Simulation Teaching of Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Aiming at addressing the problem whereby the leader reference signal cannot be directly obtained due to time-varying faults in the communication link, a new distributed adaptive estimator is designed to reconstruct the required convex hull signal online, laying a foundation for the realization of containment control.

- A nonlinear filter with a dynamic compensation term is introduced. Compared with traditional linear filters, it can more effectively handle the differential explosion problem and suppress the filtering error in backstepping design, and enhance the system’s resilience and transient performance.

- A unified adaptive framework is proposed, which can simultaneously estimate the multiplicative fault- and additive fault-related values of the actuator online and generate an active compensation signal, effectively eliminating the negative impact of hybrid faults on the system performance.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

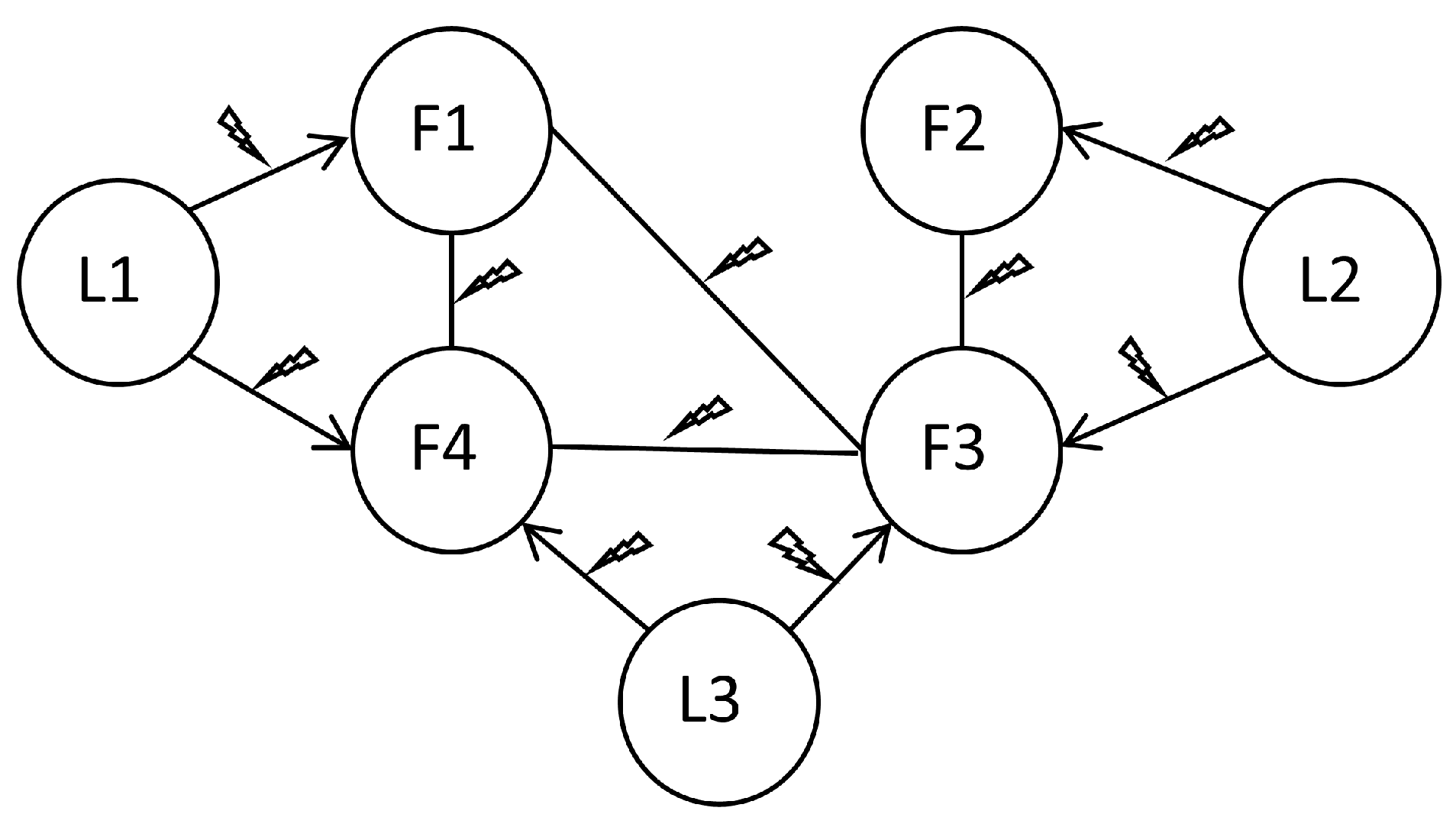

2.1. Graph Theory

2.2. Communication Link Faults

2.3. Problem Formulation

2.4. Control Objective

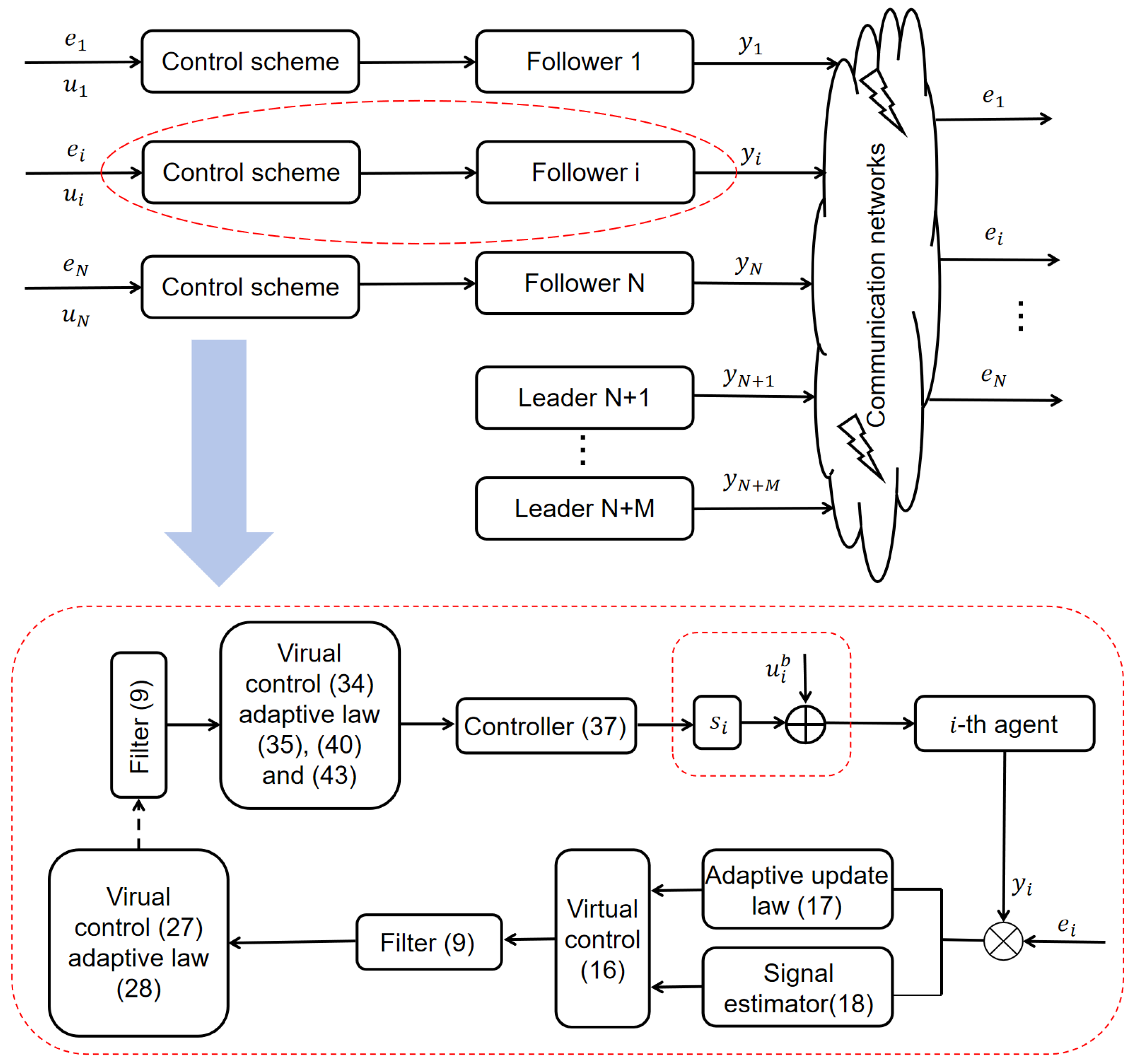

3. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Controller Design

3.1. Recursive Design

3.2. Fault-Tolerant Controller Design

3.3. Stability Analysis

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

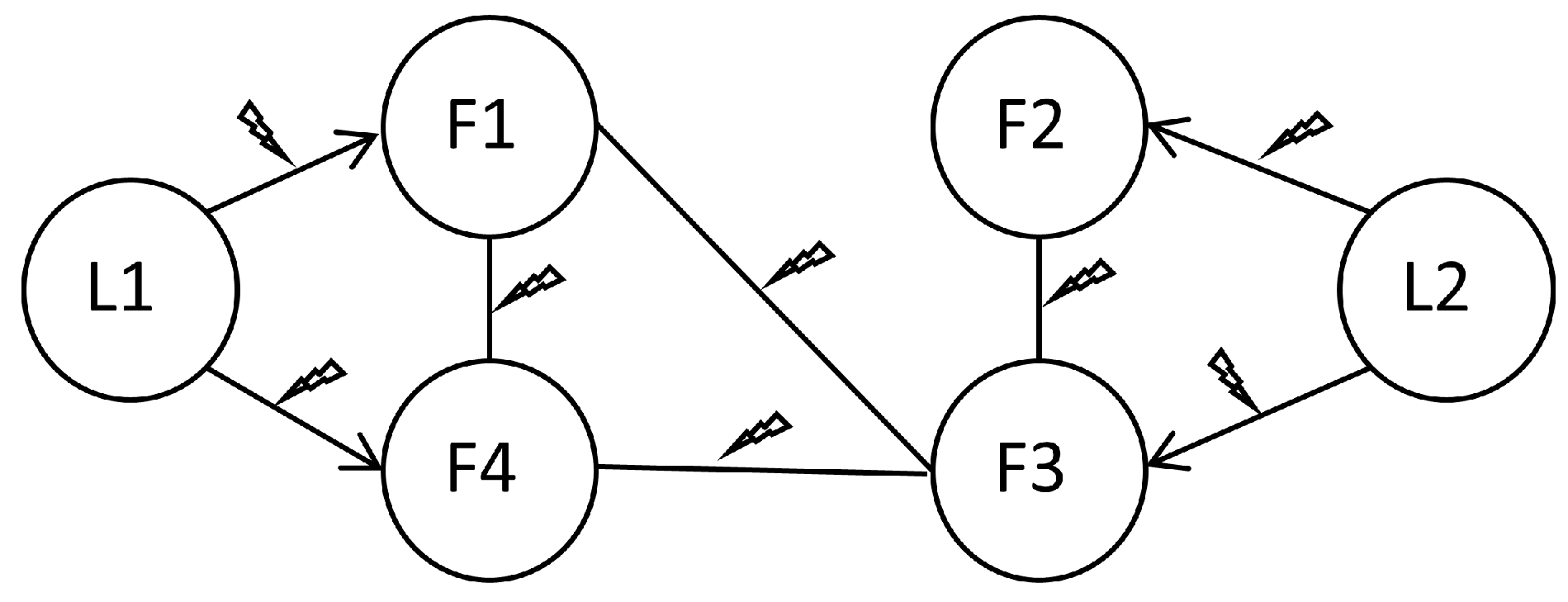

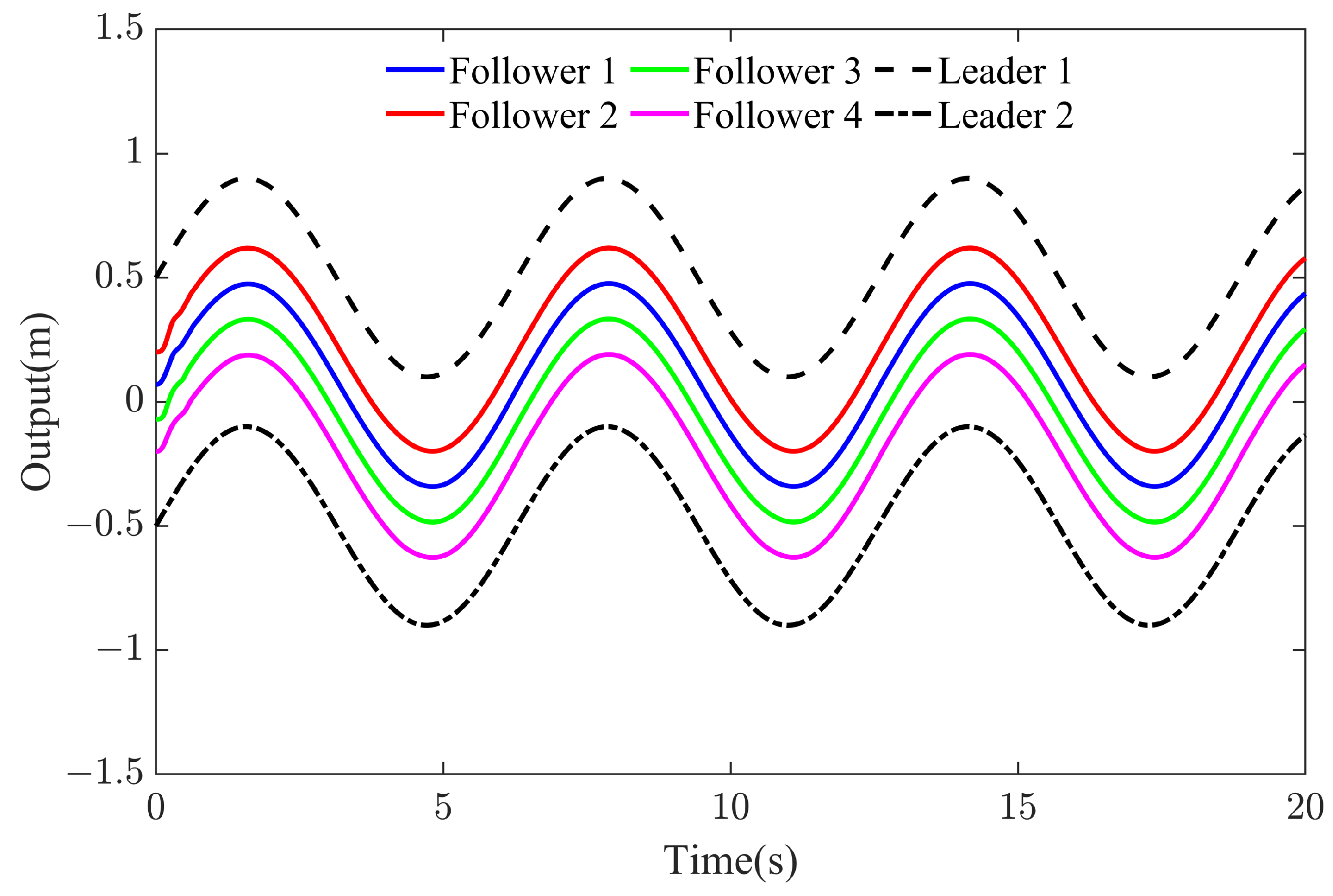

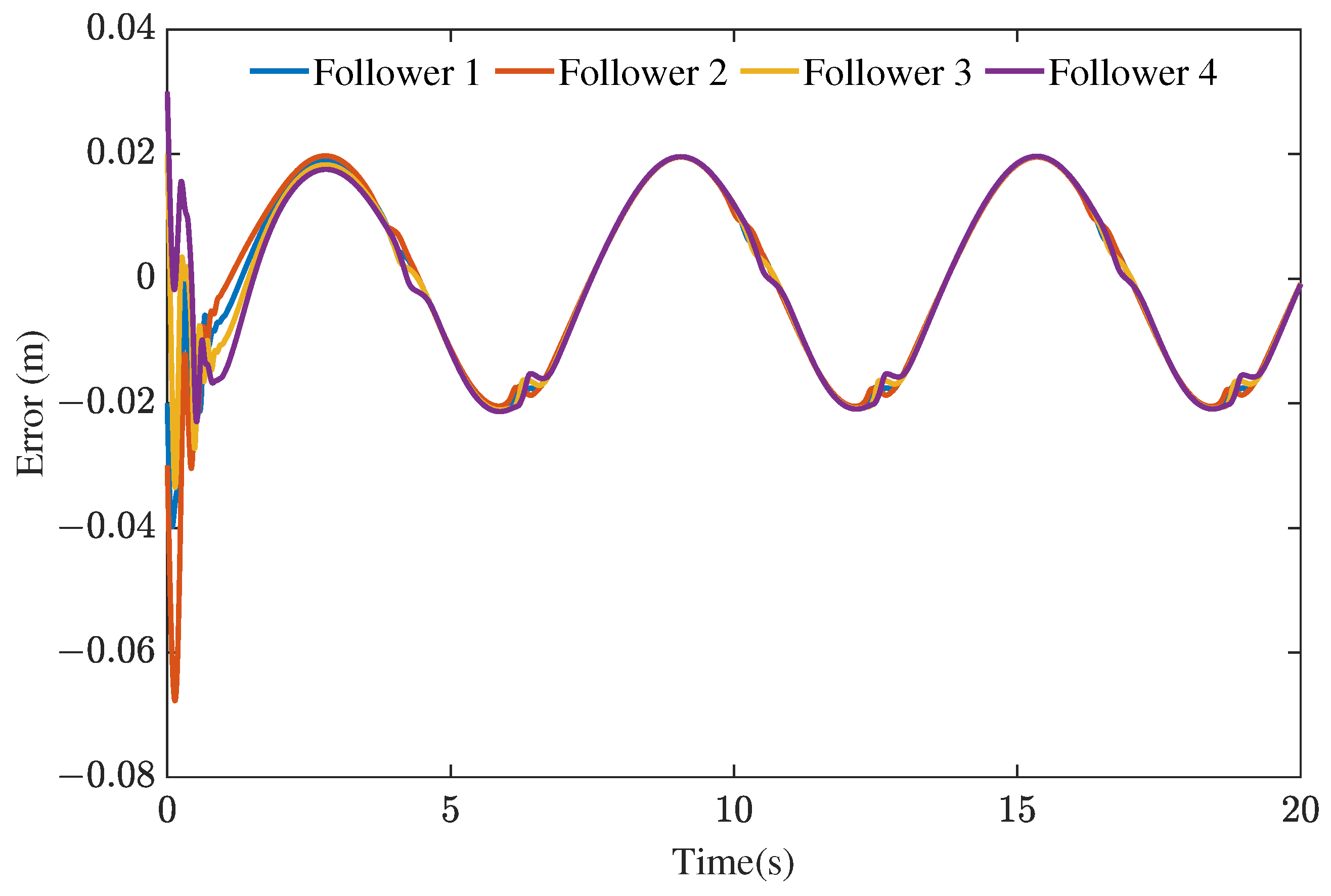

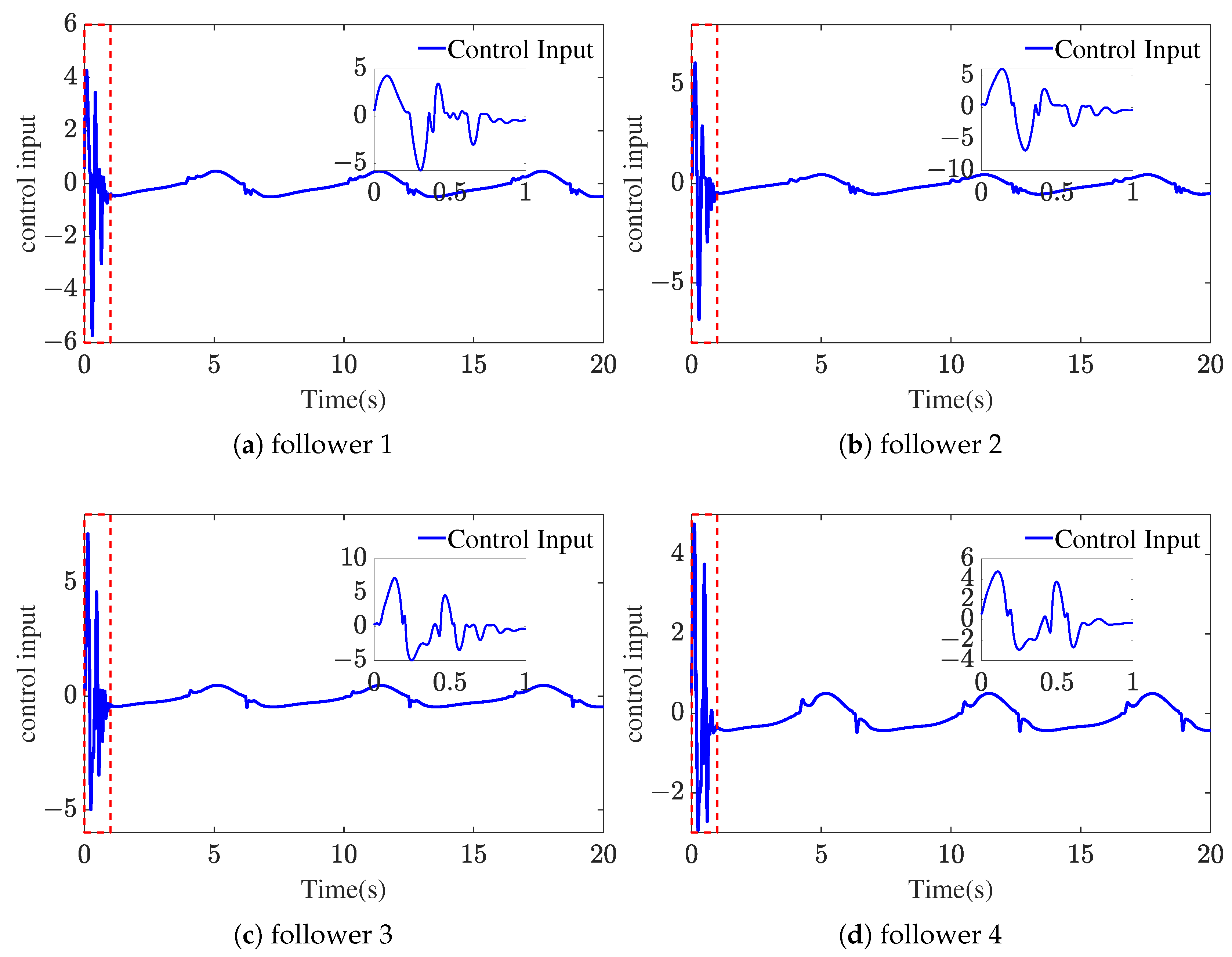

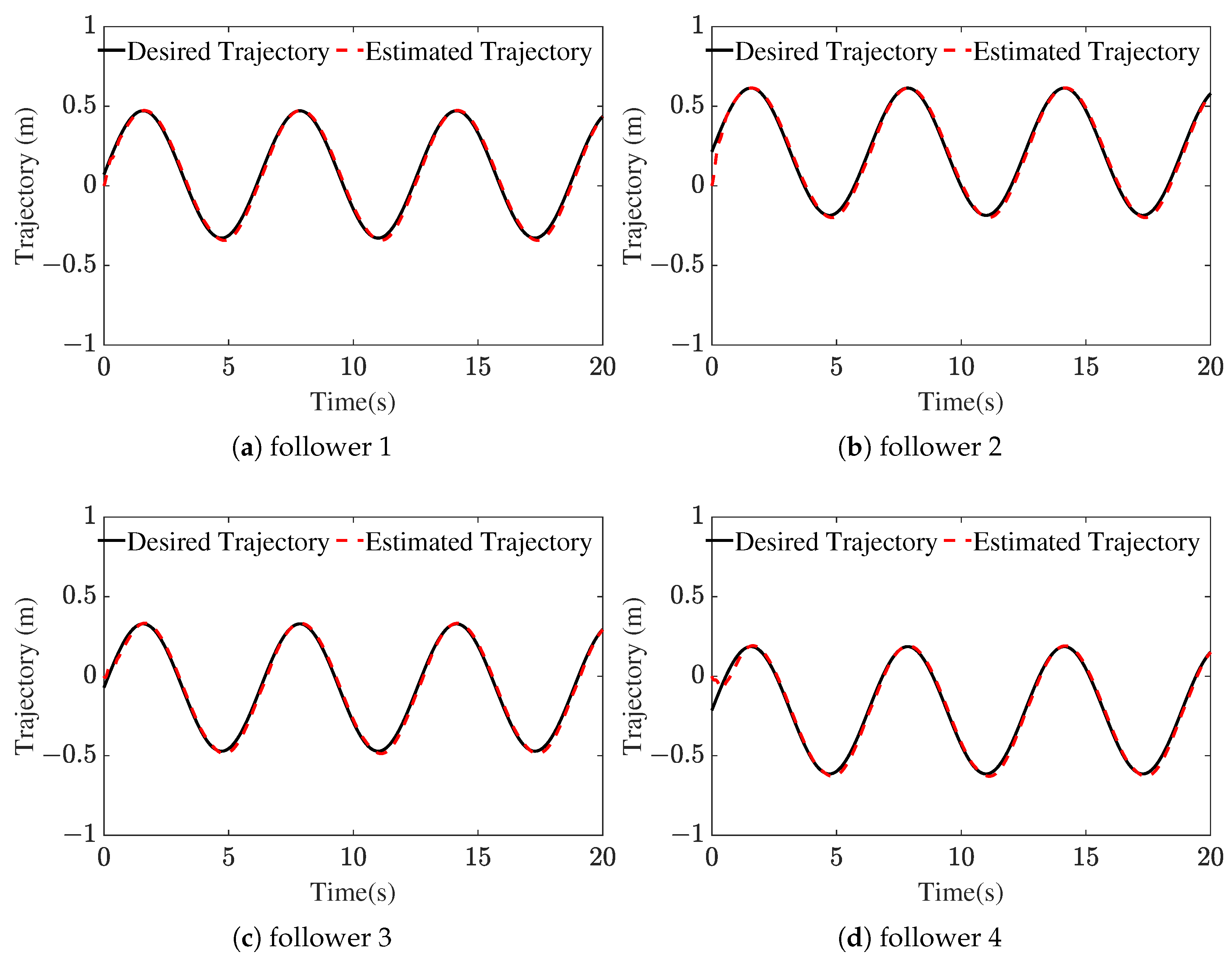

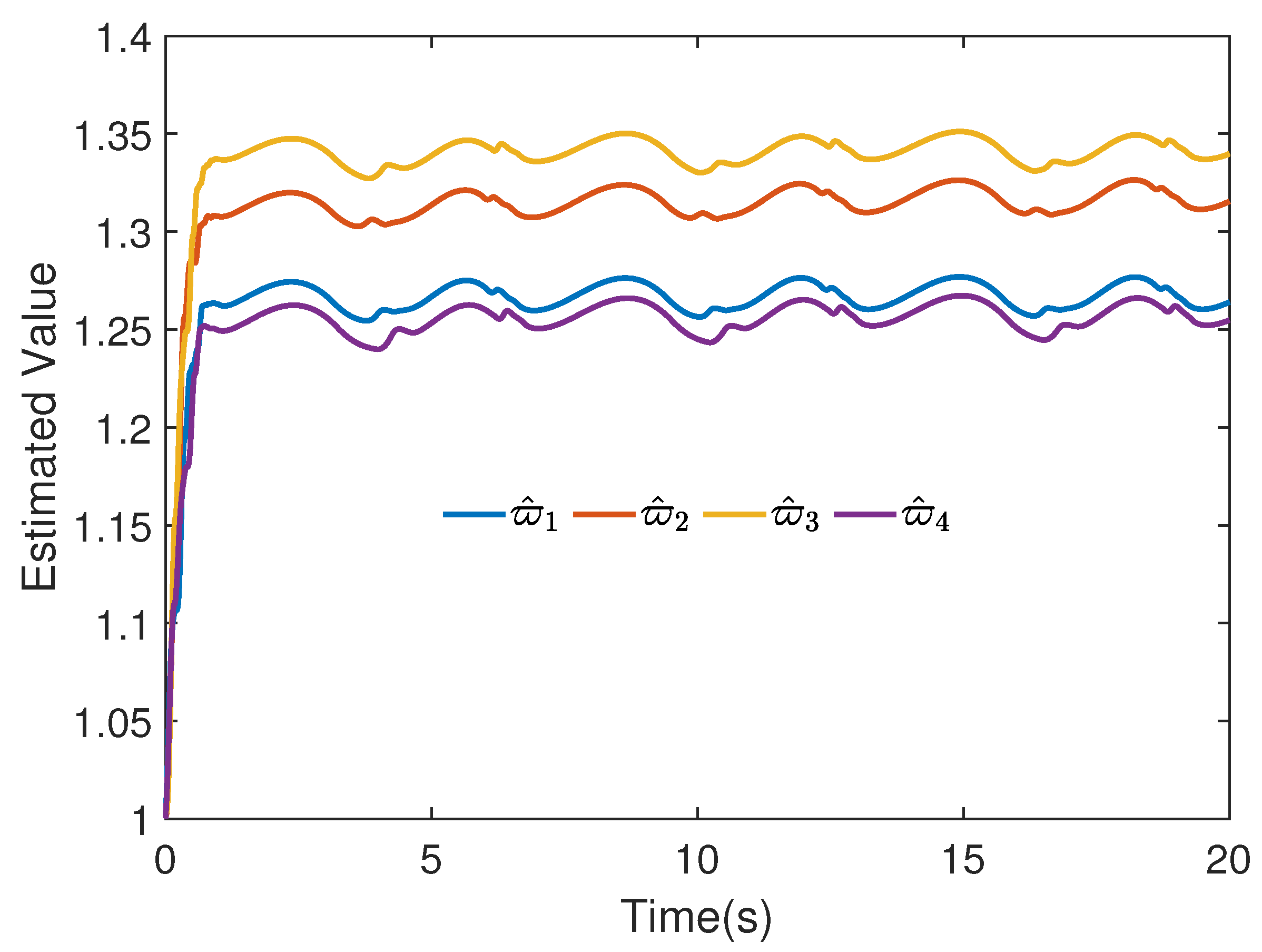

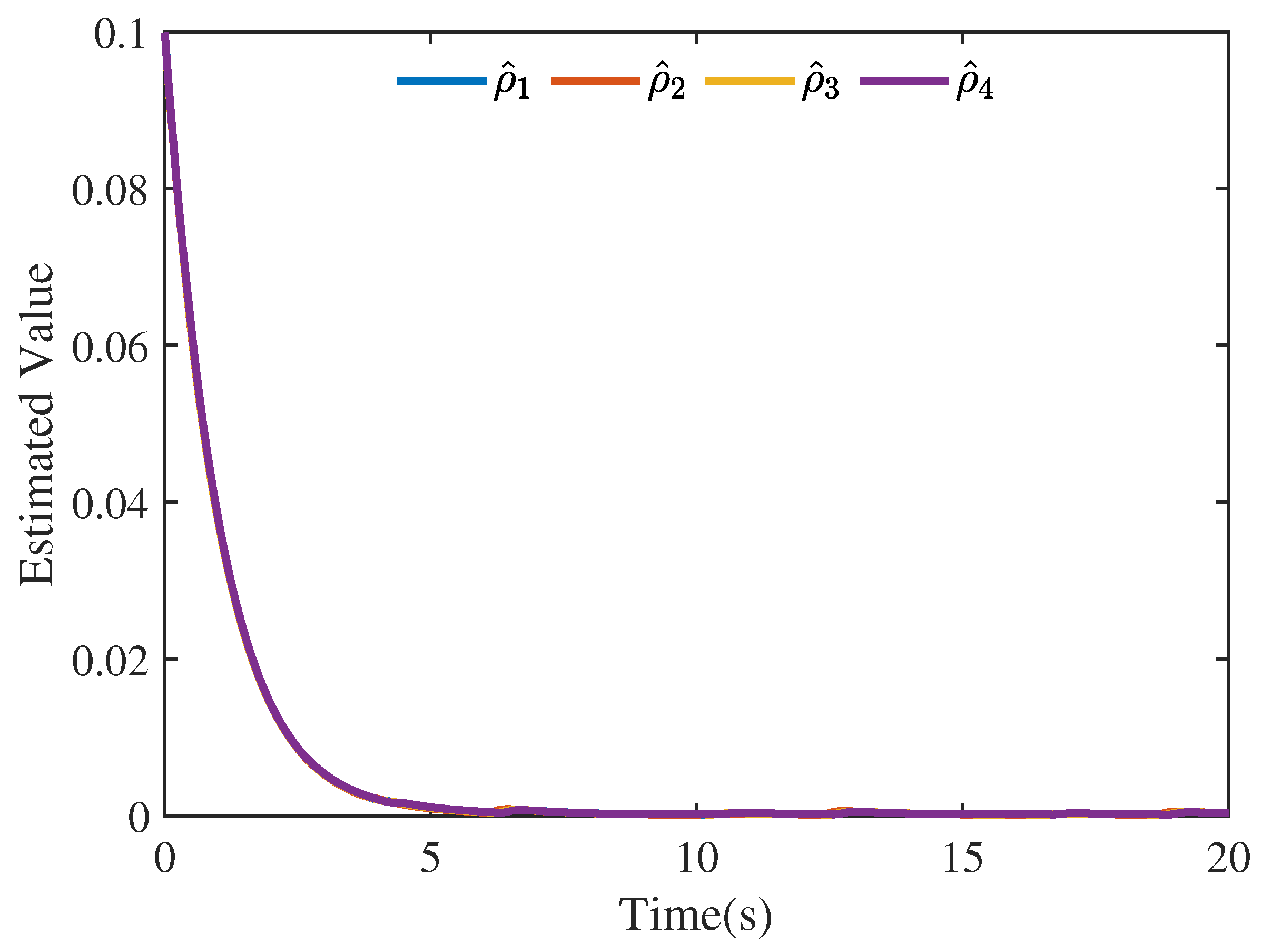

4.1. Numerical Simulation

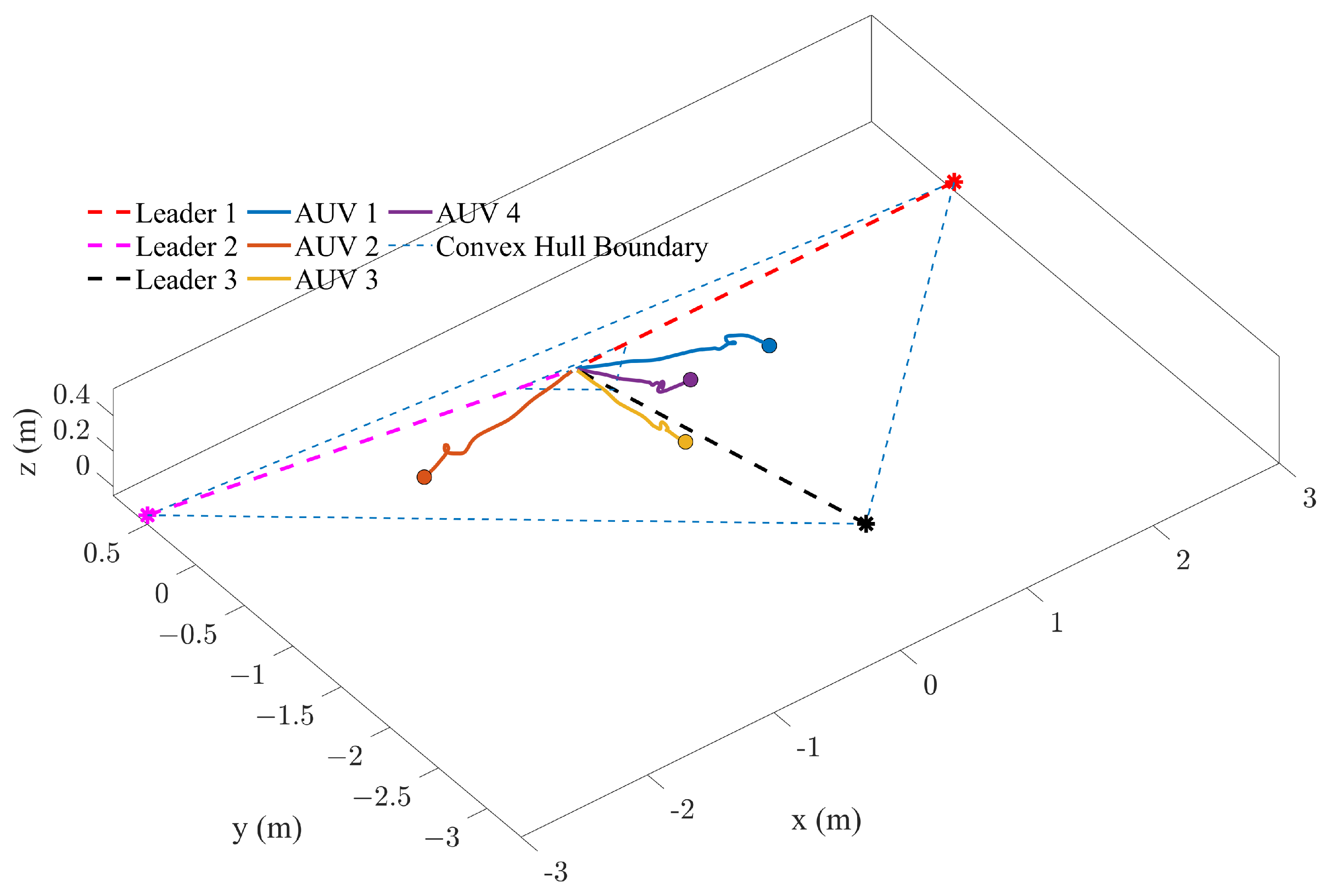

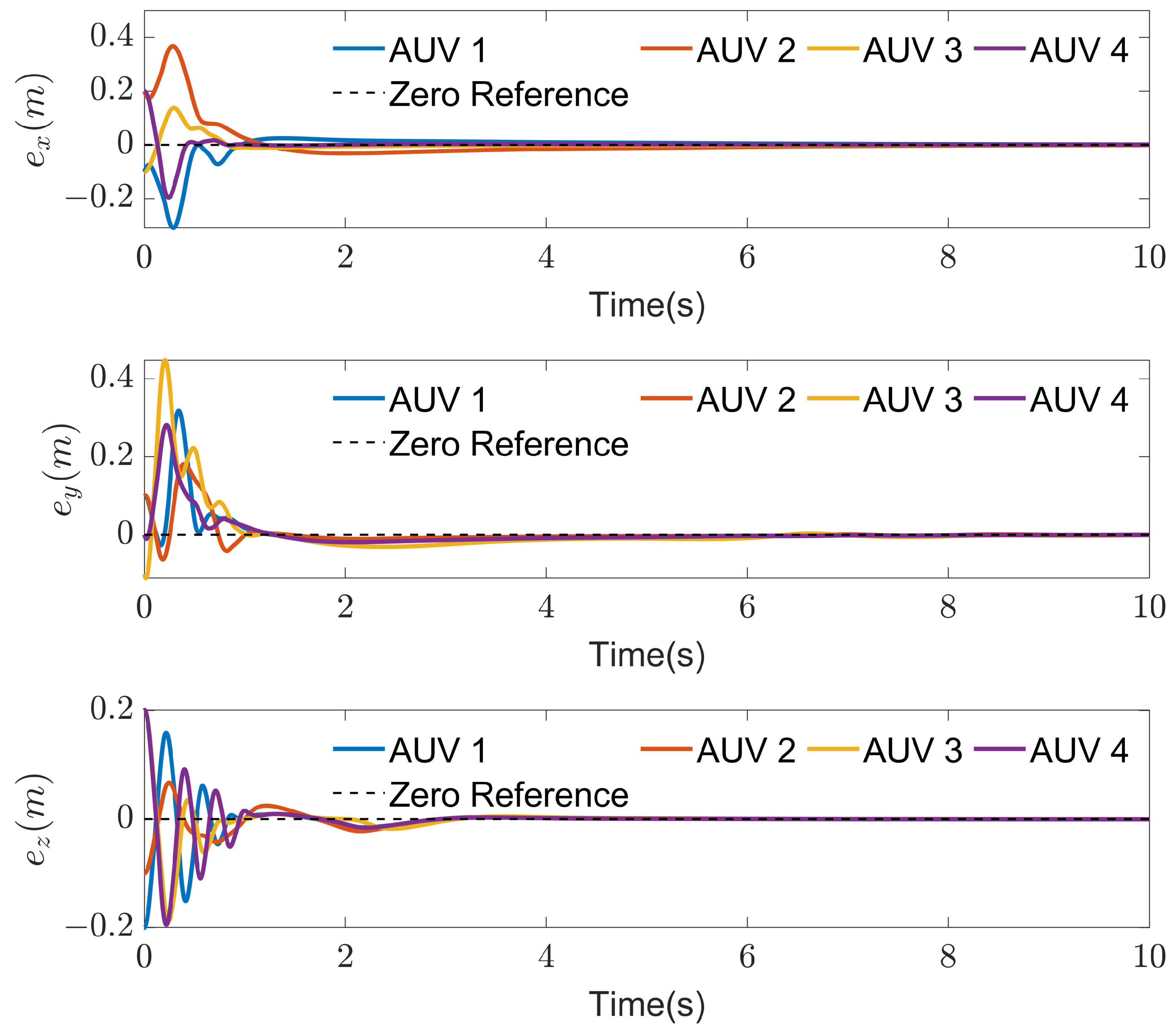

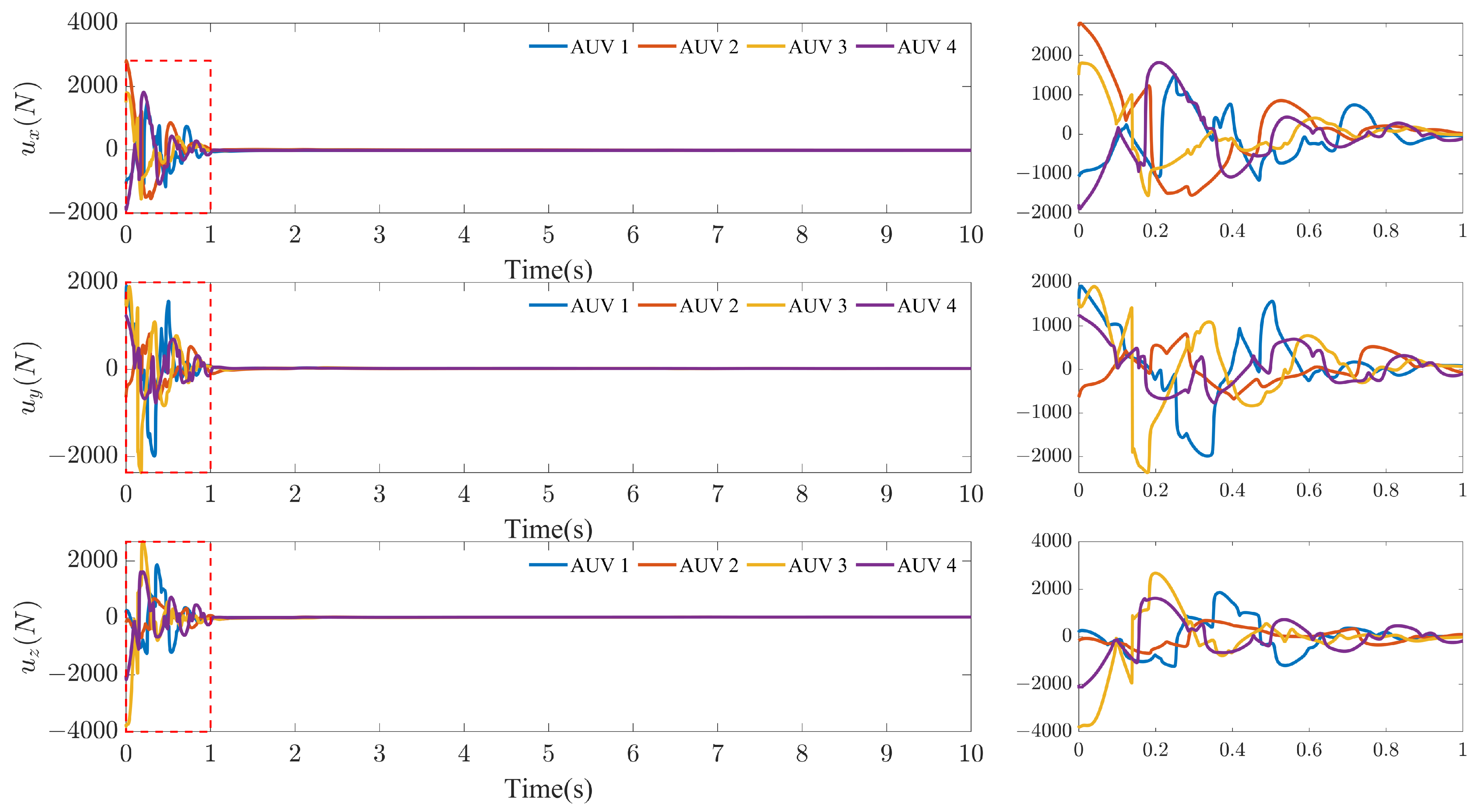

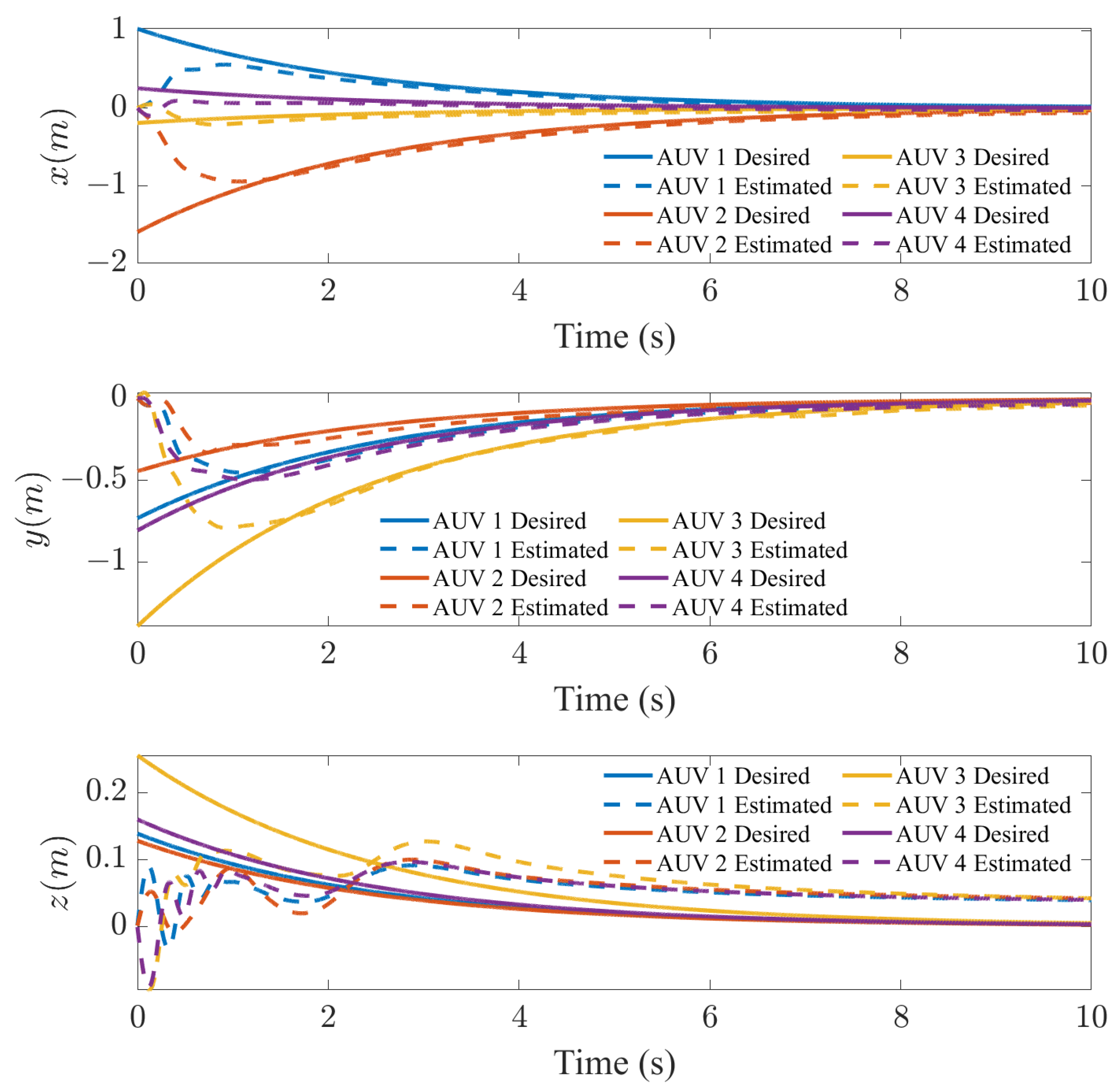

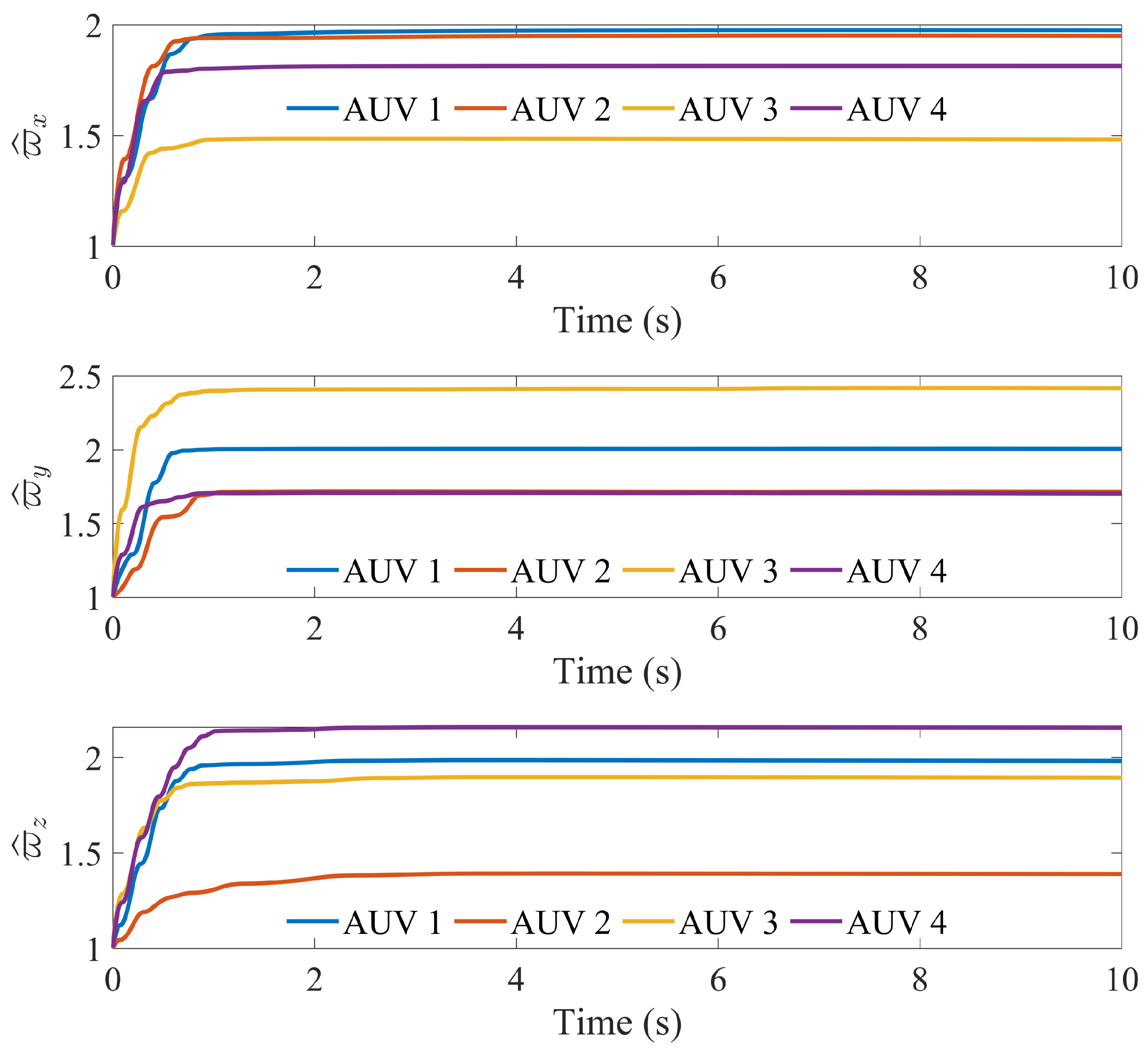

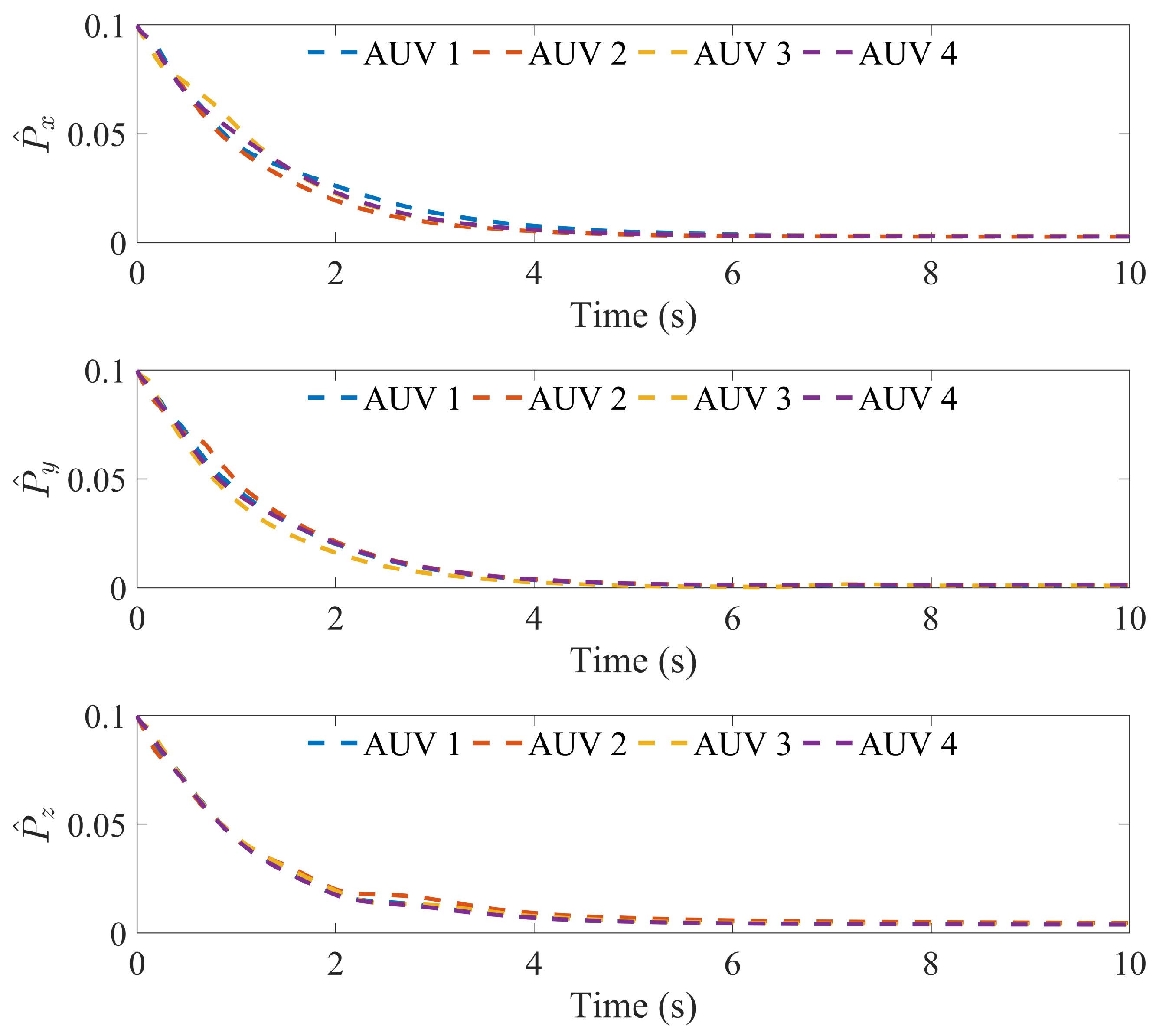

4.2. Simulation of AUV

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, K.; Luo, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, D. Research on Formation Control Method of Heterogeneous AUV Group under Event-Triggered Mechanism. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Precision Fixed-Time Formation Control for Multi-AUV Systems with Full State Constraints. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.; Ahmad, S.; Liaf, A.F.; Karimi, M.; Anmed, T.; Shawon, M.A. Oceanic challenges to technological solutions: A review of autonomous underwater vehicle path technologies in biomimicry, control, navigation, and sensing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 46202–46231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Ferrari-Trecate, G.; Egerstedt, M.; Buffa, A. Containment control in mobile networks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2008, 53, 1972–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharidis, T.; Kavallieratou, E. Underwater communication technologies: A review. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bose, N.; Brito, M.; Khan, F.; Thanyamanta, B.; Zou, T. A review of risk analysis research for the operations of autonomous underwater vehicles. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, W.; Xu, S. Distributed containment control with multiple dynamic leaders for double-integrator dynamics using only position measurements. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 57, 1553–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, H.; Ren, H.; Liang, H. Event-driven intelligent fault-tolerant containment control for nonlinear multiagent systems with unknown disturbances. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2025, 56, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zou, Y.; Meng, Z.; Ren, W. Distributed time-varying convex optimization for a class of nonlinear multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 65, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Lin, C. Distributed containment control for discrete-time nonlinear multiagent systems over dynamic topology with system uncertainties. IEEE Syst. J. 2025, 19, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, Y. Adaptive autonomous synchronization of a class of heterogeneous multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 2066–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yao, Z.; Deng, W.; Yao, J. Fixed-time adaptive neural network compensation control for uncertain nonlinear systems. Neural Netw. 2025, 189, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Park, J.; Hua, C.; Xu, H.; Li, Y. Distributed adaptive output feedback consensus for nonlinear stochastic multiagent systems by reference generator approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 12211–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, H.; He, W. Event-triggered adaptive bipartite containment control for stochastic multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 5843–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F. Fuzzy adaptive group formation-containment tracking control of nonlinear multiagent systems with intermittent actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Liu, C.; Niu, B.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D.; Yan, B. Prescribed performance adaptive containment control for full-state constrained nonlinear multiagent systems: A disturbance observer-based design strategy. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Ren, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, R. Distributed finite-time containment control for nonlinear multiagent systems with mismatched disturbances. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 6939–6948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Huang, T. Containment control of semi-Markovian multiagent systems with switching topologies. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 51, 3889–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, X. Fault-tolerant adaptive synchronization for high-order discrete-time multiagent systems with stochastic noises. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14833–14842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Liang, J. Security control of multiagent systems under denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 52, 4323–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Hu, G. Attack-resilient distributed convex optimization of cyber-physical systems against malicious cyber-attacks over random digraphs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Kong, L.; Li, G.; He, W. A single parameter-based adaptive approach to robotic manipulators with finite time convergence and actuator fault. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 15123–15131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y. Maximal tolerable fault set of robust MPC for passive fault tolerance with predefined performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, D.; Sheng, L. Active fault-tolerant control for stochastic fully actuated systems with local faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2025, 21, 4852–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.R.; Gao, M.; Huai, W.X.; Niu, Y.C.; Sheng, L. Fixed-time active fault-tolerant control for dynamical systems with intermittent faults and unknown disturbances. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 486, 129054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L. An adaptive fault-tolerant control scheme for heterogeneous multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Yang, Q.M.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Z.G.; Ge, S.S. Adaptive fault tolerant cooperative control for hybrid nonlinear multiagent systems via switching functional. Automatica 2025, 177, 112298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cui, L.; Gao, Z. Event-triggered interval observer fault detection and isolation for multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 4063–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Jawad, S. Stability analysis of the depletion of dissolved oxygen for the Phytoplankton–Zooplankton model in an aquatic environment. Iraqi J. Sci. 2024, 65, 2736–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Ren, W.; You, Z. Distributed finite-time attitude containment control for multiple rigid bodies. Automatica 2010, 46, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; San, P.; Ge, S.; Lee, T. Adaptive dynamic surface control for a class of strict-feedback nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis. In Proceedings of the 2009 American Control Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–12 June 2009; pp. 4482–4487. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Xue, H.; Liang, H.; Chen, D. Singularity avoidance adaptive output-feedback fixed-time consensus control for multiple autonomous underwater vehicles subject to nonlinearities. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2022, 32, 4401–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Huang, J.; Huang, J. Simulation Teaching of Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213475

Liu S, Zhang W, Huang J, Huang J. Simulation Teaching of Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. Mathematics. 2025; 13(21):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213475

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shangkun, Wangjin Zhang, Jingli Huang, and Jie Huang. 2025. "Simulation Teaching of Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems" Mathematics 13, no. 21: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213475

APA StyleLiu, S., Zhang, W., Huang, J., & Huang, J. (2025). Simulation Teaching of Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Containment Control for Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems. Mathematics, 13(21), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213475