Renewable-Integrated Agent-Based Microgrid Model with Grid-Forming Support for Improved Frequency Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Challenges in the Microgrid System

1.2. Discrete-Event System Specification

1.3. Literature Survey

- Many studies overlook the critical role of the GFM inverter in frequency regulation under high renewable energy penetration.

- Excessive emphasis is often placed on a single control strategy, without fully considering the coexistence of multiple control strategies within the system, resulting in limited validation of the effectiveness of individual or coordinated strategies.

- Model structures are often complex, rigid, and lack formalized representation at the mathematical level. This limits their flexible adaptation to different system configurations and operating scenarios. Additionally, it impairs the models’ readability and interpretability (e.g., the internal logic of the system is difficult to capture and understand, and tracing the causal relationships between inputs and outputs is challenging). Moreover, it also restricts extensibility, hindering the integration of new modules or adjustment of existing ones.

1.4. Motivation and Main Contributions

- By recognizing the critical role of the GFM inverter in frequency stability under high renewable penetration, this study designs and embeds the GFM inverter into specific agent-based models, thereby enabling efficient verification of its effectiveness in frequency regulation within microgrids.

- Multiple frequency regulation strategies—including ESS scheduling, Automatic Generation Control (AGC), and Predictive Automatic Generation Control (PAGC)—are integrated into the model, enabling systematic verification of diverse control strategies within the microgrid framework. Importantly, the framework offers high extensibility, allowing additional control strategies to be incorporated and tested in future applications by simply modifying the corresponding Python files (Python 3.7).

- All system components are modeled based on agents and rely on DEVS to achieve rigorous mathematical formalized representation. DEVS endows the modeling process of each component with mathematical logic and derivation basis, while the modular characteristics of agents ensure the flexibility of the overall model. Specifically, the addition, removal, or reconstruction of components can be realized only by adjusting the mathematical parameters and interaction rules of the corresponding agents, without changing the overall mathematical architecture and logical topology of the model. This further ensures that the model can accurately adapt to power systems of different scales and operating scenarios under strict mathematical constraints.

1.5. Organization of the Paper

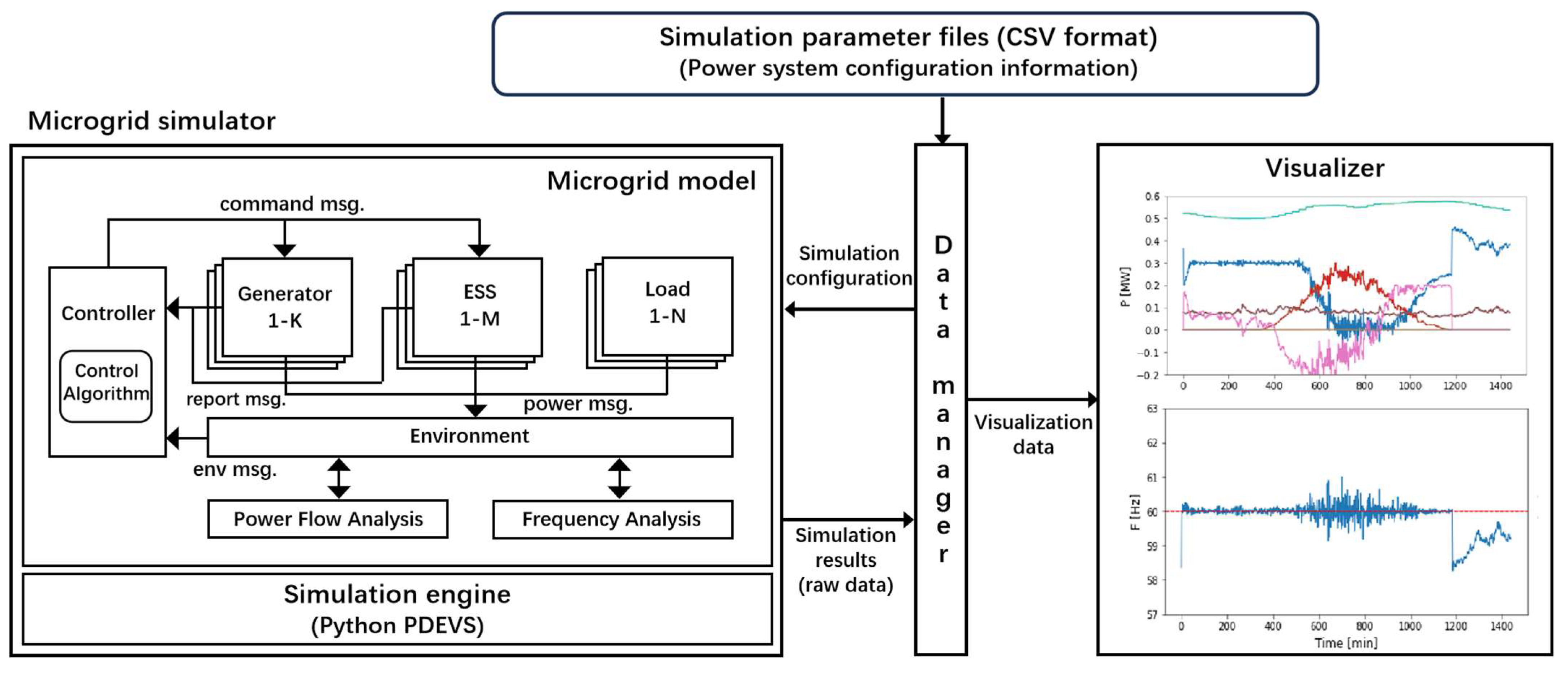

2. Model Design

2.1. System Component Introduction

2.2. Agent-Based Model Design

2.2.1. Environment Model

2.2.2. Controller Model

- Control algorithms

- Economic dispatch solution

- Algorithms execution

2.2.3. Generator Model

2.2.4. ESS Model

2.2.5. Load Model

2.3. Model Implementation

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Experimental Scenarios

3.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

- Maximum frequency

- Minimum frequency

- Peak to peak value

- Maximum frequency deviation rate

- Frequency recovery time

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, R.; Saha, T.K.; Modi, N.; Masood, N.-A.; Mosadeghy, M. The combined effects of high penetration of wind and PV on power system frequency response. Appl. Energy 2015, 145, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J. Agent-based energy management and control of a grid-connected wind/solar hybrid power system. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2008 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Wuhan, China, 17–20 October 2008; pp. 2362–2365. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Zhu, H.; Han, X.; Holburn, D. Dynamic multi-agent-based management and load frequency control of PV/fuel cell/wind turbine/CHP in autonomous microgrid system. Energy 2019, 173, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motewasel, M.; Seifi, A.R. Expert energy management of a micro-grid considering wind energy uncertainty. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 83, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, S.; Döhler, J.S.; Oliveira, J.G.; Boström, C. Grid forming inverters: A review of the state of the art of key elements for microgrid operation. Energies 2022, 15, 5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Review of low inertia in power systems caused by high proportion of renewable energy grid integration. Energies 2023, 16, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, A.; Sen, D.; Bera, A.K.; Ray, D. Microgrid: A review. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference: South Asia Satellite (GHTC-SAS), Trivandrum, India, 23–24 August 2013; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Denholm, P.; Cochran, J.; Brinkman, G.; Jorgenson, J. Inertia and the Power Grid: A Guide Without the Spin; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S.; Saleem, M.I.; Roy, T.K. Impact of high penetration of renewable energy sources on grid frequency behaviour. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 145, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.; Ilic, J. Frequency Instability Problems in North American Interconnections; DOE/NETL-2011/1473; National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL): Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Morgantown, WV, USA; Albany, OR, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 1547-2018 (Revision of IEEE Std 1547-2003); IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–138.

- Serban, I.; Ion, C.P. Microgrid control based on a grid-forming inverter operating as virtual synchronous generator with enhanced dynamic response capability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2017, 89, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler, B.P.; Praehofer, H.; Kim, T.G. Theory of Modeling and Simulation, 2nd ed; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, T.-G.; Choi, S.H. CoDEVS: An extension of DEVS for integration of simulation and machine learning. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2021, 20, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, U.; Hansen, T.M.; Tonkoski, R.; Copp, D.A. Model predictive frequency control of low inertia microgrids. In Proceedings of the IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 2111–2116. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, L.D.; Kimball, J.W. Frequency regulation of a microgrid using solar power. In Proceedings of the IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Fort Worth, TX, USA, 6–10 March 2011; pp. 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Tuffner, F.K.; Schneider, K.P.; Lasseter, R.H.; Xie, J.; Chen, Z.; Bhattarai, B. Modeling of grid-forming and grid-following inverters for dynamic simulation of large-scale distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, V.V.; Roselyn, J.P.; Nithya, C.; Sundaravadivel, P. Development of Grid-Forming and Grid-Following Inverter Control in Microgrid Network Ensuring Grid Stability and Frequency Response. Electronics 2024, 13, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameen, M.; Lu, Z.; El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Younis, W.; Zardari, B.A.; Junejo, A.K. Improving frequency stability in grid-forming inverters with adaptive model predictive control and novel COA-jDE optimized reinforcement learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanashi, H.K.; Mohammadi, F.D.; Verma, V.; Solanki, J.; Solanki, S.K. Hierarchical multi-agent based frequency and voltage control for a microgrid power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 135, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, G.T.; Beza, T.M.; Shahzad, M. Model-based hierarchal control framework for frequency and voltage stability in islanded microgrids with low inertia. APL Energy 2025, 3, 026104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Dhillon, J. PyPSA: Open Source Python Tool for Load Flow Study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1854, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinney, W.F.; Hart, C.E. Power flow solution by Newton’s method. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1967, PAS-86, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durvasulu, V.; Hansen, T.M. Market-based generator cost functions for power system test cases. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2018, 3, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tendeloo, Y. Activity-Aware DEVS simulation. Master’s Thesis, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.P.; Mather, B.A.; Pal, B.C.; Ten, C.-W.; Shirek, G.J.; Zhu, H.; Fuller, J.C.; Pereira, J.L.R.; Ochoa, L.F.; de Araujo, L.R.; et al. Analytic considerations and design basis for the IEEE distribution test feeders. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3181–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Contributions and Limitations | GFM Inverter | Control Strategies | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15,16] | Proposed islanded microgrid frameworks that improve voltage and frequency stability, but did not consider GFM inverters. | Without | Single | Fixed |

| [17,18,19,20] | Verified the advantages of GFM inverters in maintaining voltage and frequency stability but focused mainly on GFM itself while neglecting the role of multiple controls. | With | Single | Fixed |

| [21] | Developed a differential equation-based hierarchical control framework capable of dynamic voltage and frequency control, but with a fixed structure and high complexity, limiting flexibility. | Without | Single | Fixed |

| Component | Function | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Bus | A conductive node connecting lines, generators, and transformers. | Environment model |

| Line | A transmission line connecting two buses. | |

| Transformer | A device that changes voltage levels between buses. | |

| Control system | A system that controls the operation of generators and ESSs to maintain a stable power supply according to load demand. | Control model |

| Load | Devices consuming both active and reactive power. | Load model |

| ESS | Energy storage system. | ESS model |

| Synchronous generator | A generator that induces a three-phase voltage by rotating the rotor. | Generator model |

| Non-synchronous generator (without GFM) | A generator that does not have a rotor and generates alternating current based on an inverter, which includes renewable energy such as solar and wind power. | |

| Non-synchronous generator (with GFM) | A nonsynchronous generator equipped with GFM inverter capability, applicable to renewable energy such as solar and wind power. |

| Message | Contents |

|---|---|

| command msg. | Control command ON/OFF/P_SET, active and reactive power set value |

| power msg. | Active and reactive power |

| report msg. | Active and reactive power (ESS reports both power and capacity) |

| environment msg. | Active and reactive power, frequency, and voltage |

| Parameter | Description | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| T | time required to deliver the environment message to the controller | fixed value |

| End time | microgrid termination time | fixed value |

| Parameter | Description | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Control algorithm | An algorithm that distributes active power load among synchronous generators, considering refined dispatch based on the usage of ESS, AGC, and PAGC. | For AGC: distributes based on current active power required by synchronous generators. For PAGC: distributes based on projected active power required after PAGC interval time. |

| AGC | Controls the no-load frequency of synchronous generators to restore system frequency when deviations exceed threshold values. | Applied when system frequency deviation exceeds 0.05 Hz. |

| PAGC | Proactively controls the no-load frequency of synchronous generators by predicting future demand to minimize frequency fluctuations. | Applied every 5 min. |

| Economic Dispatch Solution Algorithm (Solved ED) | Optimization algorithm for efficient active power allocation among synchronous generators. | Incorporates generator cost functions into equations, solves the equations, and allocates active power based on solutions. |

| Parameter | Description | Example Setting |

|---|---|---|

| p_nom | Rated active power, used as an upper bound in case of sudden change. | 0.3 MW |

| p_set_min | Minimum active power, used as the lower limit under steady-state frequency during generation reduction. | 0.01 MW |

| p_set | Active power target, which represents the generation target under nominal frequency; for synchronous generators, the actual output may differ due to frequency changes. | 0.2 MW |

| q_set | Reactive power target, which represents the generation target under nominal frequency; for synchronous generators, the actual output may vary depending on frequency deviations. | 0 var |

| zero_load_cost | No-load generation cost, which represents the generation cost when output is zero. | 191.48949 KRW/T |

| C1 | Quadratic coefficient, which is the coefficient of p2 in the cost function (y = C1 × p2 + C2 × p + zero_load_cost). | 1418.44067 |

| C2 | Linear coefficient, which is the coefficient of p in the cost function (y = C1×p2 + C2 × p + zero_load_cost). | 1063.8305 |

| Parameter | Description | Example Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Generator name, which cannot be set as a number only. | MT |

| Bus | Bus name, which must match a name listed in the bus parameter file. | bus_632 |

| bSync | Synchronous flag, which indicates whether the generator is a synchronous machine involved in frequency regulation (T or F). | T |

| bOn | Initial status, which indicates whether the generator is turned on at the start of the simulation (T or F). | T |

| Control | Control mode, which specifies the generator control type: PV or PQ for synchronous generators, PQ for nonsynchronous generators, and slack for the slack bus generator. | PV |

| data_file | Input file, which contains time-series generation data for the generator. | ./param/solar.csv |

| p_set_change_rate | Ramp rate, which defines how rapidly the target active power is adjusted in response to AGC or PAGC commands, | 0.02 MW/min |

| R | Control coefficient, which defines the sensitivity of a synchronous generator’s active power output to changes in system frequency. | 0.05 |

| bGFM | GFM flag, which indicates whether the generator is of GFM inverter type (T or F). | T |

| price_file | Price file, which contains time-varying generation cost data; if this file is provided, the values of zero_load_cost, C1, and C2 will be ignored. | ./param/SMP.csv |

| Parameter | Description | Example Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Name | ESS name, which cannot be set as a number only. | ESS |

| Bus | Bus name, which must match a name listed in the bus parameter file. | bus_671 |

| Capacity | Energy capacity, which defines the total energy storage capacity of ESS. | 2 MWh |

| maxPower | Maximum power, which indicates the maximum charging or discharging power of ESS. | 0.2 MW |

| minSOC | Minimum state of charge, which sets the lower SOC limit during operation (based on capacity). | 20% |

| maxSOC | Maximum state of charge, which sets the upper SOC limit during operation (based on capacity). | 90% |

| initSOC | Initial state of charge, which sets the initial SOC at the beginning of simulation (based on capacity). | 70% |

| Charging | Charging efficiency, which determines the efficiency of energy stored during charging. | 95% |

| Discharging | Discharging efficiency, which determines the efficiency of energy released during discharging. | 90% |

| Parameter | Description | Example Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Load name, which cannot consist only of numbers. | Load1 |

| Bus | Bus name, which must match a name listed in the bus parameter file. | bus_646 |

| p_set | Active power, which represents the target active power consumption of the load. | 0.065 MW |

| q_set | Reactive power, which represent the target reactive power consumption of the load. | 0.037 MVAr |

| data_file | Input file, which contains time-series generation data for the load. | ./param/demand.csv |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Load 1 | 0.869 |

| Load 2 | 0.853 |

| Load 3 | 0.864 |

| Load 4 | 0.867 |

| Load 5 | 0.905 |

| Load 6 | 0.878 |

| Load 7 | 0.884 |

| Load 8 | 0.917 |

| Load 9 | 0.830 |

| Parameter | Contents | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Sim_end | Total simulation time. | 1440 min |

| T | Simulation interval time step. | 1 min |

| Set_frequency | System reference frequency. | 60 Hz |

| AGCFrequency | applied when system frequency deviated from the value beyond the limit. | 0.05 Hz |

| PAGCInterval | future power demand is forecasted to pre-adjust synchronous generator output for frequency stability. | 5 min |

| Name | Nominal Power [MW] | Min Set Value [MW] | Max Set Value [MW] | Control Type | Set Value Change Rage [MW/min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.2 | PV | 0.02 |

| G0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Slack | - |

| Number | Scenario | Viewpoint |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | with/without ESS | To verify the flexibility in system configuration |

| 2 | with/without sudden load change | To test the effectiveness of control strategies |

| 3 | with/without GFM | To verify the effectiveness of GFM inverter |

| Evaluation Metric | 1-1 | 1-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum frequency [Hz] | 61.00 | 62.14 |

| Minimum frequency [Hz] | 58.26 | 58.35 |

| Peak-to-peak value [Hz] | 2.74 | 3.79 |

| Maximum frequency deviation rate [%] | 2.90 | 3.57 |

| Frequency recovery time [min] | 1.58 | 10.63 |

| Evaluation Metric | 2-1 | 2-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum frequency [Hz] | 62.14 | 61.00 |

| Minimum frequency [Hz] | 57.74 | 58.26 |

| Peak-to-peak value [Hz] | 4.40 | 2.74 |

| Maximum frequency deviation rate [%] | 3.77 | 2.90 |

| Frequency recovery time [min] | 1.73 | 1.58 |

| Evaluation Metric | 3-1 | 3-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum frequency [Hz] | 61.42 | 62.14 |

| Minimum frequency [Hz] | 58.35 | 58.35 |

| Peak-to-peak value [Hz] | 3.07 | 3.79 |

| Maximum frequency deviation rate [%] | 2.75 | 3.57 |

| Frequency recovery time [min] | 8.05 | 10.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, D.; Lee, S.; Choi, S. Renewable-Integrated Agent-Based Microgrid Model with Grid-Forming Support for Improved Frequency Regulation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193142

Peng D, Lee S, Choi S. Renewable-Integrated Agent-Based Microgrid Model with Grid-Forming Support for Improved Frequency Regulation. Mathematics. 2025; 13(19):3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193142

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Danyao, Sangyub Lee, and Seonhan Choi. 2025. "Renewable-Integrated Agent-Based Microgrid Model with Grid-Forming Support for Improved Frequency Regulation" Mathematics 13, no. 19: 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193142

APA StylePeng, D., Lee, S., & Choi, S. (2025). Renewable-Integrated Agent-Based Microgrid Model with Grid-Forming Support for Improved Frequency Regulation. Mathematics, 13(19), 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13193142