A Fermatean Fuzzy Game-Theoretic Framework for Policy Design in Sustainable Health Supply Chains

Abstract

1. Introduction

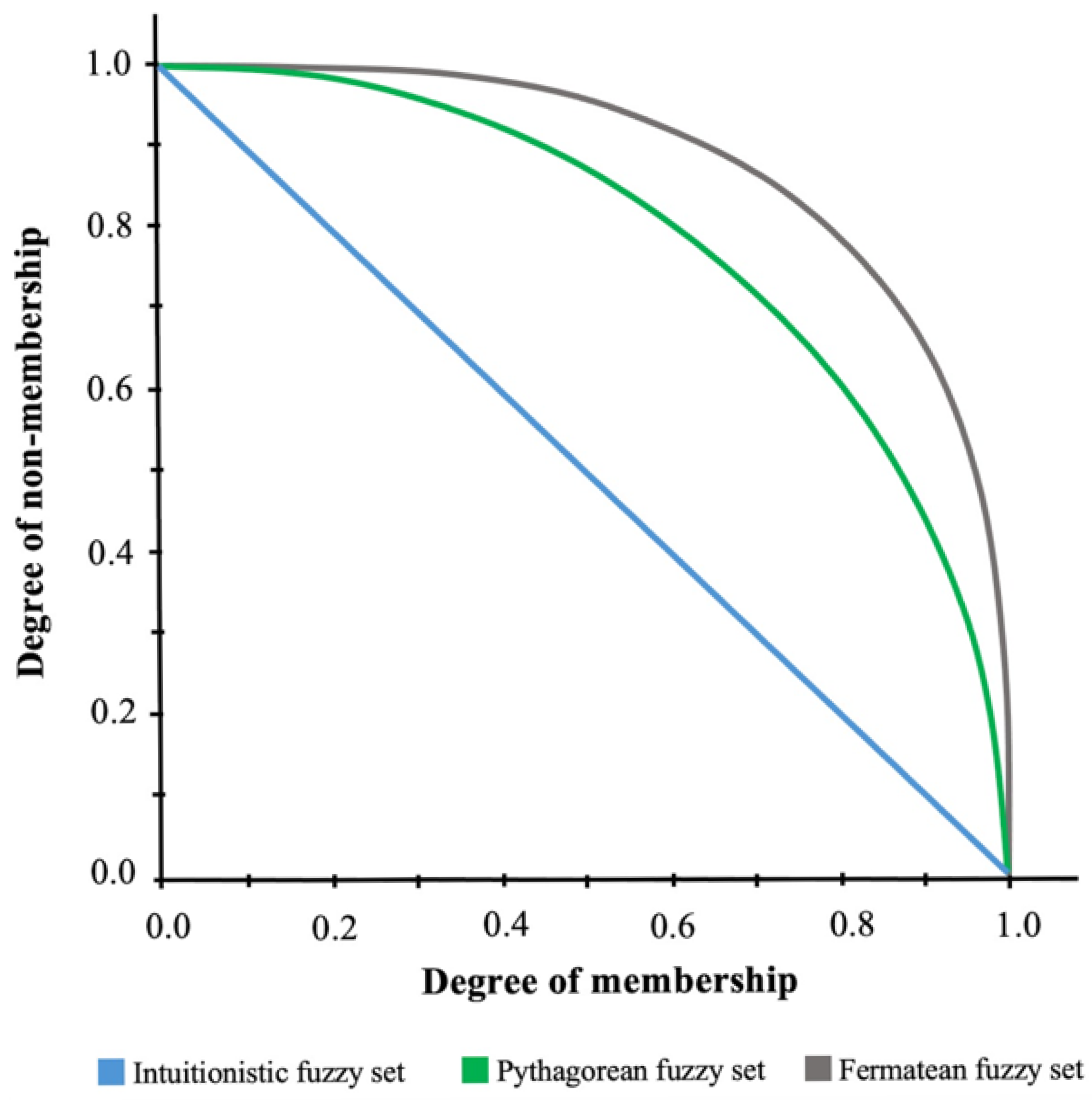

1.1. Motivation for Using Fermatean Fuzzy Sets

1.2. Motivation for SWARA Method Application

1.3. Motivation for VIKOR Method Application

1.4. Motivation for Game-Theoretic Layer Application

1.5. Contribution of the Study

- This study underscores the pressing necessity for Nigeria to give a higher priority to enhancing its SCs for vital medications and vaccines. Ineffective MVSCs are hampering healthcare coverage and access. New business strategies and alternatives are required to address MVSC challenges in Nigeria. Implementing appropriate strategies is critical to overcoming issues and expanding access.

- The study utilizes fuzzy logic techniques to manage uncertainties in decision-making. Criteria to evaluate strategies were defined via previous studies and viewpoints of experts.

- A novel integrated FF-SWARA-VIKOR framework was applied to assess MVSC strategies specifically for the Nigerian context, further extended with a policy-oriented game-theoretic layer.

- Key findings provide new insights, identify knowledge gaps, and offer evidence to inform policymakers on MVSC challenges.

- The remainder of this paper is organized to guide the reader through our research process systematically. Section 2 provides an in-depth review of the literature, establishing the theoretical framework and highlighting key developments in the field. In Section 3, we clearly define the research problem and articulate the central challenges addressed by our study. Building on this foundation, Section 4 details the proposed game-theoretic methodology, while Section 5 demonstrates its practical application. Section 6 then presents a comprehensive sensitivity analysis to evaluate the robustness of our approach. In Section 6, we critically discuss the findings and presents managerial insights, and the paper concludes in Section 7 with research recommendations and suggestions for future work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Decision-Making Approaches Related to MVSCs

2.2. Applications of MCDM Models to MVSCs

| Authors | Empirical Focus | Env. | Method(s) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [65] | Barrier and enabler assessment for the next VSC generation | Fuzzy | AHP, MOORA | India |

| [81] | VSC problem prioritization | Fuzzy | ISM, ANP | India |

| [66] | VSC risk assessment | Crisp | DEMATEL, ANP | Indonesia |

| [67] | Solving the issue related to sustainable vaccine distribution | Crisp | BWM, MARCOS | India |

| [68] | Strategy analysis to address the environmental effect of VSC | Fuzzy | DEMATEL | India |

| [69] | Sustainable VSC modeling | Crisp | MOSEO, MOFEPSO, TOPSIS | Bangladesh |

| [70] | Optimization of the VSC challenges | Crisp | DEMATEL | - |

| [71] | Establishment of strategies for a durable and flexible VSC | Fuzzy | DEMATEL | Bangladesh |

| This study | Prioritizing the policies for sustainable MVSCs | Fuzzy | SWARA, VIKOR, Game Theory | Nigeria |

2.3. Research Gaps

3. Problem Definition

3.1. Alternatives Definition

3.2. Criteria Definition

4. Proposed Game-Theoretic Methodology

| Algorithm 1. Three-Stage FF–SWARA–VIKOR–Game Theoretic Framework |

| Stage 1. FF-SWARA Input: Expert set , Criteria set , Fermatean fuzzy linguistic scale//see Table 4 Output: Final normalized FF–SWARA weights for all criteria. Begin ← Establish the aggregated decision matrix: ← Obtain expert evaluations for each criterion using FF LTs//see Table 4. Translate each into an FFN//see Table 4. ← Aggregate expert opinions for each criterion using the FFWG operator//see Equation (10). ← Compute the positive score for each criterion//see Equation (11). Rank criteria in descending order based on the positive score values. ← Excluding the first-ranked criterion, compute the comparative significance of each remaining criterion by comparing its value with that of the previous criterion in the ordered list. ← Set the comparative coefficient of the first-ranked criterion to 1; compute it for each of the remaining criteria accordingly//see Equation (12). ← Set the recalculated weight of the first-ranked criterion to 1; iteratively determine it for the remaining criteria//see Equation (13). ← Normalize all recalculated weights using sum-based normalization to obtain the final weights//see Equation (14). End Stage 2. FF-VIKOR Input: Final weights (from Stage 1), Alternatives , Strategy weight τ for balancing group utility and individual regret; typically set to 0.5 Output: Compromise ranking of alternatives and the best alternative(s) Begin ← Obtain expert evaluations of each alternative under every criterion using the FF linguistic terms//see Table S1. ← Aggregate expert evaluations into the aggregated FF decision matrix using the FFWG operator//see Equation (9). Determine ideal solutions: ← Determine the positive ideal solution containing the best performance values for each criterion//see Equation (15). ← Determine the negative ideal solution containing the worst performance values for each criterion//see Equation (16). , ← Compute the group utility and individual regret measures for each alternative using the weighted Euclidean distance calculation//see Equations (17) and (18). ← Calculate the compromise index integrating and through the strategy weight //see Equation (19). Rank alternatives in ascending order of their values: If two alternatives have equal , use and as tie-breakers. Identify the alternative with the lowest as the candidate compromise solution (Alt′) and the second-lowest as (Alt″). Verify the two VIKOR acceptability conditions for (Alt′). Acceptable advantage: , where //see Condition-1. Acceptable stability in decision-making: (Alt′) must also rank first in either or ordering//see Condition-2. Determine compromise solution: If both Condition-1 and Condition-2 are satisfied, (Alt′) is the unique compromise solution. If only Condition-2 fails, include (Alt′) and (Alt″) in the compromise set. If only Condition-1 fails, extend the set to include all alternatives up to such that . End Stage 3. Game-Theoretic Layer Input: Strategic weighting scenarios set representing different governmental orientations, Alternatives Output: Equilibrium policy (pure or mixed) and the guaranteed VIKOR level Begin |

| ← For each , run the FF-VIKOR procedure to evaluate the performance of each policy . ← Convert values into a payoff matrix to fit the zero-sum game formulation//see Equation (20). , ← Compute security level for scenarios (strategy selector) and upper value for policy alternatives (policy maker)//see Equations (21) and (22). , Determine minimum of values and maximum of values. Examine whether a saddle point exists: A saddle point (i.e., pure-strategy Nash equilibrium) exists at where . If no saddle point exists (maximin ≠ minimax), formulate the mixed-strategy linear programming model for the policy player (row)//see Equation (23). , ← Solve the model for the optimal value of the game ( and probability vector (optimal mixed policy ). ← Compute the guaranteed VIKOR level//see Equation (24). , ← Formulate and solve the dual LP for the strategy selector (column)//see Equation (25). |

| End of Algorithm |

4.1. Stage-1: SWARA Method Equipped with FFNs (FF-SWARA)

4.2. Stage-2: VIKOR Method Equipped with FFNs (FF-VIKOR)

4.3. Stage-3: Game-Theoretic Layer

5. Application of the Proposed Methodology

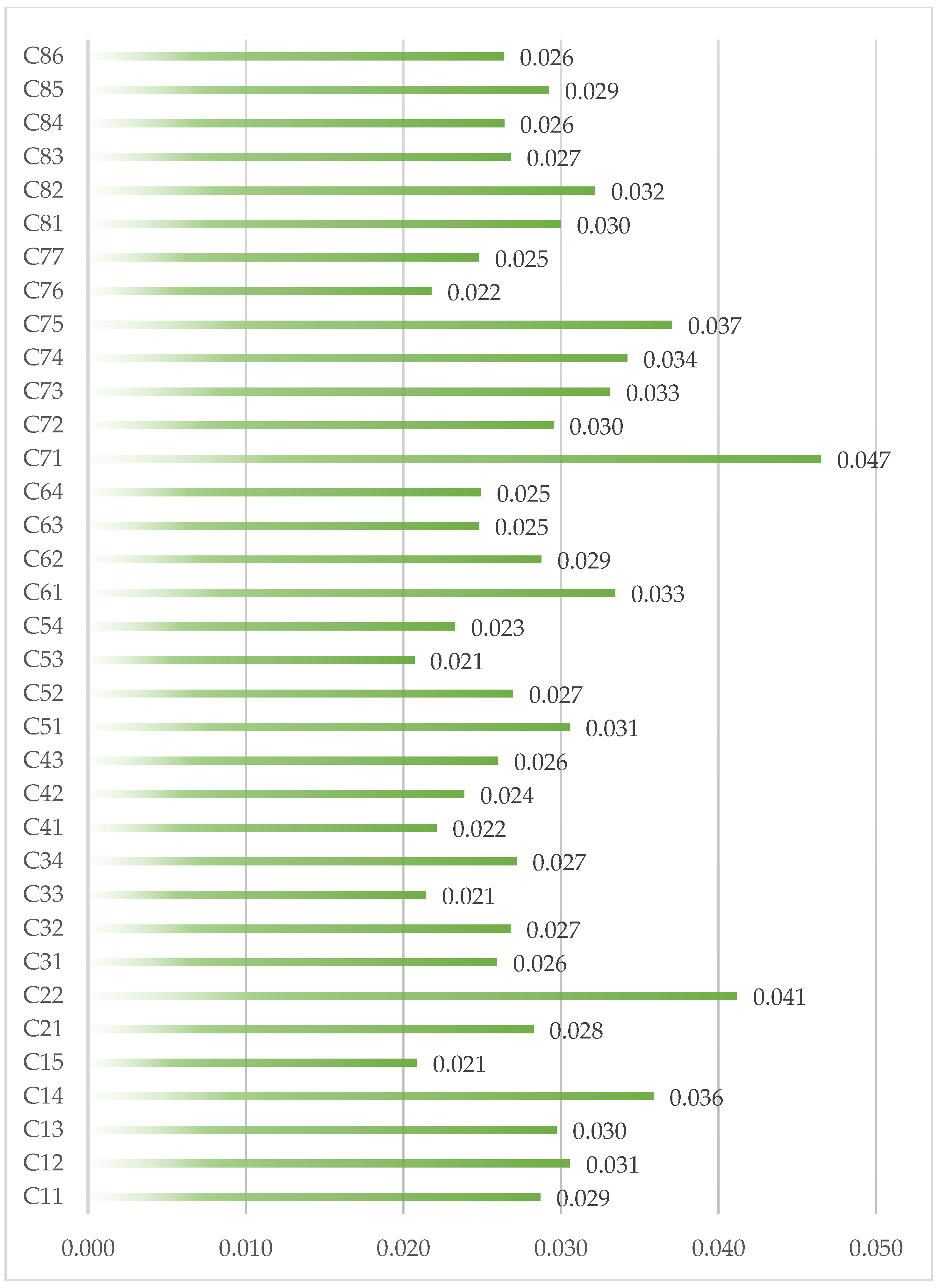

5.1. Criteria Weights Determination

5.2. Evaluating the Alternatives

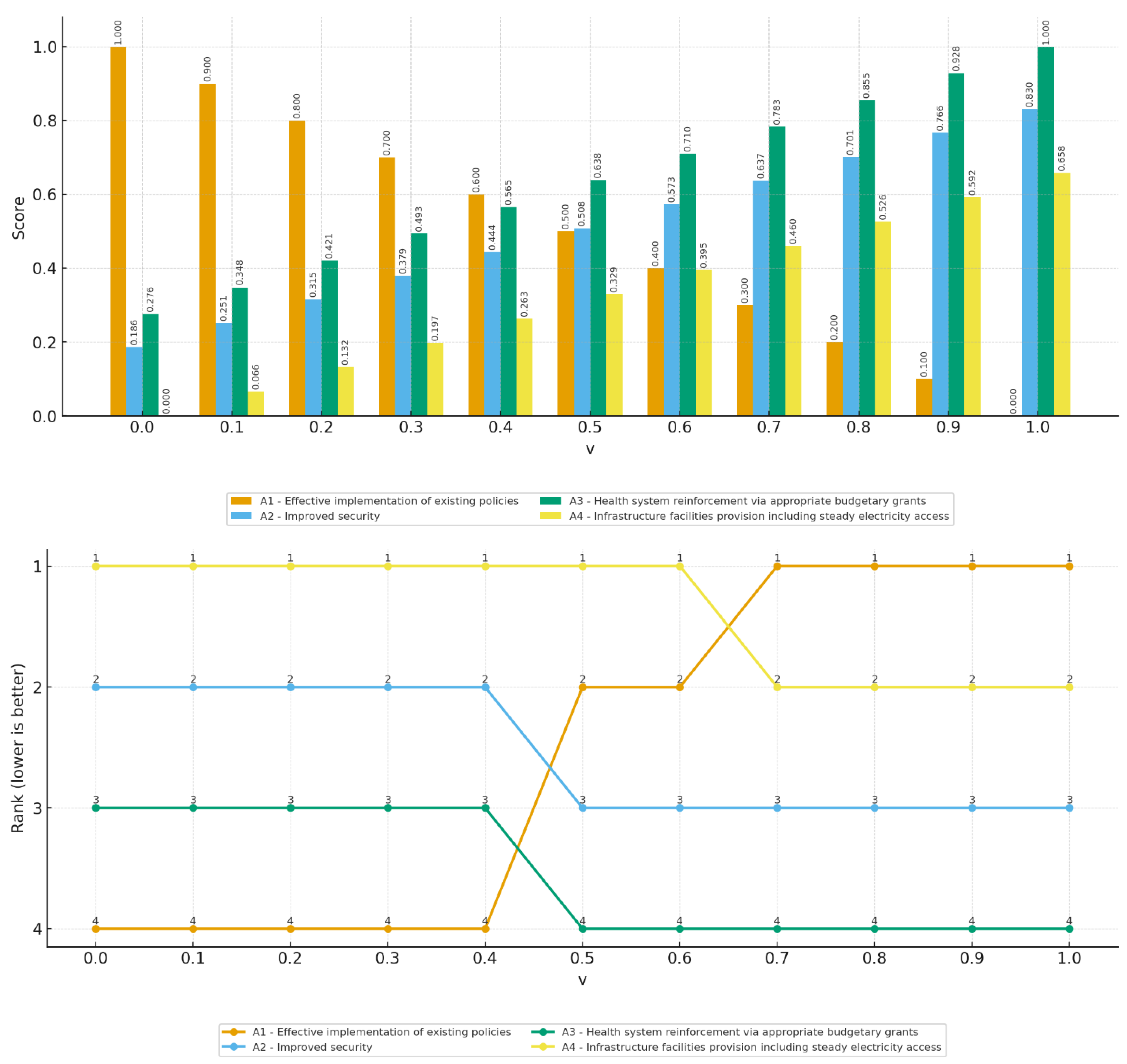

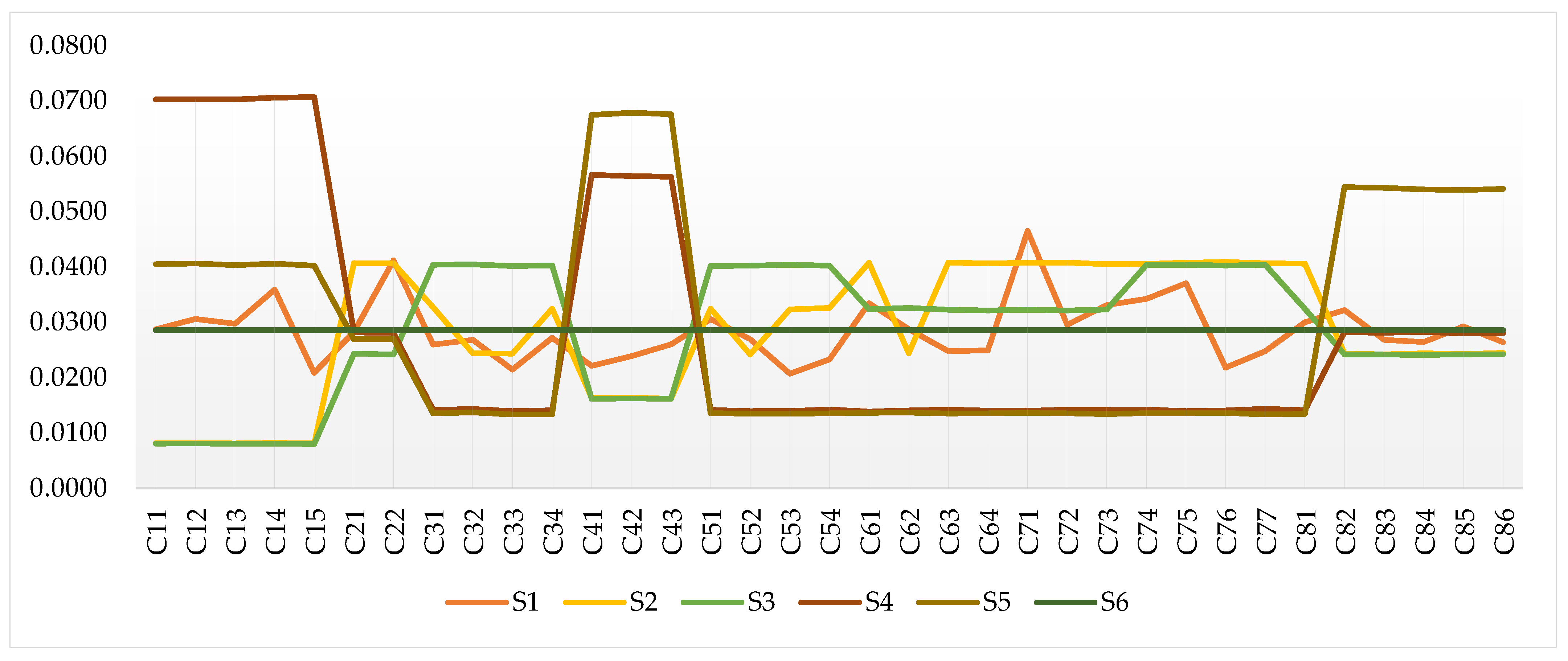

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5.4. Comparative Analysis

5.5. Investigating Policy Robustness Through Game Theory

6. Findings and Discussion

Managerial Insights

- ○

- Policy reforms and system strengthening

- •

- Remove barriers in pharmaceutical importation.

- •

- Develop alternative strategies to ensure a steady supply of essential drugs.

- •

- Diversify funding sources and improve donor coordination.

- ○

- Cold chain and quality assurance

- •

- Emphasize careful handling throughout the cold chain.

- •

- Implement stricter monitoring of power outages, generator usage, and fuel consumption.

- •

- Adopt robust packaging strategies to minimize product and package damage.

- ○

- Human resources and capacity building

- •

- Invest in education and training programs to nurture a skilled pharmaceutical supply chain workforce.

- •

- Develop specialized courses, certifications, and on-the-job training for logistics and SC professionals.

- •

- Provide competitive compensation and career development opportunities to attract and retain talent.

- ○

- Strategic robustness from game-theoretic analysis

- •

- No pure saddle-point solution exists; instead, a mixed strategy emerges as the most robust option.

- •

- A1 (Effective Implementation of Existing Policies) is the backbone of a resilient policy.

- •

- A4 (Strengthening Distribution and Storage Systems) complements A1 to hedge against shifts between and .

- •

- If is more likely, emphasis should tilt toward A1; if dominates, the share of A4 gains strategic importance.

7. Conclusions and Further Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FF-SWARA | Fermatean Fuzzy Stepwise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis |

| FF-VIKOR | Fermatean Fuzzy VIšeKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje |

| SC | supply chain |

| MVSC | medicine and vaccine supply chains |

| MCDM | multi-criteria decision-making |

| FF | Fermatean fuzzy |

| FFS | Fermatean fuzzy set |

| FFN | Fermatean fuzzy number |

| VSC | vaccine supply chain |

| LT | linguistic terms |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development|Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Aigbavboa, S.; Mbohwa, C. The Headache of Medicines’ Supply in Nigeria: An Exploratory Study on the Most Critical Challenges of Pharmaceutical Outbound Value Chains. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 43, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, C.; Tsui, E.K. How the Quality of Essential Medicines Is Perceived and Maintained through the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: A Perspective from Stakeholders in Nigeria. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 1344–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, O.A.; Chukwu, U.; Lemoha, C. Poor Performance of Medicines Logistics and Supply Chain Systems in a Developing Country Context: Lessons from Nigeria. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 9, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiny, O. Counterfeit Drugs in Nigeria: A Threat to Public Health. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 2571–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatokun, O. Curbing the Circulation of Counterfeit Medicines in Nigeria. Lancet 2016, 388, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ogbonna, B.O.; Ilika, A.L.; Nwabueze, S.A. National Drug Policy in Nigeria, 1985–2015. World J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 4, 248–264. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R.E.; Zadeh, L.A. Decision-Making in a Fuzzy Environment. Manag. Sci. 1970, 17, B-141–B-164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelissari, R.; Oliveira, M.C.; Abackerli, A.J.; Ben-Amor, S.; Assumpção, M.R.P. Techniques to Model Uncertain Input Data of Multi-criteria Decision-making Problems: A Literature Review. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 523–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisud, D.; Kongkaew, W. A Hybrid CORELAP-Association Rules and Fuzzy AHP Framework for Plant Layout Optimization in the Para Rubber Plywood Industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 295, 128766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztaysi, B.; Onar, S.C.; Cebi, S.; Kahraman, C. Fuzzy MCDM Approaches in Sustainability Research: A Literature Review. In Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems; Kahraman, C., Cebi, S., Oztaysi, B., Cevik Onar, S., Tolga, C., Ucal Sari, I., Otay, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1528, pp. 830–838. ISBN 978-3-031-97984-2. [Google Scholar]

- Karnik, N.N.; Mendel, J.M. Operations on Type-2 Fuzzy Sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2001, 122, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. A Note on Z-Numbers. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 2923–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramot, D.; Milo, R.; Friedman, M.; Kandel, A. Complex Fuzzy Sets. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2002, 10, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, K.T. Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. Pythagorean Fuzzy Subsets. In Proceedings of the 2013 Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–28 June 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Fermatean Fuzzy Weighted Averaging/Geometric Operators and Its Application in Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 85, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, H.; Shahzadi, G.; Akram, M. Decision-Making Analysis Based on Fermatean Fuzzy Yager Aggregation Operators with Application in COVID-19 Testing Facility. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 7279027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, V.; Ivanović, I.; Đorić, V.; Torkayesh, A.E. Adapting Urban Transport Planning to the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Fermatean Fuzzy Model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Shahzadi, G.; Ahmadini, A.A.H. Decision-Making Framework for an Effective Sanitizer to Reduce COVID-19 under Fermatean Fuzzy Environment. J. Math. 2020, 2020, 3263407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, M.S.; Siddique, I.; Ahsan, M.; Jarad, F.; Altunok, T. An Approach of Decision-Making under the Framework of Fermatean Fuzzy Sets. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8442123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Ayyildiz, E.; Ozcelik, G.; Tengecha, N.A.; Stević, Ž. Alternative Prioritization for Mitigating Urban Transportation Challenges Using a Fermatean Fuzzy-Based Intelligent Decision Support Model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 7343–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keršulienė, V.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z. Selection of Rational Dispute Resolution Method By Applying New Step-Wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA). J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2010, 11, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E. Fermatean Fuzzy Step-Wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) and Its Application to Prioritizing Indicators to Achieve Sustainable Development Goal-7. Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Qiu, Y.; Stević, Ž.; Marinković, D.; Deveci, M. Integrated Intelligent Decision Support Model for Ranking Regional Transport Infrastructure Programmes Based on Performance Assessment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 222, 119852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Qiu, Y.; Ayyildiz, E.; Yildiz, A. Prioritization of Strategies for a Sustainable Regional Transportation Infrastructure by Hybrid Spherical Fuzzy Group Decision-Making Approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 17967–17986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E.; Yildiz, A.; Taskin Gumus, A.; Ozkan, C. An Integrated Methodology Using Extended Swara and Dea for the Performance Analysis of Wastewater Treatment Plants: Turkey Case. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Qiu, Y.; Yusupov, B.; Ndjegwes, C.M. A Study on the Development Strategy of the Railway Transportation System in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) Based on the SWOT/AHP Technique. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Qiu, Y.; Stević, Ž.; Simić, V. Assessment of Alternative Railway Systems for Sustainable Transportation Using an Integrated IRN SWARA and IRN CoCoSo Model. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 86, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E. A Novel Pythagorean Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methodology for e-Scooter Charging Station Location-Selection. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 111, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, I.; Pamucar, D.; Gigović, L.; Tatomirović, S. Optimal Site Selection for Sitting a Solar Park Using a Novel GIS-SWA’TEL Model: A Case Study in Libya. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanackov, I.; Badi, I.; Stević, Ž.; Pamučar, D.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Bausys, R. A Novel Hybrid Interval Rough SWARA–Interval Rough ARAS Model for Evaluation Strategies of Cleaner Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraima, M.B.; Tengecha, N.A.; Stević, Ž.; Simić, V.; Qiu, Y. An Integrated Fuzzy MCDM Model for Prioritizing Strategies for Successful Implementation and Operation of the Bus Rapid Transit System. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 342, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamucar, D.; Yazdani, M.; Montero-Simo, M.J.; Araque-Padilla, R.A.; Mohammed, A. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis towards Robust Service Quality Measurement. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 170, 114508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Ali, M.I.; Kumam, P.; Kumam, W.; Aslam, M.; Alcantud, J.C.R. Improved Generalized Dissimilarity Measure-based VIKOR Method for Pythagorean Fuzzy Sets. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 1807–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, M.; Gokasar, I.; Pamucar, D.; Zaidan, A.A.; Wen, X.; Gupta, B.B. Evaluation of Cooperative Intelligent Transportation System Scenarios for Resilience in Transportation Using Type-2 Neutrosophic Fuzzy VIKOR. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 172, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, M.; Meena, A.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Selection and Ranking of Dental Restorative Composite Materials Using Hybrid Entropy-VIKOR Method: An Application of MCDM Technique. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 147, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, W.; Fan, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. A Novel Hybrid MCDM Model for Machine Tool Selection Using Fuzzy DEMATEL, Entropy Weighting and Later Defuzzification VIKOR. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 91, 106207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, T.; Ye, M.; Lin, H.; Li, Z. A Hybrid Fuzzy BWM-VIKOR MCDM to Evaluate the Service Level of Bike-Sharing Companies: A Case Study from Chengdu, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimian, S.; Mousavi, S.; Antucheviciene, J. An Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Model Based on Extended VIKOR and MARCOS for Sustainable Supplier Selection in Organ Transplantation Networks for Healthcare Devices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Torkayesh, A.E.; Tavana, M.; Goli, A.; Simic, V.; Ding, W. An Integrated Decision Support Framework for Resilient Vaccine Supply Chain Network Design. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Goli, A.; Ghasemi, P.; Goodarzian, F. Designing a Sustainable Closed-Loop Supply Chain Network of Face Masks during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Pareto-Based Algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzian, F.; Taleizadeh, A.A.; Ghasemi, P.; Abraham, A. An Integrated Sustainable Medical Supply Chain Network during COVID-19. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 100, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Jørgensen, T.B.; Nielsen, T.S. Supply Chain 4.0 Performance Measurement: A Systematic Literature Review, Framework Development, and Empirical Evidence. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Aydin, N.S. Integrated Design of Sustainable Supply Chain and Transportation Network Using a Fuzzy Bi-Level Decision Support System for Perishable Products. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 195, 116628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Lev, B. Cold Chain Transportation Decision in the Vaccine Supply Chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Zahmatkesh, S.; Bokhari, A.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. Designing a Vaccine Supply Chain Network Considering Environmental Aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, J.; Boloukifar, S.; Soltani, S.; Jabalbarezi Hookerd, E.; Fouladi, F.; Andreevna Rushchtc, A.; Du, B.; Shen, J. Designing an Optimization Model for the Vaccine Supply Chain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 214, 119009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazvar, Z.; Tafakkori, K.; Oladzad, N.; Nayeri, S. A Capacity Planning Approach for Sustainable-Resilient Supply Chain Network Design under Uncertainty: A Case Study of Vaccine Supply Chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 159, 107406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Lim, M.K. Vaccine Supply Chain Management: An Intelligent System Utilizing Blockchain, IoT and Machine Learning. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.A.; Kia, R.; Goodarzian, F.; Ghasemi, P. A New Vaccine Supply Chain Network under COVID-19 Conditions Considering System Dynamic: Artificial Intelligence Algorithms. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 85, 101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Lev, B. Influenza Vaccine Supply Chain Coordination under Uncertain Supply and Demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 930–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.T.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, S.M.; Sarker, S.; Kabir, G.; Ul-Islam, A. Challenges to COVID-19 Vaccine Supply Chain: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 239, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, O.T.; Olusegun, A.; Paul, O.A.; Felix, S.O.; Kaniki, F.R.; Ayosanmi, O.S.; Wade, D.; Faith, A.O.; Terna, G.Z.; Musa, A.; et al. The Use of UAV/Drones in the Optimization of Nigeria Vaccine Supply Chain. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2019, 10, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Omole, T.M.; Sanni, F.O.; Olaiya, P.A.; Ajani, O.F.; Aiden, P.J.; Njemanze, C.G. The Challenges of Nigeria Vaccine Supply Chain, a Community of Practice Perspective. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2019, 6, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Abiodun, O.P.; Sanni, F.; Aiden, J.; Musa, A.; Njemanze, C.; Ayosanmi, O.; Olusegun, A.; Ajani, F.; Kaniki, F.; Wade, D. Thermostable Vaccines in the Optimization of African Vaccine Supply Chain the Perspective of the Nigerian Health Supply Chain Professionals. Glob. Sci. J. 2020, 7, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Olutuase, V.O.; Iwu-Jaja, C.J.; Akuoko, C.P.; Adewuyi, E.O.; Khanal, V. Medicines and Vaccines Supply Chains Challenges in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, O.A.; Adibe, M. Quality Assessment of Cold Chain Storage Facilities for Regulatory and Quality Management Compliance in a Developing Country Context. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Kumar, D. Two-Way Assessment of Key Performance Indicators to Vaccine Supply Chain System in India. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 194–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliyogbinda, J.; Tijjani, U. Framework for Integration of Vertical Public Health Supply Chain Systems: A Case Study of Nigeria. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Wijethilaka, H.P.G.D. Post-COVID-19 Vaccine Supply Chain: Challenges, Disruptions, and Digital Transformation. In Revolutionizing Supply Chains Through Digital Transformation; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 251–280. ISBN 979-8-3693-4427-9. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna Varigonda, V.; Borole, A.; Hudge, A.; Yadav, C.; Kumar Annamalai, V. Feasibility of Multi-Configuration Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Last Mile Delivery of Medical Supplies. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Pune, India, 27–29 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, I.; Mota, B.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P. Pharmaceutical Industry Supply Chains: Planning Vaccines’ Distribution. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 51, pp. 1009–1014. ISBN 978-0-323-95879-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, D.; Vipin, B.; Kumar, D. A Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Framework to Identify Barriers and Enablers of the next-Generation Vaccine Supply Chain. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 72, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarmin, A.C.; Ardi, R. DEMATEL-Based Analytic Network Process (ANP) Approach to Assess the Vaccine Supply Chain Risk in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 14–17 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 726–730. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, D. A LAG-Based Framework to Overcome the Challenges of the Sustainable Vaccine Supply Chain: An Integrated BWM–MARCOS Approach. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 13, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Kumar, D. Analysis of Strategies to Tackle the Environmental Impact of the Vaccine Supply Chain: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. In Advances in Modelling and Optimization of Manufacturing and Industrial Systems; Singh, R.P., Tyagi, M., Walia, R.S., Davim, J.P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 533–547. ISBN 978-981-19-6106-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, N.R.; Ahmed, M.; Mahmud, P.; Paul, S.K.; Liza, S.A. Modeling a Sustainable Vaccine Supply Chain for a Healthcare System. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, M.; Srivastav, P.; Dhiman, A.; Shuaib, M. A Statistical Study for Optimizing the Challenges in Vaccine Supply Chain During Critical Times Using DEMATEL Method. In Advances in Mechanical Engineering and Technology; Singari, R.M., Kankar, P.K., Moona, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 429–438. ISBN 978-981-16-9612-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, P.; Ahmed, M.; Janan, F.; Xames, M.D.; Chowdhury, N.R. Strategies to Develop a Sustainable and Resilient Vaccine Supply Chain in the Context of a Developing Economy. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 87, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, M.; Tavana, M.; Meraj, A.; Mina, H. An Inventory-Location Optimization Model for Equitable Influenza Vaccine Distribution in Developing Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccine 2021, 39, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, M.S.; Trump, B.D.; Cegan, J.C.; Linkov, I. Supply Chain Resilience for Vaccines: Review of Modeling Approaches in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 1723–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Sezer, M.D.; Ozbiltekin-Pala, M.; Kucukvar, M. Investigating the Role of Stakeholder Engagement for More Resilient Vaccine Supply Chains during COVID-19. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, E.; Üner, S.İ.; Demir, A.; Dinler, S.; Alakaş, H.M. Prioritizing Individuals Who Will Have Covid-19 Vaccine with Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2023, 36, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M.; Ayyildiz, E. Investigation of the Pharmaceutical Warehouse Locations under COVID-19—A Case Study for Duzce, Turkey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 116, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S.A.; Warsi, S.S. Exploring the Synergy between Sustainability and Resilience in Supply Chains under Stochastic Demand Conditions and Network Disruptions. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.M.; Shukla, O.J.; Kumar, A. An Integrated Fuzzy Dematel-BWM Method to Analyse Critical Factors for Sustainable Vaccine Supply Chain in Low-Middle Income Nations. Int. J. Multicriteria Decis. Mak. 2024, 10, 10068245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, S.; Jain, A.; Ramamoorthy, P.; Ramamohan, V. A Decision Support Framework for Optimal Vaccine Distribution across a Multi-Tier Cold Chain Network. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrak, F.; Cantürk, S. Strategic Multi-Criteria Assessment for Cold Chain Logistics Optimization in the Aviation Sector. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.; Kumar, D. Prioritizing the Vaccine Supply Chain Issues of Developing Countries Using an Integrated ISM-Fuzzy ANP Framework. J. Model. Manag. 2019, 15, 112–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarley, D.; Mahmud, M.; Idris, J.; Osunkiyesi, M.; Dibosa-Osadolor, O.; Okebukola, P.; Wiwa, O. Transforming Vaccines Supply Chains in Nigeria. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2167–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Paul, S.K.; Kaisar, S.; Moktadir, M.A. COVID-19 Pandemic Related Supply Chain Studies: A Systematic Review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 148, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qrunfleh, S.; Vivek, S.; Merz, R.; Mathivathanan, D. Mitigation Themes in Supply Chain Research during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2023, 30, 1832–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, I.R.; Colapinto, C. Multiple Criteria Decision-making in Healthcare and Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Management: A State-of-the-art Review and Implications for Future Research. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2022, 29, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, O.U.; Ali, Y. Enhancing Healthcare Supply Chain Resilience: Decision-Making in a Fuzzy Environment. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 520–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atcha, P.; Vlachos, I.; Kumar, S. Inventory Sharing in Healthcare Supply Chains: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 1107–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Čereška, A.; Matijošius, J.; Rimkus, A.; Bausys, R. Internal Combustion Engine Analysis of Energy Ecological Parameters by Neutrosophic MULTIMOORA and SWARA Methods. Energies 2019, 12, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ren, J.; Wang, J.; Paraskevadakis, D.; Morecroft, C. A Comprehensive Analysis of Diverse Risk Management Strategies in Healthcare Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Xi’an, China, 4–6 August 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1247–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Barrios, M.; Gul, M.; Yucesan, M.; Alfaro-Sarmiento, I.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Jiménez-Delgado, G. A Fuzzy Hybrid Decision-Making Framework for Increasing the Hospital Disaster Preparedness: The Colombian Case. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 72, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, V.; Mangla, S.K.; Tiwari, B. Managing Healthcare Waste for Sustainable Environmental Development: A Hybrid Decision Approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Mani, V.; Kamble, S.S.; Khan, S.A.R.; Verma, S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Innovation for Enhancing Supply Chain Resilience and Performance under the Effect of Supply Chain Dynamism: An Empirical Investigation. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 333, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritchanchai, D.; Senarak, D.; Supeekit, T.; Chanpuypetch, W. Evaluating Supply Chain Network Models for Third Party Logistics Operated Supply-Processing-Distribution in Thai Hospitals: An AHP-Fuzzy TOPSIS Approach. Logistics 2024, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settanni, E.; Harrington, T.S.; Srai, J.S. Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Models: A Synthesis from a Systems View of Operations Research. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2017, 4, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchenine, A.; Almaraj, I. A Multi-Objective Robust Optimization Model with Defective Vaccine and Reverse Supply Chain under Uncertainty. J. Model. Manag. 2025, 20, 1537–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu-Jaja, C.J.; Jordan, P.; Ngcobo, N.; Jaca, A.; Iwu, C.D.; Mulenga, M.; Wiysonge, C. Improving the Availability of Vaccines in Primary Healthcare Facilities in South Africa: Is the Time Right for a System Redesign Process? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1926184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, M.; Gruchmann, T.; Oelze, N. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Conceptual Framework and Future Research Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Bari, A.B.M.M.; Haq, M.M.; De Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; Khan, M.A. An Integrated Stepwise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis and Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment Framework for Sustainable Supplier Selection in the Healthcare Supply Chains. Supply Chain Anal. 2023, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Debnath, B.K.; Chatterjee, P.; Panaiyappan, A.K.; Das, S.; Anusha, G. Generalized Dombi-Based Probabilistic Hesitant Fuzzy Consensus Reaching Model for Supplier Selection under Healthcare Supply Chain Framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavian, S.B.; Tirkolaee, E.B.; Simic, V.; Ali, S.S.; Görçün, Ö.F. Blockchain-Enabled Healthcare Supply Chain Management: Identification and Analysis of Barriers and Solutions Based on Improved Zero-Sum Hesitant Fuzzy Game Theory. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumrit, D. Unveiling the Effects of Big Data Analytic Capability on Improving Healthcare Supply Chain Resilience: An Integrated MCDM with Spherical Fuzzy Information Approach. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande-Sholabi, W.; Adebisi, Y.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Medicine Security in Africa: Nigeria as a Case Study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Lin, X. Current Efforts and Challenges Facing Responses to 2019-nCoV in Africa. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwujekwe, O.; Ezumah, N.; Mbachu, C.; Obi, F.; Ichoku, H.; Uzochukwu, B.; Wang, H. Exploring Effectiveness of Different Health Financing Mechanisms in Nigeria; What Needs to Change and How Can It Happen? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaza, R.K.; O’Connell, T.S.; Chapčáková, I. Players and Processes behind the National Health Insurance Scheme: A Case Study of Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzochukwu, B.; Ughasoro, M.; Etiaba, E.; Okwuosa, C.; Envuladu, E.; Onwujekwe, O. Health Care Financing in Nigeria: Implications for Achieving Universal Health Coverage. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 18, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, O.A.; Ezeanochikwa, V.N.; Eya, B.E. Supply Chain Management of Health Commodities for Reducing Global Disease Burden. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboreime, E.; Abimbola, S.; Bozzani, F. Access to Routine Immunization: A Comparative Analysis of Supply-Side Disparities between Northern and Southern Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palafox, B.; Patouillard, E.; Tougher, S.; Goodman, C.; Hanson, K.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Rueda, S.T.; Kiefer, S.; O’Connell, K.A.; Zinsou, C.; et al. Understanding Private Sector Antimalarial Distribution Chains: A Cross-Sectional Mixed Methods Study in Six Malaria-Endemic Countries. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatau, B.; Avong, Y.; Ogundahunsi, O.; Shah, S.; Tayler Smith, K.; Van Den Bergh, R.; Zachariah, R.; Van Griensven, J.; Ekong, E.; Dakum, P. Procurement and Supply Management System for MDR-TB in Nigeria: Are the Early Warning Targets for Drug Stock Outs and over Stock of Drugs Being Achieved? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surakat, O.A.; Sam-Wobo, S.O.; Ademolu, K.O.; Adekunle, M.F.; Adekunle, O.N.; Monsuru, A.A.; Awoyale, A.K.; Oyinloye, N.; Omitola, O.O.; Bankole, S.O.; et al. Assessment of Community Knowledge and Participation in Onchocerciasis Programme, Challenges in Ivermectin Drug Delivery, Distribution and Non-Compliance in Ogun State, Southwest Nigeria. Infect. Dis. Health 2018, 23, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, E.; Harnly, M.; Whitaker, S.; Miller, R. Reorganizing Nigeria’s Vaccine Supply Chain Reduces Need for Additional Storage Facilities, but More Storage Is Required. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Magaji, M.; Lawal, G.; Masoud, M. Medicine Supply Management in Nigeria: A Case Study of Ministry of Health, Kaduna State. Niger. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 6, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Obioha, E.E.; Ajala, A.S.; Matobo, T.A. Analysis of the Performance of Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) for Four Child Killer Diseases under the Military and Civilian Regimes in Nigeria, 1995–1999; 2000–2005. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2010, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeka, I.; Ilika, A.; Ilika, F.; Umeh, D.; Onyibe, R.; Okoye, C.; Diden, G.; Onubogu, C. Experiences from Polio Supplementary Immunization Activities in Anambra State, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 17, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dairo, D.M.; Osizimete, O.E. Factors Affecting Vaccine Handling and Storage Practices among Immunization Service Providers in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2016, 16, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, A.S.; Willis, F.; Nwaze, E.; Dieng, B.; Sipilanyambe, N.; Daniels, D.; Abanida, E.; Gasasira, A.; Mahmud, M.; Ryman, T.K. Vaccine Wastage in Nigeria: An Assessment of Wastage Rates and Related Vaccinator Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6751–6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, D.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Shao, X. Enhanced State-Constrained Adaptive Fuzzy Exact Tracking Control for Nonlinear Strict-Feedback Systems. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2026, 522, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, V.; Gokasar, I.; Deveci, M.; Isik, M. Fermatean Fuzzy Group Decision-Making Based CODAS Approach for Taxation of Public Transit Investments. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 4233–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.; Lo, H.-W.; Yucesan, M. Fermatean Fuzzy TOPSIS-Based Approach for Occupational Risk Assessment in Manufacturing. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 2635–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, H.; Ozkir, V. A Fermatean Fuzzy MCDM Method for Selection and Ranking Problems: Case Studies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiva, E.; Hashim, H.T.; Ramadhan, M.A.; Musa, S.K.; Bchara, J.; Tuama, Y.D.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Kadhim, M.H.; Essar, M.Y.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Drug Supply Shortage in Nigeria during COVID-19: Efforts and Challenges. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2021, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, T. Challenges in the Logistics Management of Vaccine Cold Chain System in Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. J. Community Med. Prim. Health Care 2019, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, G.; Sarkar, P.; Singla, E.; Singh, H.; Sharma, R.K. Comparison of Environmental Sustainability of Pharmaceutical Packaging. Perspect. Sci. 2016, 8, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (s) | Empirical Focus | GDM | SA | Method(s) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | Discussion of the distributor’s transport decision for cold chain vaccine adoption | No | No | Cold chain transportation decision model | China |

| [48] | VSC activities analysis on economy and environment | No | No | Multi-objective mixed-integer programming model | Iran |

| [49] | Optimization model design of VSC | No | No | Bi-level optimization model | Iran |

| [50] | SC network design | No | No | Fuzzy optimization approach | Iran |

| [51] | Intelligent VSC management establishment | No | No | Machine learning, sentiment analysis | - |

| [52] | Design of a system dynamic frame for COVID-19 emergence | No | No | Stochastic simulation-optimization model | - |

| [53] | Coordination of Influenza VSC | No | No | Two-ordering strategy model | - |

| [54] | Assessment of challenges to COVID-19 VSC | Yes | No | IF-DEMATEL | Developing countries |

| [56] | Exploration of the VSC ecosystem | Yes | No | Questionnaire | Nigeria |

| [55] | Optimization of VSC via drones’ usage | Yes | No | Questionnaire | Nigeria |

| Optimization of VSC through health professionals’ perspective | Yes | No | Questionnaire | Nigeria | |

| This study | Prioritizing the policies for sustainable MVSCs | Yes | Yes | FF-SWARA-VIKOR, Game Theory | Nigeria |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria |

|---|---|

| Human resource challenges (C1) | Challenges experienced by pharmacists with the various aspects of the supply chain (C11) |

| Lack of support for personnel involved in medicine logistics (C12) | |

| Inadequate personnel (C13) | |

| Lack of human resources as well as corruption (C14) | |

| Killing of personnel due to insurgency (C15) | |

| Financial challenges (C2) | Lack of financial resources (C21) |

| Poor funding for vaccine supply (C22) | |

| Delay, transportation and distributions challenges (C3) | Delays in importation and difficulty in maintaining delivery vehicles (C31) |

| Distribution issues due to delayed or inaccurate inventory reporting (C32) | |

| Insecurity during transportation of vaccines and logistics distance between manufacturer and Nigeria (C33) | |

| Inability to monitor and maintain optimum temperatures for vaccines during transportation (C34) | |

| Policies and standard operating Procedure challenges (C4) | Inadequate implementation of medicine distribution policies (C41) |

| Sub-optimal implementation of policies (C42) | |

| Non-adherence to policies (C43) | |

| Infrastructure and storage challenges (C5) | Disruption of the supply chain through the destruction of storage facilities (C51) |

| Inadequate storage facilities for ivermectin (C52) | |

| Inadequate cold storage facilities (C53) | |

| Inadequate ice-packs (C54) | |

| Issues including medicines or vaccines stockouts (C6) | Stock-outs (C61) |

| Substandard medicines (C62) | |

| Shortages and unreliable vaccine supply (C63) | |

| Regular stock-outs of essential medicines due to inefficient inventory management systems (C64) | |

| Technical issues (C7) | Interruption of drug supplies (C71) |

| Unreliable vaccine supply (C72) | |

| Inefficient procurement systems (C73) | |

| Damaged products and packages (C74) | |

| Loss of potency of cold chain medical supplies (C75) | |

| Irregular power supply and use of archaic technology in vaccine handling (C76) | |

| Inadequate ice blocks to maintain a cold chain (C77) | |

| Poor data management of medicines and vaccines supply (C8) | Poor procurement (C81) |

| Incomplete forecasting (C82) | |

| Poor data collection, use and management (C83) | |

| Poor reliability and availability of data for forecasting and decision making (C84) | |

| Sub-optimal data on vaccine stock (C85) | |

| Poor reliability and availability of data for forecasting and decision making (C86) |

| Linguistic Terms | Abbreviations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutely Low | AL | 0.1 | 0.975 |

| Very Low | VL | 0.15 | 0.9 |

| Low | L | 0.2 | 0.85 |

| Medium Low | ML | 0.35 | 0.7 |

| Medium | M | 0.5 | 0.45 |

| Medium High | MH | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| High | H | 0.7 | 0.35 |

| Very High | VH | 0.85 | 0.2 |

| Absolutely High | AH | 0.975 | 0.1 |

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | H | ML | VH | M | ML | M | ML |

| C12 | H | M | AL | AH | H | ML | H |

| C13 | H | M | H | M | ML | H | ML |

| C14 | VH | VL | VH | H | M | VH | VH |

| C15 | MH | AL | AL | AL | MH | M | L |

| C21 | VH | H | VL | H | MH | VL | M |

| C22 | AH | H | H | MH | VH | M | H |

| C31 | M | M | L | M | MH | L | MH |

| C32 | ML | AH | ML | L | H | ML | ML |

| C33 | MH | M | AL | M | L | L | L |

| C34 | MH | L | L | M | VH | H | ML |

| C41 | H | MH | L | L | ML | L | ML |

| C42 | L | L | L | L | AH | MH | L |

| C43 | L | ML | M | H | MH | M | ML |

| C51 | MH | ML | MH | VH | M | ML | MH |

| C52 | MH | H | ML | ML | M | ML | M |

| C53 | L | L | L | MH | ML | M | L |

| C54 | L | MH | L | ML | MH | MH | L |

| C61 | VH | MH | M | M | M | H | M |

| C62 | MH | ML | MH | ML | M | MH | MH |

| C63 | ML | ML | ML | H | ML | H | ML |

| C64 | VL | MH | VL | MH | AH | VL | VL |

| C71 | AH | VH | VH | M | VH | MH | VH |

| C72 | ML | M | MH | M | VH | M | ML |

| C73 | H | MH | MH | ML | H | MH | H |

| C74 | MH | H | MH | H | MH | M | MH |

| C75 | MH | MH | MH | H | AH | M | MH |

| C76 | MH | MH | VL | MH | VL | VL | VL |

| C77 | ML | H | ML | ML | ML | H | ML |

| C81 | VH | ML | ML | M | AH | ML | ML |

| C82 | MH | M | M | M | MH | H | MH |

| C83 | M | M | M | VL | M | M | M |

| C84 | MH | ML | MH | L | MH | ML | MH |

| C85 | H | ML | MH | VL | M | VH | MH |

| C86 | L | M | M | M | H | VL | H |

| C11 | 0.4857 | 0.4672 | C42 | 0.2934 | 0.5622 | C73 | 0.5935 | 0.4092 |

| C12 | 0.4798 | 0.3877 | C43 | 0.4266 | 0.5304 | C74 | 0.6109 | 0.3916 |

| C13 | 0.5216 | 0.4584 | C51 | 0.5267 | 0.4323 | C75 | 0.6405 | 0.3274 |

| C14 | 0.5982 | 0.3016 | C52 | 0.4621 | 0.5159 | C76 | 0.2717 | 0.6358 |

| C15 | 0.2318 | 0.6637 | C53 | 0.2889 | 0.6779 | C77 | 0.4267 | 0.5742 |

| C21 | 0.4321 | 0.4471 | C54 | 0.3469 | 0.5985 | C81 | 0.4840 | 0.4161 |

| C22 | 0.7035 | 0.2854 | C61 | 0.5809 | 0.3802 | C82 | 0.5673 | 0.4128 |

| C31 | 0.4054 | 0.5218 | C62 | 0.5011 | 0.4773 | C83 | 0.4210 | 0.4968 |

| C32 | 0.4130 | 0.4936 | C63 | 0.4267 | 0.5742 | C84 | 0.4397 | 0.5227 |

| C33 | 0.2753 | 0.6490 | C64 | 0.2912 | 0.5216 | C85 | 0.4771 | 0.4397 |

| C34 | 0.4249 | 0.4857 | C71 | 0.7645 | 0.2246 | C86 | 0.4066 | 0.5064 |

| C41 | 0.3284 | 0.6361 | C72 | 0.5000 | 0.4471 |

| Criteria | Score | Weight | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C71 | 1.3965 | - | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0465 |

| C22 | 1.2667 | 0.1298 | 1.1298 | 0.8851 | 0.0412 |

| C75 | 1.1556 | 0.1111 | 1.1111 | 0.7966 | 0.0370 |

| C14 | 1.1231 | 0.0325 | 1.0325 | 0.7716 | 0.0359 |

| C74 | 1.0747 | 0.0484 | 1.0484 | 0.7359 | 0.0342 |

| C61 | 1.0514 | 0.0232 | 1.0232 | 0.7192 | 0.0334 |

| C73 | 1.0416 | 0.0099 | 1.0099 | 0.7122 | 0.0331 |

| C82 | 1.0122 | 0.0294 | 1.0294 | 0.6918 | 0.0322 |

| C12 | 0.9601 | 0.0520 | 1.0520 | 0.6576 | 0.0306 |

| C51 | 0.9592 | 0.0009 | 1.0009 | 0.6570 | 0.0306 |

| C81 | 0.9402 | 0.0190 | 1.0190 | 0.6448 | 0.0300 |

| C13 | 0.9318 | 0.0084 | 1.0084 | 0.6394 | 0.0297 |

| C72 | 0.9251 | 0.0067 | 1.0067 | 0.6351 | 0.0295 |

| C85 | 0.9153 | 0.0098 | 1.0098 | 0.6290 | 0.0293 |

| C62 | 0.8980 | 0.0172 | 1.0172 | 0.6183 | 0.0288 |

| C11 | 0.8963 | 0.0018 | 1.0018 | 0.6172 | 0.0287 |

| C21 | 0.8808 | 0.0155 | 1.0155 | 0.6078 | 0.0283 |

| C34 | 0.8408 | 0.0399 | 1.0399 | 0.5844 | 0.0272 |

| C52 | 0.8326 | 0.0083 | 1.0083 | 0.5797 | 0.0270 |

| C83 | 0.8278 | 0.0048 | 1.0048 | 0.5769 | 0.0268 |

| C32 | 0.8267 | 0.0010 | 1.0010 | 0.5763 | 0.0268 |

| C84 | 0.8118 | 0.0150 | 1.0150 | 0.5678 | 0.0264 |

| C86 | 0.8108 | 0.0010 | 1.0010 | 0.5672 | 0.0264 |

| C43 | 0.7963 | 0.0144 | 1.0144 | 0.5592 | 0.0260 |

| C31 | 0.7943 | 0.0020 | 1.0020 | 0.5580 | 0.0260 |

| C64 | 0.7527 | 0.0417 | 1.0417 | 0.5357 | 0.0249 |

| C63 | 0.7479 | 0.0048 | 1.0048 | 0.5332 | 0.0248 |

| C77 | 0.7479 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.5332 | 0.0248 |

| C42 | 0.7092 | 0.0387 | 1.0387 | 0.5133 | 0.0239 |

| C54 | 0.6835 | 0.0257 | 1.0257 | 0.5005 | 0.0233 |

| C41 | 0.6308 | 0.0527 | 1.0527 | 0.4754 | 0.0221 |

| C76 | 0.6158 | 0.0150 | 1.0150 | 0.4684 | 0.0218 |

| C33 | 0.5997 | 0.0162 | 1.0162 | 0.4609 | 0.0214 |

| C15 | 0.5720 | 0.0277 | 1.0277 | 0.4485 | 0.0209 |

| C53 | 0.5646 | 0.0074 | 1.0074 | 0.4452 | 0.0207 |

| Alternative | Rank (Si) | Rank (Ri) | Rank (Qi) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.3917 | 0.0465 | 0.5000 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| A2 | 0.5589 | 0.0359 | 0.5082 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| A3 | 0.5931 | 0.0370 | 0.6378 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| A4 | 0.5242 | 0.0334 | 0.3289 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Alternative | FF-VIKOR | FF-TOPSIS | FF-SAW |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| A2 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| A3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| A4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Alternative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | −0.5000 | −0.244 | −0.229 | −0.301 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| A2 | −0.5082 | −0.248 | −0.723 | −0.827 | −0.659 | −0.434 |

| A3 | −0.6378 | −0.816 | −0.879 | −0.710 | −0.869 | −1.000 |

| A4 | −0.3289 | −0.887 | −0.401 | −0.127 | −0.470 | −0.390 |

| Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| Game value | –0.446196 |

| Guaranteed VIKOR level | 0.446196 |

| Row player (Policies) optimal mix | 0.790 0.210 0.000 |

| Column player (Scenarios) optimal mix | 0.686 0.314 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayyildiz, E.; Murat, M.; Ozcelik, G.; Kavus, B.Y.; Karaca, T.K. A Fermatean Fuzzy Game-Theoretic Framework for Policy Design in Sustainable Health Supply Chains. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223644

Ayyildiz E, Murat M, Ozcelik G, Kavus BY, Karaca TK. A Fermatean Fuzzy Game-Theoretic Framework for Policy Design in Sustainable Health Supply Chains. Mathematics. 2025; 13(22):3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223644

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyyildiz, Ertugrul, Mirac Murat, Gokhan Ozcelik, Bahar Yalcin Kavus, and Tolga Kudret Karaca. 2025. "A Fermatean Fuzzy Game-Theoretic Framework for Policy Design in Sustainable Health Supply Chains" Mathematics 13, no. 22: 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223644

APA StyleAyyildiz, E., Murat, M., Ozcelik, G., Kavus, B. Y., & Karaca, T. K. (2025). A Fermatean Fuzzy Game-Theoretic Framework for Policy Design in Sustainable Health Supply Chains. Mathematics, 13(22), 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223644