Abstract

Index modulation (IM) has attracted increasing research attention in recent years. Spatial modulation (SM) as a popular IM scheme is effective to increase spectral efficiency using the antenna index to transmit extra information bits. It can also address some issues that occur in multiple-input multiple-output systems, such as inter-channel interference and inter-antenna synchronization. Artificial intelligence, especially deep learning (DL), has made significant inroads in wireless communication. Recently, more researchers have started to apply DL methods to IM-based applications such as signal detection. Many results have proven that DL methods can achieve breakthroughs in metrics like bit error rate (BER) and time complexity compared to conventional signal detection methods. However, the problem of how to design this novel method in practical scenarios is far from fully understood. This article surveys several DL-based signal detection methods for IM and its variants. Moreover, we discuss the performance of different neural network structures, some of which can achieve better performance compared to original neural network. In the implementation, trade-offs between BER and time complexity, as well as neural network’s training time, are discussed. Several simulation results are provided to demonstrate how the DL method in signal detection of SM can lead to improvements in BER and time complexity. Finally, some challenges and open issues that suggest future research directions are discussed.

MSC:

94-10

1. Introduction

Multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) is a widely used technology in current wireless communication systems, which can improve data transmission rate and increase channel capacity. However, this technology faces some practical issues such as inter channel interference (ICI) and inter antennas synchronization (IAS). Consequently, to solve these problems, spatial modulation (SM) as a typical index modulation (IM) was proposed in [1]. In SM, at each time slot, only one antenna is active, and a specific number of information bits are mapped to the index part and constellation part, where index part is used to select the activated antenna while the constellation part decides the constellation symbol.

However, SM only activates one antenna at each time slot, which results in a low data rate. To address this issue, variants of SM have been proposed. For instance, generalized SM (GSM) and quadrature SM (QSM) use more than one antenna to transmit signals simultaneously. Enhanced SM (ESM) considers more than one constellation symbol, and different numbers of transmit antennas match different constellation symbols. Offset SM (OSM) addresses the radio-frequency (RF) chain switching problem. Signed QSM (SQSM) and parallel QSM (PQSM) are variants of QSM that can provide higher spectral efficiency. Because SM offers tremendous benefits, research on SM and its variants is an attractive area. More researchers are paying increasing attention to this area.

For SM and its variants, many signal detection algorithms have been proposed. Among of them, maximum-likelihood (ML) has the best bit error rate (BER) performance. Yet its complexity increases exponentially with transmit antennas increase. In order to reduce the complexity, some methods are proposed, such as zero-forcing (ZF) method and minimum mean-square error (MMSE) method. It is clear that these methods can reduce complexity and demodulation time significantly but the BER performance is not as good as that of the ML method. In order to strike a balance between the BER and complexity, researchers are endeavoring to propose novel methods. In the course of this endeavor, the emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technology has been brought into consideration.

AI has been a highly popular technology in recent years, with deep learning (DL) being a particularly prominent and widely studied subfield. DL has achieved unprecedented breakthroughs in areas such as natural language processing and image processing. In wireless communication, DL also has made profounds inroads in some area, like channel estimation, channel coding, antenna selection. After these pioneering works, significant attention has been paid to the use of DL method especially neural network to detect the signal in SM and its variants and some achievements have been made in recent years. Through these research, it is clear that DL method can approximately achieve the optimal BER performance and has lower complexity than ML. Despite lots of research activity on neural network-based signal detectors in SM over the last several years, there still remain many technical challenges of using this technique in some practical scenarios. The aim of this article is two-fold:

- To present a comprehensive overview on the current state of the art in signal detection of IM related systems.

- To define open issues for future research directions.

2. Overview of SM and Its Variants

SM is a novel technique that can avoid some issues in MIMO systems. In SM, a block of information bits is mapped into two information-carrying units, which include a symbol chosen from a constellation diagram and a unique transmit antenna selected from a set of transmit antennas. However, conventional SM has some drawbacks. For instance, one of the disadvantages of SM is that only one antenna is activated in each time slot, which results in a low data rate. To improve the performance of conventional SM, in recent research, several variants of SM have been proposed. In [2], generalized SM (GSM) was proposed, which uses more than one antenna to transmit signals. At the transmitter, more than one antenna is randomly selected to be activated, and these activated antennas simultaneously transmit symbols. It is clear that the spectral efficiency and data rate are increased in GSM. In [3], quadrature SM (QSM) was proposed which uses more than one antenna to transmit signals. The major difference between QSM and GSM is that in QSM, constellation symbols are expanded to in-phase and quadrature components. In QSM, the transmitter chooses one antenna to transmit the real part of the chosen symbol and the other antenna to transmit the imaginary part of the same symbol. Moreover, ICI is completely avoided since the two transmitted symbols are orthogonal in QSM. Compared to SM, QSM also has higher spectral efficiency. The authors in [4] proposed a new variant of SM called enhanced SM (ESM), which takes into account more than one signal constellation to increase the combination of antennas and symbols. When only one antenna is activated, that single antenna transmits symbols from the primary constellation. When two antennas are activated, both antennas simultaneously transmit symbols from the secondary constellation. The size of the secondary constellation is half of that of the primary constellation, which ensures that the number of bits for the transmitted symbols remains the same regardless of the number of antennas activated. Meanwhile, the secondary constellation is derived from the primary constellation through geometric interpolation. In addition to these variants, researchers also consider improving the drawbacks of SM from other perspectives. For instance, in [5], the authors proposed a novel SM called OSM. OSM aims to simplify the processing of RF switching by exploiting the channel state information (CSI) at the transmitter. To deal with different switching conditions, they proposed two types of OSM structures: static and dynamic modes. Specifically, in the static OSM structure, the RF chain is offset to a fixed antenna to avoid the RF chain switching problem. In the dynamic OSM structure, the RF chain is offset to a set of antennas to achieve improved performance with reduced switching frequency. By acquiring the current CSI, it ensures that each transmission is sent from the antenna with the best channel condition to the receiver. The spectral efficiency of OSM is the same as that of SM, but it solves the RF switching problem. In terms of BER performance, since OSM always chooses the transmit antenna with the best channel condition, it achieves better BER performance in comparison to SM. In [6], the authors proposed a new version of OSM with multiple receive antennas. Differential SM (DSM) [7] is another variant of SM that can avoid the need for CSI at both the transmitter and receiver. However, DSM exhibits a spectral efficiency loss when compared to SM. In [8] and [9], parallel QSM (PQSM) and signed QSM (SQSM) were proposed. These two schemes use techniques such as symbol inversion and sub-QSM blocks to increase spectral efficiency. In SQSM, the symbol is chosen from a single quadrant and then an inverse operation is performed. The original symbol and its inverse include two real parts and two imaginary parts. Then, antennas are chosen to transmit these four parts. In PQSM, transmit antennas are divided into several groups, with each group performing QSM in parallel. This parallel scheme can also be combined with other variants of SM, which have been investigated in [10,11], which can play an important role in MIMO communications. Considering the analysis of SM and its variants, we may conclude that SM can be a promising technique for next-generation communications if we appropriately utilize its advantages and address its drawbacks. The spectral efficiency of the aforementioned various SM is expressed in Table 1, where M represents modulation order, is the number of antennas in transmitter, is the number of activated antennas and C is the number of combination in ESM.

Table 1.

Spectral efficiency and complexity of various SM systems.

3. Conventional Signal Detection in SM

Signal detection is a significant process in communication systems. In this process, the BER and time complexity are the most important indicators. We know that the ML method is the optimal method, which achieves the best BER performance at the cost of the highest complexity. Aiming to reduce complexity while achieving the sub-optimal BER performance, several detection methods have been proposed. In [12], the ZF method was proposed where it calculates the conjugate transpose of the channel matrix to obtain the symbol. However, the ZF detector amplifies the noise, resulting in an increased BER. So, its performance is relatively poor at low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). To overcome this issue, MMSE detector [13] takes into account the influence of noise and achieves better BER performance than ZF detector. However, the MMSE detector needs to calculate the inverse and regularization terms of the channel matrix, therefore its computational complexity is higher than that of the ZF detector. At the same time, the performance of the MMSE detector is highly dependent on the accuracy of the CSI. These linear methods can reduce complexity, but their BER performance does not meet the required standards. In order to improve the performance of ZF and MMSE methods, some improved versions of these linear methods have been proposed in [14,15], which have lower BER. As well as that, simplifying the ML method is another perspective. In [16], the authors proposed a variant of the ML detector called pre-greedy ML (PGML). PGML calculates the instantaneous energy of the received signals in descending order and selects a subset of these signals. This new subset is then used to process the ML detector. PGML reduces complexity and achieves better BER performance than the conventional MMSE method. Moreover, some detection algorithms also have been mentioned in [17,18,19,20,21] to trade-off the BER and complexity. Overall, a considerable number of researchers have already explored a variety of signal detection methods in SM related systems that achieve both low complexity and low BER. In the following section, we will discuss some DL-based signal detectors in SM and its variants.

4. DL-Based Signal Detectors in SM

4.1. B-DNN Signal Detector in GSM

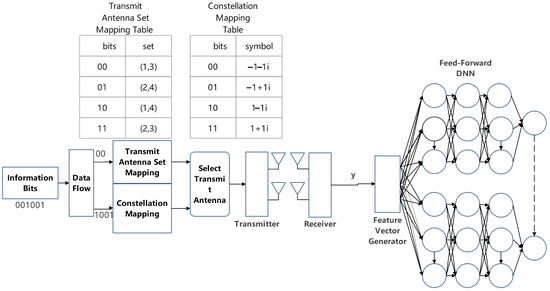

In [22], the authors proposed a new structure of deep neural network (DNN), called block DNN (B-DNN), for signal detection in GSM. As we have mentioned, GSM can activate more than one antenna to transmit signals simultaneously. In this B-DNN, it decomposes the detection process into parallel sub-networks, where smaller DNNs independently detect active antenna combinations and transmitted symbols, followed by an Euclidean distance-based soft constellation algorithm to refine decisions. This approach can reduce the training time while maintaining excellent performance. Figure 1 displays the system model. The raw data comprises the channel matrix and the received signal, and the channel is a quasi-static flat fading channel. The dataset consists of received symbols under such a channel condition along with the corresponding CSI, with 75 percent of the dataset used as the training set and the remaining 25 percent of the dataset as the validation set. While the feature vector includes received signal and channel matrix. Before inputting the feature vector into the neural network, a novel feature vector generator (FVG) called separate FVG (SFVG) is employed. The SFVG separates the complex values into their real and imaginary parts and concatenates these two parts to form the final vector, which can be used as the input vector. The activation functions used are softmax and rectified linear unit (ReLU) [23,24]. In order to further improve the model performance, for distinct modulation order, the authors also set distinct layer nodes. In the training phase, each smaller DNN is a feed-forward DNN architecture with L fully connected layers, including L-1 hidden layers. The output layer employs a softmax function to normalize predictions into a probability distribution over symbol classes. The loss function is categorical cross-entropy, which quantifies the discrepancy between the one-hot labels of predicted symbol and the true one-hot labels. Optimization is performed via stochastic gradient descent (SGD). The weights and biases are iteratively updated until the loss function converges, which ensure the model accurately learns the mapping from channel-affected signals to transmitted symbols. After the training phase, the B-DNN detector is applied to detect the signal. In Figure 2, the authors tested this model in 4 × 2 antenna configurations with QPSK symbol under perfect CSI. The simulation results show that the B-DNN-based method can achieve comparable performance compared to the ML method in terms of BER.

Figure 1.

Diagram of GSM communication system with B-DNN signal detection.

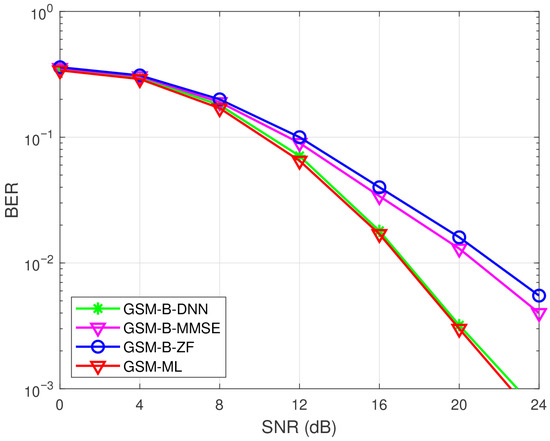

Figure 2.

BER performance of B-DNN and other detection methods in GSM with QPSK under MIMO system.

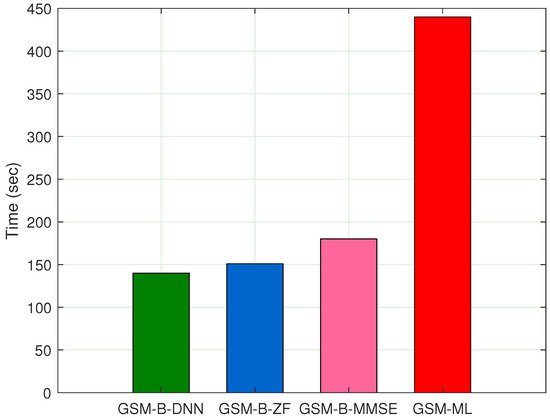

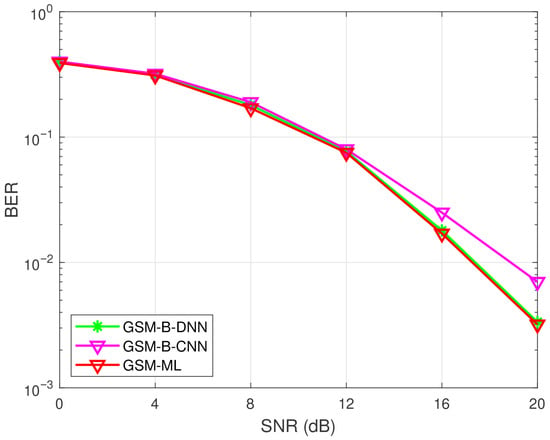

In Figure 3, we can find that the computational time of the B-DNN is less than that of the ML method. Compared to the ZF method and the MMSE method, the B-DNN detector performs better in terms of BER and computational time. In addition, a block convolutional neural network (B-CNN)-based signal detector is also tested. In Figure 4, the BER performance of B-CNN in antenna configuration with binary phase shift keying (BPSK) under perfect CSI is given, where we can find that the B-CNN method does not achieve the same BER performance as the B-DNN. In summary, adopting DNN for signal detection in GSM is feasible and considering the trade-off between BER and time complexity, a DNN-based detector is undoubtedly a good choice.

Figure 3.

Computational time of B-DNN in GSM with QPSK under MIMO system.

Figure 4.

BER performance of B-DNN, B-CNN, and ML in GSM with BPSK under MIMO system.

4.2. DNN Signal Detector in QSM

In [25], the authors proposed a DNN-based signal detection framework for QSM systems, addressing the trade-off between detection accuracy and computational complexity inherent in conventional methods. In this work, the channel entries are considered as Gaussian random variables with independent identical distribution with zero mean and variance . By leveraging a feed-forward DNN with three hidden layers (256-128-64 nodes), the approach processes channel and received signal via an SFVG and normalization to classify transmitted symbols and antenna indices. The SFVG explicitly decomposes the in-phase and quadrature components of signals and channels, preserving spatial correlations while converting complex data into a DNN-friendly format. Normalizing the FVG accelerates model convergence and enhances generalization capability. In the training phase, the feed-forward neural network consists of L fully linked layers and L-1 hidden layers. It uses cross-entropy as the loss function while the activation functions for hidden layers and output layers are ReLU and softmax, respectively, and the optimizer is SGD. In prediction, the simulation results prove that DNN can bring benefits to the signal detection process.

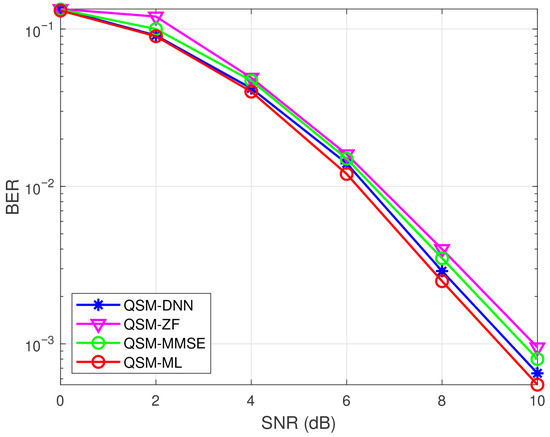

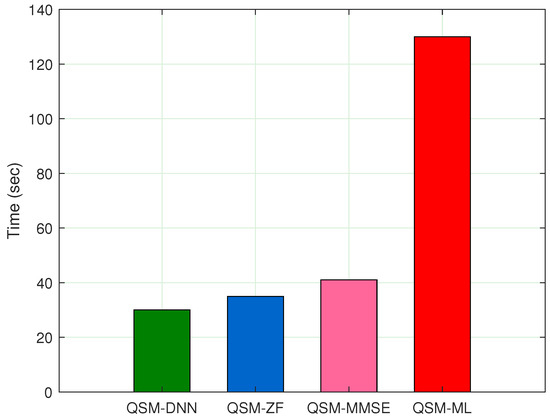

Figure 5 shows the BER performance of DNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under 4 × 4 antenna configuration case. The BER performance of DNN is better than that of ZF and MMSE, and it only has a small gap compared to ML. Figure 6 shows computational time of DNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under 4 × 4 antenna configuration case. It shows that the DNN method can reduce the time significantly when compared to ML. The scalability of the method is further validated in configurations, where it maintains superior BER and shows faster detecting efficiency than ML. Overall, it demonstrates the feasibility of using DNN in QSM for signal detection.

Figure 5.

BER performance of DNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under MIMO system.

Figure 6.

Computational time of DNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under MIMO system.

4.3. DNN Signal Detector in ESM

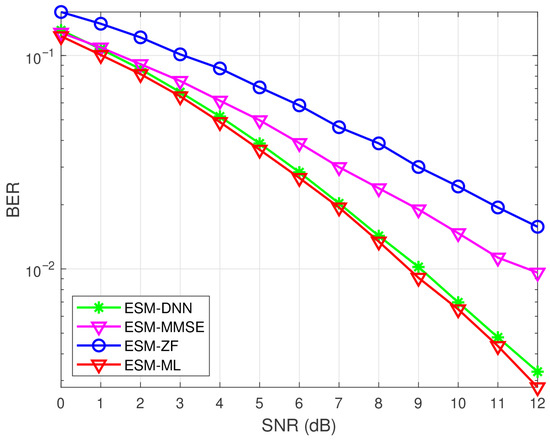

The aforementioned works have demonstrated the feasibility of using DNN to detect signals in GSM and QSM. In ESM, it is a challenging task to use DNN for signal detection due to that ESM uses more than one constellation symbol. The authors in [26] explored the feasibility of using DNN in ESM for signal detection under the quasi-static flat fading channel with Gaussian white noise. In order to mitigate overfitting, L2 regularization and a dropout scheme are also added into the neural network. Additionally, several neural networks are trained to adapt to various cases and the training phase is similar to the aforementioned work [26]. The simulation results show that DNN method provides remarkable performance of BER and computational time. Figure 7 shows the BER performance of B-DNN and other detection methods in ESM with QPSK under the 2 × 2 antenna configuration case. The BER performance of the B-DNN-based detector can approach the ML method and outperforms the MMSE and ZF methods.

Figure 7.

BER performanc of B-DNN and other detection methods in ESM with QPSK under MIMO system.

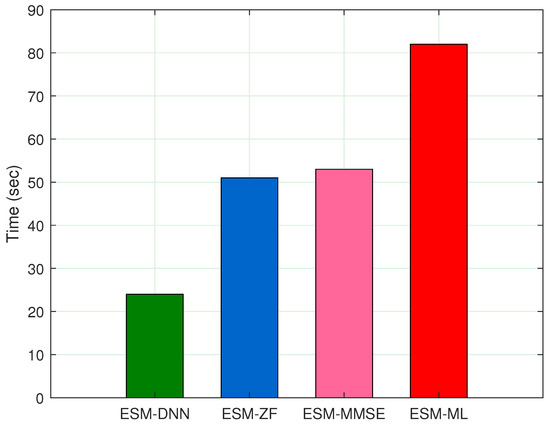

Figure 8 shows the computational time of B-DNN and other detection methods in ESM with QPSK under 2 × 2 antenna configuration case. It shows that the B-DNN method spends less time detecting the same number of symbols in comparison to conventional methods. Overall, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the feasibility of using the B-DNN method for signal detection in ESM.

Figure 8.

Computational time performanc of B-DNN in ESM with QPSK under MIMO system.

4.4. Separate DNN Signal Detector in GSM

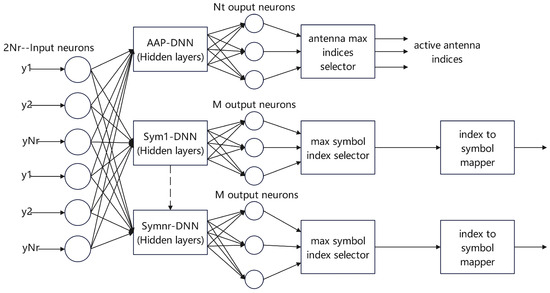

In [27], the authors proposed a new structure of DNN, in which they separate a single large DNN into sub-DNNs. As shown in Figure 9, one of these sub-DNNs is used to detect the antenna indices, while the remaining sub-DNNs are used to detect the symbols. Compared to a single large DNN, the parameters and complexity of this neural network are significantly decreased. Based on this approach, the training time of these sub-DNNs is shorter than that of a single large DNN. In addition, the authors considered a static/slow varying channel with a long coherence time so that the detector can be trained initially with the predefined, labeled training examples and then subsequently be used for signal detection. In addition to that, the input feature vector only includes real and imaginary parts of received signal instead of signal and channel matrix. In the training phase, activation functions are ReLU for hidden layers and softmax for output layers, and the optimizer is Adam, which speeds up the training process.

Figure 9.

System model of sub-DNN in GSM.

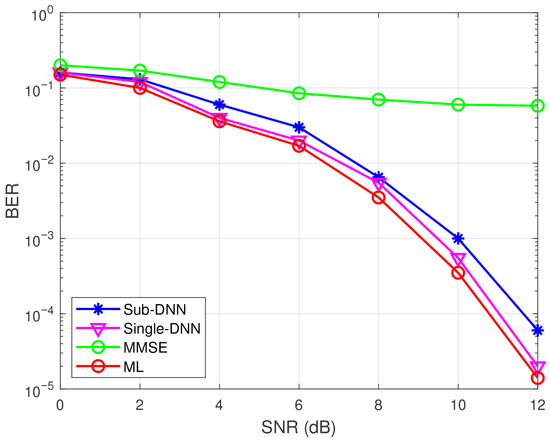

Figure 10 shows the BER performance of sub-DNN and other detection methods in GSM with BPSK under 4 × 2 antenna configuration case. It shows that the BER performance of the sub-DNNs cannot approach that of the single large DNN in static channel and Gaussian noise, although the gap between the two types of DNNs is small. Overall, this method can reduce the detection complexity, albeit at the cost of increasing BER. On the other hand, if the number of antennas increases, this method may become a good choice due to its low complexity and training time. Additionally, it tests some imperfect conditions, such as non-Gaussian noise and varying channels.

Figure 10.

BER performance of sub-DNN and other methods in GSM with BPSK under MIMO system.

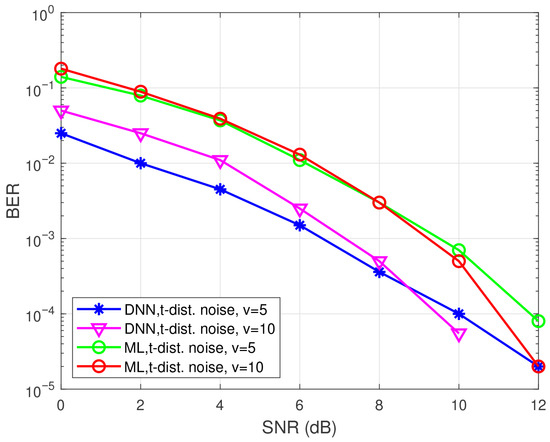

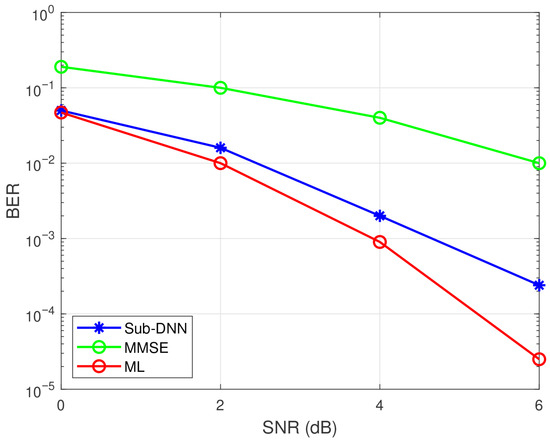

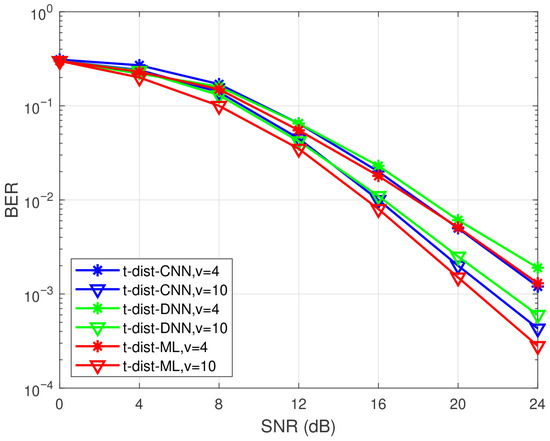

Figure 11 shows the BER performance of sub-DNN and other detection methods in GSM with BPSK and t-distributed noise under 4 × 4 antenna configuration case where v is the degrees of deviation from Gaussian. It shows that the BER performance of sub-DNN method in such noise condition outperforms the ML method. This is mainly because the ML detector is optimal when the noise is Gaussian-distributed and hence deviation from Gaussian distribution results in performance degradation. In addition to that, it also demonstrates that the DNN method is more effective in a non-Gaussian noise. Figure 12 shows the BER performance of sub-DNN and other detection methods in GSM with BPSK under a 16 × 10 antenna configuration case. It shows that the sub-DNN method can outperform the MMSE method and approach the ML method in low SNR with varying channels. In summary, this work presents an alternative approach by adjusting the architecture of the DNN, thereby achieving a delicate balance between BER and time complexity. Although the BER performance is slightly compromised, the significantly reduced training cost makes the DNN method feasible even when the number of antennas increases. At the same time, through simulating sub-DNN method and ML method in some imperfect conditions, the results demonstrate the feasibility of using DNN in these specific channel or noise environments.

Figure 11.

BER performance of sub-DNN in GSM with BPSK and t-distributed noise under MIMO system.

Figure 12.

BER performance of sub-DNN in GSM with BPSK and varying channel under MIMO system.

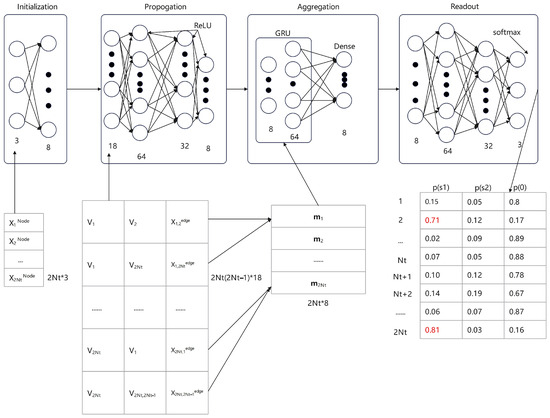

4.5. GNN Signal Detector in QSM

Graph neural networks (GNN) have garnered increasing attention in recent years, and these networks can be designed based on probabilistic models. In recent years, GNN-based detectors have been employed in MIMO systems [28,29,30]. In [31], the authors utilized this novel neural network for signal detection in QSM under Rayleigh fading channel with white Gaussian noise and Figure 13 shows the details of this neural network. Owing to the complex values in QSM, they employed an equivalent real-valued representation to ensure that all inputs to the neural network are real values. During the training phase, the network iteratively learns message-passing algorithms via propagation and aggregation modules, which utilize multilayer perceptron (MLP)-based message updates and gate recurrent unit (GRU)-based node feature updates, respectively. Finally, a readout module with MLP and Softmax outputs symbol probability distributions. In contrast to signal detectors in MIMO systems, the transmit signal vector in QSM is sparse. To address this issue, they proposed a regularized detection method applied after the training phase, which can reduce the detection complexity.

Figure 13.

System model of GNN signal detector in QSM.

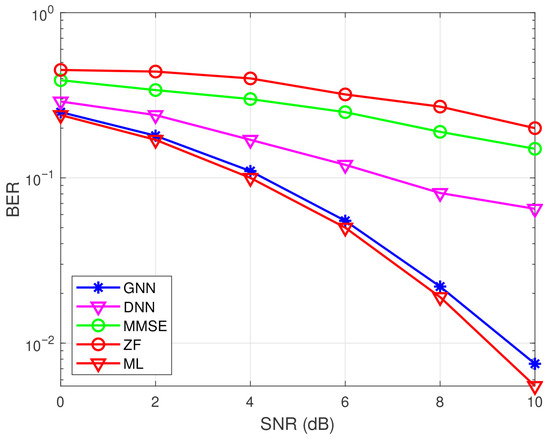

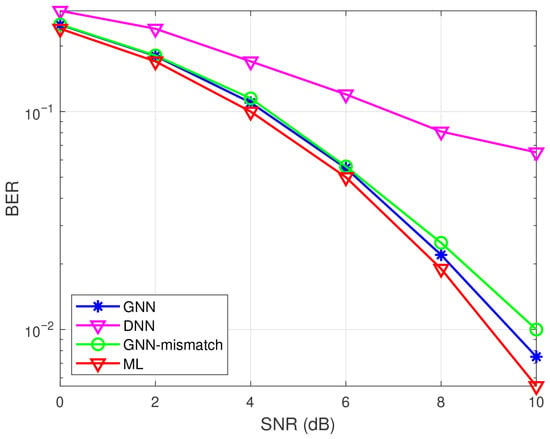

Figure 14 shows the BER performance of GNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under the 4 × 4 antenna configuration case. The simulation results of this GNN-based detector demonstrate that this method can approximately achieve the performance of the ML method in terms of BER, while it outperforms conventional DNN methods. Furthermore, the authors in [31] demonstrated the scalability of GNN in Figure 15 where two GNN models under and MIMO systems are trained and named as GNN-mismatch. After the training phase, this work also tested these GNN-mismatch models in a MIMO system. It shows that the GNN-mismatch method can approach the GNN method and ML method while it outperforms the DNN method. This demonstrates that a GNN-based detector trained under a specific antenna configuration can maintain acceptable BER performance with the same number of transmit antennas and a similar number of receive antennas. This proves its generalizability and potential for reducing training costs.

Figure 14.

BER performance of GNN and other detection methods in QSM with 4QAM under MIMO system.

Figure 15.

BER performance of GNN and mismatch-GNN in QSM with 4QAM under MIMO system.

In summary, the GNN constructs a probabilistic graphical model based on the Markov random field, mapping the signal detection problem into interactions between nodes (antennas) and edges (inter-symbol relationships). This explicit modeling enables the GNN to learn node dependencies through message-passing mechanisms, bypassing the reliance on flattened, fully connected architectures of DNNs. Additionally, compared to purely data-driven DNNs, the GNN achieves higher training efficiency with smaller data requirements, leveraging structured prior knowledge inherent to communication systems. In terms of the detection accuracy and scalability, it is clear that GNN has better performance than DNN.

4.6. CNN and DNN Signal Detector in DM-GSM

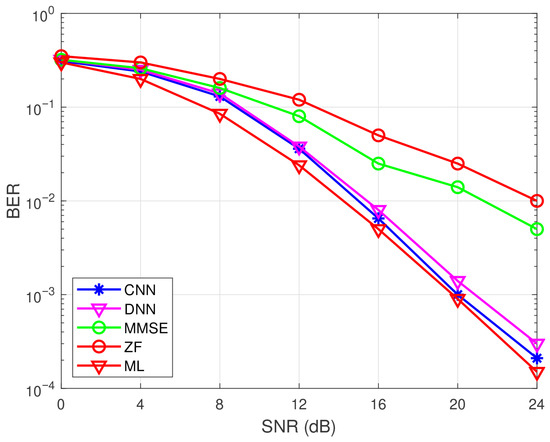

In the aforementioned section, we discussed the use of B-DNN and sub-DNN for signal detection in GSM. In [32], a dual-mode GSM (DM-GSM) was proposed. In traditional GSM, when two antennas are activated, they transmit the same symbol from a specific constellation. In contrast, in DM-GSM, it enhances spectral efficiency by partitioning transmit antennas into two groups that simultaneously transmit distinct constellation symbols (Mode A and B). In [33], the authors employed both DNN and CNN for signal detection in DM-GSM under static channel and white Gaussian noise while the constellation symbol is BPSK. This work employs a four-layer structure processing real/imaginary components of channel matrices and received signals through 256- and 128-node hidden layers with ReLU activation, while the CNN leverages convolutional layers (128 kernels) to extract spatial features from reshaped channel-signal matrices, followed by fully connected layers for bit prediction. Both models train offline on 400,000 symbols using Adam optimization (learning rate 0.0005) with binary cross-entropy loss function.

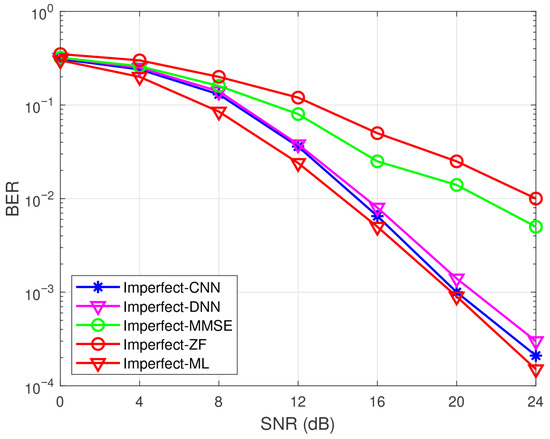

Figure 16 shows the BER performance of CNN, DNN and other detection methods in DM-GSM with BPSK under a 4 × 2 antenna configuration case. It shows that the CNN-based method achieves better BER performance than the DNN-based method in DM-GSM, and both CNN and DNN methods outperform MMSE and ZF in terms of BER. In terms of complexity, both DNN and CNN exhibit lower complexity than the ML method. Additionally, Figure 17 shows the BER performance of CNN, DNN, and other detection methods in DM-GSM with BPSK and imperfect CSI under a 4 × 2 antenna configuration case. It shows that the BER performance of CNN-based method outperforms the DNN and ZF MMSE methods while approaches the ML method in the high SNR region. Figure 18 shows the BER performance of CNN, DNN, and ML method in DM-GSM with BPSK and t-distributed noise under a 4 × 2 antenna configuration case. It shows that the BER performance of the CNN-based method outperforms the DNN method and approaches the ML method. Figure 17 and Figure 18 demonstrate the feasibility of using DL-based methods for signal detection in non-ideal environments.

Figure 16.

BER performance of CNN, DNN, and other detection methods in DM-GSM with BPSK under MIMO system.

Figure 17.

BER performance of CNN, DNN, and other detection methods in DM-GSM with BPSK and imperfect CSI under MIMO system.

Figure 18.

BER performance of CNN, DNN, and other detection methods in DM-GSM with BPSK and t-distributed noise under MIMO system.

4.7. DeepSM

In [34], the authors proposed a novel neural network to detect signals while estimating the CSI simultaneously. A key difficulty in prior studies is enabling neural network-based detectors to handle CSI variations over time-varying channels. To address this issue, they introduced a new DNN structure called DeepSM under a time-varying channel. The key innovation of the DeepSM architecture is its specific design for time-varying channels. In the training phase, unlike conventional approaches that use fixed initial channel estimates, DeepSM dynamically updates the CSI at each time slot through two parallel DNN subgroups. The detection subgroup processes the current received symbols, while the channel estimation subgroup incrementally refines the CSI using previous estimates and detection outputs. At the same time, mean-square error (MSE) as the loss function is used in the training phase while the activation function is ReLU and SGD is the optimizer. After the training phase, simulation results show that the BER performance of DeepSM method outperforms both the model-driven neural network method and the conventional DNN method in time-varying and non-linear channels. In Table 2, a comparison of the aforementioned DL-based signal detectors is provided.

Table 2.

Comprehensive comparison of DL-based signal detectors.

4.8. Summary of DL-Based Signal Detectors in SM

Based on above, a brief summary of these methods in various perspectives is given in this subsection. First, the seven discussed papers are categorized based on their neural network architectures. The authors in [22,25,26,27] primarily utilized feed-forward DNN as their core architecture. Among these, the authors in [22,26] employed B-DNN for GSM and ESM systems, while the authors in [27] decomposed the detection task into two sub-DNNs to reduce training complexity. In contrast, the authors in [22,33] implemented both DNN and CNN architectures for performance comparison. The authors in [31] adopted a novel structure called GNN, and the authors in [34] proposed a joint channel estimation and signal detection architecture called DeepSM to address CSI variations. Regarding simulation conditions, the authors in [27,34] incorporated time-varying channels, while the authors in [27,33,34] further investigated performance under non-ideal conditions, such as imperfect CSI and non-Gaussian noise. Overall, the works in [22,25,26] serve as benchmarks and achieve satisfactory BER performance with reasonable complexity under static channels and Gaussian noise. The authors in [27,33] explored CNNs, and their results generally indicate that CNNs are not a superior alternative in the DL-based signal detection area. Conversely, GNNs demonstrate strong performance, surpassing DNNs in training efficiency, BER, and generalization capability. Furthermore, the authors in [34] proposed a promising solution to the challenge of retraining under varying channel conditions. Overall, in terms of BER performance and training complexity, GNN outperforms feed-forward DNN and CNN in static channels and non-ideal environments. In varying channels, it is important to adapt to new channel conditions, and a new structure that combines channel estimation and signal detection can be considered as a promising solution.

5. Challenges in AI-Based Signal Detector

Despite the significant developments that have been achieved using DL to detect the signal in SM, in practical environments, this technique still faces several challenges.

5.1. Training Complexity of Neural Network

While DL-based signal detectors have shown promise in small-scale SM-MIMO systems, their training complexity becomes a critical bottleneck when scaling to massive MIMO configurations or high-order modulation schemes. For instance, in a 64 × 64 MIMO setup with 64-QAM, the input space of the neural detector explodes combinatorially, requiring millions of labeled channel realizations to achieve generalization. This challenge is exacerbated in SM, where the spatial constellation diagram introduces additional latent variables that further enlarge the hypothesis space. To mitigate this, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) [35] have recently been proposed to embed wireless domain knowledge into the training loss, reducing the complexity of the ray-tracing dataset. Alternatively, generative data augmentation via generative adversarial networks (GANs) [36] can synthesize realistic SM training samples by learning the joint distribution of channel matrices and antenna activation patterns. Future work may explore federated generative augmentation, where edge devices collaboratively train a shared GAN without exchanging raw RF data, thus preserving privacy while enriching the training set. Additionally, neural architecture search (NAS) can be specialized for SM by incorporating domain knowledge. A promising direction involves designing search spaces with attention layers that leverage antenna-group sparsity. This approach enables the automated design of low-complexity detectors that preserve BER performance.

5.2. Hardware Deployment Constraints

Meanwhile, the practical deployment of DL-based detectors in SM systems faces significant hardware constraints. Resource-constrained devices often struggle to support the computational overhead of deep neural networks, particularly in scenarios involving large-scale antenna arrays where real-time matrix operations and activation functions demand intensive parallel processing capabilities. Furthermore, the energy consumption of high-precision arithmetic units (e.g., FP32/FP64 GPUs) conflicts with the low-power requirements of wireless systems, which necessitates the adoption of quantization-aware training or binary neural networks approaches that typically compromise detection accuracy. Overall, current implementations of this emerging technology fail to strike a balance between detection performance and deployment feasibility, highlighting the need for further research to address these critical trade-offs.

5.3. Training Efficiency and Online Adaptation for Non-Stationary Channel

In SM systems, the performance of DL-based detectors heavily relies on training-time efficiency and online adaptability to non-stationary channels. The retraining cost, which includes computational overhead, latency, and data dependency, is a core bottleneck for practical deployment, especially on resource-constrained devices such as edge nodes or Internet of Things (IoT) terminals. Several recent works have targeted this problem and offered practical solutions. For instance, quantized neural networks (QNNs) [37] and knowledge distillation enable compact models that can be deployed on-device, although adaptation to non-stationary statistics remains challenging. To avoid catastrophic forgetting when new channel conditions appear, continual learning [38] methods allow incremental updates without full retraining. In the SM context, continual learning can adapt the detector to time-varying spatial correlations while preserving prior knowledge. Transfer learning [39] is another attractive option where the pre-trained model on historical or synthetic data is reused, and only the final layers are fine-tuned for the new scenario. For SM, this strategy can accelerate adaptation to any antenna configurations or noise environments. In summary, continual learning reduces retraining cost, but its effectiveness depends on the similarity between past and current CSI. Transfer learning is promising, yet it still requires further validation in SM-specific scenarios.

6. Comparison Between DL-Based Detectors and Conventional Detectors

Currently, DL-based signal detectors are not irreplaceable but coexist with conventional methods, effectively broadening the capabilities in this field rather than rendering existing approaches obsolete. Traditional detectors, such as ML, MMSE, and ZF, have clear mathematical derivations and physical interpretations, but also possess evident drawbacks. For instance, ZF is highly susceptible to noise, MMSE relies heavily on the accuracy of channel estimation, and ML suffers from high computational complexity. However, in many standard scenarios (e.g., static channels and Gaussian noise), well-designed traditional algorithms with low complexity (such as optimized approximate-ML algorithms) can compete effectively with DL detectors in terms of the overall performance trade-off between complexity and BER. The advantage of DL detectors lies in their non-linear mapping ability in handling more complex environments, such as non-ideal channel conditions and noise. Nevertheless, the training costs and limited versatility of DL detectors remain significant constraints. In the future, as related technologies advance and certain bottlenecks are resolved, a more likely scenario is that DL will no longer be used solely for signal detection. Instead, it will be applied jointly with other stages like channel estimation, coding, and modulation—a level of integration that would be unattainable by conventional approaches.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

SM is regarded as an innovation that has the potential to fundamentally increase spectral efficiency while maintaining the advantages and mitigating the disadvantages of MIMO schemes. DL is currently an emerging technology that has garnered a great deal of attention. Recently, significant progress has been made in using DL to improve the performance of signal detection in SM. Simulation results showed that DL-based detectors can achieve improvements in both BER and time complexity compared to conventional detectors.

In this article, we have reviewed and discussed recent advances in using DL for signal detection in SM and its variants. Although significant work has been conducted in this area, there is still much work to be conducted regarding the practicality of this technique. By analyzing the characteristics of different neural network structures and SM schemes, we have provided a comprehensive tutorial to guide detector design. In particular, we have shown the comparisons among different SM schemes and the neural networks used in these schemes. Finally, we have listed several challenges that can be future research directions in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J. and Y.P.; methodology, S.J. and Y.P.; software, S.J.; validation, S.J., Y.P.; formal analysis, S.J. and Y.P.; investigation, S.J.; resources, Y.P., F.A.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.P., F.A.-H.; visualization, S.J.; supervision, Y.P.; project administration, Y.P.; funding acquisition, Y.P., F.A.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau SAR (0085/2024/RIA2).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mesleh, R.; Haas, H.; Sinanovic, S.; Ahn, C.; Yun, S. Spatial modulation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2008, 4, 2228–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Serafimovski, N.; Mesleh, R.; Haas, H. Generalised spatial modulation. In Proceedings of the 44th Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 7–11 November 2010; pp. 1498–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Mesleh, R.; Ikki, S.; Aggoune, M. Quadrature spatial modulation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 6, 2738–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Sari, H.; Sezginer, S.; Ytu, S. Enhanced Spatial Modulation With Multiple Signal Constellations. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2015, 6, 2237–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, M.; Zeng, J.; Xiao, M. Offset Spatial Modulation and Offset Space Shift Keying: Efficient Designs for Single-RF MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2019, 8, 5434–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xiong, H.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C. Offset Spatial Modulation With Multiple Receive Antennas. IEEE Access 2020, 4, 100542–100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Cheng, X.; Wen, W.; Yang, Q.; Vincent, H.; Jiao, L. Differential Spatial Modulation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 7, 3262–3268. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Li, P.; Aissa, S.; Xia, H. Parallel Quadrature Spatial Modulation for Massive MIMO Systems With ICI Avoidance. IEEE Access 2019, 11, 154750–154760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Hudrouss, M.; El Astal, M.; Al Habbash, A.; Aissa, S. Signed Quadrature Spatial Modulation for MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 3, 2740–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, X.; Ju, Z. Generalized Spatial Modulation With Transmit Antenna Grouping for Massive MIMO. IEEE Access 2017, 11, 26798–26807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Zhang, K.; Mu, M. Antenna grouping assisted spatial modulation for massive MIMO systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP), Nanjin, China, 11–13 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, H.; Swindlehurst, L.; Haardt, M. Zero-Forcing Methods for Downlink Spatial Multiplexing in Multiuser MIMO Channels. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 2004, 2, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, M.; Madhow, U.; Verdu, S. Blind multiuser detection. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1995, 7, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, F.; Dan, L.; Yang, P.; Yin, L.; Xiang, W. Low-Complexity Signal Detection for Generalized Spatial Modulation. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2014, 3, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albreem, A.; Al Habbash, H.; Abu-Hudrouss, M.; EL Astal, T.A. Low-Complexity Detection Framework for Signed Quadrature Spatial Modulation Based on Approximated MMSE Sparse Detectors. IEEE Syst. J. 2025, 19, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Tong, F. An IRS-Aided GSSK Scheme for Wireless Communication System. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 6, 1398–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Sugiura, S.; Ng, S.; Hanzo, L. Spatial modulation and space-time shift keying: Optimal performance at a reduced detection complexity. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2013, 1, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, P.; Yu, Q.; Li, S. A new low-complexity near-ML detection algorithm for spatial modulation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2013, 2, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, S.; Xu, C.; Ng, S.; Hanzo, L. Reduced-complexity iterative-detection aided generalized space-time shift keying. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2012, 8, 3656–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Fan, S.; Di Renzo, M.; Xiang, W.; Li, S. Efficient compressive sensing detectors for generalized spatial modulation systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 2, 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C. Low-Complexity Near-Optimal Demodulation for Spatial Modulation Based on M-Algorithm. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2025, 3, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsaid, H.; Singh, K.; Biswas, S.; Li, C.P.; Alouini, M.S. Block deep neural network-based signal detector for generalized spatial modulation. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 12, 2775–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorot, X.; Bordes, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep sparse rectifier neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 11–13 April 2011; pp. 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.; Hoydis, J. An introduction to deep learning for the physical layer. IEEE Trans. Cognit. Commun. Netw. 2017, 12, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.; Peng, Y.; AL-Hazemi, F. Deep Learning Based Signal Detection for Quadrature Spatial Modulation System. China Commun. 2024, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Peng, Y.; AL-Hazemi, F.; Mohammad, M. Signal Detection for Enhanced Spatial Modulation Based Communication: A Block Deep Neural Network Approach. Mathematics 2025, 1, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamasundar, B.; Chockalingam, A. A DNN Architecture for the Detection of Generalized Spatial Modulation Signals. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 12, 2770–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, A.; Moghadam, N.; Liu, D.; Gafvert, K.; Huang, J. Graph neural networks for massive MIMO detection. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 12–18 July 2020; pp. 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.; Kosasih, A.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Hardjawana, W.; Letaief, K. GNN-Enhanced Approximate Message Passing for Massive/Ultra-Massive MIMO Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Glasgow, UK, 26–29 March 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kosasih, A.; Onasis, V.; Miloslavskaya, V.; Hardjawana, W.; Andrean, V.; Vucetic, B. Graph Neural Network Aided MU-MIMO Detectors. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 9, 2540–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Deng, Y. Graph Neural Network Based Signal Detection in Quadrature Spatial Modulation System. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE the 23rd International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Nanjing, China, 20–22 October 2023; pp. 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Jeyachitra, R. Dual-Mode Generalized Spatial Modulation MIMO for Visible Light Communications. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2018, 2, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, M.; Pang, K.; Hao, H. Deep Learning Based Signal Detection in Dual Mode Generalized Spatial Modulation. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Barcelona, Spain, 5–8 July 2022; pp. 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, P.; Liu, S.; Luong, W.; Maunder, G.; Yang, L.; Hanzo, L. Deep-Learning-Aided Joint Channel Estimation and Data Detection for Spatial Modulation. IEEE Access 2020, 11, 191910–191919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 2, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montréal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Hubara, I.; Courbariaux, M.; Soudry, D.; El-Yaniv, R.; Bengio, Y. Quantized neural networks: Training neural networks with low precision weights and activations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 3, 3521–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. Proc. IEEE 2020, 7, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).