Abstract

Category Theory provides us with a clear notion of what is an internal algebraic structure. This will allow us to focus our attention on a certain kind of relationship between context and structure; namely on categories (context) in which, on any object X, there is, at most, one algebraic structure of some type S.

Keywords:

internal structures; uniqueness of structures; context; varieties and categories; context vs. structure MSC:

08-11; 08A05; 08B05; 18A05; 18C40; 18E13; 20J99

1. Introduction

Let us begin by recalling that, in [1], an additive category is defined as a category enriched in the category of abelian groups which, in addition, has a zero object and a biproduct for each pair of objects. Actually, this is equivalent to saying that is a pointed category with products and such that any object X is endowed with a natural internal structure of abelian groups. An easy Eckmann–Hilton argument [2] shows, then, that this internal structure is necessarily unique and abelian. Accordingly, in an additive category, on any object X, there is, at most, one structure of (internal) abelian group.

For a long time, this result seemed absolutely natural and remained unquestioned. Later on, other and larger contexts emerged in which this same property held, as follows: unital and strongly unital categories [3], and subtractive categories [4]. Furthermore, again, this was accepted with no further questioning. Perhaps because, in the varietal occurrences of these kinds of categories, this uniqueness property arised because, and when, some term (a binary one) in the definition of the varieties in question became a homomorphism in this variety.

Similar situations for other algebraic structures were also known for a long time. For instance, it was clear that in a pointed Jónnson–Tarski variety, on any algebra X, there is, at most, one internal commutative monoid structure. The same property holds for the commutative and associative (=autonomous) Mal’tsev operations in the Mal’tsev varieties [5], and again the seemingly limpid varietal contexts supplied the same simple explanation as above for this phenomenon.

However, recently, we were led to observe that the uniqueness structure for abelian group objects still holds in the new context of congruence hyperextensible categories [6]. This, in restrospect, reminded us that the uniqueness of the autonomous Mal’tsev operations was already noticed (and still unquestioned) in the congruence modular varieties [7] as well.

This phenomenon of uniqueness of some kinds of algebraic structure is now clearly extended to much larger contexts than the ones of the two first paragraphs. The explanation by the structural nature of some kinds of terms in the definition of the varieties is no longer valid. So, it is no longer possible to take this uniqueness for granted and to keep it unquestioned. Whence the following:

Definition 1

([6]). A finitely complete category is called crystallographic with respect to a given algebraic structure S when, on any object X in , there is, at most, one internal algebraic structure of this kind. It will be called fully crystallographic when, in addition, any morphism between such objects is a S-homomorphism.

This terminology is chosen because, under the contextual pressure of the specific nature of a category (the context), the algebraic structure S becomes punctually as scarce as some crystals, appearing under specific geophysical pressures.

There are two extremal possible cases:

(i) On any object X in , there is one and only one S-structure; we then say that is intensively crystallographic with respect to the structure S.

(ii) The only S-structures are the terminal object 1 and its subobjects; we then say that trivializes the structure S.

Concerning the structure of the group, we noticed that any additive category is intensively crystallographic with respect to it. It is shown in Section 5.3 (see also [8]) that any Mal’tsev variety whose Mal’tsev term p satisfies the Pixley axiom [9] trivializes the Mal’tsev structure.

Finally, when a structure is such that any category of internal -structures in trivializes the structure S, we say that the structure trivializes the structure S.

The aim of this work is to produce examples and to establish the very first properties and general questionings about this notion of Algebraic Crystallography. Similarly to the geophysical crystallography, the algebraic one produces specific regularity and symmetry which are investigated in Section 6. Beyond this, still with an Eckmann–Hilton flavor, we shall show that the fundamental group of some topological algebraic structures is necessarily trivial, see Corollary 1 and Proposition 14. On the other hand, this work will lead to an unexpected outcome: we shall produce a variety which is crystallographic with respect to the structure of the abelian group and in which the punctual scarcity of this structure seems to be offset by a kind of multiplication, inside it, of the objects with such a structure. Indeed, the category of abelian objects in this variety will appear, as follows:

(i) to fully faithfully embed the category of abelian groups by a functor and in an independant way;

(ii) to faithfully “contain” any category K- of K-vector spaces, provided that the field K is not of characteristic 2, by a functor -.

So, the (set theoretical) abelian group underlying a K-vector space V will be split into two distinct objects: and inside the varietal abelian category .

We shall give an example of the same kind of object multiplication process in a non-pointed context, see Section 7.

The article is organised along the following lines. Section 2 is devoted to the first examples of algebraic crystallography in the unital setting. Section 3 is devoted to the same kind of examples in the Mal’tsev setting, a natural conceptual extension of the unital one. Section 4 introduces a more general type of fiberwise extension of the notion of algebraic crystallogaphy. Section 5 investigates the congruence hyperextensible and Gumm contexts from which the notion of algebraic crystallography emerged. Section 6 investigates the first properties of regularity and symmetry induced by the algebraic crystallography. Section 7 describes, in details, the unexpected outcome above-mentioned here. Section 8 deals with open questions.

2. First Examples from the Unital Setting

In this article, any category will be supposed finitely complete. The kernel equivalence relation of a map is denoted by . Given any algebraic structure S and any category , we denote by the category of internal S-structures in and by the canonical forgetful functor. The category is finitely complete as soon as so is , and its terminal object is the unique possible S-structure on the terminal object 1 of . The functor is clearly left exact and it reflects isomorphims.

Suppose now that the S-structure in question has no constant. Since, given any subobject of 1 in , we receive for any in a unique possible way, there is one and only one S-structure on this object J. Whence, a canonical fully faithful embedding from the fully faithful subcategory of the subobjects of 1 in which is such that is nothing but the inclusion .

2.1. General Unital Setting

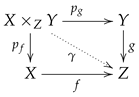

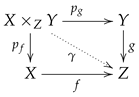

A unital category [3] is a pointed category such that the canonical pair of injections:

is jointly strongly epic, i.e., such that the only (up to isomorphism) subobject of containing and is .

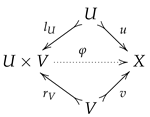

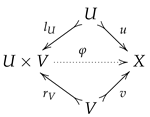

A pointed variety is unital if and only if it is a Jónnson–Tarski variety [8], i.e. if it has a unique constant 0 and a binary term + satisfying . So, the main examples of unital category are the categories and of unitary magmas and monoids. The unital setting appears to be the right one in which there is an intrinsic notion of commutative pairs of subobjects: given any pair , of subobjects, the unital axiom implies that there is at most one factorization :

making the previous diagram commute. So, when such a map does exist, the subobjects u and v are said to commute and the map is called the cooperator of the pair. This situation is denoted by . We can then follow the usual variations: a subobject is central when ; an object X is commutative when .

making the previous diagram commute. So, when such a map does exist, the subobjects u and v are said to commute and the map is called the cooperator of the pair. This situation is denoted by . We can then follow the usual variations: a subobject is central when ; an object X is commutative when .

By its cooperator , any commutative object X is endowed with a structure of internal unitary magma which turns out to be an internal commutative monoid. Moreover, any morphism between two commutative objects preserves these monoid structures. When this commutative monoid is an internal abelian group, the object X is said to be abelian. Whence, in this context, the two natural intrinsic fully faithful subcategories: of the commutative and abelian objects.

A collateral aspect of these observations was noticed as follows: in a unital setting, on an object X, there is, at most, one structure of internal unitary magma, but it was not thoroughly examined. We can now precisely assert that

Proposition 1.

A unital category is fully crystallographic with respect to the structure of unitary magma and, a fortiori, with respect to the structure of monoid, of commutative monoid and of abelian group.

According to the previous observations, this structure does exist on an object X in a unital category if and only if this object is commutative.

Example 1.

In the category (resp. ), an object X is endowed with a (unique) internal monoid structure if and only if the object X is a commutative unitary magma (resp. commutative monoid).

In the categories of groups, an object X is endowed with a (unique) internal monoid structure if and only if the group X is abelian.

In the categories of semi-rings or of rings, an object X is endowed with a (unique) internal monoid structure if and only if the multiplicative law is trivial.

Proof.

Let be a semi-ring, and ★ an internal monoid structure on this object. By Eckmann–Hilton, the laws + and ★ coincide. Now, + = ★ is a semi-ring homomorphism. Whence, . Setting , we receive . □

The same calculation and result remain obviously valid for any category of R-algebras (with R a ring). This is true, in particular, for the Lie algebras.

2.2. Special Unital Settings

We know that there are two extremal cases of unital categories [3]:

(i) The only commutative object is the terminal object 1.

(ii) Any object X is commutative.

The second case holds when the diagram is actually the diagram of the sum of X and Y; the pointed category is then called linear. The category of commutative monoids is linear.

The first case holds if and only if we have

The pointed category is then said stiffly unital.

The category of idempotent semi-rings is stiffly unital.

Proof.

Let be an idempotent semi-ring, and ★ an internal monoid structure on this object. By Eckmann–Hilton, the laws + and ★ coincide. Now, + = ★ is a semi-ring homomorphism. Whence, . Setting , we receive ; whence, . □

These two extremal situations give rise to two extremal cases of crystallography:

Definition 2.

A category trivializes (resp. strongly trivializes) a structure S when the subobjects J of 1 are the only objects to have a S-structure (resp. the terminal object 1 is the only one to have a S-structure).

A category is intensively crystallographic with respect to a structure S, when it is fully crystallographic with respect to S and when, moreover, on any object X, there is one (and thus only one) internal structure S.

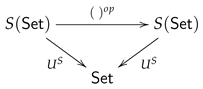

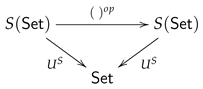

Accordingly, the category (resp. strongly) trivializes the structure S if and only if the canonical fully faithful embedding is an equivalence of categories, where is the fully faithful subcategory of the subobjects of 1 in (resp. if and only if the canonical embedding is an equivalence of categories where 1 is the discrete category with only one object). Also, the category is intensively crystallographic with respect to the structure S if and only if the forgetful functor is an equivalence of categories.

Any linear category is intensively crystallogaphic with respect to the structure of monoid. The category of boolean rings and the category of Heyting semi-lattices strongly trivialize the structure of monoid, see [8]; this is the case as well for the dual of the category of pointed sets and more generally for the dual of the category of pointed objects in when it is topos, see [3]. Finally, we come to the following:

Definition 3.

An algebraic structure Σ (resp. strongly) trivializes another algebraic structure S when, for any category , the category of internal Σ-structures in (resp. strongly) trivializes the structure S.

An algebraic structure S is paradigmatically crystallographic when, for any category , the category is intensively crystallographic with respect to the structure S itself.

So, the algebraic structure trivializes the structure S if and only if the canonical fully faithful embedding is an equivalence of categories. It strongly trivializes it if and only if the canonical embedding is an equivalence of categories. Since , the trivialization is clearly a symmetric relation between algebraic structures. On the other hand, an algebraic structure S is paradigmatically crystallographic if and only if the forgetful functor is an equivalence of categories. The most basic examples are the following ones:

(i) The structure of commutative monoid is paradigmatically crystallographic.

(ii) The structure of abelian group is paradigmatically crystallographic as well.

(iii) The structures of group and idempotent unitary magma strongly trivialize each other.

Proof.

The two first points are straightforward. Let be a group and ∗ the binary law underlying the internal unitary magma structure in . By Eckmann–Hilton, we receive . From , we receive , since this equality now holds inside a group. □

This leads to the following kind of corollary:

Corollary 1.

The fundamental group of a topological idempotent unitary magma is necessarily trivial. More generally, when a structure S is trivialized by the group structure, any topological S-structure produces a trivial fundamental group.

Proof.

The fundamental group functor from the category of pointed topological spaces to the category of groups preserves the terminal object and the binary product. So, it transfers the S-structure from to , which annihilates its image. □

2.3. Subtractive Categories

The concept of subtractive category, introduced in [4], is the categorical characterization of the pointed subtractive varieties in the sense of [10]. A pointed category is subtractive when, given any reflexive relation R on an object X, if factorizes through R, then so does . It was shown in [11] that, in this context, on any object X, there is, at most, one structure of subtraction [] of the abelian group; so, the induced inclusion functors are fully faithfull. We receive the following:

Corollary 2.

Any subtractive category is fully crystallographic with respect to the structure of subtraction and of abelian group.

3. Further Examples from the Mal’tsev Setting

The unital and Mal’tsev settings are related here by the below fiberwise characterization theorem. This will allow us to enlarge the set of examples of algebraic crystallography.

3.1. General Mal’tsev Setting

A Mal’tsev structure is a set X endowed with a ternary operation satisfying the Mal’tsev identities . We denote by the category of Mal’tsev structures. An affine structure is a Mal’tsev structure such that p is associative [] and commutative []. We denote by the category of affine structures.

A category is a Mal’tsev one when any internal reflexive relation is actually an equivalence relation [12,13]. Clearly, any category of internal Mal’tsev structures in is a Mal’tsev one. Let us recall the following characterizations:

Theorem 1.

The following conditions are equivalent:

(1) is a Mal’tsev category;

(2) Any sub-reflexif graph of an internal groupoid in is an internal groupoid;

(3) Any fiber of the fibration of points is unital;

(4) Any fiber of the fibration of points is subtractive.

The points (3) and (4) are grounded on the following definition: we denote by the category whose objects are the split epimorphisms in with a given splitting and morphisms the commutative squares between these data; by , we denote the functor associating its codomain with any split epimorphism. It is left exact and a fibration whose cartesian maps are the pullbacks of split epimorphisms; it is called the fibration of points. The fiber above Y is denoted by . The points (2) and (3) come from [8] and the point (4) from [4]. The following observations are important for our purpose:

Theorem 2.

Let be any Mal’tsev category. Then

(1) on any object X there is at most one internal Mal’tsev structure which is necessarily an affine one;

(2) on any internal reflexive graph in , there is, at most, one internal category structure, which is necessarily a groupoid one;

(3) any internal groupoid is necessarily an affine one.

The two first points come from [13]. In any category , an internal groupoid is affine when the associative Mal’tsev operation defined on the parallel arrows by is moreover commutative, and consequently produces an affine structure. The third point comes from [8] where the affine groupoids were introduced under the name of abelian groupoids. From the point (1), we receive immediately, the following:

Proposition 2.

Given any Mal’tsev category ,

(1) it is fully crystallographic with respect to the Mal’tsev structure and, a fortiori, with respect to the affine structure;

(2) any fiber is fully crystallographic with respect to the (abelian) group structure.

3.2. Special Mal’tsev Settings

Similarly to what happens in the unital setting and from the characterization Theorem 1, there are two extremal cases of Mat’sev categories: when (i) any fiber is stiffly unital; and when (ii) any fiber is linear.

In the first case, the category is said to be a stiffly Mal’tsev one, see [8], from which we shall recall the three first points of the following characterization:

Theorem 3.

Let be any Mal’tsev category. The following conditions are equivalent:

(1) The category is a stiffly Mal’tsev one;

(2) The only abelian equivalence relations are the discrete ones;

(3) Any fiber trivializes the group structure;

(4) The only internal groupoids are the equivalence relations.

The equivalence between (3) and (4) is shown below in Proposition 10. Accordingly, as follows:

Corollary 3.

A stiffly Mal’tsev category trivializes the Mal’tsev structure. A stiffly Mal’tsev category strongly trivializes the group structure.

Proof.

In a Mal’tsev category, an object X is affine if and only if the terminal map has an abelian kernel equivalence relation. So, our first assertion is a consequence of the point (2) of the previous characterization theorem which makes a monomorphism. An internal group object is always abelian in a Mal’tsev context; so, it is nothing but an affine object X with a global element . The second assertion is then straightforward. □

As for the second extremal case, let us recall the following:

Theorem 4.

The following conditions are equivalent:

(1) The category is a naturally Mal’tsev category;

(2) On any reflexif graph in , there is a unique structure of internal groupoid;

(3) Any fiber is linear;

(4) Any fiber is additive.

The equivalence between (1) and (2) is the ground result of [14] where a naturally Mal’tsev category is defined as a category in which any object X is endowed with a natural Mal’tsev structure. So, a naturally Mal’tsev category is a Mal’tsev one, and the natural Mal’tsev structure in question is then necessarily an affine one. Clearly, the category of affine structures and any category are naturally Mal’tsev ones. The equivalence between (1), (3), and (4) is in [3]. From that, we receive, immediately, the following:

Proposition 3.

(1) Any naturally Mal’tsev category is intensively crystallographic with respect to the Mal’tsev structure.

(2) The affine structure is paradigmatically crystallographic.

4. Fiberwise Extension of the Notion of Algebraic Crystallography

From (2) in Theorem 2 and in Theorem 4, we shall enlarge the set of examples of the crystallographic settings. For that, we shall think to the composition of arrows in a category or a groupoid as an algebraic structure on its underlying reflexive graph.

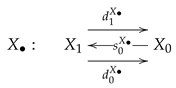

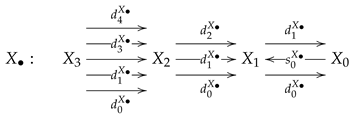

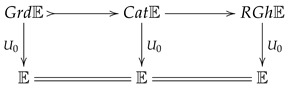

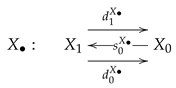

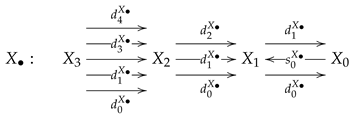

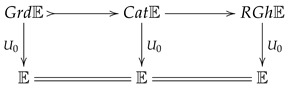

So, given any category , let us denote by the category of internal reflexif graphs in :

which is finitely complete and by , the left exact forgetful functor; it is a fibration whose cartesian map above is given by the inverse image along . We denote by the fibre above X; it has an initial object given by the discrete equivalence relation on X and a terminal one given by the indiscrete equivalence relation . Similarly, we shall denote by and the categories of internal categories and groupoids whose objects are the 3-truncated simplicial objects in (including all the natural degeneracy maps which do not appear in the following diagram):

which is finitely complete and by , the left exact forgetful functor; it is a fibration whose cartesian map above is given by the inverse image along . We denote by the fibre above X; it has an initial object given by the discrete equivalence relation on X and a terminal one given by the indiscrete equivalence relation . Similarly, we shall denote by and the categories of internal categories and groupoids whose objects are the 3-truncated simplicial objects in (including all the natural degeneracy maps which do not appear in the following diagram):

where, in the first case (categories), and are, respectively, obtained by the pullback of along and the pullback of along and where, in the second one (groupoids), any commutative square is a pullback. The same inverse image process as above makes fibrations the following forgetful functors:

where, in the first case (categories), and are, respectively, obtained by the pullback of along and the pullback of along and where, in the second one (groupoids), any commutative square is a pullback. The same inverse image process as above makes fibrations the following forgetful functors:

whose fibers, denoted, respectively, as and , have the same and as initial and terminal objects. Now, the points (2) of Theorems 2, 3 and 4 give rise to the following:

whose fibers, denoted, respectively, as and , have the same and as initial and terminal objects. Now, the points (2) of Theorems 2, 3 and 4 give rise to the following:

Corollary 4.

Let be a Mal’tsev category. Then any fiber :

(1) is fully crystallographic with respect to the structure of affine groupoid;

(2) trivializes the structure of groupoid if and only if is a stiffly Mal’tsev category;

(3) is intensively crystallographic with respect to the structure of affine groupoid if and only if is a naturally Mal’tsev category.

Proof.

Only the point (2) demands some precisions: in a Mal’tsev category, the subobjects of the terminal object in the fiber (namely the reflexive relations) are the equivalence relations. □

5. Congruence Hyperextensible and Gumm Categories

5.1. Congruence Modular Varieties and Gumm Categories

A congruence modular variety is a variety in which the modular formula holds for congruences:

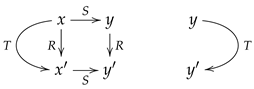

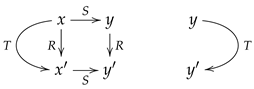

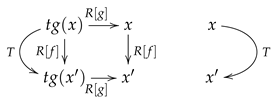

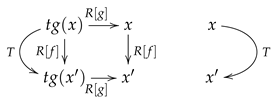

In [7], they were characterized in geometric terms by the validity of the Shifting Lemma: given any triple of equivalence relations such that , the following left hand side situation implies the right hand side one:

One of the main interest of the Shifting lemma is that it is freed of any condition involving finite colimits. So, thanks to the Yoneda embedding, it keeps a meaning in any finitely complete category . This led to the notion of Gumm category [15], defined by the validity of this Shifting Lemma. Any regular Mal’tsev category is a Gumm one. Let us recall, from [16], the following:

Proposition 4.

Let be any Gumm category. Then

(1) on any object X there is at most one affine structure;

(2) on any reflexive graph, there is at most one structure of category.

The first point was already noticed by Gumm in the congruence modular varieties. On the contrary to what happens in Mal’tsev ones, in Gumm categories, there are internal categories which are not groupoids. Now we receive the following:

Corollary 5.

Let be any Gumm category:

(1) It is fully chrystallographic with respect to the affine structure;

(2) Any fiber is fully chrystallographic with respect to the structure of category.

5.2. Conruence Hyperextensible Categories

On the model of Mal’tsev ones, Gumm categories have a characterization through the fibration of points [17]:

Theorem 5.

Given a category , the following conditions are equivalent:

(1) is Gumm category;

(2) Any fiber is congruence hyperextensible.

Definition 4.

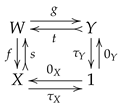

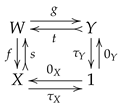

A pointed category is said to be congruence hyperextensible when given any punctual span in (=any commutative diagram of split epimorphisms):

Any equivalence relation T on the object W satisfying is such that .

Any equivalence relation T on the object W satisfying is such that .

This means that the following situation holds in W, as in the diagram above:

Any Jónsson–Tarski variety or any regular unital category is congruence hyperextensible. It is a fortiori the case for any regular pointed protomodular category [8], and thus for any Slomińsky variety [18]. Here are some examples of varieties which are outside of these classes:

Proposition 5.

Let be a pointed variety with ternary terms such that

Then, the variety is congruence hyperextensible but not a Jónsson–Tarski one.

Proof.

Starting with a punctual relation in as above and with an equivalence relation T on W such that . First, let us show that

. For all i with , we achieve:

. So: .

Then

, and finally

.

We also receive .

Whence

.

Finally

. Whence finally

.

The last assertion is proved when in [6]. □

We shall say that a congruence hyperextensible variety of the previous kind is a CHyper variety of type .

Proposition 6.

Any CHyper variety of type is of type .

Proof.

Let be a CHyper variety of type . Let us set the following:

These make the variety a CHyper variety of type . □

Recall, now, the main observation from [6]:

Proposition 7.

Let be a congruence hyperextensible category. Any subtraction s on an object X is the difference mapping associated with an internal group structure which is necessarily abelian. On any object X, there is, at most, one subtraction s; any morphism between objects with subtraction is a subtraction homomorphism.

Whence the following result which, as explained in the introduction, led to the notion of algebraic crystallography:

Corollary 6.

Any congruence hyperextensible category is fully crystallographic with respect to the structure of subtraction and of (abelian) group. Given a Gumm category , any fiber is fully crystallographic with respect to the (abelian) group structure.

5.3. Congruence Distributive Varieties and Categories

It is well known that any congruence distributive variety in which the following congruence formula holds below:

is congruence modular. Let us recall that a Mal’tsev variety is congruence distributive if and only if its Mal’tsev term p satisfies the Pixley axiom [9]. This is the case, in particular, for the category of Heyting algebras. In this section, we shall show that congruence distributive varieties and categories trivialize the group structure.

Definition 5.

A category is said to be weakly congruence distributive when the following implication holds below:

whenever the supremum of the pair of equivalence relations does exist.

We are going to show that any weakly congruence distributive category trivializes the group structure. For that, we first need the following:

Lemma 1.

Given any pullback in a category :

we receive among the equivalence relations on in .

we receive among the equivalence relations on in .

Proof.

(1) Let us show first that in any category , given any pair of objects, we receive . Let S be any equivalence relation on such that (i) and (ii) . Let and be any pair of maps from T to . We have by (i) and by (ii); whence, .

(2) Given any pullback as above and any equivalence relation S on S such that and . The same inclusions hold for , and now is an equivalence relation in the slice category . By (1) applied to the category , we receive . Whence, . □

Proposition 8.

Any weakly congruence distributive category trivializes the group structure. Any of the fibers trivializes the group structure; the category trivializes the associative Mal’tsev structure.

Proof.

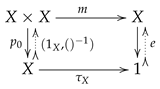

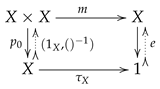

(1) Let us begin by showing that trivializes the group structure. So, let us denote by the binary operation associated with an internal monoid structure. It is a group structure if and only if the following downward square is a pullback:

and, consequently, is a monomorphism. The unit e produces the left hand side section and the upward pullback. Since both and are monomorphisms, we receive . Whence, . Accordingly, the morphism m is a monomorphism; being split (by ), it is an isomorphism. Coming back to the upward pullback, the morphism is an isomorphism as well. Accordingly, X is isomorphic to the terminal object.

and, consequently, is a monomorphism. The unit e produces the left hand side section and the upward pullback. Since both and are monomorphisms, we receive . Whence, . Accordingly, the morphism m is a monomorphism; being split (by ), it is an isomorphism. Coming back to the upward pullback, the morphism is an isomorphism as well. Accordingly, X is isomorphic to the terminal object.

(2) By the previous lemma, we can then reproduce this proof in any slice category or equivalently in any fiber .

(3) Now let be any internal associative Mal’tsev structure. We then receive an internal group structure on the object of the fiber , by setting . So, is an isomorphism; accordingly, is a monomorphism and X a subobject of 1. □

It is a fortiori in the case for any congruence distributive variety or category. In the Mal’tsev context, we have the converse with the following precisions:

Proposition 9.

Given any regular Mal’tsev category , the following conditions are equivalent:

(1) is weakly congruence distributive;

(2) Any fiber trivializes the group structure;

(3) The category is a stiffly Mal’tsev one.

Given any exact Mal’tsev category , the following conditions are equivalent:

(1) is congruence distributive;

(2) Any fiber trivializes the group structure;

(3) The category is a stiffly Mal’tsev one.

Proof.

The first equivalence comes from Lemma 2.9.10 and Proposition 1.11.34 in [8], while the second one is Theorem 2.9.11. □

Accordingly, a Mal’tsev variety is a stiffly Mal’tsev category if and only if it satisfies the Pixley axiom. Finally, let us observe that, more generally, we receive the following:

Proposition 10.

Given any category , the following conditions are equivalent:

(1) Any fiber trivializes the group structure;

(2) Any internal groupoid is an equivalence relation.

Such a category trivializes the associative Mal’tsev structure.

Proof.

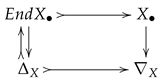

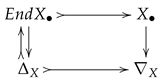

We shall work in the fiber which is a protomodular category [8]; accordingly, in this fiber, pullbacks reflect monomorphisms. Let be any groupoid in this fiber and consider the following pullback in :

where is the sub-groupoid of the endomorphisms of . It coincides with a group structure in the fiber . So, when (1) holds, the left hand side vertical map is an isomorphism, and consequently the right hand side one is a monomorphism, and thus is an equivalence relation. Conversely, any group structure in the fiber produces a groupoid which coincides with its endsome ; in other words, the upper horizontal arrow in the previous diagram is an isomorphism. So, if we suppose (2), namely that the right hand side vertical map is a monomorphism, so is the left hand side one. Being split, this same map is an isomorphism, and the group in question is trivial in . The last assertion is checked as in the previous proposition. □

where is the sub-groupoid of the endomorphisms of . It coincides with a group structure in the fiber . So, when (1) holds, the left hand side vertical map is an isomorphism, and consequently the right hand side one is a monomorphism, and thus is an equivalence relation. Conversely, any group structure in the fiber produces a groupoid which coincides with its endsome ; in other words, the upper horizontal arrow in the previous diagram is an isomorphism. So, if we suppose (2), namely that the right hand side vertical map is a monomorphism, so is the left hand side one. Being split, this same map is an isomorphism, and the group in question is trivial in . The last assertion is checked as in the previous proposition. □

Majority categories in the sense of [19] satisfy these conditions. In this context, we then receive another possible level of trivialization:

Definition 6.

A category weakly trivializes a structure S when the only S-structures in are given by some class of subobjects of 1.

Proposition 11.

When is a category such that any fiber trivializes the group structure, then any fiber weakly trivializes the structure of the groupoid.

6. First Observations on the Algebraic Crystallography

Similarly to the geophysical crystallography, the algebraic one produces specific regularity and symmetry.

6.1. Commutativity

The three first examples of crystallographic context (unital, additive, and Mal’tsev) are actually dealing with commutative structures. The reason is simple. Any of the structures S in question (monoid, group, or Mal’tsev structure) are endowed with a duality operator, namely an involutive isomorphism , making the following diagram commute, as follows:

The uniqueness involved by the definition of a crystallographic context implies that on an object X, any structure coincides with its dual.

6.2. A Universal and Invisible Example

In any category with terminal object and binary products, there is, on any object X, an invisible structure, namely the structure of co-unitary magma (with respect to the tensor structure ):

Indeed, a co-magma is just a pair of maps . It is co-associative if and only if and . It is co-unitary if and only if . Finally, there is a duality operator with , and a co-magma is commutative if and only if . So, the invisible co-unitary magma structure on X is a commutative comonoid structure. In this way, we receive the following:

Proposition 12.

Any category with terminal object and binary products is intensively crystallographic with respect to the structure of co-unitary magma which is necessarily a commutative comonoid structure.

In particular, the structure of commutative comonoid is paradigmatically crystallographic.

6.3. Trivializing Crystallographic Context

Certainly, as we already noticed, trivializing contexts are not so scarce. Let us add the following very special one, recalling from [20] the following:

Definition 7.

An implication algebra is a triple of a set, a binary operation and a constant such that

Lemma 2.

In any impication algebra we receive the following

Accordingly, any implication algebra has an underlying opsubtraction.

Proof.

First, setting in (2), we receive . Then set in the same (2). □

Let us denote by the category of implication algebras.

Proposition 13.

The category trivializes the structure of implication algebra. In other words, the structure of implication algebra is self-trivializing.

Proof.

Let ∗ give an internal implication algebra structure on in . It must be a -homomorphism, that is to satisfy the following:

Setting , we receive . So, we must have

Setting and , we receive ; so, is the terminal object in . □

According to the proofs of the previous lemma and proposition, the same result holds for the structure of implicative opsubtraction defined by and or, by duality, for the structure of opimplicative subtraction. Let be any Mal’tsev structure. Given any element , the binary operation defined by produces a subtraction on X with as constant. Then, p satisfies the Pixley axiom if and only if any subtraction is opimplicative. Incidentally, we receive the following:

Proposition 14.

The structure of opimplicative subtraction (resp. implicative opsubtraction) trivializes the structure of unitary magma. The fundamental group of a topological opimplicative subtraction (resp. implicative opsubtraction) is trivial. Accordingly, the fundamental group, at any point, of a topological Mal’tsev algebra satisfying the Pixley axiom is trivial.

Proof.

Let be a unitary magma, and s the internal opimplicative subtraction on it. We have . Taking , we receive . Then, take ; so, . The second assertion comes from Corollary 1. A topological Mal’tsev algebra is any object of a category - of internal -algebras in the category of topological spaces, where is a Mal’tsev variety, see [21]. The last assertion is then straightforward from the opimplicative subtraction . □

6.4. Paradoxical Aspect of the Notion

On the one hand, the kind of relationship “context vs structure” produced by the algebraic crystallography has a positive (=affirmative) aspect on the context side:

In this context, any object X has at most one occurrence of the structure of type S.

On the other hand, on the structure side, it could be thought as a kind of photographic negative:

Concerning this structure, there is no more than one occurrence on any object in that context.

So, a paradoxical question emerges as follows: could it be possible to extract some interesting positive information about a structure from the contexts in which this structure becomes so punctually scarce? Or, for example, and more precisely, what are we exactly learning about the notion of (abelian) group by knowing that congruence hyperextensive categories produce a crystallographic context with respect to it? In stricter words: could the context concretely inform us about the nature of the structure?

7. Some Very Large Abelian and Naturally Mal’tsev Categories

As said in the introduction, in this last section, we shall produce some constructions which seem to offset the punctual scarcity of a structure in a crystallographic context by a kind of multiplication of the objects bearing this structure inside this context, first in the pointed case of abelian groups, then in the non-pointed case of affine structures.

7.1. A Very Large Abelian Category

Consider the congruence hyperextensible variety defined by the only following three ternary terms and the following equations:

We receive a fully faithful functor defined in the following way: starting from a group , construct a -algebra on the set G by setting

By restriction, we receive a fully faithful embedding .

Now, consider any field K whose characteristic is not 2. We receive a faithful functor -: starting from a K-vector space V, construct a -algebra on the set V by setting

This algebra is made abelian by the -homomorphism .

So, the category of abelian objects in appears

(i) to fully faithfully embed the category of abelian groups by and in an independant way;

(ii) to faithfully “contain” any category K- of K-vector spaces, provided that the field K is not of characteristic 2, by -.

So, the (set theoretical) abelian group of a K-vector space produces two distinct objects, and , in the varietal abelian category .

7.2. A Very Large Exact Naturally Mal’tsev Category

We are now going to extend the previous kind of situation to a non-pointed context.

Consider the congruence modular variety defined by the only following three ternary terms and the following equations:

We receive a fully faithful functor defined in the following way: starting from an algebra in , construct a -algebra on the set X by setting

By restriction, we receive a fully faithful functor .

Now, consider any field K whose characteristic is not 2. We receive a faithful functor -: starting from a K-affine space X, construct an affine -algebra on the set X by setting

Here, is the barycentric mapping , where is the K-affine subspace of the K vector space of functions with finite support, and where is the linear map of the “total weight” of the function; the symbol represents the function defined by if and . The mapping is actually a K--homomorphism, and the affine structure on the algebra in the variety is then produced by the -homomorphism .

So, the category of affine structures in the variety appears

(i) to fully faithfully embed the category of affine structures by and in an independant way;

(ii) to faithfully “contain” any category K- of K-affine spaces, provided that the field K is not of characteristic 2, by -.

So, the (set theoretical) affine structure underlying a K-affine space produces two distinct objects, and , in the varietal naturally Mal’tsev category .

8. Open Questions

Of course, a natural question follows: is it possible to characterize, in some way, the structures which admit a crystallographic context or an intensive crystallographic context? Concerning the classical (= non-fiberwise) algebraic structures, we can, in addition, ask when the first situation implies the second one.

Another way to think of this question would be to ask are the commutative monoid and comonoid, abelian group, and affine structure the only ones to be paradigmatically crystallographic structures? Also, if it is the case, why is it so?

Another natural question was raised in Section 6.4: could it be possible to extract some interesting positive information about a structure S from the contexts in which this structure becomes so punctually scarce?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mac Lane, S. Category for the Working Mathematician; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1971; Volume 5, 262p. [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann, B.; Hilton, P.J. Group-like structures in general categories I. Math. Ann. 1962, 145, 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D. Intrinsic centrality and associated classifying properties. J. Algebra 2002, 256, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelidze, Z. Subtractive categories. Appl. Categ. Struct. 2005, 13, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.H. Malcev Varieties; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1976; Volume 554. [Google Scholar]

- Bourn, D. On congruence modular varieties and Gumm categories. Commun. Algebr. 2022, 50, 2377–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumm, H.P. Geometrical methods in congruence modular varieties. Mem. Am. Math. Soc. 1983, 45, 286. [Google Scholar]

- Borceux, F.; Bourn, D. Malcev, Protomodular, Homological and Semi-Abelian Categories, Kluwer, Mathematics and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 566, 479p. [Google Scholar]

- Pixley, A.F. Distributivity and permutability of congruences in equational classes of algebras. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1963, 14, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, A. On subtractive varieties. Algebra Universalis 1994, 31, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Janelidze, Z. Subtractive categories and extended subtractions. Appl. Categ. Struct. 2009, 17, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, A.; Lambek, J.; Pedicchio, M.C. Diagram chasing in Malcev categories. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1990, 69, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, A.; Pedicchio, M.C.; Pirovano, N. Internal graphs and internal groupoids in Mal’tsev categories. In Proceedings of the Canadian Mathematical Society Conference Proceedings, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 19–22 August 1992; Volume 13, pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, P.T. Affine categories and naturally Malcev categories. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1989, 61, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Gran, M. Normal sections and direct product decompositions. Commun. Algebra 2004, 32, 3825–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D.; Gran, M. Categorical aspects of modularity. In Galois Theory, Hopf Algebras, and Semiabelian Categories; Janelidze, G., Pareigis, B., Tholen, W., Eds.; Fields Institute Communications: Providence, RI, USA, 2004; Volume 43, pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bourn, D. Fibration of points and congruence modularity. Algebra Universalis 2005, 52, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomiński, J. On the determining of the form of congruences in abstract algebras with equationally definable constant elements. Fundam. Math. 1960, 48, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefnagel, M.A. Majority categories. Theory Appl. Categ. 2019, 34, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.C. Semi-boolean algebra. Math. Vesnik 1967, 4, 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, P.T.; Pedicchio, M.C. Remarks on continuous Malcev algebras. Rend. Univ. Trieste 1993, 25, 277–297. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).