Univariate Linear Normal Models: Optimal Equivariant Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Equivariant Estimators for Linear Models

3. Minimum Riemannian Risk Estimators

4. Numerical Evaluation

5. Conclusions

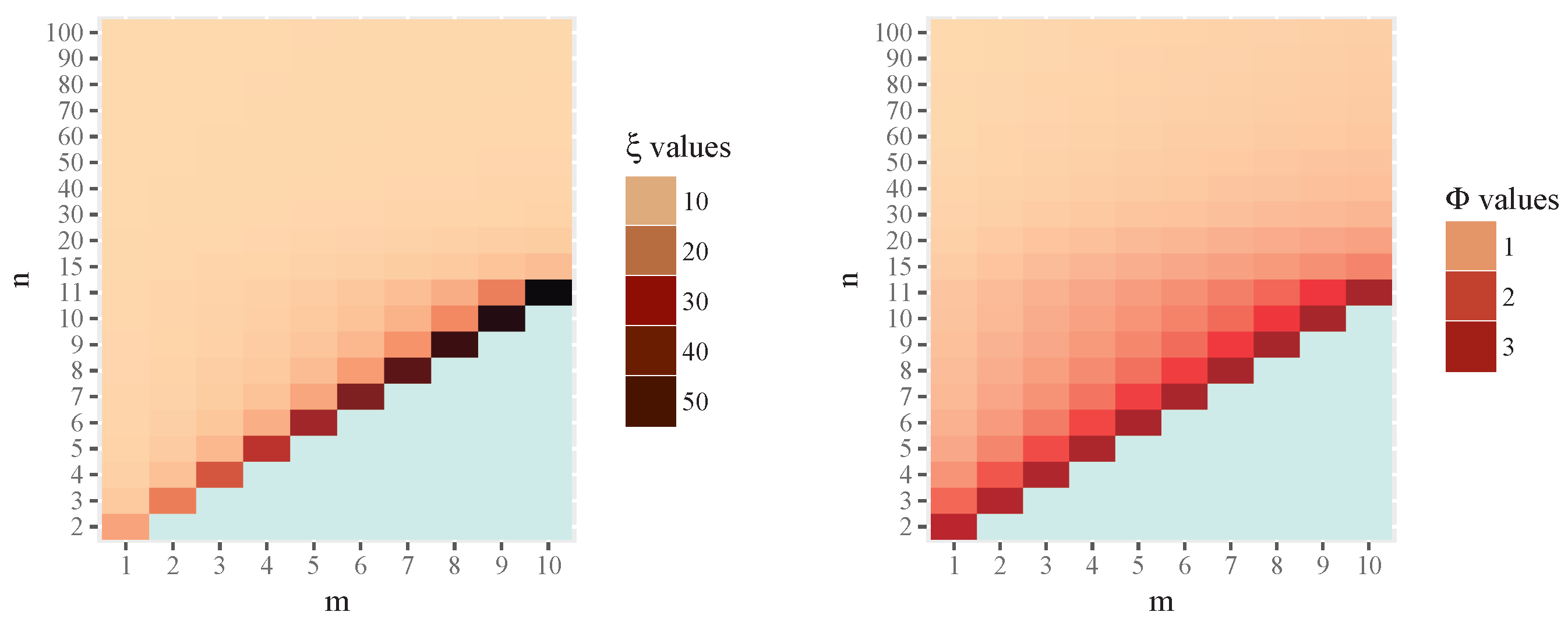

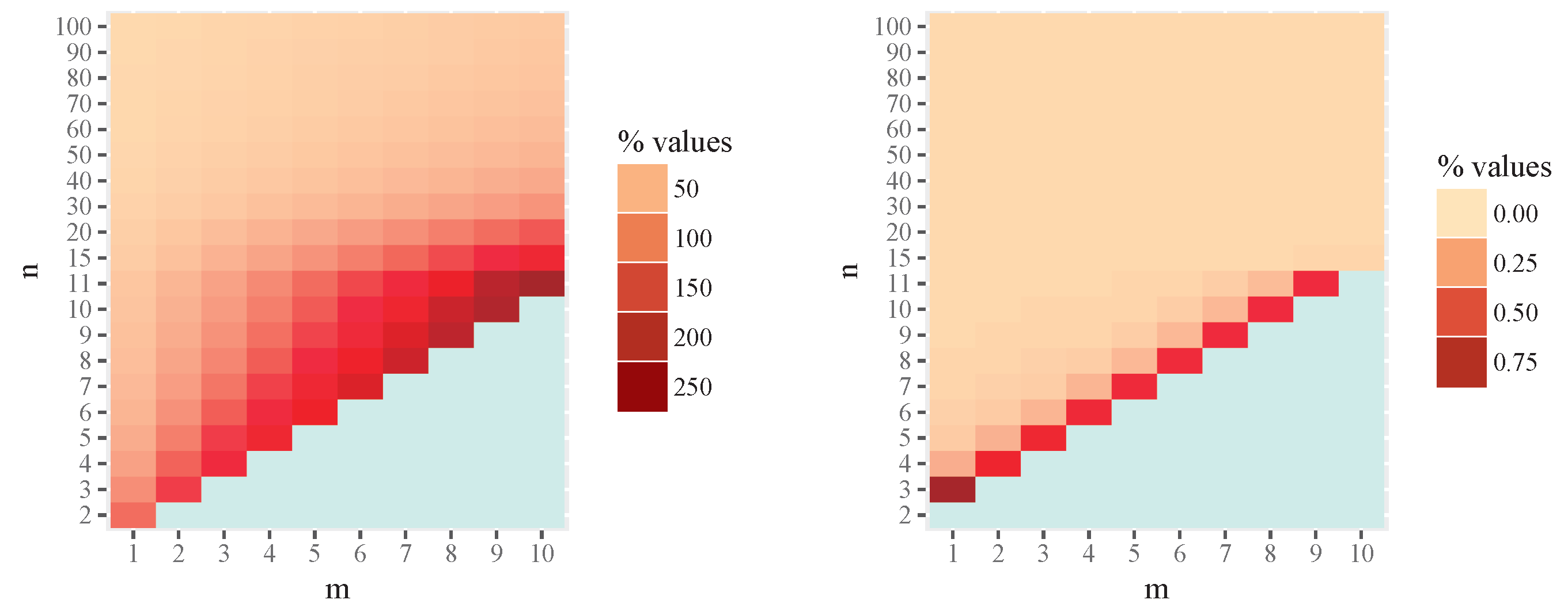

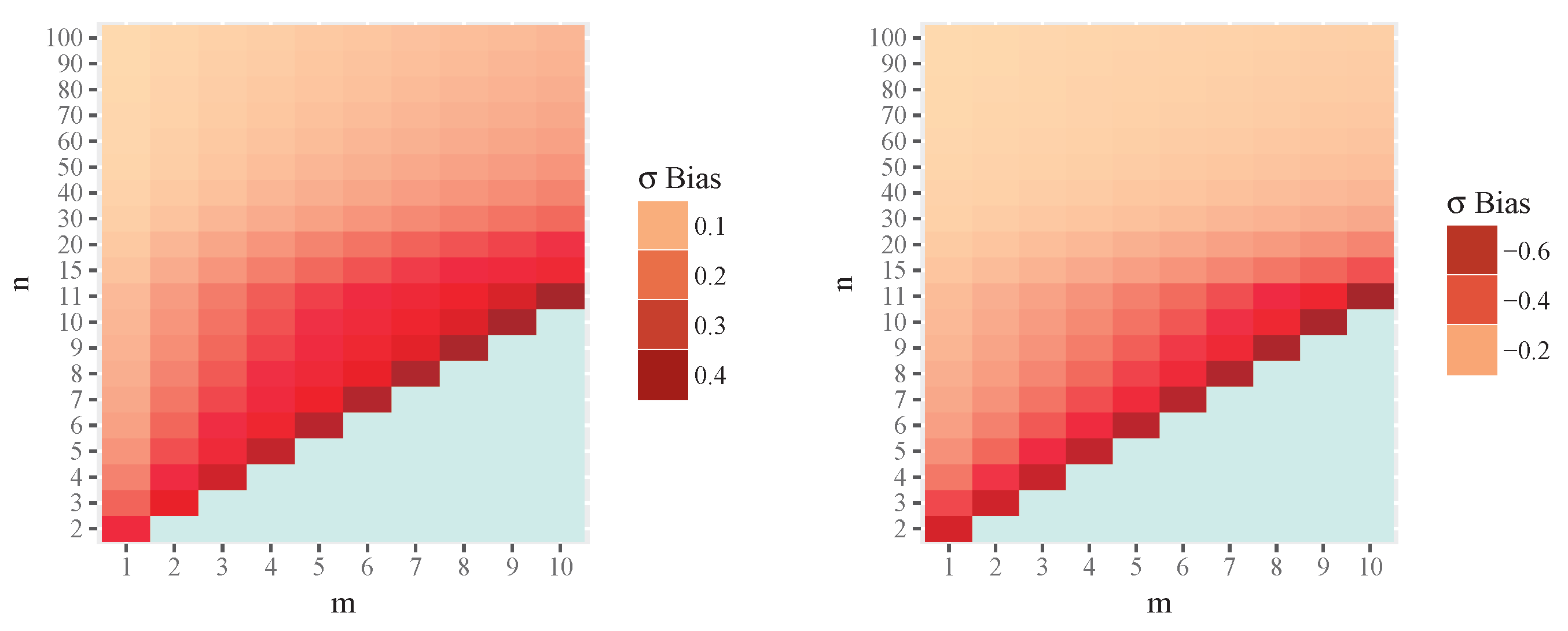

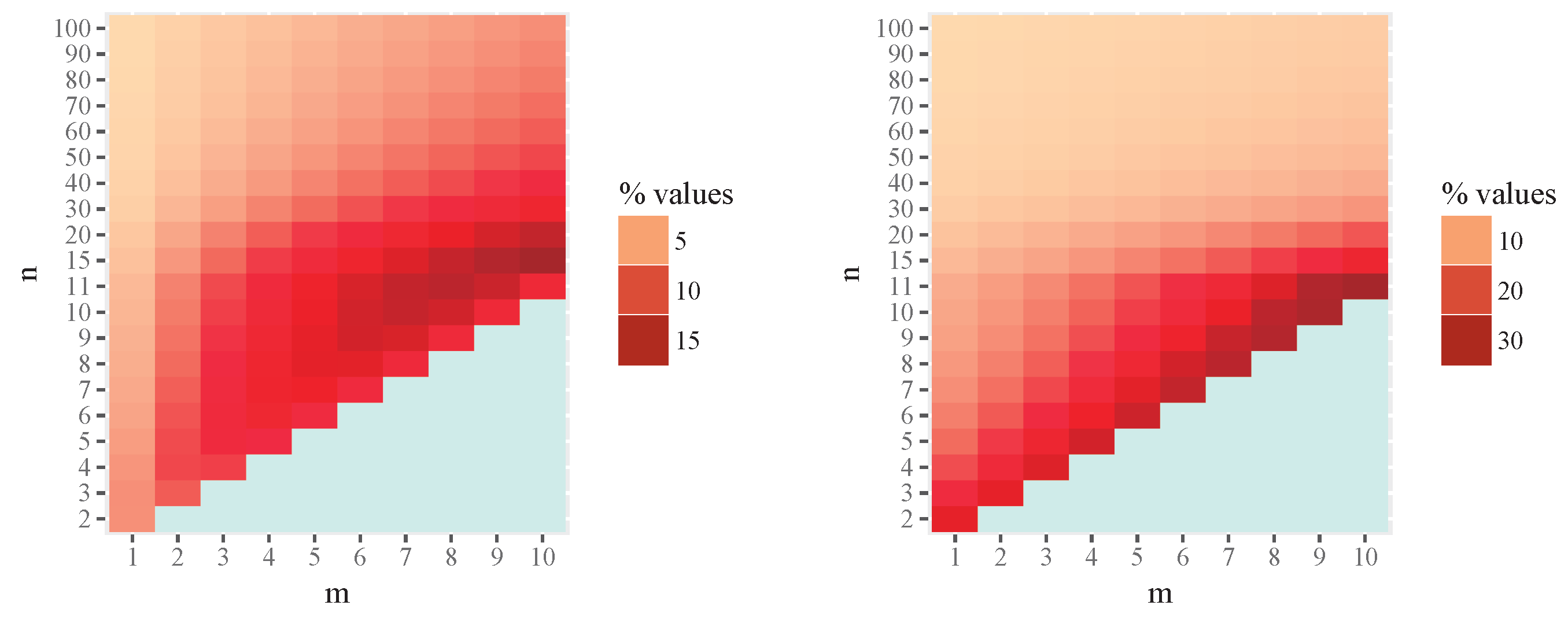

- The intrinsic risk and bias of the MLE can be substantially larger than those of the MIRE in small-sample settings.

- The difference between the two estimators decreases as the sample size increases.

- The approximate estimator (a-MIRE) provides a practical and computationally efficient alternative, achieving intrinsic risk values nearly identical to those of the MIRE for moderate sample sizes.

Future Research Directions

- Extension to heteroscedastic or correlated error structures, where the geometry of the model may differ significantly.

- Intrinsic Bayesian formulations based on noninformative or reference priors, where posterior summaries may be interpreted in geometric terms.

- Computational schemes for approximating the Rao distance efficiently in high-dimensional or large-sample contexts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8.66992 3.03876 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 3.07654 1.16322 | 13.85950 3.22626 | |||||||||

| 4 | 2.15828 0.71941 | 4.40442 1.32989 | 19.07110 3.31958 | ||||||||

| 5 | 1.79608 0.52257 | 2.87441 0.86369 | 5.72625 1.42579 | 24.29080 3.37544 | |||||||

| 6 | 1.60525 0.41144 | 2.28365 0.65040 | 3.59243 0.95721 | 7.05039 1.48877 | 29.51720 3.41264 | ||||||

| 7 | 1.48787 0.33979 | 1.97404 0.52570 | 2.77223 0.73918 | 4.31144 1.02277 | 8.37564 1.53330 | 34.74390 3.43918 | |||||

| 8 | 1.40849 0.28964 | 1.78417 0.44287 | 2.34344 0.60912 | 3.26141 0.80445 | 5.03105 1.07128 | 9.70161 1.56646 | 39.97520 3.45908 | ||||

| 9 | 1.35126 0.25252 | 1.65604 0.38342 | 2.08088 0.52102 | 2.71323 0.67272 | 3.75096 0.85446 | 5.75096 1.10863 | 11.02800 1.59210 | 45.20590 3.47455 | |||

| 10 | 1.30807 0.22391 | 1.56381 0.33847 | 1.90388 0.45665 | 2.37787 0.58233 | 3.08328 0.72281 | 4.24078 0.89402 | 6.47135 1.13827 | 12.35490 1.61252 | 50.43540 3.48692 | ||

| 11 | 1.27433 0.20116 | 1.49427 0.30320 | 1.77656 0.40721 | 2.15190 0.51544 | 2.67503 0.63172 | 3.45350 0.76331 | 4.73076 0.92608 | 7.19181 1.16237 | 13.68190 1.62918 | 55.65840 3.49704 | |

| 15 | 1.19071 0.14318 | 1.33089 0.21469 | 1.49647 0.28618 | 1.69505 0.35810 | 1.93754 0.43107 | 2.24025 0.50594 | 2.62870 0.58406 | 3.14513 0.66756 | 3.86473 0.76019 | 4.93543 0.86917 | |

| 20 | 1.13807 0.10534 | 1.23410 0.15768 | 1.34212 0.20973 | 1.46452 0.26160 | 1.60436 0.31342 | 1.76568 0.36539 | 1.95380 0.41771 | 2.17599 0.47070 | 2.44246 0.52476 | 2.76780 0.58046 | |

| 30 | 1.08895 0.06895 | 1.14768 0.10318 | 1.21093 0.13718 | 1.27923 0.17097 | 1.35322 0.20457 | 1.43364 0.23801 | 1.52137 0.27132 | 1.61744 0.30453 | 1.72312 0.33769 | 1.83991 0.37084 | |

| 40 | 1.06561 0.05126 | 1.10786 0.07673 | 1.15245 0.10205 | 1.19960 0.12721 | 1.24952 0.15224 | 1.30246 0.17713 | 1.35872 0.20191 | 1.41860 0.22657 | 1.48247 0.25114 | 1.55075 0.27561 | |

| 50 | 1.05197 0.04080 | 1.08495 0.06108 | 1.11936 0.08126 | 1.15532 0.10134 | 1.19289 0.12131 | 1.23222 0.14119 | 1.27342 0.16098 | 1.31663 0.18068 | 1.36200 0.20029 | 1.40970 0.21983 | |

| 60 | 1.04303 0.03388 | 1.07007 0.05074 | 1.09808 0.06752 | 1.12711 0.08423 | 1.15722 0.10086 | 1.18846 0.11742 | 1.22090 0.13391 | 1.25461 0.15033 | 1.28967 0.16669 | 1.32617 0.18298 | |

| 70 | 1.03671 0.02897 | 1.05963 0.04340 | 1.08324 0.05776 | 1.10757 0.07207 | 1.13268 0.08632 | 1.15857 0.10051 | 1.18530 0.11466 | 1.21291 0.12874 | 1.24144 0.14278 | 1.27093 0.15676 | |

| 80 | 1.03201 0.02531 | 1.05189 0.03791 | 1.07230 0.05047 | 1.09324 0.06298 | 1.11476 0.07545 | 1.13687 0.08787 | 1.15959 0.10025 | 1.18295 0.11259 | 1.20697 0.12489 | 1.23170 0.13715 | |

| 90 | 1.02838 0.02246 | 1.04593 0.03366 | 1.06390 0.04481 | 1.08228 0.05593 | 1.10111 0.06701 | 1.12039 0.07806 | 1.14014 0.08907 | 1.16038 0.10005 | 1.18112 0.11099 | 1.20239 0.12190 | |

| 100 | 1.02548 0.02020 | 1.04120 0.03026 | 1.05725 0.04029 | 1.07363 0.05030 | 1.09036 0.06027 | 1.10745 0.07022 | 1.12492 0.08014 | 1.14276 0.09002 | 1.16101 0.09988 | 1.17966 0.10972 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 80.54 – | ||||||||||

| 3 | 57.08 0.95 | 114.18 – | |||||||||

| 4 | 42.51 0.12 | 87.63 0.64 | 140.61 – | ||||||||

| 5 | 33.73 0.04 | 67.93 0.11 | 114.44 0.61 | 162.61 – | |||||||

| 6 | 27.88 0.02 | 54.83 0.04 | 90.96 0.10 | 138.22 0.58 | 181.58 – | ||||||

| 7 | 23.72 0.01 | 45.78 0.02 | 74.42 0.03 | 112.04 0.10 | 159.65 0.56 | 198.31 – | |||||

| 8 | 20.63 0.01 | 39.22 0.01 | 62.67 0.02 | 92.70 0.03 | 131.51 0.09 | 179.21 0.55 | 213.33 – | ||||

| 9 | 18.25 0.00 | 34.27 0.01 | 54.00 0.01 | 78.62 0.01 | 109.84 0.03 | 149.62 0.09 | 197.26 0.54 | 226.98 – | |||

| 10 | 16.35 0.00 | 30.42 0.00 | 47.38 0.01 | 68.08 0.01 | 93.73 0.01 | 125.99 0.03 | 166.59 0.09 | 214.02 0.53 | 239.51 – | ||

| 11 | 14.81 0.00 | 27.33 0.00 | 42.19 0.00 | 59.96 0.00 | 81.53 0.01 | 108.10 0.01 | 141.27 0.03 | 182.58 0.08 | 229.71 0.53 | 251.10 – | |

| 15 | 10.75 0.00 | 19.42 0.00 | 29.26 0.00 | 40.45 0.00 | 53.25 0.00 | 68.04 0.00 | 85.30 0.00 | 105.68 0.00 | 130.06 0.01 | 159.58 0.01 | |

| 20 | 8.00 0.00 | 14.25 0.00 | 21.13 0.00 | 28.68 0.00 | 37.01 0.00 | 46.24 0.00 | 56.51 0.00 | 68.00 0.00 | 80.96 0.00 | 95.69 0.00 | |

| 30 | 5.29 0.00 | 9.29 0.00 | 13.56 0.00 | 18.11 0.00 | 22.95 0.00 | 28.11 0.00 | 33.63 0.00 | 39.52 0.00 | 45.85 0.00 | 52.66 0.00 | |

| 40 | 3.96 0.00 | 6.89 0.00 | 9.98 0.00 | 13.23 0.00 | 16.62 0.00 | 20.18 0.00 | 23.91 0.00 | 27.83 0.00 | 31.95 0.00 | 36.28 0.00 | |

| 50 | 3.16 0.00 | 5.48 0.00 | 7.90 0.00 | 10.42 0.00 | 13.03 0.00 | 15.74 0.00 | 18.55 0.00 | 21.47 0.00 | 24.51 0.00 | 27.67 0.00 | |

| 60 | 2.63 0.00 | 4.54 0.00 | 6.54 0.00 | 8.59 0.00 | 10.71 0.00 | 12.90 0.00 | 15.15 0.00 | 17.48 0.00 | 19.88 0.00 | 22.35 0.00 | |

| 70 | 2.25 0.00 | 3.88 0.00 | 5.57 0.00 | 7.31 0.00 | 9.09 0.00 | 10.93 0.00 | 12.81 0.00 | 14.74 0.00 | 16.72 0.00 | 18.75 0.00 | |

| 80 | 1.97 0.00 | 3.39 0.00 | 4.86 0.00 | 6.36 0.00 | 7.90 0.00 | 9.48 0.00 | 11.09 0.00 | 12.74 0.00 | 14.42 0.00 | 16.15 0.00 | |

| 90 | 1.75 0.00 | 3.01 0.00 | 4.30 0.00 | 5.63 0.00 | 6.99 0.00 | 8.37 0.00 | 9.78 0.00 | 11.22 0.00 | 12.68 0.00 | 14.18 0.00 | |

| 100 | 1.57 0.00 | 2.70 0.00 | 3.86 0.00 | 5.05 0.00 | 6.26 0.00 | 7.49 0.00 | 8.74 0.00 | 10.02 0.00 | 11.32 0.00 | 12.64 0.00 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.25273 −0.64316 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 0.15729 −0.34089 | 0.33352 −0.66450 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.11879 −0.23333 | 0.23107 −0.38021 | 0.37337 −0.68608 | ||||||||

| 5 | 0.09542 −0.17763 | 0.18380 −0.27128 | 0.27237 −0.41182 | 0.39710 −0.70605 | |||||||

| 6 | 0.07989 −0.14348 | 0.15393 −0.21196 | 0.22483 −0.30232 | 0.29910 −0.43827 | 0.41288 −0.72422 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.06877 −0.12037 | 0.13280 −0.17426 | 0.19348 −0.24073 | 0.25307 −0.32857 | 0.31782 −0.46104 | 0.42409 −0.74076 | |||||

| 8 | 0.06039 −0.10369 | 0.11693 −0.14809 | 0.17044 −0.20063 | 0.22201 −0.26549 | 0.27371 −0.35132 | 0.33165 −0.48102 | 0.43251 −0.75589 | ||||

| 9 | 0.05384 −0.09107 | 0.10451 −0.12881 | 0.15255 −0.17224 | 0.19859 −0.22366 | 0.24357 −0.28719 | 0.28944 −0.37137 | 0.34228 −0.49884 | 0.43904 −0.76980 | |||

| 10 | 0.04858 −0.08120 | 0.09451 −0.11401 | 0.13817 −0.15101 | 0.17997 −0.19362 | 0.22044 −0.24409 | 0.26044 −0.30651 | 0.30184 −0.38931 | 0.35073 −0.51492 | 0.44424 −0.78265 | ||

| 11 | 0.04426 −0.07326 | 0.08628 −0.10227 | 0.12633 −0.13451 | 0.16471 −0.17089 | 0.20175 −0.21278 | 0.23791 −0.26244 | 0.27399 −0.32390 | 0.31186 −0.40554 | 0.35758 −0.52956 | 0.44844 −0.79460 | |

| 15 | 0.03267 −0.05266 | 0.06405 −0.07250 | 0.09426 −0.09377 | 0.12339 −0.11673 | 0.15156 −0.14172 | 0.17887 −0.16918 | 0.20545 −0.19972 | 0.23144 −0.23423 | 0.25707 −0.27404 | 0.28272 −0.32133 | |

| 20 | 0.02461 −0.03897 | 0.04848 −0.05318 | 0.07164 −0.06810 | 0.09414 −0.08383 | 0.11602 −0.10047 | 0.13732 −0.11814 | 0.15809 −0.13700 | 0.17836 −0.15724 | 0.19818 −0.17912 | 0.21761 −0.20294 | |

| 30 | 0.01649 −0.02564 | 0.03264 −0.03470 | 0.04845 −0.04405 | 0.06394 −0.05370 | 0.07913 −0.06368 | 0.09403 −0.07402 | 0.10864 −0.08474 | 0.12298 −0.09588 | 0.13707 −0.10748 | 0.15090 −0.11958 | |

| 40 | 0.01240 −0.01911 | 0.02460 −0.02576 | 0.03661 −0.03256 | 0.04843 −0.03953 | 0.06008 −0.04666 | 0.07154 −0.05397 | 0.08284 −0.06146 | 0.09397 −0.06916 | 0.10495 −0.07707 | 0.11576 −0.08520 | |

| 50 | 0.00994 −0.01523 | 0.01974 −0.02048 | 0.02942 −0.02583 | 0.03899 −0.03128 | 0.04843 −0.03682 | 0.05775 −0.04248 | 0.06696 −0.04824 | 0.07606 −0.05413 | 0.08506 −0.06013 | 0.09394 −0.06626 | |

| 60 | 0.00829 −0.01266 | 0.01649 −0.01700 | 0.02460 −0.02141 | 0.03262 −0.02588 | 0.04056 −0.03042 | 0.04842 −0.03503 | 0.05620 −0.03971 | 0.06390 −0.04447 | 0.07152 −0.04931 | 0.07906 −0.05423 | |

| 70 | 0.00711 −0.01083 | 0.01415 −0.01453 | 0.02113 −0.01827 | 0.02805 −0.02207 | 0.03490 −0.02591 | 0.04169 −0.02980 | 0.04842 −0.03375 | 0.05509 −0.03775 | 0.06170 −0.04180 | 0.06825 −0.04591 | |

| 80 | 0.00622 −0.00946 | 0.01240 −0.01269 | 0.01852 −0.01594 | 0.02460 −0.01924 | 0.03062 −0.02257 | 0.03660 −0.02594 | 0.04253 −0.02934 | 0.04842 −0.03279 | 0.05425 −0.03628 | 0.06005 −0.03981 | |

| 90 | 0.00554 −0.00840 | 0.01103 −0.01126 | 0.01649 −0.01414 | 0.02190 −0.01705 | 0.02728 −0.01999 | 0.03262 −0.02296 | 0.03792 −0.02595 | 0.04319 −0.02898 | 0.04841 −0.03204 | 0.05360 −0.03514 | |

| 100 | 0.00498 −0.00756 | 0.00993 −0.01012 | 0.01485 −0.01270 | 0.01974 −0.01531 | 0.02459 −0.01794 | 0.02942 −0.02059 | 0.03421 −0.02327 | 0.03898 −0.02597 | 0.04371 −0.02870 | 0.04841 −0.03145 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4.20 27.23 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 4.25 19.98 | 6.90 27.37 | |||||||||

| 4 | 3.92 15.14 | 8.03 21.74 | 8.40 28.36 | ||||||||

| 5 | 3.48 12.08 | 7.82 17.04 | 10.41 23.79 | 9.34 29.54 | |||||||

| 6 | 3.10 10.01 | 7.29 13.81 | 10.56 19.10 | 12.02 25.80 | 9.99 30.74 | ||||||

| 7 | 2.78 8.53 | 6.71 11.55 | 10.13 15.68 | 12.52 21.11 | 13.18 27.73 | 10.46 31.91 | |||||

| 8 | 2.52 7.42 | 6.17 9.90 | 9.54 13.22 | 12.25 17.52 | 13.99 23.04 | 14.04 29.54 | 10.82 33.04 | ||||

| 9 | 2.30 6.57 | 5.70 8.66 | 8.93 11.39 | 11.72 14.87 | 13.89 19.31 | 15.11 24.88 | 14.72 31.26 | 11.10 34.11 | |||

| 10 | 2.11 5.89 | 5.28 7.68 | 8.36 9.99 | 11.12 12.88 | 13.45 16.49 | 15.17 21.02 | 16.01 26.63 | 15.26 32.88 | 11.32 35.13 | ||

| 11 | 1.95 5.34 | 4.91 6.90 | 7.84 8.89 | 10.53 11.33 | 12.89 14.33 | 14.83 18.05 | 16.21 22.66 | 16.73 28.30 | 15.70 34.43 | 11.50 36.11 | |

| 15 | 1.49 3.87 | 3.82 4.90 | 6.21 6.14 | 8.50 7.61 | 10.66 9.32 | 12.65 11.31 | 14.45 13.66 | 16.05 16.44 | 17.39 19.76 | 18.39 23.76 | |

| 20 | 1.15 2.88 | 2.98 3.59 | 4.89 4.42 | 6.78 5.37 | 8.59 6.44 | 10.32 7.64 | 11.97 8.99 | 13.52 10.51 | 14.97 12.23 | 16.32 14.19 | |

| 30 | 0.79 1.91 | 2.06 2.33 | 3.42 2.83 | 4.78 3.37 | 6.12 3.96 | 7.43 4.60 | 8.70 5.29 | 9.93 6.04 | 11.13 6.84 | 12.28 7.71 | |

| 40 | 0.60 1.42 | 1.58 1.73 | 2.63 2.08 | 3.69 2.46 | 4.74 2.86 | 5.78 3.29 | 6.80 3.74 | 7.80 4.22 | 8.77 4.73 | 9.72 5.27 | |

| 50 | 0.48 1.14 | 1.28 1.37 | 2.13 1.64 | 3.00 1.93 | 3.87 2.24 | 4.72 2.56 | 5.57 2.89 | 6.40 3.24 | 7.22 3.61 | 8.03 3.99 | |

| 60 | 0.41 0.95 | 1.07 1.14 | 1.79 1.36 | 2.53 1.59 | 3.26 1.83 | 3.99 2.09 | 4.72 2.36 | 5.43 2.63 | 6.14 2.92 | 6.83 3.21 | |

| 70 | 0.35 0.81 | 0.92 0.97 | 1.55 1.16 | 2.18 1.35 | 2.82 1.56 | 3.46 1.77 | 4.09 1.99 | 4.71 2.21 | 5.33 2.45 | 5.94 2.69 | |

| 80 | 0.31 0.71 | 0.81 0.85 | 1.36 1.01 | 1.92 1.18 | 2.49 1.35 | 3.05 1.53 | 3.61 1.72 | 4.16 1.91 | 4.71 2.11 | 5.26 2.31 | |

| 90 | 0.27 0.63 | 0.72 0.75 | 1.21 0.89 | 1.72 1.04 | 2.22 1.19 | 2.73 1.35 | 3.23 1.51 | 3.73 1.68 | 4.22 1.85 | 4.71 2.03 | |

| 100 | 0.25 0.57 | 0.65 0.68 | 1.10 0.80 | 1.55 0.93 | 2.01 1.07 | 2.47 1.21 | 2.92 1.35 | 3.37 1.50 | 3.83 1.65 | 4.27 1.80 | |

References

- Park, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, M. Robust explicit estimators using the power-weighted repeated medians. J. Appl. Stat. 2023, 51, 1590–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, K.; Terada, Y.; Kim, J.K. Semiparametric adaptive estimation under informative sampling. Ann. Stat. 2025, 53, 1347–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. Asymptotic distribution of maximum likelihood estimator in generalized linear mixed models with crossed random effects. Ann. Stat. 2025, 53, 1298–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C. Information and accuracy attainable in the estimation of statistical parameters. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 1945, 37, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Burbea, J.; Rao, C. Entropy differential metric, distance and divergence measures in probability spaces: A unified approach. J. Multivar. Anal. 1982, 12, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbea, J. Informative geometry of probability spaces. Expo. Math. 1986, 4, 347–378. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.; Nagaoka, H. Methods of Information Geometry; American Mathematical Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, J.; Corcuera, J. Intrinsic Analysis of the Statistical Estimation. Ann. Stat. 1995, 23, 1562–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Oller, J. What does intrinsic mean in statistical estimation? Sort 2006, 2, 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Casas, D.; Oller, J. Variational Information Principles to Unveil Physical Laws. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, J.; Juárez, M. Intrinsic estimation. In Bayesian Statistics 7; Bernardo, J., Bayarri, M., Berger, J., Dawid, A., Hackerman, W., Smith, A., West, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, J.M.; Corcuera, J.M. Intrinsic Bayesian Estimation Using the Kullback–Leibler Divergence. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 2003, 55, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, E.; Casella, G. Theory of Point Estimation; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Amari, S.I. Information Geometry and Its Applications; Applied Mathematical Sciences; Springer Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; Volume 194. [Google Scholar]

- Ay, N.; Jost, J.; Lê, H.V.; Schwachhöfer, L. Information Geometry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, F. An Elementary Introduction to Information Geometry. Entropy 2020, 22, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbea, J.; Oller, J.M. The information metric for univariate linear elliptic models. Stat. Risk Model. 1988, 6, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, E. A general concept of unbiasedness. Ann. Math. Stat. 1951, 22, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcher, H. Riemannian Center of Mass and Mollifier Smoothing. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1977, 30, 509–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram Research, Inc. Mathematica, Version 10.2, Wolfram Research, Inc.: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.wolfram.com/mathematica/ (accessed on 1 July 2016).

- Gelman, A.; Pasarica, C.; Dodhia, R. Let’s practice what we preach: Turning tables into graphs. Am. Stat. 2002, 56, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García, G.; Cubedo, M.; Oller, J.M. Univariate Linear Normal Models: Optimal Equivariant Estimation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223659

García G, Cubedo M, Oller JM. Univariate Linear Normal Models: Optimal Equivariant Estimation. Mathematics. 2025; 13(22):3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223659

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía, Gloria, Marta Cubedo, and Josep M. Oller. 2025. "Univariate Linear Normal Models: Optimal Equivariant Estimation" Mathematics 13, no. 22: 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223659

APA StyleGarcía, G., Cubedo, M., & Oller, J. M. (2025). Univariate Linear Normal Models: Optimal Equivariant Estimation. Mathematics, 13(22), 3659. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223659