Abstract

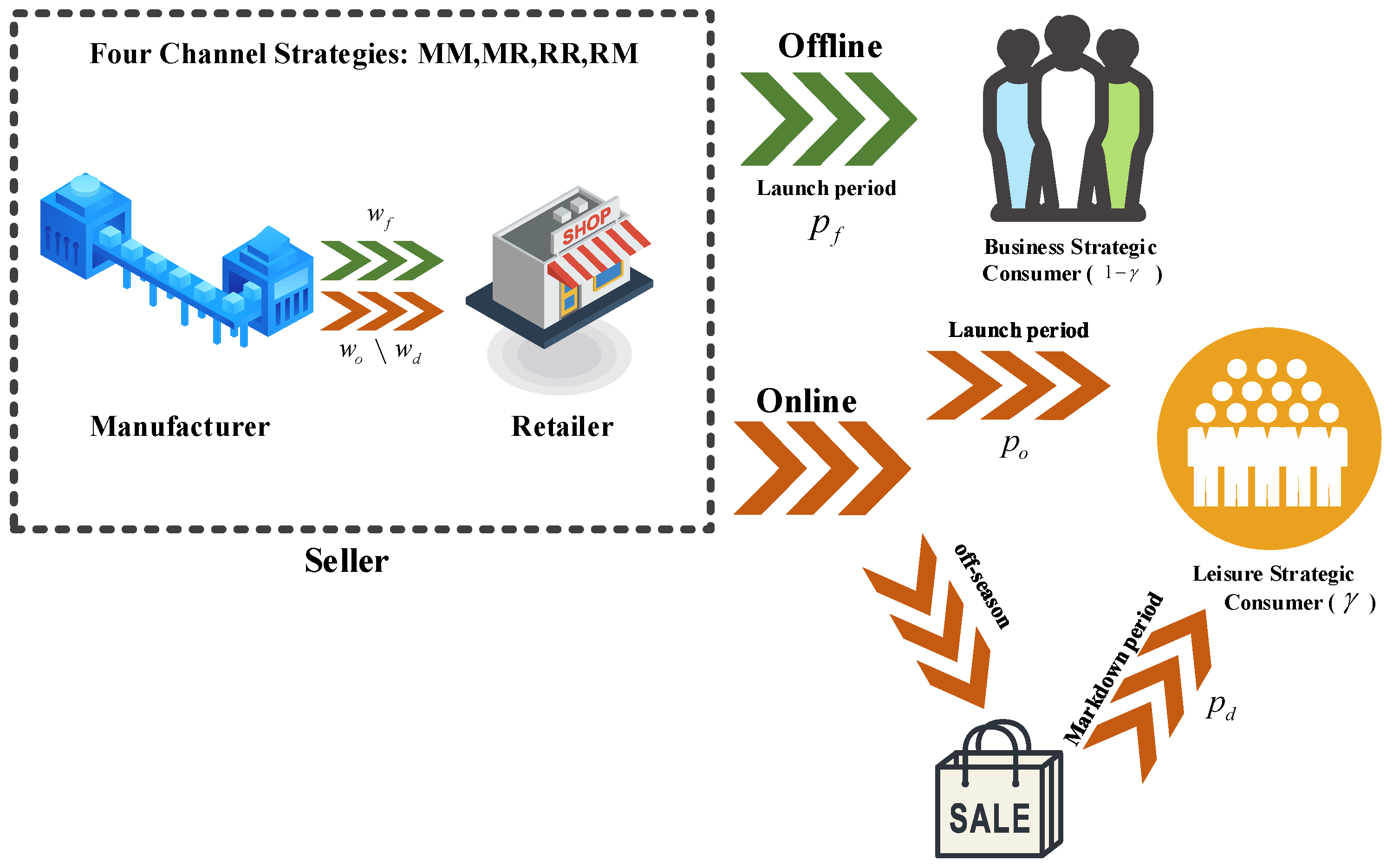

Fashion products are typically sold through both online and offline channels during two distinct phases: the launch and markdown period. Pricing strategies present significant challenges for manufacturers, particularly as consumers increasingly adopt strategic purchasing behaviors. Key factors, including product fashion utility, purchase timing, and consumer characteristics, complicate manufacturers’ channel selection, pricing decisions, and service strategy formulation—necessitating deeper investigation. This paper establishes a two-echelon supply chain model featuring a fashion manufacturer and a retailer to determine optimal channel, pricing, and service strategies across both selling periods amid strategic consumer behavior. We examine four channel strategies: (1) the MM strategy: the manufacturer operates both channels (online and offline channels) during both periods (launch and markdown period); (2) the MR strategy: the manufacturer operates both channels during the launch stage, and the retailer sells online during the markdown period; (3) the RR strategy: the manufacturer sells offline, and the retailer operates the online channel during both stages; (4) the RM strategy: the manufacturer sells online during both stages, and the retailer sells through the offline channel. Our analysis yields critical insights: When off-season discounts are limited, the manufacturer should maintain direct control of both channels. However, when the off-season discount is significant, the manufacturer needs to set the channel strategy according to the fashion utility. If the fashion utility is small, direct sales through offline channels during the launch period, while entrusting the retailer to distribute in online channels during both periods, should be adopted. If the fashion utility is large, a dual-channel, two-stage, entirely direct sales strategy should be adopted. This study elucidates the optimal manufacturer channel and pricing strategy options and provides some theoretical contributions and practical implications.

MSC:

90-10

1. Introduction

In recent years, consumer interest in fashion items has surged, with increasing emphasis on the pursuit of style and fashion. The fashion industry experienced a 21 percent increase in revenues from 2020 to 2021, while EBITA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, and Amortization) margins doubled, rising by 6 percentage points to 12.3 percent (Source: The State of Fashion, McKinsey & Company, Chicago, IL, USA). This rapid growth has attracted attention from both industry and academia, sparking extensive research on fashion product sales [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Fashion products embody both aesthetic and practical value. Traditionally, many fashion manufacturers have preferred direct-to-consumer sales, particularly in regions like Europe, where artisanal heritage is deeply rooted. Florentine leather workshops producing luxury handbags, for instance, historically operated exclusively through physical storefronts or local markets. However, e-commerce’s rise has transformed distribution; fashion products are now increasingly sold via dual-channel strategies (online/offline) across two key phases: launch period and discount period. Consider Bridge, a Florentine heritage brand: previously known for window-displayed leather bags, it now showcases collections on digital platforms—signaling a shift from traditional offline retail to digitally enabled omnichannel reach.

Fashion products initially enter the market with high symbolic value during the launch period, appealing to consumers driven by identity expression, novelty, and trend sensitivity. In contrast, during the markdown period, practical value dominates, attracting price-sensitive consumers who prioritize function over symbolism [1]. This value transition coincides with consumers’ unprecedented access to multi-channel information—from trend discovery via YouTube/Instagram to product searches on Temu and Taobao’s image recognition in Asia—enabling more strategic purchasing behavior than ever before. To maximize utility, strategic consumers evaluate not only fashion product attributes—functional versus stylistic—but also purchasing channels (online/offline) and timing (launch/discount periods). Furthermore, preference heterogeneity across consumer segments drives divergent priorities regarding product features and price sensitivity. For instance, leisure-focused strategic consumers exhibit greater price sensitivity and frequent cross-channel price comparisons, demonstrating minimal concern about online return/exchange risks. Conversely, business-oriented strategic consumers display stronger risk aversion toward returns or exchanges while placing higher valuation on product fashion elements.

Consequently, the strategic selection of sales channels for fashion products by enterprises is influenced by multifaceted factors, including product attributes (e.g., fashion versus practical utility, seasonal renewability) and consumer preferences. As Table 1 summarizes, companies adopt varied strategies to address these factors. For instance, ZARA assigns all sales operations to the manufacturer, selling through manufacturer-managed online/offline channels during both launch and discount periods while implementing a “small-lot, multi-style” strategy to ensure sell-through at launch [1]. Conversely, GAP utilizes hybrid channel management: distributing through both manufacturer and retailer channels across periods, launching seasonal collections quarterly, and implementing end-of-season discounts through multiple channels.

Table 1.

Fashion Product Sales Channels by Period (Launch vs. Markdown).

Given the diverse performance outcomes of enterprises in channel selection—exemplified by ZARA and GAP—the following questions arise: How does the fashion product’s fashion and function utility in different periods affect the demand in both channels (online and offline channels) during the two periods (launch and markdown period)? How does consumers’ preference affect entrepreneurs’ (manufacturers and retailers) selling strategies? Some scholars have studied the consumers’ demand for fashion products in different channels [9,10,11,12]. Kim and Lee [9] conducted an online survey to examine the cross-channel spillover effect of price promotion and proved that these effects depend on brand trust. Lee et al. [10] applied a D-optimal discrete choice conjoint design and proposed the optimal combination of key fashion product and channel attributes that is most preferable to consumers in the multi-channel environment. These studies have yielded exciting conclusions, providing a solid research foundation for this article. However, these studies have overlooked the impact of the fashion level of the product, the selling period, and the consumers’ characteristics on channel selection, pricing, and service.

To bridge these gaps, this study develops a two-echelon supply chain model comprising a fashion product manufacturer and a retailer. The manufacturer produces fashion products and can either sell them wholesale to the retailer or directly to consumers via online and offline channels. The market consists of two types of strategic consumers—business and leisure—who exhibit different preferences for the fashion and functional utilities of products. The analysis focuses on four potential channel strategies: MM, MR, RR, and RM. Referring to Guo et al. [13], Zhao et al. [14], Xia et al. [15], He et al. [16], Song et al. [17], Yang et al. [18], and Qin [19], the strategies such as MM, MR, RR, and RM in our paper are all pre-decision-making strategies of enterprises. The MM strategy corresponds to the example of traditional channel strategy, with the manufacturer always directly selling products to the consumers. MR, RR, and RM strategies correspond to the outsourcing problems in supply chain management. This study reveals fashion product manufacturers’ optimal channel (online or offline), pricing, and service strategies considering the strategic consumers in two periods (launch and markdown periods) and addresses the following questions:

- (1)

- How should the manufacturer implement channel strategies accounting for the changes in the fashion utility of the fashion product during the launch and markdown periods?

- (2)

- How does fashion utility affect the optimal pricing and service level of manufacturers and retailers?

- (3)

- How do the proportion of business and leisure strategic consumers in the market and their preference towards fashion impact the entrepreneurs’ optimal pricing and service strategies?

This work offers several theoretical contributions and practical implications. First, it extends prior research by analyzing the behavior of two types of strategic consumers in the context of dual-channel sales across two selling periods. The findings yield insightful theoretical outcomes and valuable managerial implications, offering guidance for firms engaged in the production and distribution of fashion products. Specifically, the study reveals that the manufacturer’s optimal channel strategy depends on both the fashion utility of the product and the magnitude of the off-season discount. When the off-season discount is small, the manufacturer should adopt direct sales (MM strategy) in both online and offline channels. However, when the off-season discount is significant, the manufacturer needs to set the channel strategy according to the fashion utility. If the fashion utility is small, direct sales through offline channels during the launch period, while entrusting the retailer to distribute in online channels during both periods (RR strategy), should be adopted by the manufacturer; if the fashion utility is large, a dual-channel, two-stage, entire direct sales strategy should be adopted (MM strategy).

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature. Section 3 establishes model specifications, notations, and critical assumptions. We develop analytical models in Section 4. Building on this foundation, Section 5 analyzes optimal channel strategies, Section 6 presents numerical examples, and Section 7 provides concluding remarks. All proofs appear in the supplementary materials.

2. Literature Review

This study integrates three research domains: fashion products (inspiration for research questions), strategic consumers, and multi-channel systems (theoretical foundations for analyzing consumer behaviors and omnichannel strategies). We will review each of them below.

2.1. Fashion Products

Current scholarly research on fashion products primarily focuses on three aspects: seasonal characteristics and pricing (e.g., [20,21,22,23]), sales channel selection (e.g., [1,15,24]), and consumer/social influences (e.g., [11,12,25]). For instance, Backs et al. [20] compared supply chains in fast fashion versus traditional fashion industries, examining product and communication strategies across market scenarios. Namin et al. [21] analyzed seasonal characteristics of fashion products to demonstrate retailer markdown policies under demand uncertainty. Cho et al. [22] subsequently extended research on sustainable labeling specificity to fashion retail. Bae and Cho et al. [23] developed a system of differential equations establishing mathematical standards for characterizing fashion versus classic items. Regarding channel selection, Xia et al. [15] investigated social factors’ impact on channel sequencing and pricing within dual-channel luxury distribution frameworks, whereas Alom et al. [1] proposed optimal contracts considering single versus dual shipment policies. Lu and Yan [24] constructed mathematical models using deterministic fashion-level functions, highlighting the critical need to incorporate random factors in decision-making. Further examining consumer influences, Kullak et al. [11] applied job-to-be-done theory to classify fashion product needs into social and personal dimensions. This consumer behavior perspective extends to Wu and Lee [12], who analyzed relationships between consumption value and purchase intention, and Lee and Cho [25], who demonstrated how luxury social media posts positively influence attitudes toward account holders through intrinsic motivation attribution. While these studies inform our research questions and provide theoretical foundations for modeling seasonal characteristics and purchase intentions, they collectively overlook strategic consumers’ differentiated purchasing behaviors and the impact of multi-channel factors on fashion sales.

2.2. Strategic Consumers

As consumers gain access to increasingly diverse information channels, they make more purposeful choices regarding channels and products to maximize personal utility, leading to increasingly strategic consumption behavior. This trend has prompted scholarly investigation into strategic consumer characteristics and their impact on purchasing decisions (e.g., [13,14,16,17,26,27,28,29,30]). For instance, Su [26] defined rational consumer behavior as purchasing at current prices, remaining in the market at a cost for future purchases, or exiting—with decisions based on utility maximization. Su further developed a dynamic pricing model examining its impact on demand over time. Guo et al. [13] investigated two-period intertemporal service pricing for strategic consumers. Qiu et al. [27] examined two-stage pricing strategies for agile retailers facing strategic consumers, proposing a distributed robust optimization method. He et al. [16] demonstrated that dual-channel firms should implement preannounced rather than dynamic pricing when serving strategic consumers. Song et al. [17] studied supply chain coordination with boundedly rational strategic customers, while Liu et al. [28] addressed contextual dynamic pricing for strategic buyers. Scholars have also applied strategic consumer frameworks to specialized product contexts: Workman and Lee 30 extended cognitive dissonance theory through fashion trendsetters’ post-purchase evaluations and monetary attitudes, whereas Zhao et al. [14] analyzed dual-period decision-making for short-life-cycle products in strategic consumer markets. While these studies provide valuable theoretical foundations, most lack detailed classification of heterogeneous strategic behaviors across consumer segments. This gap is particularly critical for fashion products—highly seasonal goods sold through multiple channels across launch and markdown periods—where understanding how different strategic consumer types (e.g., leisure-focused strategic consumers vs. business-oriented strategic consumers) navigate channel choices remains under-explored.

2.3. Multi-Channel Systems

The proliferation of the internet and e-commerce has made multi-channel sales a significant research focus (e.g., [18,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]). Current studies examine channel strategies through two primary lenses: Retailer perspectives, Xu et al. [31] experimentally demonstrated how consumer attitudes and demands diverge across online versus offline channels, confirming that shopping channels influence psychological distance and subsequent decision-making. Yang et al. [18] proposed a tri-channel model with asymmetric retailers, analyzing three configurations: initial dual-channel systems, multi-channel e-platforms, and coordinated online-offline fulfillment integration. Parallel research on manufacturer-led direct channels reveals strategic implications: Lin et al. [32] established that manufacturer e-platforms effectively disrupt retailer collusion, boosting profits across the supply chain, while Lei and He [33] modeled hybrid structures where manufacturers conduct direct online sales while wholesaling to offline retailers. Extending this line of inquiry, scholars have incorporated sustainability and financial dimensions into multi-channel research. Wang et al. [34] identified how sustainability-conscious consumers compel firms to internalize environmental externalities in channel planning, whereas Qin [19] examined supplier model selection criteria and platform credit allocation to offline channels. Collectively, these studies confirm channel selection’s critical impact on demand and profitability. However, they overlook two crucial dimensions: (1) Strategic consumer behaviors in multi-channel environments and (2) fashion-specific attributes (e.g., seasonal symbolism, aesthetic utility) that fundamentally differentiate fashion products from general merchandise in channel strategy formulation.

Existing studies have investigated sales issues in fashion products and demonstrated that channel choice impacts demand and manufacturer profits, providing the inspiration and theoretical basis for this paper. Nevertheless, a significant gap remains: prior studies have overlooked the combined influence of strategic consumers’ differentiated purchasing behavior and temporal changes in product value (between launch and discount periods) on manufacturers’ multi-channel strategies (a summary and comparison of relevant literature is presented in Table 2). To address this, our study conducts an in-depth analysis of fashion manufacturers’ channel choices across key product lifecycle phases (launch and discount periods), explicitly incorporating consumer strategic behavior and product value dynamics. The resulting insights enrich current theoretical understanding and provide valuable decision-making references for enterprises.

Table 2.

Summary of related literature.

3. Model Specifications and Parameter Definition

This paper considers a supply chain consisting of a fashion product manufacturer, who acts as the Stackelberg leader, and a retailer as the follower. The manufacturer produces fashion products that possess both functional and fashion features at a unit cost of , contributing to their practical utility and symbolic value—referred to as functional utility and fashion utility , respectively. For example, Air Jordan sneakers serve a dual purpose: they provide comfort and support as athletic footwear (functional utility), while also acting as a status symbol and fashion statement (fashion utility), particularly due to their cultural significance and celebrity endorsements. Similarly, a Louis Vuitton handbag offers practical utility by enabling users to carry personal items, while simultaneously conveying brand prestige and social identity through its design and logo prominence.

This fashionable product is sold both online and offline during the launch and discount period. The manufacturer can sell the fashion product through both channels during both stages (the MM strategy) and can choose whether to entrust the retailer to sell the product through online channels (the MR strategy or the RR strategy) or offline channels (the RM strategy). The strategies such as MM, MR, RR, and RM are all pre-decision-making strategies of the manufacturer [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. And the manufacturer usually sets different wholesale prices for their products on both online and offline channels. For instance, when Adidas launched limited edition sports shoes, it offered selective wholesale pricing arrangements to brick-and-mortar retailers (such as Foot Locker), while when distributing the same product through third-party online markets (such as Zalando), the wholesale prices were usually different. Therefore, we assumed that during the launch period, the manufacturer unit wholesale price is denoted as and in the offline and online channels, respectively. During the markdown period, there is a particular discount on the wholesale price, denoted as . In addition, the fashion product is sold to consumers at a unit price .

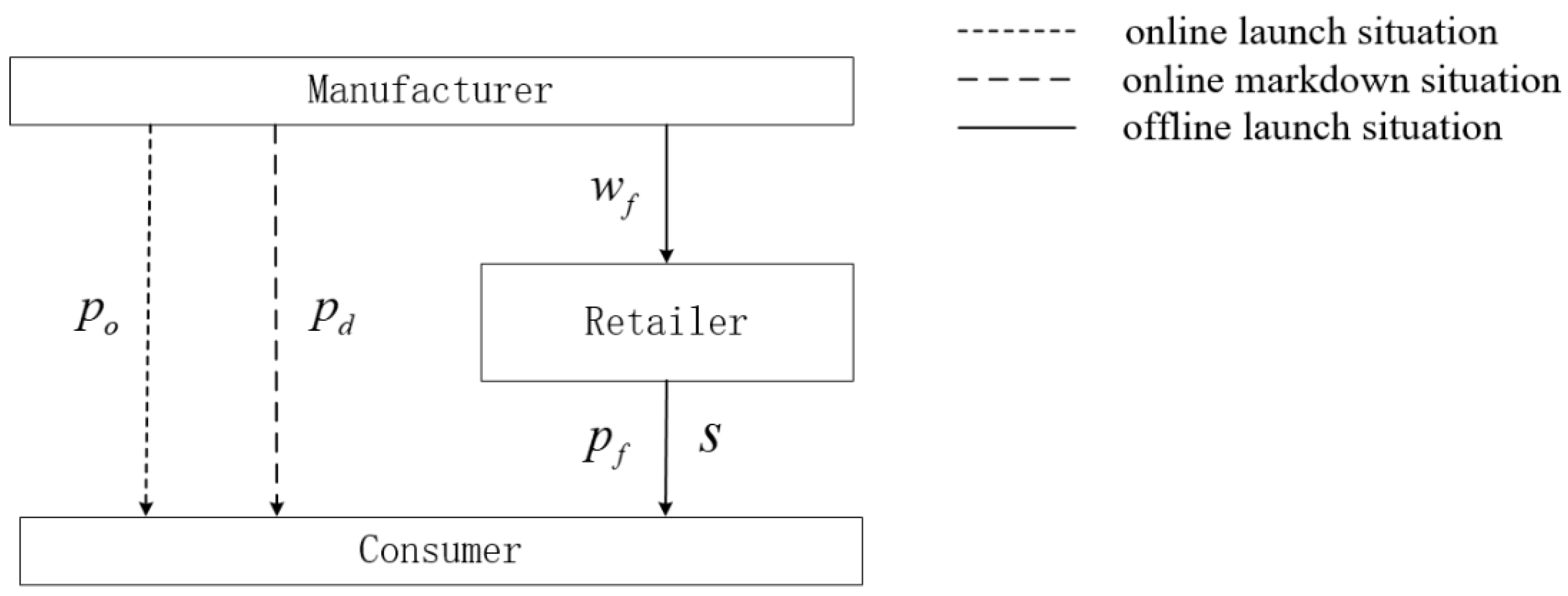

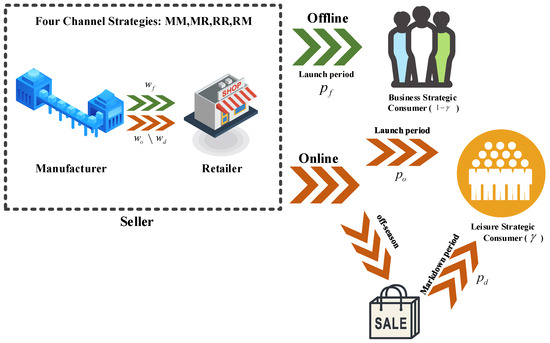

Additionally, referring to Xia et al. [15], He et al. [16], Su [26], and Qiu et al. [27], we assume that there exist two types of strategic consumers: one is the leisure strategic consumer (accounting ), who tends to compare prices among channels and is price sensitive and does not consider the risk of returning or exchanging goods purchased online; the other is the business strategic consumer, who is risk-averse about returning or exchanging goods and values the fashion of the product (accounting ). Due to their different preferences, these two types of strategic consumers exhibit distinct purchasing behaviors, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model Structure and Consumer Decision Pathways.

During the launch period, the prices of fashion products were high in offline channels. For the leisure strategic consumers, they will choose between purchasing during the launch and markdown period through the online store. But, considering the potential risks of returns resulting from online purchases, the business’s strategic consumers will only choose to purchase in physical stores during the launch period. These phenomena are very common; for example, when GAP launches a new product, business strategic consumers will go to the physical stores and try on the clothes immediately. However, another group of consumers, the leisure strategic consumers, tend to observe the products’ information online and decide whether to purchase immediately or wait until the markdown period.

For the leisure strategic consumers, the utility obtained when purchasing one unit of product through the online launch period and markdown period can be expressed respectively as and , where is an off-season discount. And for the business strategic consumers, the utility obtained when purchasing one unit of product through an offline channel can be expressed as , where is the utility increased by the offline service. Following Lin et al. [32], we represent the service cost as , it is related to the level of service quality. And the () is the conversion coefficient of service.

When , the business strategic consumers will purchase through the offline channel during the launch period. Thus, we have the demand as . When and , the leisure strategic consumers will purchase through the online channel during the launch period. Thus, the demand is . Similarly, when and , the leisure strategic consumers will purchase through the online channel during the markdown period. Thus, the demand is obtained as follows: .

The proof is provided in the supplementary materials.

This paper studied the fashion product’s two-stage multi-channel and pricing problem, and the optimal selling prices, wholesale prices, service level, and profits of the manufacturer and retailer are analyzed under four channel strategies (the MM strategy, the MR strategy, the RR strategy, and the RM strategy). The superscripts “”, “”, “”, and “” respectively refer to the four scenarios. The manufacturer and retailer engage in a Stackelberg game under different strategies, aiming to maximize their own profits, to determine the wholesale prices, selling prices, and service levels of the products at each stage [15,17,18,19,32]. The superscript “” indicates an equilibrium solution, and the subscripts “m” and “r” indicate the manufacturer and retailer, respectively. The subscripts “”, “” and “” refer to the online channel and offline channel in the launched period and the markdown (discount) period, respectively. The parameters are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Notation.

4. Models

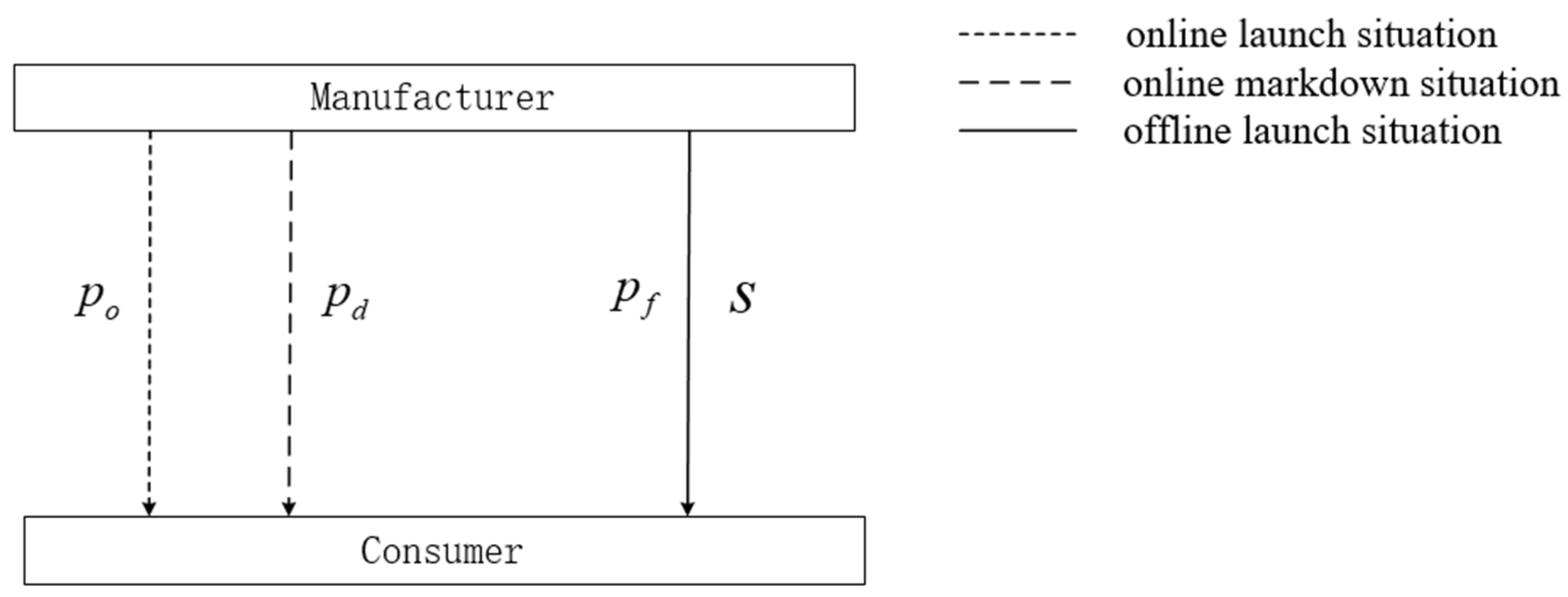

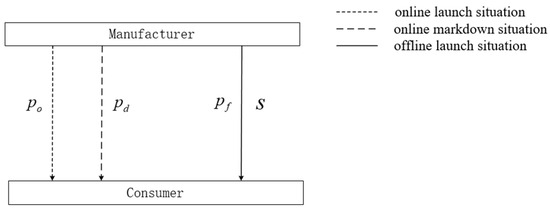

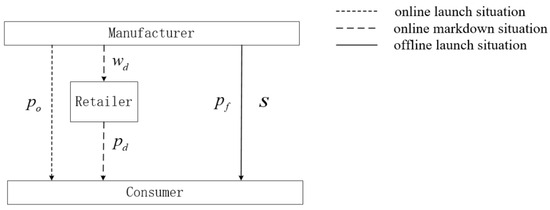

4.1. The Manufacturer Sells Product Through Multi-Channel (MM Strategy)

In this scenario, the manufacturer sells fashion products through both online and offline channels during all periods [16,35]. Specifically, it operates under three distinct sales arrangements across launch and discount periods: online launch sales, online discount sales, and offline launch sales. As shown in Figure 2. This situation is very common; Lululemon exemplifies a manufacturer-driven, multi-channel direct-to-consumer (DTC) strategy. The company sells its products exclusively through its own retail stores and official online platform, maintaining full control over pricing, inventory, and customer engagement across both the launch and markdown periods.

Figure 2.

MM Strategy.

As shown in Figure 2, on the online channel, the manufacturer’s unit selling price during the launch period is , during the markdown period is . On the offline channel, the manufacturer’s unit selling price is , and the service level is .

The profit of the manufacturer in the launch period and markdown period can be expressed as follows.

The manufacturer will decide on the selling prices and the service level to maximize its profit.

Property 1.

When the manufacturer produces and sells fashion products through multi-channel during both periods, (1) the manufacturer’s profit function in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling prices , and service level . (2) The manufacturer’s profit function in the markdown period is concave with respect to the selling price .

Because the profit of the manufacturer in the launch and markdown periods are respectively concave with respect to , , and the optimal variables can be found to maximize the profit function. The results are summarized in Proposition 1.

Proposition 1.

In the MM scenario, the optimal selling prices and service level are, respectively,

, , , and , and the manufacturer’s total profit in the two periods is

Proposition 1 also states that when the manufacturer produces and sells fashion products through multi-channel during both stages, we have the selling price . During the launch period in the online channel, the selling price is higher than the markdown period. It is in line with reality.

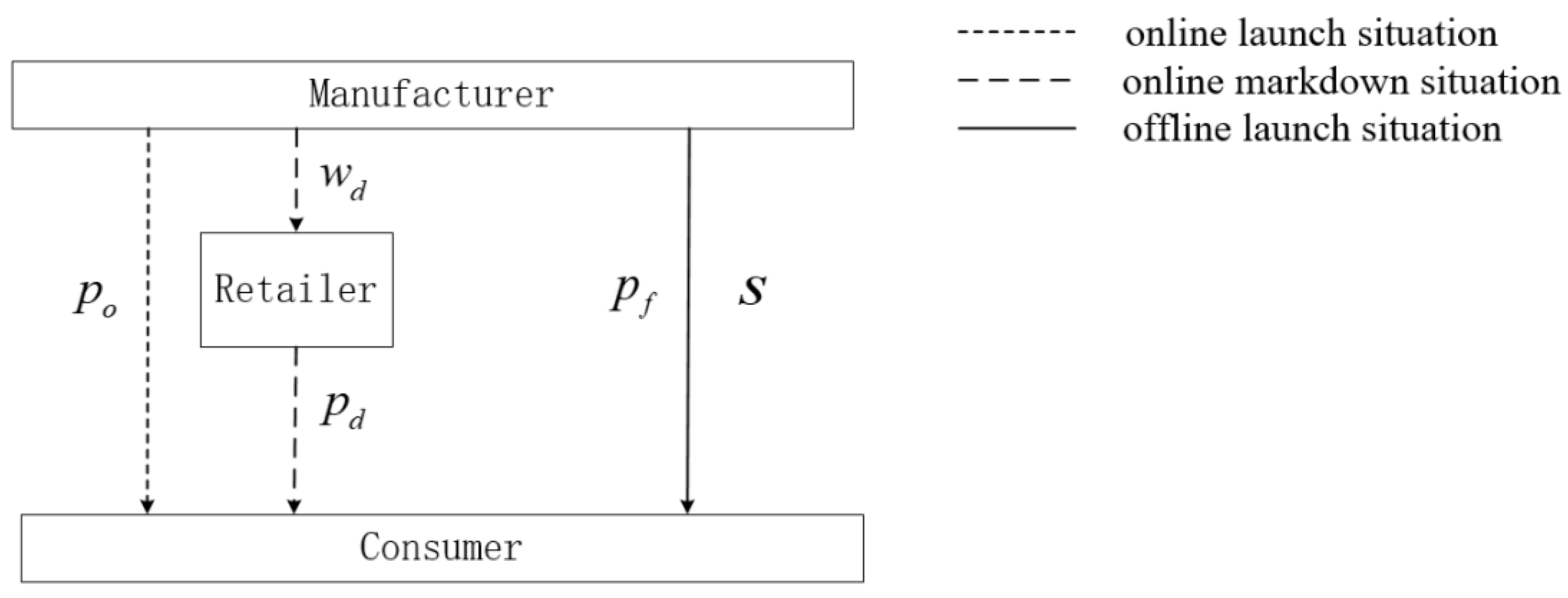

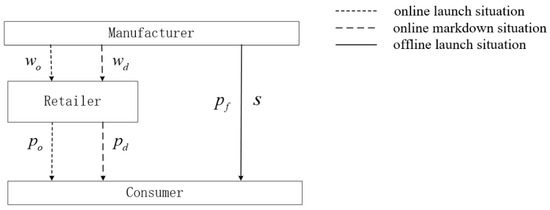

4.2. The Manufacturer Operates a Launch Period Sale and Retailer Markdown Period (MR Strategy)

In this scenario, the manufacturer entrusts the retailer with the markdown period of online sales and operates multi-channel (online and offline) sales during the launch period [15,31,36]. The MR strategy finds practical application in Adidas’ partnerships with outlet operators. During launch periods, Adidas distributes new collections exclusively through company-owned retail stores and its direct e-commerce platform (adidas.com). Subsequently, unsold inventory transitions to third-party outlet operators during markdown periods, where pricing and promotional authority shift to retailers. This arrangement maintains manufacturer control during high-value launches while delegating inventory clearance responsibilities—including associated risks—to retailers through discount-focused online channels during markdown phases. See Figure 3: MR Strategy.

Figure 3.

MR Strategy.

As shown in Figure 3, during the product launch period, the manufacturer set the unit selling price on the online channel at , the unit selling price on the offline channel at , and the offline service level at . During the markdown period of online channel, the unit wholesale price set by the manufacturer is , and the unit selling price set by the retailer is .

The profit functions of the manufacturer in the launch and markdown periods and the profit functions of the retailer can be expressed as follows.

Property 2.

When the manufacturer entrusts the retailer with the markdown period of online sales and conducts multi-channel sales during the launch period, (1) the manufacturer’s profit in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling prices , and service level . (2) The manufacturer’s profit in the markdown period is concave with respect to the wholesale price . (3) The retailer’s profit in the markdown period is concave with respect to the selling price .

Because the profits of the manufacturer and retailer are respectively concave with respect to , , , and , the optimal variables can be found to maximize the profit. The results are summarized in the following Proposition 2.

Proposition 2.

In the MR scenario, the entrepreneurs’ optimal selling prices, service level and wholesale prices are, respectively

, , ,

and , and the manufacturer’s total profit in the two periods is

The retailer’s total profit is .

Proposition 2 also states that when the manufacturer entrusts the retailer with the markdown period of online sales and conducts multi-channel sales during the launch period, we have the selling price . In the online channel, the selling price of the newly launched product is higher than that in the markdown periods. It is in line with reality.

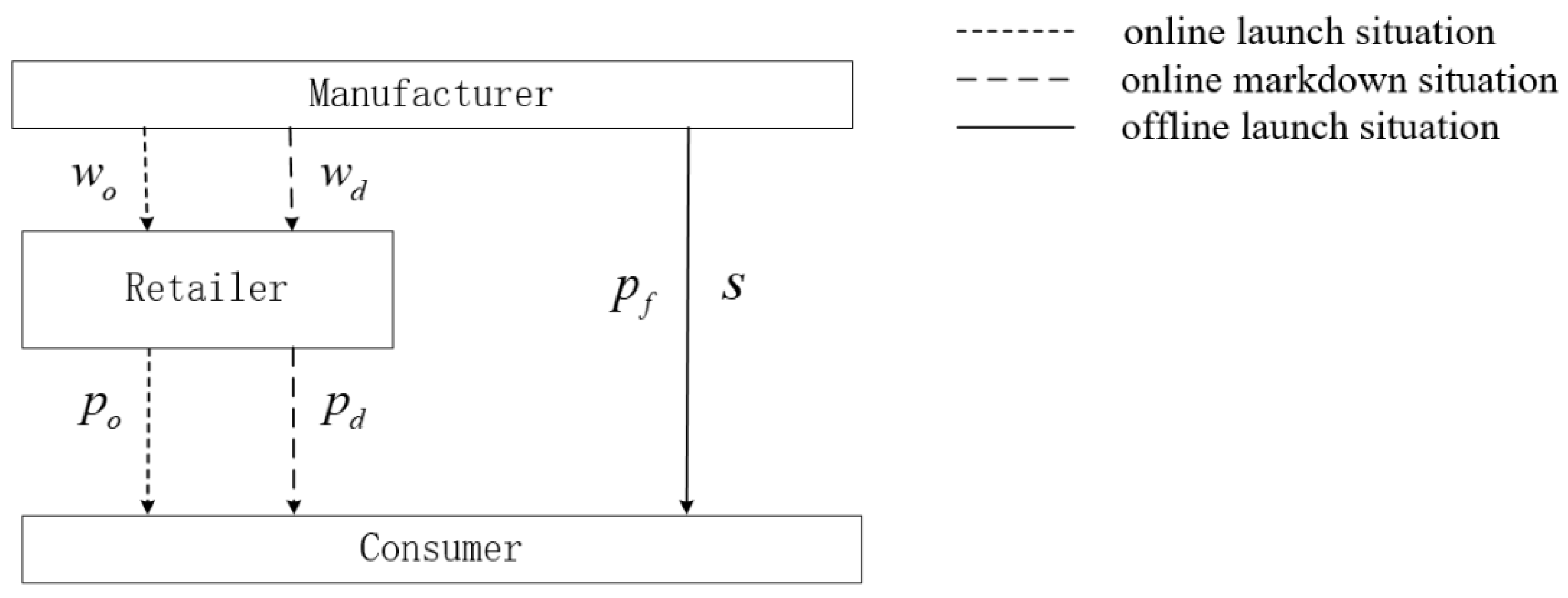

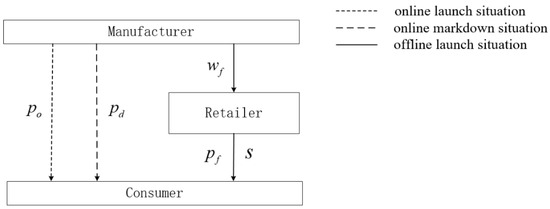

4.3. The Manufacturer Manages Offline Channel and the Retailer’s Online Channel (RR Strategy)

In this situation, the manufacturer has given the retailer responsibility for online sales in both periods and operates offline sales during the launch period [1,20]. Luxury fragrance brands like Dior and Chanel exemplify the RR strategy through their department store partnerships. These manufacturers maintain exclusive offline control via branded counters in premium retailers (Harrods, Galeries Lafayette, Isetan), particularly during launches wherein in-person consultation and experiential marketing prove essential. For online operations, however, both launch and markdown activities are delegated to retailer e-commerce platforms such as Sephora or Selfridges. Under this model, retailers assume full operational control—setting prices; managing promotions; and clearing inventory—while manufacturers preserve brand exclusivity through high-touch offline experiences while leveraging retailers’ digital infrastructure for online distribution. As shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

RR Strategy.

During the launch period of the offline channel, the manufacturer set the unit selling price at , and the offline service level at . On the online channel, during the product launch and markdown period, the manufacturer’s wholesale prices are , , and the retailer’s selling prices are , .

The manufacturer’s and retailer’s profit in the launch and markdown periods can be expressed as follows:

Property 3.

When the manufacturer entrusts the retailer with online sales and conducts offline sales, (1) the retailer’s profit in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling price . (2) The manufacturer’s profit in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling prices wholesale price and service level . (3) The retailer’s profit in the markdown period is concave with respect to the selling price . (4) The manufacturer’s profit in the markdown period is concave with respect to the wholesale price .

Because the profits of the manufacturer and retailer are respectively concave with respect to , , , , ,

and , the optimal solution can be found to maximize the profit function. The results are summarized in Proposition 3.

Proposition 3.

In the RR scenario, entrepreneurs’ optimal selling prices, service level, and wholesale prices in the newly launched period and markdown period are, respectively , , . , , , and the manufacturer’s total profit in the two periods is: The retailer’s total profit is .

Proposition 3 also states that when the manufacturer entrusts the retailer with online sales and conducts offline sales during the launch period, we have the selling price . In the online channel, the selling price in the launch periods is higher than in the markdown periods. It is in line with reality.

4.4. The Manufacturer Manages Online Channel and Retailer Offline Channel (RM Strategy)

In this scenario, the manufacturer entrusts the retailer to conduct sales for the offline channel while conducting online sales [32,33]; see Figure 5: RM Strategy.

Figure 5.

RM Strategy.

As shown in Figure 5, on the offline channel, the manufacturer set the wholesale price at , the retailer set the selling price at and the offline service level at . On the online channel, during the product launch and markdown period, the manufacturer’s selling prices are , .

The profits of the manufacturer and retailer can be expressed as follows.

Property 4.

When the manufacturer entrusts the retailer to conduct sales for the offline channel while conducting sales for both online stages, (1) the retailer’s profit in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling price and service level . (2) The manufacturer’s profit function in the launch period is concave with respect to the selling prices and wholesale prices . (3) The manufacturer’s profit in the markdown period is concave with respect to the selling price .

Proposition 4.

In the RM scenario, entrepreneurs’ optimal selling prices, service level, and wholesale prices in the newly launched period and markdown period are, respectively , , , and and the manufacturer’s total profit in the two periods is .

The retailer’s total profit is .

5. Analysis

5.1. Fashion Utility Impact

This section studied how fashion utility affects optimal pricing during launch, markdown periods, and service level-setting problems.

Firstly, we analyzed how the fashion utility affects the retail prices in both online and offline channels during the launch period.

Lemma 1.

(1) The monotonicity of the equilibrium retail price in the online channel with respect to fashion utility is, respectively: , , , .

(2) The monotonicity of the equilibrium retail price in the offline channel with respect to fashion utility is, respectively: , , , .

Lemma 1 shows that during the launch period, retail prices in both online and offline channels increase with the fashion utility of the product. This is intuitive, as higher fashion utility enhances consumers’ perceived value, thereby increasing their willingness to pay. Consequently, manufacturers can capitalize on this by setting higher retail prices across channels to maximize profits during the launch phase. From a cost perspective, the ability to produce high-fashion products often requires designers with strong aesthetic sensibilities, which correlates with higher human resource costs. As a result, brands tend to charge premium prices to maintain adequate gross margins. Additionally, creativity itself represents a form of intellectual capital that warrants an appropriate return. Louis Vuitton, a luxury brand that sells primarily through offline boutiques and now develops its online channel, should set high prices for its products during the launch period.

Then, we compared the equilibrium offline prices in four strategies and had:

Proposition 5.

. When managing the offline channel, the manufacturer must maintain uniform pricing across all offline stores. However, the retailer will price it comparatively higher.

This may be because the retailer’s cost (in the meanwhile, the wholesale price of the manufacturer) is greater than that of the manufacturer, determined by . Notably, after we analyzed the profit the manufacturer gets from managing the offline stores and that of the retailer, the result is yielded as , . Noticed that . Although the retailer sets higher retail prices, it earns only half the manufacturer’s profit. When launching new garments, GAP should maintain uniform pricing across its directly operated stores to ensure consistent brand positioning and reinforce consumer trust. However, partner retailers independently determine pricing in their stores, frequently setting premium rates—a differential particularly evident with collectible sports merchandise like official football jerseys. For instance, while AC Milan jerseys at San Siro Stadium (Milan) and Bayern Munich kits at Allianz Arena (Munich) sell at manufacturer-set standard prices, identical merchandise through international third-party retailers in markets like Singapore commands significantly higher prices.

Then, we studied how the fashion utility affects retail and wholesale prices during the markdown period.

Lemma 2.

(1) The monotonicity of equilibrium retail price in the online channel during the markdown period with respect to the fashion utility is, respectively: , , , .

(2) The monotonicity of the equilibrium wholesale price in the online channel during the markdown period with respect to the fashion utility is , .

Unlike the conclusion obtained from Lemma 1, Lemma 2 shows that the online retail and wholesale price decreases with the fashion utility during the markdown period. The more fashion utility the product is conceived with, the lower the price during the markdown period. This may be due to the fast speed of fashion trend changes. Consumers do not perceive fashion utility when the product is out of season. As a result, consumers are less willing to pay a premium, and the manufacturer is incentivized to lower prices in order to stimulate demand and clear inventory. This pricing behavior can be observed in practice. GAP, as a mainstream fashion brand, should adopt relatively low prices at the end of each season. As consumer perception of fashion utility declines, so does their willingness to pay, prompting the brand to discount products during the markdown phase in order to prepare for the next collection. Consequently, promotional pricing is employed to accelerate inventory turnover during this period.

We further explored the fashion utility’s impact on the service level.

Lemma 3.

The monotonicity of the equilibrium service level concerning the fashion utility is, respectively: , , , .

Lemma 3 shows that the service level (whether it is the manufacturer or the retailer providing the service) increases concerning the fashion utility, as the higher the fashion utility, the higher the service level. For fashion brands, consumers have a higher demand for the all-around consumer experience. Especially for products with high fashion utility, which are more recognizable and unique, when consumers buy fashion products, they are more concerned about the experience they get when purchasing the product. To meet consumers’ needs, brands should provide quality services, such as efficient pre-sales consultation, fast logistics, and perfect after-sales service, to improve consumers’ purchasing experience and enhance their brand identity. Moreover, high-fashion brands often extend their service expectations beyond the consumer interface to include their service providers. As the perceived fashion utility of a product increases, so too does the brand’s emphasis on service consistency and symbolic value throughout the supply chain. Coach offers customers in-store embossing services that allow for the personalization of leather tags. These customizations not only enhance the emotional value of the product but also elevate its perceived fashion utility by emphasizing individuality and exclusivity. This illustrates how service augmentation can serve as a strategic response to the ephemeral nature of fashion-oriented products, helping to sustain consumer interest over shorter product life cycles.

When we studied and compared service levels in four strategies, we obtained:

Proposition 6.

When managing offline channels, the manufacturer must maintain standard service in physical stores, while the retailer provides comparatively inferior service.

This might be because, compared to the professional retailers of fashion brands, manufacturers are required to provide high-quality and standardized customer service in order to maintain their premium brand image. It is especially true in luxury products. Luxury brand boutiques typically offer better service because their services can focus more on a specific brand’s customer base, resulting in more personalized and refined service. For multinational fashion companies, this imperative is further reinforced by stringent compliance protocols and standardized operating procedures (SOPs) designed to ensure consistency across global operations. Louis Vuitton’s boutiques usually offer more professional and customized services. Their sales will be highly trained and familiar with the brand’s history, product materials, and production techniques and can provide customers with professional advice and matching solutions. They will also pay more attention to customer relationships, understand their preferences and needs, and provide personalized service and courtesy. In addition, Louis Vuitton, as a luxury fashion manufacturer and retailer, implements rigorous guidelines for both in-store service and third-party logistics. Its white-glove delivery services, uniform packaging standards, and post-sale customer care all reflect a tightly controlled brand experience. These practices are not only part of image management but also essential to meeting internal quality audits and global compliance expectations, especially when operating in diverse markets with varying local service conditions.

5.2. Channel Strategy Analysis

In this section, we studied how the manufacturer implements channel strategy, accounting for the changes in the fashion utility of the fashion product during the launch and markdown periods. We divided it into two main situations: (1) The manufacturer outsourcing by the whole channel. (2) The manufacturer outsourcing by the selling period.

To study the first situation, firstly, we considered the manufacturer entrusting the retailer with the offline channel (RM) and compared the benefits with the MM strategy, and then we studied the condition of the RM strategy. Then, we also analyzed the situation when the manufacturer should outsource the online channel (RR).

We analyzed whether the manufacturer should outsource the offline channel. So, we compared the condition of the manufacturer operating both channels and the condition of outsourcing the offline channel. We obtained that from Proposition 1 and Proposition 4:

Proposition 7.

In any case, .

Proposition 7 addresses whether a manufacturer should delegate offline distribution to the retailer while operating online channels. The study demonstrates that the manufacturer managing online channels should directly operate offline channels during launch periods. This outcome may be explained by the advantages of direct offline sales, which offer consumers more personalized shopping experience, immediate customer service, and after-sales support. In physical stores, consumers can engage directly with trained staff for product information, size recommendations, and usage guidance. Managing both online and offline channels allows the manufacturer to better target high-value customers and leverage cross-channel synergies. Additionally, in-store promotions can enhance brand visibility and reinforce brand identity, indirectly boosting online sales. Therefore, when the manufacturer possesses an online channel, it is not optimal to outsource offline distribution to the retailer—particularly during the launch phase. This insight aligns with real-world practices. Nike has a strong online sales channel worldwide, but it still needs to attach importance to the strategy of direct sales through offline channels during the launch period.

As the manufacturer should not outsource the offline channel, we studied in which condition the manufacturer should entrust the retailer with the online channel. We compared the situation of the manufacturer managing both channels and the situation of entrusting the retailer to operate the online channel and obtained:

Proposition 8.

When , . Where , , , .

Proposition 8 answers whether the manufacturer should entrust the retailer to sell the product online under the premise of owning the traditional offline channel. We find that when , the manufacturer should sell directly on the online channel; when , the manufacturer can entrust the retailer. This might be related to the proportion of leisure-oriented strategy consumers in the market and the magnitude of the product’s fashionable attributes. Since leisure-oriented strategy consumers tend to purchase fashion products online, the higher their proportion in the market, the more products the manufacturer can sell through online channels and the greater profits they can obtain. Then, the manufacturer should not entrust the retailer to sell the product online. Conversely, if the proportion of leisure-oriented strategy consumers is relatively small, and the online channel becomes less profitable and is mainly used for product promotion, then the manufacturer should hand over the online channel to the retailer. As a brick-and-mortar retailer, ZARA has its branded stores worldwide, interacting with consumers through direct sales. However, in the face of the growing e-commerce market, ZARA should entrust retailers with online channels. ZARA can partner with well-known e-commerce platforms, such as Amazon, Zalando, and T-mall, to sell its online product line. This allows ZARA to focus on product design and brand marketing and leave the operational work, such as online sales and logistics, to professional e-commerce platforms.

Then, we analyzed the situation of the manufacturer outsourcing by the selling periods. The fashion product will quickly lose its attraction to the market when it becomes out of season or out of date. Thus, brands always attach importance and choose to manage the new launch periods while handing the products to the retailer during the markdown periods. So, we compared the MM strategy and MR strategy here and found:

Proposition 9.

When , .

Noticed whether the manufacturer handover in the markdown period depends on the fashion utility . When the fashion utility is high, the manufacturer should sell directly during the markdown period. Otherwise, the manufacturer can entrust the retailer to sell instead. This might be because if the product has a high fashion value, during the markdown period, it will attract more price-sensitive consumers who did not purchase it during the product’s launch period. Therefore, direct sales can maximize market opportunities and profits when fashion utility is high. The manufacturer can control their products’ pricing, sales strategy, and brand image through direct marketing to better meet consumer expectations and needs. In addition, direct marketing can also help the manufacturer to build closer relationships with consumers, gather feedback and market information, and provide valuable guidance for future product development and marketing strategies. Gucci, for example, retailers have more robust distribution networks and advertising channels. They can attract consumer attention through various promotions to clear inventory and increase sales. However, if the fashion utility is relatively low, and it will decrease over time, for example, due to seasonal changes, changing trends, or shifting consumer demand. In such cases, the manufacturer should cooperate with the retailer. Manufacturers can delegate inventory and sales management to retailers to ensure products are sold quickly and reduce inventory backlogs.

6. Numerical Examples

Here, numerical analyses are employed to investigate further how the fashion utility affect the prices of the product in different periods and through different channels, as well as the profits of the manufacturer. To analyze this question more comprehensively, referring to He et al. [16], Qiu et al. [27], Lin et al. [32], and Chen et al. [38], we set the basic parameters as follows: , , , .

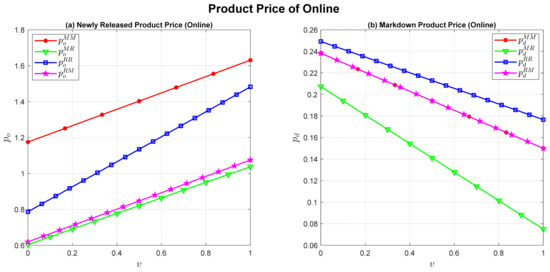

6.1. Impact of on Product Selling Prices and Wholesale Prices

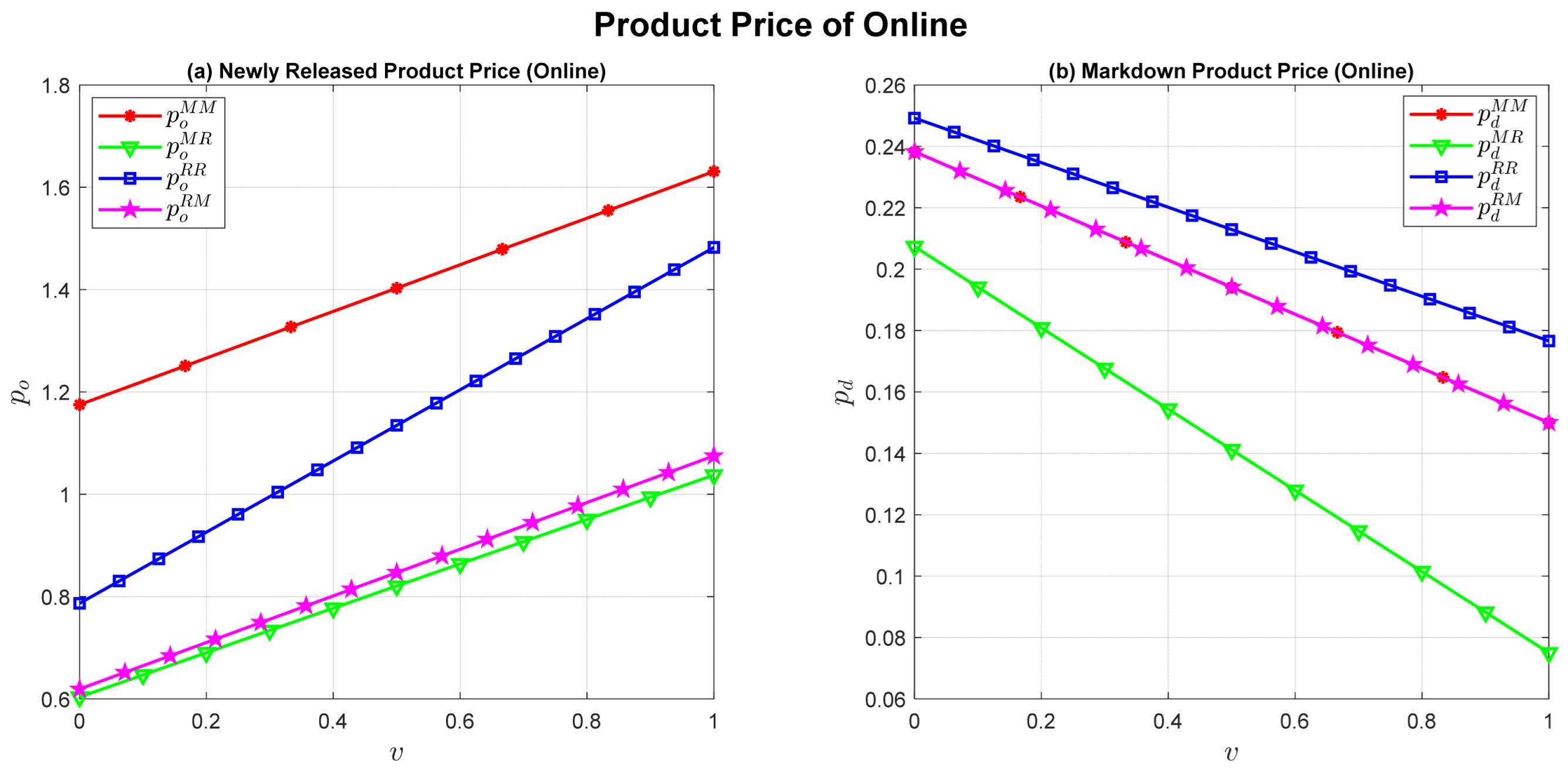

We analyzed how the fashion utility affect the product’s selling price of the online channel in both the launch period () and markdown period () under four strategies. The numerical analysis results are shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6.

The Product’s Selling Price of Online Channel.

From Figure 6, the product’s selling price of the online channel in the launch period is positively proportional to the fashion utility , while during the markdown period, the product’s selling price of the online channel is negatively correlated with it. This further validates the conclusions obtained from Lemma 1 and Lemma 2. We can also observe that when the fashion value is determined, the product’s selling prices in the markdown period are much lower than those in the launch period under the four strategies. And the larger the value is, the greater the price difference will be. This observation aligns with both theoretical predictions and industry practices. Consider ZARAs new product launches: Seasonal designs like influencer-popularized pleated dresses generate high fashion utility, commanding uniform pricing (e.g., ¥599 on official channels) that drives approximately 70 percent sell-through during initial distribution. The subsequent markdown phase transitions remaining inventory to online outlets, where time-based markdowns apply differential depreciation. Basic items typically reduce to ¥299 (50% discount), while high-fashion-utility pieces—such as the 2023 Studio collection—undergo accelerated depreciation due to seasonality, reaching final clearance prices as low as ¥199 (67% discount).

In addition, from Figure 6, an interesting pattern emerges: under the RM strategy, the product’s selling price in the online channel is the lowest across both periods, whereas the MM and RR strategies exhibit relatively higher online prices. This may be attributed to the fact that when either the manufacturer (in MM) or the retailer (in RR) maintains control over the online channel throughout both periods, they are incentivized to set higher prices in order to maximize profits.

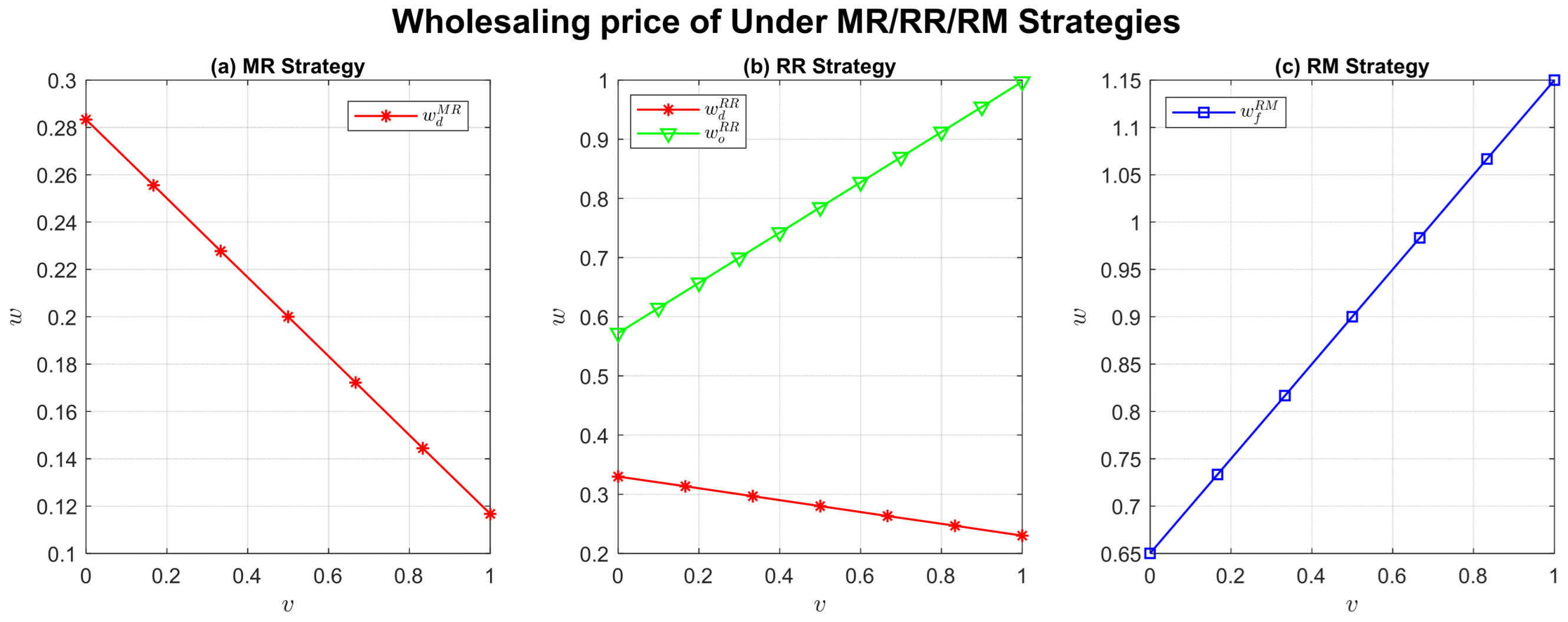

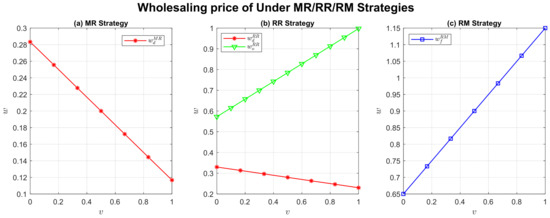

Next, we analyzed how the fashion utility affect the wholesale price under the MR strategy, the RR strategy, and the RM strategy. The numerical analysis results are shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7.

The Wholesale Price of Online and Offline Channels.

From Figure 7, during the launch period, the wholesale prices for both online and offline channels are positively proportional to the fashion utility , and negatively correlated with it in the markdown period. This is consistent with lemma 2. The wholesale price during the launch period is consistently higher than that in the markdown period, which aligns with practical industry practices. Furthermore, several noteworthy patterns emerge: during the markdown period, the wholesale price under the MR strategy is lower than that under the RR strategy, and during the launch period, the wholesale price under the RR strategy is lower than that under the RM strategy. These findings can be explained as follows: When outsourcing the online channel to the retailer during the markdown period (MR strategy), the manufacturer is motivated to offer lower wholesale prices to accelerate out-of-season inventory clearance. In contrast, when the retailer controls the online channel across both periods (RR strategy) or the offline channel during the launch period (RM strategy), it accesses a broader segment of business-oriented consumers with lower price sensitivity. In these cases, the manufacturer has greater pricing power and can set higher wholesale prices to maximize profit.

6.2. Impact of , and on Manufacturer’s Best Channel Strategy

Here, numerical analyses are employed to investigate further how the fashion utility , the off-season discount and the proportion of the leisure strategic consumers in the market affect the manufacturer’s profit. We study its impact on channel choice by changing a specific parameter.

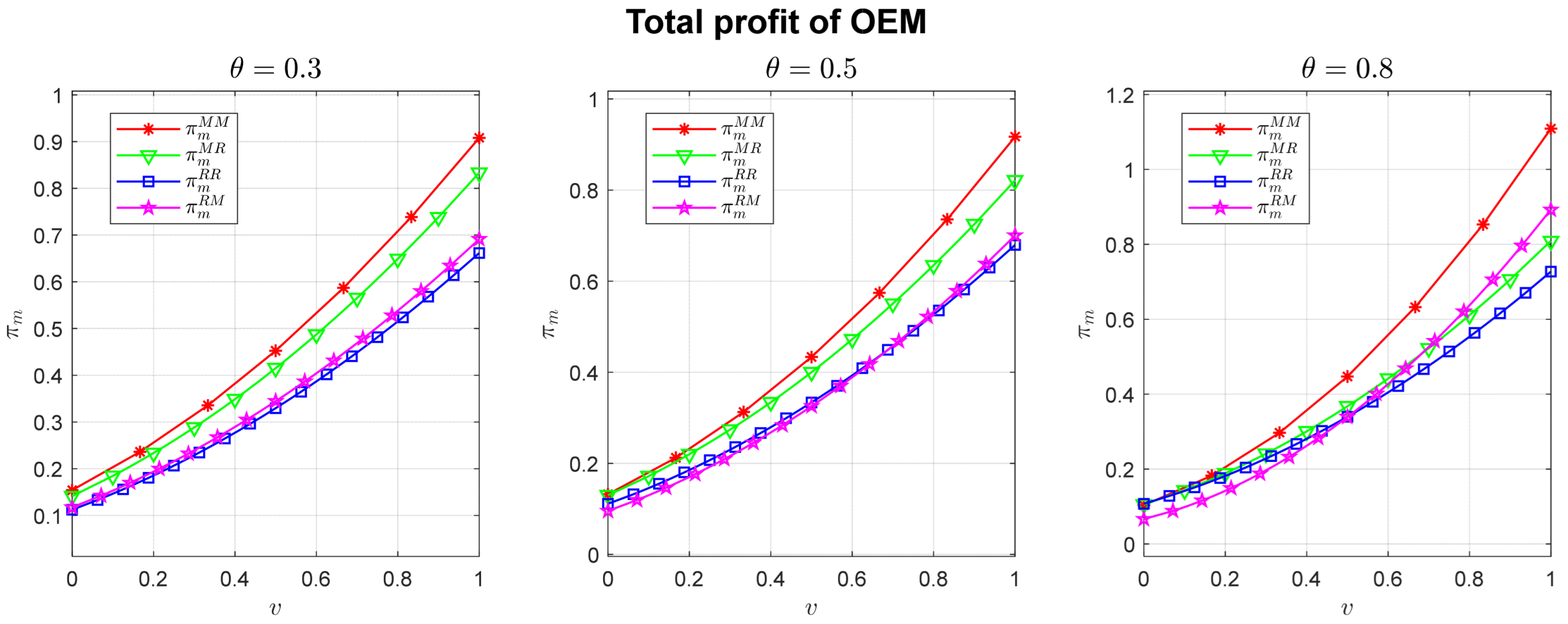

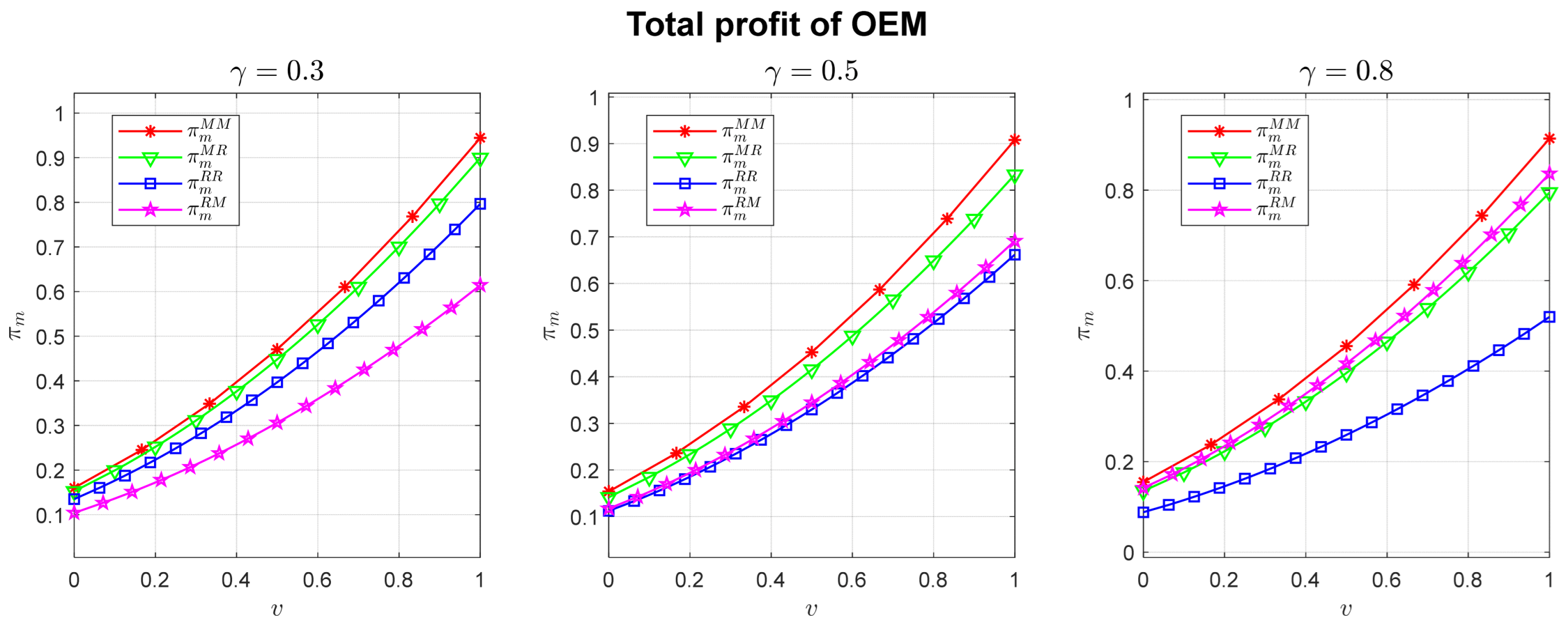

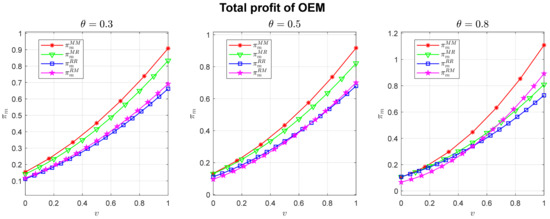

Firstly, we change the as 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, and keep the rest of the parameters as , , . The numerical analysis results are shown in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8.

The Manufacturer’s Profit When Changing .

From Figure 8, the following conclusions can be drawn: When off-season discounts are small—indicating low utility retention during the markdown period—it is optimal for the manufacturer to adopt a full dual-channel sales strategy throughout both periods (MM strategy). However, when off-season discounts are substantial—reflecting the continued relevance of functional utility during the markdown phase—the optimal channel strategy depends on the level of fashion utility. If fashion utility is low, the manufacturer should operate offline sales during the launch period while entrusting the retailer with online distribution throughout both periods (RR strategy). Conversely, if fashion utility remains high, a direct dual-channel strategy across both periods (MM strategy) is recommended. Off-White’s limited-edition sweatshirts retain high collectible value, prompting manufacturers to maintain full pricing authority throughout their lifecycle—exclusively through official channels. Even during markdowns, discounts remain modest (20%) and member-exclusive. This strategy prevents third-party price erosion, preserves perceived scarcity, and maximizes fashion premiums. Conversely, Loro Piana’s classic cashmere coats—while luxurious—lack comparable trend-driven appeal. Their limited markdowns (15%) reflect stable market positioning without urgency. To protect brand equity, the manufacturer employs full-cycle direct sales via flagship channels, strictly controlling discounts. This approach mitigates brand devaluation risks from outsourced retailers’ deep discounts (e.g., 30%) during inventory liquidation, sustaining profitability and premium positioning despite lower turnover efficiency.

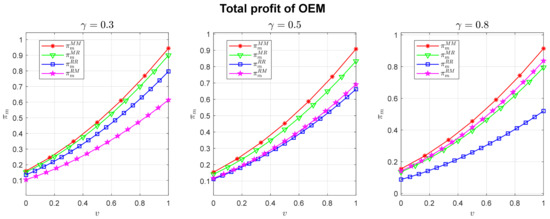

Then, we change the as 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, and keep the rest of the parameters as: , , . The numerical analysis results are shown in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

The Manufacturer’s Profit When Changing .

From Figure 9, the following conclusions can be drawn: When the proportion of leisure consumers increases, the manufacturer’s profit exhibits fluctuations under the direct sales strategy across both online and offline channels (MM strategy). Still, the impact is small, and the MM strategy is always the optimal strategy for the manufacturer. It is worth mentioning that if the manufacturer considers completely outsourcing the sales of either the launch period or the markdown period to the retailer, then when the proportion of leisure consumers in the market is relatively small, the manufacturer-managed offline channel (RR strategy) will bring more profits to the manufacturer, but when the proportion is high, the manufacturer-managed online channel (RM strategy) is better.

6.3. Strategy Analysis

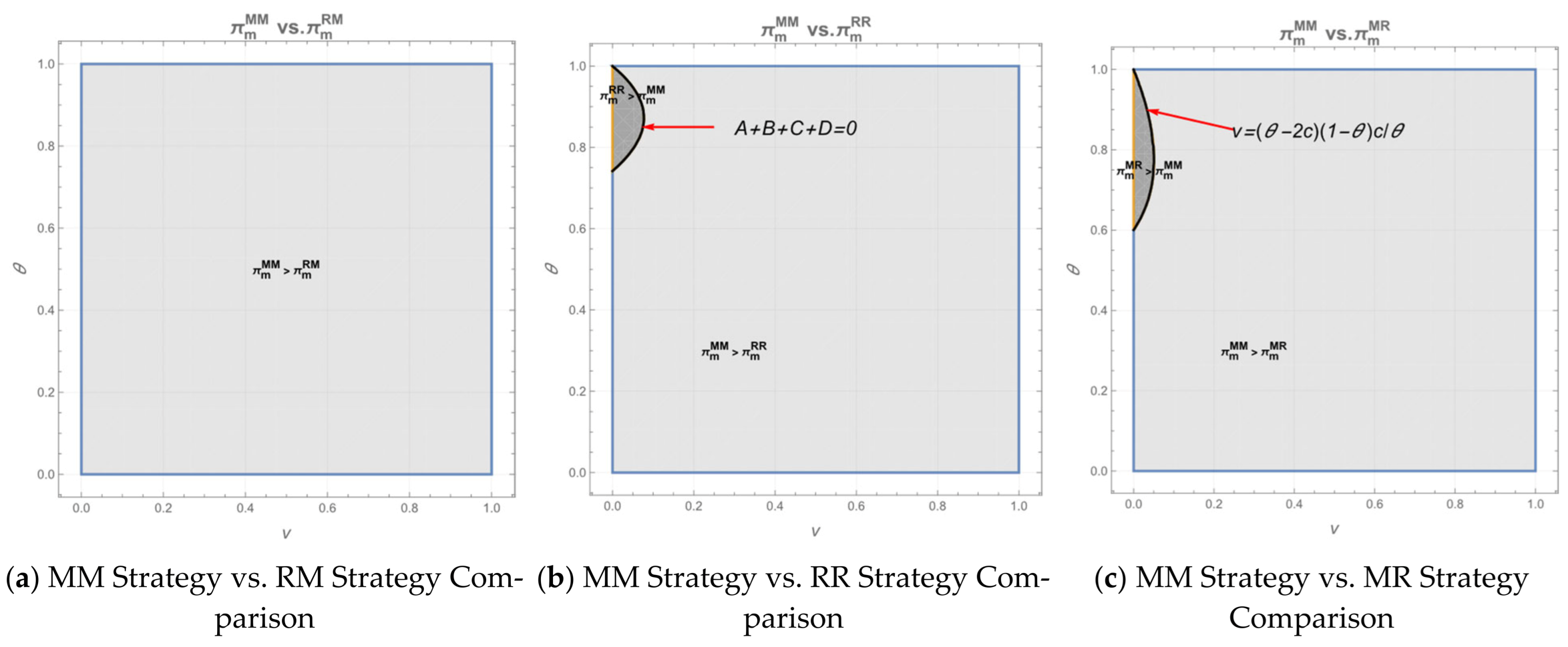

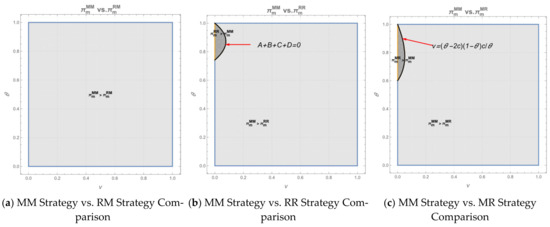

We analyzed how the fashion utility and off-season discount influence the manufacturer’s choice of sales channel strategies across both launch and markdown periods. The strategy analysis results are shown in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10.

Manufacturer’s Choice of Sales Channel Strategies.

From Figure 10a, in any case, , which is consistent with Proposition 7. When manufacturers operate online channels during both launch and markdown periods, they should directly manage offline channels rather than cede control to retailers—regardless of off-season discounts or fashion value. The core rationale is that centralized manufacturer management enables effective omni-channel coordination, prevents channel conflicts, and ensures uniform pricing, standardized brand presentation, and consistent promotional timing, thereby maximizing brand value and profitability. UNIQLO synchronizes new product launch timing, pricing, and promotions across its global direct-operated stores and online channels. This practice demonstrates the strategic advantages of manufacturer-led offline channel management during product launches.

Subsequently, we analyzed the conditions under which manufacturers should delegate online channel operations to retailers. Figure 10b reveals whether manufacturers should delegate online channels across both periods, while Figure 10c illustrates scenarios where delegation occurs exclusively during markdown periods. Figure 10b demonstrates that when , manufacturers should retain full control of all channels. Otherwise, they should delegate online operations to retailers during both launch and markdown periods. This strategic distinction stems from how different consumer segments engage with channels and contribute to manufacturer profitability. Specifically, markets with a higher proportion of leisure-oriented consumers exhibit greater direct sales potential and profit margins through manufacturer-operated online channels. Thus, manufacturers should maintain direct control in such contexts. This principle is exemplified by ZARA and H&M, whose core demographics include trend-sensitive, price-conscious youth. Both brands invest heavily in owned digital platforms (direct-to-consumer models) and rarely delegate seasonal new releases or core online sales to third-party retailers. Conversely, when leisure-oriented consumers represent a smaller segment, online channels primarily serve brand-building functions such as product visibility and offline traffic generation. Here, delegating operations to retailers with established traffic and expertise reduces operational costs while enhancing market coverage and promotional effectiveness—thereby strengthening online-offline synergy.

Figure 10c indicates that when , manufacturers should retain full channel control. Conversely, during markdown periods, online channel operations should be delegated to retailers. Unlike the scenario in Figure 10b, this distinction arises from unique consumer behaviors surrounding high-fashion-value products during markdowns. Products with high fashion value (e.g., limited editions, avant-garde designs) strongly stimulate purchasing among price-sensitive consumers—particularly prospective buyers deterred by launch prices. Manufacturer-direct sales enable precise control over discount pacing and inventory allocation, preventing retailer over-discounting that erodes brand premium. A-Cold-Wall* × Nike collaborations, whose high-fashion releases consistently trigger purchase frenzies. The brands not only control launch channels but also maintain direct markdown sales (e.g., Nike’s “Archive Sale” platform). This ensures moderate discounting (e.g., 30% vs. 50%) for scarce items. Conversely, low-fashion-attribute products (e.g., basic tees, standard knitwear) generate limited off-season appeal. Delegating surplus inventory clearance to high-traffic retailers reduces operating costs while accessing long-tail markets through their distribution networks. Calvin Klein’s approach to basic underwear lines illustrates this: during markdowns, the brand typically delegates online clearance to discount retailers like Amazon and TJ Maxx. Minimal product differentiation and consumer price sensitivity eliminate the need for costly direct sales infrastructure.

7. Conclusions

This paper examines how the fashion product manufacturer sets channel strategy considering the strategic consumers. To this end, we construct a supply chain model that includes a manufacturer (like Nike, Adidas, LV, Coach, GAP, Bridge, etc.) as the Stackelberg leader and a retailer (like Alibaba, Footlocker, etc.) as the follower, facing business and leisure strategic consumers with different preferences for functional and fashion utilities of fashion products. This paper assumes that the manufacturer can either sell their fashion products wholesale to retailers or directly to consumers through online and offline channels, and both players make decentralized decisions to maximize their profits. We conducted a detailed study on four different marketing channel strategies (the MM strategy, the MR strategy, the RR strategy, and the RM strategy). The main practical insights of this work are as follows:

Firstly, the manufacturer should adopt the MM strategy when the off-season discount is small. This is typical for luxury or high-end fashion brands with minimal seasonal markdowns. Louis Vuitton rarely engages in heavy discounting and should operate through its own stores and official website, allowing it to maintain strict control over both pricing and brand image. However, when off-season discounts are substantial—such as in fast fashion or mid-tier brands—the channel strategy must be adapted based on the product’s fashion utility. If the fashion utility is low, meaning the product is primarily functional by the time it enters the markdown period, the RR strategy is often more effective. In this case, the manufacturer manages only offline full-price sales during the launch period, while retailers handle the online markdown period. A sportswear brand like Puma can release a new sneaker through flagship stores during launch but should rely on retailers like Amazon Fashion to handle clearance sales online. If the fashion utility is significant, the MM strategy should be adopted. Nike’s Air Jordan line retains significant symbolic value, even with discounted or retro releases. Consequently, Nike should distribute these products exclusively through its own digital platform and select retail partners under tightly controlled conditions.

Secondly, the higher the fashion utility, the higher the retailing price, wholesale price, and service level of both online and offline channels during the launch period; the lower the retail price and the wholesale price during the markdown period. Moreover, the manufacturer’s wholesale price positively correlates with manufacturing costs. During the launch period, Coach releases its seasonal collections—such as handbags or leather accessories—at relatively high retail prices through both its own stores and official online platform. The elevated price point and service level, including customized monogramming and premium packaging, reflect the product’s fashion utility and the brand’s effort to create emotional and symbolic value for consumers. However, as the season progresses and fashion relevance declines, the same or similar products often enter the markdown phase via Coach Outlet stores or online discount platforms. These markdown prices can be substantially lower—sometimes reduced by 30–60%—highlighting the drop in perceived fashion value. This pricing strategy allows the brand to recover value from remaining inventory while catering to a more price-sensitive customer segment. Meanwhile, the wholesale price charged to authorized retailers during the launch phase is positively correlated with the product’s manufacturing cost, which includes material quality, leather craftsmanship, and branding.

In addition, when the proportion of leisure consumers increases, the manufacturer’s profit fluctuates when adopting the two-channel, two-stage, complete direct sales strategy (MM strategy). Still, the change is small, and the MM strategy remains the optimal strategy for the manufacturer. However, it is worth mentioning that when the proportion of leisure consumers in the market increases, the manufacturer’s profit changes more in the RM scenario, and the profit rises with the proportion of leisure consumers.

Finally, when managing offline channels, the manufacturer must maintain both uniform pricing and standard service in brick-and-mortar stores during the launch period, irrespective of channel strategy. Lululemon operates its own brick-and-mortar stores globally and provides high-touch services such as personalized fittings and product education, while strictly adhering to standardized pricing across its network. Additionally, when managing offline stores, the retailer provides substandard service but implements elevated pricing compared to the manufacturer. Nike products sold at Foot Locker, although prices are often similar to Nike’s own stores during launch, Foot Locker may lack the same level of brand-focused service, product storytelling, or immersive in-store experience that Nike delivers through its flagship locations.

In conclusion, our work provides several theoretical contributions and supplements the research on fashion products, strategic consumers, and multi-channel strategy. Moreover, the interesting research findings and valuable managerial insights obtained in this paper can offer suggestions for the production and sales strategies of enterprises. However, our paper also has its limitations. For instance, we assume that the fashion product manufacturer is always involved in the sales process, without considering the scenario in which the manufacturer completely delegates the sales to the retailer across both online and offline channels. Moreover, we do not account for the influence of information channels such as social media on the purchasing behavior of strategic consumers. Therefore, further research can extend the line of the present study in several directions. First, it can be assumed that the manufacturer does not participate in sales. Subsequent research can consider the scenario where the manufacturer entrusts the retailer to sell on commission in a two-stage omni-channel framework. Second, given the characteristics of fashion products, future studies may consider competition between online and offline channels and demand transfer between them. Additionally, it is possible to extend the multi-channel to the omni-channel by considering the impact of the social media selling channel on the manufacturer’s profit.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13162575/s1. File S1: The complete derivations/proofs for this thesis are provided in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, model construction, and analysis were performed by L.L., X.L. and S.Z. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S.Z., L.L., X.L. and M.W., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China grant number 23CGL020.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors of this article have reviewed the final version and approved it for publication. We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alom, S.; Basu, S.; Basu, P.; Joshi, R. Shipment policy and its impact on coordination of a fashion supply chain under production uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 192, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Ibar, M.; Nylund, P.A.; Brem, A. Circular business models in the luxury fashion industry: Toward an ecosystemic dominant design? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 37, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemi, Y.; Ozuem, W.; Wiid, R.; Hobson, A. Luxury fashion brand customers’ perceptions of mobile marketing: Evidence of multiple communications and marketing channels. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadayi-Usta, S. A novel neutrosophical approach in stakeholder analysis for sustainable fashion supply chains. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 370–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, U.J.; Kim, J.H. Financial productivity issues of offshore and “Made-in-USA” through reshoring. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Xu, X.Y.; Choi, T.M.; Shen, B. Will the presence of ‘fashion knockoffs’ benefit the original-designer-label product supply chain? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 62, 1541–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Li, L. Fashion consumption of naturally dyed products: A cross-cultural study of the consumption of blue-dyed apparel between China and Japan. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2023, 31, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.; Sen, C.G.; Isik, E.E. A Hyper-Personalized Product Recommendation System Focused on Customer Segmentation: An Application in the Fashion Retail Industry. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, Y. Cross-channel spillover effect of price promotion in fashion. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Rothenberg, L.; Xu, Y.J. Young luxury fashion consumers’ preferences in multi-channel environment. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullak, F.S.; Baier, D.; Woratschek, H. How do customers meet their needs in in-store and online fashion shopping? A comparative study based on the jobs-to-be-done theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Lee, Y.S. A Study on the Impact of the Consumption Value of Sustainable Fashion Products on Purchase Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.F.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, Y.L. Intertemporal service pricing with strategic customers. Oper. Res. Lett. 2009, 37, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, Y.-W.; Hu, X.-J.; Yang, A.-F. Quality disclosure in the presence of strategic consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Xia, L.J. Launch strategies for luxury fashion products in dual-channel distributions: Impacts of social influences. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; He, Y.; Zhou, L. Channel strategies for dual-channel firms to counter strategic consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, J.L.; Cheng, T.C.E. Supply Chain Coordination Facing Boundedly Rational Strategic Customers. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 3688–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, C.H.; Zhang, M. Manufacturer’s decision-making and coordination strategy in an asymmetric multi-channel environment. Rairo-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 2167–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Y. The Mutual Impact of Suppliers’ Online Sales Channel Choices and Platform Credit Decisions for Offline Channels. Mathematics 2025, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backs, S.; Jahnke, H.; Lupke, L.; Stucken, M.; Stummer, C. Traditional versus fast fashion supply chains in the apparel industry: An agent-based simulation approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 305, 487–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, A.; Soysal, G.P.; Ratchford, B.T. Alleviating demand uncertainty for seasonal goods: An analysis of attribute-based markdown policy for fashion retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.J.; Ko, E.J.; Borenstein, B.E. The interaction effect of fashion retailer categories on sustainable labels: The role of perceived benefits, ambiguity, trust, and purchase intention. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 1016–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.O.; Cho, S.Y.; Yoo, J.; Yun, S.B. Mathematical modeling of trend cycle: Fad, fashion and classic. Phys. D-Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 472, 134500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.H.; Yan, L.T. Dynamic Pricing and Inventory Strategies for Fashion Products Using Stochastic Fashion Level Function. Axioms 2024, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Cho, H.Y. Navigating impressions: The impact of luxury social media posts. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2025, 29, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.M. Intertemporal pricing with strategic customer behavior. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.C.; Sun, M.H. Dynamic pricing and quick response of a retailer in the presence of strategic consumers: A distributionally robust optimization approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 307, 1270–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Yang, Z.R.; Wang, Z.R.; Sun, W.W. Contextual Dynamic Pricing with Strategic Buyers. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2025, 120, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Workman, J.E. Online Shopping Attitudes, Need for Touch, and Interdependent Self-Construal among Korean College Students. Korea Obs. 2023, 54, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J.E.; Lee, S.H. Fashion trendsetting, attitudes toward money, and tendency to regret. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 1203–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Park, J.; Lee, J.C. The effect of shopping channel (online vs. offline) on consumer decision process and firm’s marketing strategy. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ma, X.; Talluri, S.; Yang, C.H. Retail channel management decisions under collusion. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; He, J. Online customized strategy for manufacturers to counter showrooming behavior in a dual-channel supply chain. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2024, 35, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shao, J.; Liang, L.P.; Tang, Y. Multi-channel retailing and consumers’ environmental consciousness. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025, 345, 467–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswaran, L.; Cho, S.H.; Scheller-Wolf, A. Consumer Return Policies in Omnichannel Operations. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 5558–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Giri, R.N. Consumers’ purchasing decisions of a dual-channel supply chain system under return and warranty policies. Int. J. Syst. Sci.-Oper. Logist. 2023, 10, 2173990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageswaran, L.; Hwang, E.H.; Cho, S.H. Offline Returns for Online Retailers via Partnership. Manag. Sci. 2025, 71, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, Q.; Wang, W.J. Optimal Policies for the Pricing and Replenishment of Fashion Apparel considering the Effect of Fashion Level. Complexity 2019, 2019, 9253605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).