A Novel Feature Representation and Clustering for Histogram-Valued Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review

2.1. Concept of Histogram-Valued Data

2.2. Clustering via Graph Learning

3. A Novel Feature Representation for Histogram-Valued Data

4. Proposed Clustering Method for Histogram-Valued Data Based on M-LARCQ Feature Representation

| Algorithm 1 Clustering for histogram-valued data based on M-LARCQ feature representation |

| Input: n samples described by p histogram-valued variables, , the number of clusters k Output: the similarity matrix , the weights and

|

5. Numerical Studies

5.1. Assessment Metrics

- (1)

- PurityPurity is defined as the proportion of samples whose obtained labels from the clustering results are consistent with the predetermined ones, which can be formulated aswhere is the set of those samples belonging to the m-th cluster in for , and is the set of those samples belonging to the q-th cluster in for .

- (2)

- Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)ARI is often used to measure the agreement between the obtained clustering results and the predetermined clusters, which is calculated bywhere is the number of samples belonging to both the cluster and the cluster , is the size of the cluster , and is the size of the cluster .

- (3)

- Normalized Mutual Information (NMI)Mutual information is a useful metric to measure the dependence between variables. Actually, the predetermined and predicted labels and can be regarded as the realization of two discrete random variables and on n histogram-valued observations. The possible values of can be while those of can be . Thus the mutual information of and , denoted as , is defined bywhere is the joint distribution of , and and represent the marginal distribution of and . To facilitate the convenience for comparison and explanation, some types of normalized mutual information (NMI) are introduced. Supposing and denote the entropy of and , respectively, that is, , , is generally defined by . Specifically, here is a function with respect to and . We adopt the arithmetic mean of and to normalize , which can be formulated by

5.2. Simulations on Synthetic Datasets

- ()

- Given the probability distribution , M single-valued observations are randomly generated from and denoted by .

- ()

- For the interval using the minimum and maximum of the M single-valued observations as the lower and upper bounds, H subintervals with equal lengths can be obtained. Then, the histogram is created by calculating the frequency of each subinterval.

- -

- Cluster 1: .

- -

- Cluster 2: .

- -

- Cluster 3: .

- -

- Cluster 1: , , , .

- -

- Cluster 2: , , , .

- -

- Cluster 3: , , , .

- -

- Cluster 1: , .

- -

- Cluster 2: .

- -

- Cluster 3: , .

- -

- Cluster 1: , , , , .

- -

- Cluster 2: , , , , .

- -

- Cluster 3: , , , , .

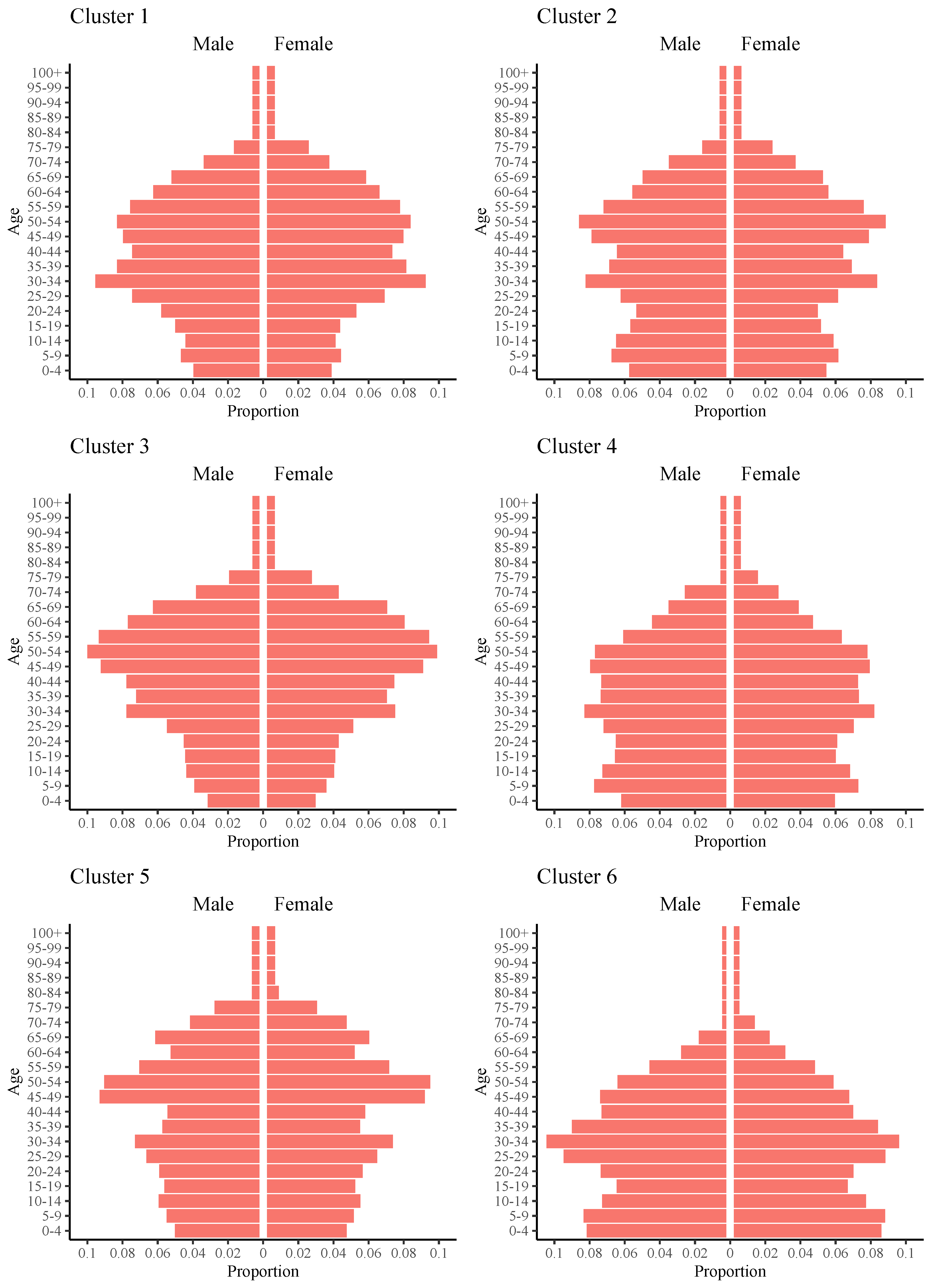

5.3. Application on Chinese Population Data

- Cluster 1 includes Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Hubei, and Inner Mongolia. For these 7 provinces, the proportion of male and female population under 14 years old is relatively low. According to the proportion data provided in https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/zk/indexce.htm (accessed on 15 June 2025), except Hubei and Jiangsu, the remaining provinces present super low birth rates. In addition, the proportion of the young and middle-aged population is relatively large, particularly the group aged 25-45 years old. This is consistent with the fact that most of these provinces are the main areas of labor force import in China. In addition, these provinces in this cluster have entered or will enter the stage of moderate aging.

- In Cluster 2, which includes Hebei, Shanxi, Anhui, Shandong, Hunan, Shanxi, and Gansu Provinces, the proportions of male and female juvenile population of the center are and , respectively, which are significantly higher than those of the center in Cluster 1, but are still in the stage of having fewer children. The proportions of young and middle-aged population for male and female are and , respectively, remarkably lower than those of the center of Cluster 1. As a matter of fact, for these provinces belonging to Cluster 2, exporting labors to other provinces is one of the important methods of transferring surplus labors. Considering the proportion of the elderly population, we observe that these provinces have entered the stage of moderate aging.

- Cluster 3 contains three northeastern provinces: Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning Provinces. As can be seen from Figure 4, the population pyramid of the center exhibits an inverted pyramid which is narrow at the bottom and wide at the top. Specifically, the proportions of juveniles in the male and female population are and , respectively, which are the smallest among the six clusters; thus, these three provinces present seriously low birth rates. The proportion of young and middle-aged population in Cluster 3 is similar to that in Cluster 1, but the middle and old population aged between 45 and 60 years old form the majority, and there is a serious loss of young labor force. It is noted that the proportions of male and female elderly population are and , respectively, which presents moderate aging of the society. On the whole, the three northeastern provinces will demonstrate a decreasing population in the future and face an increasingly serious aging problem.

- The provinces in Cluster 4 include Fujian, Jiangxi, Henan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang Provinces. We can observe that both the proportions of juveniles in the male and female population of the center are over , and, especially, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Henan Provinces present high birth rates and other provinces show normal birth rates. In addition, the proportion of the elderly population in this cluster is relatively low, presenting a mild aging trend. Concerning the young and middle-aged population, there is little difference in the proportion of groups at different ages. Overall, these provinces in this cluster tend to demonstrate the stationary population.

- Cluster 5 includes Chongqing and Sichuan. Compared with provinces of other clusters, the most distinguishing feature of these two provinces is the high proportions of the elderly population. Meanwhile, they are in the face of the problem of seriously low birth rates. Additionally, in the young and middle-aged population, the labor force being between 45 and 55 years old accounts for a relatively high proportion, while the younger population is relatively few. As a result, the population in Chongqing and Sichuan will be aging at a fast rate and there are not sufficient young people to replace and support the older generation.

- Cluster 6 contains only the Xizang Autonomous Region. It can be observed that, on the one hand, the proportions of the juvenile under 14 years old in male and female population are and , respectively, presenting a remarkably high birth rate. The main reasons lie in the historical background, Tibetan cultural traditions and government incentives. On the other hand, the proportion of the elderly population over 65 years old is lower than , presenting the smallest among all provinces, which may be influenced by the high proportions of the juvenile population. In addition, young and middle-aged people aged between 25 and 40 years old account for a relatively high proportion in Xizang, showing relatively rich labor force resources. Notably, the population structure of Xizang is most similar to the expansive pyramid among all provinces.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diday, E. The symbolic approach in clustering and related methods of data analysis. In Proceedings of the First Conference of the Federation of the Classification Societies, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 25–27 May 1988; pp. 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.; Brito, P. Linear regression model with histogram-valued variables. Stat. Anal. Data Mining ASA Data Sci. J. 2015, 8, 75–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.J.; Souza, R.M.; de Cysneiros, F.J. Psda: A tool for extracting knowledge from symbolic data with an application in brazilian educational data. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 1803–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagabhushan, P.; Pradeep Kumar, R. Histogram pca. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Neural Networks, Nanjing, China, 3–7 June 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1012–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.; Brito, P.; Amaral, P. Discriminant analysis of distributional data via fractional programming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Choi, H.; Delcher, C.; Wang, Y.; Yoon, Y.J. Convex clustering analysis for histogram-valued data. Biometrics 2019, 75, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Qin, Z. Principal component analysis for probabilistic symbolic data: A more generic and accurate algorithm. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 2015, 9, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, F.A.T.; de Souza, R.M. Unsupervised pattern recognition models for mixed feature-type symbolic data. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Dissimilarity Measures for Histogram-Valued Data and Divisive Clustering of Symbolic Objects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia Athens, Athens, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Billard, L. Dissimilarity measures for histogram-valued observations. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2013, 42, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irpino, A.; Verde, R. A new wasserstein based distance for the hierarchical clustering of histogram symbolic data. In Data Science and Classification; Batagelj, V., Bock, H.H., Ferligoj, A., Žiberna, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Billard, L. Dissimilarity measures and divisive clustering for symbolic multimodal-valued data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2012, 56, 2795–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irpino, A.; Verde, R.; Lechevallier, Y. Dynamic clustering of histograms using wasserstein metric. In Proceedings of the COMPSTAT 2006—Advances in Computational Statistics, Rome, Italy, 28 August–1 September 2006; Citeseer: State College, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Terada, Y.; Yadohisa, H. Non-hierarchical clustering for distribution-valued data. In Proceedings of the COMPSTAT, Paris, France, 22–27 August 2010; pp. 1653–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Deng, Q.; Huang, D.; Jing, B.; Zhang, B. Clustering based on kolmogorov–smirnov statistic with application to bank card transaction data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C 2021, 70, 558–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diday, E.; Govaert, G. Classification automatique avec distances adaptatives. Rairo Informatque Comput. Sci. 1977, 11, 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Irpino, A.; Verde, R.; de Carvalho, F.T. Dynamic clustering of histogram data based on adaptive squared wasserstein distances. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 3351–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irpino, A.; Verde, R.; de Carvalho, F.T. Fuzzy clustering of distributional data with automatic weighting of variable components. Inf. Sci. 2017, 406, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, F.A.T.; Irpino, A.; Verde, R.; Balzanella, A. Batch self-organizing maps for distributional data with an automatic weighting of variables and components. J. Classif. 2022, 39, 343–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, F.A.T.; Balzanella, A.; Irpino, A.; Verde, R. Co-clustering algorithms for distributional data with automated variable weighting. Inf. Sci. 2021, 549, 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavent, M. Criterion-based divisive clustering for symbolic data. In Analysis of Symbolic Data: Exploratory Methods for Extracting Statistical Information from Complex Data; Bock, H.H., Diday, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Billard, L. Clustering interval-valued data using principal components. J. Stat. Theory Pract. 2025, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá, J.N.A.; Ferreira, M.R.P.; de Carvalho, F.A.T. Kernel clustering with automatic variable weighting for interval data. Neurocomputing 2025, 650, 130849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.; De Giovanni, L.; Alaimo, L.S.; Mattera, R.; Vitale, V. Fuzzy clustering with entropy regularization for interval-valued data with an application to scientific journal citations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 342, 1605–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Liu, Z.; Letchmunan, S. INCM: Neutrosophic c-means clustering algorithm for interval-valued data. Granul. Comput. 2024, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Jeng, J.-T. Interval Generalized Improved Fuzzy Partitions Fuzzy C-Means Under Hausdorff Distance Clustering Algorithm. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 27, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Jordan, M.; Weiss, Y. On spectral clustering: Analysis and an algorithm. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2001, 14, 849–856. [Google Scholar]

- Billard, L.; Diday, E. Symbolic Data Analysis: Conceptual Statistics and Data Mining; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Leahy, R. An optimal graph theoretic approach to data clustering: Theory and its application to image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1993, 15, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, L.; Kahng, A.B. New spectral methods for ratio cut partitioning and clustering. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 1992, 11, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Malik, J. Normalized cuts and image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 888–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Wang, X.; Jordan, M.; Huang, H. The constrained laplacian rank algorithm for graph-based clustering. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, F.R.K. Spectral Graph Theory; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mohar, B.; Alavi, Y.; Chartrand, G.; Oellermann, O. The laplacian spectrum of graphs. Graph Theory Comb. Appl. 1991, 2, 871–898. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, F.; Li, J.; Li, X. Self-weighted multiview clustering with multiple graphs. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; pp. 2564–2570. [Google Scholar]

- Ichino, M. Symbolic pca for histogram-valued data. In Proceedings of the IASC2008, Yokohama, Japan, 16–18 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Verde, R.; Irpino, A. Multiple factor analysis of distributional data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, R.; Irpino, A.; Balzanella, A. Dimension reduction techniques for distributional symbolic data. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2015, 46, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, K. On a theorem of weyl concerning eigenvalues of linear transformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1949, 35, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Nie, F.; Huang, H. A new simplex sparse learning model to measure data similarity for clustering. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Case I-1 | Case I-2 | Case I-3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMI | ARI | Purity | NMI | ARI | Purity | NMI | ARI | Purity | |

| GC-ML | |||||||||

| Kmeans-ML | |||||||||

| SC-ML | |||||||||

| STANDARD | |||||||||

| GC-AWD | |||||||||

| CDC-AWD | |||||||||

| FCM | |||||||||

| AFCM-a | |||||||||

| AFCM-b | |||||||||

| AFCM-c | |||||||||

| AFCM-d | |||||||||

| AFCM-e | |||||||||

| AFCM-f | |||||||||

| BSOM | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-1 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-2 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-3 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-4 | |||||||||

| Method | Case II-1 | Case II-2 | Case II-3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMI | ARI | Purity | NMI | ARI | Purity | NMI | ARI | Purity | |

| GC-ML | |||||||||

| Kmeans-ML | |||||||||

| SC-ML | |||||||||

| STANDARD | |||||||||

| GC-AWD | |||||||||

| CDC-AWD | |||||||||

| FCM | |||||||||

| AFCM-a | |||||||||

| AFCM-b | |||||||||

| AFCM-c | |||||||||

| AFCM-d | |||||||||

| AFCM-e | |||||||||

| AFCM-f | |||||||||

| BSOM | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-1 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-2 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-3 | |||||||||

| ADBSOM-4 | |||||||||

| Case I-1 | Case I-2 | Case I-3 | Case II-1 | Case II-2 | Case II-3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | Provinces |

|---|---|

| 1 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Hubei, Neimenggu |

| 2 | Hebei, Shanxi, Anhui, Shandong, Hunan, Shanxi, Gansu |

| 3 | Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning |

| 4 | Fujian, Jiangxi, Henan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Qinghai |

| Ningxia, Xinjiang | |

| 5 | Chongqing, Sichuan |

| 6 | Xizang |

| Cluster | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 14 | 15–64 | Over 65 | Under 14 | 15–64 | Over 65 | |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| 6 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Q.; Wang, H. A Novel Feature Representation and Clustering for Histogram-Valued Data. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233840

Zhao Q, Wang H. A Novel Feature Representation and Clustering for Histogram-Valued Data. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233840

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Qing, and Huiwen Wang. 2025. "A Novel Feature Representation and Clustering for Histogram-Valued Data" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233840

APA StyleZhao, Q., & Wang, H. (2025). A Novel Feature Representation and Clustering for Histogram-Valued Data. Mathematics, 13(23), 3840. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233840