A Vectorization Approach to Solving and Controlling Fractional Delay Differential Sylvester Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- Explicit representation formulas for the solution of (2) under both permutable and non-permutable assumptions on the coefficient matrices, utilizing a delayed perturbation of a two-parameter Mittag-Leffler-type matrix function adapted to the Sylvester structure, and generalizing and improving the corresponding results in [38].

- (ii)

- (iii)

- A constructive methodology based on Kronecker product transformations, delayed matrix function expansions, and vectorization techniques, enabling both theoretical analysis and numerical implementation.

- (iv)

- The derived results not only improve and generalize the existing literature on scalar and vector delay systems but also provide foundational tools for the control and stabilization of large-scale matrix dynamical systems arising in multi-agent networks, tensor-based models, and coupled PDE-ODE systems with memory.

2. Preliminaries

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- ;

- 3.

- .

3. Exact Solutions of a Fractional Delay Differential Matrix Equation

4. Controllability

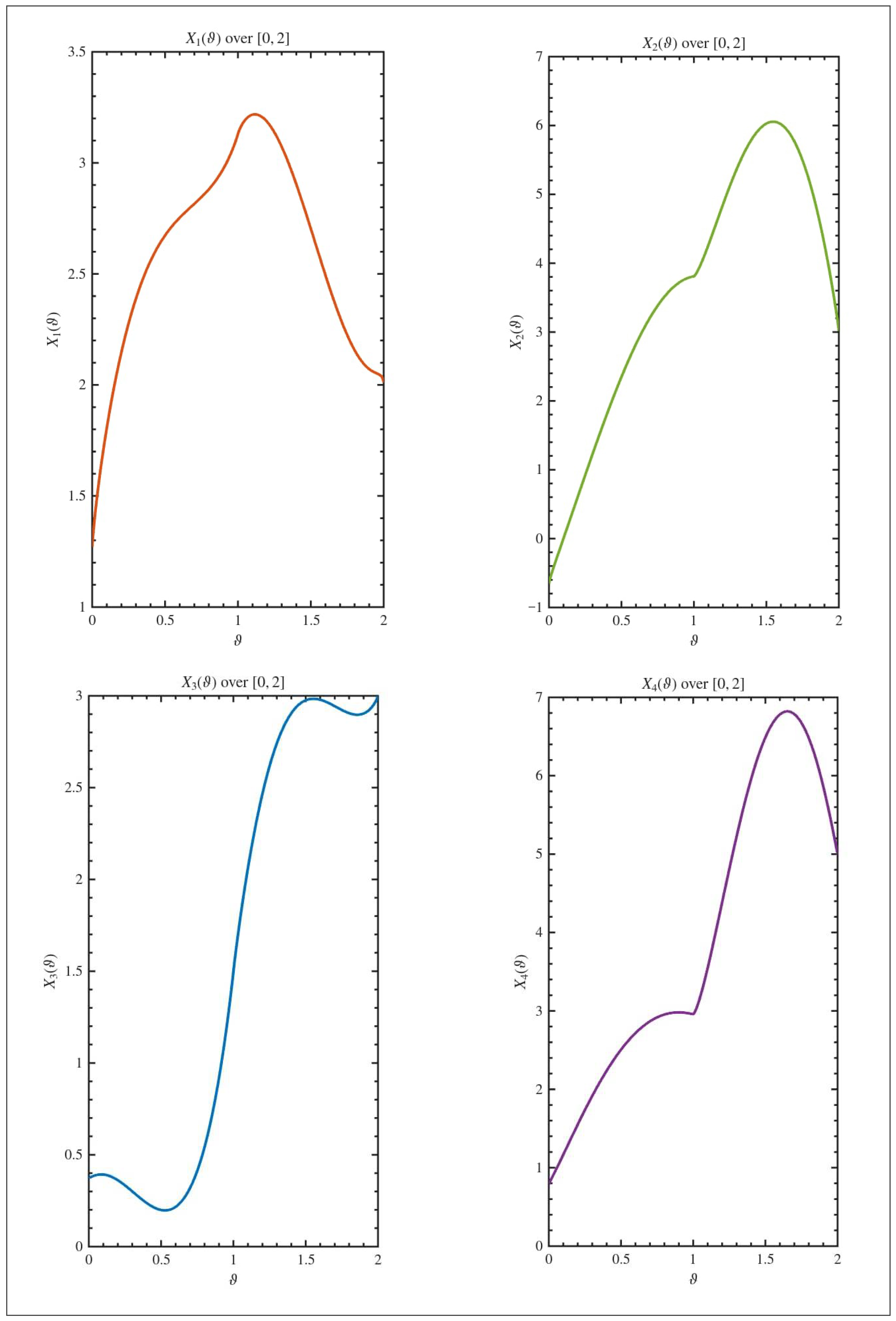

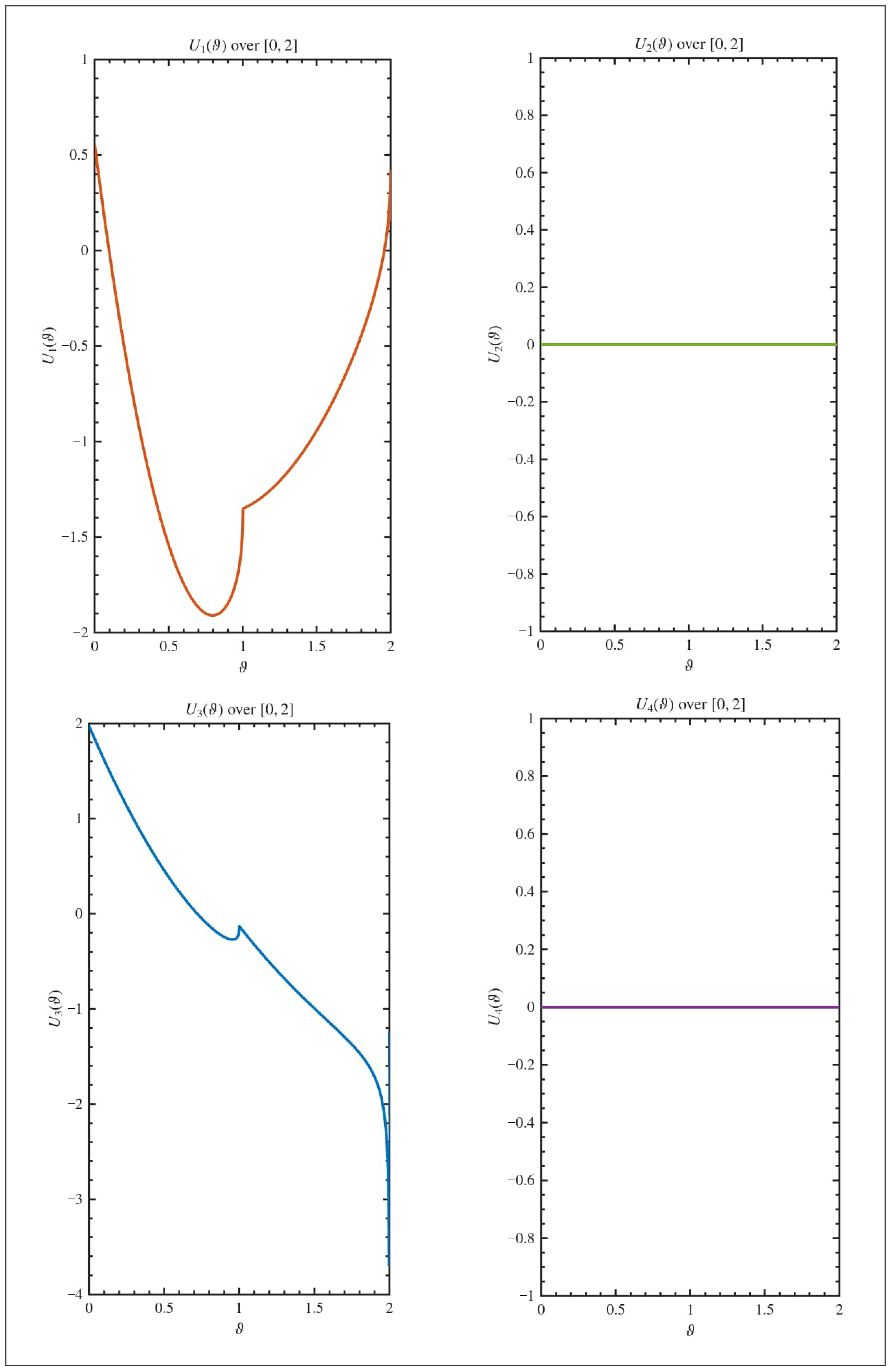

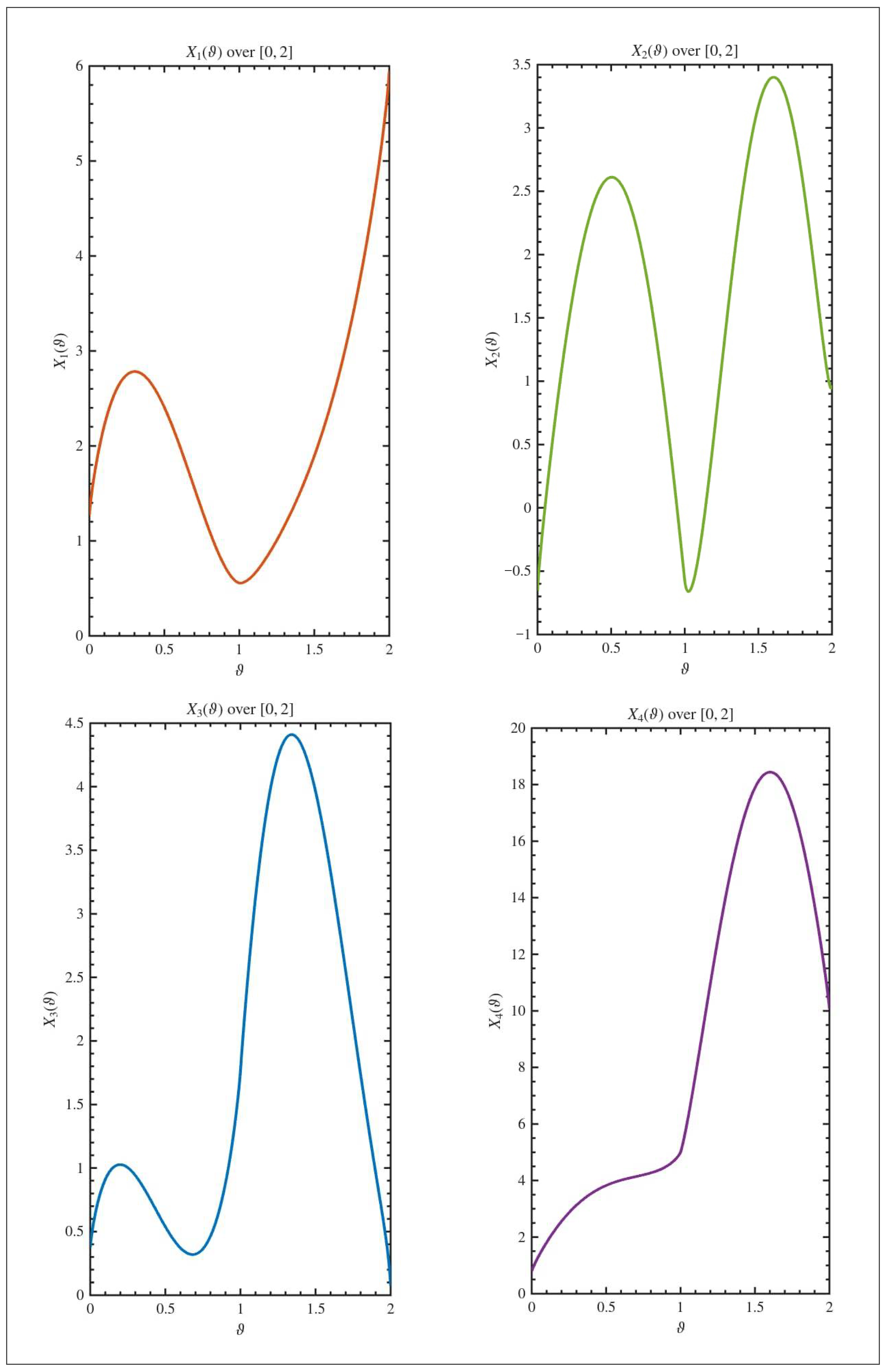

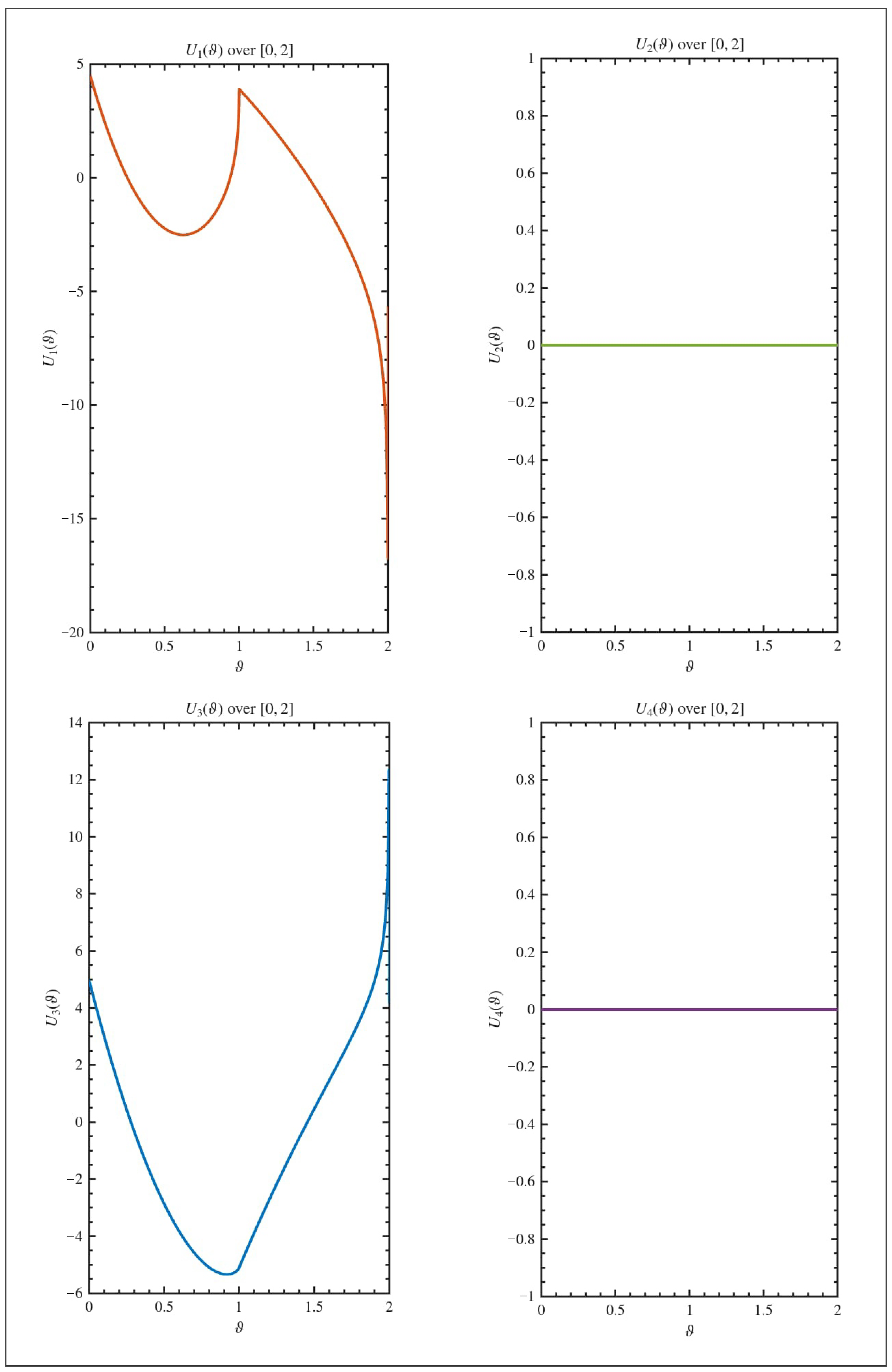

5. An Example

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coimbra, C.F.M. Mechanics with variable-order differential operators. Ann. Phys. 2003, 12, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K. The Analysis of Fractional Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, N.; Podlubny, I. Physical interpretation of initial conditions for fractional differential equations with Riemann-Liouville fractional derivatives. Rheol. Acta 2006, 45, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier Science BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obembe, A.D.; Hossain, M.E.; Abu-Khamsin, S.A. Variable-order derivative time fractional diffusion model for heterogeneous porous media. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 152, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweilam, N.H.; Al-Mekhlafi, S.M. Numerical study for multi-strain tuberculosis (TB) model of variable-order fractional derivatives. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasov, V. Handbook of Fractional Calculus with Applications: Applications in Physics, Part A; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Rakshit, M.; Manivel, M.; Shyamsunder. Modeling of Hepatitis B Virus Transmission with Vaccination, Treatment, and Memory Effects. Adv. Theory Simul. 2025, 7, e01358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshenhab, A.M.; Wang, X.T.; Hosny, M. Explicit solutions and finite-time stability for fractional delay systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 498, 129388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusainov, D.Y.; Diblík, J.; Růžičková, M.; Lukáčová, J. A representation of the solution of the Cauchy problem for an oscillatory system with pure delay. Nonlinear Oscil. 2008, 11, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusainov, D.Y.; Shuklin, G.V. Linear autonomous time-delay system with permutation matrices solving. Math. Ser. 2003, 17, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudov, N.I. A novel fractional delayed matrix cosine and sine. Appl. Math. Lett. 2019, 92, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshenhab, A.M.; Wang, X.T. Representation of solutions for linear fractional systems with pure delay and multiple delays. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2021, 44, 12835–12850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, N.I. Multi-delayed perturbation of Mittag-Leffler type matrix functions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2022, 505, 125589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, N.I. Delayed perturbation of Mittag-Leffler functions and their applications to fractional linear delay differential equations. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2019, 42, 5489–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi Priya, P.K.; Kaliraj, K. A study on the finite time stability and controllability of time delay fractional model. Arab. J. Math. 2025, 14, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, B.; Wang, X.; Elshenhab, A.M. Controllability and Hyers–Ulam stability of fractional systems with pure delay. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Mahmudov, N.I. Iterative learning control for impulsive fractional order time-delay systems with nonpermutable constant coefficient matrices. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2022, 36, 1419–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Mahmudov, N.I. On a study for the neutral Caputo fractional multi-delayed differential equations with noncommutative coefficient matrices. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 161, 112372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, F.-R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S. Active vibration control of typical piping system of a nuclear power plant based on fractional PI controller. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 2111–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, S.S.; Swain, D.R.; Rout, P.K. Inter-area and intra-area oscillation damping for UPFC in a multi-machine power system based on tuned fractional PI controllers. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 1594–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wu, Z. Cluster synchronization of fractional-order directed networks via intermittent pinning control. Phys. A 2019, 519, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Samanta, G. Optimal control of a fractional order epidemic model with carriers. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazza, L.; Mourillon, B.; Makhlouf, A.; Birouche, A. Controllability and observability of formal perturbed linear time invariant systems. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2021, 9, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjerida, A.; Seba, D. Controllability of nonlocal Hilfer fractional delay dynamic inclusions with non-instantaneous impulses and non-dense domain. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 1613–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuzy, M.; Shamaghdari, S. Stability analysis of fractional-order linear system with PID controller in the output feedback structure subject to input saturation. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, M.; Appa, R.B.; Suresh, K.G. Controllability, observability, and realizability of matrix Lyapunov systems. Bull. Korean Math. Soc. 2006, 43, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appa Rao, B.V.; Prasad, K.A.S.N.Y. Controllability and observability of Sylvester matrix dynamical systems on time scales. Kyungpook Math. J. 2016, 56, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, B.; George, R.K. Controllability of semilinear matrix Lyapunov systems. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2013, 2013, 1–12. Available online: http://ejde.math.txstate.edu (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Dubey, B.; George, R.K. Controllability of impulsive matrix Lyapunov systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 254, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Pandey, D.N. Controllability of fractional impulsive quasilinear differential systems with state dependent delay. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2019, 7, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, L.; Abouzaid, B.; Sadek, E.M.; Alaoui, H.T. Controllability, observability and fractional linear-quadratic problem for fractional linear systems with conformable fractional derivatives and some applications. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2023, 11, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, L. Control theory for fractional differential Sylvester matrix equations with Caputo fractional derivative. J. Vib. Control 2025, 31, 1586–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuchta, T.; Poulsen, D.; Wintz, N. Linear quadratic tracking with continuous conformable derivatives. Eur. J. Control 2023, 72, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corless, M.J.; Frazho, A.E. Linear Systems and Control: An Operator Perspective; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/32303/1/91.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Hale, J.K.; Verduyn Lunel, S.M. Introduction to Functional-Differential Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmanovskii, V.; Myshkis, A. Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Functional Differential Equations; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diblík, J. Representation of solutions to a linear matrix first-order differential equation with delay. Bull. Math. Sci. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A. Kronecker Products and Matrix Calculus with Applications; Ellis Horwood Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1981; Available online: https://pdfcoffee.com/alexander-graham-kronecker-products-and-matrix-calculus-with-applications-pdf-free.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Wang, J.; Luo, Z.; Fečkan, M. Relative controllability of semilinear delay differential systems with linear parts defined by permutable matrices. Eur. J. Control 2017, 38, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hached, M.; Jbilou, K. Computational Krylov-based methods for large-scale differential Sylvester matrix problems. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2018, 25, e2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, E.M.; Bentbib, A.H.; Sadek, L.; Talibi Alaoui, H. Global extended Krylov subspace methods for large-scale differential Sylvester matrix equations. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 62, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mofarreh, F.; Elshenhab, A.M. A Vectorization Approach to Solving and Controlling Fractional Delay Differential Sylvester Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223631

Mofarreh F, Elshenhab AM. A Vectorization Approach to Solving and Controlling Fractional Delay Differential Sylvester Systems. Mathematics. 2025; 13(22):3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223631

Chicago/Turabian StyleMofarreh, Fatemah, and Ahmed M. Elshenhab. 2025. "A Vectorization Approach to Solving and Controlling Fractional Delay Differential Sylvester Systems" Mathematics 13, no. 22: 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223631

APA StyleMofarreh, F., & Elshenhab, A. M. (2025). A Vectorization Approach to Solving and Controlling Fractional Delay Differential Sylvester Systems. Mathematics, 13(22), 3631. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223631