Communication-Computation Co-Optimized Federated Learning for Efficient Large-Model Embedding Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

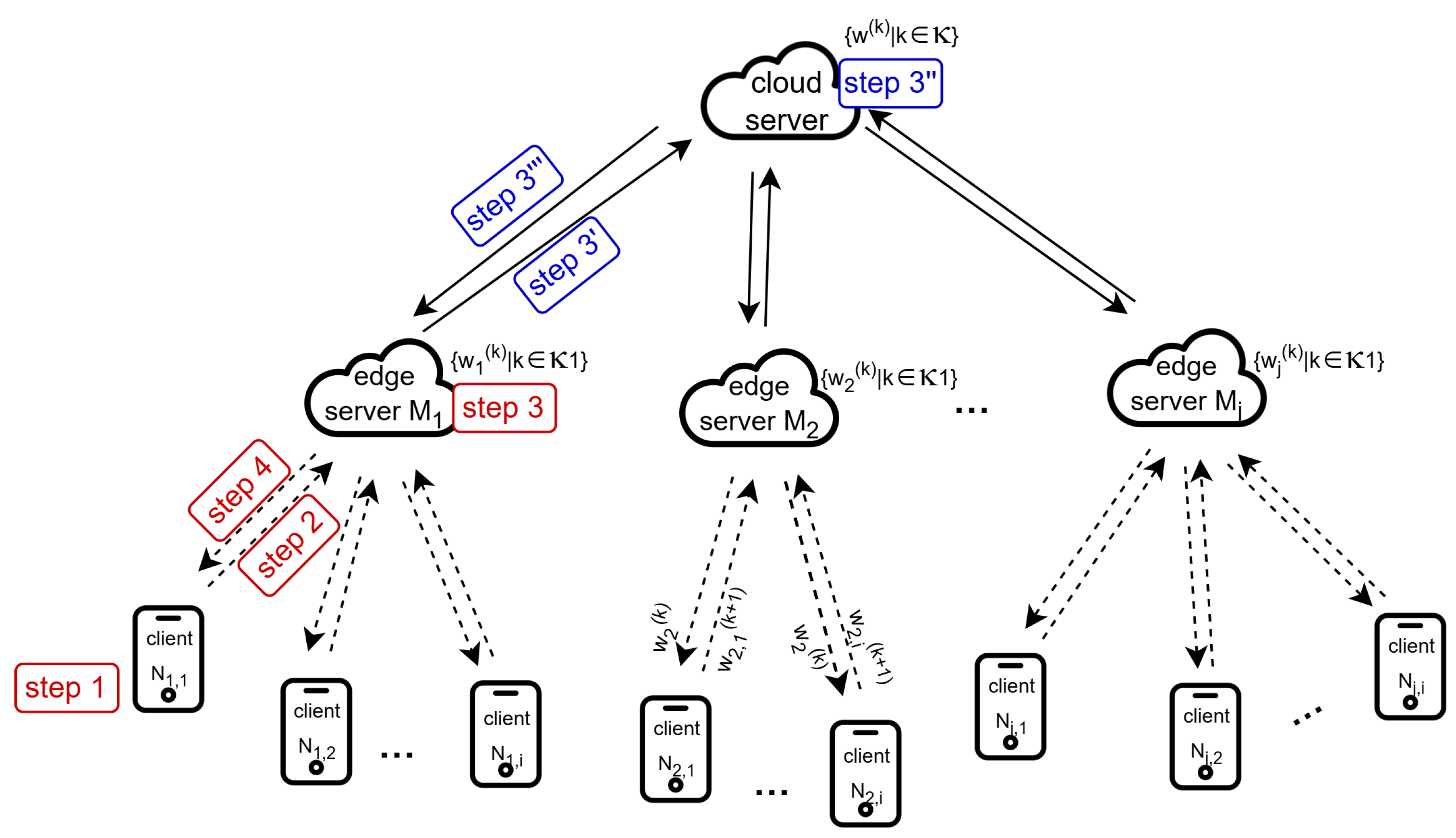

- To enable efficient large-model embedding training in IIoT, we adopt a client-edge-cloud hierarchical architecture that jointly considers limited network-computing resources. The system’s communication and computation performance is formulated as a constrained multi-objective optimization problem, which is decoupled into three levels: client-side feature learning, federated aggregation, and network-computing resource scheduling.

- We further customize a swarm intelligence-inspired Kepler Optimization Algorithm (KOA) to jointly optimize client-side model parameters, aggregation strategies, and network–computing scheduling strategy. The improved KOA incorporates a process-information storage table to significantly reduce repetitive computations and employs a priority-uniqueness mapping mechanism to preserve the uniqueness of priority assignments.

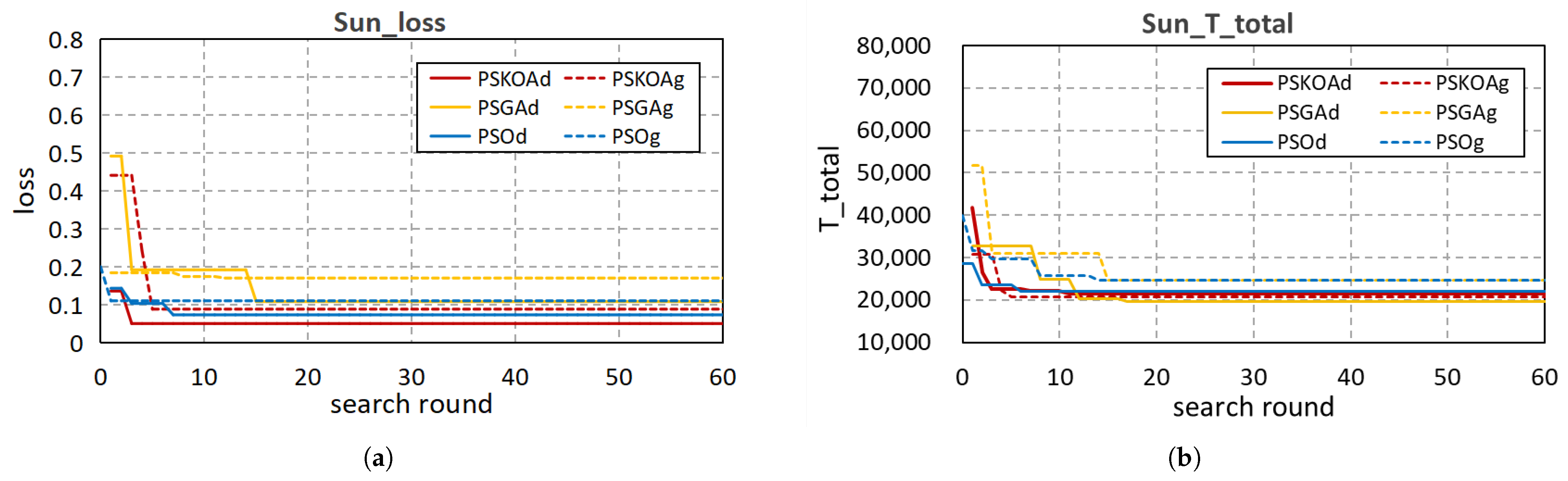

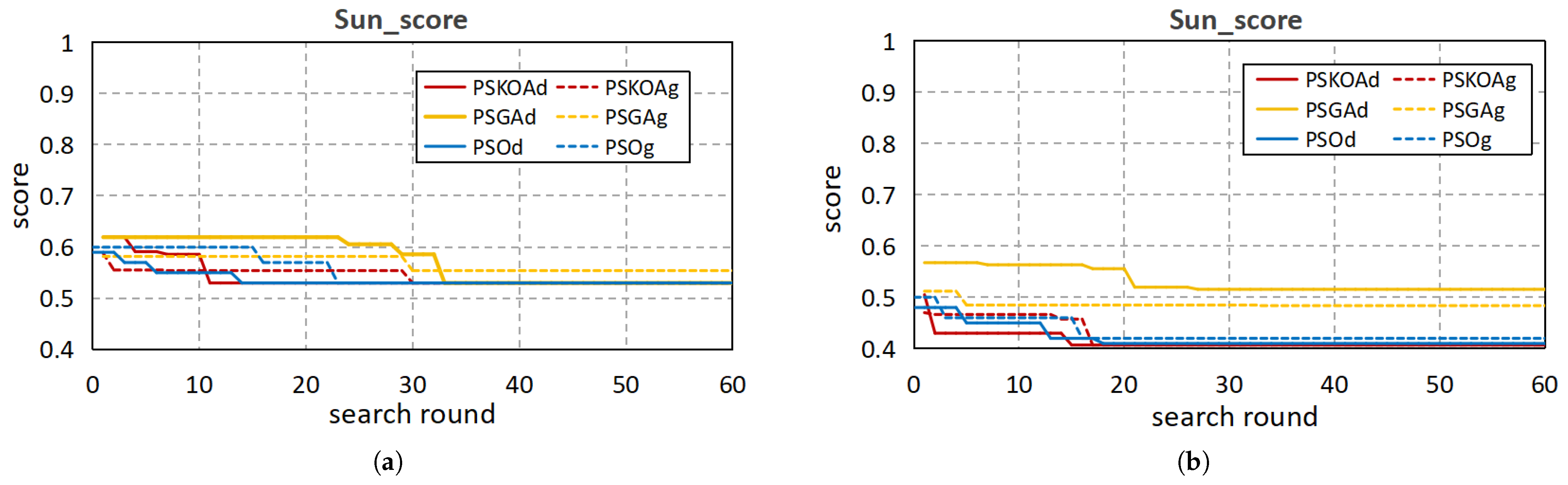

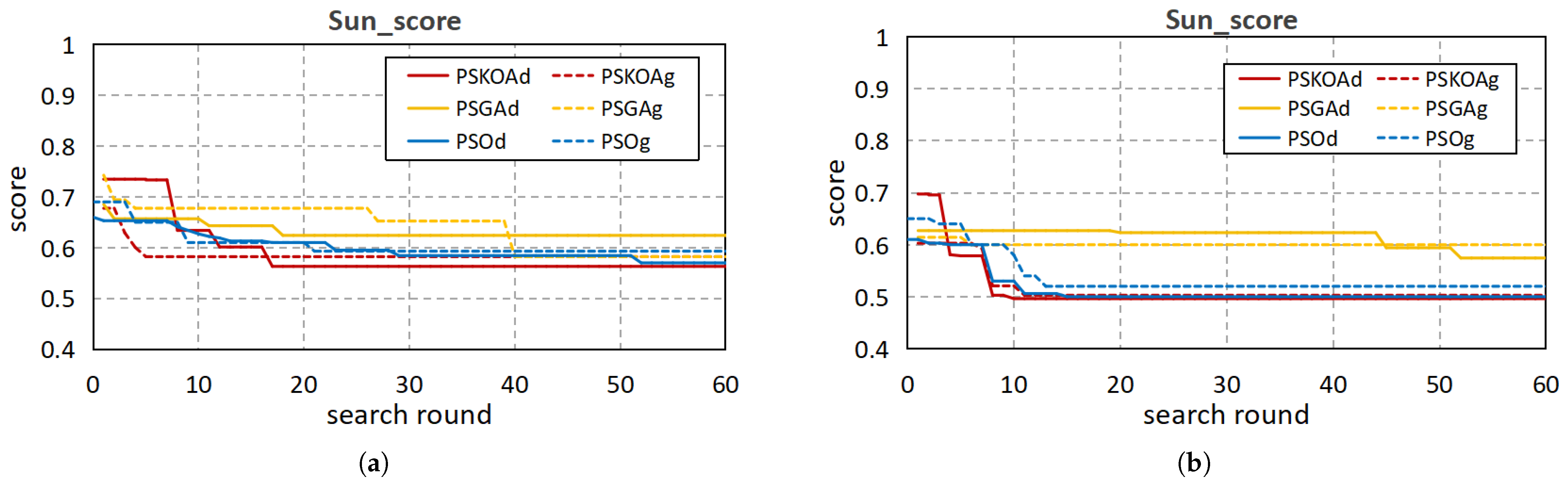

- Extensive evaluations demonstrate that the proposed method achieves lower model loss and shorter training time compared with existing approaches, validating its effectiveness in balancing training efficiency and model accuracy under constrained network–computing resources.

2. Related Work

2.1. IIoT and Large Models

2.2. Federated Learning in IIoT

3. System Model and Problem Statement

3.1. System Architecture

3.2. Problem Statement

4. Algorithm Design

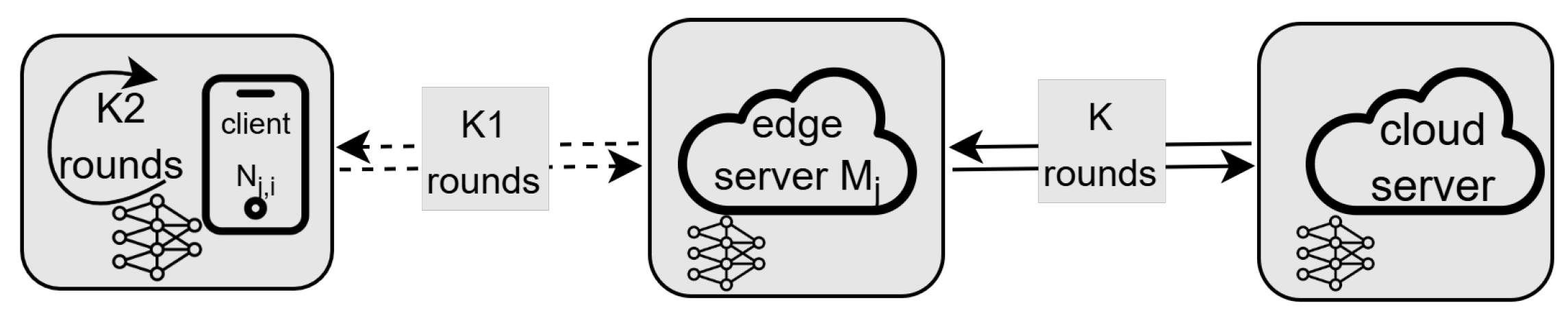

- : These parameters govern the federated learning process across the client-edge-cloud hierarchy. They control the number of local iterations and aggregation rounds, which are critical for balancing model performance with communication overhead.

- : This parameter governs the sequence of client-side parameter transmission. An optimal priority scheme mitigates bottlenecks under bandwidth constraints, thereby reducing the total training time and improving resource utilization.

- : This parameter defines the complexity of the feature learning model on each client. Optimizing enables resource-constrained clients to achieve accurate training while adhering to their computational limits.

4.1. Encoding and Decoding of Solutions

- (1)

- When traversing the vector, the first occurrence of a value is retained. Any subsequent duplicate is flagged for replacement.

- (2)

- Each duplicate entry is replaced by a value selected from the set of unused integers R. The replacement value is determined by:where r denotes the number of elements in the unused set R.

- (3)

- After replacement, the set R is updated by removing the assigned value, thereby maintaining the uniqueness of all entries in .

| Algorithm 1 Parameters Search based on KOA |

| Require: the number of planets , |

| the maximum search rounds , |

| the initialized position of any planet i |

| Ensure: the optimal solution Sun , |

| the best fitness value |

| 1: for each planet i |

| 2: |

| 3: |

| 4: while do |

| 5: for each do |

| 6: |

| 7: |

| 8: if then |

| 9: |

| 10: |

| 11: if then |

| 12: |

| 13: |

| 14: end if |

| 15: end if |

| 16: end for |

| 17: end while |

| 18: return |

4.2. Parameters Search

| Algorithm 2 Federated Learning Computing |

| Require: , M, , , K, , , |

| Ensure: Global model average loss |

| 1: for to K do |

| 2: Distribute global model to clients as initialized/updated local models |

| 3: for do |

| 4: for to do |

| 5: for do |

| 6: Client trains local model for iterations using local data |

| 7: end for |

| 8: Edge server aggregates parameters from connected clients |

| 9: Edge server redistributes updated parameters to clients |

| 10: end for |

| 11: end for |

| 12: Cloud server updates global model |

| 13: Calculate global model average loss |

| 14: end for |

| 15: return |

| Algorithm 3 Federated Learning Scheduling |

| Require: Scheduling strategy |

| Federated aggregation parameters K, , |

| Computation time: , , |

| Communication time between client and edge server: |

| Wireless communication maximum capacity Q |

| Maximum scheduling time |

| Ensure: Total model training time |

| 1: Initialize states of clients, edge servers, and cloud server |

| 2: |

| 3: while do |

| 4: for to K do |

| 5: Schedule clients based on and Q |

| 6: for to do |

| 7: Clients compute: local iterations taking time each iteration |

| 8: Clients communicate with edge servers: time |

| 9: Edge servers aggregate: time |

| 10: end for |

| 11: Cloud server aggregates: time |

| 12: end for |

| 13: |

| 14: if scheduling completes then |

| 15: break |

| 16: end if |

| 17: end while |

| 18: |

| 19: return |

5. Performance Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

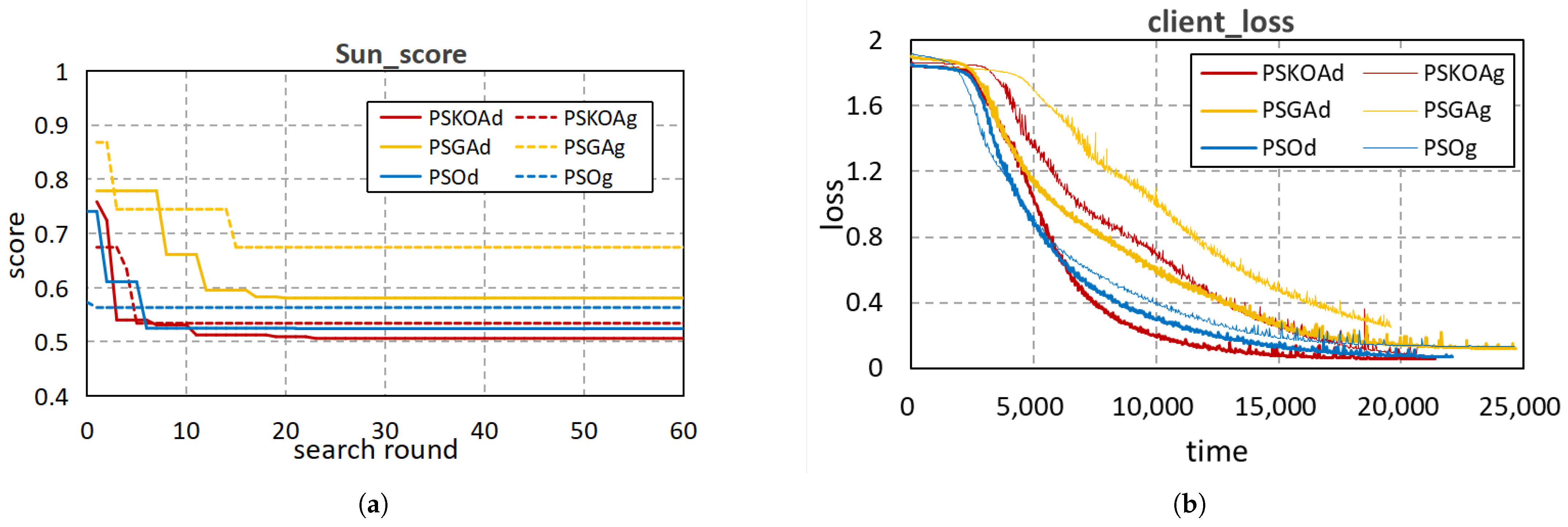

- Parameter search based on Kepler Optimization Algorithm (PSKOAd): This algorithm employs KOA to jointly optimize all parameters, including , , , and , explicitly balancing model accuracy and training time.

- Parameter search based on Kepler Optimization Algorithm with given Priority (PSKOAg): This variant uses KOA to optimize , , and under a fixed , disregarding communication scheduling.

- Parameter search based on Genetic Algorithm (PSGAd): GA is employed to optimize all parameters, including , , , and , balancing model accuracy and training time.

- Parameter search based on Genetic Algorithm with given Priority (PSGAg): GA optimizes , , and under a fixed scheduling .

- Parameter search based on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSOd): PSO is used to jointly optimize all parameters, including , , , and , balancing accuracy and training time.

- Parameter search based on Particle Swarm Optimization with given Priority (PSOg): PSO optimizes , , and under a fixed .

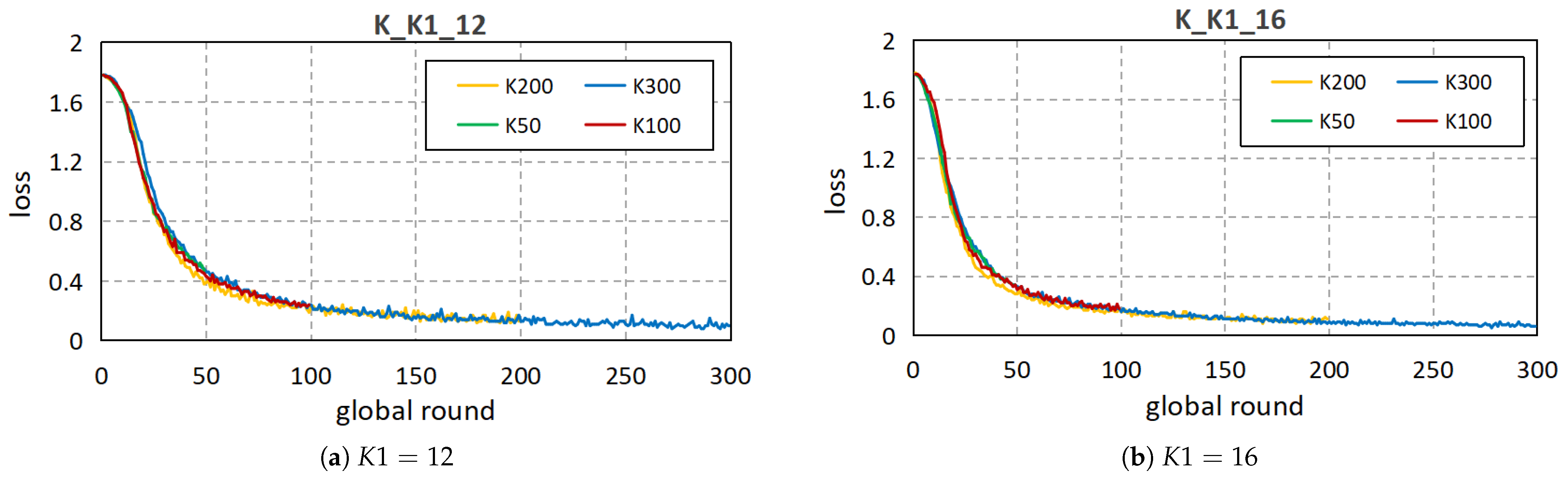

5.2. Simulation

5.2.1. Weighting of and

5.2.2. Parameter Search Scope

5.2.3. Communication Capacity

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| M | the set of edge servers |

| one edge server | |

| the client set connected with edge server | |

| one client connected with edge server | |

| Q | the system maximum capacity of wireless communication |

| the computing time in clients | |

| the computing time in edge servers | |

| the computing time in the cloud server | |

| the communication time between the client and the edge server | |

| the round of iterations performed by clients using local data | |

| the round of client-edge interaction within a global model update cycle | |

| K | the round of global model updating |

| the client model structure parameter | |

| the network-computing resource scheduling strategy | |

| the position of the Sun | |

| the position of any planet i |

References

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; et al. Flamingo: A visual language model for few-shot learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Mu, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, J.; Li, C.; Lee, Y.J. Gligen: Open-set grounded text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–23 June 2023; pp. 22511–22521. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chang, K.; Wu, Y. Multi-modal semantic understanding with contrastive cross-modal feature alignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.06355. [Google Scholar]

- Resende, C.; Folgado, D.; Oliveira, J.; Franco, B.; Moreira, W.; Oliveira, A., Jr.; Cavaleiro, A.; Carvalho, R. TIP4. 0: Industrial internet of things platform for predictive maintenance. Sensors 2021, 21, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.C.; Greenewald, K.; Lee, K.; Manso, G.F. The computational limits of deep learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.05558. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Nishio, T.; Yonetani, R. Client selection for federated learning with heterogeneous resources in mobile edge. In Proceedings of the ICC 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Shanghai, China, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Seneviratne, A.; Li, J.; Poor, H.V. Federated learning for internet of things: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1622–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanifi, O.R.A.; Chow, C.O.; Tham, M.L.; Chuah, J.H.; Kanesan, J. Communication and computation efficiency in federated learning: A survey. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Krishna, C.; Rajesh, R.; Ananthakrishnan, A.; Vishnuvardhan, A.; Patel, S.S.; Kapruan, C.; Brahmbhatt, S.; Kataray, T.; Narayanan, D.; et al. Industrial internet of things in intelligent manufacturing: A review, approaches, opportunities, open challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kundur, D.; Conti, M. Introduction to the special issue on integrity of multimedia and multimodal data in Internet of Things. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Rane, K.P.; Kakaravada, I.; Shabaz, M. Research on vibration monitoring and fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on internet of things technology. Nonlinear Eng. 2021, 10, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatov, N.; Paul, A.; Saeed, F.; Hong, W.H.; Seo, H.; Kim, J. Machine learning-based automated image processing for quality management in industrial Internet of Things. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2019, 15, 1550147719883551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.J.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A.; et al. Gpt-4o system card. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Su, X.; Tarkoma, S.; Jiang, T.; Crowcroft, J.; Hui, P. Edge intelligence: Empowering intelligence to the edge of network. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1778–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: A family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobalan, P.; Ramu, S.P.; Pham, Q.V.; Dev, K.; Pandya, S.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Huynh-The, T. Fusion of federated learning and industrial Internet of Things: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2022, 212, 109048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Husain, M.; Hans, P. Federated Learning-Enhanced Blockchain Framework for Privacy-Preserving Intrusion Detection in Industrial IoT. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.15376. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Tan, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Zeng, P.; Khan, M.; Das, S.K. Edge-computing-driven internet of things: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Jia, N.; Zhao, W. Federated learning-oriented edge computing framework for the IIoT. Sensors 2024, 24, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, P.; Boukerche, A.; et al. Edge-Cloud Collaborative Computing on Distributed Intelligence and Model Optimization: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.01821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Sun, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Fedmask: Joint computation and communication-efficient personalized federated learning via heterogeneous masking. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Coimbra, Portugal, 15–17 November 2021; pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Ullah, R.; Harvey, P.; Kilpatrick, P.; Spence, I.; Varghese, B. Fedadapt: Adaptive offloading for iot devices in federated learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 20889–20901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Poor, H.V.; Saad, W.; Cui, S. Convergence time optimization for federated learning over wireless networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 20, 2457–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Ye, W.; Tao, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Q. A survey of federated learning for edge computing: Research problems and solutions. High-Confid. Comput. 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J. Is the solar system stable? Hamilt. Dyn. Syst. Repr. Sel. 1987, 1, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gidlund, M. DeepHealth: A self-attention based method for instant intelligent predictive maintenance in industrial Internet of things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 5461–5473. Available online: https://github.com/Intelligent-AWE/DeepHealth (accessed on 7 October 2020). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, Y.; Jin, X.; Xia, C.; Xu, C.; Sun, Y. Communication-Computation Co-Optimized Federated Learning for Efficient Large-Model Embedding Training. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233871

Luo Y, Jin X, Xia C, Xu C, Sun Y. Communication-Computation Co-Optimized Federated Learning for Efficient Large-Model Embedding Training. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233871

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Yingying, Xi Jin, Changqing Xia, Chi Xu, and Yiming Sun. 2025. "Communication-Computation Co-Optimized Federated Learning for Efficient Large-Model Embedding Training" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233871

APA StyleLuo, Y., Jin, X., Xia, C., Xu, C., & Sun, Y. (2025). Communication-Computation Co-Optimized Federated Learning for Efficient Large-Model Embedding Training. Mathematics, 13(23), 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233871