Abstract

It is challenging to recover a real sparse signal using one-bit compressive sensing. Existing methods work well when there is no noise (sign flips) in the measurements or the noise level or a priori information about signal sparsity is known. However, the noise level and a priori information about signal sparsity are not always known in practice. In this paper, we propose a robust model with a non-smooth and non-convex objective function. In this model, the noise factor is considered without knowing the noise level or a priori information about the signal sparsity. We develop an alternating proximal algorithm and prove that the sequence generated from the algorithm converges to a local minimizer of the model. Our algrithm possesses high time efficiency and recovery accuracy. It performs better than other algorithms tested in our experiments when the the noise level and the sparsity of the signal is known.

Keywords:

one-bit compressive sensing; sparse signal reconstruction; alternating proximal algorithm; local convergence MSC:

49M37; 65K10; 65K15; 90C90

1. Introduction

One-bit compressive sensing (CS) was originally introduced in [1]. It has been applied extensively, such as in [2,3,4,5]. Let x be a sparse signal in and B be an matrix. The measurement vector of the signal x is calculated via

where operates componentwise with if and otherwise. The measurement operator is called the one-bit scalar quantizer. The prime target of one-bit CS is to recover the sparse signal x from the one-bit observation b and the measurement matrix B. We will now review existing models for the one-bit CS problem. The ideal optimization model is the following -norm minimization:

where is the -norm of x, counting the number of its non-zero entries. The NP-hardness of model (2) makes approximation challenging. The earliest attempt can be traced back to [1], in which the ideal model (2) was relaxed by

where Y is a diagonal matrix with diagonal entries from b, and is the sum of the absolute values of the components of x. This model is valid for the noiseless case. For the case in which the measurement is contaminated by noise (sign flips), instead of solving model (3), ref. [1] relaxed it as follows:

where is a parameter, and represents the operator projected onto the convex set . Since both models (3) and (4) minimize convex objective functions over the non-convex unit sphere, to overcome difficulties resulting from non-convexity, the following model was proposed in [6]:

where r is an arbitrary positive number. Obviously, the set determined by the two constraints is convex. In addition, the model can be efficiently solved using a linear programming method. However, it was shown numerically that solutions of model (5) are not sparse enough when the signal is known to have s-sparsity, that is, A newer model for the one-bit CS model,

was proposed in [7], where function h is either or . An algorithm called binary iterative hard thresholding (BIHT) was developed for solving model (6). Based on BIHT, the adaptive outlier pursuit (AOP) technique was introduced in [8] for solving the following one-bit CS model:

where L is the noise level, that is, there are at most L measurements in y that are wrongly detected (with sign flips), and is an diagonal matrix whose diagonal entries are either 1 or 0. If , then the ith component of y is correct; otherwise, it is incorrect. If the matrix is specified, model (7) can be reduced to model (6) by disregarding the incorrect measurements. However, in model (7), the noise level L must be given in advance, a condition that is hardly ever satisfied in practice. The following one-sided (OSL0) model was proposed in [9] for when L is unavailable:

where , , and are positive parameters, and e denotes the vector in with all components equal to one. In [9], a fixed-point proximity algorithm was proposed for solving model (8). It was shown that the sequence generated from the fixed-point proximity algorithm converges to a local minimizer of the objective function of model (8) and converges to a global minimizer of the function as long as the initial estimate is sufficiently close to any global minimizer of the function. In [10], the authors took advantage of -regularized least squares to address the one-bit CS problem regardless of the sign information of , namely,

where is a given positive parameter. A primal dual active set algorithm was proposed to solve model (9) and proved to converge within one step under two assumptions: the submatrix of B indexed on the nonzero components of the sparse solution is full row rank and the initial point is sufficiently close to the sparse solution. Therefore, the generated sequence again has a local convergence property. To eliminate the assumptions on data B for better convergence results, xiu et al. [11] proposed the following double-sparsity constrained model:

where , is a penalty parameter and and are two positive integers representing prior information about the upper bounds of the signal sparsity and the number of sign flips, respectively. An algorithm called Gradient projection subspace pursuit was proposed in [11] to solve model (10).

To solve the previous model, either a priori knowledge is required or the algorithm lacks convergence analysis, excluding it from many potential applications. In this study, we introduce a model for the noisy one-bit CS problem that requires neither a priori knowledge of the signal sparsity nor a priori knowledge of the noise level of the measurements. We develop an algorithm to solve the proposed model and analyze the convergence of the proposed algorithm. Our algorithm possesses high time efficiency and recovery accuracy. Moreover, it performs better than other existing algorithms when the the noise level and the sparsity of the signal is known. To summarize, our algorithm is suitable for more many practical scenarios.

2. Elementary Facts

The Euclidean scalar product of and its corresponding norm are denoted by , and , respectively. For a symmetric matrix A, the maximum eigenvalue is denoted by . The M-norm of the vector x is denoted by if the matrix M is positive definite.

Definition 1

(Rockafellar and Wets [12]). Let be a proper lower semicontinuous function.

- (i)

- The domain of f is defined and denoted by ;

- (ii)

- For each , the Fréchet subdifferential of f at x, written , is the set of vectors that satisfiesIf , then ;

- (iii)

- The limiting-subdifferential (Mordukhovich [13]), or simply the subdifferential for short, of f at , written , is defined as follows:

A necessary (but insufficient) condition for to be a minimizer of a proper lower semicontinuous function f is . For a proper lower semi-continuous function , the proximity operator of f is defined by [14]

Clearly, for any , by the calculus of the limiting-subdifferential, we have that .

3. The Model

A classical approach to problem (1) is the least squares (LS) approach [15], in which the estimator is chosen to minimize the data error:

Notice that the LS solution may have a huge norm and is thus meaningless. Regularization methods are needed to stabilize the solution. The basic concept of regularization is to replace the original problem with a “nearby” problem whose solution approximates the required solution. A popular regularization technique is Tikhonov regularization [16], in which a quadratic penalty is added to the objective function:

The second term in the above minimization problem is a regularization term that controls the norm of the solution. Since x is a sparse signal, regularization (see, e.g., [17,18]) can be used to induce sparsity in the optimal solution:

Notice that for any and , the following identity holds:

It follows from [9] (Proposition 3.1) that the function can be majorized by a lower semi-continuous function . We therefore substitute expression in model (16) by the lower semi-continuous function . For notational simplicity, we set and for a fixed . As a consequence, model (16) can be recast as

where . The objective function of model (18) is lower semi-continuous and coercive; therefore, model (18) attains its minimum. By introducing an additional variable , we can rewrite problem (18) as

Furthermore, model (19) can be approximated by the following unconstrained optimization problem (see, e.g., [19], model (2)):

where is a positive relaxation parameter. model (20) has more than one local minimizer. We are now ready to estimate an upper bound of the number of local minimizers of model (20).

Proposition 1.

The number of local minimizers for model (20) is no more than .

Proof.

Let be a local minimizer of model (20). Then, there is a positive number such that

holds for all satisfying . For the vector , we define . In association with this set, we further define

which is a convex set in . Obviously, we have and for all Hence,

holds for all u satisfying . That is, the function attains its local minimum at the vector . Since the function is a strictly convex function on , it actually attains its global minimum at the vector . Notice that the number of all possible sets is . Therefore, there are a total functions of the form , each of which has at most one minimizer. As a result, the number of local minimizers for model (20) is no more than . □

4. Alternating Proximal Algorithm

In this section, we describe an alternating minimization algorithm (see [19,20,21,22]) for finding local minimizers of the objective function of model (20). The alternating discrete dynamical system to be studied is of the following form:

where and are entirely positive definite operators. Next, we address the computation of and . To update more easily, we take with . Then, the x-subproblem can be solved by

where the operator with at is defined by

We take with . Then, the y-subproblem can be solved by

The proximity operator with at can be presented as follows [9] (Proposition 7.2):

Thus, a complete algorithm for solving model (20) can be presented as follows:

Next, we establish the convergence results of the sequence generated by Algorithm 1, where denotes all natural numbers. We use to denote the set of limit points of the sequence and to denote the set of critical points of the function L.

| Algorithm 1 Alternating proximal algorithm (APA) for model (20). |

|

Proposition 2.

Let the sequence be generated by Algorithm 1. Then, the following hold:

- (i)

- The sequence is nonincreasing and convergent;

- (ii)

- The sequence is bounded and

- (iii)

- For all , definewe then have

- (iv)

- is a nonempty compact connected set and ;

- (v)

- L is finite and constant on , equal to .

Proof.

(i) It follows from (25), (27), and the definition of that

which implies that

Since and are positive definite, the sequence does not increase. Since , the sequence is convergent.

(ii) Since the function is coercive, proper lower semi-continuous, and bounded below, the sequence is bounded. In addition, we have from inequality (33) and the convergence of .

(iii) By the very definition of and , we have that for all ,

Because of the definition of , we have

Hence, we can obtain from (34) and (35) that

This yields with [19] (Proposition 2.1). Furthermore, it follows from (29) that .

(iv) It follows from (ii) and the results of point set topology that is nonempty compact connected. Let be a point in , where there exists a subsequence of converging to . Furthermore, by the definition of , we have for all and ,

It follows from (29) that by replacing k with in (37) and letting , we can deduce

In particular, for , we have that . Since the function is lower semicontinuous, we have . There is no loss of generality in assuming that the whole sequence converges to , i.e.,

Notice that the function is continuous, so we have

Thus, . It follows from (31) that and . Owing to the closedness of , we determine that . Hence, .

(v) Let be a point in so that there is a subsequence of , with . Since the sequence is convergent, we have independent of , i.e., L is finite and constant on . □

The next result shows that the sequence generated by Algorithm 1 converges to a local minimizer of (20).

Theorem 1.

The sequence generated by Algorithm 1, with the initial point , converges to a local minimizer of (20).

Proof.

Let be a point in . Then, there exists a subsequence of converging to , and (39) holds. Define

For all satisfying , we deduce that the entries of both y and are all less than on the index set and are all greater than on the index set . Hence, by the definition of , we have

On one hand, there at least exists one index such that . Then, . Thus, we have

Further, we denote the function by . Since is continuous, there is a constant such that

holds for all satisfying . Choose . It follows from (44) and (43) that for all satisfying , there exists at least one index such that , and we have .

On the other hand, for all satisfying and , we have

By the definition of , we get

which, together with (29) and (39), implies that

Thus, we have that

For any , define , then and . We denote the function by . Then, is a convex function and

Hence, we have

which can be reduced to

By letting , it yields that

Furthermore, by the definition of , we have

It follows from (29) and the continuity of the operator that

which is equivalent to

Hence, we obtain

It follows from (52) that

which, together with (56), implies that

We use to denote the function . Then is a convex function. For any , define . Then, and . It follows from (58) that

which can be reduced to

i.e.,

By letting , we can obtain

It follows from (45) and (62) that we have for all and . Thus, is a local minimizer of (20). By Proposition 1 and (iv) of Proposition 2, we have that the sequence converges to a local minimizer of (20). □

Remark 1.

It follows from the proof of Theorem 1 that if , then we have . At this point, we have that is also a local minimizer of (19).

The next theorem shows that if the initial point of Algorithm 1 is sufficiently close to any one of the global minimizers of the function L given in (20), then the sequence generated by Algorithm 1 converges to a global minimizer of model (20).

Theorem 2.

Proof.

We know from Proposition 1 that model (20) has a finite number of local minimizers. If the function has a unique local minimal value, then by Theorem 1, we have that the sequence converges to a global minimizer of (20). Otherwise, we suppose that has at least two local minimal values, and we denote the second smallest minimal value by M. Then, we have that . Since the function is continuous, we can determine that if is sufficiently close to . It follows from (42) that if with , we have . By (i) of Proposition 2, it holds that for all k. By Theorem 1, we know that the sequence converges to which is a local minimizer of . By the lower semi-continuity of , we get . This implies that must be a global minimizer of (20). This completes the proof of the desired result. □

5. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we describe simulation experiments conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed Algorithm 1. Our code was written in Matlab 2015b and executed on a Dell personal computer with 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1135G7 @ 2.40 GHz 2.42 GHz and 16 G memory.

We generated an matrix B whose entries were subjected to the independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) standard Gaussian distribution. We then generated an s-sparse vector , whose nonzero components were drawn from the i.i.d. samples of the standard Gaussian distribution. To avoid tiny nonzero entries of , we let for nonzero and then normalized the resulting vector to be a unit vector. The ideal one-bit measurement vector is given by . To simulate sign flips in actual one-bit measurements, we randomly selected components in and flipped their signs, denoting the resulting vector b. And denotes the flipping ratio in the measurement.

Three metrics were chosen to evaluate the quality of the signals reconstructed by one-bit compressive algorithms. They are the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), Hamming error (HE), and Hamming distance (HD), defined, respectively, by

where is the reconstructed signal with norm 1. The higher the SNR value, the better the reconstructed signal. The values of HE and HD are within the range [0, 1]. The smaller these values, the better the reconstructed signal.

The larger parameter in model (20) is set, the closer model (20) will be to model (19). Hence, in subsequent numerical experiments, we initially set in Algorithm 1, doubled it in every ten iterations, and fixed it when the total number of iterations exceeds 60. This is the same approach described in [9]. For other parameters, we chose , , , , , and . We set the initial estimates and .

First, we explored the performance ofAlgorithm 1 without the noise level or a priori information about signal sparsity. We tried problems of sizes , and 5000. For each n, we generated 100 input vectors and reported the average results over 100 runs in Table 1. We defined , with . In all tests, if or , the Algorithm 1 terminated and outputted , where the operator with at is defined by

The parameter r is set to if ; otherwise, .

Table 1.

Numerical results of Algorithm 1.

From Table 1, we can see that Algorithm 1 can effectively recover the sparse signal x from the one-bit observation b if the flipping ratio .

Second, we assumed that the sparsity s was known and compared the performance of the Algorithm 1 (APA) with two state-of-the-art algorithms, namely, OSL0 in [9] and AOP in [8]. In our experiments, the parameters for OSL0, AOP, and their variants were determined as suggested in [8,9]. All methods start with the same initial points and . In Algorithm 1, we projected x onto set every 25 iterations and outputted .

Three configurations were considered to test the robustness of Algorithm 1 for the one-bit compressive sensing problem. They were designed to test cases of different levels of noise in the measurements, the size of the sensing matrix B, and the true sparsity s of the vector . In the first configuration, we fixed and sparsity at and varied the noise level . In the second configuration, we fixed , sparsity at , and the noise level at and varied m such that the ratio was in . In the third configuration, we fixed and the noise level at and changed the sparsity .

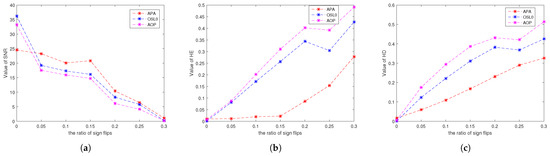

For the first configuration, the average values of SNR, HE, and HD over 50 trials for the signals reconstructed by all algorithms against the noise levels are depicted in Figure 1a, Figure 1b, and Figure 1c, respectively. We can observe from Figure 1 that Algorithm 1 performs better than the other algorithms when the noise level is greater than .

Figure 1.

Average values of (a) SNR, (b) HE, and (c) HD over 50 trials vs. the noise level for all tested algorithms. We fixed and sparsity at 10.

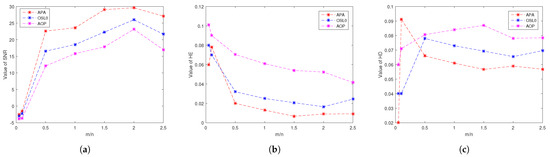

For the second configuration, the average values of SNR, HE, and HD over 50 trials for the signals reconstructed by all algorithms against the ratio of are depicted in Figure 2a, Figure 2b, and Figure 2c, respectively. We can see that Algorithm 1 performs better than the other algorithms when the ratio of is greater than .

Figure 2.

Average values of (a) SNR, (b) HE, and (c) HD over 50 trials vs. for all tested algorithms. We fix , the noise level at , and sparsity at 10.

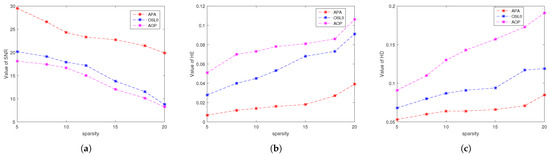

For the third configuration, the average values of SNR, HE, and HD over 50 trials for the signals reconstructed by all algorithms against the sparsity of the ideal signals are depicted in Figure 3a, Figure 3b, and Figure 3c, respectively. We can see that Algorithm 1 performs best among all the algorithms tested in our experiments.

Figure 3.

Average values of (a) SNR, (b) HE, and (c) HD over 50 trials vs. true sparsity s for all tested algorithms. We fix and the noise level at .

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a robust model for the one-bit CS problem and prove that the model has a finite number of local minimizers. We propose an alternating proximal algorithm for solving the proposed model and prove the following: the sequence of the objective function decreases and converges, the set of limit points of the sequence generated from the algorithm is included in the set of critical points of the objective function, the sequence generated from the algorithm converges to a local minimizer of the objective function of the proposed model, and the sequence generated from the algorithm converges to a global minimizer of the function as long as the initial estimate is sufficiently close to any global minimizer of the function. The proposed algorithm is suitable for practical scenarios in which neither the noise level nor the sparsity of the signal are known in advance. Our algorithm possesses high time efficiency and recovery accuracy. Moreover, it performs better than other algorithms tested in our experiments when the the noise level and the sparsity of the signal is known.

Author Contributions

J.-J.W. is responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, software, visualization, and writing—orinitial draft. Y.-H.H. is responsible for conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, validation, writing—original draft and writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Sciences Grant (No. 11871182) and the program for scientific research start-up funds of Guangdong Ocean University (060302102004 and 060302102005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Boufounos, P.T.; Baraniuk, R.G. 1-bit Compressive Sensing. In Proceedings of the Conference on Information Science and Systems (CISS), Princeton, NJ, USA, 19 March 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Guo, D.; Honig, M.L. Sparse channel estimation for massive MIMO with 1-bit feedback per dimension. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), San Francisico, CA, USA, 19–22 March 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wu, J.Y. Amplitude-aided 1-bit compressive sensing over noisy wireless sensor networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2015, 4, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, N.; Yang, L.; Zhang, J. Sub-nyquist 1-bit sampling system for sparse multiband signals. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Lisbon, Portugal, 1–5 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J. A survey on one-bit compressed sensing: Theory and applications. Front. Comput. Sci. 2018, 12, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan, Y.; Vershynin, R. One-bit compressed sensing by linear programming. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2013, 66, 1275–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, L.; Laska, J.; Boufounos, P.T.; Baraniuk, R.G. Roubust 1-bit compressive sensing via binary stable embeddings of sparse vectors. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2013, 59, 2082–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Yang, Y.; Osher, S. Robust 1-bit compressive sensing using adaptive outlier pursuit. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 2012, 60, 3868–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.Q.; Shen, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, N. Noisy 1-bit compressive sensing: Models and algorithms. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2016, 40, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jiao, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhu, L. Robust decoding from 1-bit compressive sampling with ordinary and regularized least squares. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 40, 2062–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Luo, Z.; Xiu, N.; Li, G.Y. Computing one-bit compressive sensing via double-sparsity constrained optimization. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 2022, 70, 1593–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Wets, R. Variational Analysis, Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998; Volume 317. [Google Scholar]

- Mordukhovich, B. Variational Analysis and Generalized Differentiation. I. Basic Theory; Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; Volume 330. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.L.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces; AMS Books in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Björck, A. Numerical Methods for Least Squares Problems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov, A.N.; Arsenin, V.Y. Solution of Ill-Posed Problems; V. H. Winston: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Daubechies, I.; Defrise, M.; Mol, C.D. An iterative thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems with a sparsity constraint. Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 2004, 57, 1413–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.A.T.; Nowak, R.D.; Wright, S.J. Gradient projection for sparse reconstruction: Application to compressed sensing and other inverse problems. IEEE J.-STSP. 2007, 1, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Bolte, J.; Redont, P.; Soubeyran, A. Proximal alternating minimization and projection methods for nonconvex problems: An approach based on the Kurdyka-Łojasiewicz inequality. Math. Oper. Res. 2010, 35, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Soubeyran, A. Inertia and reactivity in decision making as cognitive variational inequalities. J. Convex. Anal. 2006, 13, 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Attouch, H.; Redont, P.; Soubeyran, A. A new class of alternating proximal minimization algorithms with costs to move. SIAM J. Optimiz. 2007, 18, 1061–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Bolte, J.; Redont, P.; Soubeyran, A. Alternating proximal algorithms for weakly coupled convex minimization problems. Applications to dynamical games and PDE’s. J. Convex. Anal. 2008, 15, 485–506. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).