Modelling the Shadow Economy: An Econometric Study of Technology Development and Institutional Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Preparation

2.2. Model Selection and Estimation

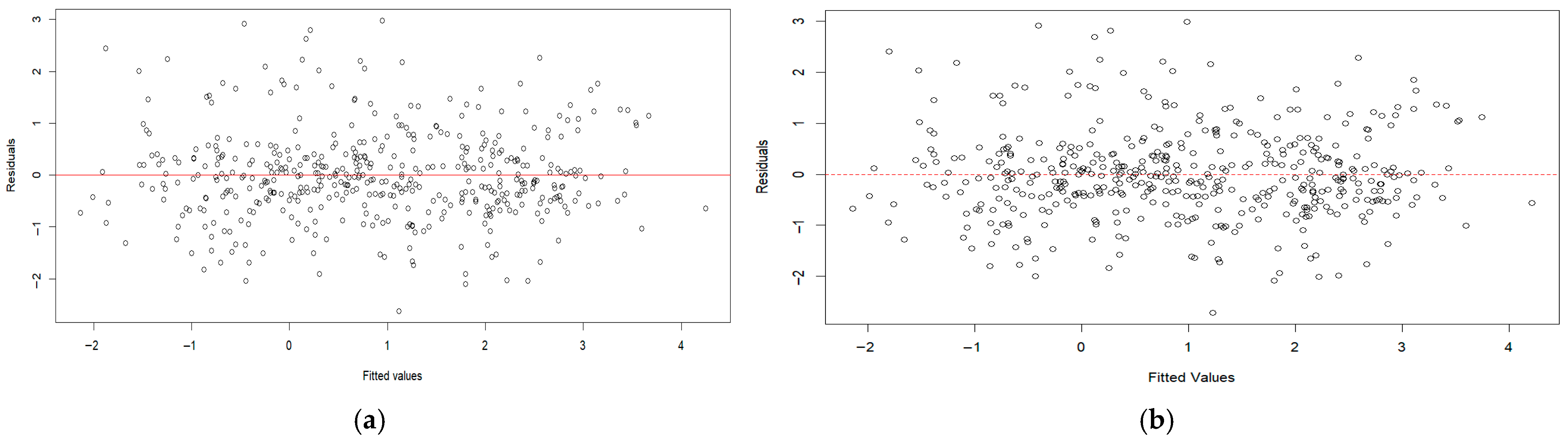

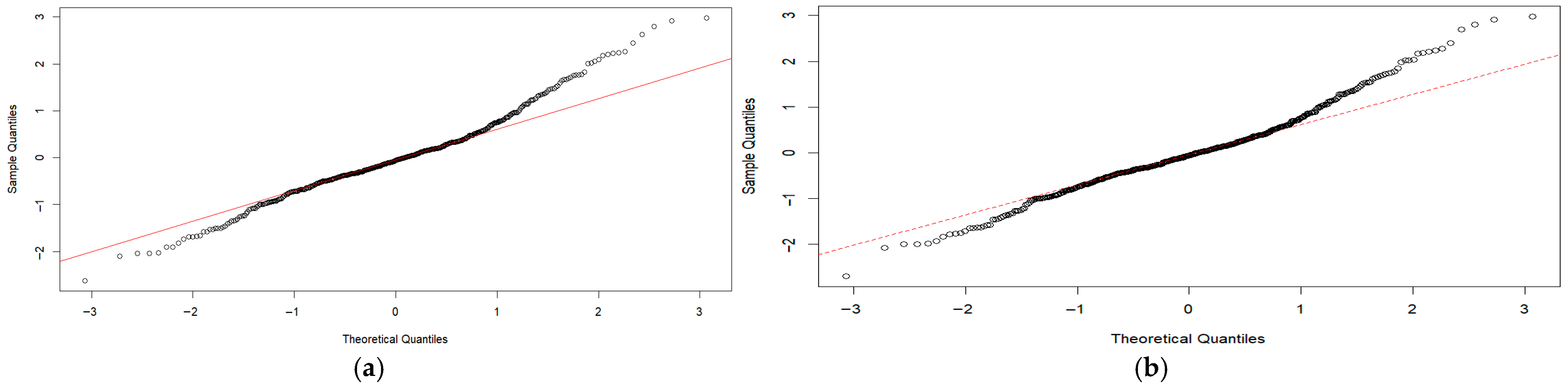

2.3. Diagnostic Testing and Robustness Checks

2.4. Addressing Multicollinearity

2.5. Refining the Model with Time Effects

2.6. Dynamic Panel (GMM) Model Exploration

3. Results

4. Discussion

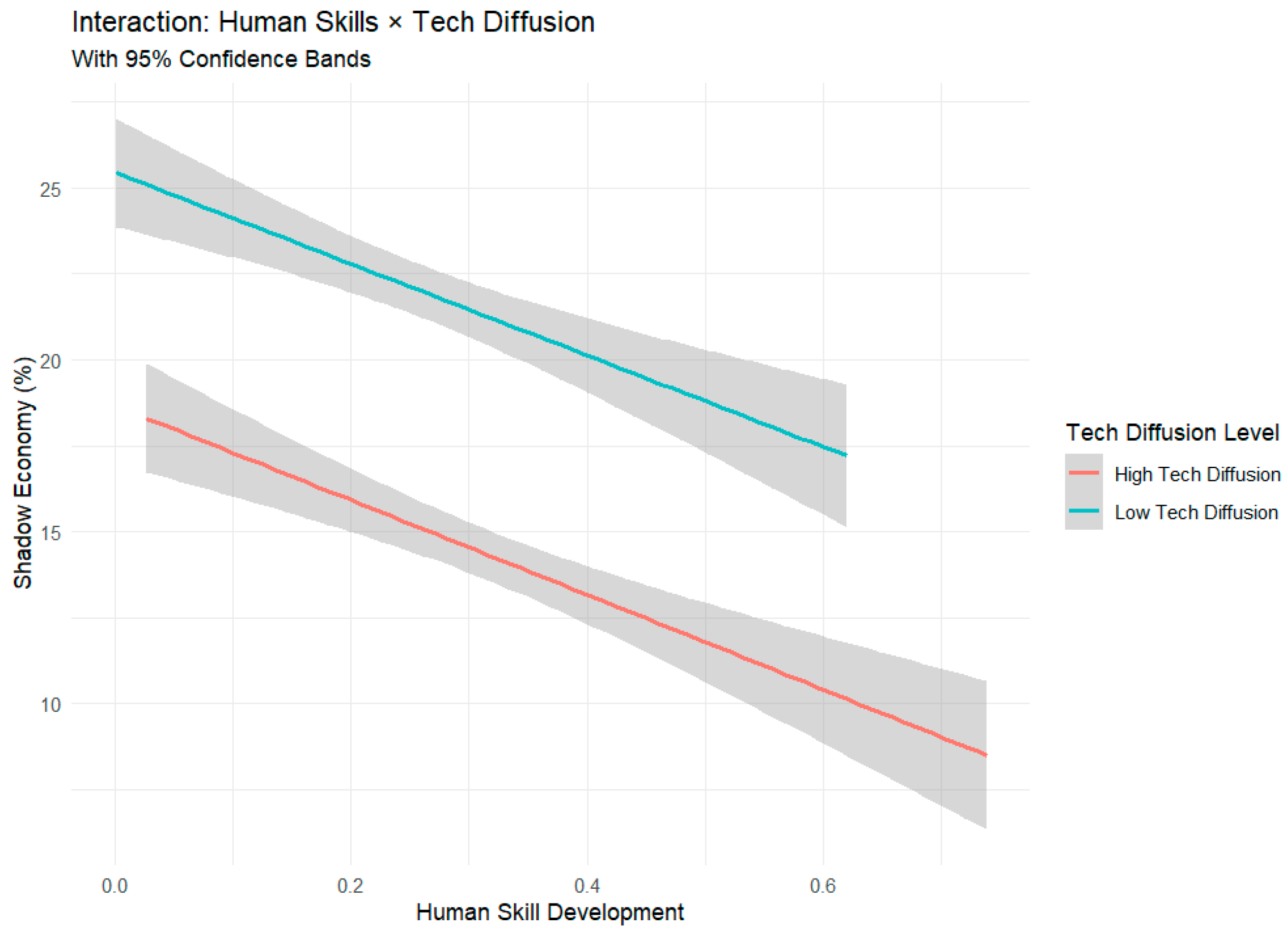

4.1. Structural Drivers: Hierarchy and Conditional Effects

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TAI | Technological Achievement Index |

| CNT | Creating New Technologies (TAI dimension) |

| DNT | Diffusion of New Technologies (TAI dimension) |

| DOT | Diffusion of Old Technologies (TAI dimension) |

| DHS | Development of Human Skills (TAI dimension) |

| CC | Control of Corruption (WGI indicator) |

| GE | Government Effectiveness (WGI indicator) |

| RL | Rule of Law (WGI indicator) |

| RQ | Regulatory Quality (WGI indicator) |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| FE | Fixed Effects (model) |

| RE | Random Effects (model) |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| WGI | Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| R-squared (coefficient of determination) | |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. RStudio Code Snippet A1

Appendix A.2. RStudio Code Snippet A2

Appendix A.3. RStudio Code Snippet A3

Appendix A.4. RStudio Code Snippet A4

Appendix B

| Variable | OLS Estimate (p-Value) | FE Estimate (p-Value) | RE Estimate (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 28.366 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) | N/A | 26.631 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) |

| Control.of.Corruption | 0.058 (0.949) | −1.168 (0.0098 **) | −1.494 (0.0008 ***) |

| Government.Effectiveness | −3.001 (0.0091 **) | −0.271 (0.561) | −0.508 (0.280) |

| Rule.of.Law | −5.913 (1.465 × 10−5 ***) | 1.116 (0.0627) | 0.759 (0.208) |

| Regulatory.Quality | 0.696 (0.526) | −1.649 (0.0007 ***) | −1.584 (0.0013 **) |

| New.Technology.Creation | −13.288 (9.617 × 10−8 ***) | −2.791 (0.0324 *) | −3.373 (0.0093 **) |

| New.Technology.Difusion | −2.175 (0.271) | −8.658 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) | −8.569 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 4.278 (0.0652) | 5.516 (0.0001 ***) | 4.763 (0.0006 ***) |

| Development.of.human.skills | −3.390 (0.0443 *) | −11.832 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) | −12.734 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) |

| 0.687 | 0.509 | 0.505 |

| Test Name | Statistic Value | Degrees of Freedom | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hausman Test | Chisq = 14.471 | 8 | 0.07029 | Fail to reject. RE preferred |

| Wooldridge (Serial Corr.) | Chisq = 259.36 | 16 | <2.2 × 10−16 | Significant Serial Correlation |

| Breusch-Pagan (Heteroskedasticity) | BP = 107.5 | 8 | <2.2 × 10−16 | Significant Heteroskedasticity |

| Pesaran CD (Cross-section Dependence) | Z = 28.042 | N/A | <2.2 × 10−16 | Significant Cross-sectional Dependence |

| Variable | FE (Clustered Ses) Estimate (p-Value) | RE (Driscoll-Kraay Ses) Estimate (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | N/A | 26.631 (5.012 × 10−10 ***) |

| Control.of.Corruption | −1.168 (0.2695) | −1.494 (0.0422 *) |

| Government.Effectiveness | −0.271 (0.6765) | −0.508 (0.1470) |

| Rule.of.Law | 1.116 (0.2379) | 0.759 (0.0739) |

| Regulatory.Quality | −1.649 (0.0181 *) | −1.584 (0.0539) |

| New.Technology.Creation | −2.791 (0.0182 *) | −3.373 (0.0005 ***) |

| New.Technology.Difusion | −8.658 (2.286 × 10−6 ***) | −8.569 (0.0001154 ***) |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 5.516 (0.1444) | 4.763 (0.0407 *) |

| Development.of.human.skills | −11.832 (1.712 × 10−7 ***) | −12.734 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) |

| Predictor | Initial VIF | Refined Model Estimate (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | N/A | 25.275 (9.589 × 10−8 ***) |

| Control.of.Corruption | 6.08 | −1.890 (0.0031 **) |

| Regulatory.Quality | 5.96 | Dropped |

| New.Technology.Creation | 2.88 | −3.884 (5.320 × 10−6 ***) |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 1.77 | −8.017 (0.0006 ***) |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 2.59 | 4.668 (0.0354 *) |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.78 | −12.613 (<2.2 × 10−16 ***) |

| Variable | Coefficients | Estimate Std. Error | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lag(Shadow.Economy, 1) | 0.966198 | 0.011272 | 85.7134 | <2.2 × 10−16 *** |

| Control.of.Corruption | −0.328141 | 0.101617 | −3.2292 | 0.001241 ** |

| New.Technology.Creation | −0.774208 | 0.649954 | −1.1912 | 0.233585 |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 0.977014 | 0.407590 | 2.3970 | 0.016528 * |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 0.927062 | 0.638730 | 1.4514 | 0.146665 |

| Development.of.human.skills | −0.061306 | 0.292060 | −0.2099 | 0.833738 |

| Sargan test: Chisq (45) = 27.46437 (p-value = 0.98175) | ||||

| Autocorrelation test (1): Normal = −3.82649 (p-value = 0.00012998) | ||||

| Autocorrelation test (2): Normal = 2.014791 (p-value = 0.043927) | ||||

| Shadow Economy | New Tech Diffusion | Regulatory Quality | Gov. Effectiveness | Control of Corruption | Rule of Law | Human Skills | New Tech Creation | Old Tech Diffusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

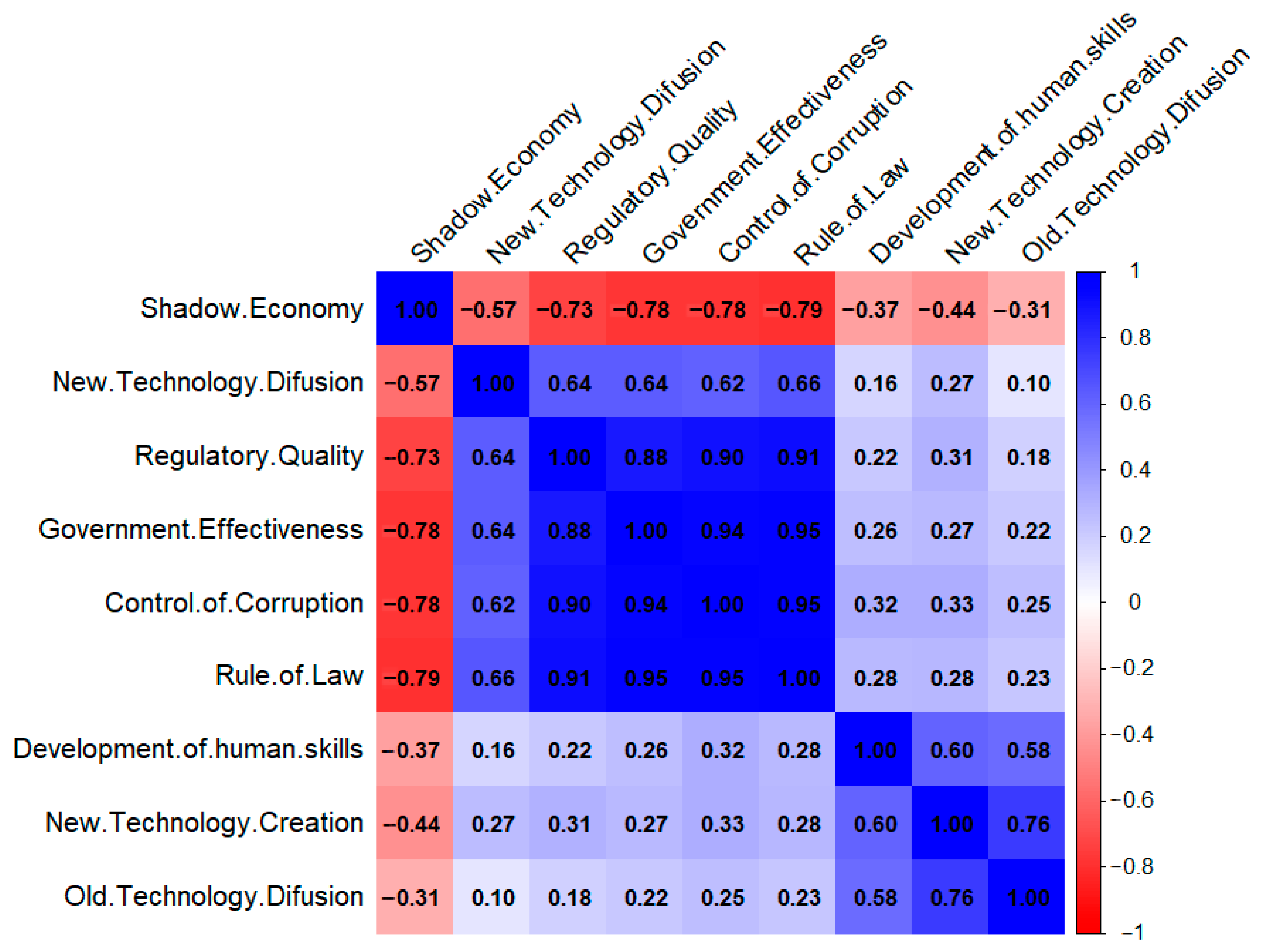

| Shadow Economy | 1.0 (p = 0) | −0.57 (p = 0.0) | −0.73 (p = 0.0) | −0.78 (p = 0) | −0.78 (p = 0) | −0.79 (p = 0) | −0.37 (p = 0.0) | −0.44 (p = 0) | −0.31 (p = 0.0) |

| New Tech Diffusion | −0.57 (p = 0) | 1.0 (p = 0.0) | 0.64 (p = 0.0) | 0.64 (p = 0) | 0.62 (p = 0) | 0.66 (p = 0) | 0.16 (p = 0.0004) | 0.27 (p = 0) | 0.1 (p = 0.0303) |

| Regulatory Quality | −0.73 (p = 0) | 0.64 (p = 0.0) | 1.0 (p = 0.0) | 0.88 (p = 0) | 0.9 (p = 0) | 0.91 (p = 0) | 0.22 (p = 0.0) | 0.31 (p = 0) | 0.18 (p = 0.0001) |

| Gov. Effectiveness | −0.78 (p = 0) | 0.64 (p = 0.0) | 0.88 (p = 0.0) | 1.0 (p = 0) | 0.94 (p = 0) | 0.95 (p = 0) | 0.26 (p = 0.0) | 0.27 (p = 0) | 0.22 (p = 0.0) |

| Control of Corruption | −0.78 (p = 0) | 0.62 (p = 0.0) | 0.9 (p = 0.0) | 0.94 (p = 0) | 1.0 (p = 0) | 0.95 (p = 0) | 0.32 (p = 0.0) | 0.33 (p = 0) | 0.25 (p = 0.0) |

| Rule of Law | −0.79 (p = 0) | 0.66 (p = 0.0) | 0.91 (p = 0.0) | 0.95 (p = 0) | 0.95 (p = 0) | 1.0 (p = 0) | 0.28 (p = 0.0) | 0.28 (p = 0) | 0.23 (p = 0.0) |

| Human Skills | −0.37 (p = 0) | 0.16 (p = 0.0008) | 0.22 (p = 0.0) | 0.26 (p = 0) | 0.32 (p = 0) | 0.28 (p = 0) | 1.0 (p = 0.0) | 0.6 (p = 0) | 0.58 (p = 0.0) |

| New Tech Creation | −0.44 (p = 0) | 0.27 (p = 0.0) | 0.31 (p = 0.0) | 0.27 (p = 0) | 0.33 (p = 0) | 0.28 (p = 0) | 0.6 (p = 0.0) | 1.0 (p = 0) | 0.76 (p = 0.0) |

| Old Tech Diffusion | −0.31 (p = 0) | 0.1 (p = 0.0303) | 0.18 (p = 0.0002) | 0.22 (p = 0) | 0.25 (p = 0) | 0.23 (p = 0) | 0.58 (p = 0.0) | 0.76 (p = 0) | 1.0 (p = 0.0) |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 24.96627 | 1.29732 | 19.2445 | <2.2 × 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.885338 | −2.74345 | 0.540722 | −5.0737 | 6.07 × 10−7 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 3.011254 | −0.86907 | 0.399326 | −2.1763 | 0.0301 | * |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 1.807557 | −3.1239 | 1.466052 | −2.1308 | 0.0337 | * |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 2.702253 | 0.446423 | 1.433022 | 0.3115 | 0.7556 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.750472 | −7.5534 | 1.950519 | −3.8725 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 0.606211 |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 25.18934 | 0.765521 | 32.9048 | <2.2 × 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.868306 | −2.77338 | 0.51539 | −5.3811 | 1.28 × 10−7 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 1.694898 | −0.85395 | 0.352749 | −2.4208 | 0.0159 | * |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 1.753471 | −3.06245 | 1.599906 | −1.9141 | 0.0563 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.69227 | −7.59814 | 1.956133 | −3.8843 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 0.607277 |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 24.26651 | 0.837472 | 28.9759 | <2.2 × 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.155256 | −2.98236 | 0.530662 | −5.6201 | 3.65 × 10−8 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 1.641864 | −0.20966 | 0.629233 | −0.3332 | 0.7392 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.635052 | −7.16996 | 2.053161 | −3.4922 | 0.0005 | *** |

| 0.598765 |

References

- Dell’Anno, R. Theories and definitions of the informal economy: A survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2022, 36, 1610–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feige, E.L. Reflections on the Meaning and Measurement of Unobserved Economies: What Do We Really Know About the ‘Shadow Economy’? J. Tax Adm. 2016, 2, 1. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2728060 (accessed on 30 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Medina, L.; Schneider, F.G. Shedding Light on the Shadow Economy: A Global Database and the Interaction with the Official One; CESifo Working Paper No. 7981; CESifo Group: Munich, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/cesifo1_wp7981.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Koufopoulou, P.; Williams, C.C.; Vozikis, A.; Souliotis, K. Shadow Economy: Definitions, terms & theoretical considerations. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2019, 9, 35–57. Available online: https://www.scienpress.com/Upload/AMAE%2FVol%209_5_3.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Schneider, F. Development of the Shadow Economy of 36 OECD Countries over 2003–2021: Due to the Corona Pandemic a Strong Increase in 2020 and a Modest Decline in 2021. Afr. J. Political Sci. 2021, 15, 1–7. Available online: https://www.fm.gov.lv/lv/media/11125/download?attachment (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Achim, M.V.; Văidean, V.L.; Borlea, S.N.; Florescu, D.R. The impact of the development of society on economic and financial crimes. Case studies for European Union member states. Risks 2021, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlán, I.; Němec, D.; Kotlánová, E.; Skalka, P.; Macek, R.; Machová, Z. European Green Deal: Environmental taxation and its sustainability in conditions of high levels of corruption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastac, L.; Vancea, D.P.C. Shadow Economy and Bibliometric Analysis: What Is the Trend in Current Times? Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2024, XXIV, 247–255. Available online: https://stec.univ-ovidius.ro/html/anale/RO/2024i2/Section%203/17.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.; Ileanu, B.V.; Florea, I.O.; Aivaz, K.A. Corruption perceptions in the Schengen Zone and their relation to education, economic performance, and governance. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.Z.; Khan, S.; Ali, M.; Rehman, F.U.; Alonazi, W.B.; Aljuaid, M. Advance Dynamic Panel Second-Generation Two-Step System Generalized Method of Movement Modeling: Applications in Economic Stability-Shadow Economy Nexus with a Special Case of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Mathematics 2023, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivaz, K.A.; Florea, I.O.; Munteanu, I. Economic Fraud and Associated Risks: An Integrated Bibliometric Analysis Approach. Risks 2024, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A.; Schneider, F. Corruption and the shadow economy: An empirical analysis. Public Choice 2010, 144, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehn, A.; Schneider, F. Corruption and the shadow economy: Like oil and vinegar, like water and fire? Int. Tax Public Financ. 2012, 19, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaku, S. Does corruption contribute to the rise of the shadow economy? Empirical evidence from Uganda. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1932246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancea, D.P.C.; Aivaz, K.A.; Duhnea, C. Political uncertainty and volatility on the financial markets—The case of Romania. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2017, 16, 457. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349105249_POLITICAL_UNCERTAINTY_AND_VOLATILITY_ON_THE_FINANCIAL_MARKETS-THE_CASE_OF_ROMANIA (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Desai, M.; Fukuda-Parr, S.; Johansson, C.; Sagasti, F. Measuring the Technology Achievement of Nations and the Capacity to Participate in the Network Age; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2002; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/ipdesai-2.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Márquez-Ramos, L.; Martínez-Zarzoso, I. The Effect of Technological Innovation on International Trade: A Nonlinear Approach. Economics 2010, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Ali, T.M.; Shahdin, S.; Rahman, T.U. Technology achievement index 2009: Ranking and comparative study of nations. Scientometrics 2011, 87, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burinskiene, A. International Trade, Innovations and Technological Achievement in Countries. In DAAAM International Scientific Book; DAAAM International: Vienna, Austria, 2013; pp. 795–812. Available online: https://www.daaam.info/Downloads/Pdfs/science_books_pdfs/2013/Sc_Book_2013-048.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Shahab, M. Technology Achievement Index 2015: Mapping the Global Patterns of Technological Capacity in the Network Age; Elsevier Editorial System for Technology Forecasting & Social Change: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 2–35. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/23906892/Technology_Achievement_Index_2015 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- İncekara, A.; Guz, T.; Sengun, G. Measuring the technology achievement index: Comparison and ranking of countries. Pressacademia 2017, 4, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağan, B. Technological Achievement of the World: An Update and Analysis of Countries, Continents and Periods. İzmir İktisat Derg. 2022, 37, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağan, B. The Impact of Technological Achievement on Economic Growth: Evidence from a Panel ARDL Approach. J. Yaşar Univ. 2022, 17, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastac, L.; Vancea, D.P.C. Technologization and economic transformation: The influence of technology adoption in reducing the shadow economy and increasing welfare. Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Fascicle I. Econ. Appl. Inform. 2025, 31, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivaz, K.A.; Tofan, I. The Synergy Between Digitalization and the Level of Research and Business Development Allocations at EU Level. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2022, 17, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivaz, K.A.; Teodorescu, D. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on medical education: A case study at a public university in Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.A.; Ahmed, F.; Kamal, M.A.; Trinidad Segovia, J.E. Assessing the Role of Digital Finance on Shadow Economy and Financial Instability: An Empirical Analysis of Selected South Asian Countries. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacaltana Janampa, J.; de Mattos, F.; García, J. New Technologies, E-Government and Informality; ILO Working Paper 112; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, F.M.; Dada, J.T. The Impact of ICT on Shadow Economy in West Africa. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 72, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Doan, C.P.; Nguyen, B.Q. How e-Government Affects the Shadow Economy: A Further Analysis. Int. Econ. J. 2025, 39, 274–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparenienė, L.; Remeikienė, R.; Navickas, V. The concept of digital shadow economy: Consumer’s attitude. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S. Worldwide governance indicators: Cross-country data set 2012–2022. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, I.; Ahmad, M.; Ismailov, D.; Balbaab, M.E.; Akhmedov, A.; Khasanov, S.; Ul Haq, M. Enhancing institutional quality to boost economic development in developing nations: New insights from CS-ARDL approach. Res. Glob. 2023, 7, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniatowicz, M.; Dziemianowicz, R.; Kargol-Wasiluk, A. Good Governance and Institutional Quality of Public Sector: Theoretical and Empirical Implications. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, XXIII, 529–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; de Dios, E.; Lagman-Martin, A. Governance and Institutional Quality and the Links with Economic Growth and Income Inequality: With Special Reference to Developing Asia; ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 193; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2010; Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28404/economics-wp193.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Institutional Quality, Governance and Progress towards the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, D.; Aivaz, K.A.; Vancea, D.P.C.; Condrea, E.; Dragan, C.; Olteanu, A.C. Consumer trust in AI algorithms used in e-commerce: A case study of college students at a Romanian public university. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supianti, F. A panel data regression analysis for economic growth rate in Bengkulu Province. J. Stat. Data Sci. 2023, 2, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, B.; Mustafa, H. Empirical inspection of broadband growth nexus: A fixed effect with driscoll and Kraay standard errors approach. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2014, 8, 1–10. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/188121/1/pjcss156.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Overview of R and RStudio. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T. Technological Achievements and Economic Development: The Significance of Technological Achievement Gap in Selected East and South Asian Countries. STI Policy Rev. 2017, 8, 133–156. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319269548_Technological_Achievements_and_Economic_Development_The_Significance_of_Technological_Achievement_Gap_in_Selected_East_and_South_Asian_Countries (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Lumley, T.; Diehr, P.; Emerson, S.; Chen, L. The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2002, 23, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.F.; Finan, C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 98, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.G.; Kim, J.H. Central limit theorem: The cornerstone of modern statistics. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magsalay, R.J.M. Quantifying Central Limit Theorem Convergence: A Monte Carlo Simulation Approach to Minimum Sample Size. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2025, 9, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://ipcid.org/evaluation/apoio/Wooldridge%20-%20Cross-section%20and%20Panel%20Data.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

| Dimensions | Sub-Indicators | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating new technologies (CNT) | Total patent grants | WIPO statistics database https://www3.wipo.int/ipstats/ips-search/patent (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Number of patents officially granted, showing a country’s capacity to generate original technological innovations. |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property, receipts (BoP, current US$) | World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.GSR.ROYL.CD?name_desc=true (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Income from foreign entities paying for the use of domestic patents, trademarks, or copyrights, indicating global demand for local innovations. | |

| Diffusion of new technologies (DNT) | Individuals using the Internet (% of population) | World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?end=2023&most_recent_year_desc=true&start=1990 (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Shows how widely internet technology is adopted by the population, serving as a proxy for access to digital infrastructure. |

| High-technology exports (%) | World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.TECH.MF.ZS?end=2022&most_recent_year_desc=true&start=2007 (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Share of manufactured exports that are high-tech products, reflecting how successfully a country commercializes advanced technologies. | |

| Diffusion of old technologies (DOT) | Fixed telephone subscriptions (per 100 people) + Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people) | World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.MLT.MAIN.P2?most_recent_year_desc=true (accessed on 27 June 2025) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS.P2?most_recent_year_desc=true (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Represents the penetration of older communication technologies, signalling general connectivity and basic technological infrastructure. |

| Final consumption—households—energy use—Gigawatt-hour | Eurostat https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_CB_E (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Measures household energy consumption, a general indicator of technological appliance use and electrification. | |

| Development of human skills (DHS) | Gross enrolment ratio, primary to tertiary, both sexes (%) | UNESCO Institute for Statistics https://databrowser.uis.unesco.org/view#dicatorPaths=&geoMode=countries&geoUnits=&timeMode=range&view=table&chartMode=multiple&chartHighlightSeries=&chartHighlightEnabled=true&indicatorPaths=UIS-EducationOPRI%3A0%3AGER.1T8 (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Reflects educational participation across all levels, indicating the potential human capital available to support and adapt to technological progress. |

| Scientific and technical journal articles | World Bank Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IP.JRN.ARTC.SC?most_recent_year_desc=true (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Number of peer-reviewed publications, illustrating research output and the creation and dissemination of scientific knowledge. | |

| Control of Corruption (CC) | - | Worldwide Governance Indicators https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Assesses the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption. |

| Government Effectiveness (GE) | - | Worldwide Governance Indicators https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 27 June 2025) | The quality of public services, civil service, policy formulation, and implementation, reflects overall institutional performance. |

| Rule of Law (RL) | - | Worldwide Governance Indicators https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 27 June 2025) | Confidence in and adherence to the legal system, including contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts. |

| Regulatory Quality (RQ) | - | Worldwide Governance Indicators https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 27 June 2025) | The ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 25.415929 | 1.073930 | 23.6663 | <2.2× 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.78 | −2.820349 | 0.533095 | −5.2905 | 1.922 × 10−7 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 2.80 | −0.960411 | 0.484250 | −1.9833 | 0.04795 | * |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 1.71 | −1.255096 | 1.597236 | −0.7858 | 0.43241 | |

| Old.Technology.Difusion | 2.56 | −0.371567 | 1.285490 | −0.2890 | 0.77268 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.72 | −7.200401 | 1.612503 | −4.4654 | 1.016 × 10−5 | *** |

| 0.606 |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 25.26993 | 0.674212 | 37.4807 | <2.2 × 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.78 | −2.81483 | 0.514624 | −5.4697 | 7.54 × 10−8 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 2.8 | −0.98262 | 0.478786 | −2.0523 | 0.04073 | * |

| New.Technology.Difusion | 1.71 | −1.31917 | 1.699324 | −0.7763 | 0.43799 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.72 | −7.20776 | 1.61594 | −4.4604 | 1.04 × 10−5 | *** |

| 0.606 |

| Variable | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 24.965055 | 0.791486 | 31.542 | <2.2 × 10−16 | *** | |

| Control.of.Corruption | 1.16 | −2.937641 | 0.476049 | −6.1709 | 1.53 × 10−9 | *** |

| New.Technology.Creation | 1.63 | −0.717695 | 0.756844 | −0.9483 | 0.3435 | |

| Development.of.human.skills | 1.71 | −7.11983 | 1.694219 | −4.2024 | 3.19 × 10−5 | *** |

| 0.602 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mastac, L.; Mișa, A. Modelling the Shadow Economy: An Econometric Study of Technology Development and Institutional Quality. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243914

Mastac L, Mișa A. Modelling the Shadow Economy: An Econometric Study of Technology Development and Institutional Quality. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243914

Chicago/Turabian StyleMastac, Lavinia, and Anamaria Mișa. 2025. "Modelling the Shadow Economy: An Econometric Study of Technology Development and Institutional Quality" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243914

APA StyleMastac, L., & Mișa, A. (2025). Modelling the Shadow Economy: An Econometric Study of Technology Development and Institutional Quality. Mathematics, 13(24), 3914. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243914