

The hydrogen atom, characterized by its fundamentally simple structure, has long served as a key model in advancing our understanding of quantum mechanics, providing critical insights into electron-nucleus interactions in various physical, chemical, and biological domains [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Beyond its central role in quantum theory, the hydrogen atom is a valuable platform in quantum information science, enabling the study of bipartite quantum correlations. The spins of the electron and nucleus provide a well-defined Hilbert space for analyzing entanglement, with measures such as two-qubit concurrence and quantum coherence directly related to fundamental constants, including the Planck constant, Boltzmann constant, electron and proton masses, fine-structure constant, Bohr radius, and Bohr magneton. At low temperatures, the hyperfine structure (HFS) states of hydrogen exhibit intrinsic entanglement, which decreases with increasing temperature and vanishes beyond a critical energy threshold of approximately

[

5,

6,

7]. This behavior reflects the sensitivity of entanglement to the interplay between energy splitting and thermal fluctuations. Experimental studies of nuclear-polarized states in hydrogen within solid H

2 films [

5,

8] show departures from the Boltzmann distribution at low temperatures, motivating further exploration of quantum phenomena in these systems.

The electron and nuclear spin degrees of freedom in hydrogen provide a robust framework for investigating quantum correlations and their applications in quantum information science. Previous research on electron-spin dynamics in two-electron double-quantum-dot systems [

9,

10] has highlighted their potential as qubits for quantum information processing [

11,

12,

13]. Similarly, nuclear spins in systems such as nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond are recognized as critical resources for quantum technologies. In contrast to prior studies that examined electron–proton coordinate entanglement [

14] or developed formalisms for HFS entanglement [

15], the present work focuses on the intrinsic hyperfine interaction alone, without including external magnetic fields, providing a clear and consistent framework for analyzing entanglement and steering in this fundamental system.

The concept of quantum steering, introduced by Schrödinger [

16,

17] and later formalized by Wiseman and colleagues [

18], occupies an intermediate position between entanglement and Bell nonlocality. Unlike entanglement, EPR steering is asymmetric, allowing one party (Alice) to remotely influence the quantum state of another (Bob), even when Bob does not trust Alice’s measurement device [

19,

20,

21]. Steering is a key resource for applications such as randomness certification [

22], randomness generation [

23], asymmetric quantum networks [

24], subchannel discrimination [

25], and quantum key distribution (QKD) [

26]. Recent studies have explored relaxing the no-signaling constraint to enhance the efficiency of steering resources [

27].

Investigations of steering and related correlations in dissipative and noisy environments have shown that steering is generally more fragile than entanglement [

28,

29,

30]. However, steering in fundamental atomic systems, such as the hydrogen hyperfine structure, has not been systematically explored. In this work, we investigate the dissipative dynamics of electron–proton correlations in hydrogen atoms, analyzing how steering and entanglement evolve under the influence of environmental decoherence. This setting provides both conceptual and experimental relevance, bridging foundational quantum information concepts with atomic physics. Sequential sharing of steering among multiple observers has been demonstrated using standard projective measurements [

31] or unsharp measurements [

27], and the concept has been extended to multipartite scenarios [

32,

33], illustrating the potential for multi-user quantum networks.

The study of open quantum systems provides a framework for understanding how quantum states evolve under environmental influence, with decoherence playing a central role in degrading coherence, entanglement, and steering—key resources in quantum information processing [

34,

35,

36,

37]. In this work, we model the dissipative dynamics of the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine structure using the Lindblad master equation, allowing a consistent description of Markovian decay processes. By tracking the time evolution of concurrence, quantum steering, and fidelity under different dissipation rates, we characterize the relative robustness of quantum correlations in this naturally occurring bipartite spin system.

The novelty of the present work lies in providing a unified open-system analysis of quantum correlations in the hydrogen hyperfine structure, focusing on entanglement and EPR steering for a coherent initial state . Unlike previous studies, we employ alternative quantum measures, including the concurrence, the Uhlmann fidelity, and an entropic steering witness, to capture the full dynamics under dissipative evolution. Our analysis highlights the interplay between hyperfine coupling and dissipation in governing the decay of quantum correlations and identifies dynamical regimes where entanglement exhibits greater robustness than steering. These results provide new physical insights and a compact framework for understanding correlation dynamics, with potential relevance for future atomic-scale experiments and theoretical investigations.

This manuscript is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the hyperfine Hamiltonian of the hydrogen atom. In

Section 3, we present the quantum dynamics by modeling the time evolution of the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine structure via the Lindblad master equation.

Section 4 presents the quantum steering measure, concurrence, and fidelity. In

Section 5, we examine their time-dependent behavior under dissipative dynamics.

Section 6 concludes with a summary of the key results and their implications.

2. Hyperfine Interaction and Spin Structure of the Hydrogen Atom

The ground-state manifold of the hydrogen atom encapsulates rich internal structure arising from the intrinsic spin degrees of freedom of its two elementary constituents: the electron and the proton [

38,

39,

40,

41]. These particles, both spin-

fermions, interact via a magnetic dipole–dipole mechanism known as the hyperfine interaction, which originates from the coupling between their respective magnetic moments. This interaction leads to a fine energy-level splitting that is both theoretically fundamental and observationally significant in atomic physics and astrophysics.

The effective Hamiltonian describing this spin–spin coupling takes the form:

where

and

are the Pauli vector operators acting on the electron and proton spin spaces, respectively, and

A is the hyperfine structure constant. The scalar product

accounts for the isotropic exchange interaction between the two spin-1/2 particles. This Hamiltonian has the same mathematical structure as the isotropic Heisenberg exchange Hamiltonian, where the coupling constant is often denoted by

J. In the atomic-physics convention, however, we denote it by

A, the hyperfine structure constant, which quantifies the Fermi contact interaction between the electron and proton spins in hydrogen.

The hyperfine structure constant

A reflects both relativistic and quantum electrodynamic contributions and is given by [

38,

39,

40,

41]:

where

is the fine-structure constant,

and

are the electron and proton

g-factors,

is the vacuum permeability,

is the Bohr radius, and

,

are the masses of the electron and proton, respectively.

The total spin Hilbert space

is four-dimensional, with a convenient computational basis defined by the tensor products of spin eigenstates:

where ↑ and ↓ denote spin-up and spin-down states, respectively, and the subscripts

e and

p indicate the electron and proton.

Diagonalizing yields two distinct subspaces:

A singlet state (

), antisymmetric under exchange:

Three triplet states (

), symmetric under exchange:

The energy difference between the singlet and triplet manifolds is known as the hyperfine splitting,

, which corresponds to the emission or absorption of a photon with a wavelength of approximately 21 cm (frequency of 1420 MHz). This transition is of profound significance in radio astronomy, enabling the detection and mapping of neutral hydrogen in the interstellar medium. Beyond its relevance to astrophysics, the spin eigenstates exhibit essential quantum features: the singlet

and symmetric Bell-like state

are maximally entangled, while

and

are product (separable) states. This makes the hydrogen atom a prototypical platform for demonstrating foundational quantum phenomena such as entanglement, coherence, and spin correlation. From a quantum information science perspective, the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine system constitutes a natural realization of a two-qubit architecture with intrinsic entanglement and symmetry properties. Its simplicity and experimental accessibility render it an ideal model for exploring the dynamics of quantum correlations, decoherence, and control in low-dimensional systems [

41].

In conclusion, the hyperfine structure of hydrogen offers a solid basis for exploring non-classical correlations at the confluence of atomic physics and quantum information. Besides the well-known 21 cm line, higher-frequency radio transitions are crucial in astrophysics and fundamental physical tests, such as precise measurements of gravitational light bending at 15–43 GHz with the VLBA [

42]. Other two-qubit systems with singlet–triplet splittings within this range, including positronium [

43] or light diatomic molecules such as CO and OH [

44], have the potential to broaden this framework. This extension would facilitate the investigation of steering and entanglement in contexts that are directly significant for astrophysical observations and precise gravitational assessments.

3. Lindblad Dynamics of the Hydrogen Atom’s Hyperfine Spin System

To understand the time-dependent behavior of the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine structure in a realistic setting, it is essential to incorporate both coherent interactions and irreversible dissipative effects. In this section, we derive the time-evolved density matrix under the framework of open quantum systems. The dynamics are governed by the Lindblad master equation, which provides a consistent and physically motivated description of non-unitary evolution due to environmental interactions.

We consider the ground-state hyperfine manifold of the hydrogen atom, formed by the spin-

electron and proton. The four-dimensional Hilbert space of the composite system is spanned by the computational basis, which is given in Equation (

3).

To model decoherence with the hyperfine Hamiltonian Equation (

1), we introduce the standard Gorini-Kossakowski-Sudarshan-Lindblad (GKSL) equation [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]:

where

denotes the dissipator superoperator that captures environmental effects.

The dissipator is defined as:

with

representing the dissipation rate. The Lindblad operators

describe independent spin-flip processes of the electron and proton:

where

and

are the raising and lowering operators, and

,

are identity operators on the electron and proton subspaces, respectively.

Before addressing the choice of dissipator used in this work, it is useful to recall that the dominant environmental mechanism affecting the hydrogen hyperfine manifold is collisional spin exchange between atoms. Such collisions induce simultaneous flips of the electron and nuclear spins, transferring population among the hyperfine states rather than acting independently on each spin. As a result, the corresponding dissipators are intrinsically non-local in the computational basis and generally involve unequal excitation and relaxation rates. In dense gases, spin-exchange collisions may also lead to effective non-linear master equations [

52,

53].

We emphasize that the local Lindblad dissipator employed in this work is a simplified, illustrative model, chosen to provide a transparent and analytically tractable framework for exploring the qualitative behavior of quantum correlations such as entanglement and EPR steering under dissipation. While this approach does not capture the full complexity of spin-exchange interactions in a real hydrogen system, it allows us to identify general features of decoherence and correlation decay. Quantitative predictions for experimental systems would require more sophisticated treatments incorporating non-local and possibly non-linear dissipative dynamics.

On the other hand, we note that the hyperfine Hamiltonian, Equation (

1), has the same mathematical structure as an isotropic Heisenberg exchange Hamiltonian. In the context of open quantum dynamics, the interplay between the system Hamiltonian and the Lindblad operators determines whether decoherence acts trivially in the Hamiltonian eigenbasis (pure dephasing) or whether it couples populations and coherences. Specifically, if the jump operators commute with the Hamiltonian,

, one obtains the well-studied pure dephasing case. If instead

, the dynamics become nontrivial, as dissipation and coherent evolution are interconnected.

For the spin-flip operators considered here, e.g.,

and

, one finds explicitly that

. This non-commutativity implies that the dissipative channels studied here go beyond the pure dephasing scenario extensively analyzed in the literature [

54]. Moreover, while Schirmer et al. [

54] formulated their solution in the eigenbasis of the Hamiltonian, leading to a complete decoupling of populations and coherences when

, our treatment employs the computational basis

, which is not entirely composed of eigenstates of

that are given in Equations (4)–(7). Consequently, the populations and coherences are coupled, and the density matrix exhibits nontrivial off-diagonal evolution even under dissipation. This richer structure provides insight into how non-commuting Lindblad operators induce coherence–population coupling and modify the system’s dissipative dynamics.

In the present study, for the chosen initial state

Appendix A, the numerical results show purely decaying behavior without oscillations, as the coherence terms decay monotonically with time. Therefore, the current results represent a particular case of a broader class of dynamical behaviors governed by the non-commutativity of

and

, illustrating how the decay of quantum correlations depends sensitively on the chosen initial state.

Expanding the master equation in the computational basis, we obtain a system of coupled differential equations governing the matrix elements . These naturally decouple into the population (diagonal) and coherence (off-diagonal) sectors.

Due to the Hermiticity of the density matrix, the remaining matrix elements satisfy , and do not need to be computed independently.

This set of differential equations forms the foundation for analyzing the dissipative quantum dynamics of the hydrogen hyperfine structure. It enables the exploration of entanglement evolution, decoherence, and the temporal behavior of spin correlations under various initial conditions and environmental couplings.

4. Quantifying Quantum Correlations in the Hyperfine Spin System

In this section, we investigate the dynamical behavior of quantum correlations and coherence properties in the hyperfine spin system of a hydrogen atom, treated as an open quantum two-qubit system under Lindblad evolution. We explore how distinct quantifiers—each highlighting a different facet of quantum information—evolve under the influence of coherent spin–spin interactions and environmental decoherence. First, we analyze the population and coherence dynamics for an initially spin-aligned superposition state, providing insight into the interplay between unitary evolution and dissipative effects. Then, we examine quantum steering using an entropic uncertainty relation (EUR)-based steering inequality, which serves as a powerful witness of nonlocality beyond entanglement. We proceed to quantify entanglement through the concurrence, a widely used measure in two-qubit systems that captures both pure- and mixed-state correlations. Finally, we employ quantum fidelity to assess the similarity between the time-evolved state and reference states.

4.1. Decoherence and Population Dynamics of a Spin-Aligned Superposition State

In the present work, we focus on initial states lying in the triplet sector, which commutes with . Consequently, the system exhibits purely dissipative decay without coherent oscillations. This choice allows us to isolate and analyze the effect of dissipation on entanglement and steering, providing a clear understanding of the decay mechanisms in a naturally occurring atomic system.

In addition, for completeness and to guide interested readers, we note that oscillatory behavior of entanglement and related quantum correlations can arise when the initial state does not commute with

. Such cases have been investigated in detail in our previous works [

55,

56], where initial superpositions of singlet and triplet states induce coherent oscillations that modulate the time evolution of entanglement and coherence.

In this subsection, we specifically investigate the time evolution of the hyperfine spin system initialized in a coherent superposition of the fully aligned states [

41,

57,

58,

59],

The system dynamics, governed by the Lindblad master equation, leads to non-trivial evolution of the populations and coherences, particularly between the

and

components. This configuration allows us to track both decoherence and population redistribution over time. For clarity and brevity, the full analytical expressions for the time-dependent density matrix elements are provided in

Appendix A.

4.2. Entropic Steering Inequality in the Hyperfine Electron–Proton System

To investigate quantum steering in the electron–proton system, we analyze the entropic uncertainty relation (EUR) steering inequality. A quantum state is considered steerable if it violates this inequality. Building on earlier developments [

60,

61], Walborn et al. [

62] demonstrated that for continuous observables compatible with a local hidden (LH) state model, the positivity of the continuous relative entropy implies

where

is the continuous Shannon entropy associated with the conditional probability density

. Here, the continuous Shannon entropy is defined as

which quantifies the uncertainty in the measurement outcomes of the observable

conditioned on the hidden variable

.

This notion is distinct from the von Neumann entropy,

which measures the intrinsic uncertainty of the quantum state itself. Thus, while

captures the statistical uncertainty of measurement results,

characterizes the mixedness of the underlying state. Within the EUR framework, both notions play complementary roles.

In particular, Walborn et al. [

62] established that states admitting an LH state model in position and momentum space must satisfy

Here, the superscripts a and b label the electron and proton qubits, respectively. For example, () denotes the measurement outcome of observable x on the electron (proton), while () refers to the corresponding complementary observable (e.g., momentum or Pauli conjugate).

Extending this framework, we observe that the same principles constraining LH state models for continuous observables apply to discrete observables [

60]. The positivity of relative entropy holds for both continuous and discrete variables, enabling the formulation of an LH state constraint for discrete systems:

, where

denotes the discrete Shannon entropy of

. This leads to a novel entropic steering inequality for discrete variables:

Similarly, for discrete-variable systems, and (respectively, and ) denote observables measured on subsystems A and B, with eigenbases and spanning the N-dimensional Hilbert space. The complementarity factor is defined as , which quantifies the maximal overlap between the eigenvectors of and .

For two-dimensional systems, we restrict to Pauli operators, such that

(

) denote Pauli measurements on the electron (proton), the EUR steering inequality becomes [

60]:

with steering indicated by a violation of this bound. For a two-qubit

X-state in the computational basis

, one can apply suitable local unitary transformations and a Bloch decomposition to write the density matrix in terms of vectors

and

and correlation coefficients

[

60,

61,

62,

63]. In this form, the entropic uncertainty relation (EUR) steering inequality under Pauli measurements reads [

63]:

where the parameters

are extracted from the density matrix elements

as

Here, denote the diagonal elements, and , denote the anti-diagonal elements of the X-state density matrix. This explicit mapping provides a direct procedure to compute the EUR steering witness from any two-qubit X-state , allowing reproduction of the curves plotted in the figures.

Equation (

27) may appear intricate, yet each term holds a distinct information-theoretic significance, reflecting the interplay of coherences and populations in the two-qubit system. The coefficients

and

encode the inter-qubit coherences, directly influencing the conditional entropies tied to the Pauli measurements

and

. In contrast, the parameters

r and

s capture population imbalances along the

z-axis, while terms involving

govern the joint probabilities for

measurement outcomes. Collectively, the left-hand side of Equation (

27) quantifies the aggregate conditional uncertainty,

. A violation of the bound of 2 indicates that local measurements on the electron qubit can nonlocally steer—and thereby reduce the uncertainty in—the proton qubit’s outcomes in a way incompatible with any classical local hidden-state (LHS) model, thus confirming the presence of genuine quantum steering. This inequality fundamentally enforces the quantum-mechanical limit that conditional knowledge cannot arbitrarily suppress uncertainties across complementary observables, underscoring steering’s role as a directional quantum resource.

Quantum steering manifests as the capacity of one subsystem to remotely influence, via local measurements, the conditional states of another subsystem in a manner defying LHS explanations. The entropic steering inequality serves as a robust witness for this effect across both discrete- and continuous-variable regimes, bridging foundational quantum nonlocality with practical applications in asymmetric quantum tasks. In this work, the bipartite electron–proton spin system in the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine structure provides an ideal natural platform for quantifying such steering. Here, EPR steering elucidates the asymmetric directional control exerted by measurements on one spin over the other’s conditional states—a nuance not fully captured by symmetric entanglement metrics like concurrence. Although steering is often framed in terms of trusted versus untrusted parties for quantum cryptography, our application leverages it to reveal correlation asymmetries in a fundamental atomic system, particularly under dissipative Lindblad dynamics, where steering proves more fragile than entanglement. Experimentally, these steering correlations could be probed via spin-resolved techniques tailored to hyperfine states, such as optical pumping combined with spin-polarization readout or atomic-beam magnetic resonance spectroscopy, potentially enabling real-time control in noisy environments. Overall, the entropic steering inequality offers a versatile framework for dissecting the directional and asymmetric quantum correlations in the hydrogen hyperfine system, complementing our analysis of entanglement resilience and fidelity under dissipation, and highlighting pathways to engineer robust non-classical effects in atomic platforms.

4.3. Concurrence as a Measure of Entanglement

Quantifying entanglement is crucial for gaining deeper insight into the behavior of quantum systems subject to environmental decoherence. While EPR steering emphasizes the directional and asymmetric aspects of quantum correlations, concurrence provides a symmetric quantifier of the degree of entanglement shared between the electron and proton spins. By analyzing both measures, we obtain complementary perspectives on the nature and evolution of nonclassical correlations within the hydrogen hyperfine system, thereby offering a more complete characterization of its dissipative dynamics.

In the specific context of the hydrogen atom’s hyperfine structure, the temporal evolution of entanglement captures the robustness of quantum correlations under spin–spin interactions and environmental dissipation. Among the various entanglement measures, the concurrence introduced by Wootters [

59] stands out as a particularly useful and analytically tractable tool for two-qubit systems. It provides a direct connection to the concept of entanglement of formation and allows for a transparent quantification of how the shared quantum coherence between the electron and proton spins degrades over time.

For a general two-qubit system described by a density matrix

, the concurrence

is defined as [

59,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]:

where

(for

) are the eigenvalues, arranged in decreasing order, of the matrix

. The matrix

represents the spin-flipped counterpart of

, defined by:

where

is the complex conjugate of

, and

is the Pauli

y-matrix, widely used to represent spin and polarization states in quantum mechanics.

Concurrence satisfies , where indicates a separable state, corresponds to a maximally entangled Bell state, and intermediate values describe partially entangled states.

In our case, the density matrix that changed in time

, derived under the Lindblad formalism, exhibits a block structure in which coherence is confined to the subspace

, as described in

Appendix A. This structure simplifies the concurrence calculation by focusing on a reduced effective subspace.

Substituting the relevant matrix elements into the definition, the analytical expression for concurrence reveals the interplay between coherent evolution and dissipative decay in the hyperfine spin system of the hydrogen atom. Specifically, the concurrence evolves as

which captures the dependence of quantum entanglement on the decoherence rate

, the evolution time

t, and the initial state parameter

. The first term represents the decaying coherence between the spin components, while the second term accounts for the loss of purity due to population redistribution. As these two competing effects evolve, the concurrence may vanish entirely at a finite time, a phenomenon known as entanglement sudden death (ESD). The critical time

at which

yields the disentanglement threshold:

This result highlights that the lifetime of entanglement is strongly dependent on the initial degree of coherence encoded in , as well as the environmental noise strength . Maximal initial entanglement () leads to prolonged persistence of quantum correlations, whereas weakly entangled or nearly separable states are rapidly degraded by dissipation. These expressions provide an exact and transparent characterization of how entanglement evolves and eventually vanishes in a realistic open quantum system.

4.4. Fidelity as a Measure of Quantum State Similarity

Fidelity is a central metric in quantum information theory to quantify the proximity between two quantum states [

72,

73,

74,

75]. For arbitrary mixed states

and

, the fidelity is defined via the Uhlmann formula:

This expression satisfies , with if and only if , and when the states are orthogonal and fully distinguishable.

In the particular case where both states are pure, i.e.,

and

, the fidelity reduces to the squared inner product between the two states:

For completeness, the full derivation of this fidelity expression as applied to the hydrogen hyperfine system, together with its explicit evaluation using the time-dependent density matrix

, is provided in

Appendix B.

Fidelity plays a critical role in evaluating the performance of quantum operations, including gate implementation, quantum channel transmission, and quantum error correction protocols. It also serves as a reference point in quantum state tomography, where the reconstructed density matrix is compared against an ideal or target state [

35,

76]. A high fidelity value indicates a strong resemblance between states, making it an essential diagnostic tool in both theoretical modeling and experimental validation. In the context of the present study, fidelity will be used to assess the temporal evolution of the quantum state

under Lindblad dynamics, comparing it to a desired reference state

. This comparison provides complementary insight to entanglement quantifiers by revealing how closely the system remains to an idealized or maximally entangled configuration as decoherence progresses. In summary, this section has outlined the theoretical framework for characterizing quantum correlations in the hydrogen hyperfine spin system. We have introduced complementary indicators of nonclassical behavior: population dynamics under decoherence, the entropic steering inequality, concurrence as a quantitative measure of entanglement, and fidelity as a benchmark of quantum state similarity. Together, these tools provide a coherent basis for assessing the resilience and evolution of quantum correlations in the presence of environmental noise. In the following section, we employ these measures in explicit numerical simulations to track the time-dependent behavior of steering, entanglement, and fidelity for representative initial states of the electron–proton system.

5. Analysis of Quantum Dynamics and Correlation Measures

We now turn to a numerical analysis of the dissipative dynamics of the hydrogen hyperfine system. Building on the theoretical framework developed in the previous sections, we evaluate how decoherence impacts population evolution, quantum steering, entanglement, and fidelity across different initial states and dissipation rates. The numerical simulations provide concrete insight into the temporal behavior of these correlation measures, allowing us to identify characteristic features such as robustness hierarchies, sudden death phenomena, and asymptotic convergence. This quantitative analysis forms the basis for the discussion of our main results. Throughout the manuscript, the time variable on the x-axis is expressed in dimensionless units as , where A is the hyperfine coupling constant. This choice renders the dynamics dimensionless and allows for a direct comparison across different dissipation rates.

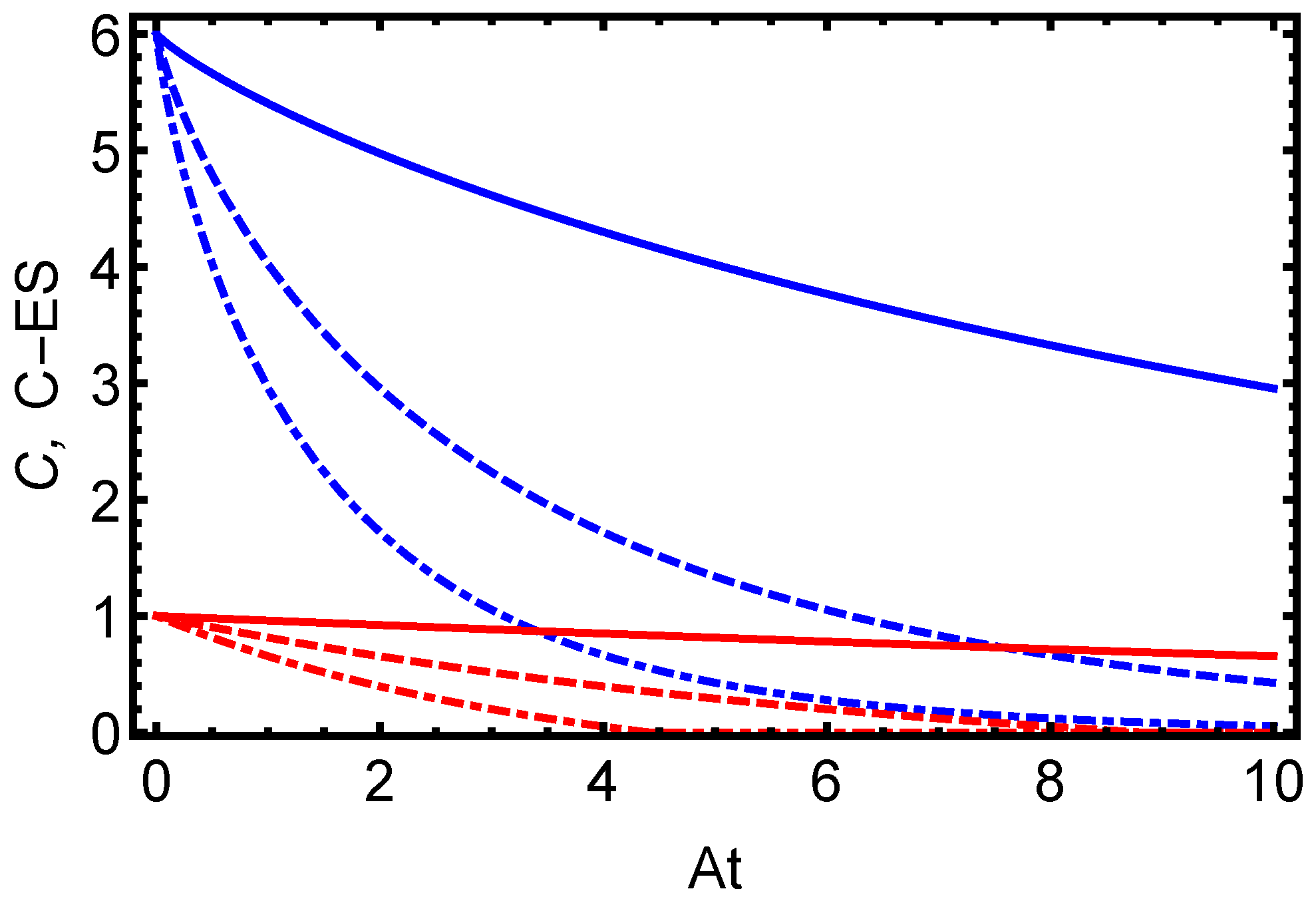

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal dynamics of key quantum correlation measures; specifically, quantum steering (depicted in blue curves) and entanglement (quantified via concurrence and shown in red curves), in the electron–proton hyperfine spin system of the hydrogen atom. The system is initially prepared in the maximally entangled Bell state

which capitalizes on the magnetic dipole–dipole coupling between the spins to achieve maximal initial correlations, setting the stage for studying the competition between the coherent hyperfine evolution and environmental dissipation as described by the Lindblad master equation. The plots capture the evolution of these measures over time (in units of

) for dissipation rates

(solid lines),

(dashed lines), and

(dash-dotted lines), with

parameterizing the rate of spin-flip processes (via Lindblad operators for electron and proton relaxation/excitation) that drive decoherence and disrupt the density matrix elements. For the smallest

, the measures decay slowly, as the hyperfine Hamiltonian—with its energy splitting

eV—overwhelms dissipative effects, maintaining coherences like

and supporting prolonged quantum correlations through spin precession dynamics. As

increases to 0.05A and 0.1A, the decay intensifies, with stronger environmental interactions that accelerate the loss of correlations and drive the system toward an incoherent mixture, reflecting a Markovian approximation where irreversible processes dominate and exponentially suppress non-classical features on shorter timescales. A key insight is the greater resilience of entanglement compared to quantum steering across all

, where steering vanishes while entanglement lingers, notably at lower dissipation rates. This manifests in the figure as blue curves (steering measure) crossing the critical threshold first, entering the non-steerable region, while red curves (concurrence) stay above zero, indicating ongoing entanglement post-steering loss. Steering is gauged by the entropic uncertainty relation measure from Equation (

24), the sum of conditional Shannon entropies

under Pauli measurements on electron (A) and proton (B); steering exists for sums

(violating the ≥2 bound for states with local hidden state models) and disappears for ≥2. The faster demise of steering arises from its asymmetric, task-oriented nature—requiring one party’s measurements to steer the other’s state beyond classical limits—which proves more susceptible to dissipation-induced asymmetry in the X-state density matrix, where coherences decay as

and marginal entropies increase unevenly. Entanglement, assessed symmetrically via concurrence, endures in separable-incompatible mixed states even after steerability fades, embodying the correlation hierarchy where entangled states encompass but exceed steerable ones.

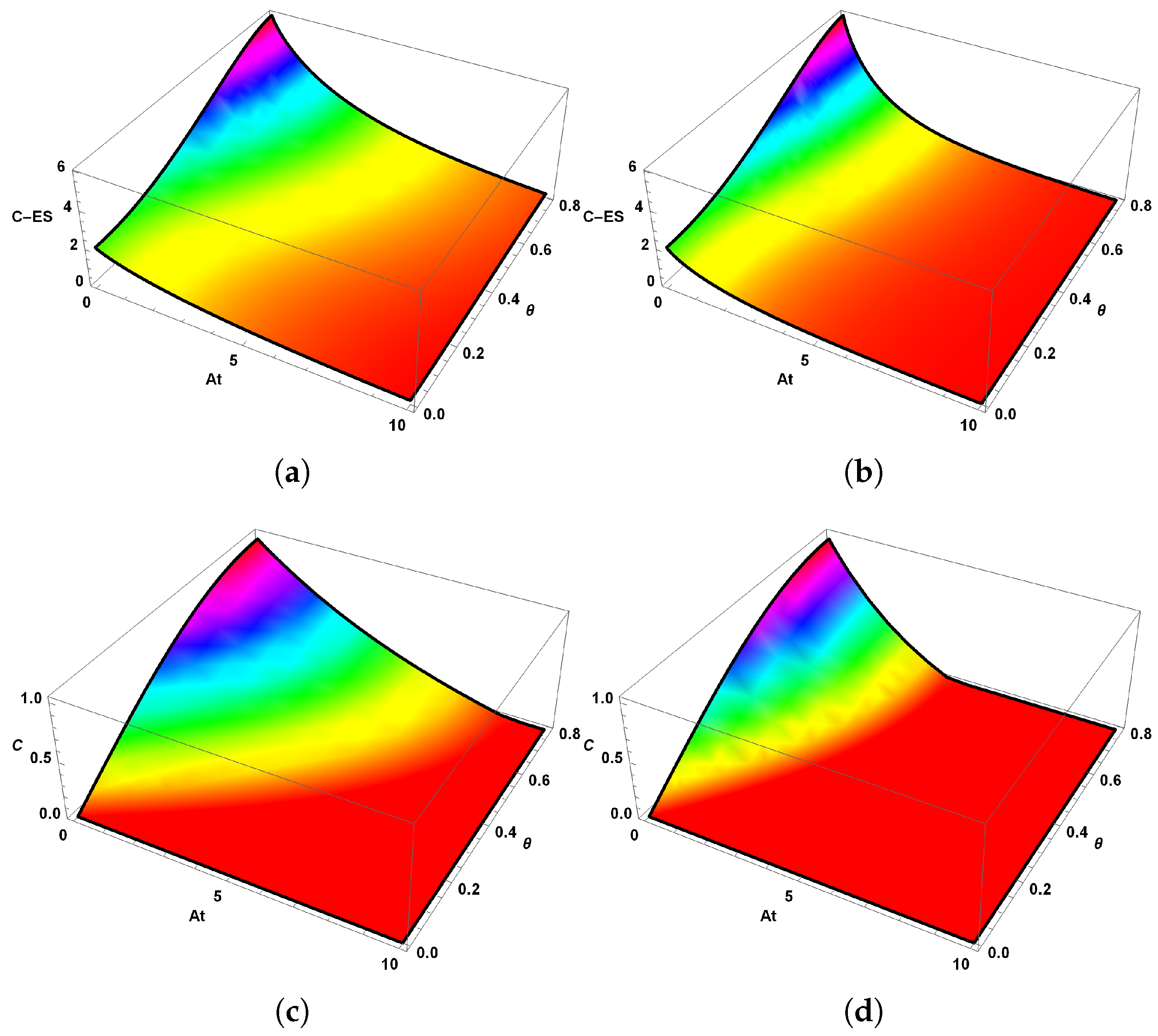

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive visualization of the quantum correlation measures—quantum steering in

Figure 2a,b and entanglement (through concurrence) in

Figure 2c,d—as functions of time

t and the initial state parameter

, for the electron–proton hyperfine spin system in the hydrogen atom under dissipative dynamics. The system starts in the pure state

, which generalizes the Bell state at

to a family of superpositions tunable by

, allowing exploration of how initial correlations influenced during the time evolution under the Lindblad master equation driven by the hyperfine Hamiltonian and environmental spin-flip dissipation. The

Figure 2a,c correspond to a dissipation rate

, while

Figure 2b,d use

. In

Figure 2a,b, the steering measure evolves across the

t-

plane: steering is present below the threshold of 2 (violation region) and absent at or above 2. For

Figure 2a, steering persists longest near

, where initial correlations are maximal, gradually decaying over time due to preserved correlations in the X-state density matrix; as

deviates toward 0 or

(separable limits), steering vanishes quickly, reflecting weaker initial non-classicality. At higher

Figure 2b, the steerable region shrinks markedly, with faster crossings to non-steerable values across all

, as intensified dissipation erodes the directional influence needed for one subsystem (e.g., electron) to remotely steer the other (proton) beyond local hidden state models.

Figure 2c,d show concurrence, which quantifies entanglement and ranges from 0 (separable) to 1 (maximally entangled), exhibiting similar but more resilient patterns: peaks near

decay slower than steering, persisting in broader

t-

regions even after steering thresholds are crossed. For

Figure 2c, entanglement survives longer across a wider

range, while for

Figure 2d, the decay accelerates but still outlasts steering, highlighting the symmetric nature of the entanglement that withstands mixing better than the task-specific asymmetry of steering. This comparison reveals the correlation hierarchy, steerable states are a subset of entangled ones, with dissipation pushing the system into entangled-yet-non-steerable regimes, especially for intermediate

.

Interestingly, as time progresses, the

-dependence of both the entanglement and steering measures becomes progressively smoothed, leading to nearly

-independent values in the long-time limit. This smoothing is partially due to the occurrence of sudden death of entanglement for certain initial-state angles

, which effectively flattens the correlation landscape. As confirmed by the asymptotic forms of the density-matrix elements in Equations (A7), (A9) and (A10), long-term solutions indeed lose any explicit dependence on the initial parameter

. While we do not formally map this behavior to a geometric Ricci flow [

77], the analogy provides a useful conceptual perspective: the dissipative Lindblad evolution drives the system toward a more uniform distribution of correlations, highlighting a form of universal behavior in the asymptotic state.

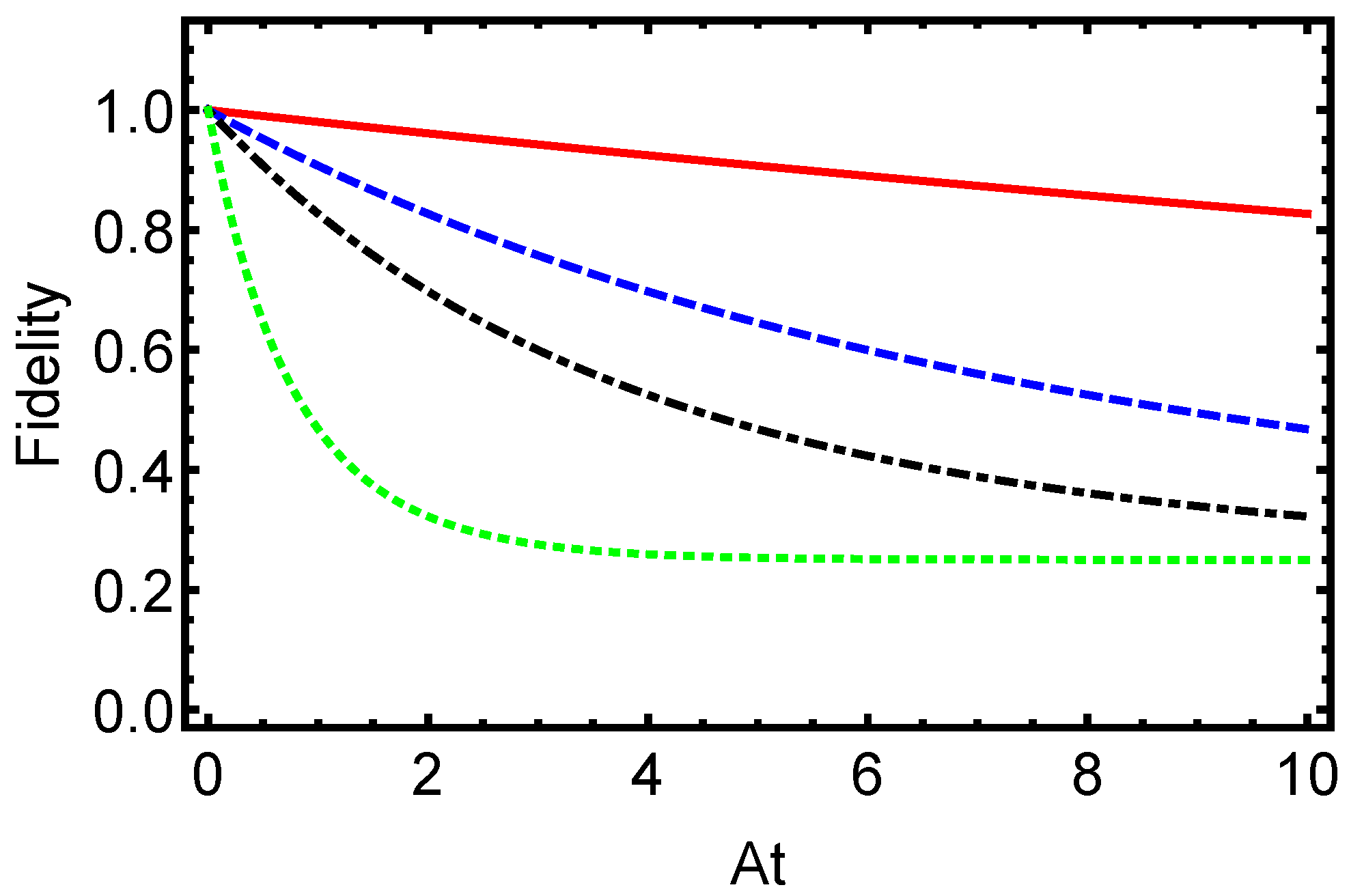

Figure 3 depicts the temporal evolution of quantum fidelity in the electron–proton hyperfine spin system of the hydrogen atom’s ground state, initially prepared in the maximally entangled Bell state

, equivalent to

. Fidelity quantifies the similarity between the time-evolved density matrix

under Lindblad dissipative dynamics and the pure initial state

, ranging from 1 (identical states) to 0 (orthogonal states). The plots show fidelity as a function of time for dissipation rates

(solid line),

(dashed line),

(dash-dotted line), and

(dotted line), where

governs the strength of environmental spin-flip processes (via electron and proton relaxation/excitation operators) that compete with the coherent hyperfine evolution. For the lowest

(solid line), fidelity decays slowly from its initial value of 1, preserving coherences like

and maintaining state similarity over longer timescales through spin precession. Physically, this weak-coupling regime minimizes decoherence. As

increases to 0.05A (dashed) and 0.1A (dash-dotted), the decay accelerates progressively, reflecting heightened environmental interactions via irreversible processes in the Markovian Lindblad framework. At the highest

(dotted line), fidelity plummets rapidly, indicating strong dissipation. This

-dependent behavior underscores fidelity’s role as a diagnostic for decoherence in open quantum hydrogen atoms, where higher noise shortens the coherence timescale, limiting quantum state preservation.

In summary, while the qualitative features of the dissipative dynamics reported here—namely, the greater robustness of entanglement compared to steering and the monotonic decrease of fidelity with increasing noise—are consistent with generic two-qubit models, their realization within the hydrogen hyperfine structure is noteworthy. This system represents a fundamental atomic two-qubit, naturally arising from the coupled electron–proton spins and of central importance in both atomic physics and astrophysics. Unlike abstract toy models, the hyperfine platform is experimentally accessible through atomic-beam spectroscopy, optical pumping, and spin-resolved detection, with the 21 cm transition also serving as a cornerstone of radio astronomy.

Our study extends correlation and steering analyses to this concrete physical setting, demonstrating that electron–proton steering can be monitored and manipulated via experimentally controllable parameters. In doing so, we provide a bridge between foundational quantum information concepts and a universally relevant atomic system, highlighting its potential for steering-based protocols and experimental quantum information processing in atomic platforms. While our study does not implement active control protocols, the dynamics of steering and entanglement can be influenced by experimentally accessible parameters. Specifically, the initial state preparation (e.g., the choice of superposition angle

) and the strength of local dephasing rates

provide a way to manipulate the temporal evolution of correlations, delay the sudden death of entanglement, and extend the persistence of steering measure. In this sense, the system allows for a form of control over correlation dynamics, consistent with the aims outlined in the abstract. It is worth noting related recent work on the influence of structured magnetic fields and open-system dynamics [

78]. In that study, the authors investigate how exponential and periodic magnetic pulses affect the formation of quantum correlations and non-Markovianity in diverse field landscapes. While their focus is on engineered magnetic-field configurations and non-locally correlated channels, our present work instead examines the intrinsic hyperfine structure of the hydrogen atom under dissipative Lindblad dynamics. Despite these differences, both studies highlight the sensitivity of entanglement and related quantum correlations to the interplay between system Hamiltonians and environmental interactions, underscoring the broader relevance of controlling quantum correlations in open systems.

On the other hand, the hyperfine structure of hydrogen atoms can be probed and manipulated using well-established experimental techniques such as optical pumping and atomic-beam magnetic resonance. Typical values for the hyperfine coupling are ∼ GHz, while the decay rates due to environmental interactions are on the order of ∼–, depending on the system and experimental conditions. Feasible magnetic field strengths used to control or tune the spin states range from a few millitesla to several tesla. These values suggest that the dissipative dynamics and quantum correlations investigated in our study can be realistically accessed in current experimental setups, providing a concrete route for the detection and control of entanglement and EPR steering in hydrogen atoms.