Abstract

In this paper, we prove that the Taylor expansions of analytic functions appearing in the linearization of quadratic maps at hyperbolic fixed points do not successfully approximate invariant manifolds, such as stable and unstable manifolds, when higher-order terms are truncated. This fact was pointed out by Newhouse et al. in their numerical experiments, and implies that the Taylor expansions are inadequate for quantitatively studying dynamical systems such as quadratic maps. In fact, it is shown that the computational complexity for the approximations by the Taylor expansions grows exponentially.

Keywords:

discrete dynamical systems; Hénon maps; linearization; Taylor expansions; hyperbolic fixed points; computational complexity MSC:

37D45; 37M21; 68Q17; 39A13; 41A10

1. Introduction

The Hénon map is a quadratic map defined by

where are parameters, and ([1]). Let be one of the fixed points of f, and let be the eigenvalues of the derivative . Throughout this paper, we assume

and set . Then

holds, where . Two cases occur: and . We recall that P is hyperbolic when in addition. If or , then P is a saddle. This paper treats the case satisfying the following condition:

which is more general than the saddle case.

The following result on the linearization of dynamical systems is well-known (cf. [2]).

Proposition 1.

(Poincaré [3]) Under the above assumptions, for any eigenvector for α, there uniquely exists a holomorphic map satisfying and such that

for all . Furthermore, is injective and for all , .

The map in Proposition 1 is called Poincaré’s map. The image

is the invariant manifold associated with , which coincides with the stable or unstable manifold when P is a saddle. By Proposition 1, is actually f-invariant (i.e., ) and an injective immersed submanifold of through P. We equip the intrinsic metric on induced by .

Franceschini and Russo [4] used Poincaré’s map for numerical calculations to detect homoclinic points in the case where a and b are the original Hénon’s parameter values. Also, Fornaess and Gavosto [5,6] investigated the existence of homoclinic tangencies using Poincaré’s map. The existence of higher-dimensional Poincaré’s maps was investigated by Cabré, Fontich, and de la Llave [7,8,9]. Anastassiou, Bountis, and Bäcker [10] used their result to detect homoclinic points for the 4-dimensional maps. Also, Newhouse, Berz, Grote and Makino [11] estimated the topological entropy of the Hénon map using symbolic dynamics via the Taylor models in addition to Poincaré’s map. We emphasize that Poincaré’s maps were expressed in Taylor expansions in those studies.

It is important to clarify how the Taylor expansions work for quantitative studies of dynamical systems, such as numerically calculating the topological entropy or detecting the homoclinic set (cf. [11,12,13]). In this paper, we prove that the computational complexity for the approximations by the Taylor expansions grows exponentially, which is precisely stated as follows.

Theorem 1.

When (resp. ), if the disk centered at P with radius (resp. ) in the invariant manifold with respect to the intrinsic metric is computationally realized with high computational accuracy in by the map , then the order of the truncation terms in the Taylor expansions of must be greater than N satisfying the condition

where L is a natural number given arbitrarily.

This result implies that the Taylor expansions are inadequate for quantitative studies such as numerically calculating the topological entropy or detecting the homoclinic set, which was pointed out by Newhouse, Berz, Grote, and Makino [11] in their numerical experiments.

2. Main Results

To state the main results of the current paper, we mention the construction of Poincaré’s map . For simplicity, let us consider a conjugate map of the above map by the translation on sending P to the origin , i.e.,

Set

Then, from the relation (1), we have

and . Setting a series expansion

and substituting this into the above relation (3), we obtain by the coefficient comparison

where . Note that the non-resonance condition that for all is assumed here. This condition is automatically satisfied when P is a saddle. The first-order coefficient is determined by the condition , and .

Choosing as a branch of , we introduce a new variable by the transformation

and define . Let . We define a holomorphic map by . Then, from the relation (1), it follows that by the l-th iteration () of f, any point in the invariant manifold is mapped as follows:

For each , let

Then from (4), we have

We discuss the convergence of the series (7), assuming that are given arbitrarily.

2.1. Rapid Deterioration of Convergence in Taylor Expansions

Write and in the form of real and imaginary parts. For simplicity, we set

and let

Define a natural number as

where denotes the Gauss’s symbol. We notice that grows exponentially with respect to , if is chosen to be negative when , and to be positive when , respectively.

The purpose of this paper is to give a lower bound to the magnitude of each higher-order term of the series (7) as follows.

Theorem 2.

There exists a constant such that if and () are satisfied, and if is close to zero, then there is ϵ with such that

The above result gives a mathematical description of the fact that the approximation of described by the Taylor expansion (4) or (7) rapidly deteriorates as the value becomes large when higher-order terms are truncated.

To state how the series (4) converges, let us denote by the remainder term:

where N is a natural number. The following estimate holds.

Theorem 3.

Let . Then there exists a constant such that for every , if a natural number N with is large enough, the remainder term is estimated as

for any s with , where is the constant stated in Theorem 2. When , a similar statement holds if α is replaced with .

Theorem 1 is obtained from Theorem 3 as follows.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let for . If the higher-order terms in the series (4) are truncated after N-th, the error E for the point is estimated as

by (11). If the right-hand side of this estimate is small enough, we need the condition that

which is equivalent to . Thus, we obtain the necessary condition (2). In the same way as above, we obtain the conclusion for the case of . The proof of Theorem 1 is complete. □

2.2. Discussion: Beyond Taylor Series

The following examples 1 and 2 specifically illustrate how pessimistic the implications of Theorems 2 and 3 are.

Example 1.

Example 2.

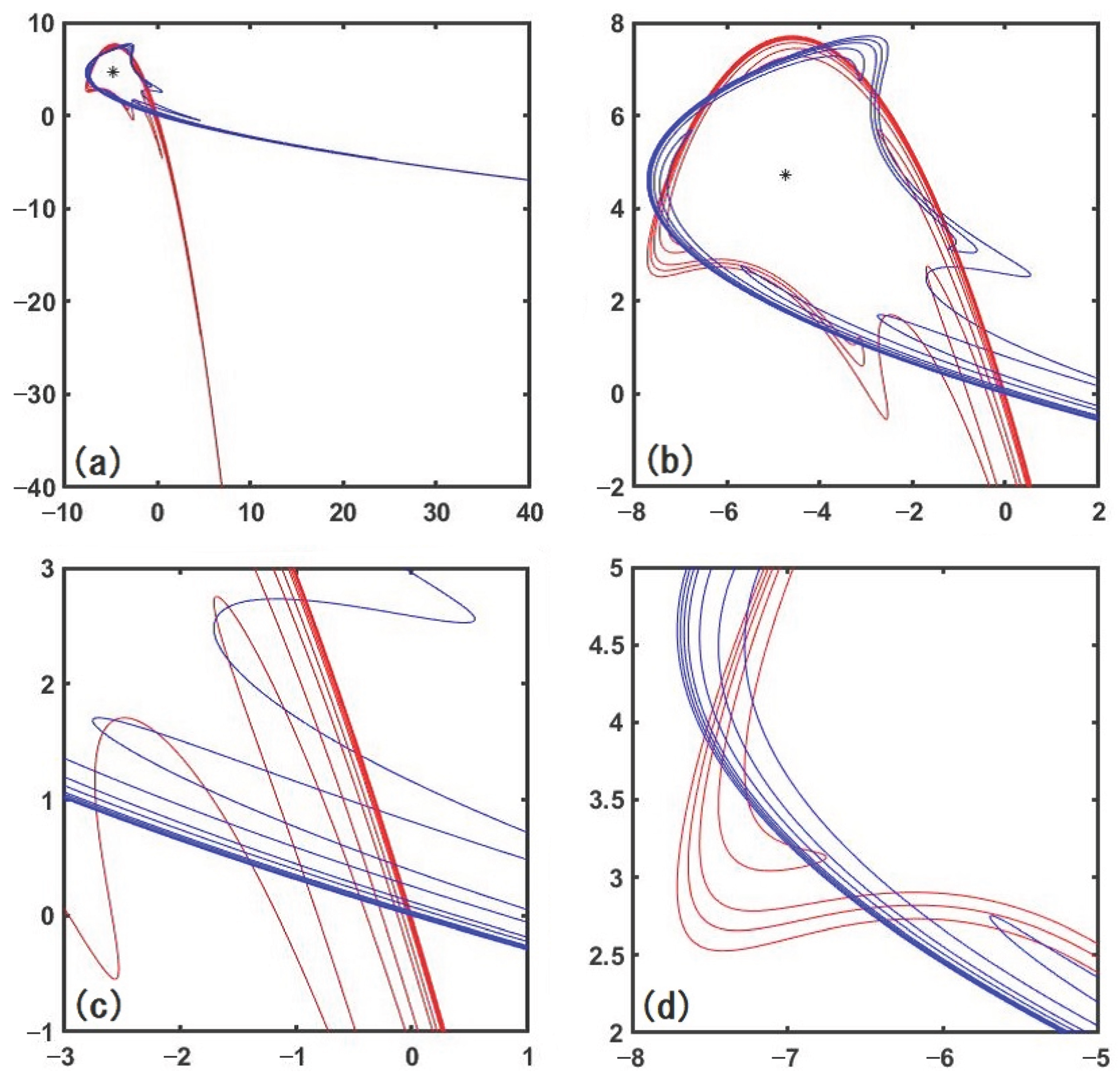

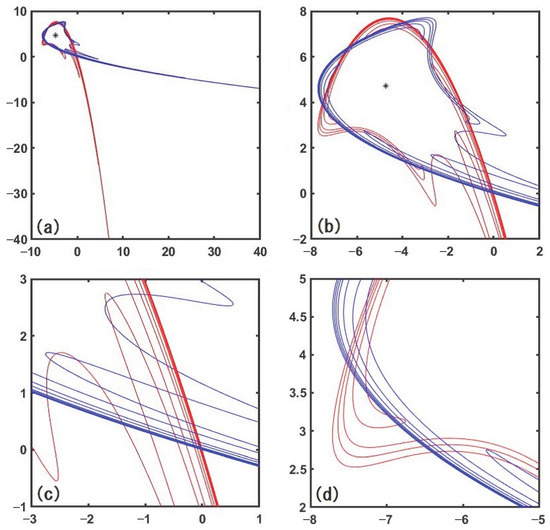

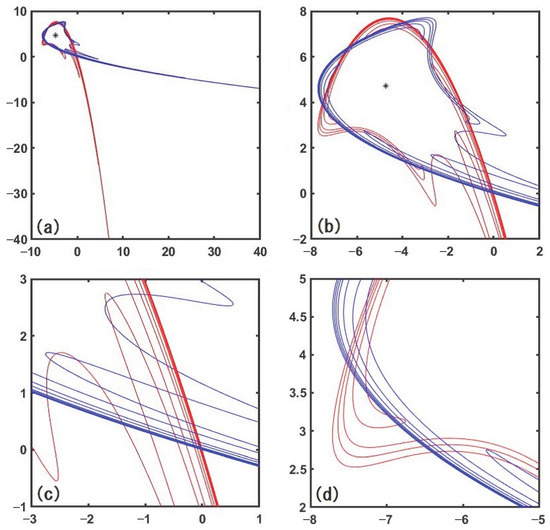

Here, we present an example of stable and unstable manifolds depicted by using the Taylor expansion (7). Figure 1 shows a chaotic system encircling KAM tori in a symplectic case. We select the eigenvalues α as for the stable manifold and for the unstable manifold, respectively. Then, the dynamical parameter satisfies . Also λ and a in (3) are given as and , respectively. For these parameters, one fixed point is elliptic () and the other is a saddle point. The eigenvalues and at the saddle point [ here] are (stable) and (unstable). For , the branch is chosen as and the variable t is selected to be real numbers with ranges and by setting and , respectively. When , (8) gives . We similarly choose the branch and the variable t for . In this numerical computation, we take the number of truncation N in the series (7) as . Concentric KAM tori (and periodic orbits) exist inside the chaotic system. The number in Theorem 2 in this example is for .

Figure 1.

A chaotic system encircling KAM tori, where and . The asterisk denotes an elliptic fixed point. Panel (b) is the enlarged figure of (a), and panels (c,d) are further enlarged views of (b). The red and blue curves denote the stable and unstable manifolds, respectively.

To improve the pessimistic situation as stated above, Newhouse, Berz, Grote, and Makino [11] introduced the notion of the Taylor models by restricting the parameter s such that the set ( or ( is contained in a given bounded set, in which they rigorously estimated the topological entropy of Hénon maps using symbolic dynamics. See also Ishii [12].

In correspondence to such a development, it has been obtained very recently by the authors that the holomorphic maps defined by taking conjugates by iteration maps of the Hénon map and of the derivative give much better approximations of theoretically and numerically when the parameter s is restricted as above, where is the polynomial map with degree N when higher-order terms are truncated from .

It is well-known that the method of contraction mappings is useful in studying invariant manifolds and dynamical stability (cf. [14]). Such a method might also work for the approximation of theoretically and numerically.

The invariant manifold can be described by a divergent series called asymptotic expansion in Poincaré’s sense, and a phenomenon similar to the Stokes phenomenon and to differential equation theory occurs. For details, we can refer to Tovbis [15], Lazutkin, Schachmannski and Tabanov [16], Gelfreich and Sauzin [17], Lazutkin, Segur and Hakim [16,18,19], Écalle [20,21,22], Sternin and Shatalov [23], Voros [24], and Matsuoka and Hiraide [13,25,26,27]. The results of those studies have made it possible to quantitatively investigate the dynamical system of the Hénon map f with extremely high precision using computers, which suggests that the asymptotic expansion gives us much better performance than the ones stated in Theorems 2 and 3. The authors hope that the research area will be developed in discrete dynamical systems.

3. Proofs of Theorems 2 and 3

To prove Theorems 2 and 3, we prepare the following Lemmas 1 and 2, which gives sharp estimates on upper and lower bounds to absolute values of the coefficients () (cf. [5,6]). In the following, suppose that .

Lemma 1.

There exists a constant such that

holds for all , where .

Lemma 2.

There exists a natural number such that

holds for all .

The above results are stronger than the estimate obtained by Fornaess and Gavosto [5,6] via complex analysis.

Lemmas 1 and 2 also hold for , if is replaced with . The proofs of Lemmas 1 and 2 are provided in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively.

Define a real function

Then, we have

which is equivalent to the relation (8) because the case of is considered. It follows that takes its minimum value at for a fixed t.

Let

where is the constant stated in Lemma 1, and define a real function

By using Lemmas 1 and 2, the following Lemma 3 is easily checked.

Lemma 3.

If is the number as in Lemma 2,

holds for any .

Proof of Theorem 2.

Let be the number as in Lemma 2. Since

by Lemma 3 we obtain

Taking into account, we have

Proof of Theorem 3.

Let us express as

where

Let . Then, from Lemma 3 we can estimate as

Let be given arbitrarily. Choosing to be sufficiently large, we have that if

is satisfied, then

holds for any . Then, from (16) it follows that

Since

the conclusion is obtained from Lemmas 1 and 2. In the same way as above, we obtain the conclusion for the case of . The proof of Theorem 3 is complete. □

4. Proof of Lemma 1

In this section, we give the proof of Lemma 1

Since , by the definition, there exists a constant such that

holds for all , and then we can choose such that

is satisfied for any . Take a constant such that the inequality (12) holds for . Let , and assume that and satisfy the inequality (12).

Then we have

Noticing , we have the result that the exponent part of in the above inequality takes the minimum value at . Therefore,

Using the expansion

we obtain by (18) and (19) that

which implies that the inequality (12) holds for . Therefore, the conclusion is obtained. The proof of Lemma 1 is complete.

In the same way as above, we obtain Lemma 1 for .

5. Lower Bounds to Absolute Values of Coefficients ’s

We give in this section the proof of Lemma 2. We first introduce a function for measuring the growth of an entire function at infinity (cf. [28]). Let be an entire function and define a function on by

The growth of g is defined by

If g is expressed in the form of the power series , the growth is characterized by

For more details on the growth , refer to [28], pp. 4, Theorem 2; [29], pp. 257, Theorem 9.4.

5.1. Growth of at Infinity

To prove Lemma 2, we prepare the following Lemma 4 that is already known ([30]). For completeness, a simple proof is given.

Lemma 4.

Let . Then

holds. When , a similar statement holds if α is replaced with .

Proof.

For , we denote by the open disk with radius r centered at the origin in ℂ. Then there exists a maximum value

Note that is not a constant. Fix to be sufficiently large. Then is large enough. By the maximum modulus theorem, is attained at some point in the boundary of , i.e., . Since , we have , and so . Since is large enough, it follows that

Letting , we have . Then

holds. Let , and assume that

Then we have

Therefore, the inequality (21) holds for all .

For any point s in the closure of we have

and hence,

Repeating this procedure, we obtain the estimate

for any and s in the closure of , where . From the inequality (23), we have

where is a constant. This yields

5.2. Proof of Lemma 2

In the following, suppose that . Let be the sequence provided in (5). By Lemma 4, for each sufficiently small positive number , there exists a natural number large enough such that

We note that the estimate (25) holds for a sequence of natural numbers, and goes to infinity as . To show Lemma 2, the lower bounds in (25) are used.

Proof of Lemma 2.

Let . For given, we define a sequence by the recurrence relation

Set

Here, we remark that the exponents of are artificial factors to accelerate the divergence.

Using the relation (27), we have

for any n with . Therefore, if we set

then

holds for every n with , and we especially have

To prove Lemma 2, we discuss the divergence properties of the sequence from both upper and lower in the following.

Choose such that

for all . It should be noted that is given arbitrarily and the sequence is defined as above. We choose N as . Then there exists a constant such that

is satisfied for any n with .

Now, we show that the right-hand side of (33) gives an upper bound of for every n with . Let and assume that satisfy the inequality (33). Since the minimum value of the function

occurs at and is monotonically increasing in the interval , using the relation (27), we have

by which we have the inequality (33) for . Therefore, the inequality (33) holds for any n with .

Let be sufficiently small. From the lower bound of the estimate (25), by choosing to be large enough if necessary, it follows that

To show the estimate (13), we set and let as in (30). Let . Since

by the relations (32) and (27), we have

Noticing that , the right-hand side of the above inequality is less than

Since , taking sufficiently large if necessary, we can choose a constant with such that

Therefore, the inequality (35) holds for .

Since

by the relations (29), (31), and (27), from the above result, we obtain the inequality (34) for . Next, set and let . Then, in the same way as above, we obtain the inequality (34) for . Repeat this procedure. We obtain

for any n satisfying . Since goes to infinity as , the estimate (13) is obtained for any . The proof of Lemma 2 is complete. □

In the same way as above, we obtain Lemma 2 for .

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we have clarified that the Taylor expansions of analytic functions appearing in the linearization of Hénon maps at hyperbolic fixed points do not successfully approximate invariant manifolds, such as stable and unstable manifolds, when higher-order terms are truncated, by proving that the computational complexity for the approximations by the Taylor expansions grows exponentially. The key findings are to obtain the upper and lower bounds to the absolute values of the coefficients in the Taylor expansions.

One of the future works is to clarify that the holomorphic maps defined by taking conjugates by iteration maps of the Hénon map and of the derivative give much better approximations of invariant manifolds than the Taylor expansions under some assumptions. The other is to show that the asymptotic expansion gives us much better performance as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; Methodology, K.H.; Software, C.M.; Validation, C.M.; Formal analysis, K.H. and C.M.; Investigation, K.H. and C.M.; Resources, C.M.; Writing—original draft, K.H. and C.M.; Visualization, C.M.; Supervision, K.H.; Project administration, K.H. and C.M.; Funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (Grant No. 17K05371, Grant No. 18K03418, Grant No. 21K03408, and Grant No. 25K07155) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the joint research project of ILE, Osaka University, Osaka Central Advanced Mathematical Institute (OCAMI), Osaka Metropolitan University, and the Research Institute for Mathematical Sciences, an International Joint Usage/Research Center located in Kyoto University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments that helped to improve the quality of this article. We sincerely appreciate the time and effort invested in the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hénon, M. A two-dimensional mapping with a strange attractor. Commun. Math. Phys. 1976, 50, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosawa, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Ueda, T. Holomorphic Dynamics; Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 66; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Poincaré, H. Sur une classe nouvelle de transcendantes uniformes. J. Math. 1890, 6, 313–365. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini, V.; Russo, L. Stable and unstable manifolds of the Hénon mapping. J. Stat. Phys. 1981, 25, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaess, J.E.; Gavosto, E.A. Existence of generic homoclinic tangencies for Hénon mappings. J. Geom. Anal. 1992, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaess, J.E.; Gavosto, E.A. Tangencies for real and complex Hénon maps: An analytic method. Exp. Math. 1999, 8, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, X.; Fontich, E.; de la Llave, R. The parameterization method for invariant manifolds I. Manifolds associated to non-resonant subspaces. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 2003, 52, 283–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, X.; Fontich, E.; de la Llave, R. The parameterization method for invariant manifolds II. Regularity with respect to parameters. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 2003, 52, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, X.; Fontich, E.; de la Llave, R. The parameterization method for invariant manifolds III. Overview and applications. J. Diff. Eqs. 2005, 218, 444–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiou, S.; Bountis, T.; Bäcker, A. Homoclinic points of 2D and 4D maps via the parametrization method. Nonlinearity 2017, 30, 3799–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, S.; Berz, M.; Grote, J.; Makino, K. On the estimation of topological entropy on surfaces. Geometric and probabilistic structures in dynamics. Contemp. Math. 2008, 469, 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Y. Dynamics of polynomial diffeomorphisms of ℂ2: Combinatorial and topological aspects. Arnold Math J. 2017, 3, 119–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, C.; Hiraide, K. Detecting homoclinic points in nonlinear discrete dynamical systems via resurgent analysis. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhenniche, A.; Chertovskih, R.; Gonçalves, R. Convergence analysis of reinforcement learning algorithms using generalized weak contraction mappings. Symmetry 2025, 17, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovbis, A. Asymptotics beyond all orders and analytic properties of inverse Laplace transforms of solutions. Commun. Math. Phys. 1994, 163, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazutkin, V.F.; Schachmannski, I.G.; Tabanov, M.B. Splitting of separatrices for standard and semistandard mappings. Phys. D 1989, 40, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfreich, V.; Sauzin, D. Borel summation and splitting of separatrices for the Hénon map. Ann. Inst. Fourier 2001, 51, 513–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkim, V.; Mallick, K. Exponentially small splitting of separatrices, matching in the complex plane and Borel summation. Nonlinearity 1993, 6, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segur, H.; Tanveer, S.; Levine, H. Asymptotics Beyond All Orders; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Écalle, J. Les Fonctions Résurgence; Publications Mathématique d’Orsay: Paris, France, 1981; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Écalle, J. Les Fonctions Résurgence; Publications Mathématique d’Orsay: Paris, France, 1981; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Écalle, J. Les Fonctions Résurgence; Publications Mathématique d’Orsay: Paris, France, 1985; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sternin, B.Y.; Shatalov, V.E. Borel–Laplace Transform and Asymptotic Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Voros, A. The return of quartic oscillator: The complex WKB method. Ann. Inst. H. Poincaré 1983, 39, 211–338. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, C.; Hiraide, K. Special functions created by Borel–Laplace transform of Hénon map. Electron. Res. Ann. Math. Sci. 2011, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, C.; Hiraide, K. Entropy estimation of the Hénon attractor. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2012, 45, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, C.; Hiraide, K. Computation of entropy and Lyapunov exponent by a shift transform. Chaos 2015, 25, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.J. Distribution of Zeros of Entire f Functions; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Markushevich, A.I. Theory of Functions of a Complex Variables; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffis, NJ, USA, 1965; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, K. On solutions of the Poincaré equation. Proc. Japan Acad. Ser. A Math. Sci. 1991, 67, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).