1. Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs) play a vital role in thermodynamics, governing how quantities such as pressure, temperature, and velocity evolve within fluids and gases. These equations form the foundation for modeling thermodynamic behavior, where properties like internal energy and enthalpy, essential for calculating heat and work in industrial processes, are not directly measurable but can be inferred by solving NLPDEs that incorporate conservation laws and material relations. Despite their importance, the nonlinear nature of these equations poses major analytical and numerical challenges. Considerable research has been devoted to finding exact and approximate solutions, yet many problems remain unresolved due to the complex, high-order structure of NLPDEs [

1,

2]. They describe the spatial and temporal evolution of key physical variables such as temperature, displacement, and wave functions, making them indispensable for understanding real-world systems. However, their inherent complexity often prevents the derivation of straightforward analytical solutions [

3]. In recent years, NLPDEs have gained increased attention for their applications in diverse fields, including electrical circuits, control theory, and wave propagation areas deeply rooted in nonlinear physical processes [

4]. Obtaining analytical solutions to these equations not only clarifies the underlying mechanisms of nonlinear phenomena but also offers valuable insight for future theoretical developments. A solid grasp of nonlinear science is therefore essential for interpreting complex systems characterized by non-proportional and dynamic relationships [

5,

6].

Solitons are very important for simulating wave behavior in nonlinear and dispersive media in numerous fields of science due to their exceptional stability and particle-like behavior in nonlinear systems. In the fields of applied mathematics and mathematical physics, solitons are occasionally employed to depict phenomena such as plasma waves, fiber optic pulses, and waves in shallow water. They play an essential role in engineering and technology. Soliton solutions of NLPDEs are highly significant in mathematical physics due to their deep connection with nonlinear wave phenomena, field theory, and integrable systems [

7]. Understanding the role of nonlinear dynamics in complicated physical systems is greatly aided by these solutions since they are accurate, stable, and constrained. In the field of mathematical physics, solitons are not only distinct phenomena; they often represent the fundamental behaviors of objects in various models. The capacity of waves to preserve their form and energy after interactions with other waves makes nonlinear dynamics and wave propagation significant subjects of study across several fields [

8,

9,

10]. Solitons have many technical uses, including optical coupling devices, controllers, sensors, and magneto-optic waveguide structures [

11,

12,

13]. The soliton solutions of the Van der Waals equation are of considerable significance for both theoretical and practical research in mathematical physics [

14].

A more profound comprehension of physical behavior is facilitated by the development of exact solutions for a diverse array of physical processes. Because they establish the foundation for further investigation. The behavior of a physical system is usually described using ordinary or partial differential equations, which help in finding analytical or approximate solutions. PDEs serve as a powerful mathematical framework for representing complex processes in nature and industry. Numerous researchers have devised alternative approaches to address these challenges. A variety of techniques have been employed over the years: the truncated Painlevé technique [

15], Hamiltonian analysis [

16], the improved generalized exponential rational function [

17], the Adomian decomposition technique [

18], sensitivity analysis [

19], Darboux transformation [

20], the Bernoulli

-expansion method [

21], the modified Sardar sub-equation method [

22], the compact difference method [

23], the

-expansion method [

24], quasi-linear and monotone iterative methods [

25], the Riccati equation mapping method [

26], bifurcation analysis [

27], neural networks [

28], etc.

This study examines the nonlinear dynamics of soliton solutions of Van der Waals gas systems, acknowledging their important applications in numerous fields when dealing with real gases, especially at high pressures and low temperatures, where deviations from the ideal behavior become significant. To identify and simulate the nonlinear behaviors of the proposed model, we apply advanced integration techniques, including the generalized Arnous method [

29], the modified F-expansion method [

30], and the modified generalized Riccati equation method [

31]. Furthermore, we utilize the multilayer perceptron regressor neural network algorithm, a neural network-based model [

32], to predict outcomes based on actual analytical data. Machine learning is used to improve task performance without dependence on explicitly coded instructions, enabling computers to learn from and anticipate patterns in information. Machine learning encompasses a variety of fields, including supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. This research focuses on supervised learning, which entails training a model using labeled data. The dataset is partitioned into training and testing subsets to assess the model’s prediction efficacy. More importantly, the research extends further mathematical derivations by conducting comprehensive chaos analysis, using tools such as return maps, bifurcation diagrams, power spectra, and chaotic attractors to thoroughly examine the system’s dynamical structure. This comprehensive approach enhances the theoretical understanding of nonlinear discrete electrical lattices and provides a solid basis for future research on their control, stability, and application in engineering systems. The results demonstrate the suitability and applicability of the methodologies employed, which are important tools with significant implications for the scientific and engineering fields. These methodologies achieve substantial results that contribute to the advancement of numerous scientific disciplines and enable the development of innovative waveforms and solitons.

The remaining sections of this paper are delineated as follows:

Section 2 outlines the governing mathematical model. Soliton solutions are derived in

Section 3 using the mGREM, the modified F-expansion method, and the generalized Arnous method.

Section 4 provides a comprehensive elucidation of the graphical depiction of several solutions. The machine learning application is presented in

Section 5, the chaotic analysis is discussed in

Section 6, and the conclusion is provided in

Section 7.

2. The Governing Equation

Well-known Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik Van der Waals developed the Van der Waals equation in 1873 to deal with the Ideal Gas Law’s limitations in explaining how real gases behave. He believed that the equation more accurately described the physical state of real gases and therefore became a key part of the study of fluid dynamics and compressible fluids. Systems of conservation laws combining hyperbolic and elliptic features can be used to explain a wide variety of physical phenomena, but there has been a lot of theoretical discussion about hybrid systems and their applications in various works [

33,

34]. In this work, we study the nonlinear dynamic behavior of the Van der Waals gas system [

35,

36,

37,

38], read as

where

and

V represent pressure, velocity, and specific volume, respectively. In addition,

denotes the viscosity, where

stands for the interfacial capillarity coefficient. The structure of the function

is similar to that of Van der Waals, as stated in [

39]. The one-dimensional longitudinal isothermal motion in elastic bars or fluids is described by the P-system in Equation (

1). The corresponding eigenvalues are

. The system is a mixed hyperbolic–elliptic type for certain material models, as the constitutive pressure function may not be monotone.

Moreover, the proposed model has been analyzed in the literature using various approaches. In [

35], sensitivity analysis and bifurcation analysis were conducted, invesitgating multistability and chaotic behavior, while the exact solutions were obtained in [

36] through the use of the exponential expansion method. Similarly, in [

37], the

expansion and advance

-expansion function approaches were applied to secure a variety of solutions, where in [

38], Kudryashov’s technique, the Sine-Gordon equation, and the Projective Riccati equation were employed to study the proposed system. This study uses new advanced techniques to examine the exact solution of the proposed model to gain a deeper understanding of its nonlinear behavior.

5. Machine Learning Validation

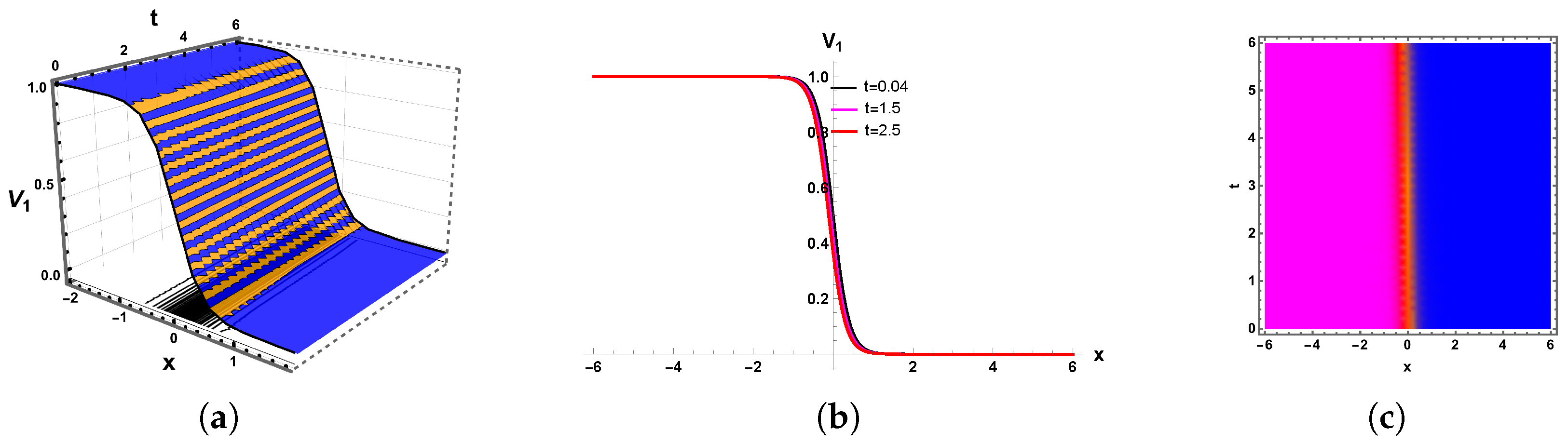

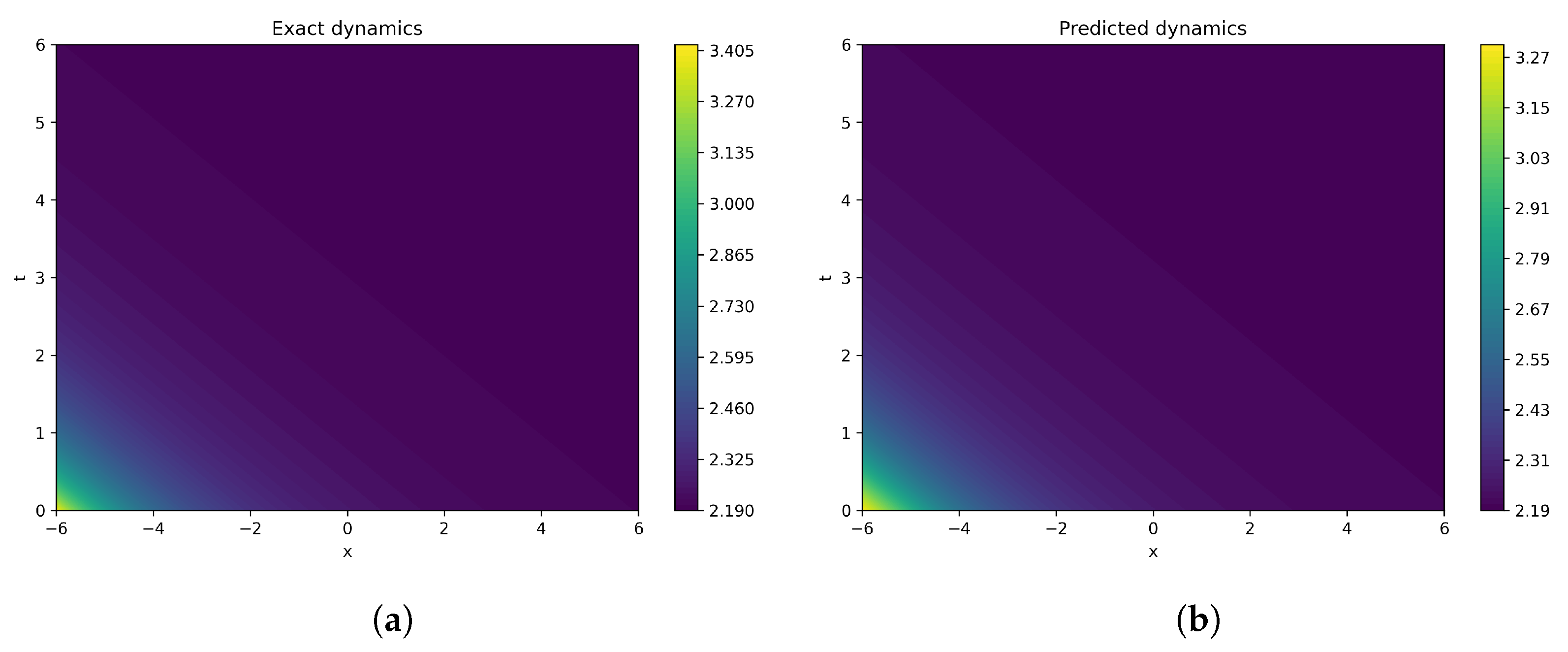

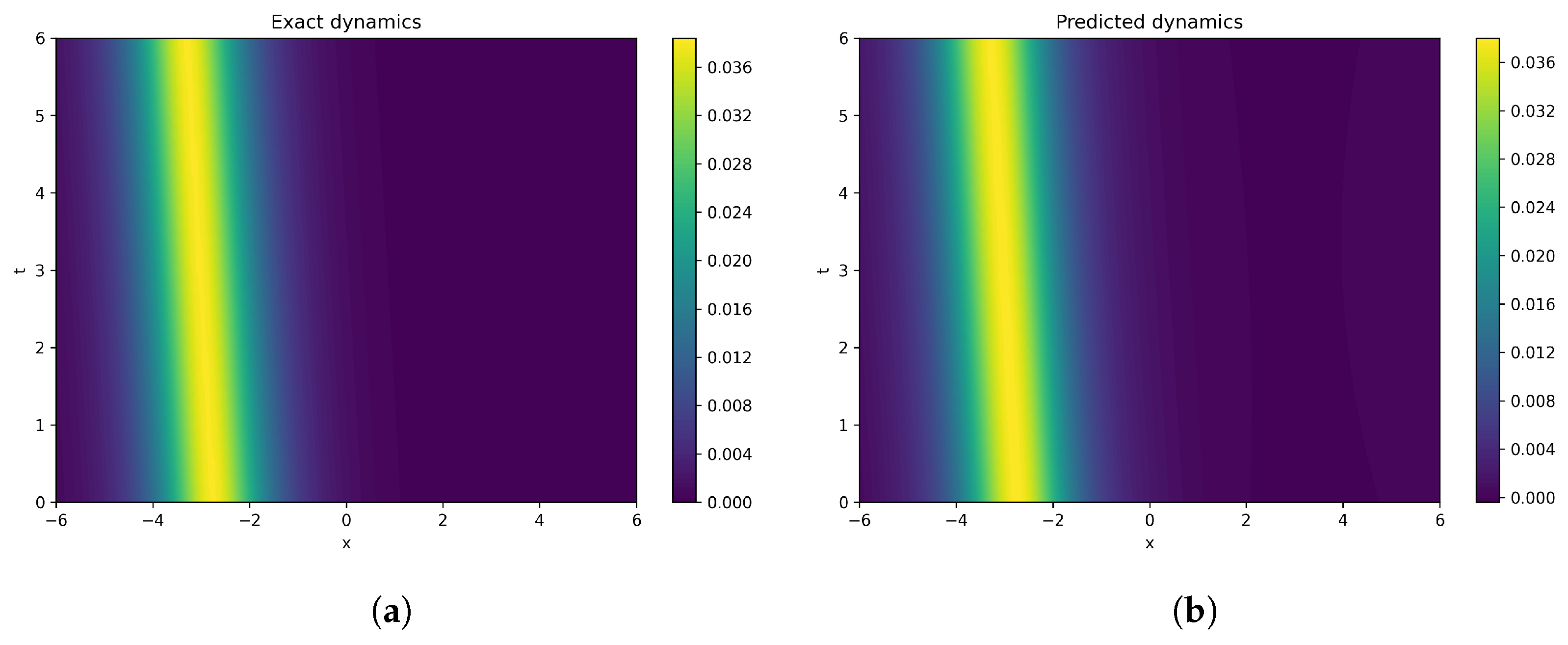

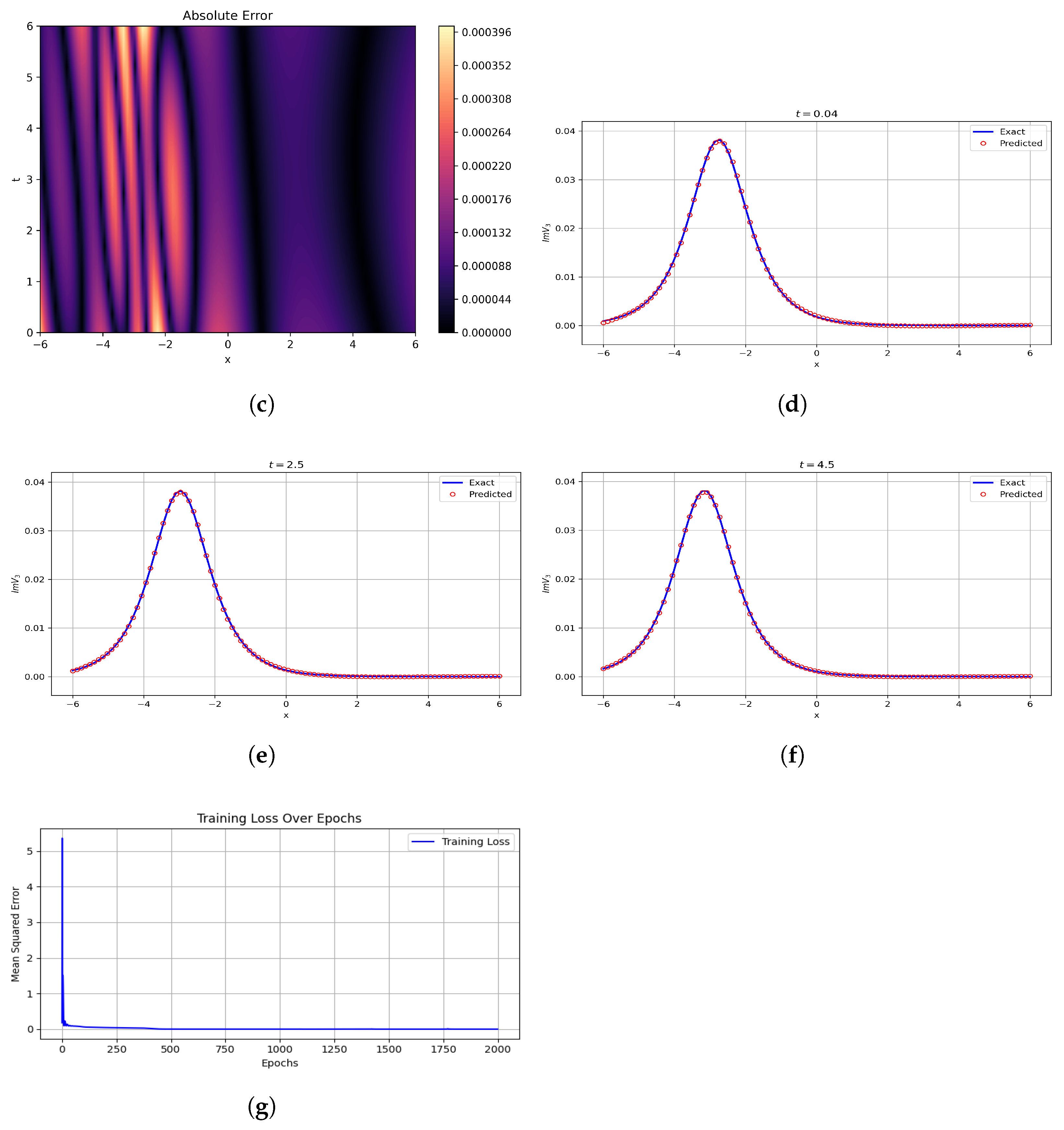

The physical behaviour of solution (

19) is mentioned in

Figure 1. The MLP regressor neural network, over 1500 epochs, yields results closely related to the actual data. Corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss values are provided below.

Moreover, the graph of the actual behaviour of solution (

22) is presented in

Figure 2 with different parametric values. Next, the MLP regressor neural network gives the almost similar to the actual data of the studied solution over 5000 epochs. Corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss values are provided below.

Furthermore, the actual and predicted behavior of solution (

27) with the MLP regressor neural network is observed and discussed with the following corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss.

Moreover, over 5000 epochs, regarding the physical behaviour for solution (

30), the actual and predicted data obtained through the application of the MLP regressor machine learning algorithm are approximately near to the results shown in

Figure 4. Corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss values are provided below.

Furthermore, the dynamics of solution (

31) with the actual and predicted behaviour over 10,000 epochs were observed and found to be similar to that in

Figure 5, which was generated for solution (

31). Corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss values are provided below.

Moreover, regarding solution (

36), its actual and predicted behaviour over 2000 epochs was observed, and it was found to be like in

Figure 6. Corresponding epoch-wise loss values, error tables, figures, and MSE loss values are provided below.

Hence, the MLP regressor demonstrates strong robustness and high predictive accuracy, making it a highly effective machine learning model for simulating and forecasting the physical behaviors described by the given equations. Its ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships, generalize well to unseen data, and deliver reliable performance across various scenarios underscores its suitability for this application. Additionally, the model’s adaptability to different parameter configurations and computational efficiency further enhance its practical utility in data-driven physical modeling.

7. Conclusions

The dynamical aspects of the Van der Waals gas system were the focus of this study. The newly developed methodologies, including the F-expansion approach, mGREM, and generalized Arnous method were successfully applied to analyze the target model. Moreover, a variety of solitary wave solutions, such as dark, bright, and kink types, were combined, and periodic, hyperbolic, and exponential solutions were extracted. The extracted solutions are shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 through the assistance of different parametric values. Solitary waves play a significant role in the Van der Waals gas model as they represent stable, localized disturbances with varying density or pressure that propagate without dissipation. These nonlinear waves arise due to the interplay between the gas’s non-ideal behavior (accounted for by Van der Waals corrections) and its thermodynamic properties, providing key insights into shock waves, phase transitions, and stability in dense gases. The graphs of these solitary waves, typically plotting pressure, density, or velocity against position, reveal their characteristic shape-preserving nature, helping researchers analyze how molecular interactions influence wave dynamics in real gases. Such studies are valuable in fields like fluid dynamics, condensed matter physics, and plasma physics, where understanding nonlinear wave behavior is essential for modeling complex systems. The MLP regressor effectively predicted the outcomes, yielding results that closely align with both our expected values and computational benchmarks, as shown in

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. Moreover, the training epochs as well as comparison of the exact and predicted dynamics of the solutions were discussed in the

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

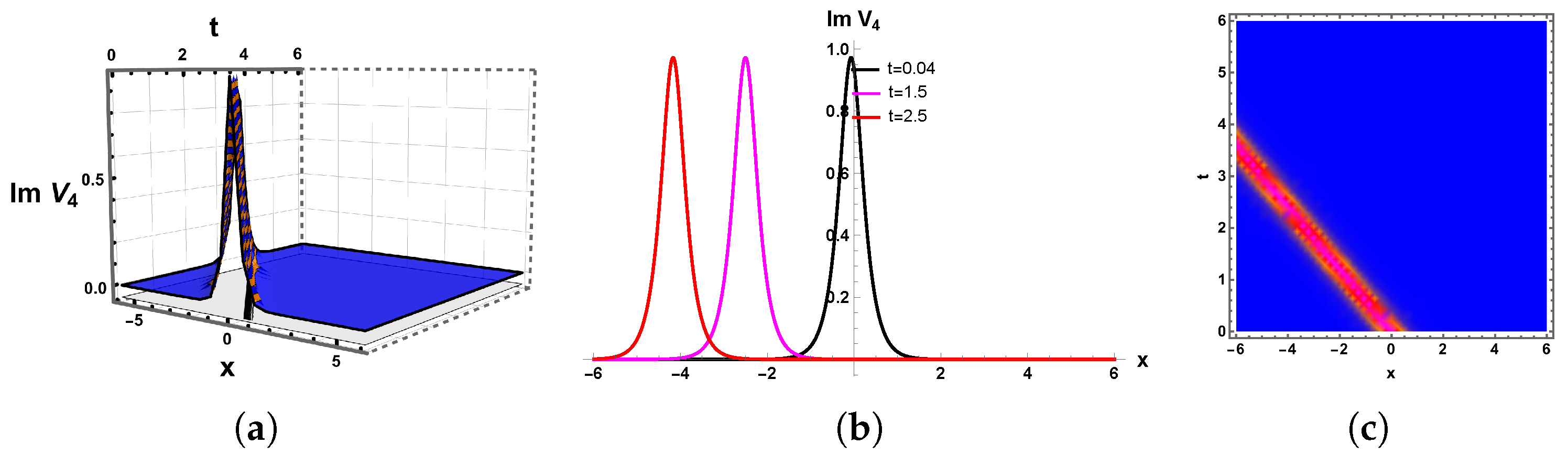

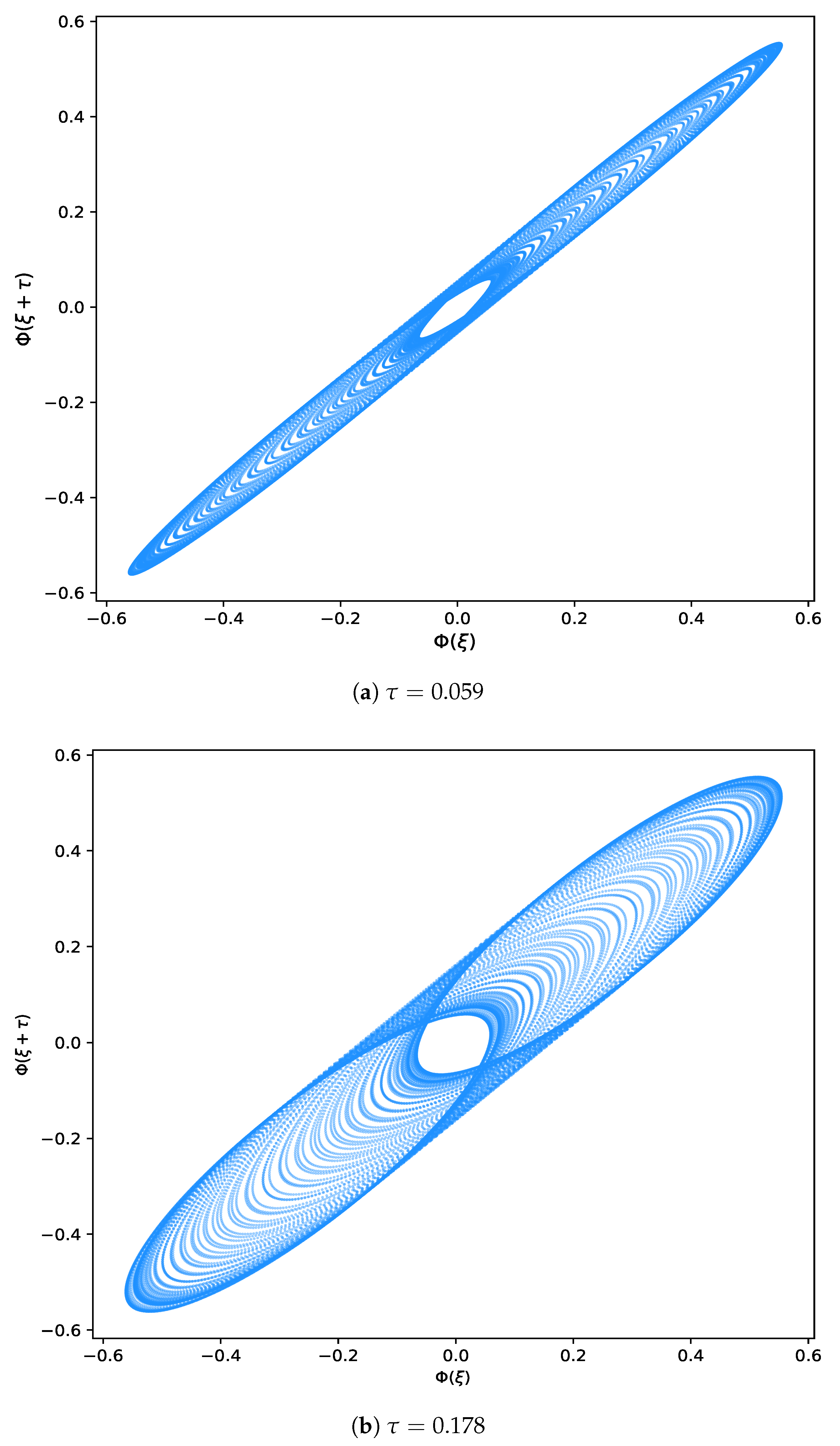

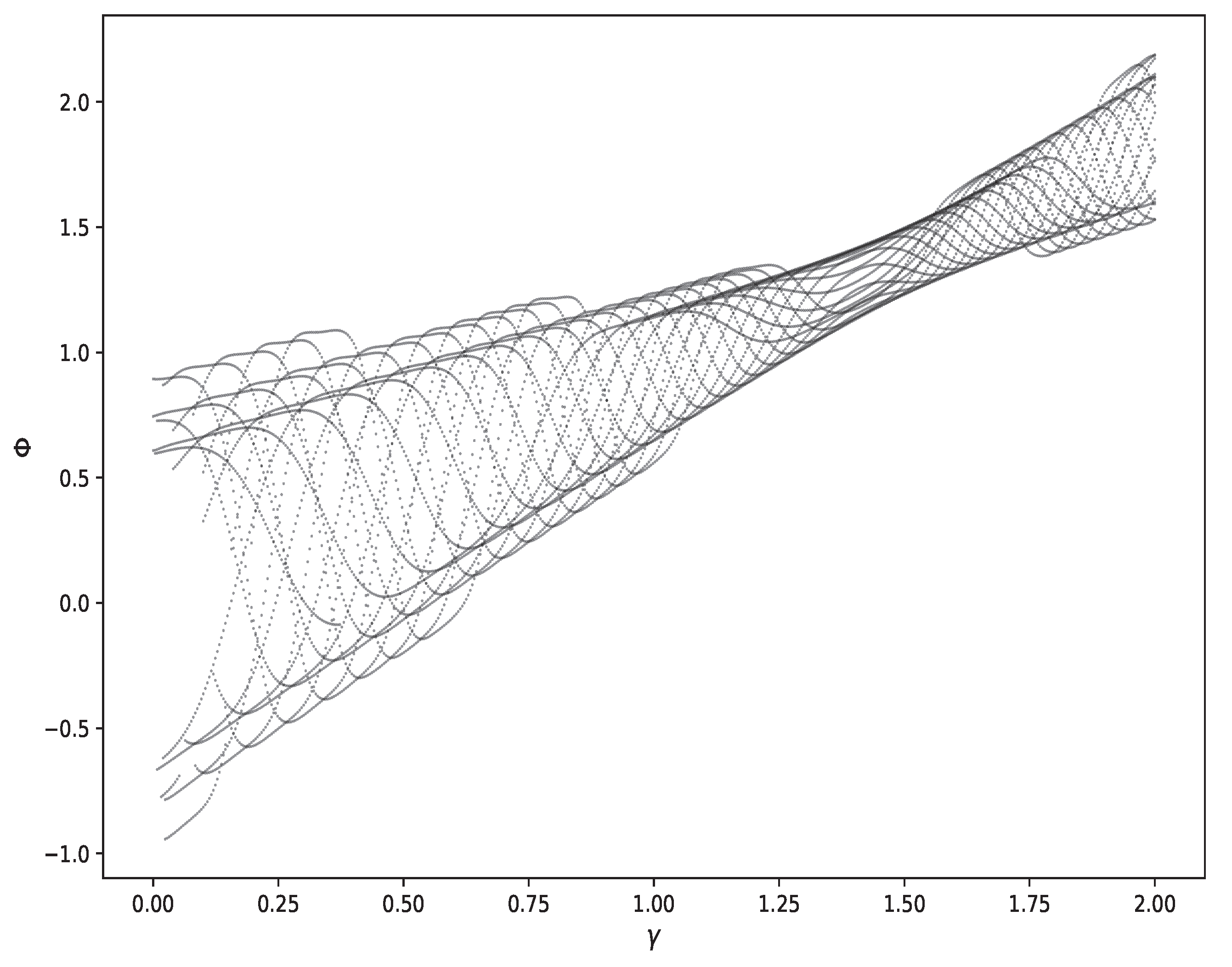

Table 12. The model demonstrated high accuracy, with predictions consistently approximating the target values within an acceptable margin of error. Its strong performance confirms the MLP regressor’s capability to reliably capture the underlying patterns in the data, making it a robust tool for predictive modeling in this context. For even greater precision, future refinements could include hyperparameter tuning, feature optimization, or ensemble techniques to further minimize deviations and enhance predictive consistency. Moreover, the inclusion of chaotic analysis, complemented by power spectra, return maps, chaotic attractors, and bifurcation diagrams, depicted the sensitive dependence on initial conditions and the complex structure of the system’s phase space.

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 were sketched for the visual representation of the chaotic techniques based on initial conditions and parametric values. These graphical tools collectively presented both qualitative and visual insights into the nonlinear dynamics and instabilities inherent in the studied model. The obtained solutions are relevant to several fields such as nonlinear dynamics, mathematical physics, engineering, and applied sciences. Researchers interested in the framework of nonlinear problems in applied sciences may find these findings interesting.

In addition, the generalized Arnous method, the modified F-expansion method, and the mGREM are all effective techniques for obtaining exact solutions of NLPDEs, each with its own strengths and limitations. The generalized Arnous method is flexible and capable of producing a wide range of solutions, including soliton and periodic forms, but it involves multiple arbitrary parameters, making validation more complex. The modified F-expansion method provides a systematic and straightforward way to generate hyperbolic, trigonometric, and periodic solutions, though it can become cumbersome for higher-order equations and may produce repetitive forms. The mGREM efficiently yields soliton, kink, and rational solutions by reducing the PDE to a solvable first-order ODE, but it is limited to equations compatible with the Riccati framework and can lead to complex algebraic systems. Overall, while all three methods produce rich solution families, they differ in formulation, complexity, and the types of solutions they most naturally generate. In future, the proposed methodologies can be employed to study various nonlinear dynamic behaviors of higher-dimensional systems with external effects, through stability analysis and the exploration of real-world applications.