A Link Prediction Algorithm Based on Layer Attention Mechanism for Multiplex Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Link Prediction Methods for Single-Layer Networks

2.2. Link Prediction Methods for Multiplex Networks

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Description of Link Prediction for Multiplex Networks

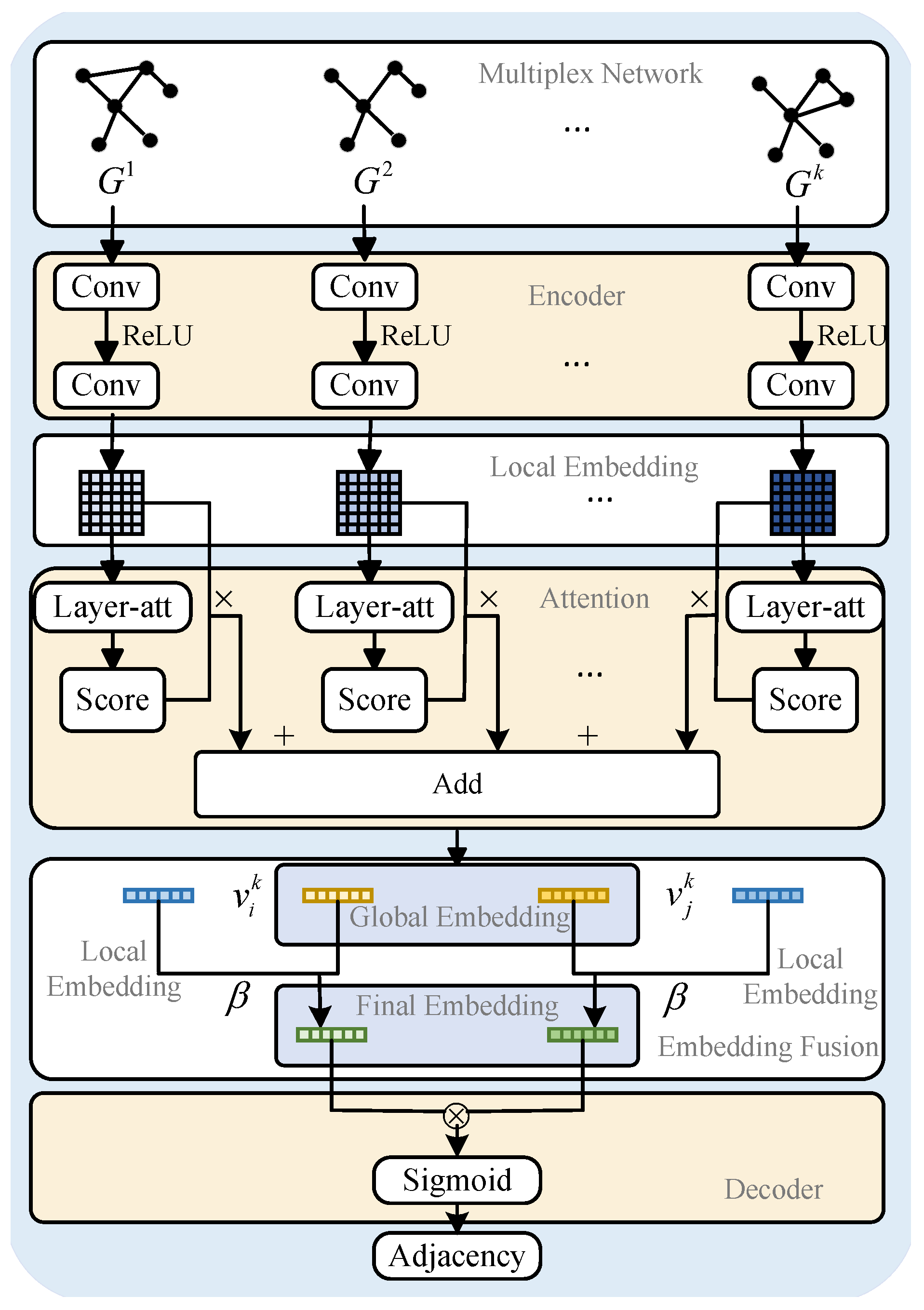

3.2. The Proposed Model

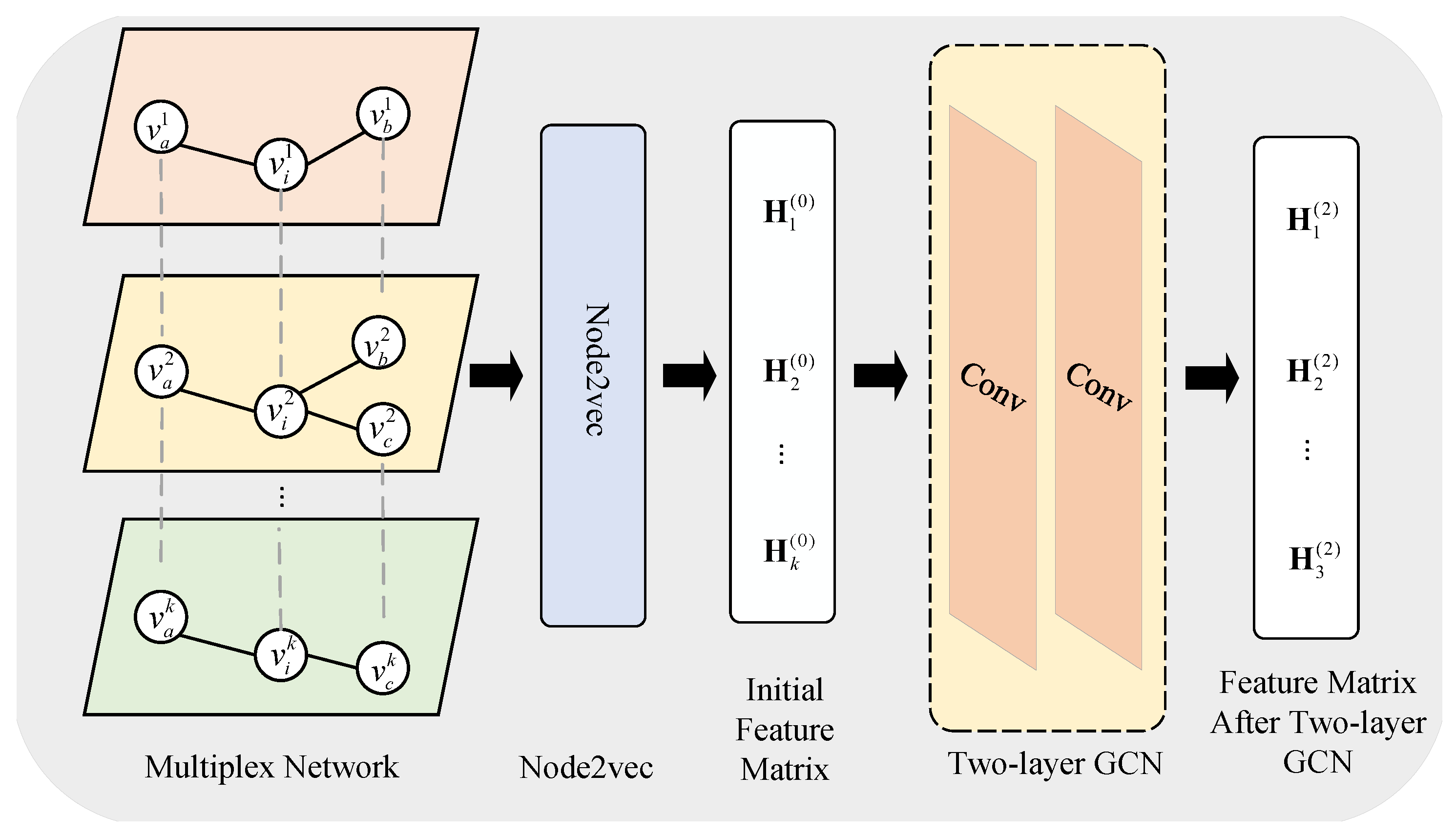

3.2.1. Embedding Representation Extraction Module

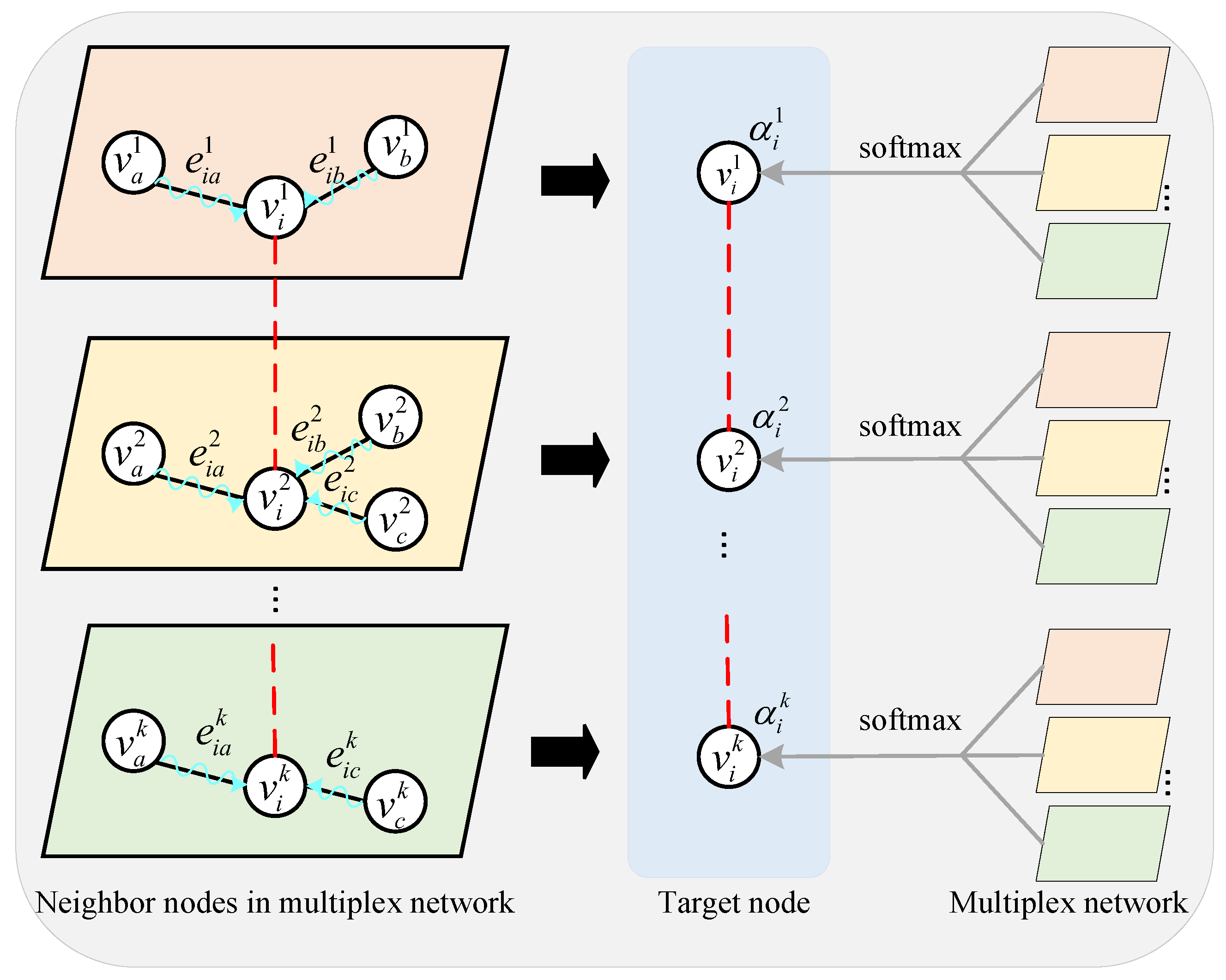

3.2.2. Layer Attention Mechanism Module

3.2.3. Embedding Representation Fusion Module

3.2.4. Model Optimization

3.3. Complexity Analysis

4. Experiment

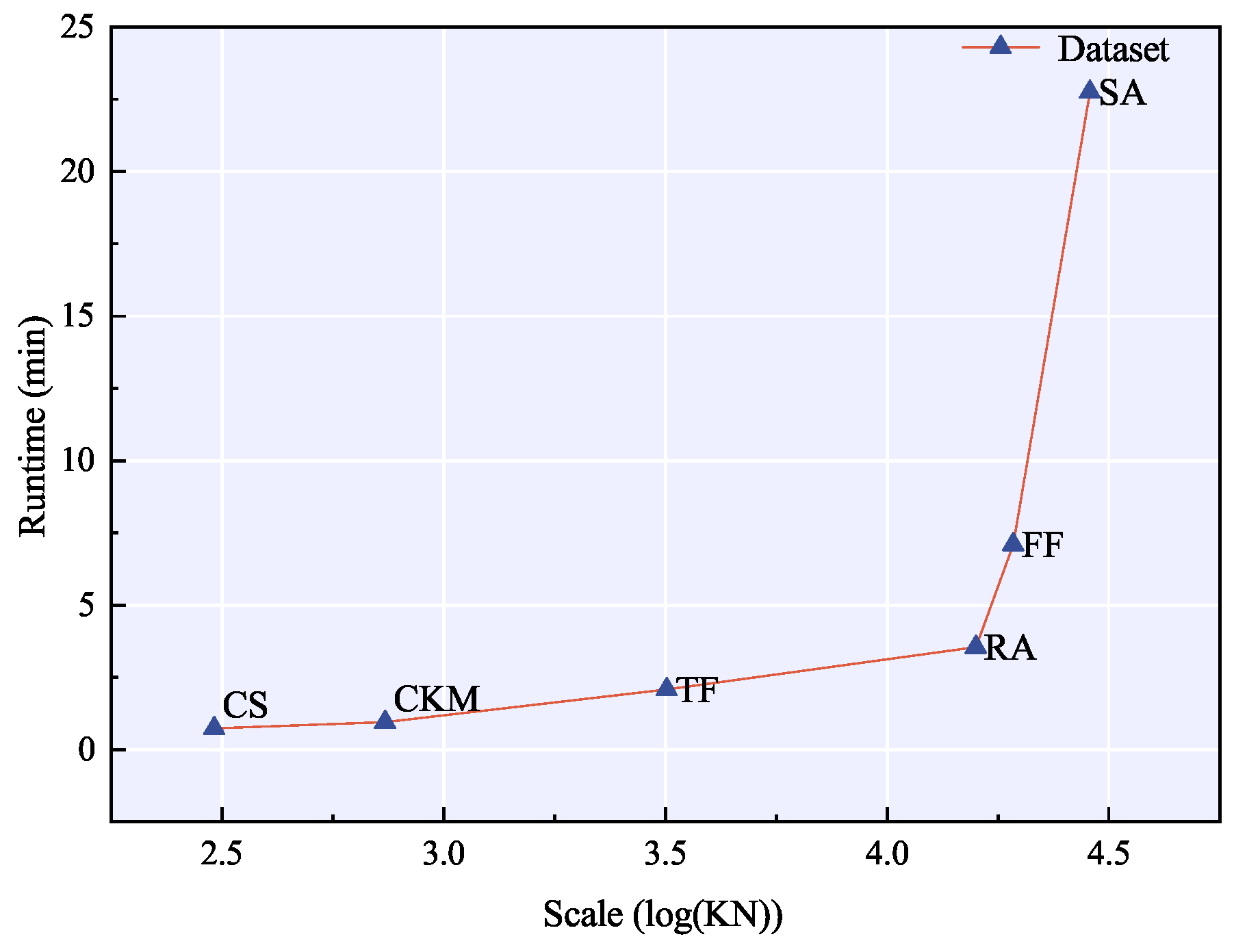

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Experimental Settings

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Baseline Methods

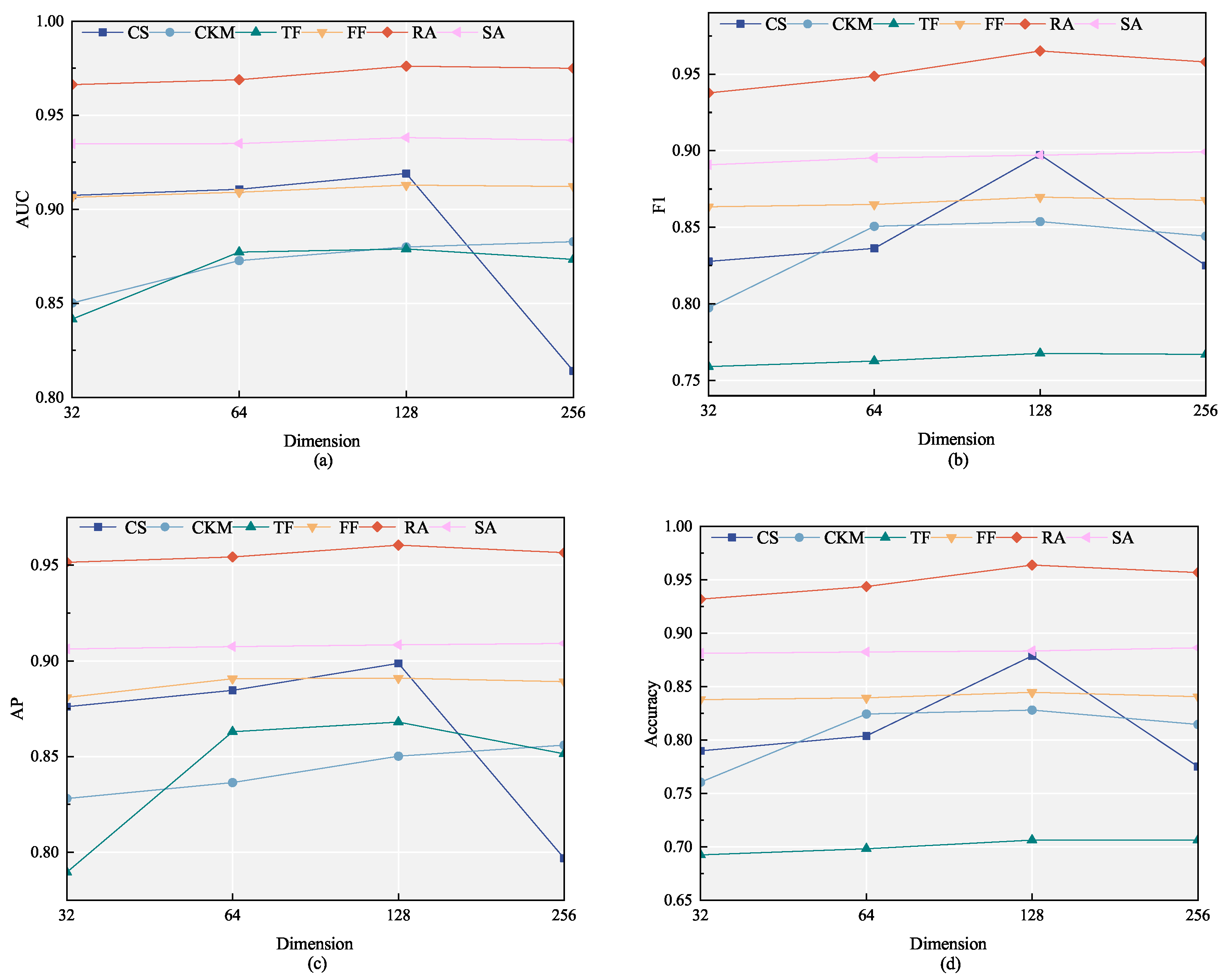

4.5. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

4.6. Comparison of the Link Prediction Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, M.; Wang, D. An Attribute Graph Embedding Algorithm for Sensing Topological and Attribute Influence. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Y.; Yuan, W.; Ma, L.; Yu, K. A Survey on Exploring Real and Virtual Social Network Rumors: State-of-the-Art and Research Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, L.; Fang, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Yu, K.; Zhang, J. Multistage competitive opinion maximization with Q-learning-based method in social networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 7158–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, T.J.; Bhavani, S.D. Link prediction approach to recommender systems. Computing 2024, 106, 2157–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljabbar, D.A.; Hashim, S.Z.M.; Sallehuddin, R. An enhanced evolutionary algorithm for detecting complexes in protein interaction networks with heuristic biological operator. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances on Soft Computing and Data Mining: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Soft Computing and Data Mining (SCDM 2020), Melaka, Malaysia, 22–23 January 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 334–345. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, X.; Yang, L. Hierarchical traffic flow prediction based on spatial-temporal graph convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16137–16147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, P.; Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najari, S.; Salehi, M.; Ranjbar, V.; Jalili, M. Link prediction in multiplex networks based on interlayer similarity. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 536, 120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Jiao, P.; Lu, R.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Inductive link prediction via interactive learning across relations in multiplex networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2022, 11, 3118–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Jiao, P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, X. Layer information similarity concerned network embedding. Complexity 2021, 2021, 2260488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. Clustering and preferential attachment in growing networks. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 025102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierk, S. The SMART retrieval system: Experiments in automatic document processing—Gerard Salton, Ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1971, 556 pp., $15.00). IEEE Trans. Prof. Commun. 1972, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, T. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biol. Skr. 1948, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ravasz, E.; Somera, A.L.; Mongru, D.A.; Oltvai, Z.N.; Barabási, A.L. Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks. Science 2002, 297, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamic, L.A.; Adar, E. Friends and neighbors on the web. Soc. Netw. 2003, 25, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lü, L.; Zhang, Y.C. Predicting missing links via local information. Eur. Phys. J. B 2009, 71, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, L.; Jin, C.H.; Zhou, T. Similarity index based on local paths for link prediction of complex networks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2009, 80, 046122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, F.; Gul, H.; Muhammad, I.; Uddin, I. Link prediction using node information on local paths. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 557, 124980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L. A new status index derived from sociometric analysis. Psychometrika 1953, 18, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perozzi, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Skiena, S. Deepwalk: Online learning of social representations. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 August 2014; pp. 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Lu, W.; Xu, Q. Grarep: Learning graph representations with global structural information. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Melbourne, Australia, 19–23 October 2015; pp. 891–900. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Cui, P.; Zhu, W. Structural deep network embedding. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1225–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, Q.; Fang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, G. Automatic pearl classification machine based on a multistream convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 65, 6538–6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niepert, M.; Ahmed, M.; Kutzkov, K. Learning convolutional neural networks for graphs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 2014–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Xie, X.; Guo, M. Graphgan: Graph representation learning with generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Song, G. Sepne: Bringing separability to network embedding. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 4261–4268. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Guo, P.; Mao, Z.; Ti, Z.; He, Y.; Nian, F.; Zhang, R.; Ma, N. Multi-scale contrastive learning via aggregated subgraph for link prediction. Appl. Intell. 2025, 55, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.A.; Vladimir, F.F.; Huang, D.S. Variational graph neural network with diffusion prior for link prediction. Appl. Intell. 2025, 55, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.; Latora, V.; Pulvirenti, A. MultiSAGE: A multiplex embedding algorithm for inter-layer link prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.13223. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, E.; Berahmand, K.; Li, Y. A new link prediction in multiplex networks using topologically biased random walks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 151, 111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Shan, N.; Chen, X. Effective link prediction in multiplex networks: A TOPSIS method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 177, 114973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, N.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, S.; Chen, X. Supervised link prediction in multiplex networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 203, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, F.; Zhao, X. LPGRI: A global relevance-based link prediction approach for multiplex networks. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. Stat 2017, 1050, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, M.; Micenkova, B.; Rossi, L. Combinatorial analysis of multiple networks. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.; Katz, E.; Menzel, H. The diffusion of an innovation among physicians. Sociometry 1957, 20, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Ghobaei-Arani, M.; Shahidinejad, A. Data replica placement approaches in fog computing: A review. Clust. Comput. 2022, 25, 3561–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yang, C.; Peng, X.; Rezaeipanah, A. A novel similarity measure of link prediction in multi-layer social networks based on reliable paths. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickison, M.E.; Magnani, M.; Rossi, L. Multilayer Social Networks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De Domenico, M.; Nicosia, V.; Arenas, A.; Latora, V. Structural reducibility of multilayer networks. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J.A.; McNeil, B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, H.; Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2008; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The pascal visual object classes (voc) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liben-Nowell, D.; Kleinberg, J. The link prediction problem for social networks. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–8 November 2003; pp. 556–559. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.J. Projected gradient methods for nonnegative matrix factorization. Neural Comput. 2007, 19, 2756–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Aggarwal, C.C.; Yin, D.; Tang, J. Multi-dimensional graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Siam International Conference on Data Mining, SIAM, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2–4 May 2019; pp. 657–665. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Biswas, B. MNERLP-MUL: Merged node and edge relevance based link prediction in multiplex networks. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 60, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Biswas, B. HOPLP- MUL: Link prediction in multiplex networks based on higher order paths and layer fusion. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 3415–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Shakibian, H. Inter-layer similarity-based graph neural network for link prediction in social multiplex networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Web Research (ICWR), Tehran, Iran, 24–25 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Nodes | Edges | Layers |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 61 | 620 | 5 |

| CKM | 246 | 1551 | 3 |

| TF | 1564 | 30,882 | 2 |

| FF | 6407 | 30,882 | 3 |

| RA | 2640 | 4229 | 3 |

| SA | 4092 | 63,677 | 7 |

| Algorithm Name | Time Complexity |

|---|---|

| NMF | |

| MGCN | |

| MNER | |

| HOP | |

| LAGNN | |

| LATGCN | |

| Dataset | Layer | NMF | MGCN | MNER | HOP | LAGNN | VAR | LATGCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1 | 0.6634 | 0.8500 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.7900 | 0.8425 | 0.8825 |

| 2 | 0.8194 | 0.9527 | 0.9231 | 0.9231 | 0.8343 | 0.9527 | 0.9645 | |

| 3 | 0.7500 | 1.0000 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 4 | 0.6406 | 0.8889 | 0.7778 | 0.6667 | 0.8395 | 0.9012 | 0.9136 | |

| 5 | 0.6717 | 0.8200 | 0.7500 | 0.7500 | 0.7450 | 0.8210 | 0.8350 | |

| CKM | 1 | 0.6583 | 0.8290 | 0.5111 | 0.4889 | 0.8201 | 0.8353 | 0.8405 |

| 2 | 0.7139 | 0.8543 | 0.4800 | 0.5000 | 0.8169 | 0.9169 | 0.9237 | |

| 3 | 0.6695 | 0.8689 | 0.4186 | 0.4186 | 0.8131 | 0.8624 | 0.8758 | |

| TF | 1 | 0.3623 | 0.7963 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8401 | 0.7401 | 0.8862 |

| 2 | 0.3695 | 0.8200 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8200 | 0.7479 | 0.8717 | |

| FF | 1 | 0.6842 | 0.9516 | 0.2586 | 0.2414 | 0.7561 | 0.9862 | 0.9917 |

| 2 | 0.5408 | 0.8331 | 0.7917 | 0.6073 | 0.8647 | 0.8830 | 0.9014 | |

| 3 | 0.6945 | 0.7756 | 0.8055 | 0.5274 | 0.8101 | 0.8325 | 0.8455 | |

| RA | 1 | 0.4712 | 0.9217 | 0.2410 | 0.2086 | 0.7609 | 0.9328 | 0.9537 |

| 2 | 0.6330 | 0.9481 | 0.0202 | 0.0303 | 0.7241 | 0.9579 | 0.9746 | |

| 3 | 0.6364 | 1.0000 | 0.1667 | 0.3333 | 0.8166 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SA | 1 | 0.7868 | 0.9201 | 0.3060 | 0.2537 | 0.8213 | 0.9409 | 0.9660 |

| 2 | 0.7027 | 0.9798 | 0.3243 | 0.2432 | 0.8424 | 0.9887 | 0.9994 | |

| 3 | 0.6940 | 0.9150 | 0.6476 | 0.6160 | 0.7036 | 0.9384 | 0.9410 | |

| 4 | 0.6227 | 0.7602 | 0.4424 | 0.4131 | 0.8008 | 0.8636 | 0.8893 | |

| 5 | 0.9211 | 0.8160 | 0.6299 | 0.6417 | 0.8814 | 0.9231 | 0.9350 | |

| 6 | 0.6551 | 0.8000 | 0.7705 | 0.7262 | 0.7637 | 0.8413 | 0.8606 | |

| 7 | 0.8095 | 0.9427 | 0.3636 | 0.4545 | 0.9106 | 0.9513 | 0.9757 |

| Dataset | Layer | NMF | MGCN | MNER | HOP | LAGNN | VAR | LATGCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1 | 0.7391 | 0.7170 | 0.8740 | 0.8720 | 0.7179 | 0.7843 | 0.8263 |

| 2 | 0.7826 | 0.7429 | 0.8867 | 0.8916 | 0.7742 | 0.7879 | 0.8966 | |

| 3 | 0.6667 | 0.8571 | 0.6603 | 0.6626 | 0.7500 | 0.8571 | 1.0000 | |

| 4 | 0.5714 | 0.7200 | 0.8323 | 0.7895 | 0.7619 | 0.9365 | 0.9474 | |

| 5 | 0.7556 | 0.7037 | 0.7461 | 0.7372 | 0.7619 | 0.8011 | 0.8163 | |

| CKM | 1 | 0.7321 | 0.7258 | 0.7298 | 0.7212 | 0.7037 | 0.8174 | 0.8348 |

| 2 | 0.7705 | 0.7333 | 0.7138 | 0.7261 | 0.7010 | 0.8730 | 0.8837 | |

| 3 | 0.7308 | 0.7576 | 0.6925 | 0.6933 | 0.7007 | 0.8214 | 0.8430 | |

| TF | 1 | 0.2640 | 0.7038 | 0.5000 | 0.5000 | 0.7133 | 0.7557 | 0.7648 |

| 2 | 0.2859 | 0.7260 | 0.5000 | 0.5000 | 0.7377 | 0.7515 | 0.7705 | |

| FF | 1 | 0.5000 | 0.9752 | 0.6293 | 0.6207 | 0.6393 | 0.9612 | 0.9883 |

| 2 | 0.5850 | 0.8185 | 0.8115 | 0.7910 | 0.7490 | 0.8185 | 0.8254 | |

| 3 | 0.7396 | 0.7945 | 0.7833 | 0.7574 | 0.7306 | 0.7870 | 0.7953 | |

| RA | 1 | 0.3349 | 0.7240 | 0.5776 | 0.5970 | 0.6652 | 0.9195 | 0.9406 |

| 2 | 0.0784 | 0.6988 | 0.5094 | 0.5144 | 0.6625 | 0.9455 | 0.9550 | |

| 3 | 0.4286 | 0.6667 | 0.5833 | 0.6666 | 0.6667 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SA | 1 | 0.6765 | 0.7228 | 0.6527 | 0.6265 | 0.7679 | 0.9239 | 0.9330 |

| 2 | 0.4898 | 0.8200 | 0.6621 | 0.6216 | 0.7391 | 0.9524 | 0.9880 | |

| 3 | 0.3392 | 0.7480 | 0.7803 | 0.7644 | 0.6232 | 0.8882 | 0.8990 | |

| 4 | 0.5016 | 0.6892 | 0.6939 | 0.6797 | 0.7401 | 0.8186 | 0.8358 | |

| 5 | 0.8645 | 0.6875 | 0.8138 | 0.8198 | 0.8136 | 0.8724 | 0.8770 | |

| 6 | 0.5535 | 0.7227 | 0.8350 | 0.8318 | 0.6997 | 0.7849 | 0.7884 | |

| 7 | 0.5000 | 0.8214 | 0.6817 | 0.7272 | 0.8400 | 0.9412 | 0.9588 |

| Dataset | Layer | NMF | MGCN | MNER | HOP | LAGNN | VAR | LATGCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1 | 0.6025 | 0.8184 | 0.0534 | 0.0524 | 0.8170 | 0.8474 | 0.8817 |

| 2 | 0.8078 | 0.9491 | 0.0441 | 0.0471 | 0.8361 | 0.9541 | 0.9682 | |

| 3 | 0.7500 | 1.0000 | 0.0408 | 0.0625 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 4 | 0.6052 | 0.8182 | 0.0337 | 0.0372 | 0.8649 | 0.8042 | 0.8394 | |

| 5 | 0.6018 | 0.7941 | 0.0337 | 0.0316 | 0.6836 | 0.7833 | 0.8040 | |

| CKM | 1 | 0.5959 | 0.7736 | 0.0154 | 0.0162 | 0.7838 | 0.7845 | 0.7936 |

| 2 | 0.6380 | 0.8411 | 0.0158 | 0.0180 | 0.8132 | 0.9034 | 0.9139 | |

| 3 | 0.6045 | 0.8347 | 0.0184 | 0.0193 | 0.8363 | 0.8398 | 0.8430 | |

| TF | 1 | 0.3961 | 0.7508 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.8549 | 0.6546 | 0.8874 |

| 2 | 0.3998 | 0.7874 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.8361 | 0.6634 | 0.8488 | |

| FF | 1 | 0.6842 | 0.9756 | 0.0100 | 0.0114 | 0.7992 | 0.9842 | 0.9909 |

| 2 | 0.5850 | 0.7727 | 0.0014 | 0.0037 | 0.8827 | 0.8718 | 0.8831 | |

| 3 | 0.6081 | 0.6932 | 0.0028 | 0.0085 | 0.7872 | 0.7852 | 0.7990 | |

| RA | 1 | 0.4627 | 0.8867 | 0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.7734 | 0.8918 | 0.9227 |

| 2 | 0.6544 | 0.9205 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 0.7644 | 0.9583 | 0.9587 | |

| 3 | 0.6364 | 1.0000 | 0.0103 | 0.0186 | 0.8626 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SA | 1 | 0.7910 | 0.9265 | 0.0074 | 0.0062 | 0.8348 | 0.9067 | 0.9322 |

| 2 | 0.7027 | 0.9797 | 0.0166 | 0.0140 | 0.8671 | 0.9901 | 0.9994 | |

| 3 | 0.5683 | 0.8964 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.7320 | 0.8981 | 0.9096 | |

| 4 | 0.5166 | 0.7388 | 0.0015 | 0.0014 | 0.8156 | 0.8204 | 0.8424 | |

| 5 | 0.8821 | 0.8370 | 0.0084 | 0.0087 | 0.8762 | 0.8768 | 0.8876 | |

| 6 | 0.5368 | 0.7543 | 0.0028 | 0.0043 | 0.7865 | 0.7924 | 0.8138 | |

| 7 | 0.8095 | 0.9474 | 0.0049 | 0.0127 | 0.9236 | 0.9583 | 0.9741 |

| Dataset | Layer | NMF | MGCN | MNER | HOP | LAGNN | VAR | LATGCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1 | 0.6842 | 0.6250 | 0.1901 | 0.1241 | 0.7250 | 0.7250 | 0.7898 |

| 2 | 0.7917 | 0.6538 | 0.1449 | 0.1459 | 0.7308 | 0.7308 | 0.8846 | |

| 3 | 0.7500 | 0.8333 | 0.0258 | 0.0219 | 0.6667 | 0.8333 | 1.0000 | |

| 4 | 0.6250 | 0.6111 | 0.0715 | 0.0334 | 0.7222 | 0.9322 | 0.9445 | |

| 5 | 0.7105 | 0.6000 | 0.1028 | 0.0700 | 0.7500 | 0.7556 | 0.7750 | |

| CKM | 1 | 0.6591 | 0.6458 | 0.0132 | 0.0193 | 0.6667 | 0.7813 | 0.8021 |

| 2 | 0.7143 | 0.6491 | 0.0144 | 0.0105 | 0.7456 | 0.8596 | 0.8684 | |

| 3 | 0.6667 | 0.6863 | 0.0122 | 0.0107 | 0.5980 | 0.7887 | 0.8138 | |

| TF | 1 | 0.3544 | 0.5851 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.6301 | 0.6899 | 0.7012 |

| 2 | 0.3580 | 0.6343 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | 0.7068 | 0.6832 | 0.7114 | |

| FF | 1 | 0.6667 | 0.9758 | 0.0048 | 0.0081 | 0.6452 | 0.9608 | 0.9884 |

| 2 | 0.5627 | 0.7864 | 0.0342 | 0.0293 | 0.7159 | 0.7867 | 0.7927 | |

| 3 | 0.6941 | 0.7503 | 0.0298 | 0.0358 | 0.7136 | 0.7427 | 0.7527 | |

| RA | 1 | 0.4765 | 0.6226 | 0.0029 | 0.0022 | 0.5000 | 0.9139 | 0.9371 |

| 2 | 0.5204 | 0.5932 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.5045 | 0.9455 | 0.9546 | |

| 3 | 0.6364 | 0.5001 | 0.0026 | 0.0417 | 0.5000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| SA | 1 | 0.7519 | 0.6301 | 0.0050 | 0.0029 | 0.7692 | 0.9201 | 0.9290 |

| 2 | 0.6622 | 0.7805 | 0.0076 | 0.0046 | 0.7073 | 0.9512 | 0.9879 | |

| 3 | 0.5165 | 0.6719 | 0.0140 | 0.0173 | 0.6578 | 0.8802 | 0.8902 | |

| 4 | 0.5550 | 0.5921 | 0.0024 | 0.0033 | 0.7460 | 0.8051 | 0.8122 | |

| 5 | 0.8700 | 0.5829 | 0.0210 | 0.0170 | 0.8052 | 0.8667 | 0.8708 | |

| 6 | 0.5982 | 0.6307 | 0.0116 | 0.0229 | 0.7241 | 0.7321 | 0.7369 | |

| 7 | 0.6667 | 0.7916 | 0.0467 | 0.0106 | 0.8333 | 0.9375 | 0.9570 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; He, Y. A Link Prediction Algorithm Based on Layer Attention Mechanism for Multiplex Networks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233803

Yang M, He Y. A Link Prediction Algorithm Based on Layer Attention Mechanism for Multiplex Networks. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233803

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Mingzhou, and Yongqi He. 2025. "A Link Prediction Algorithm Based on Layer Attention Mechanism for Multiplex Networks" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233803

APA StyleYang, M., & He, Y. (2025). A Link Prediction Algorithm Based on Layer Attention Mechanism for Multiplex Networks. Mathematics, 13(23), 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233803