Abstract

This study introduces SHAP-Rule, a novel explainable artificial intelligence method that integrates Shapley additive explanations with fuzzy logic to automatically generate interpretable linguistic IF-THEN rules for diagnostic tasks. Unlike purely numeric SHAP vectors, which are difficult for decision-makers to interpret, SHAP-Rule translates feature attributions into concise explanations that humans can understand. The method was rigorously evaluated and compared with baseline SHAP and AnchorTabular explanations across three distinct and representative datasets: the CWRU Bearing dataset for industrial predictive maintenance, a dataset for failure analysis in power transformers, and the medical Pima Indians Diabetes dataset. Experimental results demonstrated that SHAP-Rule consistently provided clearer and more easily comprehensible explanations, achieving high expert ratings for simplicity and understanding. Additionally, SHAP-Rule exhibited superior computational efficiency and robust consistency compared to alternative methods, making it particularly suitable for real-time diagnostic applications. Although SHAP-Rule showed minor trade-offs in coverage, it maintained high global fidelity, often approaching 100%. These findings highlight the significant practical advantages of linguistic fuzzy explanations generated by SHAP-Rule, emphasizing its strong potential for enhancing interpretability, efficiency, and reliability in diagnostic decision-support systems.

Keywords:

explainable artificial intelligence; Shapley additive explanations; fuzzy rules; linguistic variables; diagnostics MSC:

68T27

1. Introduction

State-of-the art machine learning (ML) has significantly improved diagnostic performance across diverse fields. Neural networks and ensemble-based models are one of the most commonly used approaches. They are applied in diverse areas, such as industrial predictive maintenance, high-voltage power equipment diagnosis, and medical diagnostics. Despite their accuracy, the opaque nature of these models complicates their integration into decision support systems (DSS). This is particularly evident when decision-makers (DMs) must act swiftly and explain their decisions transparently to colleagues. Thus, in diagnostic tasks, the ability to quickly understand and clearly communicate model-driven decisions is critical.

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) addresses the challenge of limited interpretability in complex machine learning (ML) models. Among the most established approaches are Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) [1] and local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) [2], which generate quantitative feature importance vectors to clarify model behavior. SHAP, in particular, has become widely applied in diagnostic tasks for industrial and power equipment [3,4,5,6]. Although these numeric explanations provide valuable insights, studies indicate that their direct interpretation remains difficult in domains where decisions must be rapidly understood and communicated [7,8].

DSS that use fuzzy logic are recognized as much more transparent and interpretable. For example, studies [9,10,11] substantiate that IF-THEN rules are clear and understandable for users; therefore, the authors call for the use of fuzzy logic to implement XAI principles.

The authors of this study have put forward a hypothesis. Namely, this research underlines the fact that certain measures might significantly enhance interpretability and usability of ML-based diagnostic systems. Therefore, we propose automatically translating numeric SHAP into concise, human-understandable fuzzy linguistic rules. Firstly, the linguistic nature of these explanations facilitates rapid comprehension. Secondly, it also supports effective communication among stakeholders in critical decision-making processes.

The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- A novel XAI method, termed SHAP-Rule, is proposed to automatically convert numeric SHAP values into interpretable fuzzy linguistic rules with quantified activation strength. Its novelty lies in the automated generation of linguistic rules directly from feature attributions without manual definition, ensuring consistent interpretability for any model type.

- A rigorous comparative analysis is conducted, benchmarking SHAP-Rule against standard numeric SHAP and AnchorTabular explanations across multiple datasets.

- The methodological innovation lies in bridging quantitative feature attributions and symbolic fuzzy representation through a unified, computationally efficient pipeline that automatically converts SHAP outputs into interpretable linguistic rules.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 (Related Works) discusses existing research on explainable AI, SHAP-based methods, anchor explanations, and fuzzy logic approaches and highlights their limitations. Section 3 (Methodology) provides a formal description of the proposed SHAP-Rule method. It details fuzzy rule generation and activation computation. Section 4 (Experimental Setup) describes the datasets, models, and evaluation metrics used in our experiments. Section 5 (Results) presents and analyzes the comparative experimental outcomes. Section 6 (Discussion) critically evaluates the strengths, limitations, and practical implications of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 7 (Conclusions) summarizes the findings and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Related Works

2.1. Local Rule-Based Explanation Methods

Multiple ML techniques generate human-readable IF–THEN rules, which explain model decisions on structured data. For example, Ribeiro et al. have introduced anchors—model-agnostic rules offering minimal, high-precision conditions. They, in turn, ensure consistent local model predictions [12]. Anchors are intuitive for diagnostic tasks, which require quick, transparent decision-making. Nevertheless, their crisp conditions might oversimplify continuous variables.

Precision and simplicity make anchors appealing for diagnostic decision-making. For example, an expert might favor an explanation like “IF you find symptoms (or defect signs) X and Y, THEN the diagnosis (or state of the equipment) is Z” with a guarantee of model consistency. However, anchors typically rely on crisp feature discretization.

RuleFit integrates rules extracted from decision-tree ensembles into sparse linear models [13]. It combines interpretability and accuracy by creating weighted IF–THEN rules. However, without careful regularization there occurs a risk of complexity.

Probabilistic rule learning approaches also aim to represent compact, interpretable models. Bayesian rule lists (BRLs) introduce compact probabilistic lists of decisions, striking a balance between interpretability and accuracy. BRLs have been successfully applied in medical diagnostics as they offer concise, human-readable sequences of decisions [14]. However, computational complexity and crisp (sharp) thresholds limit their applicability. The technology might not capture gradations in risk unless additional rules are introduced.

The method submodular pick (SP-LIME) selects representative local explanations, approximating global understanding [2]. SP-LIME effectively summarizes model behavior with a small rule set but still provides separate, not unified, explanations.

Earlier studies focused on extracting interpretable rule-based surrogates for black-box models. A classic example is TREPAN, which operates on a decision tree algorithm that replicates the trained neural network’s predictions [15]. Despite the fact that the resulting trees may be transparent; they might become too complex. In this case, it might limit their practical use for particular diagnostic problems. Moreover, TREPAN’s rules are deterministic and crisp.

To summarize, rule-based explanation methods address the problem of interpretability, offering an intuitive symbolic description of model decisions. This technology has shown itself in domains such as healthcare; however, it often gives rigid explanations that may miss some important nuances. On the other hand, such methods generally operate independently of feature-attribution methods like SHAP, which leaves an opportunity to combine the strengths of both approaches.

One common strategy involves clustering SHAP values to discover subpopulations driven by distinct feature sets. Clustering provides high-level, understandable group explanations but risks oversimplifying individual cases. The main limitation is that clustering is an unsupervised summarization. Choosing the number of clusters and interpreting each cluster still requires expert judgment. At the same time, important nuances might be lost when generalizing individual explanations to cluster “profiles.”

Grouping of features when assessing their significance has been proposed in some studies [16,17]. It is performed by modifying the original SHAP algorithm to calculate the significance of features.

A promising direction is the use of large language models for subsequent processing of the results of SHAP-based explanations. At present, various articles describe this direction with concept level-based ideas [7,9,18,19]. Another approach is represented by the use of universal large language models, such as Mistral 7b (7.3 billion parameters) [20] and DeepSeek v3 (671 billion parameters) [21]. The main considered tasks are those where the models have a sufficient amount of context. These models form an explanation based on the significance of features without additional training (cybersecurity [20] and spam classification [21]). Although LLM-aided explanations are being explored, they are still rarely used as the primary approach for explaining tabular classification models in diagnostic DSS (where attribution-based methods remain standard) and, when LLMs are applied, task-specific fine-tuning and careful prompt design are often required, demanding additional human effort and significant computational resources. In the area of combining LLMs and SHAP-based algorithms, there is also a fundamentally different task—the use of SHAP to improve the explainability of LLMs [22].

LLM-aided explanations use large language models to verbalize or generate natural-language rationales for model behavior—and, increasingly, to attribute evidence inside LLMs themselves—delivering high linguistic fluency but posing open challenges around faithfulness, reproducibility, and computational cost [23].

2.2. Fuzzy Logic and Linguistic Explanations in XAI

Fuzzy inference systems provide interpretable IF–THEN rules using linguistic variables and allow intuitive explanations in diagnostic tasks [9,24]. These systems translate numeric inputs into human-friendly terms (e.g., “high temperature”) enhancing transparency and user trust [10,22]. Applications diagnostics demonstrate the benefits of fuzzy logic by enabling decision-makers to rapidly understand model predictions [9,24,25]. For instance, hybrid deep-learning–fuzzy approaches have effectively explained sensor data predictions in industrial fault diagnosis [25].

However, traditional fuzzy models often require extensive expert involvement in defining rules and membership functions. Additionally, as the number of features grows, fuzzy systems might become too complex, compromising their interpretability and practical usability [10,26].

The use of fuzzy logic to explain machine learning models is a separate area of research. The main idea is to display the rules that are triggered when processing each specific instance of input to the model. SHAP and LIME methods are also used to identify the most significant features [22,27]. In Ref. [28], fuzzy rules extract informative biomarkers. Another study [29] describes the architecture of a deep neural network learning model.

Conventional fuzzy systems usually serve as standalone interpretable models rather than post hoc explainers for trained black-box models. This limits their scalability in complex diagnostic tasks. The proposed SHAP-Rule approach bridges this gap by integrating numeric SHAP feature attributions with fuzzy linguistic rules, thus combining quantitative precision with symbolic interpretability.

2.3. Identified Gaps of Existing Studies

There are several limitations and gaps which were identified in the existing studies:

- Current rule-based explanation methods such as Anchors, RuleFit, and TREPAN often use crisp rules and thresholds, which struggle to capture continuous feature variations effectively. Thus, it compromises interpretability in terms of diagnostics.

- Numeric feature attribution methods, like SHAP, provide accurate quantitative explanations. However, their purely numeric outputs remain challenging for domain experts. Outputs require immediate comprehension to be interpreted rapidly, especially in critical scenarios.

- Fuzzy logic-based systems traditionally demand significant expert input for rule creation, hindering their scalability and practicality in complex, high-dimensional diagnostic tasks.

These identified limitations motivate development of an integrated method, such as the proposed SHAP-Rule. Its aim is to convert numeric SHAP into concise, interpretable fuzzy linguistic rules, effectively bridging the gap between numeric precision and human interpretability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of SHAP-Rule Method

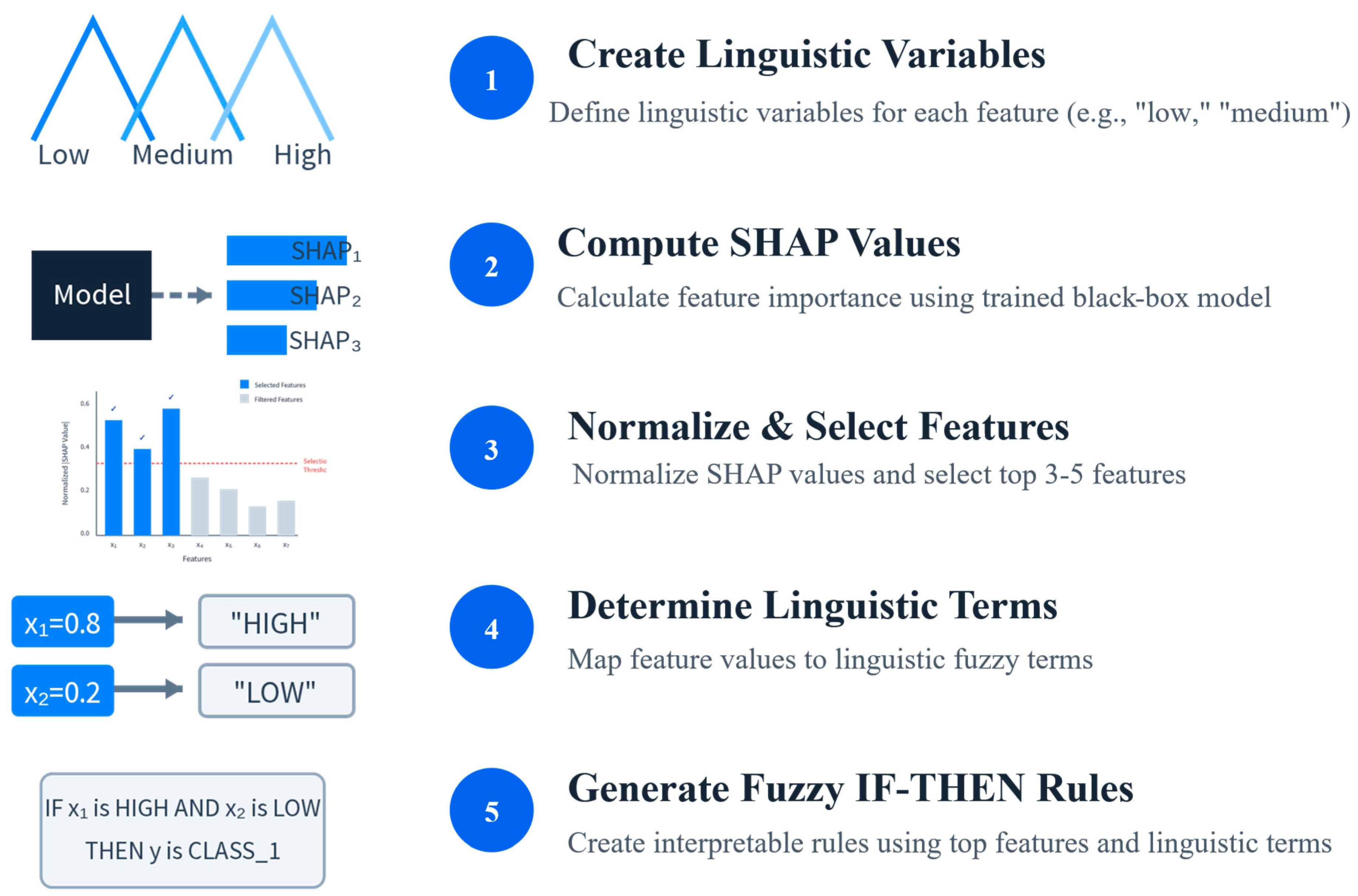

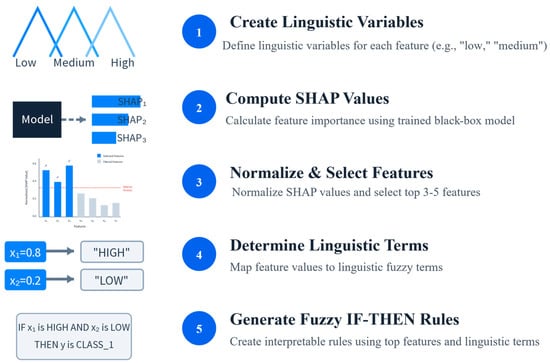

The rationale behind choosing SHAP is its strong theoretical grounding in cooperative game theory, which provides consistent and accurate feature attributions. Fuzzy logic can provide transparent and clear interpretation for the expert-user of the DSS [30,31]. Combining SHAP with a fuzzy linguistic representation allows us to exploit the numerical precision of SHAP and the interpretability of fuzzy logic. The proposed SHAP-Rule method represents five main stages (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The general pipeline.

- (Preparatory stage.) Create a number of linguistic variables for each feature.

- Compute numeric SHAP feature importance values using a trained black-box model for a processed input sample.

- Normalize the SHAP values and select the top 3–5 features with the greatest absolute values of SHAP-based feature importance.

- Determine linguistic fuzzy terms for each feature of the processed input sample.

- Generate fuzzy IF–THEN rules using the selected top SHAP features and linguistic fuzzy terms.

Note that SHAP-Rule is a post hoc explanation layer rather than a hierarchical fuzzy inference system; it emits one local linguistic rule per instance to explain a black-box prediction.

3.2. Automatic Generation of Fuzzy Terms via Arcsinh-Based Quartile Partitioning

To transform numeric SHAP values into linguistic terms, we propose to automatically define seven fuzzy terms: “extremely low,” “low,” “below average,” “average,” “above average,” “high,” and “extremely high”.

The boundaries are calculated in a transformed scale to remove strong asymmetry and the “long tail” of the feature distribution. Then the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation is applied to each feature xi of set X (a training part of the dataset used):

which handles skewness and negative values. We do not use logarithms because feature values can be negative.

Let

and define the interquartile range IQR = Q3 − Q1.

Also let

Compute the outer points as

to ensure “extreme” terms capture outliers.

The resulting boundaries are

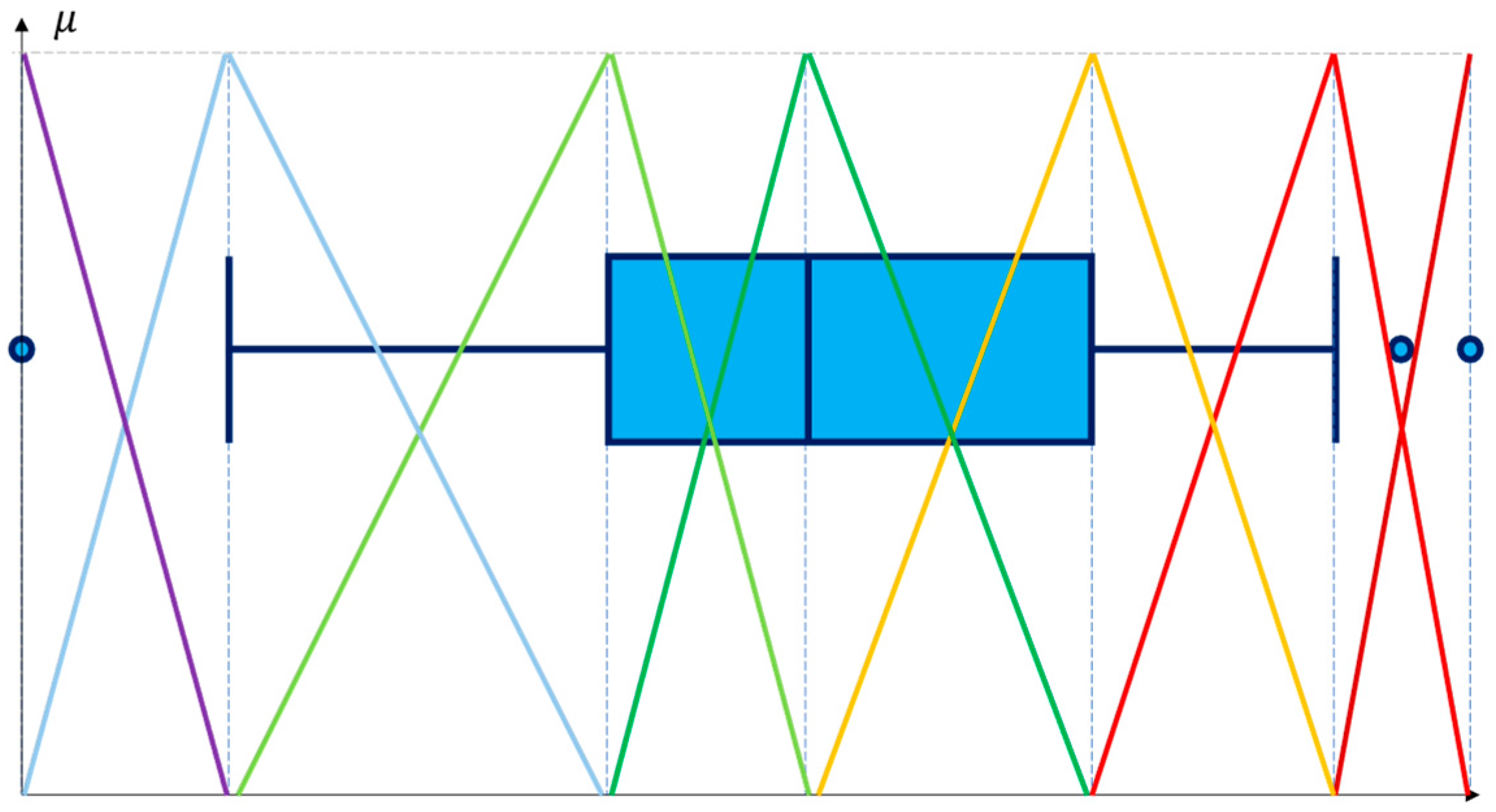

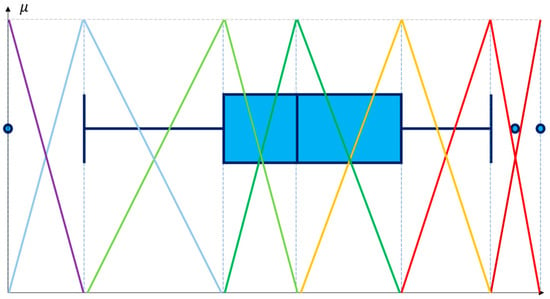

The statistical boundary points for fuzzy linguistic terms are determined using Tukey’s standard practice (1.5·IQR criterion) [32]. It is widely recognized for effective outlier detection. Employing this criterion ensures that extreme linguistic terms (“extremely low” and “extremely high”) accurately capture and represent atypical data points. Thus, the interpretability and robustness of generated fuzzy rules are enhanced. Even if certain boundaries are numerically identical, all seven points are maintained to ensure consistency in the representation of terms. Figure 2 illustrates membership functions.

Figure 2.

The relationship between the statistical distribution of a feature and the membership functions.

Then each boundary is converted back to the original scale of the feature via the inverse arcsinh (i.e., hyperbolic sine):

It is necessary to ensure that the list of boundaries, B, contains only terms with strictly distinct boundaries remain (e.g., if there are no outliers, “extremely low” and “low” collapse into the same numeric value). This simple algorithm is used to produce a concise set of non-overlapping fuzzy terms.

It takes a list of seven numeric boundary values and returns a dictionary mapping each linguistic term to its corresponding boundary. It automatically removes any “redundant” terms whose boundaries coincide with an adjacent term:

- “Average” term is always included (the median).

- For each index to the left of the median, i = 2, 1, 0. A member with an index i is included only if Bi < Bi+1. If two adjacent boundaries are equal, the loop stops, and no more left-side terms are added.

- The right part of the median of the boundaries is processed in a similar way.

3.3. Fuzzy Membership Function Construction

Triangular membership functions are constructed automatically for each linguistic term defined by three boundary points, a, b, and c, where b is the peak of the triangle:

This ensures intuitive interpretability, clearly defining membership degrees within the linguistic terms.

As a result, a set of fuzzy membership functions MF is formed automatically.

3.4. Generation of Fuzzy IF–THEN Rules

Taking into account the SHAP value ϕj for a particular prediction and the associated membership function μj, we select the top q features based on the normalized absolute SHAP importance:

Let be the normalized SHAP values for all n features, and denote by π a permutation of {1, …, n}, so that

Let K be the maximum allowed number of features and let T ∈ (0,1] be the cumulative magnitude threshold and define

and then set

The selected feature indices are

In other words, the steps are as follows:

- Sort features by descending |wj|.

- Find the smallest m so that .

- Take q = min(m, K) top features.

For example, if = 0.91 and T = 0.90, then m = 1, so q = 1 (only that feature is selected).

3.5. Activation Strength of Rules

The activation strength α of the resulting fuzzy rule is computed using a weighted geometric mean:

This provides a concise yet expressive measure of rule validity and strength.

3.6. SHAP-Rule Algorithm (Pseudocode)

A formalized description of the SHAP-Rule algorithm is given below (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1. SHAP-Rule Algorithm | |

| Input: Trained model M, set of fuzzy membership functions MF, instance x, number of top features q and threshold T. | |

| Output: Fuzzy IF–THEN rule | |

| Begin ACO-JSS Algorithm | |

| 1 | Compute SHAP values φ = SHAP(M, x) |

| 2 | Normalize SHAP values wj. |

| 3 | Select top q features based on normalized SHAP values. |

| 4 | Compute membership degrees for each feature i in top features: MF(i, xi). |

| 5 | Formulate fuzzy rule: (feature1 is term1 AND … AND featureq is termq) : M(x). |

| 6 | Calculate activation strength α. |

| End ACO-JSS Algorithm | |

Step-by-step commentaries to the Algorithm 1:

- (1)

- Start with a trained model and a specific instance to explain. Compute SHAP contributions for that instance—i.e., how strongly each feature influenced the model’s decision.

- (2)

- Normalize SHAP values to apply the next step (top features selection).

- (3)

- To keep the explanation short, preserve only the most influential features: sort features by contribution, take them from the top until a cumulative importance threshold T is reached, and cap the total number by K. This guarantees a compact, readable rule.

- (4)

- Convert each selected feature’s numeric value into a human-friendly term (e.g., “very low,” “below average,” “average,” “above average,” “high,” “very high”). These terms are created automatically from the training data using a robust transformation and quartile-based boundaries; triangular membership functions define how strongly the value matches the term.

- (5)

- Assemble everything into a single IF–THEN sentence: “IF (feature1 is term1) AND (feature2 is term2) … THEN class = model’s prediction.” In other words, the numeric SHAP vector becomes a concise linguistic rule.

- (6)

- Compute a single “activation” score for the rule that reflects both (a) each feature’s importance and (b) how strongly the current value fits its term. Intuitively: the more important the feature and the stronger its membership, the higher the activation.

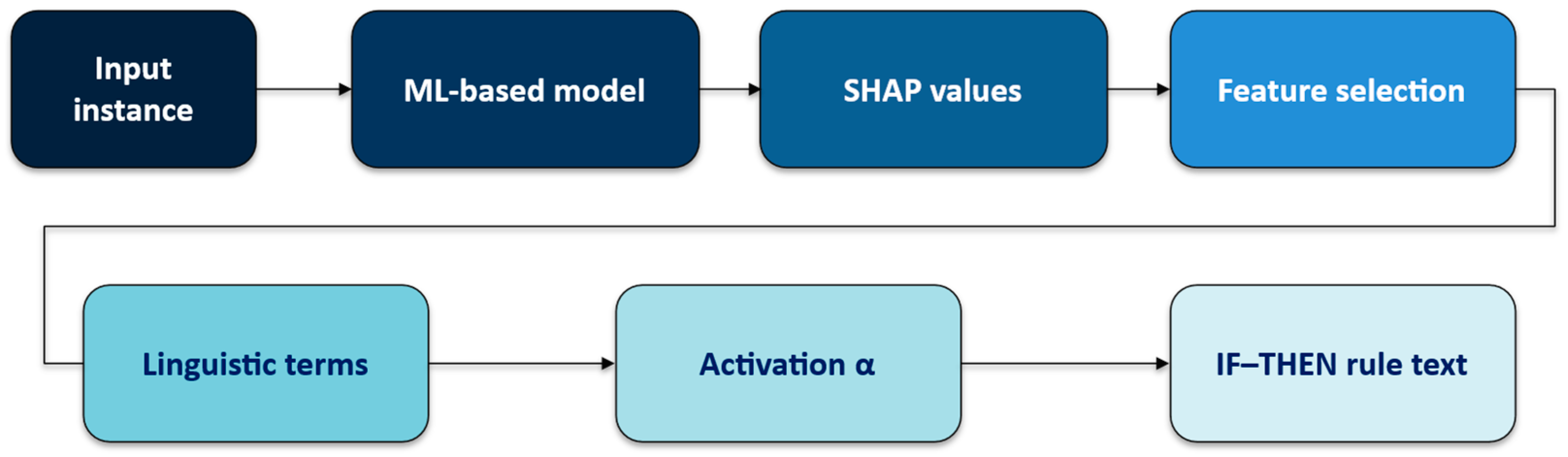

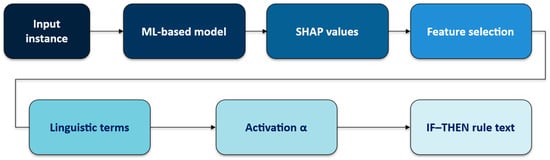

SHAP-Rule is not a hierarchical fuzzy inference system (e.g., Mamdani or Takagi–Sugeno). It is a post hoc, single-layer linguistic explanation head attached to a trained black-box classifier. The classifier produces the prediction; SHAP-Rule derives a compact fuzzy IF–THEN rule that explains this local decision (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pipeline of SHAP-Rule-based explanation generation.

The outcome of the SHAP-Rule Algorithm (3.6) is that there is one local rule per input instance x; no multi-layer fuzzy reasoning or global rule base is constructed. We illustrate the algorithm on a test-set instance shown in Section 5 (“Text formats of explanations”).

3.7. Benchmark Methods for Comparison

For empirical validation, SHAP-Rule (“SHAP-R”) is compared against the following:

- TreeSHAP (for tree-based ensembles, SHAP was computed using the TreeExplainer algorithm, which is an efficient implementation of the classical SHAP method for tree models [33]) (“SHAP”).

- SHAP (TreeExplainer) with a limitation on the number of displayed features, according to the same rules as described (“SHAP-L”).

- AnchorTabular, which generates local IF–THEN rules with high precision for model predictions [12] (“AnchorT”).

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets

The experiments used three diverse datasets, each representing a different field of diagnostics. Two of them involved equipment diagnostics and one of them was from the medical field. All three were specifically meant to test the applicability of the approach in different domains.

- CWRU Bearing dataset [34]. It is a data-driven fault diagnosis dataset containing ball Bearing test data for normal and faulty bearings.

- Domain: equipment diagnostics.

- Samples: 2300 time series segments of 2048 points (0.04 s at the 48 kHz accelerometer sampling frequency).

- Features: mean, skewness, kurtosis, crest factor, (4 numeric features without missing values).

- Task: binary classification (fault or no fault, 90%/10%).

- Transformer Diagnostics dataset [35,36]. It contains power transformers’ oil sampling results.

- Domain: equipment diagnostics.

- Samples: 470 oil sampling results.

- Features: concentrations of gases dissolved in the oil, dibenzyl sulfide concentration (DBDS), breakdown voltage (BV), water capacity (WC) (14 numeric features without missing values).

- Task: Binary classification. The dataset contains a health index (less is better) and we conditionally classify transformers with a value higher than 40 as bad (25%) and the rest as good (75%) [37].

- Pima Indians Diabetes database [38]. It originally was from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

- Domain: medical diagnostics.

- Samples: 768 values of tests and measurements from patients.

- Features: 8 diagnostic features such as pregnancies, OGTT (Oral Glucose Tolerance Test), blood pressure, skin thickness, insulin, BMI (Body Mass Index), age, and pedigree diabetes function.

- Task: binary classification (diabetic or non-diabetic, 35/65%).

4.2. Black-Box Models

Two widely used classifiers served as the underlying models whose predictions we explained:

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoostClassifier).

- Random Forest (RandomForestClassifier).

Hyperparameters were tuned via GridSearchCV (Scikit-learn interface).

4.3. Procedures for Model Training and Generating Explanations

Machine learning models were trained with hyperparameter selection in a cross-validation mode. The training-validation part comprised 80% of each dataset. The scikit-learn library function train_test_split was applied for splitting (random_state = 42, shuffle = True, stratify = stratify_arg).

Tuned hyperparameters for the Random Forest:

- Number of trees: 50, 100, or 200;

- Maximum tree depth: 3, 5, or without limit;

- Minimum samples number of splitting: 3, 4, 5, or 6.

Tuned hyperparameters for the XGBoost:

- Number of trees: 50, 100, or 200;

- Maximum tree’s depth: 3, 5, or without limit;

- Learning rate: 0.01, 0.1, or 0.2.

Tuning of the models was performed on the training-validation part (80%). The process involved generating explanations, such as membership functions. In the end, explanations were generated for the entire test set, which included 20% of each dataset. The result of each method was recorded in the form of a text, as shown below.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

A comprehensive evaluation of explainable AI (XAI) methods must capture both computational performance and human-centric utility. As explanation complexity is of high importance, there are certain approaches to measure it. Namely, it is measured as rule length or number of features that directly affect cognitive load. Shorter anchors or sparse feature sets consistently improve user comprehension and trust [12].

As explanations should be robust to small input data perturbations, consistency (stability) was measured via the average Levenshtein distance.

Finally, purely quantitative assessments cannot determine whether explanations are truly helpful for practical use or not. Thus, our user studies collected subjective metrics.

Based on recent recommendations, we used comprehensive quantitative and qualitative metrics to evaluate and compare explanation methods:

- Execution time: Mean and standard deviation of explanation generation time per instance.

- Complexity: Number of conditions or features explicitly used in generated explanations.

- Coverage:

- AnchorTabular: Proportion of test instances with anchors meeting a precision threshold ≥ 0.95. This is the default threshold for AnchorTabular [39].

- SHAP-Rule: Proportion of instances where fuzzy rule activation strength (α) ≥ 0.33. The thresholds 0.95 and 0.33 were selected empirically to ensure a balance between fidelity and coverage.

- Fidelity: Agreement rate between explanation predictions and the original model:

Equation (17) is based on the number of elements of the test dataset that fit the explanatory rule (total explained instances) and how many of them the model gave the same result as the rule (number of explanation model prediction matches). Only those rules were taken into account, for which the precision threshold ≥ 0.95 or α ≥ 0.33.

- 5.

- Consistency (robustness): In DSS, end-users primarily interacted with explanations presented in a textual form. Therefore, the consistency of explanations should reflect how similarly users perceived explanations for slightly disturbed input data. Comparing explanations at the textual level by means of using Levenshtein distance allows for capture of significant changes that directly affect user perception, not just sets of numerical characteristics. The Levenshtein similarity quantifies how closely the textual explanations match, measuring the cognitive coherence experienced by users.

Algorithm for consistency computation:

- Generate the original explanation text for a given input instance.

- Generate several (10) slightly perturbed input instances. We perturb each test sample by small Gaussian noise (1% of feature standard deviation).

- For each perturbed input, generate its corresponding textual explanation.

- Compute the normalized Levenshtein similarity:

- Average these similarity values for each instance, then average them again across all test instances.

- 6.

- Subjective expert assessment: expert survey conducted by subject area specialists (10 experts per dataset domain). Evaluation criteria: Simplicity and speed of understanding of the explanation. Responses were recorded using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1, simplicity and speed are very low, to 7, simplicity and speed are very high). Experts rated the explanations for each of the three methods in a random order for 10 random examples from the test set (the same examples for each expert).

For each method, the mean, standard deviation, and median rating across all expert-judged instances were computed.

4.5. Implementation Details

Experiments were implemented in Ubuntu. Python v.3.11 on an Intel Xeon 2.3 GHz with 2 vCPUs and 16 GB RAM, utilizing Alibi v.0.9.6 libraries [39] for AnchorTabular; SHAP v.0.47.2 [40] for TreeSHAP; Scikit-learn v.1.6.1 [41] for Random Forest; and XGBoost v.3.0.2 [42] for Extreme Gradient Boosting.

5. Results

5.1. ML Model Tuning

Table 1 and Table 2 show the results of ML training, tuning, and evaluation. Our aim was not to achieve the highest possible accuracy but rather to use widely applied models and their standard tuning approaches. Actually, maximum accuracy was not required for the analysis of model explanation methods. The experiments present datasets with different levels of classification accuracy.

Table 1.

Models’ hyperparameters.

Table 2.

Models’ accuracy on the test parts of datasets.

5.2. Text Formats of Explanations and Their Assessment by Experts

Below are examples of how the explanations of the compared methods looked on the same test instances (K = 4 and T = 0.8 for SHAP-L and SHAP-R). We show the SHAP results only for the first dataset to save space in this paper, since they look similar to those of SHAP-L but contain values for all features.

CWRU bearing:

- SHAP: Skewness is −0.225 (value 0.550) AND Kurtosis is −0.047 (value 0.324) AND Crest is 3.318 (value 0.097) AND Mean is 0.016 (value 0.029): Defect detected.

- SHAP-L: Skewness is −0.225 (value 0.550) AND Kurtosis is −0.047 (value 0.324) (value 0.029): Defect detected.

- AnchorT: Skewness ≤ −0.11 AND Kurtosis ≤ −0.02: Defect detected.

- SHAP-R: Skewness is below average AND Kurtosis is below average: Defect detected.

Transformer diagnostics:

- SHAP-L: Hydrogen is 590 (value 0.245) AND Acethylene is 582 (value 0.216) AND Methane is 949 (value 0.210) AND Ethylene is 828 (value 0.136): State is bad.

- AnchorT: Acethylene > 0.00 AND Methane > 8.00 AND Ethane > 72.00 AND Water_content ≤ 11.00: State is bad.

- SHAP-R: Hydrogen is high AND Acethylene is average AND Methane is high AND Ethylene is high: State is bad.

Pima Indians Diabetes:

- SHAP-L: Glucose is 162 (value −0.582) AND Pregnancies is 10 (value −0.119) AND BMI is 27.70 (value 0.109).

- AnchorT: Glucose > 140.00 AND Pregnancies > 6.00 AND BMI > 27.50: Diabetes.

- SHAP-R: Glucose is above average AND Pregnancies is above average AND BMI is below average.

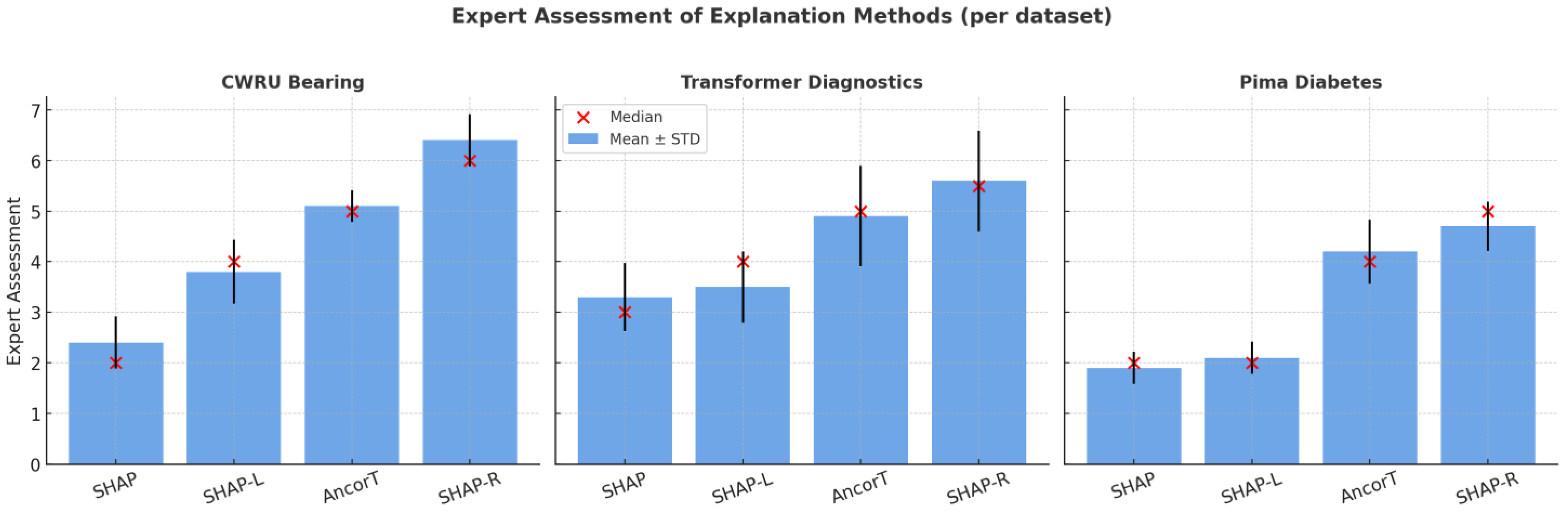

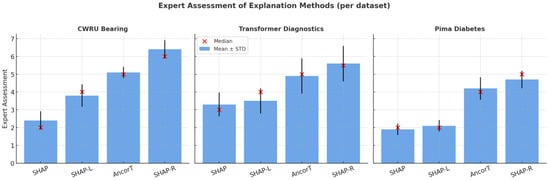

As mentioned above, experts rated each explanation according to simplicity and speed of understanding using a 7-point Likert scale (Table 3). Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests (Table 4) were performed to detect differences across methods for each dataset, followed by pairwise Mann–Whitney tests with Holm correction (Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7). Figure 4 shows a visualization example for the Pima Indians Diabetes dataset. To simplify the experts’ tasks, they were asked to estimate the results of the XGB classifier only.

Table 3.

Assessment of the clarity of explanations by experts.

Table 4.

Kruskal–Wallis tests for expert ratings.

Table 5.

Pairwise Holm-adjusted p-values for CWRU dataset.

Table 6.

Pairwise Holm-adjusted p-values for Transformer Diagnostics dataset.

Table 7.

Pairwise Holm-adjusted p-values for Pima Indians Diabetes dataset.

Figure 4.

Visualization of experts’ assessments.

For all three datasets, the null hypothesis of equality of estimate distributions between the SHAP-Rule and two other SHAP-based methods was rejected at standard significance levels (p < 0.005). At the same time, the difference between SHAP-Rule and AnchorTabular was not statistically significant.

5.3. Comparitive Analysis of Explanation Methods

The results of the metric calculations are presented in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10. Since the AnchorTabular method forms explanations stochastically, it was averaged over 10 runs on the test dataset. The best results (and those close to the best) are bolded.

Table 8.

Method comparison using CWRU Bearing dataset.

Table 9.

Method comparison using Transformer Diagnostics dataset.

Table 10.

Method comparison using Pima Indians Diabetes dataset.

Other widely used XAI methods such as LIME and RuleFit were not included in the quantitative comparison, since their crisp discretization and stochastic sampling introduced additional variability that hindered direct benchmarking with deterministic, rule-formatted outputs. Nevertheless, their theoretical analysis in Section 2 confirms that SHAP-Rule achieves comparable interpretability while substantially improving computational efficiency.

Concerning SHAP and SHAP-L, it is impossible to estimate global accuracy and coverage according to the same principles used in AnchorT and SHAP-R. The main reason for this is that they do not form rules.

Time measurements were made with assumptions, using measurements via the Python core function time.time, so the differences in execution time for SHAP-based methods may be lower than the measurement error. However, it is important that the difference from AnchorTabular is 2–3 orders of magnitude away from SHAP, which is essential for DSS. A difference of tens of milliseconds does not matter for DSS, so we did not conduct a more thorough study of execution time.

5.4. Time Complexity

The increase in time complexity (per instance) of SHAP-Rule was O(F log F), where F is the number of features due to the sorting of SHAP-value features. Extra memory costs for SHAP-Rule were negligible compared to the machine learning model; only seven boundary values for membership functions were required. In the experiments, SHAP-Rule generated one explanation within 1–2 ms per instance on a standard CPU (Intel Xeon 2.3 GHz, 2 vCPUs, 16 GB RAM). This makes SHAP-Rule suitable for real-time deployment in embedded or industrial DSS environments.

6. Discussion

The experimental evaluation provides a balanced assessment of SHAP-Rule against numeric SHAP (TreeSHAP, SHAP-L) and rule-based AnchorTabular across three diagnostic datasets (CWRU Bearing, Transformer Diagnostics, Pima Indians Diabetes). Domain experts consistently preferred rule-formatted explanations over purely numeric vectors, underscoring the practical value of concise linguistic rules in time-sensitive diagnostic settings. Omnibus non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis) confirmed significant differences between methods for all datasets; post hoc analyses with multiplicity control showed that SHAP-Rule was significantly better rated than the numeric baselines (TreeSHAP, SHAP-L), whereas differences between SHAP-Rule and AnchorTabular were not statistically significant after adjustment. Thus, SHAP-Rule matched AnchorTabular in perceived interpretability while clearly surpassing numeric SHAP outputs.

6.1. Interpretability and Communication

SHAP-Rule’s key advantage is its deterministic conversion of numeric SHAP vectors into compact fuzzy IF–THEN clauses expressed in familiar linguistic terms (e.g., “extremely high”, “below average”, etc.). This directly addresses the gap between quantitatively precise but cognitively heavy numeric attributions and the need for rapid, communicable rationales in operations. The resulting rules facilitate quick reading and discussion among stakeholders without sacrificing the formal linkage to feature attributions.

6.2. Coverage–Fidelity Profile

SHAP-Rule retains very high fidelity to the underlying model on the explained subset (often near-perfect) while accepting a small, quantified reduction in coverage relative to AnchorTabular (typically 1–3% absolute; e.g., 0.883 vs. 0.904 on CWRU). Reporting coverage and fidelity together makes the operational trade-off transparent; in practice, the minor coverage gap is offset by SHAP-Rule’s determinism, latency, and ease of communication. Across all three datasets, coverage decreased by 1–3 percentage points compared with AnchorTabular (CWRU: −2.1%, Transformer Diagnostics: −2.1%, Pima Indians Diabetes: −2.9%), while fidelity remained near 1.0. In diagnostic DSS, such a small reduction does not affect decision reliability, since uncovered cases still receive the model’s standard SHAP-based output, ensuring that no instance is left unexplained operationally.

6.3. Robustness and Consistency

Under small Gaussian perturbation of inputs, SHAP-Rule exhibits high textual consistency (often >0.90), though not uniformly across all tasks (e.g., lower values on the CWRU Bearing dataset). This reflects a general tension between strict robustness and rule compactness; we therefore present consistency alongside coverage and fidelity to give a full picture of stability. Handling of missingness (absent in the current datasets) is left for future work via adaptive memberships.

6.4. Computational Efficiency and Complexity

SHAP-Rule generates explanations in milliseconds per instance on standard CPU hardware, while AnchorTabular operates on the order of seconds—an important difference for real-time decision-support. The per-instance time complexity scales as O(F log(F)); memory overhead is negligible (a small set of boundary points for membership functions). In terms of explicit conditions, the complexity of SHAP-Rule explanations is comparable to that of AnchorTabular rather than uniformly lower, which we report to avoid overexaggeration and to reflect the quantitative results.

Given its millisecond-level latency and expert-rated clarity, SHAP-Rule is suitable for real-time diagnostic DSS in energy, healthcare, and industrial maintenance, providing concise rule texts that reduce cognitive load.

6.5. Comparison with LLM-Aided Explanations

LLM-generated rationales can be insufficiently faithful to model evidence, stochastic (prompt-/seed-sensitive), and costly in latency/computation, which complicates deployment in real-time or safety-critical DSS and necessitates rigorous evaluation and governance [7,20,21]; by contrast, SHAP-Rule provides a deterministic, millisecond-latency pathway from numeric attributions to compact fuzzy IF–THEN rules with quantified activation, explicit and auditable linkage to SHAP values, and stability across runs, making it deployment-friendly. Accordingly, we position SHAP-Rule as complementary to LLM pipelines: it supplies structured, low-latency, traceable core explanations, while any LLM component—if used—would act only as a constrained paraphraser grounded in the SHAP-Rule output, without introducing unsupported claims and preserving reproducibility and runtime guarantees.

6.6. Generalization and Limitations

SHAP-Rule is model-agnostic for tabular data and can be extended to higher-dimensional or sparse settings by grouping correlated features and tuning the selection thresholds (K and T) to preserve rule succinctness. For structurally sparse or zero-inflated features, we propose optionally including an explicit “is missing/zero” linguistic term and estimate membership boundaries with robust quantiles; in practice, this stabilizes coverage without increasing rule length. The per-instance complexity remains the same, which keeps latency in the millisecond range even for hundreds of features.

Methodological constraints include reliance on quartile-driven (arcsinh-based) linguistic partitions and triangular memberships (which may oversimplify complex distributions) and dependence on the quality of SHAP attributions from the underlying model. To address these points, future work will include (i) sensitivity analyses over (K, T) and the activation threshold α; (ii) incorporation of grouped/interaction attributions where synergistic effects are expected; (iii) adapting the same linguistic transformation to alternative attribution backends (e.g., LIME and permutation importance); and (iv) larger user studies quantifying decision speed, confidence, error reduction, and trust in operational workflows.

7. Conclusions

We presented SHAP-Rule, a deterministic and computationally efficient framework that converts numeric SHAP attributions into compact fuzzy IF–THEN linguistic rules with quantified activation. Across three diagnostic tasks, SHAP-Rule delivered rule-formatted explanations that were rated as significantly more interpretable than numeric SHAP baselines and comparable to AnchorTabular, while sustaining millisecond-level latency and an order-of-magnitude speed advantage over AnchorTabular (≈1–2 ms vs. ≈0.3–2.3 s across datasets), together with very high fidelity on the explained subset and a small, quantified coverage gap (≈1–3%). The method’s limitations include quartile-driven (arcsinh-based) partitions and triangular memberships that may under-capture multimodality, dependence on the quality of SHAP attributions, and reduced linguistic diversity under extreme sparsity. Although this study focused on tabular diagnostic datasets, the proposed SHAP-Rule framework can be directly extended to other domains with high-dimensional or sparse data by adapting the feature grouping and fuzzy term generation procedures, preserving its interpretability and efficiency.

Novelty of the research:

- A deterministic post hoc pipeline with calibrated rules is proposed. SHAP-Rule automatically converts numeric SHAP attributions into compact fuzzy IF–THEN rules with quantified activation, selecting antecedents by a cumulative threshold, T, with a hard cap, K. The procedure is model-agnostic, auditable, and very fast.

- Linguistic terms are derived directly from data via an arcsinh transform and Tukey fences with redundancy pruning. The same linguistic transformation is drop-in extensible to alternative attribution backends (e.g., LIME and permutation importance) and to grouped/interaction attributions for high-dimensional settings.

- The research introduces a metric suite for complexity, coverage, fidelity, consistency, and statistically validated expert estimations. This suite enables assessing the generated explanation in its native form (such as a user-facing textual message within a decision-support system) rather than only as numeric artifacts.

Future research should clearly focus on extending empirical testing of additional datasets and domains, including scenarios with higher-dimensional feature spaces. It is necessary to continue further improving explanation robustness and practical applicability by adjusting the heuristic parameters of the algorithm, such as the maximum number of features in a rule (K), the required minimum level of the sum of the absolute SHAP values of the selected features (T), and the confidence threshold for the results by level α. Another important task is extending the SHAP-Rule concept to other attribution frameworks, such as LIME or permutation-based importance, by applying the same fuzzy linguistic transformation to their numeric explanations. Additionally, future work will involve large-scale usability studies with domain experts and non-experts to assess practical decision-making performance, cognitive load, and user trust when applying SHAP-Rule explanations. Finally, there is a need to improve evaluation framework by incorporating extensive user studies. These efforts should better quantify the practical impact and usability of generated explanations in real-world settings. We plan to apply the proposed SHAP-Rule approach to classification tasks for power equipment characterized by a large number of diagnostic features, where ensuring both interpretability and robust predictive performance will be of particular importance [43].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization A.I.K. and P.V.M.; methodology, A.I.K. and P.V.M.; validation, P.V.M. and S.A.E.; formal analysis, S.A.E.; investigation, A.I.K.; resources, A.I.K. and S.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.K. and P.V.M.; writing—review and editing, P.V.M.; visualization, A.I.K. and S.A.E.; supervision, A.I.K.; project administration, S.A.E.; funding acquisition A.I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out within a state assignment with the financial support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (subject No. FEUZ-2025-0005, Development of models and methods of explainable artificial intelligence to improve the reliability and safety of the implementation of distributed intelligent systems at power facilities).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available [34,36,39,40,41,42].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why Should I Trust You? Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL), San Diego, CA, USA, 10–15 February 2016; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Z.; Chau, D.H.; Saldana, C. An Interrogative Survey of Explainable AI in Manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2024, 20, 7069–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacao, J.; Santos, J.; Antunes, M. Explainable AI for industrial fault diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 47, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.C.; Susto, G.A.; Brito, J.N.; Duarte, M.A.V. An Explainable Artificial Intelligence Approach for Unsupervised Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zereen, A.N.; Das, A.; Uddin, J. Machine Fault Diagnosis Using Audio Sensors Data and Explainable AI Techniques—LIME and SHAP. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 3463–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X. Enhancing the Interpretability of SHAP Values Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.00079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosiewska, A.; Biecek, P. Do Not Trust Additive Explanations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.11420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhi, S. Fuzzy Inference System with Interpretable Fuzzy Rules: Advancing Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Disease Diagnosis—A Comprehensive Review. Inf. Sci. 2024, 662, 120212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, L.; Cohen, K.; De Baets, B. A Narrative Review on the Interpretability of Fuzzy Rule-Based Models from a Modern Interpretable Machine Learning Perspective. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, V.A. Methodological Aspects on Integrating Fuzzy Systems with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence-Empowered Decision Support Systems; Learning and Analytics in Intelligent Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; p. 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Anchors: High-Precision Model-Agnostic Explanations. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 32, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H.; Popescu, B.E. Predictive Learning via Rule Ensembles. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2008, 2, 916–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letham, B.; Rudin, C.; McCormick, T.H.; Madigan, D. Interpretable Classifiers Using Rules and Bayesian Analysis: Building a Better Stroke Prediction Model. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2015, 9, 1350–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, M.W.; Shavlik, J.W. Extracting Tree-Structured Representations of Trained Networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); MIT Press: Denver, CO, USA, 1996; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Giudici, P. Group Shapley with Robust Significance Testing and Its Application to Bond Recovery Rate Prediction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.03041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullum, M.; Redelmeier, A.; Aas, K. GroupShapley: Efficient Prediction Explanation with Shapley Values for Feature Groups. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.12228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrenin, P.V.; Gamaley, V.V.; Khalyasmaa, A.I.; Stepanova, A.I. Solar Irradiance Forecasting with Natural Language Processing of Cloud Observations and Interpretation of Results with Modified Shapley Additive Explanations. Algorithms 2024, 17, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatset, H.; Shater, A. Beyond Black Box: Enhancing Model Explainability with LLMs and SHAP. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.24650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khediri, A.; Slimi, H.; Yahiaoui, A.; Derdour, M.; Bendjenna, H.; Ghenai, C.E. Enhancing Machine Learning Model Interpretability in Intrusion Detection Systems through SHAP Explanations and LLM-Generated Descriptions. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Pattern Analysis and Intelligent Systems (PAIS), El Oued, Algeria, 24–25 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Huerta, R.; Sotelo, A.; Quintela, A.; Kumar, P. EXPLICATE: Enhancing Phishing Detection through Explainable AI and LLM-Powered Interpretability. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.20796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Deng, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Du, M. Explainability for Large Language Models: A Survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldshmidt, R.; Horoviczm, M. TokenSHAP: Interpreting Large Language Models with Monte Carlo Shapley Value Estimation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.10114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaeipoor, F.; Sabokrou, M.; Fernández, A. Fuzzy Rule-Based Explainer Systems for Deep Neural Networks: From Local Explainability to Global Understanding. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 3069–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczak, A.L.; Baugher, B.D.; Zaback, K. Fuzzy Rules for Explaining Deep Neural Network Decisions (FuzRED). Electronics 2025, 14, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, J.M.; Bonissone, P.P. Critical Thinking about Explainable AI (XAI) for Rule-Based Fuzzy Systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 3579–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaus, M.M.; Dam, T.; Alam, S.; Pham, D.-T. X-Fuzz: An Evolving and Interpretable Neuro-Fuzzy Learner for Data Streams. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 4001–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Doborjeh, M.; Doborjeh, Z. Constrained Neuro Fuzzy Inference Methodology for Explainable Personalised Modelling with Applications on Gene Expression Data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokmen, O.B.; Guven, Y.; Kumbasar, T. FAME: Introducing Fuzzy Additive Models for Explainable AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.07011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacto, M.J.; Alcalá, R.; Herrera, F. Interpretability of Linguistic Fuzzy Rule-Based Systems: An Overview of Interpretability Measures. Inf. Sci. 2002, 181, 4340–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouifak, H.; Idri, A. A comprehensive review of fuzzy logic based interpretability and explainability of machine learning techniques across domains. Neurocomputing 2025, 647, 130602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erson, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. Explainable AI for Trees: From Local Explanations to Global Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.04610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. CWRU Bearing Datasets. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/brjapon/cwru-bearing-datasets (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Velasquez, A.M.R.; Lara, J.V.M. Data for: Root Cause Analysis Improved with Machine Learning for Failure Analysis in Power Transformers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 115, 104684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. Failure Analysis in Power Transformers Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/shashwatwork/failure-analysis-in-power-transformers-dataset (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Khalyasmaa, A.I.; Matrenin, P.V.; Eroshenko, S.A. Assessment of Power Transformer Technical State Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Probl. Reg. Energetics 2024, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. Pima Indians Diabetes Database. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- GitHub. SeldonIO/Alibi. Available online: https://github.com/SeldonIO/alibi (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- GitHub. Shap/Shap. Available online: https://github.com/shap/shap (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- GitHub. Scikit-Learn/Scikit-Learn. Available online: https://github.com/scikit-learn/scikit-learn (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- GitHub. Dmlc/Xgboost. Available online: https://github.com/dmlc/xgboost (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Khalyasmaa, A.I.; Matrenin, P.V.; Eroshenko, S.A.; Manusov, V.Z.; Bramm, A.M.; Romanov, A.M. Data Mining Applied to Decision Support Systems for Power Transformers’ Health Diagnostics. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).