Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Control Based on sEMG-Driven Model Through Adaptive Fuzzy Inference

Abstract

1. Introduction

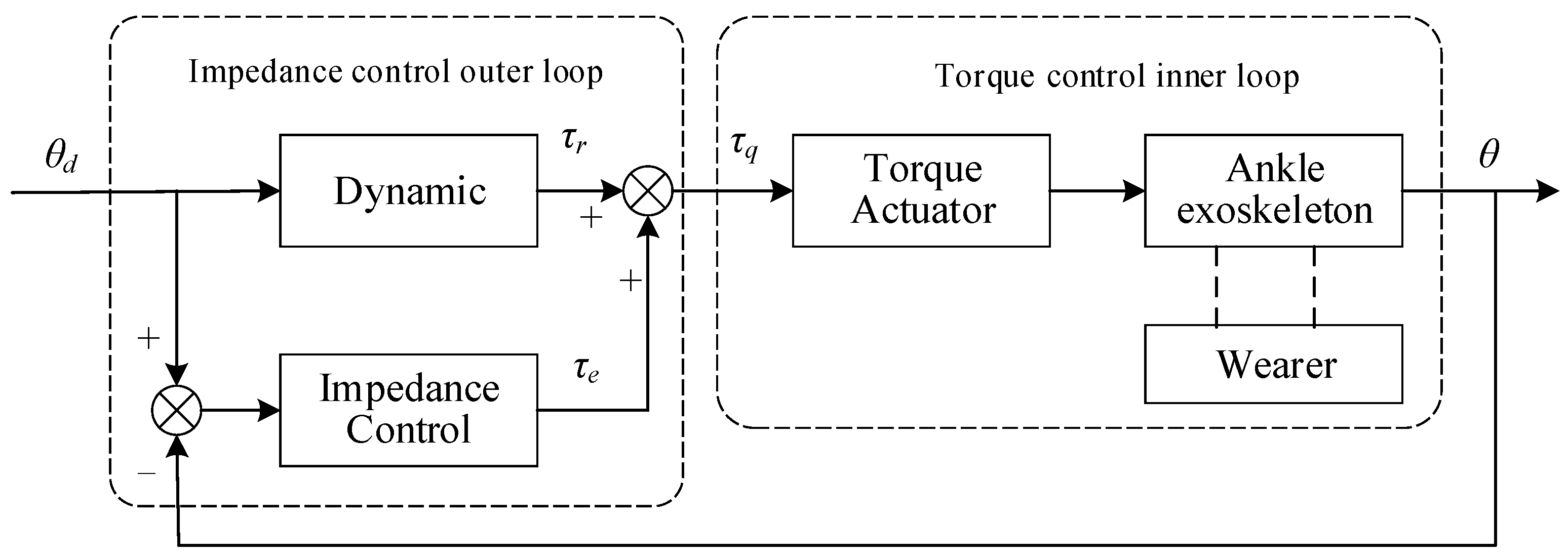

2. Proposed Adaptive Impedance Control

2.1. Control Method Overview

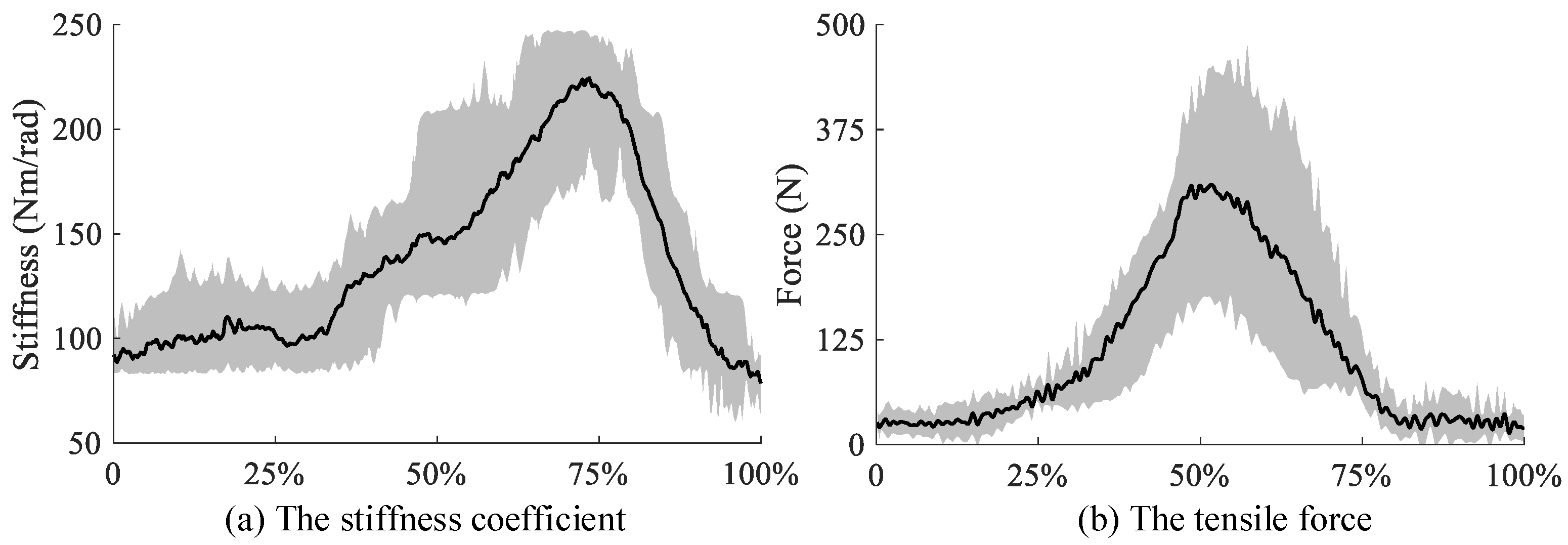

2.2. Impedance Control Model

2.3. sEMG Acquisition and Processing

| Algorithm 1 sEMG Processing |

|

- Step 1:

- A fourth-order Butterworth band-stop filter (49∼51 Hz) was implemented to eliminate 50 Hz powerline interference, utilizing bidirectional (forward-backward) filtering to achieve zero-phase distortion, with a measured group delay of 80 ms.

- Step 2:

- Fourth-order Butterworth filter with the frequency of 10 Hz is used to filter the absolute value of the signal to eliminate low-frequency interference, while preserving key muscle activation features.

- Step 3:

- Using fourth-order Butterworth filter with the frequency of 3 Hz, low-pass filtering the signal after high-pass filtering to obtain the envelope of sEMG. Similarly, the signal is processed by forward and backward bidirectional low-pass filtering.

- Step 4:

- sEMG normalization was performed using MVC measured for each participant to account for inter-subject variability in muscle size and signal gain, and to make the sEMG signal value range 0∼1.

- Step 5:

- The sEMG signal is transformed into the muscle stimulation signal by using the second-order difference equation, which can be expressed as:where d represents delay of sEMG signal, , , are the paraments of the second-order difference equation. In this work, the parameter values d = 10 ms , , were derived from electromechanical delay measurements and stability constraints of the difference equation. In addition, the muscle stimulation signal is transformed into muscle activation by nonlinear processing. This process is expressed as:where A is a nonlinear processing factor with a value range of −3 to 0, in this work .

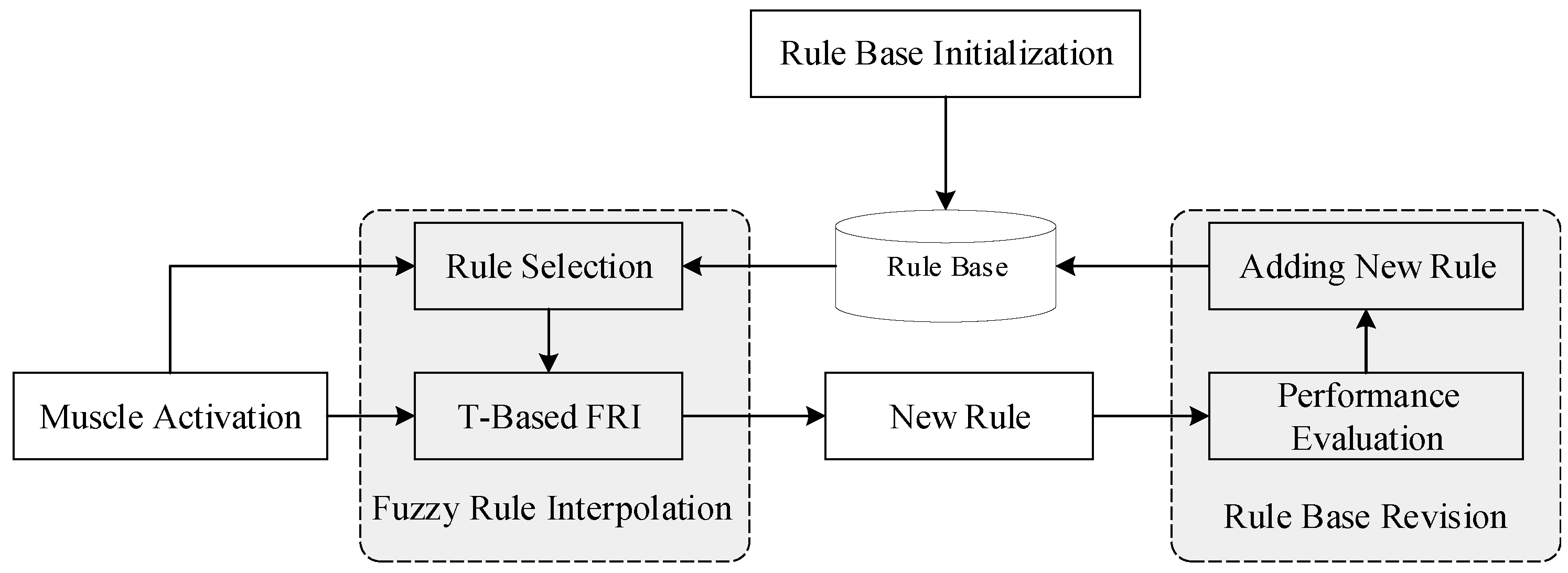

2.4. Experience-Based Fuzzy Rule Inference

2.4.1. Rule Base Initialization

2.4.2. Fuzzy Rule Interpolation

2.4.3. Rule Base Revision

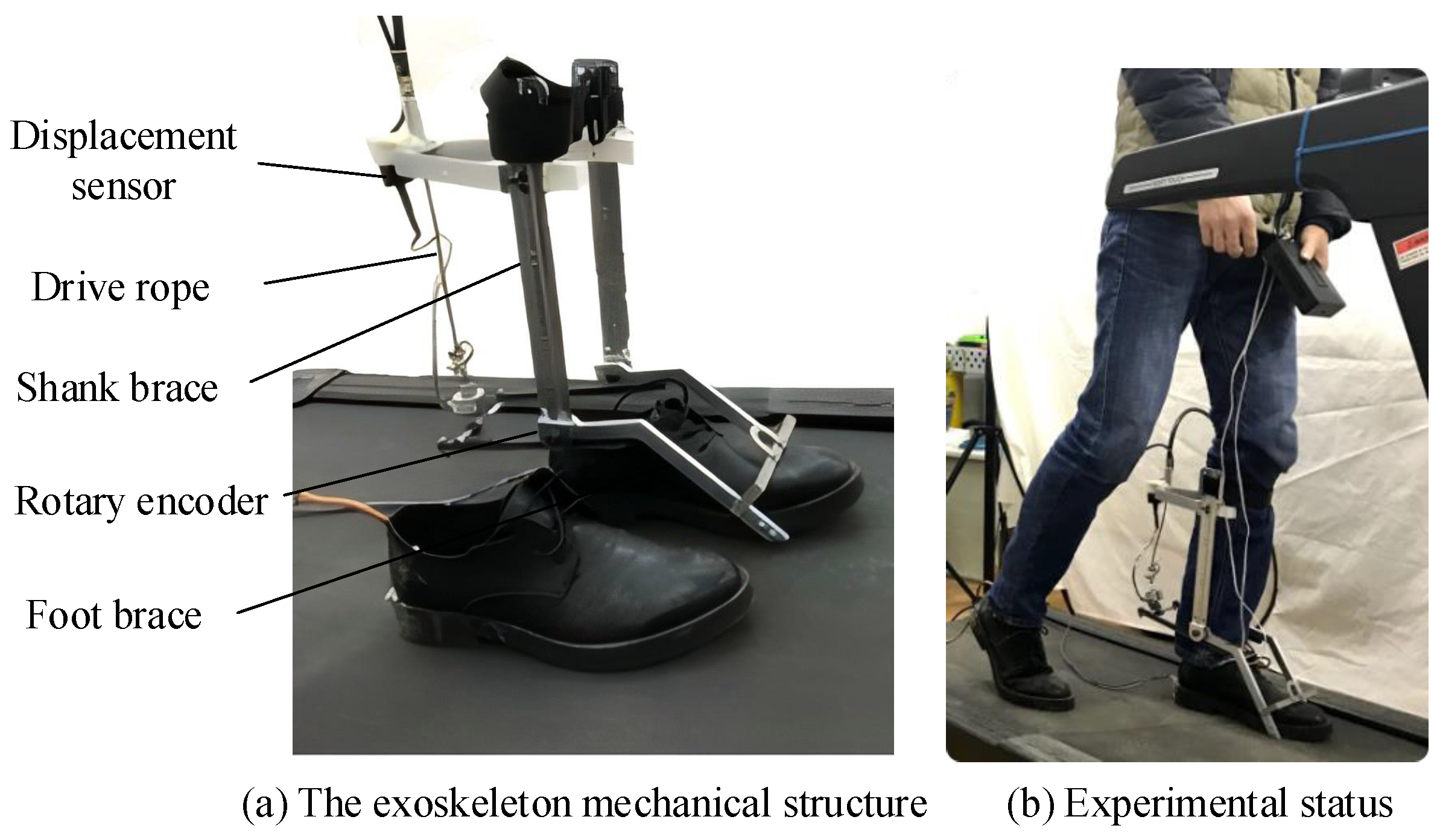

3. Experimentation

3.1. Experiment Condition

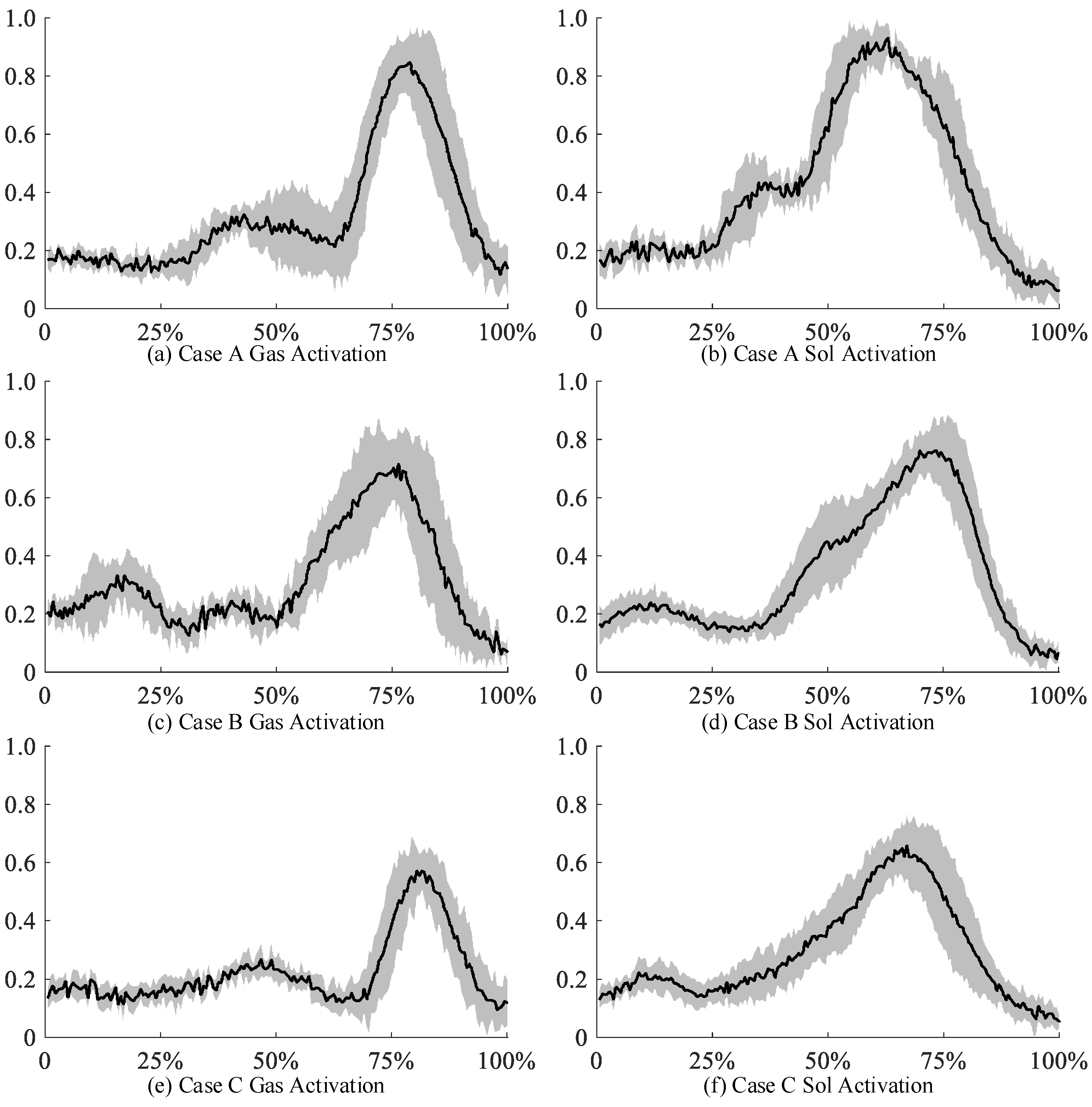

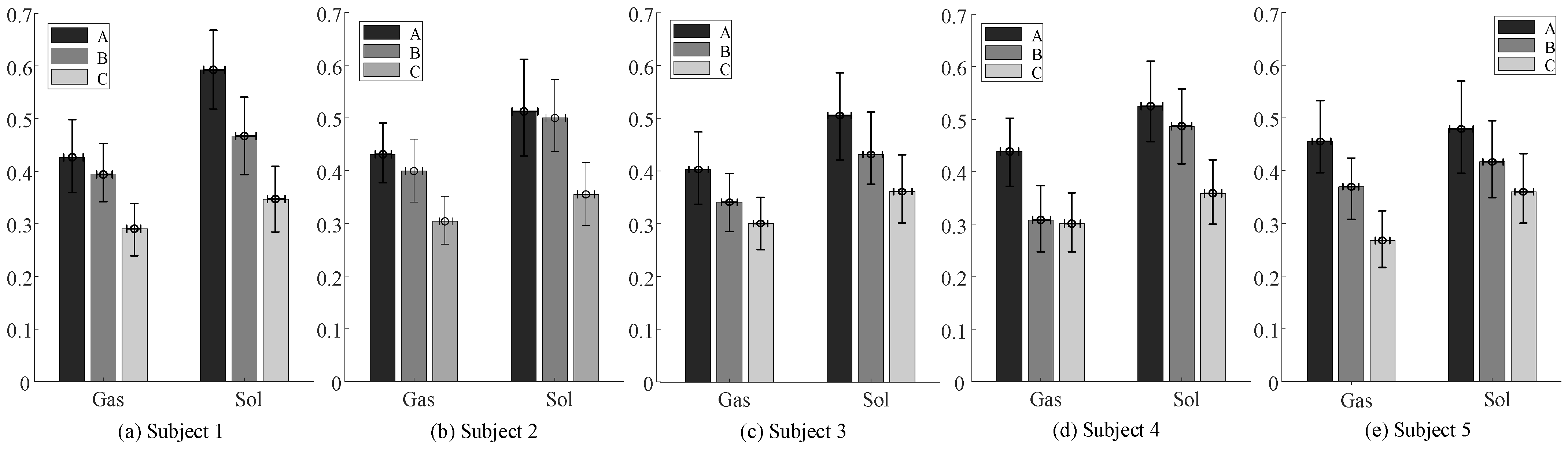

- Case A:

- The ankle exoskeleton remains unactuated. This experimental setup aims to examine the impact of wearing an exoskeleton on the calf muscle activation of the subjects during exercise. Here, the subject dons the unactuated ankle exoskeleton.

- Case B:

- The ankle exoskeleton is regulated by the traditional impedance control approach. In the traditional impedance control method, throughout the control process, the impedance parameters do not vary according to the different interaction states between the wearer and the exoskeleton. The stiffness N·m/rad was derived from biomechanical studies on healthy ankle dynamics [26]. The damping N·m·s/rad obtained by Equation (11). And the inertia kg·m2/rad reflected the exoskeleton-human system average inertial property. The desired assistance torque can be computed using Equation (5).

- Case C:

- The proposed adaptive impedance control strategy was implemented on the ankle exoskeleton. In this experiment, five healthy participants were recruited. Their average age was years, average height was m, and average weight was kg (presented as mean ± standard deviation). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pingdingshan University. Before participating, all individuals provided documented consent, and all the collected data were anonymized. Drawing on the research findings regarding the relationship between human ankle muscle activation and ankle stiffness, three fuzzy rules were initialized, as shown in Table 1. In this study, the similarity degree threshold was set at 0.7. Subsequently, the inherent weight of each rule was calculated using Equation (9), with parameter values of , , and .

3.2. Experiment Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erdogan, A.; Celebi, B.; Satici, A.C.; Patoglu, V. Assiston-ankle: A reconfigurable ankle exoskeleton with series-elastic actuation. Auton. Robot. 2017, 41, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Li, J.; Dong, M.; Zhou, X.; Fan, W.; Kong, Y. Design and performance evaluation of a novel wearable parallel mechanism for ankle rehabilitation. Front. Neurorobot. 2020, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhetenbayev, N.; Balbayev, G.; Zhauyt, A.; Shingissov, B. Design and performance of the new ankle joint exoskeleton. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res. 2023, 12, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fiers, P.; Witte, K.A.; Jackson, R.W.; Poggensee, K.L.; Atkeson, C.G.; Collins, S.H. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance during walking. Science 2017, 356, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Xiang, K.; Pang, M.; Chen, J.; Anderson, P.; Yang, L. Personalised control of robotic ankle exoskeleton through experience-based adaptive fuzzy inference. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 72221–72233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zeng, C.; Liang, P.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Su, C.-Y. Interface design of a physical human–robot interaction system for human impedance adaptive skill transfer. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2017, 15, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Dong, D.; Chen, X.; Bai, L. From sensing to control of lower limb exoskeleton: A systematic review. Annu. Control 2022, 53, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Ning, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, W.; Wu, X.; Chen, C. A novel motion intention recognition approach for soft exoskeleton via imu. Electronics 2020, 9, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Chen, J.; Xiang, K.; Pang, M.; Tang, B.; Li, J.; Yang, L. Artificial human balance control by calf muscle activation modelling. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 86732–86744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaccio, S.; Viscuso, S. An emg-controlled sma device for the rehabilitation of the ankle joint in post-acute stroke. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Tong, K.-y.; Hu, X.; Zhou, W. Myoelectrically controlled wrist robot for stroke rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, J.R.; Jacobs, D.A.; Ferris, D.P.; Remy, C.D. Learning to walk with an adaptive gain proportional myoelectric controller for a robotic ankle exoskeleton. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, X. An semg based adaptive method for human-exoskeleton collaboration in variable walking environments. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 74, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, D.D.; Kang, I.; Young, A.J. Estimating human joint moments unifies exoskeleton control, reducing user effort. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadi8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüktabak, E.B.; Wen, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Short, M.R.; Ludvig, D.; Hargrove, L.; Perreault, E.J.; Lynch, K.M.; Pons, J.L. Haptic transparency and interaction force control for a lower limb exoskeleton. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 1842–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X. A tutorial survey and comparison of impedance control on robotic manipulation. Robotica 2019, 37, 801–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglia, J.A.; Tsagarakis, N.G.; Dai, J.S.; Caldwell, D.G. Control strategies for patient-assisted training using the ankle rehabilitation robot (arbot). IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2012, 18, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, B.; van Asseldonk, E.H.; van der Kooij, H. Speed-dependent reference joint trajectory generation for robotic gait support. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Peng, Z.; Hu, J.; Ghosh, B.K. Event-triggered critic learning impedance control of lower limb exoskeleton robots in interactive environments. Neurocomputing 2024, 564, 126963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Jin, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Neural learning impedance control of lower limb rehabilitation exoskeleton with flexible joints in the presence of input constraints. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2023, 33, 4191–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari, M.; Haghjoo, M.R.; Taghizadeh, M. Model-free adaptive variable impedance control of gait rehabilitation exoskeleton. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Dai, K.; Xue, Y.; Yang, L. Adaptive ankle impedance control for bipedal robotic upright balance. Expert Syst. 2023, 40, e13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, C.G.; Voloshina, A.S.; Chiu, V.L.; Collins, S.H. Shortcomings of human-in-the-loop optimization of an ankle-foot prosthesis emulator: A case series. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 202020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Huang, P.; Xia, H.; Li, G. Human-in-the-loop adaptive control of a soft exo-suit with actuator dynamics and ankle impedance adaptation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 7920–7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chao, F.; Shen, Q. Generalized adaptive fuzzy rule interpolation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 25, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Jin, Y.; Du, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, P.; Ma, Z. Virtual neuromuscular control for robotic ankle exoskeleton standing balance. Machines 2022, 10, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shang, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, Q. Approximate reasoning with fuzzy rule interpolation: Background and recent advances. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 4543–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shum, H.P.; Fu, X.; Sexton, G.; Yang, L. Experience-based rule base generation and adaptation for fuzzy interpolation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 102–109. [Google Scholar]

| i | A1i | A2i | Bi | wi | EFi | CDi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (0.5, 0.45, 0.4) | (0.7, 0.6, 0.5) | (150.0, 145.0, 100.0) | 0.099 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | (0.4, 0.3, 0.2) | (0.5, 0.4, 0.3) | (100.0, 75.0, 50.0) | 0.099 | 100 | 0 |

| 3 | (0.2, 0.1, 0.0) | (0.3, 0.2, 0.0) | (50.0, 25.0, 10.0) | 0.099 | 100 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Li, W.; Yin, K.; Xue, Y.; Chen, Y. Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Control Based on sEMG-Driven Model Through Adaptive Fuzzy Inference. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233839

Zhao H, Li W, Yin K, Xue Y, Chen Y. Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Control Based on sEMG-Driven Model Through Adaptive Fuzzy Inference. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233839

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Huanli, Weiqiang Li, Kaiyang Yin, Yaxu Xue, and Yi Chen. 2025. "Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Control Based on sEMG-Driven Model Through Adaptive Fuzzy Inference" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233839

APA StyleZhao, H., Li, W., Yin, K., Xue, Y., & Chen, Y. (2025). Powered Ankle Exoskeleton Control Based on sEMG-Driven Model Through Adaptive Fuzzy Inference. Mathematics, 13(23), 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233839