Implementing the Linear Adaptive False Discovery Rate Procedure for Spatiotemporal Trend Testing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Foundations of FDR

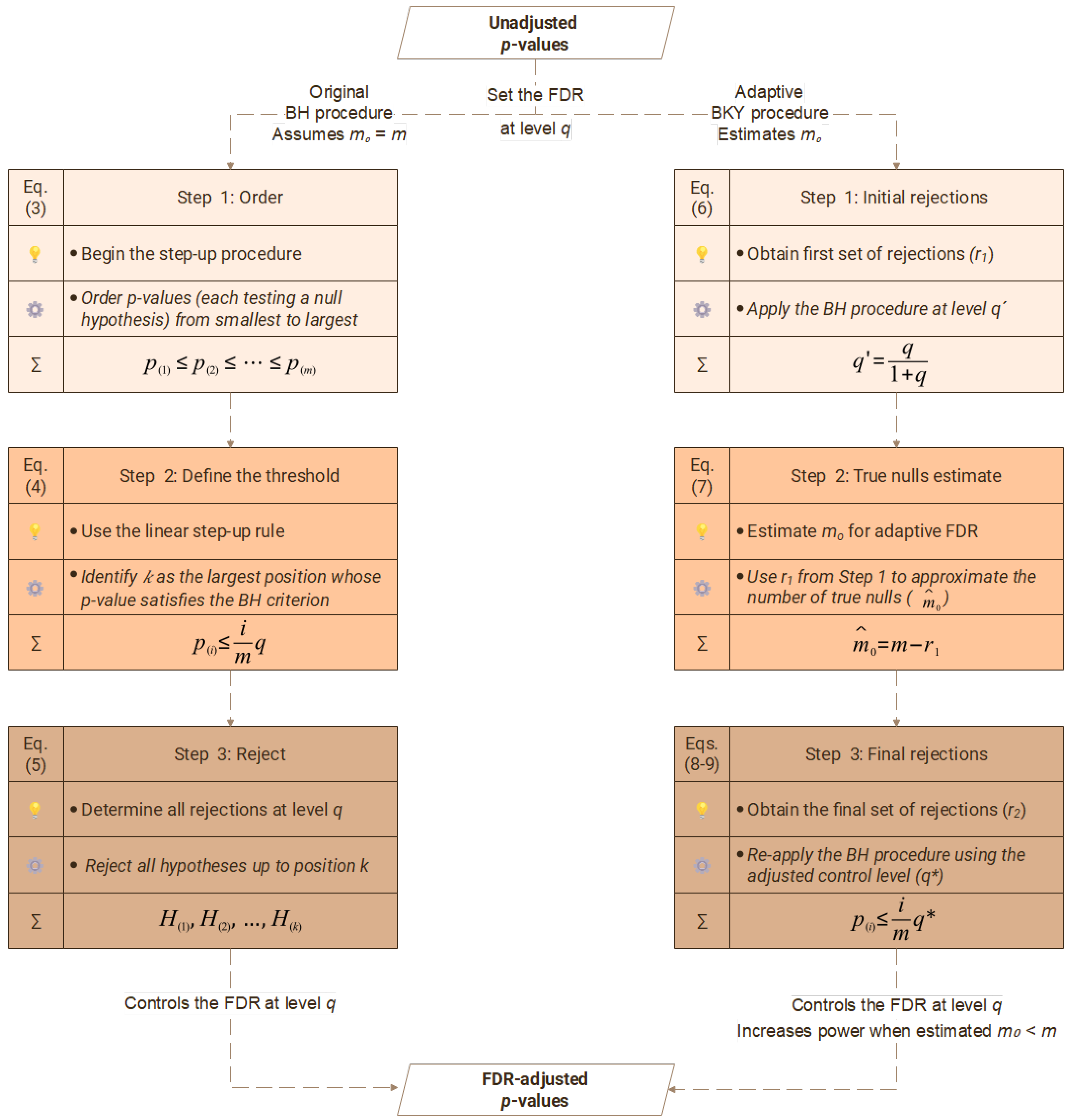

2.2. Procedures for FDR Control

2.2.1. The Benjamini–Hochberg Procedure (BH)

- Step 1. Order the p-values of all the hypothesis tests in ascending order (Equation (3)):

- Step 2. Identify as the largest value of such that (Equation (4)):

- Step 3. The final step is to reject all null hypotheses corresponding to p-values up to position k (Equation (5)):

2.2.2. The Benjamini-Krieger-Yekutieli Procedure (BKY)

- Step 1. Apply the linear step-up BH procedure at a reduced significance level q′, defined as (Equation (6)):

- If : no hypothesis is rejected, and the procedure stops.

- If : all hypotheses are rejected, and the procedure stops.

- Otherwise, proceed to Step 2.

- Step 2. Use the complement to to obtain a conservative estimate of the number of true null hypotheses (), as shown in (Equation (7)):

- Step 3. Apply the linear step-up BH procedure again, using the adjusted significance level (Equation (8)):

2.2.3. Features and Advantages of FDR Control

2.3. Application: From a Limited Dataset to a Real Case Study

2.4. Software Implementation and Reproducibility

3. Results

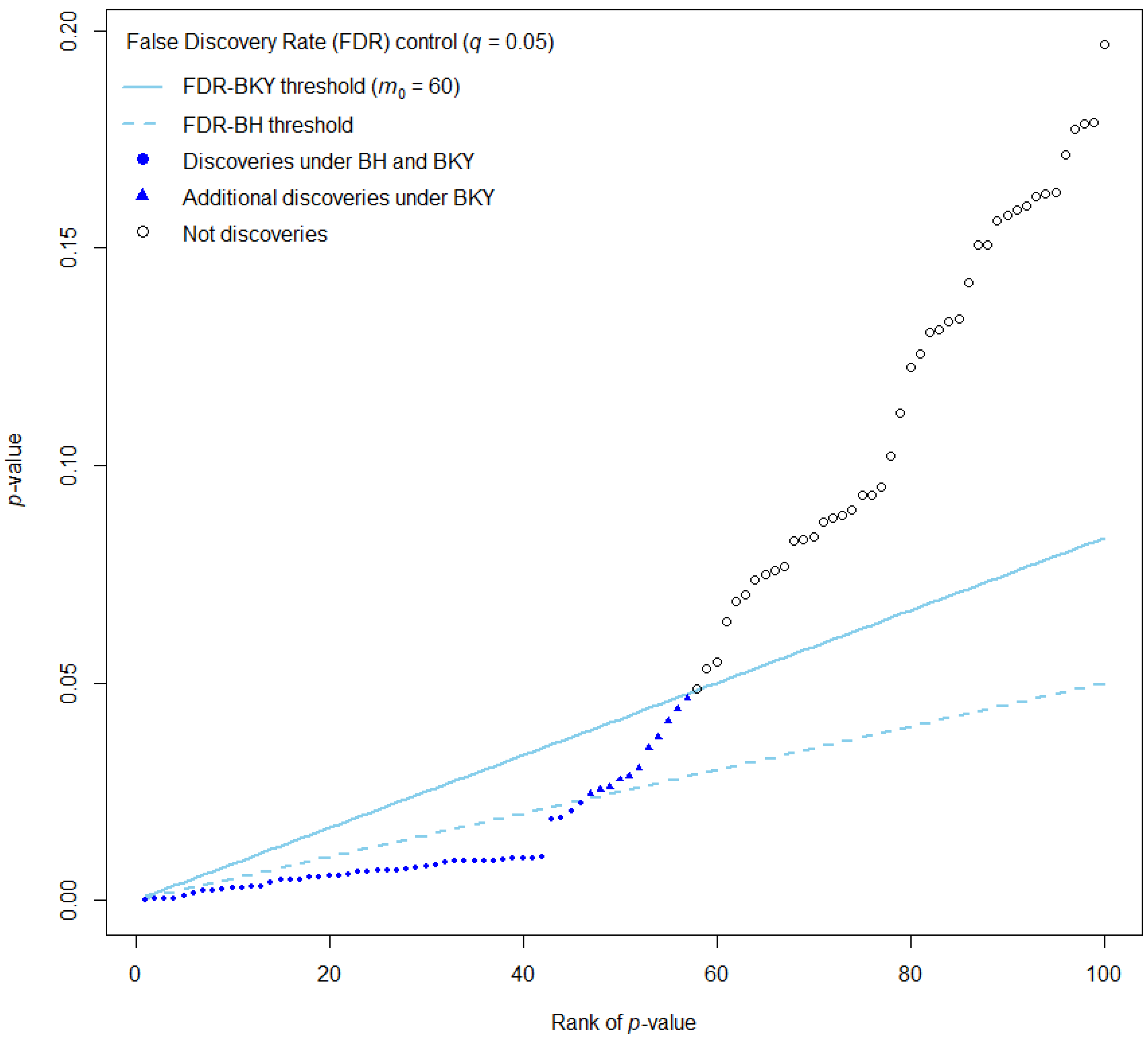

3.1. Limited Dataset: Graphical Comparison of p-Value Rejection Thresholds

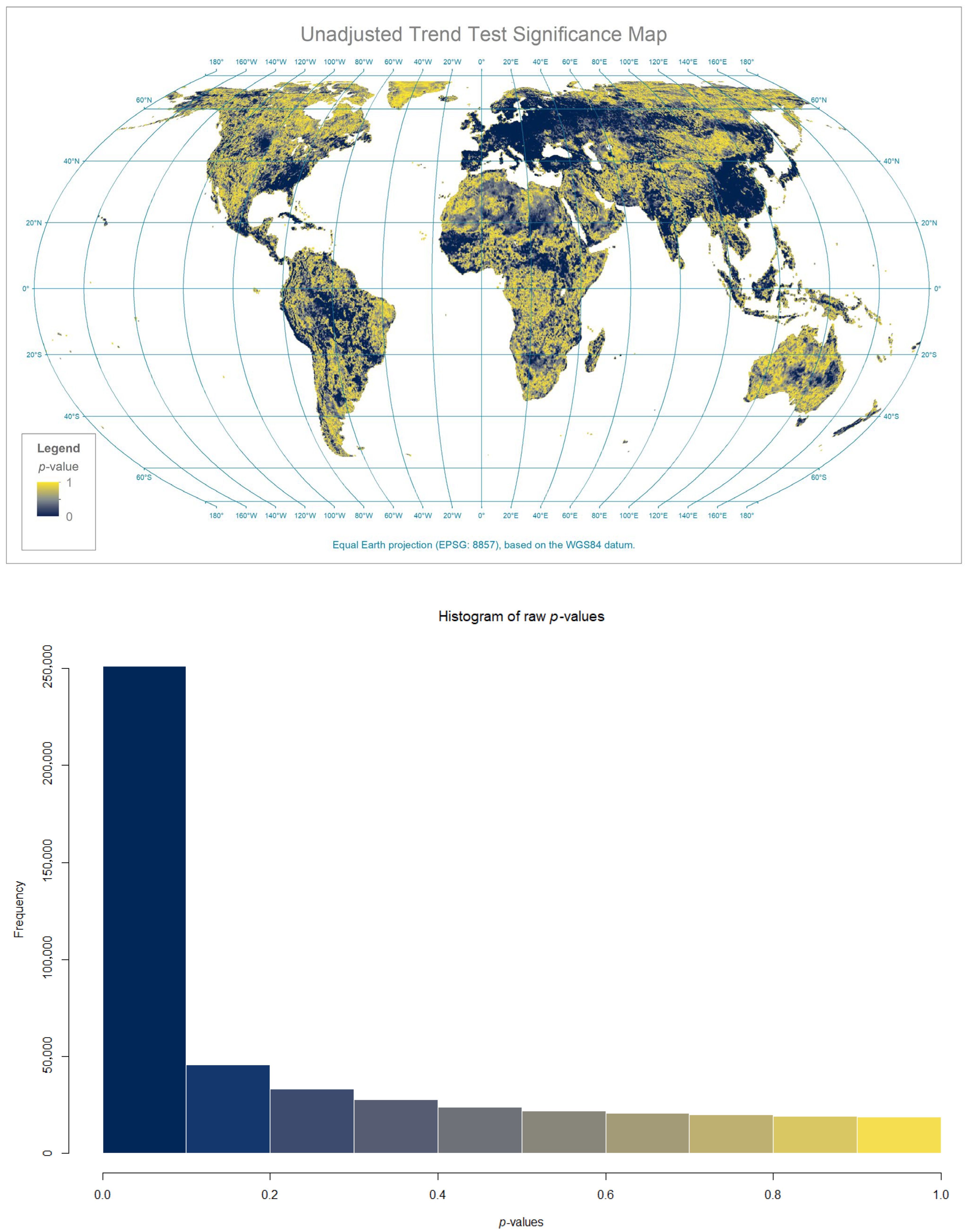

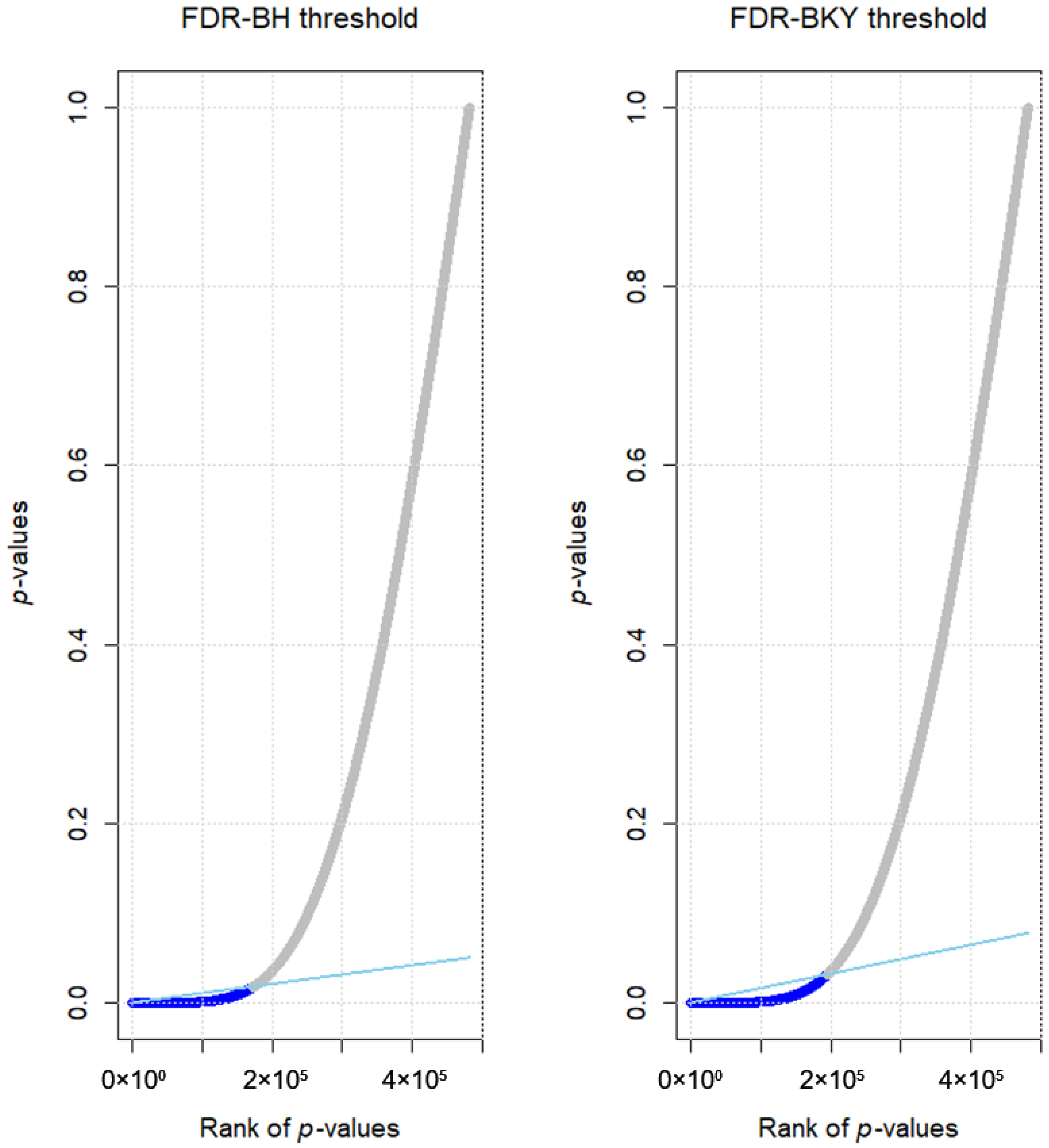

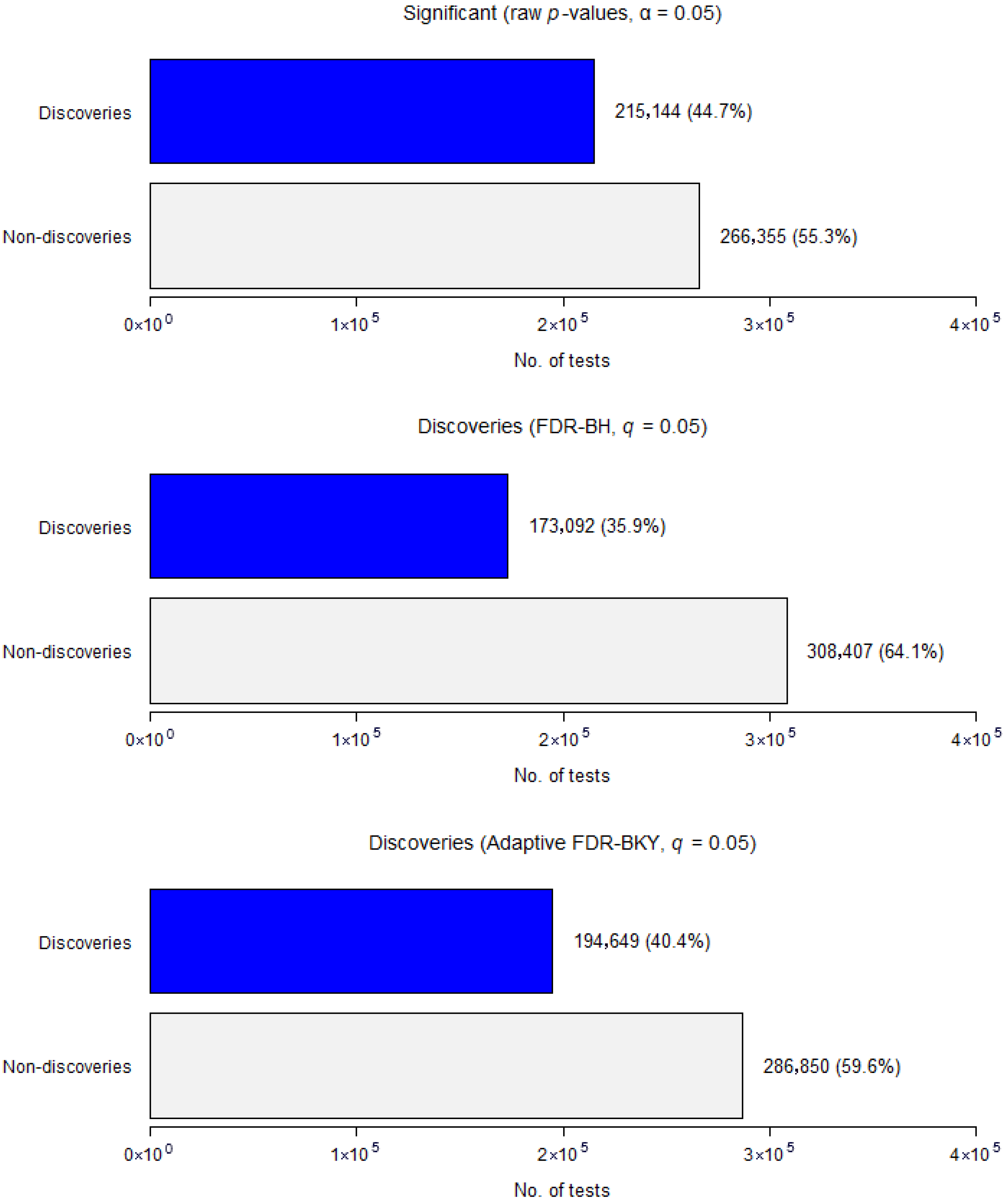

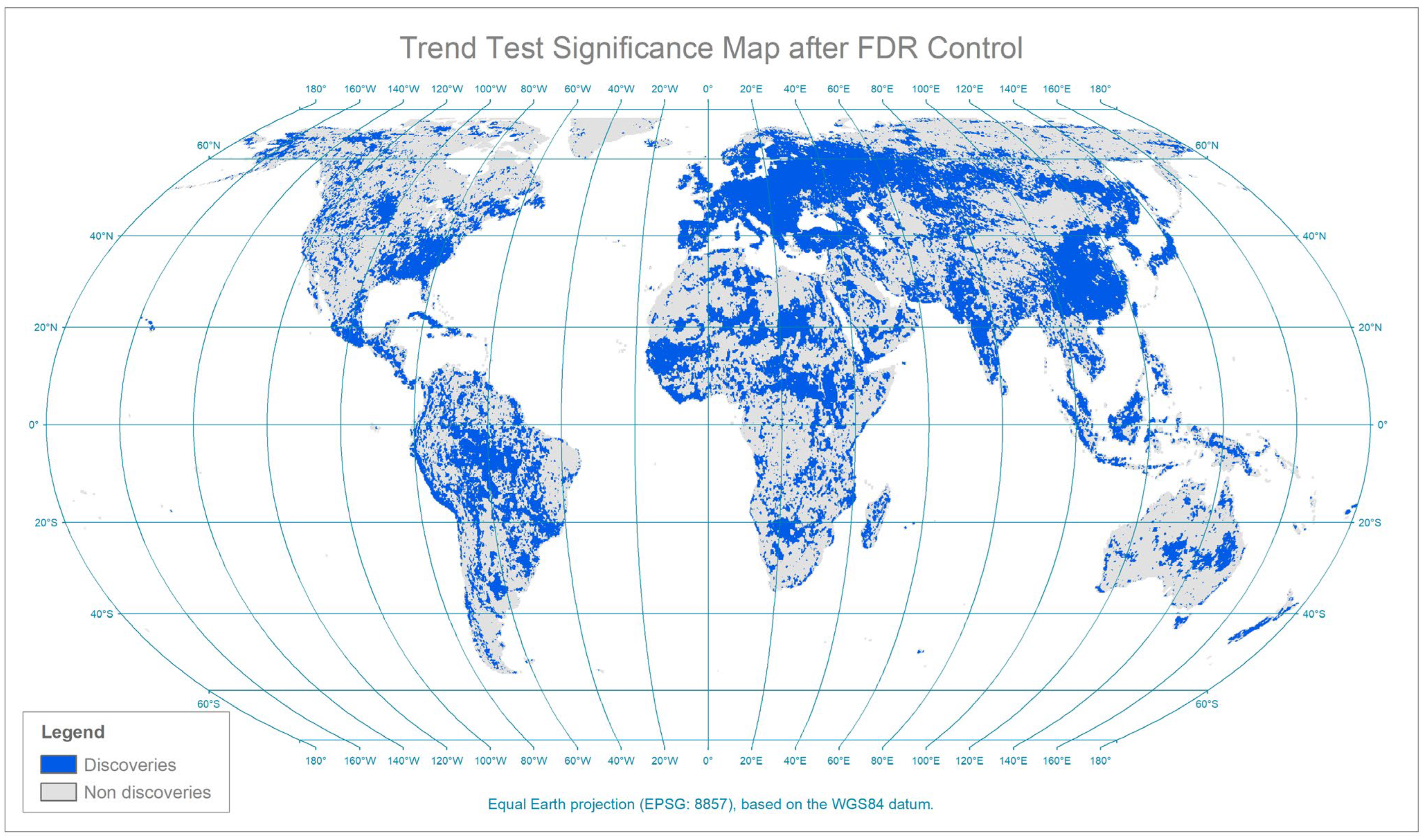

3.2. Real Case Study: From Raw p-Values to FDR-Adjusted Discoveries

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of FDR Control and the Adaptive Approach

4.2. FDR Control Under Dependence

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| AVHRR | Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for FDR control |

| BKY | Benjamini–Krieger–Yekutieli procedure for adaptive FDR control |

| BR | Blanchard and Roquain procedure for adaptive FDR control |

| BY | Benjamini–Yekutieli procedure for FDR control |

| CMK | Contextual Mann–Kendall trend test |

| EPSG | European Petroleum Survey Group (spatial reference codes, e.g., EPSG:4326 for WGS84) |

| ETM | Earth Trends Modeller |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GeoTIFF | Georeferenced Tagged Image File Format |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| LZW | Lempel–Ziv–Welch (compression algorithm) |

| NDVI | Normalised Difference Vegetation Index |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (United States of America) |

References

- Cortés, J.; Mahecha, M.; Reichstein, M.; Brenning, A. Accounting for Multiple Testing in the Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Environmental Data. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2020, 27, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. Selective Inference: The Silent Killer of Replicability. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. The Ghost of Selective Inference in Spatiotemporal Trend Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 177832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, L.V. Escaping the Bonferroni Iron Claw in Ecological Studies. Oikos 2004, 105, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. Discovering the False Discovery Rate. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2010, 72, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 89–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorden, R.; Maher, B.; Nuzzo, R. The Top 100 Papers. Nature 2014, 514, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noorden, R. These Are the Most-Cited Research Papers of All Time. Nature 2025, 640, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, N.; Sarkar, S.K.; Zhao, Z.; Kim, D.-Y. Applying Multiple Testing Procedures to Detect Change in East African Vegetation. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2014, 8, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heumann, B.W. The Multiple Comparison Problem in Empirical Remote Sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2015, 81, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. False Discovery Rate Estimation and Control in Remote Sensing: Reliable Statistical Significance in Spatially Dependent Gridded Data. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 16, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. Trends in Vegetation Seasonality in the Iberian Peninsula: Spatiotemporal Analysis Using AVHRR-NDVI Data (1982–2023). Sustainability 2024, 16, 9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. Robust Trend Analysis in Environmental Remote Sensing: A Case Study of Cork Oak Forest Decline. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Hernández, O.; García, L.V. Multiple Testing in Remote Sensing: Addressing the Elephant in the Room. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Krieger, A.M.; Yekutieli, D. Adaptive Linear Step-up Procedures That Control the False Discovery Rate. Biometrika 2006, 93, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.G. Simultaneous Statistical Inference; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-1-4613-8124-2. [Google Scholar]

- Farcomeni, A. Some Results on the Control of the False Discovery Rate under Dependence. Scand. J. Stat. 2007, 34, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeman, J.J.; Solari, A. Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Genomics. Stat. Med. 2014, 33, 1946–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Large-Scale Inference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780521192491. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Yekutieli, D. The Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing under Dependency. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1165–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthauer, K.; Kimes, P.K.; Duvallet, C.; Reyes, A.; Subramanian, A.; Teng, M.; Shukla, C.; Alm, E.J.; Hicks, S.C. A Practical Guide to Methods Controlling False Discoveries in Computational Biology. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, A.; Zhang, T. On the False Discovery Rates of a Frequentist: Asymptotic Expansions. In Recent Developments in Nonparametric Inference and Probability; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Beachwood, OH, USA, 2006; pp. 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kileen, P.R. Beyond Statistical Inference: A Decision Theory for Science. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.; Storey, J.D.; Tusher, V. Empirical Bayes Analysis of a Microarray Experiment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001, 96, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.D. The Positive False Discovery Rate: A Bayesian Interpretation and the q-Value. Ann. Stat. 2003, 31, 2013–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.; Wasserman, L. A Stochastic Process Approach to False Discovery Control. Ann. Stat. 2004, 32, 1035–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Genovese, C.; Nichol, R.C.; Wasserman, L.; Connolly, A.; Reichart, D.; Hopkins, A.; Schneider, J.; Moore, A. Controlling the False-Discovery Rate in Astrophysical Data Analysis. Astron. J. 2001, 122, 3492–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. “The Stippling Shows Statistically Significant Grid Points”: How Research Results Are Routinely Overstated and Overinterpreted, and What to Do about It. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2016, 97, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. On “Field Significance” and the False Discovery Rate. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2006, 45, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, V.; Paciorek, C.J.; Risbey, J.S. Controlling the Proportion of Falsely Rejected Hypotheses When Conducting Multiple Tests with Climatological Data. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 4343–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeti, N.; Ronald Eastman, J. Novel Approaches in Extended Principal Component Analysis to Compare Spatio-Temporal Patterns among Multiple Image Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Wang, C.Y. Applicability of Prewhitening to Eliminate the Influence of Serial Correlation on the Mann-Kendall Test. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 4-1–4-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Greenwave Effect) of Natural Vegetation; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 1974; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Roerink, G.J.; Menenti, M.; Verhoef, W. Reconstructing Cloudfree NDVI Composites Using Fourier Analysis of Time Series. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forthofer, R.N.; Lee, E.S.; Hernandez, M. Descriptive Methods. In Biostatistics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 21–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, W.R. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A.P. Notes on Continuous Stochastic Phenomena. Biometrika 1950, 37, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J. TerrSet: Geospatial Monitoring and Modeling Software, Version 20; ClarkLabs: Worcester, MA, USA, 2024.

- Šavrič, B.; Patterson, T.; Jenny, B. The Equal Earth Map Projection. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Gianetto, Q.; Combes, F.; Ramus, C.; Bruley, C.; Couté, Y.; Burger, T. Cp4p: Calibration Plot for Proteomics; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, K.S.; Dudoit, S.; van der Laan, M.J. Multiple Testing Procedures: The Multtest Package and Applications to Genomics. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, K.; Gilberrt, H.; Ge, Y.; Taylor, S.; Dudoit, S. Multtest, Version 2.58; Resampling-Based Multiple Hypothesis Testing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- Hijmans, R. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Getis, A.; Cliff, A.D.; Ord, J.K. 1973: Spatial Autocorrelation. London: Pion. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1995, 19, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliff, A.; Ord, J. Spatial Autocorrelation; Pion: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Neeti, N.; Eastman, J.R. A Contextual Mann-Kendall Approach for the Assessment of Trend Significance in Image Time Series. Trans. GIS 2011, 15, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.R.; Lazar, N.A.; Nichols, T. Thresholding of Statistical Maps in Functional Neuroimaging Using the False Discovery Rate. Neuroimage 2002, 15, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.P.; Shaikh, A.M.; Wolf, M. Control of the False Discovery Rate under Dependence Using the Bootstrap and Subsampling. TEST 2008, 17, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, G.; Roquain, E. Adaptive False Discovery Rate Control under Independence and Dependence. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 2837–2871. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. Uncovering True Significant Trends in Global Greening. Remote Sens. Appl. 2025, 37, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasiak, N.; Dejoux, J.-F.; Monteil, C.; Sheeren, D. Spatial Dependence between Training and Test Sets: Another Pitfall of Classification Accuracy Assessment in Remote Sensing. Mach. Learn. 2022, 111, 2715–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, A.R.; Zhu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhu, J.; Morrow, C.J.; Radeloff, V.C. Statistical Inference for Trends in Spatiotemporal Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 266, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, G.; Roquain, E. Two Simple Sufficient Conditions for FDR Control. Electron. J. Stat. 2008, 2, 963–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekutieli, D.; Benjamini, Y. Resampling-Based False Discovery Rate Controlling Multiple Test Procedures for Correlated Test Statistics. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1999, 82, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Heller, R. False Discovery Rates for Spatial Signals. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2007, 102, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H0 Not Rejected | H0 Rejected | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H0 True | N0|0 U (true negatives) | N1|0 V (false positives) Type I errors | m0 (True null hypotheses) |

| H0 False | N0|1 T (false negatives) Type II errors | N1|1 S (true positives) | m1 (False null hypotheses) |

| Total | m–R (Non-rejections) | R = V + S (Rejections) | m (Total tests) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Hernández, O.; García, L.V. Implementing the Linear Adaptive False Discovery Rate Procedure for Spatiotemporal Trend Testing. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3630. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223630

Gutiérrez-Hernández O, García LV. Implementing the Linear Adaptive False Discovery Rate Procedure for Spatiotemporal Trend Testing. Mathematics. 2025; 13(22):3630. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223630

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez-Hernández, Oliver, and Luis V. García. 2025. "Implementing the Linear Adaptive False Discovery Rate Procedure for Spatiotemporal Trend Testing" Mathematics 13, no. 22: 3630. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223630

APA StyleGutiérrez-Hernández, O., & García, L. V. (2025). Implementing the Linear Adaptive False Discovery Rate Procedure for Spatiotemporal Trend Testing. Mathematics, 13(22), 3630. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13223630