Abstract

In optics, light rays emitted from a light source form a wavefront (orthotomic) upon reflection by a mirror. The mirror is referred to as an antiorthotomic of the orthotomic. The investigation of the relationship between orthotomics and antiorthotomics constitutes an interesting problem in physics. However, the study becomes ambiguous when the orthotomic exhibits singular points. In this paper, we define generalized antiorthotomics of (n, m)-cusp curves in the Euclidean plane by using the singular curve theory. We demonstrate that the singular points of the generalized antiorthotomic sweep out the evolute of the (n, m)-cusp curve. We also investigate the behavior and singular characteristics of the antiorthotomic of the (n, m)-cusp curve. Moreover, we define parallels for (n, m)-cusp curves and reveal the relationship between parallels and generalized antiorthotomics. Finally, repeated antiorthotomics are studied, which is useful for identifying the characteristics of (n, m)-cusp curves.

MSC:

53A04; 57R45

1. Introduction

The study of special submanifolds has garnered significant attention from mathematicians and physicists. For instance, wavefronts, particularly in optics, are instrumental in physics research and can be represented as involutes of caustics (see [1,2,3,4,5]). B. Gu and Y. Zhang developed a wavefront reconstructor using a damped transpose matrix of the influence function. This development offered a valuable tool for testing, evaluating, and optimizing adaptive optics systems (see [6]). In [7], S. Sorgato et al. proposed a wavefront-matching procedure, which enables the design of optics with prescribed intensity for non-symmetric configurations in 3D. Y. Nishizaki et al. presented a new class of deep learning wavefront sensor which could simplify both the optical hardware and image processing in wavefront sensing (see [8]). In [9], J. Kung and E. Manche investigated the effects of wavefront-guided and wavefront-optimized technology on the subjective quality of vision using different laser platforms. In this paper, we concentrate on wavefronts in a classical optical system, where reflection occurs when a light source illuminates a mirror. In accordance with [10,11,12,13], a concise description of the optical system is provided as follows (see Figure 1). Consider a mirror M as an -dimensional submanifold embedded in n-dimensional Euclidean space , with F representing a light source in . In this context, there exists an -dimensional submanifold where its normal lines align with the ray lines generated from F upon reflection on M. W is called a wavefront. In geometrical optics, W is also referred to as an orthotomic of M with respect to and conversely, M is called an antiorthotomic of W with respect to F. In the study of geometric optics and differential geometry, orthotomic and antiorthotomic curves are classically related as reflection counterparts with respect to a fixed point or line. While the orthotomic of a curve corresponds to the reflected rays, the antiorthotomic captures the inverse reflection geometry. These constructions are closely connected to the notions of secondary caustics and isotels in caustic theory, where secondary caustics refer to the orthogonal trajectory of reflected rays, and isotels describe loci of equal optical path length.

Figure 1.

Orthotomic and antiorthotomic.

The study of the orthotomic was initially explored in [14]. J. Xiong introduced the concepts of spherical orthotomic and spherical antiorthotomic, along with determining their local diffeomorphic types in [15]. In geometrical optics, a fundamental problem involves determining the orthotomic through a mirror (antiorthotomic) and a light source. In [16], N. Alamo and C. Criado addressed the inverse problem by proposing a method to construct a family of mirrors, denoted as , parameterized by a real number . These mirrors can generate reflected rays normal to W from the light source F. is called a generalized antiorthotomic or a-antiorthotomic of W relative to Actually, the construction of involves taking the envelopes of ellipsoids or hyperboloids, both sharing the foci F and a point varying on W. The distance between the two vertices is equal to . Notably, when the ellipsoids or hyperboloids degenerate into hyperplanes that are parallel to the tangent hyperplanes of In this case, the generalized antiorthotomic essentially reduces to the antiorthotomic M.

While regular curves and their antiorthotomics have been studied, the investigation of the antiorthotomics of singular curves is equally crucial. Singular curves are significant as they are prevalent in practical scenarios and represent a generalization of regular curves. In [17], T. Fukui delved into the local differential geometry of singular curves with finite multiplicities. In [18], C. Zhang and D. Pei analyzed the behavior and the singular property of the evolute of an -cusp curve which may have singular points. Furthermore, they established a one-to-one correspondence between the orthotomics and the caustics of -cusp curves in [19]. Then D. Pei et al. investigated generalized Bertrand curves and nullcone fronts of framed curves in Lorentz–Minkowski 3-space in [20,21]. As the orthotomics we studied here are singular curves, their antiorthotomics will inevitably exhibit singular points. One of the main motives of our study is to investigate the geometric properties of the antiorthotomic near singular points. This is also a part of our research projects about the classification and characterization of singularities for curves and surfaces ([22,23,24]).

We consider the orthotomic as an -cusp curve instead of a regular curve, and construct the a-antiorthotomic from the -cusp curve and a light source point F. Let be an -cusp curve and F the origin of . Suppose and is the ellipse or hyperbola which has the foci F and a point on One of the directrices closest to F is denoted as Based on fundamental knowledge of conic curves, as detailed in [25], represents the locus of the point such that the ratio of the distance from p to F and the distance from p to d is a constant, denoted as the eccentricity e. For any the value of e is . represents an ellipse or a hyperbola depending on the eccentricity or , respectively. When or becomes either a straight line passing through F and or a circle centered at F, respectively. It forms a family of conic curves as varies in I. The envelope of the family of conic curves is defined as the a-antiorthotomic of relative to F (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A cusp orthotomic , an ellipse and an a-antiorthotomic .

In order to study , we give the equation of . Let Q be the intersection point of the directrix d and the straight line passing through F and , then the distance between Q and the center of is Thus, we have

Since , the equation for Q can be rewritten as follows:

For any we have It follows that

Notably, when acts as a perpendicular bisector of the line segment with endpoints F and .

Thus, for any a family of curves is defined using the map where so that for any fixed the zero set of the map given by is Then the envelope of the family curves is composed of points p that satisfy

and

On the other hand, we find that the normal line of can be also given by Equation (2). Therefore, the a-antiorthotomic of is naturally defined as follows:

By the above notions, we can give an explicit parametrization of the a-antiorthotomic . Let be the modified unit normal vector of defined in Section 2, so that is a smooth vector field along even if is a cusp curve. Then can be given by

where is determined by the condition , which satisfies

Combining Equations (4) and (5), by a straightforward calculation, has two values:

For the choice of the a-antiorthotomic consists of two parts, and They are parameterized by

and

respectively. Specifically, we have if .

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the differential geometry of -cusp curves. Section 3 presents the proof that singular points of the generalized antiorthotomic sweep out the evolute of cusp curve, and establishes a one-to-one correspondence between antiorthotomics and cusp curves. In Section 4, we define parallels of cusp curves and explore the relationship between parallels and generalized antiorthotomics. Finally, in Section 5, we study the repeated antiorthotomics of cusp curves, and demonstrate how the k-th antiorthotomics is determined by the -cusp curves.

All maps considered here are differential of class .

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce some necessary notations and concepts of -cusp curves in the Euclidean plane. Let be a smooth curve, where is an open interval. If satisfies the following two conditions:

- (1)

- ,

- (2)

- ,

where n and m are integers satisfying and we say that is an -cusp point, and is an -cusp curve. It is known that the classical Frenet–Serret-type frame does not work for singular curves. Fortunately, C. Zhang and D. Pei introduced a new moving frame to study the geometric properties of -cusp curves as follows (for details, see [18]).

Let be an -cusp curve. Without losing generality, we choose as the cusp point in this paper. Define two unit orthogonal vectors as

and

where is the anti-clockwise rotation by on . and are called the modified tangent vector and the modified normal vector of , respectively. We refer to a modified frame of the -cusp curve , and we have the following formula:

where

and

The function is called the associate function of and denotes the sign function of .

In the field of differential geometry concerning regular curves, it is well-established that the evolute of a planar curve represents the locus of centers of osculating circles of the curve. An equivalent description states that the envelope of the normal lines of a planar curve defines its evolute. Now, we introduce the definition of the evolute of an -cusp curve. Let be an -cusp curve. Since is a regular curve in the case of we choose the arc length parameter s. Then represents the classical Frenet–Serret-type frame, and the evolute of is defined by:

where denotes the curvature function of If the evolute of is defined as follows:

It was proved in [18] that the value of depends on n and and the following holds:

- (1)

- if .

- (2)

- if .

- (3)

- if and m is even, the straight line spanned by is the asymptotic line of the evolute. Moreover, the evolute approximates the normal line of along the positive direction at .

- (4)

- if and m is odd, the straight line spanned by is the asymptotic line of the evolute. Additionally, the right (resp. left) side of the evolute approximates the normal line of along the positive(resp. negative)direction at .

3. Singularities of -Antiorthotomics

We investigate the a-antiorthotomic of an -cusp curve focusing on singularities in this section. The relationship between the singularities of a-antiorthotomics and the evolutes of cusp curves is elucidated as follows:

Theorem 1.

Let be an (n, m)-cusp curve with the modified frame and the a-antiorthotomic of Then the singularities of sweep out the evolute of

Proof.

Case 1: When , the arc length parameter s can be employed, yielding

If is a singular point of then Namely is a singular point if and only if

and

By calculation, we have

which means According to the definition of the evolute of a regular curve, we obtain that lies on the evolute of the cusp curve .

Case 2: When , we use the parameter t. We have

where is the associate function of . If is a singular point of then Namely is a singular point if and only if

and

When by calculation, we have

which means Moreover, depends on the relation between n and m, the same as the case for evolutes. By the definition of the evolute of an -cusp curve, the conclusion holds. The proof for the case of follows similarly. This completes the proof. □

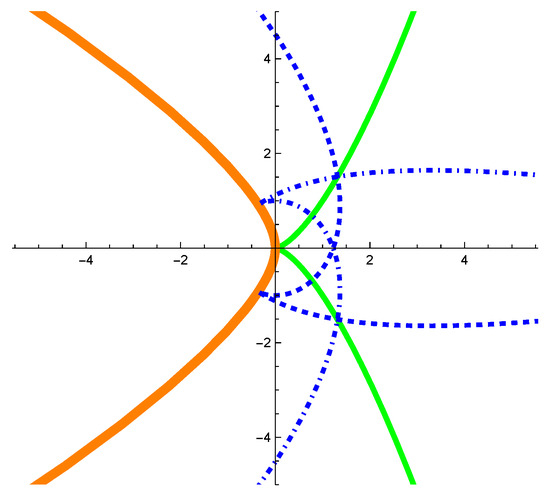

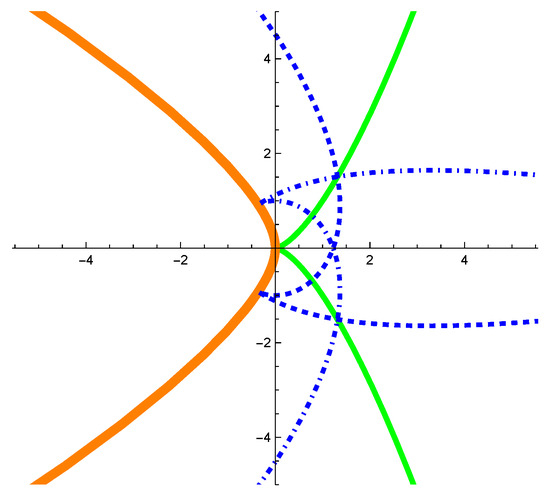

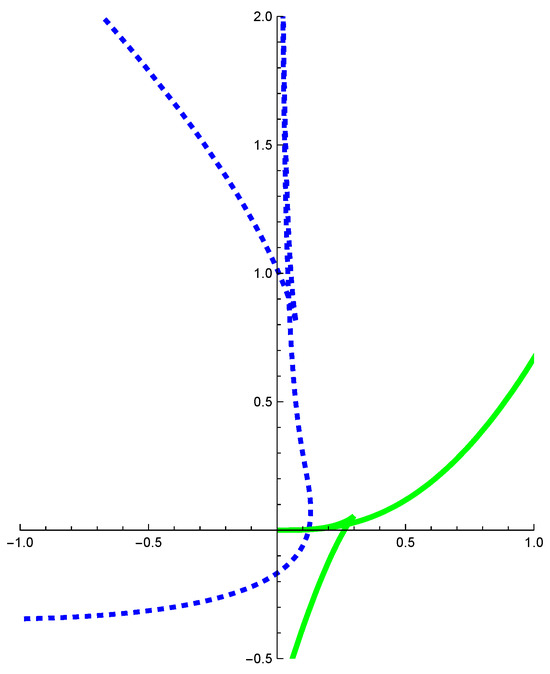

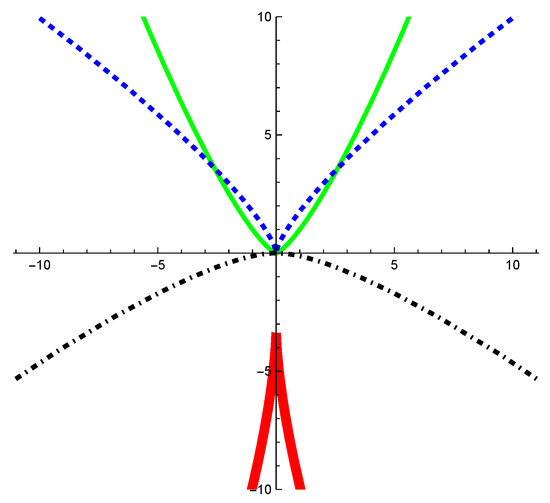

Example 1.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by It follows that

Take and according to Equations (7) and (8), and are parameterized by

and

respectively. By calculation, the evolute of is parameterized by

According to Theorem 1, the singularities of and both lie on (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The thin curve represents , the thick curve represents the dotdashed curve and the dashed curve represent and , respectively.

We discuss the behavior of the antiorthotomic of an -cusp curve at the cusp point. Let be an -cusp curve with the modified Frenet–Serret-type frame and If then the antiorthotomic of is given by

As is an -cusp curve and being its cusp point, it follows that and where signifies the infinitesimal of the same order as at Considering the value of

we have

Consequently:

- (1)

- When the antiorthotomic and coincide at meaning

- (2)

- When the antiorthotomic coincides with the normal line of at which means

- (3)

- When the normal line spanned by becomes the asymptotic line of the antiorthotomic. Additionally, if m is even, the two sides of the antiorthotomic approximate the normal line of infinitely along the same direction at If m is odd, the two sides of the antiorthotomic approximate the normal line of infinitely along the opposite direction at .

Proposition 1.

Let be an -cusp curve. Suppose that and , then is the -cusp point of the antiorthotomic and .

Proof.

From the above discussion, it follows that if According to Equation (12), we have

Moreover, we calculate that

and

where

Thus, we have

and

According to [14], is an -cusp curve with the cusp point where

Therefore, we have

This completes the proof. □

We provide some examples as follows.

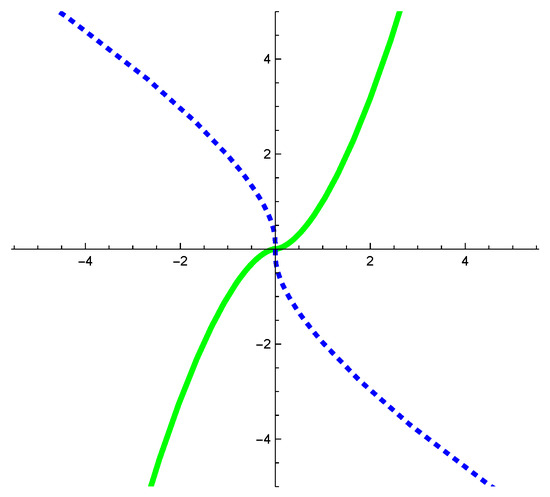

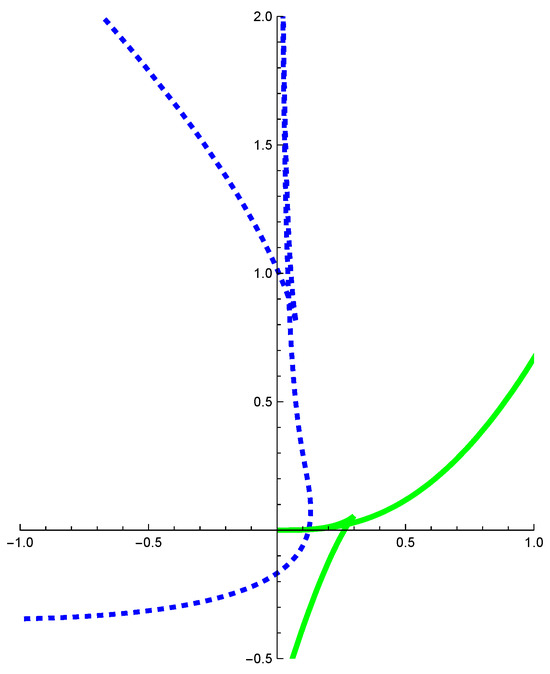

Example 2.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by It follows that

By Equation (12), we have

which is a -cusp curve. By Proposition 1, is a -cusp point of and By calculation, the evolute of is parameterized by

For , we have (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The solid curve represents and the dashed curve represents .

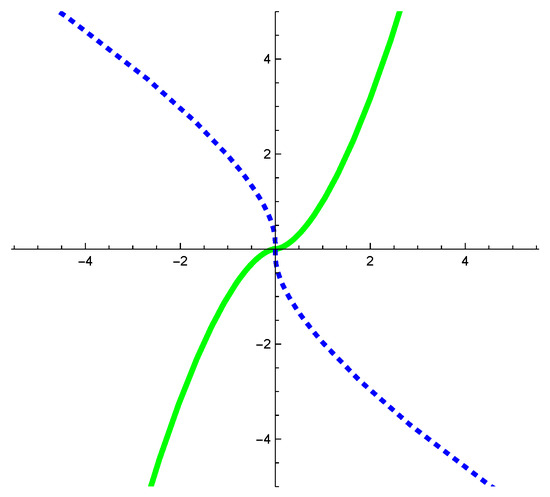

Example 3.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by

It follows that

By Equation (12), we have

and

Since the antiorthotomic coincides with the normal line of at (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The solid curve represents and the dashed curve represents .

Example 4.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by

It follows that

By Equation (12), we have

Since and m is even, the two sides of the antiorthotomic approximate the normal line of infinitely along the same direction at (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The solid curve represents and the dashed curve represents .

Example 5.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by It follows that

By Equation (12), we have

Since and m is odd, the two sides of the antiorthotomic approximate the normal line of infinitely along the opposite direction at (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The solid curve represents and the dashed curve represents .

4. Parallels and -Antiorthotomics of -Cusp Curves

In this section, we define parallels of an -cusp curve and investigate their relationship with a-antiorthotomics. Let be an -cusp curve with the modified Frenet–Serret-type frame A parallel of is a curve obtained by moving each point on along by a fixed distance b, which is defined as

Proposition 2.

Let be an -cusp curve with the modified frame and a parallel of Then the singularities of sweep out the evolute of

Proof.

By taking the derivative of , we have

where is the associate function. is a singular point if and only if Namely, is a singular point if and only if

When by calculation, we have

which means Moreover, depends on the relation between n and m, the same as the case for the evolute. According to the definition of the evolute of an -cusp curve, the consequent holds. This completes the proof. □

By combining Theorem 1 and Proposition 2, it is observed that the singularities of parallels and a-antiorthotomics both sweep out the evolute of . To further elucidate the relationship between parallels and a-antiorthotomics, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Let be an (n, m)-cusp curve with the modified frame and a parallel of Then we have the following assertions:

- (1)

- then

- (2)

- then

- (3)

- then

- (4)

- then

Here are constants.

Proof.

The following example is provided to illustrate Proposition 2 and Theorem 2.

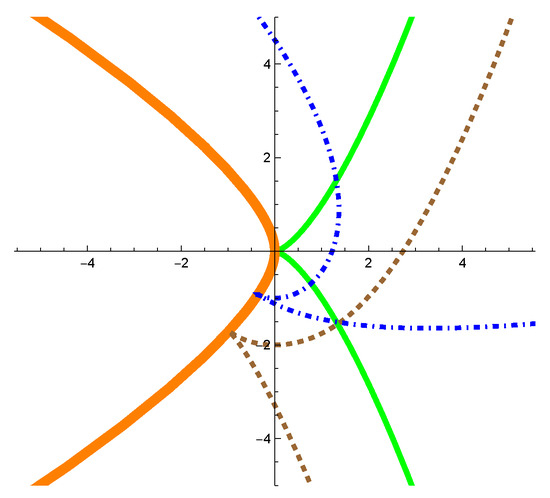

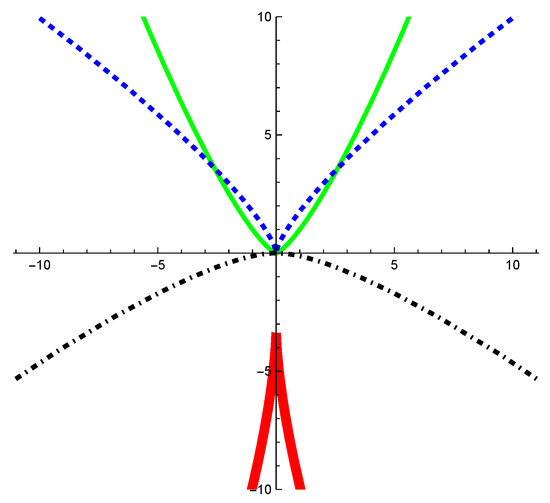

Example 6.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by Let and then the parallel of is parameterized by

By calculation, we have

According to Theorem 2, we also have Moreover, reviewing Example 1, the evolute of is parameterized by

According to Theorem 1 and Proposition 2, the singularities of and both lay on (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The thin curve represents , the thick curve represents the dashed curve represents and the dotdashed curve represents (or ).

5. -th Antiorthotomics of -Cusp Curves

In this section, we investigate the k-th antiorthotomic of an -cusp curve, which corresponds to the k-th mirror in the optical system. Let be an -cusp curve with the modified Frenet–Serret-type frame From now on, we denote the antiorthotomic as We delineate two distinct cases as follows.

Case 1: does not pass through the origin.

According to Equation (12), the representation of the 2-th antiorthotomic of is given by

where is the modified unit normal vector of .

Lemma 1.

Let be an -cusp curve with the modified Frenet–Serret-type frame Then the vector is parallel to .

Proof.

By Lemma 1, it follows from that

By repeating this process, we can obtain the k-th antiorthotomic of as follows:

where and denotes . More precisely, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

With the above notations and conditions, we have the following relationship:

Proof.

Case 2: passes through the origin. We study the k-th antiorthotomic subdividing into two cases based on whether the origin corresponds to the cusp point of .

Case 2a: . We assume that is the origin and .

When the expression for remains Equation (15).

When depends on the value of Specifically,

- (1)

- if then ;

- (2)

- if then ;

- (3)

- if then does not exist.

Case 2b: . The following theorem characterizes the relationship between and at the cusp point .

Theorem 4.

Let be an (n, m)-cusp curve and . If , then is a -cusp point of and where is a positive integer.

Proof.

Since and there must exist a unique such that

It is equivalent to

Proposition 1 implies that for is a -cusp point of and . This confirms that the consequent holds for If , assume the consequent holds for then is an -cusp point of and Since

it follows again from Proposition 1 that is an -cusp point of and Thus, the consequent holds for Moreover, because

By the analysis before Proposition 1, we obtain that which means that the consequent does not hold for This completes the proof. □

The above theorem shows that the number of repeated antiorthotomics of is entirely determined by m and We provide an example to demonstrate Theorem 4.

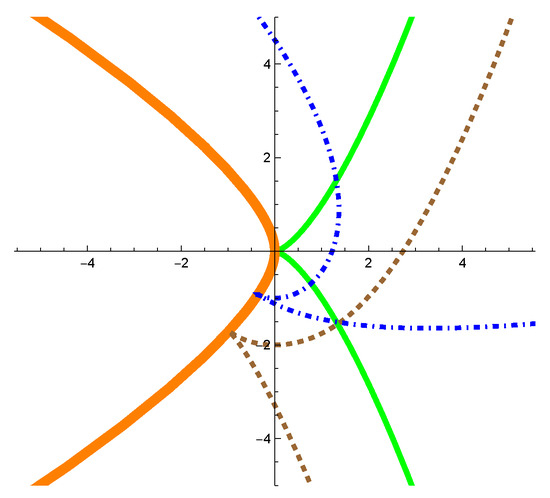

Example 7.

Let be a -cusp curve which is defined by Since then follows. By Theorem 4, and have cusp points at By calculation, we have

Then is obtained as follows:

which is a -cusp curve. By Theorem 4, it is also known that is a -cusp curve at and . By the representation of , we calculate that

Then is parameterized by

which is a -cusp curve. It also follows from Theorem 4 that is a -cusp curve at and . Moreover, we calculate as follows:

and it is clear that (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The thin curve represents the dashed curve represents the dotdashed curve represents the thick curve represents .

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have introduced generalized antiorthotomics of -cusp curves in the plane. We have then investigated the singular property of generalized antiorthotomics. Since evolutes and parallels can be explained as caustics and wavefronts, respectively, from the viewpoint of Legendrian singularity theory, we have established the connections between evolutes, parallels and generalized antiorthotomics. At last, we have studied the behavior of k-th antiorthotomics of -cusp curves which correspond to the multi-mirror in optics.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Q.Z. and Y.L.; Funding acquisition, Q.Z. and Y.C.; Resources, Q.Z.; Software, L.W.; Supervision, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, L.W. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author is supported by 2023 Project of Jilin University of Finance and Economics (Grant No. 2023YB025) and 2021 Entrusted Project by All-Time International Logistics (Dalian) (Grant No. 20220094). The corresponding author is supported by Youth Project of Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 20240115).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ates, F.; Ekmekci, N. Light patterns generated by the reflected rays. Optik 2020, 224, 165507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, F. Caustic points of the timelike curve on the de Sitter 3-space. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.; Giblin, P. Curves and Singularities, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, J.; Newman, E. The theory of caustics and wave front singularities with physical applications. J. Math. Phys. 2000, 41, 3344–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasse, W.; Kriele, M.; Perlick, V. Caustics of wavefronts in general relativity. Class. Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, 1161–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, Y. Adaptive optics wavefront correction using a damped transpose matrix of the influence function. Photonics Res. 2022, 10, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgato, S.; Chaves, J.; Mohedano, R.; Hernández, M.; Blen, J.; Grabovickic, D.; Thienpont, H.; Duerr, F. Prescribed intensity patterns from extended sources by means of a wavefront-matching procedure. In Proceedings of the 5th SPIE Conference on Illumination Optics, Frankfurt, Germany, 14–16 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizaki, Y.; Valdivia, M.; Horisaki, R.; Kitaguchi, K.; Saito, M.; Tanida, J.; Vera, E. Deep learning wavefront sensing. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J.; Manche, E. Quality of Vision After Wavefront-Guided or Wavefront-Optimized LASIK: A Prospective Randomized Contralateral Eye Study. J. Refract. Surg. 2016, 32, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.D. Light caustics of hydrodynamic solitons illuminated by a laser beam. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 4069–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, G.D. Properties of caustics of a plane curve illuminated by a parallel light beam. Opt. Commun. 1994, 106, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, P.E. Geometric optics of a refringent sphere illuminated by a point source: Caustics, wavefronts, and zero phase-fronts for every rainbow “k” order. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2018, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer, O.O.; Gök, I. Hyperbolic caustics of light rays reflected by hyperbolic front mirrors. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quételet, L.A. Mém; Royal Academy of Archaeology of Belgium: Brussels, Belgium, 1892; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J. Spherical orthotomic and spherical antiothotomic. Acta Math. Sin. 2007, 23, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamo, N.; Criado, C. Generalized antiorthotomics and their singularities. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, T. Local differential geometry of singular curves with finite multiplicities. Saitama Math. J. 2017, 31, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Pei, D. Evolutes of (n, m)-cusp curves and application in optical system. Optik 2018, 162, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pei, D. Duality of the evolute-involute pair and its application. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 72072–72075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, A.; Yao, K.; Pei, D. Generalized Bertrand curves of non-light-like framed curves in Lorentz-Minkowski 3-Space. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Pei, D. Nullcone fronts of spacelike framed Curves in Minkowski 3-Space. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, H. Singularities of helix surfaces in Euclidean 3-space. J. Geom. Phys. 2020, 156, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, H. Generalized evolutes of planar curves. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2021, 18, 2150222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, H. Pseudo-spherical evolutes of lightlike loci on mixed type surfaces in Minkowski 3-space. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 7598–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M. Geometry II; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).