Integrating Cognitive, Symbolic, and Neural Approaches to Story Generation: A Review on the METATRON Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Coherence: The logical connectivity and relevance between events in the story. A coherent story is one in which each event follows meaningfully from previous events.

- Cohesion: The local fluidity and fluency of the text, including grammatical correctness and appropriate use of referential links (e.g., pronouns, conjunctions). This is often referred to simply as fluency.

- Consistency: The adherence to established facts or rules within the story world and the preservation of character attributes or story facts over time. A consistent story does not violate its own established logic (e.g., a character’s behavior remains believable given what we know about them, or a previously dead character does not suddenly reappear without explanation).

- Novelty: The creativity or originality of the story, often measured in terms of avoiding redundant or cliched content. In computational terms, novelty is sometimes approximated by the diversity of generated text (e.g., using metrics like the proportion of unique n-grams).

- Interestingness: The level of engagement or emotional impact the story can evoke in a reader. This is a highly subjective quality, associated with the story’s ability to surprise, entertain, or provoke thought. Few works attempt to explicitly optimize or measure interestingness, as it is difficult to quantify.

2. State of the Art

2.1. Symbolic Approaches to Story Generation

2.2. Neural Approaches to Story Generation

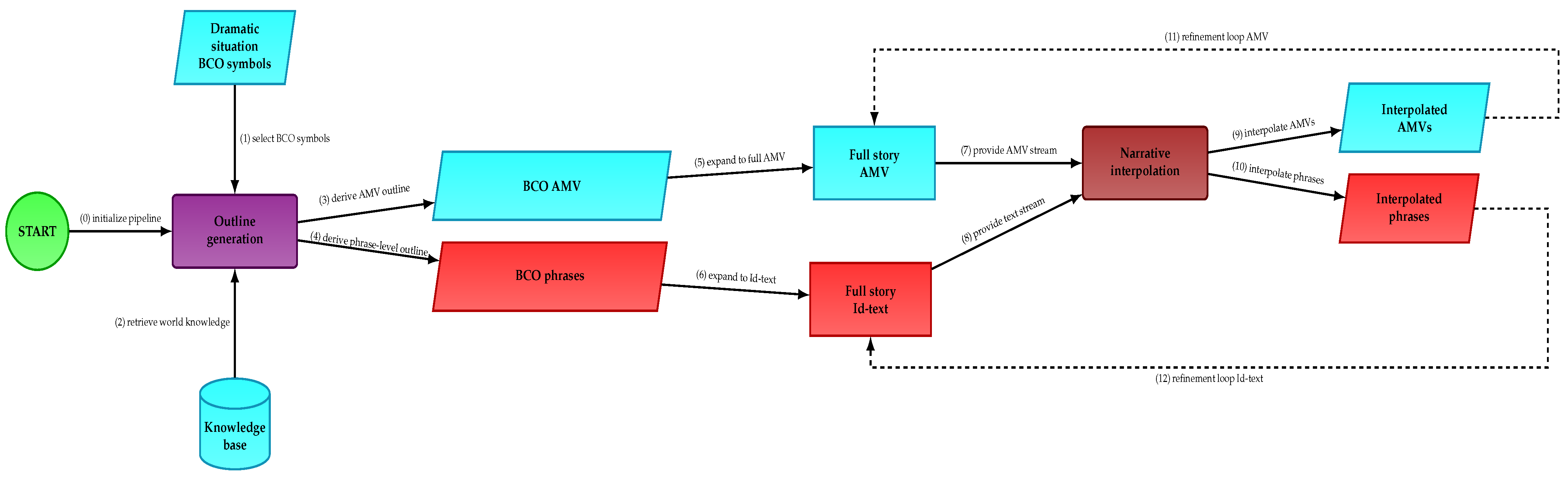

3. The METATRON Framework

3.1. General Architecture of the METATRON Framework

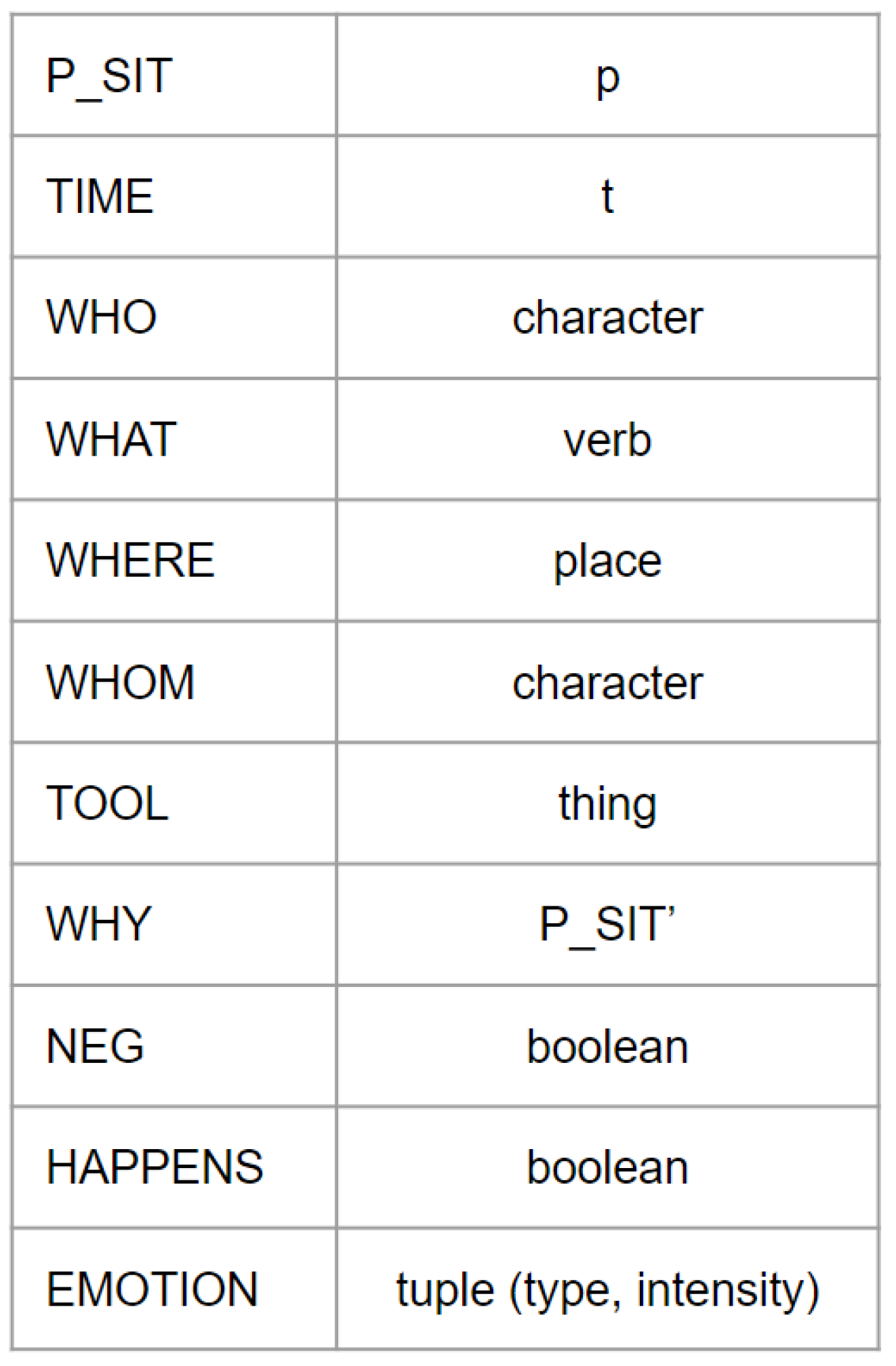

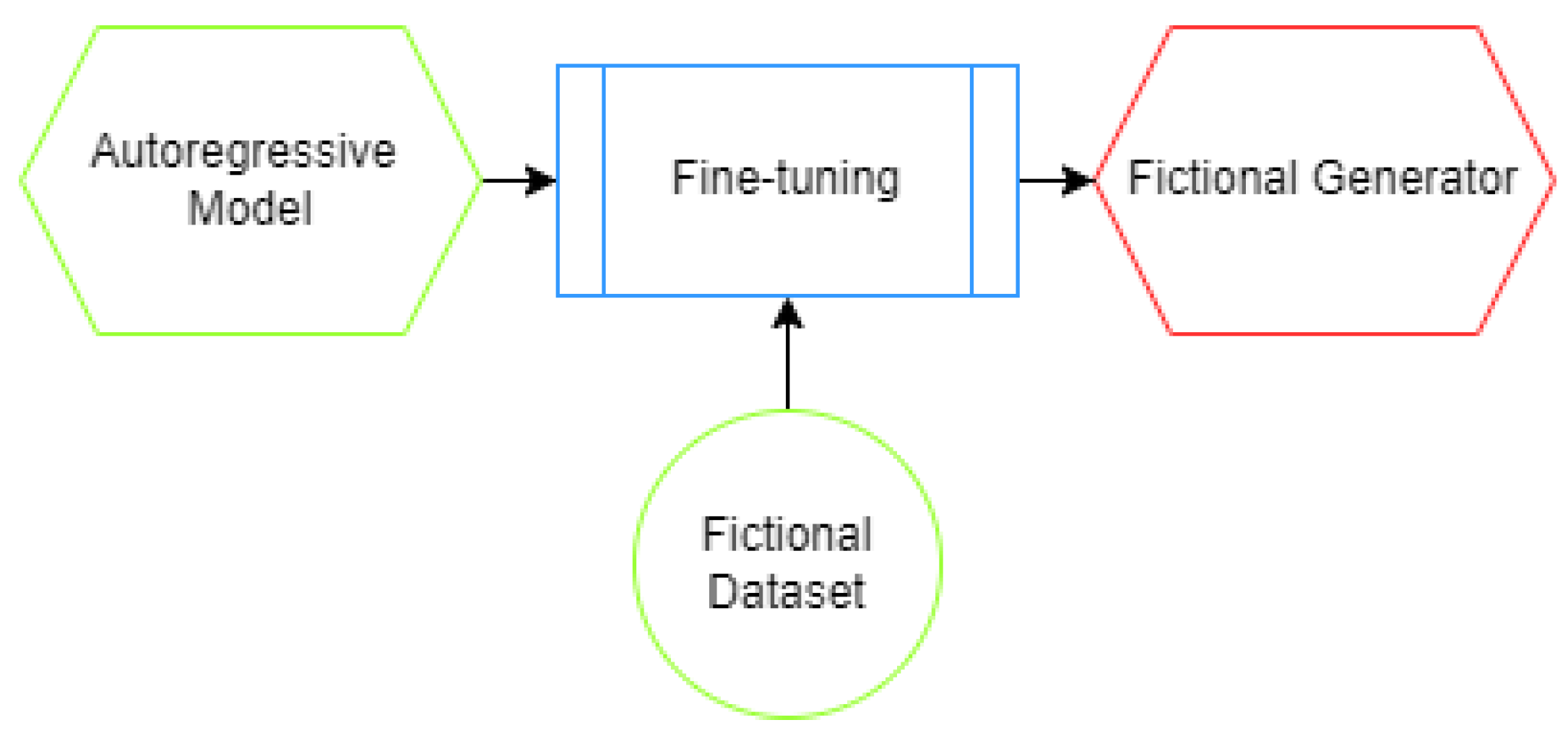

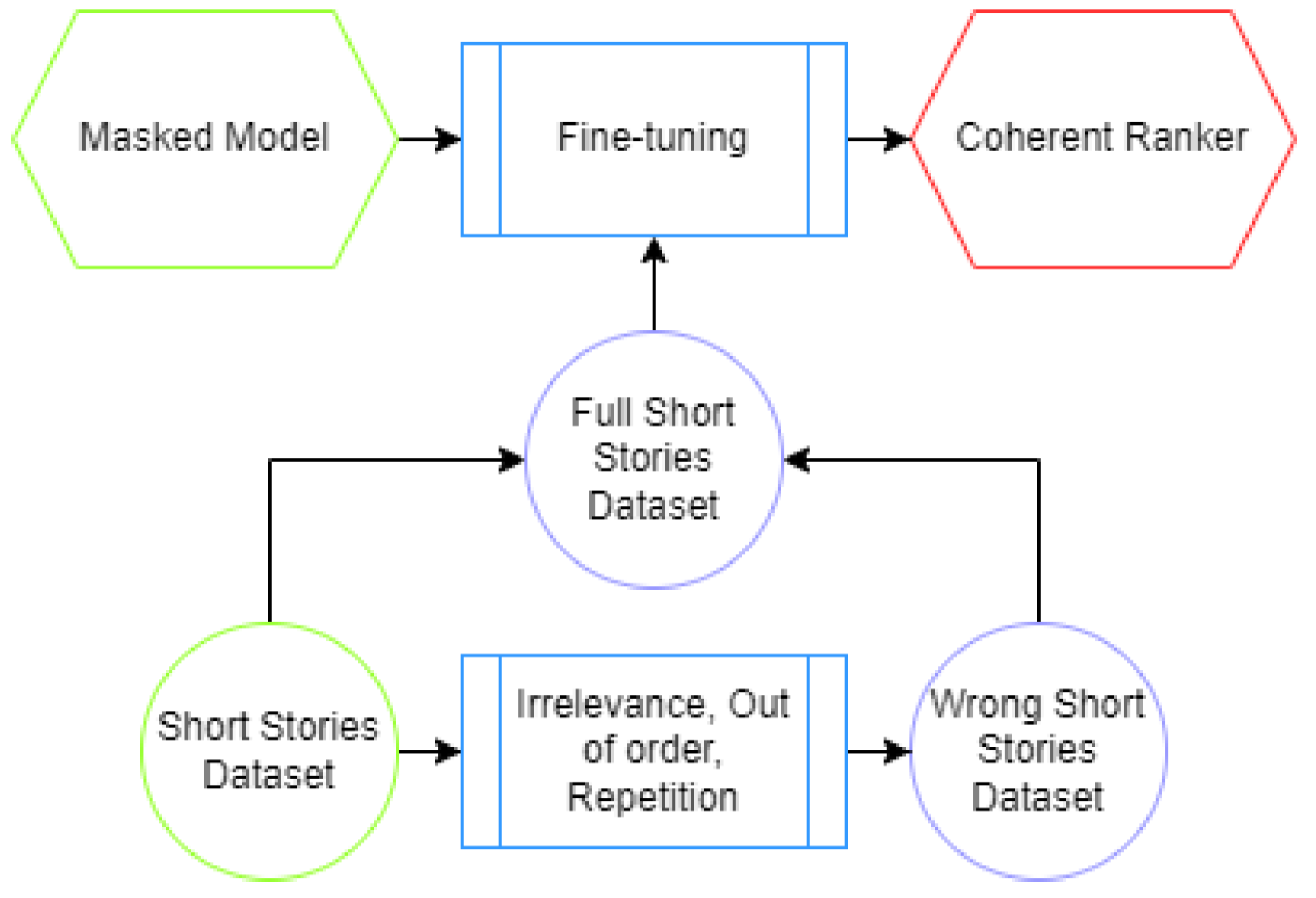

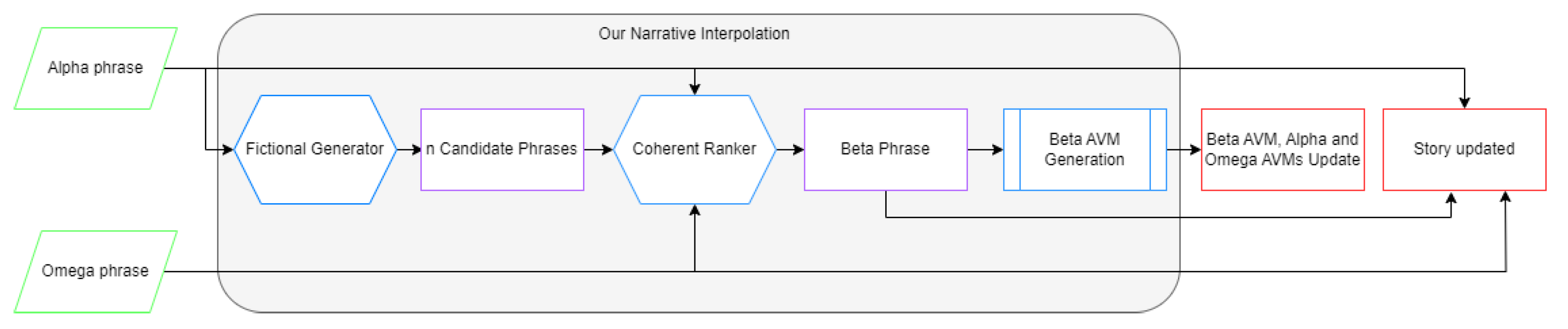

3.2. Module’s Description

- SituationType: one of Polti’s 36 dramatic situations (and possible subtype).

- Characters: roles involved (e.g., Protagonist, Antagonist, Victim).

- Setting: the environment or location where the situation unfolds.

- Object: a key element or MacGuffin central to the situation.

- Action: the core event or interaction (e.g., Revenge, Rescue, Seduction).

- Why: a causal or motivational link to other situations or backstory elements.

- When: temporal ordering or dependency (e.g., occurring after another situation).

- Emotion: the dominant affective tone (e.g., jealousy, betrayal, sacrifice).

- Outcome: a label indicating whether the AVM represents a beginning, climax, or resolution within the overall story arc.

- Beginning: “A <Fugitive> is on the run after committing <Crime>, and the <Authority> has dispatched a relentless <Pursuer> to hunt them down.”

- Climax: “The chase leads them to <Climactic Setting>, where the <Pursuer> corners the <Fugitive> amid rising tension and a crowd of onlookers.”

- Outcome: “In the end, <Outcome of Pursuit>—the <Fugitive> is brought to justice, and the long pursuit reaches its conclusion.”

- Positive Dataset: A collection of coherent story triples (previous sentence, candidate sentence, next sentence) drawn from real narratives. For this purpose, corpora such as ROCStories (short commonsense stories) and WritingPrompts (longer, creative stories from Reddit) are often used. Sequences of three consecutive sentences are extracted from these stories, and the middle sentence is treated as a “good” candidate given its neighboring context.

- Negative Dataset: A set of incoherent triples generated by introducing controlled perturbations into authentic stories, following the approach of Wang et al. [28]. These perturbations include:

- –

- Shuffling: Selecting three consecutive sentences from a story but replacing or swapping the middle one with a sentence from a different location, thus breaking logical continuity.

- –

- Irrelevant Insertion: Inserting a random sentence—taken from another story or context—between two adjacent sentences, typically introducing unrelated entities or topics.

- –

- Repetition: Reusing the preceding sentence or part of it as the middle sentence, modeling incoherence caused by redundancy (a phenomenon often flagged by human evaluators as poor narrative flow).

- –

- Contradiction/Opposition: Introducing a middle sentence that contradicts its context (e.g., if the first sentence states “John was alive,” a contradictory continuation might read “Everyone was mourning John’s death”). Such oppositions produce clearly inconsistent narrative segments.

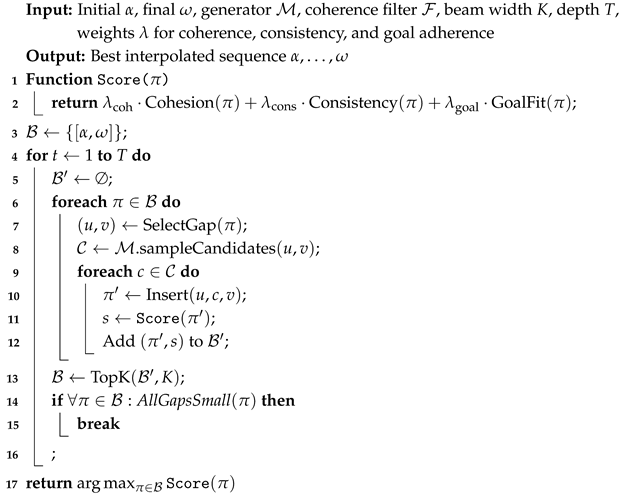

| Algorithm 1: Greedy Narrative Interpolation |

|

| Algorithm 2: Narrative Interpolation with Beam Search and Re-Scoring |

|

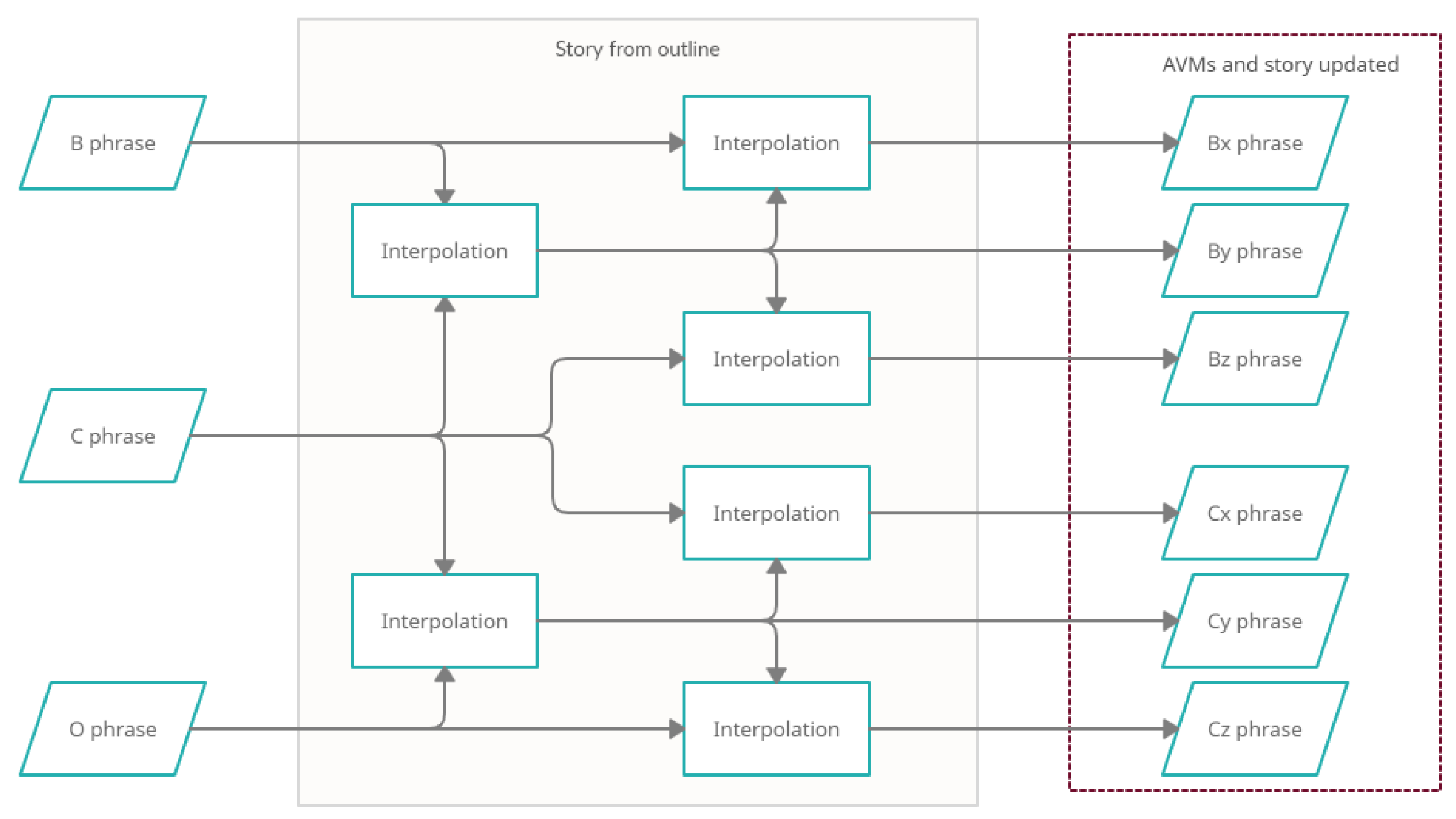

3.3. Full Story Generation and Multimodal Extension

3.4. A Neurosymbolic Approach

- The AVM and BCO generator ensure that at a high level, the story follows a meaningful dramatic arc (so we won’t get a nonsensical sequence of events; there’s an underlying human-vetted narrative pattern).

- The neural generator ensures that the prose of the story is natural and potentially creative or unexpected (thus improving novelty and fluency).

- The coherence filter acts as a symbolic constraint engine (though learned) to enforce logical transitions, effectively acting like a narrative rule- checker albeit implemented as a neural network. It embodies symbolic logic in its training data design.

- The emotion model injects a cognitive dimension: it treats the story as not just a sequence of events but as an affective journey. This draws on psychological theories of emotion and can be seen as a symbolic layer overlaying the text (each event is tagged with emotional significance).

- The use of Polti’s situations is essentially encoding human literary knowledge (a symbolic knowledge base) into the generative process, which is something a purely neural model pre-trained on text might not explicitly have, or might not reliably use.

3.5. Novelty and Distinguishing Features of the Approach

- Integration of classical dramatic theory. Rather than relying solely on loosely defined schemas or crowd-sourced plot fragments, the design explicitly incorporates comprehensive dramaturgical taxonomies such as Polti’s thirty-six situations [42,43], in dialog with structuralist accounts like Propp’s morphology [55]. Leveraging these taxonomies injects long-standing theoretical insight into computational storytelling, offering structural richness and systematic coverage of narrative space (36 situations × 3 phases = 108 templates) while promoting diversity beyond generic adventure templates [8,9,32,56].

- Cognitive-oriented emotion regulation. Emotion is represented and controlled as an explicit signal (valence, intensity, and basic categories), enabling targeted arcs and pacing at the sentence or scene level; this extends prior work on protagonist emotions and narrative affect [27,57] and is conceptually grounded in cognitive and neural perspectives [50], connecting to broader creativity discussions in AI [58].

- Neurosymbolic coherence filtering. Local coherence is assessed iteratively during generation using masked-LM style discriminators, advancing beyond pairwise sentence checks and narrative interpolation setups [17,28]. Triple-based scoring captures bidirectional constraints (previous–candidate–next) and integrates tightly with symbolic state tracking and entity representations [18,22], aligning with planning-centric traditions in narrative control [6,10,33].

- Multimodal narrative generation. The architecture is compatible with visual and audio synthesis, building on visual storytelling [59] and recent diffusion-based imagery [51], and extending toward sound and music generation for scene-setting [52,53,54,60]. This broadens storytelling from purely verbal narration toward scene-direction capabilities.

- Hybrid use of large language models (LLMs). LLMs are positioned as guided components within a neurosymbolic scaffold rather than free-running narrators, addressing long-context limitations [11,13,23,34,61] and echoing recent perspectives that use LLMs as planners or search guides inside narrative systems [35,36,62]. This stance complements earlier plan-and-write and controllability lines [4,15,21,24,63].

- Evaluation perspectives. Beyond readability or surface coherence, the evaluation program emphasizes cognitively meaningful tests, including theory-of-mind style probes and consistency under commonsense constraints [47,64,65], as well as creativity-oriented assessments [66]. These criteria situate the approach within established surveys and state-of-the-art mappings [37,67,68,69].

3.6. Evaluation Methodology

- Automatic metrics (initial stage). Current automatic metrics remain limited: perplexity approximates fluency under a reference language model; lexical diversity is commonly measured with Distinct-n for [4]; and descriptive indicators such as average story length or the positional distribution of emotionally valenced terms can help diagnose intended affective arcs. Coherence can be approximated by segmenting stories into triples (previous–candidate–next) and scoring them with a trained coherence filter, although no single metric reliably captures global structure. In the early stages of system development, these proxy metrics serve primarily as diagnostics rather than substitutes for human evaluation.

- Human evaluation (ground truth). Because reliable automatic measures of coherence, creativity, emotional resonance, and theory-of-mind reasoning are still lacking, human judgment remains the ground truth for validating narrative quality. Reader studies typically collect Likert ratings along several dimensions: cohesion/fluency (sentence-level readability), coherence (global sense-making), consistency (continuity of characters and world facts), engagement (subjective interest), and creativity (originality and avoidance of clichés). Pairwise preference tests can compare METATRON outputs with baseline systems (e.g., prompt-only LLMs or symbolic planners). A theory-of-mind consistency test can further check whether characters’ actions align with their knowledge and beliefs across the narrative.

- Toward reduced human intervention (LLM-as-judge). Over time, human evaluations can be used to calibrate large language models as approximate judges of narrative quality, following approaches in recent work on LLM-based evaluators (e.g., Literary Language Mashup). Once sufficient correlation with human judgments is established, LLM-based evaluation can partially replace human raters for routine benchmarking. In this sense, human judgment is required at the initial validation stage, but the long-term aim is to derive stable, automatically computable proxies that progressively reduce the need for human intervention in large-scale evaluation.

4. Controllable Narrative Generation and Symbolic Guidance in LLMs

- Schema and Plot Graphs: Earlier systems like GESTER [70] or STORY GRAMMARS tried to use schemas that define what sequences of plot functions can occur. Vladimir Propp’s morphology of the folktale [55] is a famous example of a story schema (with functions like “villainy”, “donor test”, “hero’s victory”, etc.). These are symbolic structures that, if enforced, guarantee a certain kind of story (e.g., a fairy tale structure). Modern analogues include plot graphs or story domains, where authors define possible event sequences in a planning domain language [37]. Our use of Polti is akin to a high-level schema selection. We could in the future refine it to more detailed schemas (like sequences of Polti situations or sub-situations).

- Conditional Generation with Outlines: As discussed in state- of-the-art, models like Fan et al. [16] accept an outline or prompt that lists key events or constraints. The large model then fills in the details. This is a simple form of control: you steer via the input. In our pipeline, we essentially produce such an outline automatically (BCO sentences) and then ensure the generated story adheres to them (through the coherence filter that anchors on the outline points). This means we can achieve similar controllability as providing a human-written outline, but without human effort, because the outline is generated by our Polti-based module.

- Vector-based Control and Prompt Engineering: With models like GPT-3, one popular approach has been to craft the prompt cleverly to encode constraints. For example, one can instruct the model step by step: “First, list the main points of the story that involve a detective solving a crime. Then narrate the story following those points.” This often yields a more structured output. This insight aligns with our method: by explicitly separating planning (points) from narration, we control the outcome better. Some works have used prefix tuning or PPLM where an attribute model steers the generation by nudging the hidden states. For instance, Dathathri et al. [73] could steer the topic or sentiment of generated text by adding gradients from a classifier. In principle, one could train a “narrative arc” classifier and use PPLM to enforce, say, “make sure this stays a mystery story, don’t turn into comedy”. However, these methods, while elegant, can be brittle and are less interpretable than symbolic control.

- Hybrid Planner-LLM Systems: Recently, Xiang et al. [35] demonstrated an approach where a classical symbolic planner (like one that generates a sequence of high-level actions using a domain definition and goals) is interleaved with a neural LLM (GPT-3) that turns each plan step into a paragraph of story. They applied this to the old TALE-SPIN domain. The planner ensures logical progression (characters only do things allowed in the domain and needed to achieve goals), while GPT-3 adds richness. This is very analogous to our architecture, except our “planner” is simpler (choose a Polti situation and BCO outline rather than planning each step of a character’s plan). The success of Xiang et al.’s system [35] is promising: they found that the combined system wrote more coherent stories than GPT-3 alone, and often more interesting ones than the planner alone (which was very dry). This validates the neurosymbolic approach. It also underscores that large LMs can be used in a controlled pipeline rather than just free generation. Another hybrid example is Farrell and Ware [36], who used an LLM to guide a search in narrative planning: essentially, the LLM suggests which branches of the story tree are promising (like a heuristic) and the planner ensures validity. This improved the efficiency and creativity of the planner’s output without sacrificing coherence. These works show that symbolic control at macro-level combined with neural fluency at micro-level is a fruitful direction.

Narrative Controllability and Symbolic Guidance

5. Episodic Memory and Emotional Modeling in Story Generation

5.1. Memory as Narrative Structure and Constraint

Mechanisms for Memory Retention

5.2. Emotional Modeling and Affective Trajectories

Interplay of Emotion and Memory

6. Cognitive and Creative Dimensions of AI-Generated Narratives

6.1. Theory of Mind in AI Narratives

6.2. Operationalizing Theory of Mind Within the METATRON Framework

Alpha: “Lara hides the key in the red box while Marco is outside.” Omega: “Marco returns and searches for the key.”

“Unaware of its new location, Marco checks the drawer first.”

“Marco heads straight to the red box, knowing the key is inside.”

“Anna believes that Ben thinks the diary is locked in the desk. In fact, only Anna knows it was moved to the attic.”

Alpha: “Ruth avoided speaking about the accident at dinner.” Omega: “She later apologized to Eli.”

- Belief-tag accuracy (BTA): For each character, METATRON maintains a belief-state graph. After story generation, an LLM-based evaluator answers questions of the form “Does character X know Y?”. Ground truth is determined by the symbolic state tracker. BTA is the percentage of questions answered correctly.

- Epistemic contradiction rate (ECR): The proportion of sentences in which a character acts on information they do not possess. Lower is better.

- Perspective drift score (PDS): Measures unintended switches in narrative viewpoint between adjacent sentences (0 = no drift).

- Coherence under perturbation (CUP): Following Ullman [83], minimal changes are introduced (e.g., swapping object locations); the system is scored on whether character beliefs update consistently.

- creativity of the twist or conflict resolution,

- maintenance of ToM consistency across long-distance dependencies,

- degree of novel yet plausible emotional inference.

Interpretation Within METATRON

6.3. The Lovelace Test and Computational Creativity

6.4. Lovelace-Style Probes Tailored to METATRON

- Lexical avoidance constraints. The system must realize a given dramatic situation (e.g., Polti’s Pursuit) while avoiding a list of taboo words (e.g., names of roles or key objects). Constraint satisfaction is measured as the fraction of outputs with zero taboo-token violations. To penalize trivial circumlocutions (e.g., simply omitting core concepts), judges rate whether the constraints were satisfied in a non-degenerate way (e.g., the forbidden concept is still clearly present at the semantic level).

- Conceptual fusion constraints. Prompts specify two or more disparate concepts (e.g., “a betrayal that ends in an unexpected act of kindness” or “a courtroom drama with fairies and quantum computers”), and require mapping them into a single Polti situation. We measure fusion success as the percentage of stories where human raters agree that all requested elements are meaningfully integrated rather than mentioned in isolation. This follows the spirit of Riedl [66] in emphasizing non-trivial satisfaction of combined constraints.

- Affective-structural constraints. Here the prompt enforces a target emotional arc (e.g., neutral → fear → relief) in combination with a particular dramatic situation. METATRON’s explicit emotion tags allow computation of an arc adherence score: the correlation between the intended valence trajectory and the predicted trajectory from an emotion classifier applied to the generated text [57]. Creative success requires both structural compliance and an engaging, non-formulaic realization.

6.4.1. Quantifiable Creativity Metrics

- Constraint satisfaction rate (CSR). Proportion of generated stories that satisfy all hard constraints (lexical, structural, or affective). This directly captures the Lovelace 2.0 requirement that outputs respect user-imposed conditions.

- Non-triviality score (NTS). Following Riedl [66], human or LLM-based judges rate on a Likert scale whether a story’s solution to the constraints is “obvious” (e.g., trivial insertion of keywords) or shows a degree of indirectness, metaphor, or inventiveness. Higher scores indicate more genuinely creative responses.

- Originality and diversity indices. Across a batch of stories generated under the same constraints, we compute Distinct-n, type-token ratios for content words, and clustering of AVM instantiations (e.g., diversity of character roles and settings) [87]. A system that repeatedly falls back to the same combinations of roles or scenes would exhibit low structural diversity even if surface wording varies.

- Surprise under a baseline model. Given a reference language model or n-gram proxy trained on a background corpus, we approximate how unexpected METATRON’s stories are by computing normalized inverse likelihood or information content. Moderately higher surprise (without degeneracy) is taken as a signature of originality, distinguishing creative constraint-satisfying outputs from rote reproductions.

6.4.2. Integrating Lovelace 2.0 with Neurosymbolic Ablations

- A baseline LLM prompted directly with constraints, and

- The full neurosymbolic pipeline where constraints are encoded at the AVM/BCO levels.

6.5. Human-like Cognitive Abilities in Narratives

6.6. Creativity, Control, and Cognitive Realism

6.7. Toward Integrative Evaluation of Cognitive and Creative Dimensions

7. Architectural Challenges and Practical Considerations

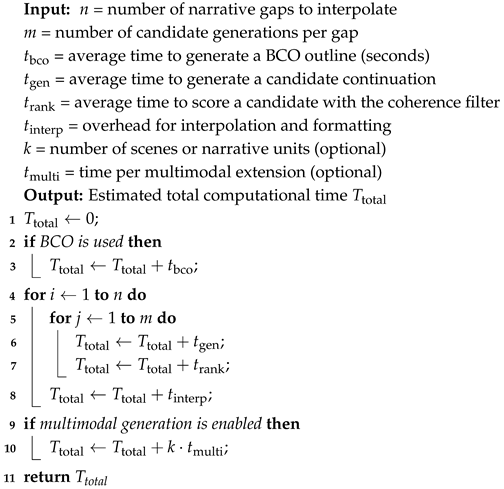

| Algorithm 3: Estimate Computational Overhead |

|

7.1. Computational Efficiency

7.2. Error Propagation and Robustness

7.3. Scalability to Longer Narratives

7.4. Illustrative Example: Overhead Estimation

- s for generating the full BCO outline with a symbolic prompt to GPT-4.

- s per candidate continuation (again using a GPT-class model).

- s per reranking pass using a BERT-based coherence model.

- s per interpolation formatting and integration.

- s per image or audio generation using a model like SDXL or AudioGen.

- s per interpolation formatting and integration.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AVM | Attribute–Value Matrix |

| BCO | Beginning, Climax, and Outcome structure |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| DOME | Dynamic Outline Model for Evaluation |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SWC | Story–World Context |

| ToM | Theory of Mind |

References

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rukeyser, M. The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, M. A knowledge-enhanced pretraining model for commonsense story generation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Galley, M.; Brockett, C.; Gao, J.; Dolan, B. A diversity-promoting objective function for neural conversation models. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2016, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, J.R. TALE-SPIN, an interactive program that writes stories. In Proceedings of the 5th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Cambridge, MA, USA, 22–25 August 1977; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz, M. Planning stories. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–18 July 1987; pp. 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.R. MINSTREL: A Computer Model of Creativity in Storytelling. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.R. The Creative Process: A Computer Model of Storytelling and Creativity; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-y-Pérez, R.; Sharples, M. MEXICA: A computer model of a cognitive account of creative writing. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2001, 13, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, M.O.; Young, R.M. Narrative planning: Balancing plot and character. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2010, 39, 217–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30, pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Better Language Models and Their Implications. OpenAI Technical Report. 2019. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/better-language-models/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Ammanabrolu, P.; Riedl, M.O. Playing Text-Adventure Games with Graph-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–5 June 2019; pp. 3557–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Peng, N.; Weischedel, R.; Knight, K.; Zhao, D.; Yan, R. Plan-and-write: Towards better automatic storytelling. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 7378–7385. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; Lewis, M.; Dauphin, Y. Strategies for structuring story generation. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 2650–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Durrett, G.; Erk, K. Narrative interpolation for generating and understanding stories. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.07466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Ji, Y.; Smith, N.A. Neural text generation in stories using entity representations as context. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 2250–2260. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Agrawal, P.; Mishra, A. Story generation from sequence of independent short descriptions. In Proceedings of the SIGKDD Workshop on Machine Learning for Creativity (ML4Creativity), Halifax, NS, Canada, 14 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ammanabrolu, P.; Tien, E.; Cheung, W.; Luo, Z.; Ma, W.; Martin, L.J.; Riedl, M.O. Story realization: Expanding plot events into sentences. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Puri, R.; Fung, P.; Anandkumar, A.; Catanzaro, B. MEGATRON-CNTRL: Controllable story generation with external knowledge using large-scale language models. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 2831–2845. [Google Scholar]

- Rashkin, H.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Choi, Y.; Gao, J. PlotMachines: Outline-Conditioned Generation with Dynamic Plot State Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 4274–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.F.; Lin, K.; Hewitt, J.; Paranjape, A.; Bevilacqua, M.; Jia, R.; Liang, P.; Manning, C.D. Lost in the middle: How language models use long contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; May, J.; Knight, K. Towards controllable story generation. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Storytelling, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5 June 2018; pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tambwekar, P.; Dhuliawala, M.; Martin, L.; Mehta, A.; Harrison, B.; Riedl, M.O. Controllable neural story plot generation via reward shaping. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 5982–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Xu, Z.; Liu, T.; Chang, B.; Sui, Z. Learning to control the fine-grained sentiment for story ending generation. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 6020–6026. [Google Scholar]

- Brahman, F.; Chaturvedi, S. Modeling protagonist emotions for emotion-aware storytelling. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 5277–5294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Li, P.; Zheng, H. Consistency and coherency enhanced story generation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, 28 March–1 April 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ammanabrolu, P.; Riedl, M.O. Learning Knowledge Graph-based World Models of Textual Environments. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2021, Online, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bosselut, A.; Rashkin, H.; Sap, M.; Malaviya, C.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Choi, Y. COMET: Commonsense Transformers for Automatic Knowledge Graph Construction. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2019), Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 4762–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammanabrolu, P.; Riedl, M.O. Modeling worlds in text. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- y Pérez, R.P.; Sharples, M. Three computer-based models of storytelling: BRUTUS, MINSTREL and MEXICA. Knowl. Based Syst. 2004, 17, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteous, J.; Cavazza, M. Controlling narrative generation with planning trajectories: The role of constraints. In Proceedings of the ICIDS 2009: Interactive Storytelling, Berlin, Germany, 9–11 December 2009; pp. 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Carbonell, J.G.; Le, Q.; Salakhutdinov, R. Transformer-XL: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 2978–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, M.; McKenzie, M.; Kilayko, A.; Macbeth, J.C.; Carter, S.; Sieck, K.; Klenk, M. Interleaving a symbolic story generator with a neural network-based large language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cognitive Systems Conference, Arlington, VA, USA, 19–22 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, R.; Ware, S.G. Large Language Models as Narrative Planning Search Guides. IEEE Trans. Games 2025, 17, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, S.G.; Young, R.M. Glaive: A State-Space Narrative Planner Supporting Intentionality and Conflict. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Québec, QC, Canada, 27–31 July 2014; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 957–964. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Ge, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Shan, Y.; Chen, Y. SEED-Story: Multimodal Long Story Generation with Large Language Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhong, X. StoryLLaVA: Enhancing Visual Storytelling with Multi-Modal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, UAE, 19–24 January 2025; Rambow, O., Wanner, L., Apidianaki, M., Al-Khalifa, H., Di Eugenio, B., Schockaert, S., Eds.; International Committee on Computational Linguistics (ICCL). 2025; pp. 3936–3951. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Pan, R.; Li, H. StoryBox: Collaborative Multi-Agent Simulation for Hybrid Bottom-Up Long-Form Story Generation Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.A.; Vainbrand, D.; Kashinkunti, P.; Bernauer, J.; Catanzaro, B.; et al. Efficient large-scale language model training on GPU clusters using Megatron-LM. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.04473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polti, G. Les 36 Situations Dramatiques; Mercure de France: Paris, France, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Figgis, M. The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations; Faber and Faber: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. A Framework for Representing Knowledge. In The Psychology of Computer Vision; Winston, P., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 211–277. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, H.; Gelbukh, A. Recognizing Situation Patterns from Self-Contained Stories. In Proceedings of the Advances in Natural Language Understanding and Intelligent Access to Textual Information: NLUIATI-2005 Workshop in conjunction with MICAI-2005, Monterrey, Mexico, 14–18 November 2005; Gelbukh, A., Gómez, M.M., Eds.; Research in Computing Science. Center for Computing Research, IPN: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gelbukh, A.; Calvo, H. Second Approach: Constituent Grammars. In Automatic Syntactic Analysis Based on Selectional Preferences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafazadeh, N.; Chambers, N.; He, X.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D.; Vanderwende, L.; Kohli, P.; Allen, J. A corpus and evaluation framework for deeper understanding of commonsense stories. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 6 January 2016; pp. 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 3–5 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, E.R.; Koester, J.D.; Mack, S.H.; Siegelbaum, S.A. Principles of Neural Science, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Jeong, S.; Kang, S.; Han, N.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, T. Sound of story: Multi-modal storytelling with audio. In Proceedings of the Findings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 13465–13479. [Google Scholar]

- Agostinelli, A.; Borsos, Z.; Engel, J.; Verzetti, M.; Le, Q.V.; Adi, Y.; Acher, M.; Saharia, C.; Chan, W.; Tagliasacchi, M. MusicLM: Generating music from text. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuk, F.; Polyak, A.; Ridnik, T.; Sharir, E.; Paiss, R.; Lang, O.; Mosseri, I.; Ayalon, A.; Dorman, G.; Freedman, D. AudioGen: Textually guided audio generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.15352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, V. Morphology of the Folktale, 2nd ed.; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Gervás, P. Computational approaches to storytelling and creativity. AI Mag. 2014, 30, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, A.J.; Danforth, C.M.; Tivnan, B.; Williams, J.R.; Dodds, P.S. The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Sci. 2016, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.A. Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artif. Intell. 1998, 103, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.H.K.; Ferraro, F.; Mostafazadeh, N.; Misra, I.; Agrawal, A.; Devlin, J.; Girshick, R.; He, X.; Kohli, P.; Batra, D.; et al. Visual storytelling. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 6 June 2016; pp. 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copet, J.L.; Kreuk, F.; Gat, I.; Remez, T.; Kant, D.; Synnaeve, G.; Adi, Y.; Défossez, A. Simple and controllable music generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.05284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Puri, R.; LeGresley, P.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B. Megatron-LM: Training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.08053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, T.B.; Guu, K.; Oren, Y.; Liang, P. A retrieve-and-edit framework for predicting structured outputs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Volume 31, pp. 10073–10083. [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski, M. Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.02083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, M. Evaluating large language models in theory-of-mind tasks. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2405460121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, M.O. The Lovelace 2.0 Test of Artificial Creativity and Intelligence. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1410.6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHussain, A.I.; Azmi, A.M. Automatic story generation: A survey of approaches. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 103:1–103:38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulkarim, A.; Li, S.; Peng, X. Automatic story generation: Challenges and attempts. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Narrative Understanding (NUSE), Virtual, 11 June 2021; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kachare, A.H.; Kalla, M.; Gupta, A. A review: Automatic short story generation. Seybold Rep. 2022, 17, 1818–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton, L. A Modular Approach to Story Generation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Manchester, UK, 10–12 April 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; Lewis, M.; Dauphin, Y. Hierarchical neural story generation. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bing, L.; Qiu, L.; Chen, D.; Zhao, D.; Yan, R. Learning to write stories with thematic consistency and wording novelty. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dathathri, S.; Madotto, A.; Lan, J.; Hung, J.; Frank, E.; Molino, P.; Yosinski, J.; Liu, R. Plug and play language models: A simple approach to controlled text generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 30 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M.; Ware, S.G.; Cassell, B.A.; Robertson, J. Plans and planning in narrative generation: A review of plan-based approaches to the generation of story, discourse and interactivity in narratives. Sprache Datenverarb. Spec. Issue Form. Comput. Model. Narrat. 2013, 37, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Rivera, R.E.; Cassell, B.A.; Ware, S.G.; Young, R.M. Indexter: A computational model of the event-indexing situation model for characterizing narratives. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Computational Models of Narrative, Istanbul, Turkey, 26–27 May 2012; pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huet, A.; Houidi, Z.B.; Rossi, D. Episodic memories generation and evaluation benchmark for large language models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, J. Language Models as Agent Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 5769–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, M.O.; Harrison, B. Using stories to teach human values to artificial agents. In Proceedings of the 2nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Ethics, and Society, Madrid, Spain, 20–22 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, R.; Chin, J.; Havasi, C. ConceptNet 5.5: An open multilingual graph of general knowledge. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 4444–4451. [Google Scholar]

- Ilievski, F.; Oltramari, A.; Ma, K.; Zhang, B.; McGuinness, D.L.; Szekely, P. Dimensions of commonsense knowledge. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 229, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammanabrolu, P.; Cheung, W.; Broniec, W.; Riedl, M.O. Automated storytelling via causal, commonsense plot ordering. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 19–21 May 2021; Volume 35, pp. 5859–5867. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz, N.C.; Perbet, F.; Song, H.F.; Zhang, C.; Eslami, S.M.A.; Botvinick, M. Machine Theory of Mind. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4218–4227. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, T. Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.08399. [Google Scholar]

- Sap, M.; Rashkin, H.; Chen, D.; LeBras, R.; Choi, Y. SocialIQA: Commonsense reasoning about social interactions. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileo, D.; Lernould, A. Mindgames: Targeting theory of mind in large language models with dynamic epistemic modal logic. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.03353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Y.; He, R.; Mao, X.; Fan, C.; Huang, M. LOT: A Story-Centric Benchmark for Evaluating Chinese Long Text Understanding and Generation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 10, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanous, A. A Standardised Procedure for Evaluating Creative Systems: Computational Creativity Evaluation Based on What It Is to Be Creative. Cogn. Comput. 2012, 4, 246–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. In Proceedings of the NIPS Deep Learning and Representation Learning Workshop, Montréal, QC, Canada, 11 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a Distilled Version of BERT: Smaller, Faster, Cheaper and Lighter. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Workshop on Energy Efficient Machine Learning and Cognitive Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman, A.; Buys, J.; Du, L.; Forbes, M.; Choi, Y. The Curious Case of Neural Text Degeneration. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Virtual, 26 April–1 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Tian, Y.; Peng, N.; Klein, D. Re3: Generating longer stories with recursive reprompting and revision. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Klein, D.; Peng, N.; Tian, Y. DOC: Improving long story coherence with detailed outline control. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 3378–3465. [Google Scholar]

| Paradigm/System | Key References | Core Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations/ Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TALE-SPIN | Meehan [5] | Rule-based simulation of characters’ goals and problem-solving | Ensures causal logic; early model of narrative reasoning | Limited domain, rigid grammar, minimal stylistic variety |

| Author | Lebowitz [6] | Plot fragments and rule-based assembly | Genre control; domain-specific coherence | Highly handcrafted; low generalization |

| MINSTREL | Turner [7,8] | Case-based reasoning and transformational creativity | Adaptation of existing stories; explicit author goals | Requires detailed knowledge base; limited language output |

| MEXICA | Pérez-y-Pérez and Sharples [9], y Pérez and Sharples [32] | Engagement–reflection cognitive cycle with emotional tension modeling | Strong internal coherence and affective arcs | Domain-limited; manually designed action set |

| Narrative Planners (IPOCL, etc.) | Riedl and Young [10], Porteous and Cavazza [33] | Partial-order causal link planning with character intentions | Causal consistency and believable actions | Text realization often mechanical; computationally expensive |

| Plan-and-Write/Hierarchical Neural | Yao et al. [15], Fan et al. [16] | Two-stage neural pipeline: outline generation then realization | Better global focus than flat LMs; scalable with LLMs | Still prone to drift within long contexts |

| Knowledge-Augmented LMs | Guan et al. [3], Ammanabrolu and Riedl [14] | Integration of commonsense or script knowledge graphs | Improved logical coherence and causality | Limited by coverage and noise in external knowledge |

| INTERPOL | Wang et al. [17] | Generator–critic setup with coherence reranker (RoBERTa) | Removes incoherent continuations effectively | Requires multiple candidates; increases inference cost |

| Entity-Aware Generators | Clark et al. [18], Ammanabrolu et al. [20], Rashkin et al. [22] | Explicit entity or state representations during decoding | Consistent characters and references; mitigates “lost in the middle” | Additional complexity; entity drift not fully solved |

| Emotion- and Goal-Conditioned Models | Brahman and Chaturvedi [27], Luo et al. [26], Tambwekar et al. [25] | Conditioning via emotion trajectories or reinforcement learning rewards | Genre or mood control; dynamic affective pacing | Limited emotional taxonomies; unstable optimization |

| Large Language Models (GPT-2/3, etc.) | Vaswani et al. [11], Radford et al. [12], Brown et al. [13], Dai et al. [34] | Autoregressive Transformer trained on large-scale corpora | Fluent, stylistically rich text generation | Weak long-range coherence; memory and consistency issues |

| Hybrid/ Neurosymbolic | Xiang et al. [35], Farrell and Ware [36], Ware and Young [37] | Combination of symbolic planning and neural generation guided by coherence filters | Balances structure and fluency; explainable; extensible | Integration cost; evaluation frameworks still developing |

| Criterion | Symbolic | Neural | Neuro-Symbolic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coherence | High: follows explicit plot logic | Medium/Low: lacks structure, drifts | High: guided plots keep global structure |

| Consistency | High: no contradictions; explicit states | Low: frequent contradictions or drift | High: constraints avoid contradictions |

| Creativity | Low: rule-bound, formulaic | High: diverse, data-driven content | Medium: structured yet diverse |

| Prior Knowledge | Extensive: handcrafted rules/templates | Minimal: learned from data | Moderate: needs schemas plus pretraining |

| Scalability | Poor: domain-limited, brittle | High: general but context-limited | Moderate: scalable neural core, adaptable rules |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calvo, H.; Herrera-González, B.; Laureano, M.H. Integrating Cognitive, Symbolic, and Neural Approaches to Story Generation: A Review on the METATRON Framework. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233885

Calvo H, Herrera-González B, Laureano MH. Integrating Cognitive, Symbolic, and Neural Approaches to Story Generation: A Review on the METATRON Framework. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233885

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvo, Hiram, Brian Herrera-González, and Mayte H. Laureano. 2025. "Integrating Cognitive, Symbolic, and Neural Approaches to Story Generation: A Review on the METATRON Framework" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233885

APA StyleCalvo, H., Herrera-González, B., & Laureano, M. H. (2025). Integrating Cognitive, Symbolic, and Neural Approaches to Story Generation: A Review on the METATRON Framework. Mathematics, 13(23), 3885. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233885