2.1. Probabilistic Graphical Models

Probabilistic Graphical Models (PGMs, [

13]) are suited to represent multivariate contexts where the decomposition of the joint probability density function (PDF) into the product of conditional probability density functions is characterized by a small number of conditioning variables within each factor. In the context

, a set of variables

is considered, and the joint distribution is written as follows:

where

is the set of variables required in the conditional PDF of

.

A directed acyclic graph (DAG),

, is a qualitative representation of conditional independence (C.I.) relationships where

V is the set of vertices, also called nodes, and

E is the set of directed edges joining distinct nodes. The qualitative representation of Equation (

1) is obtained by setting

and by introducing a directed edge into

E for each conditioning variable (parent) in

joining

(child), with

. An equivalent explicit notation for parents is

, with a total of

parent nodes for

in the DAG. In

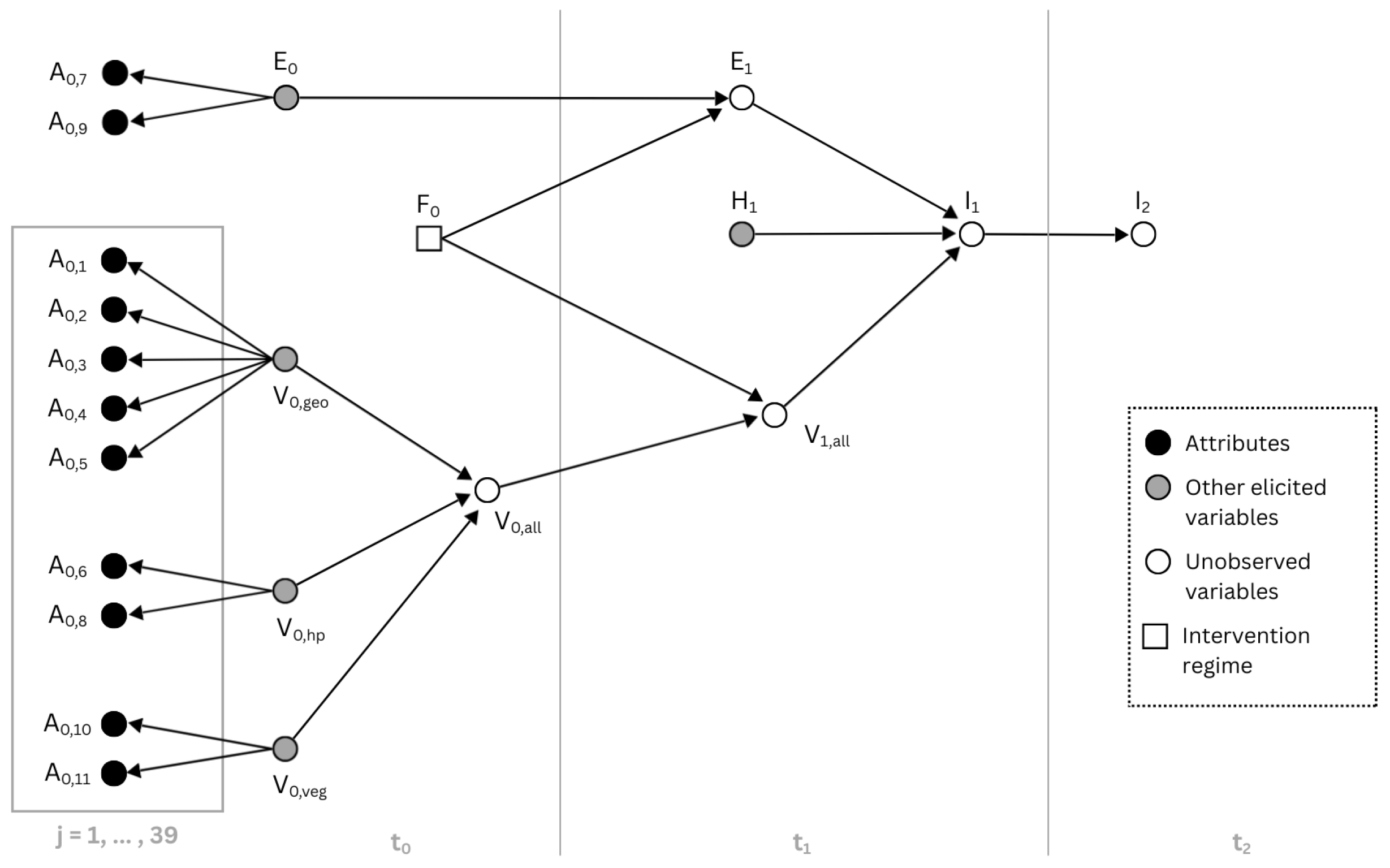

Figure 1,

is a variable with parent nodes

equal to

,

and

. Although 22 variables are considered, this DAG is sparse, i.e., the number of directed edges is low: the resulting models are often less cognitively demanding to humans, helping to avoid a premature detachment of human intuition from the context [

13]. A color-enhanced version of the DAG shown in

Figure 1 is available in the

Supplementary Materials (file “DAG drawing v4 color.png”).

DAGs are also useful to describe causal relationships, and in this setup, a directed edge from

to

indicates a direct causal relationship from a variable representing hazard to a variable representing impact (see [

14], for an introduction). In the class of structural causal models (SCM), each causal relationship is a deterministic function as follows:

where parents of node

,

, are endogenous variables representing direct causes of

; the implicit function

also depends on the exogenous variable

, which accounts for all other causal factors not explicitly considered in the current model. The Markovian assumption on the joint distribution of

characterizes many useful models as follows:

thus, exogenous variables are marginally independent. It is worth noting that some inferential tasks may be equally performed after integrating out all the exogenous variables to obtain a causal Bayesian network (BN), where each variable (but

) has a PDF.

Most of the vertices defined in this study are discrete ordinal random variables, thus they take 2, 3, or 5 ordered values; for example, a five-level sample space may be defined as

= {“Very Low”, “Low”, “Medium”, “High”, “Very High”}, and it is often represented by integers

[

15]. The conditional PDFs are also discrete, and the vector (or matrix) of the parameters

refers to the conditional pdfs for the random variable

. The collection of all model parameters is indicated as

.

Parameter learning in the graphical model considered here is performed according to Bayes’ theorem. The likelihood function of model parameters is, with just one observation, as follows:

A special class of prior PDFs for parameters of categorical variables deserves to be mentioned—the Dirichlet family. We simplify the notation a bit by omitting the index

j, while describing the Dirichlet prior distribution

, where the sample space of

is

. For vectors

and

we say that pi follows the Dirichlet distribution

if

and where

.

The final (posterior) distribution after conditioning to

n exchangeable vectors

is as follows:

thus, the initial PDF of

is made by marginally independent vectors,

; the omitted normalizing factor is

. If all variables are categorical and for each pair

vectors

for the configuration of parents

are independent with pdf in the Dirichlet family, then the posterior distributions are also Dirichlet (with complete data): the final hyperparameters lambda are obtained adding to

the observed counts in class

k of

, e.g., with no parents

.

2.2. The Calabrian Coastal Case Study

The R package

vulneraR deals with a minimal but not-trivial context located in the Calabrian coast.

Figure 1 illustrates the main features through an annotated DAG, in which each vertex-variable is assigned to one of the subsequent time intervals (

,

, and

), delimited by vertical gray lines. The length of the intervals is context-specific: the period

must be sufficiently long to allow the occurrence of the event of interest (the hazard), yet not so long that the assessments or assumptions regarding the attributes and variables measured in

,

, and

lose validity or temporal relevance. When working with the hazard variable, we refer to the definition by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC,

https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/chapter/glossary/, accessed on 4 August 2025): “The potential occurrence of a natural or human-induced physical event or trend that may cause loss of life, injury, or other health impacts, as well as damage and loss to property, infrastructure, livelihoods, service provision, ecosystems, and environmental resources. See also Disaster, Exposure, Loss and Damage, and losses and damages, Risk and Vulnerability.” In our context, dealing with the Calabrian coasts, the expert stated that the three time intervals could each be two years long. It is worth noting that the scale is expressed in months rather than days or hours, since a higher level of detail is not required at the considered model granularity.

The plate [

16] on the left, in general, contexts may contain eleven variables [

1], because sampled transects

each contribute the same set of eleven variables. However, during the elicitation of distributions with our expert (see

Section 2.3), the DAG was refined by making attributes

(“Relative Sea Level Change”) and

(“Mean Tide Range”) children of the Exposure node,

. Since these two hydro-physical attributes are not site-specific and remain spatially uniform across the study area, they are more informative for assessing exposure than vulnerability.

We note in passing that if

then in

Figure 1 the PGM corresponds to a discrete Bayesian network, see [

17]. Last, our context

is characterized by unobserved variables, that is,

and all variables located in time intervals greater than

: future global vulnerability, exposure, hazard, and impacts.

The eleven attributes in

Figure 1 are detailed in [

1], and they are grouped according to different types of vulnerability, as summarized in

Table 1. The overall vulnerability

depends on sub-vulnerability indices

, and it may change in the next time interval

into

, as described in the next section. Similarly, in

Figure 1, the exposure

may change into

in time interval,

. Here, exposure and vulnerability variables determine, together with hazard variable

, the value of the direct impact variable

. Nevertheless, an indirect impact may occur at time

, as a consequence of the impact

at time

. Lastly, the node

represents two possible regimes [

18] in which the model can work and the

vulneraR package can be used: with intervention and without intervention.

Different types of human intervention (manipulation) in the area can involve hard solutions such as building coastal structures, soft solutions, hybrid solutions, or even doing nothing (idle intervention). A causal arrow is therefore introduced in the DAG (

Figure 1), from the manipulation node

to exposure

and vulnerability

. Variable

is not associated with a PDF, but it always conditions

and

, but not

. This is the reason why a square vertex is plotted: it is set to “no intervention” by default and changed only if an actual manipulation-intervention is performed and the relative data are available. A detailed definition of exposure is provided in Pantusa et al. [

1] and in [

2], where the authors state:

Exposure includes the whole inventory of elements that can be adversely affected by an impact. Although reducing exposure to physical assets such as buildings and infrastructures is common practice, information associated with indirect effects (e.g., sectoral GPD, income) cannot be ignored. For instance, when an industrial plant becomes flooded, consequences are not limited to damages to structure and contents but can include loss of profits due to business interruption or delay.

thus variable

is also part of our context.

In accordance with our expert, we define the sample space of attributes and vulnerability variables across five distinct levels. Furthermore, the sample space for the exposure, hazard, and impact variables was specified using three levels.

Some further remarks are in order about the structure of our DAG (

Figure 1). Firstly, while in the original article by Pantusa et al. [

1] the distinction among geological, hydro-physical, and vegetation attributes is merely formal, as it does not affect the calculation of the final vulnerability index, in our model this distinction is reflected in their contributions to three separate vulnerability sub-indices:

,

, and

. In the proposed model, the three sub-indexes are later combined into one vulnerability index,

, that will indirectly contribute, through temporal evolution with

, to the evaluation of the direct impact

(next section for details). Secondly, an experienced reader might be surprised by the decomposition of the joint conditional PDF of the attributes given the vulnerability sub-index into conditional distributions of single attributes given the sub-vulnerability alone as follows:

but this “Naïve Bayes” configuration, despite being successful in many contexts, should be only considered a starting point before introducing more structure where appropriate, as in the Tree Augmented Naïve Bayes (TAN) by Friedman et al. [

19].

2.3. Elicitation

The sparse nature of our PGM facilitates human interpretation and makes elicitation less cognitively demanding. Elicitation is the process of representing expert knowledge and beliefs about uncertain quantities in a quantitative form by means of a (joint) probability distribution [

20,

21]. The person whose knowledge is elicited is called an “expert”. For this study, the expert selection criteria were a good understanding of geological, hydrological, and physical processes and an intimate knowledge of the case study area. The second key figure of an elicitation process is the facilitator, whose main task is to gather the expert’s knowledge—for example, by conducting the interview—and to carefully translate such knowledge into probabilistic form [

20].

A single expert elicitation is here considered by implementing an R package in order to reduce efforts and costs commonly associated with vulnerability assessments. Using elicited data, the goal is to define the conditional distributions of all vulnerability attributes and the marginal distributions of the vulnerability sub-indexes, the exposure at time , and hazard at time . The distributions of interest are as follows:

with a, v, e, and h the index for the class of the corresponding variable; index refers to the considered attribute, and to the type of vulnerability sub-index.

The decision to adopt either a direct or an indirect elicitation approach is determined by the nature of the quantities to be elicited. For the conditional probabilities of the attributes, , and for the distributions of , values were elicited indirectly. Indirect elicitation consists of using virtual transects, formulating questions such as: “Assume that you know for sure that you have 1000 transects belonging to context that have been given Geological Vulnerability score of 1 (very-low), then what is the lowest number of transects you believe would have a vulnerability score of 3 in the Geomorphology attribute? What would be the highest plausible number? What is the most plausible number of transects with a moderate vulnerability score (v.s. = 3) in Geomorphology?”. For and , a direct elicitation was performed by asking for probability estimates directly, without relying on virtual transects. For both the direct and indirect elicitation, the elicited answer is a triplet consisting of the minimum, median, and maximum values for an interval. A single triplet, for example, describes the degree of belief and the confidence of the expert about attribute taking score , given that the vulnerability sub-index (parent of attribute ) takes value , in other terms it gives information on .

A complete protocol for elicitation is provided within the vulneraR package, together with an Excel worksheet developed for the facilitator to collect the data. The protocol contains precise instructions, including scripts and descriptions that the facilitator can read aloud or provide to the expert. The worksheet explicitly includes written questions and spaces for recording the expert’s answers. These answers are then processed, converted into the format required by the package functions, and graphically elaborated to provide both the facilitator and the expert with immediate visual feedback on the progress of the interview, all within the same worksheet.

The literature supports the need for such a protocol (see [

21,

22,

23]). We found that a transparent record of the elicitation procedure, accompanied by step-by-step instructions, mitigates biases and misunderstandings while improving the interpretation and analysis of results. In the

vulneraR package, the function

get_elicita_files is provided to copy templates of the “.xlsx” file and of the elicitation protocol (“.pdf” file) in a selected folder.

The distributions for variables , , , , and are not elicited because they are defined through deterministic relationships among hyperparameters (see the next section). This choice reflects the expert’s degree of belief and also reduces the cognitive burden due to the large number of questions that would otherwise result.

2.4. The vulneraR Package

The

vulneraR package (link available in the

Supplementary Materials) is designed to analyze the data collected during an elicitation process, as described in the previous section, and to obtain PDFs for all the variables included in the model. Several functions have been implemented to support this task, guiding the user through the entire workflow: from data import to the definition of the PDFs, including the temporal evolution of some variables (nodes) in the model. The core functions of the package work at the hyperparameter level, so their outputs are vectors whose elements are lambda values, for example:

thus, for example, element

refers to the hyperparameter of the Dirichlet distribution when variable

takes value 1 given that the conditioning variable

is equal to 4.

The initial data expected by the package consist of a .csv file containing the Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs) of the attributes and one containing the triplets elicited for the vulnerability sub-indexes (, ), of the exposure node () and of the hazard node (). These files can be easily obtained if the elicitation was performed using the provided worksheet by exporting the dedicated self-filling sheets. These CPT sheets contain the elicited triplets and are read and loaded as dataframes by dedicated functions in the package.

The package follows a structured approach with respect to the model, finding each node’s distribution from left to right in the DAG. Attributes, sub-indexes, exposure, and hazard all have corresponding elicited data entering as arguments into the getLambdaAttr and getLambdaVEH functions. These functions work identically, but with different input dataframes. The reason for introducing two functions lies in the nature and structuring of the input data: while for the attributes the data are CPTs, in the case of the vulnerabilities, exposure, and hazard, there was not a conditioning variable, and therefore they are simple probability tables. Nevertheless, the functions follow the same implementation scheme and yield analogous results for the different elicited nodes.

Applying these two functions, the resulting 2 dataframes will contain the hyperparameters of the distributions of all the variables for which elicited data are available, which means the following:

- -

Geological attributes: ;

- -

Hydro-physical attributes: ;

- -

Vegetation attributes: ;

- -

Vulnerability sub-indexes: ;

- -

Exposure: ;

- -

Hazard: .

To exemplify these functions, a walk-through of the implementation and use of getLambdaVEH() will now be provided. The arguments of the function are as follows:

mydata—Dataframe containing the conditional probability tables for , , , and . It must have the same structure and format as the object returned by the loadDataVEH() function;

choice_quant—An array of three doubles specifying the quantiles to be associated with the (min, mean, max) triplet in the Beta fit of each variable class. The default is ;

manip—Matrix containing the probability shifts for each variable class. It must have the same structure and format as the object returned by the makeManip function. The default is the idle intervention represented by a identity matrix;

tr_number—One of two strings to define whether the values obtained through indirect elicitation were obtained setting a 1000 virtual transects scenario (“1000 tr”) or a 100 virtual transects scenario (“100 tr”). Defaults to “1000 tr”;

graph—Boolean variable, indicating whether the graphs should be produced (TRUE) or not (FALSE); the default is TRUE;

out_path—The folder where files are saved; if NA then the parent of the working directory is selected.

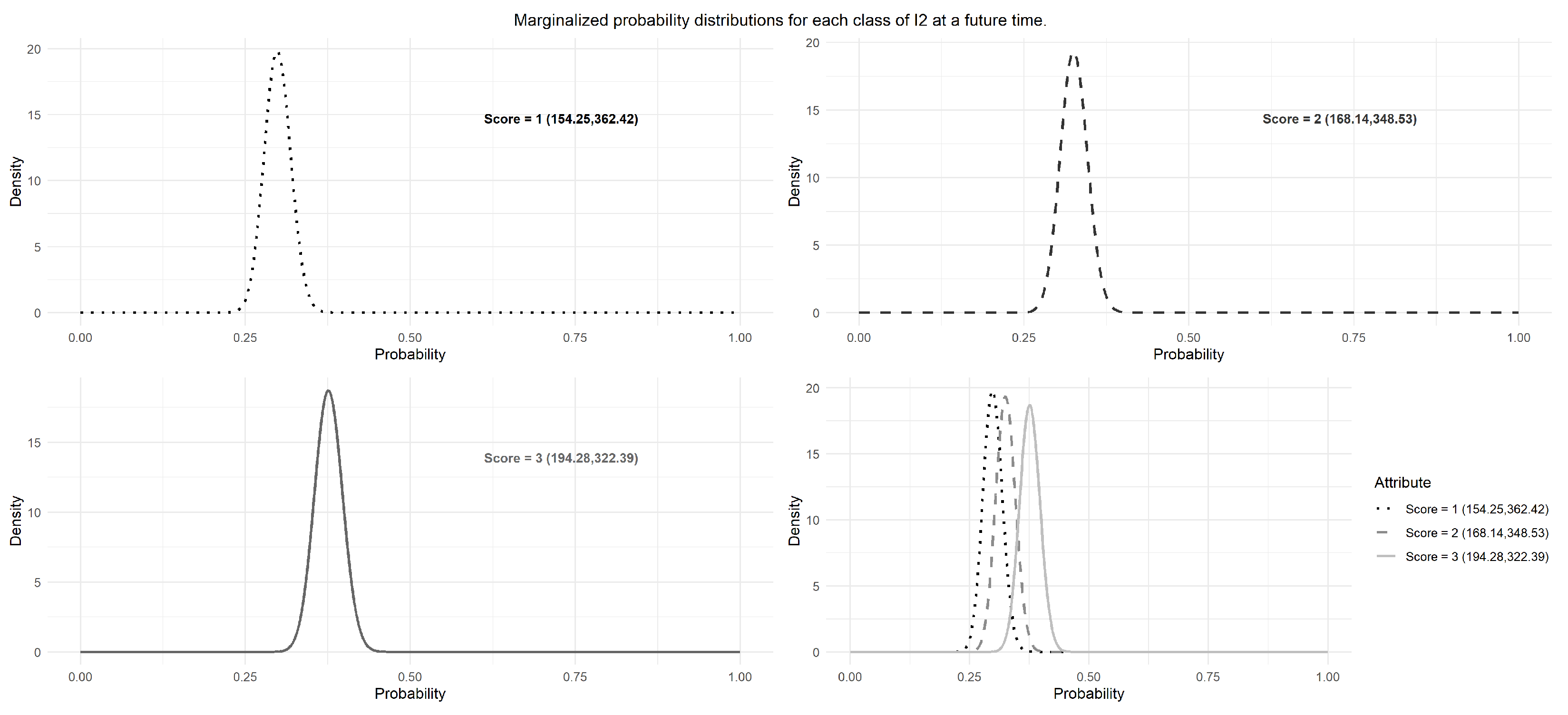

The function uses the provided dataframe and quantiles and initially relies on the SHELF package to perform an initial step where each class is fitted to a beta distribution such that the elicited triplet corresponds to the specified quantiles (argument) of the distribution. The five (or three, in the case of and ) beta distributions are then fitted to a five-dimensional (or three-dimensional) Dirichlet distribution. The beta and Dirichlet fits are performed using the fitdist and fitDirichlet functions of the SHELF package, respectively. As output, the function returns a dataframe containing the hyperparameters of the final fitted distribution (one row per variable, one column per class). If the graph argument is left to the default or set to TRUE, the function also produces plots of the marginal probability distributions of each class for the final Dirichlet distribution. These plots are saved in subfolders specified by the user or in the parent folder of the working directory. The files are organized hierarchically, according to whether an intervention was introduced or not.

The elicitation of the remaining nodes in the model is carried out through deterministic relationships at the hyperparameter level. Both

and

use linear combinations with similarly calculated weights, but in R they are implemented via different functions. Firstly, this choice was primarily due to two peculiarities of the nodes themselves. The linear combination is constructed to represent a perturbation of two terms (weights less than 1) around one dominant term (weight equal to 1). A separate implementation allows the dominant term for the total vulnerability

to vary depending on the context of application, meaning that the user can select which of the three sub-indexes will serve as the dominant one. In agreement with the results of the analysis performed by [

1] and with statements made by the expert during the elicitation, geological vulnerability was chosen as the most informative of the three sub-indexes for this study and is set as the default dominant term in the function implementation. The dominant term for

, on the other hand, is the total vulnerability, without the possibility of selecting another component as dominant. The second reason for a separate implementation involves the impact variable, because its parents have different dimension.

The hazard node has a sample space of size three; thus, , while variable , which is also of size three, has two parent nodes, thus a vector is required for each element in the Cartesian product made by the sample spaces of the parents nodes, variable and . As regards , the two lower classes and two higher classes were merged into a single class each to reduce the dimensionality of . Several points were considered while merging classes: (i) it is important to maintain the main features of the central class, because it is extremely informative, especially in the behavior of a variable; (ii) the two lower classes and the two higher classes show significant overlap in the distribution of ; and (iii) the merging procedure should carry an increase in uncertainty without introducing artifacts.

The selected transformations are:

therefore, the new three-dimensional vector of hyperparameters for

has the same lambda value in the central class as its five-dimensional counterpart and has a lower total sum, a feature that implies a wider dispersion in each class has, i.e., higher associated uncertainty.

A more in-depth description of the getLambdaV0 function follows, detailing its structure and weight selection. The arguments for the function are as follows:

lambdas—Dataframe containing all fitted hyperparameters for the vulnerability, exposure and hazard nodes. Must have the same structure and format as the object returned by the getLambdaVEH function.

first_term An integer number either 1, 2 or 3 to indicate which sub-index to use as a main component for the linear combination: 1 for V0geo, 2 for V0hp and 3 for V0veg. Defaults to 1, geological vulnerability as first component.

graph—Boolean variable, indicating whether the graphs should be produced (TRUE) or not (FALSE); the default is TRUE.

out_path—The folder where files are saved; if NA then the parent of the working directory is selected.

The function takes the output of the initial

getLambdaVEH function as argument: it contains the vector of hyperparameters for the three vulnerability sub-indexes required to calculate the scalar weights as in Equations (

11) and (

12). The choice of scalar weights calculated using the sum of all elements of the hyperparameter vectors of the sub-indexes ensures that all the classes of the variables’ distributions contribute equally. This implementation guarantees that changes brought on by the dominant term are greater as the perturbation term becomes more and more informative (larger

) with respect to the dominant class.

where

for the dominant term and analogously for the first perturbation term,

, and for the second one,

. The object returned is a dataframe containing the hyperparameters for the total vulnerability at time

,

. If the

first_term argument defaults (i.e., as per the Calabrian case study), the resulting hyperparameter vector is built as in Equation (

13)

where the dominant term is the geological one, the first perturbation term

is hydro-physical, giving

and the second one

is vegetation, giving

.

Lastly, the package includes a function to implement temporal evolution of a variable, tempEvol. This function takes as argument a vector of hyperparameters of a node and returns the vector of hyperparameters of the same node but at the subsequent time interval. The core principle that guides the deterministic relationship implemented for distributions at a future moment in time, is that temporal evolution does not change the expected value of a variable, but it does change the uncertainty associated with its distribution. So the child variable at would preserve the same expected value as that at time , but its distribution would be wider. This function also works at the hyperparameter level and increases the uncertainty of a temporally evolved distribution by increasing by 10% the distance between the 20% and 80% quantiles of the distribution in . The distribution the function acts on is the marginalized distribution of the central class of the variable of interest, selected as the most informative.

In an effort to reproduce its mitigating nature, intervention is implemented through a transfer of probability from a higher class of vulnerability (or exposure) to the adjacent lower class. Such implementation allows keeping control of the reaction of a single class to intervention, since even performing the same manipulation, “Moderate” vulnerability conditions might cause an area to respond very differently than “Very High” vulnerability conditions. Working within the intervention regime requires deep knowledge of both the technique in use and the area of interest. Indeed, this critical step is better solved if an extensive study of the selected context, here the Calabrian coast, is performed, taking into consideration the type of intervention, its expected performance, and the site response in order to properly quantify the probability shifts required by the package.

Within the package, the possibility to work under different regimes, intervention or no intervention, is selected by the user when invoking the getLambdaVEH function. The function itself calls for the manipulation matrix as an argument. If the regime is that of no intervention, then no action is required and manipulation defaults to the identity matrix to implement an idle regime. The non-identity matrix required by an intervention regime may be produced using the makeManip function. The function calls for the following arguments:

probshift_Vgeo—Probability shifts for Geological vulnerability: 5-element numerical array containing 5 values between 0 and 1; default is rep(0,5).

probshift_Vhp—Probability shifts for Hydro-physical vulnerability: 5-element numerical array containing 5 values between 0 and 1; default is rep(0,5).

probshift_Vveg—Probability shifts for Vegetation vulnerability: 5-element numerical array containing 5 values between 0 and 1; default is rep(0,5).

probshift_E—Probability shifts for Exposure: 5-element numerical array containing 5 values between 0 and 1, the first 3 regarding the exposure classes and the last two as fillers; default is rep(0,5).

A numerical example helps sharpen intuition. If the expected effect of the intervention is to shift of probability from class 4 to class 3 of the geological vulnerability, the 4th element of the geological argument should be . The first element of each vector should be 0 since there is no lower adjacent class, and other values will be ignored.

The probability shift is performed at the hyperparameter level by the

getLambdaVEH function. It checks whether the matrix argument is the identity matrix and behaves accordingly. Intervention shifts the expected value

for a parameter

of the

vulnerability class (

), but does not change the associated uncertainty (

). In the case of a hypothetical intervention that requires the transfer of

of probability from Class 5 to Class 4 and then another

transfer from Class 4 to Class 3, then the expected value of Class 4 after intervention,

, is calculated as in Equation (

14) as follows:

where the hyperparameter for Class 4 after manipulation is

.

We conclude this section by emphasizing that providing an explicit definition of probability shifts for each affected variable is essential. Such a definition enables a rigorous characterization of the intervention regime, through a user-defined manipulation matrix.