Abstract

We introduce I-fp convergence (ideal convergence in fuzzy paranormed spaces) and develop its core theory, including stability results and an equivalence to -fp convergence under the AP Property. Building on this foundation, we design an adaptive base-stock policy for a single-echelon inventory system in which weekly demand is expressed as triangular fuzzy numbers while holiday or promotion weeks are treated as ideal-small anomalies. The policy is updated by a simple learning rule that can be implemented in any spreadsheet, requires no optimisation software, and remains insensitive to tuning choices. Extensive simulation confirms that the method simultaneously lowers cost, reduces average inventory and raises service level relative to a crisp benchmark, all while filtering sparse demand spikes in a principled way. These findings position I-fp convergence as a lightweight yet rigorous tool for blending linguistic uncertainty with anomaly-aware decision making in supply-chain analytics.

Keywords:

adaptive base-stock policy; approximation property; fuzzy paranormed space; ideal convergence; I-fp convergence; inventory optimisation; Monte Carlo simulation; supply chain resilience; triangular fuzzy demand; uncertainty modelling MSC:

40A35; 46S40; 90B05

1. Introduction

Statistical convergence generalizes the usual limit of a sequence by requiring convergence on a set of indices of natural density one. This notion was introduced in the 1950s by H. Fast and S. Steinhaus [1,2] and has since found many applications in analysis. A further generalization is ideal convergence, in which the set of “negligible” indices is prescribed by an ideal on the natural numbers. Kostyrko et al. [3] formalized I-convergence of sequences in metric spaces, where an admissible ideal replaces the role of density-one sets. I-convergence extends both statistical convergence and ordinary convergence, and it has been widely studied in summability theory, number theory and optimization.

Parallel to these developments, fuzzy analogues of normed spaces have been developed. Katsaras [4] was among the first to introduce a fuzzy seminorm (and hence a fuzzy norm) on a linear space. Later, Felbin [5] gave an alternate formulation of a fuzzy norm, and Bag and Samanta [6] systematically studied continuity and boundedness in fuzzy normed spaces. In these frameworks, the “length” of a vector is not a real number but a fuzzy set (often a fuzzy number), allowing uncertainty to be modelled in functional analysis [7].

Ideal and summability techniques were then imported: Hazarika and Savaş [8] examined I-limits and -summability in difference sequence spaces of fuzzy numbers, while Hazarika [9] provided a systematic treatment of I, and I-Cauchy convergence for sequences and double sequences in fuzzy normed settings. The framework was pushed further when Rashid and Kočinac [10] developed ideal convergence and cluster theory in 2-fuzzy 2-normed spaces, and subsequent work by Dündar, Türkmen and collaborators [11,12,13] extended these concepts to double sequences and lacunary behaviour.

Alongside fuzzy norms, one can consider paranormed spaces. Early work by Simons [14] and Maddox [15] generalized classical sequence spaces by introducing suitable paranorms. Only recently has the idea of a fuzzy paranormed space been introduced. In particular, Çınar et al. [16] defined a fuzzy paranorm and a fuzzy paranormed space, showing that this setting had not been treated in the literature. They also studied convergence and Cauchy sequences in such spaces, emphasizing that fuzzy paranormed spaces generalize both fuzzy normed spaces and classical paranormed spaces.

Despite these advances, the combination of ideal convergence and fuzzy paranormed spaces appears to be unexplored. In other words, while Kostyrko et al. [3] showed how I-convergence works in metric (and normed) settings, and Çınar et al. [16] recently introduced fuzzy paranormed spaces, no previous work has defined I-convergence in a fuzzy paranormed space. This represents a gap in the literature. The present paper fills this gap by introducing I-fp convergence (ideal convergence in fuzzy paranormed spaces) and developing its basic theory. We prove the fundamental properties of I-fp convergent and I-fp Cauchy sequences, analogous to those in ordinary and fuzzy settings.

1.1. Recent Robust Base-Stock Research

Contemporary studies revisit base-stock policies through a robust-optimization lens. Gijsbrechts et al. [17] introduce a look-ahead peak-shaving rule that balances capacity with non-stationary demand under volume flexibility. For multisource systems, Xie et al. [18] prove that the optimal rolling-horizon strategy is a dual-index base-stock policy. A broad comparative survey by Zhang et al. [19] identifies base-stock triggers as the most transferable decision rule across robust formulations. Finally, Öğünmez and Türkmen [20] link fuzzy paranormed convergence tools with adaptive inventory control under demand shocks, underscoring the compatibility of base-stock logic with linguistic uncertainty—an angle further developed in the present study.

1.2. Key Technical Contributions

Collectively, the work offers a mixed theoretical–practical contribution.

- (C1)

- Theory: We formalise I-fp convergence in fuzzy paranormed spaces and establish its basic limit and Cauchy properties (Section 3).

- (C2)

- Equivalence: We prove that I-fp and -fp converge coincide under the AP Property, extending Kostyrko’s framework to the fuzzy realm.

- (C3)

- Algorithm: We embed the theory in a spreadsheet-implementable, learning base-stock policy that filters anomaly weeks via an ideal (Section 4).

- (C4)

- Impact: Monte-Carlo evidence shows 31% cost reduction and ≈7 pp service-level gains over a crisp benchmark without tuning effort (Section 5).

To illustrate the relevance of I-fp convergence, we construct a theoretical inventory optimization model with triangular fuzzy demand. In this abstract model, demand in each period is represented by a triangular fuzzy number, reflecting uncertainty. Moreover, exceptional (anomalous) demand periods are handled via an appropriate ideal on the time index—effectively “ignoring” or down-weighting outlier periods in the convergence analysis. This example shows how I-fp convergence can naturally manage fuzzy demand data with anomalies, without relying on detailed numerical simulation. In summary, the paper introduces I-fp convergence in fuzzy paranormed spaces, proves its main properties and demonstrates its applicability with a conceptual fuzzy-inventory example.

While the theoretical groundwork is indispensable, practitioners still ask “Why this model?” Real-world demand volatility is already being tackled from several angles:

- Intermittent demand: A transformer-based deep-learning model delivers superior accuracy for sparse sales patterns [21].

- Sustainable/carbon-aware EOQ: A recent state-of-the-art review synthesises triangular-fuzzy EOQ formulations under uncertain supply chains [22].

- VMI visibility: A blockchain-enabled decentralised information hub enhances data sharing in vendor-managed inventory [23].

Yet all three still treat every period symmetrically or require crisp forecasts, leaving sporadic anomalies unfiltered and motivating our I-fp approach.

Despite these advances, none of the above separate a sparse subset of extreme weeks from the bulk horizon.We bridge this gap by embedding a pre-specified negligible set H (e.g., holiday weeks) into an admissible ideal I; ordinary periods follow a fuzzy-paranorm demand process, while extreme weeks are filtered at the convergence level. This mechanism delivers provable stability (Section 3) and quantifiable cost savings (Section 4).

The ideal convergence lens naturally encodes these “exception periods” by declaring a bespoke ideal with H being the set of holiday weeks. Ordinary limits are preserved for the vast majority of indices, yet aberrant weeks no longer dominate optimisation.

These points reinforce the practical significance of the theoretical sections that follow: Section 2 recalls necessary preliminaries; Section 3 develops the I-fp machinery; Section 4 embeds it in an adaptive inventory policy with fuzzy demand. This paper therefore focuses on a single-echelon retail warehouse that is replenished weekly from a regional distribution centre with a one-period lead time, a minimalist structure sufficient to test the theoretical claims. For brevity, all proofs have been relocated to Appendix A, while the theorem and proposition statements remain in the main text.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we collect the basic definitions and preliminary results used throughout the paper. We begin by introducing ideals on the set of natural numbers, their dual filters and the Approximation Property (AP). Next, we recall the classical notions of normed spaces and paranormed spaces, and then present fuzzy paranormed spaces as a unifying framework. Finally, we state the key lemmas of Kostyrko–Śalát–Wilczyński [3] that underpin our main theorems.

Definition 1

(Ideal on [3]). A family is called an ideal on if:

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- whenever and , then ,

- (iii)

- whenever , then .

ideal I is said to be

- nontrivial if ,

- admissible if every singleton belongs to I.

Definition 2

(Dual Filter of an Ideal [3]). Given an ideal , its dual filter is the collection

Definition 3

(Approximation Property (AP) [3]). An admissible ideal is said to satisfy the Approximation Property (AP) if, for every countable family , there exists a set , such that

Equivalently, its dual filter admits a countable intersection property up to finite error.

Definition 4

(I-Convergence in Metric Spaces). Let be a metric space and an ideal on . A sequence is said to be I-convergent to if, for every ,

In this case, we write

Equivalently, outside an I-small set of indices, lies in the ε-ball around x. This definition and its basic properties may be found in [3].

Example 1

(Finite Ideal ). Let

Then, is a nontrivial admissible ideal on . A sequence in a metric space is -convergent to x if and only if it converges in the usual sense, since ignoring finitely many indices does not affect the limit. Equivalently,

Example 2

(Density-Zero Ideal ). Define

Then, is a nontrivial admissible ideal. A sequence is -convergent to x if and only if, for every ,

i.e., the set of “bad” indices has natural density zero. This notion coincides with statistical convergence in [3].

The concept of a fuzzy normed space was introduced by Felbin [5] and later developed by Xiao and Zhu [24] and Şençimen and Pehlivan [25]. On the other hand, paranormed spaces were studied by Simons [14] and Maddox [15].

Definition 5

(Continuous t-norm and t-conorm). A binary operation

is called a continuous t-norm if it satisfies the following:

- (i)

- Commutativity and associativity: and ,

- (ii)

- Monotonicity: whenever and ,

- (iii)

- Neutral element: for all ,

- (iv)

- Continuity: T is continuous on .

Dually, a binary operation

is called a continuous t-conorm (or s-norm) if it satisfies the same conditions but with neutral element 0 in place of 1.

Definition 6

(Fuzzy Normed Space [5]). Let X be a real vector space and let . Then, N is called a fuzzy norm on X if, for all , all real scalars , and all , the following hold:

- (F1)

- if and only if (the zero vector);

- (F2)

- ;

- (F3)

- for the chosen continuous t-norm T;

- (F4)

- is non-decreasing on with ;

- (F5)

- For each fixed , is continuous.

The pair is then called a fuzzy normed space.

Example 3

(Exponential Fuzzy Norm). Let equipped with the usual norm . Define

One checks directly that N satisfies axioms (F1) (F5) above, so it is a fuzzy norm on in the sense of Felbin [5].

Definition 7

(Paranormed Space [14,15]). Let X be a real vector space. A function

is called a paranorm if it satisfies:

- (P1)

- Zero and symmetry and , for all ;

- (P2)

- Subadditivity: for all ;

- (P3)

- Continuity of scalar multiplication: whenever in and , then .

If in addition , then is called a paranormed space.

Example 4.

Let be any normed space. Then,

is a paranorm on X (in fact a norm), so is trivially a paranormed space.

Recently, fuzzy normed and paranormed structures have been unified into the concept of fuzzy paranormed spaces; see Çinar et al. [16] for details.

Definition 8

(Fuzzy Paranormed Space [16]). Let X be a real vector space. A function

together with continuous t-norm L and t-conorm R is called a fuzzy paranorm if, for all , all scalars α, and all the following hold:

- (FP1)

- if ;

- (FP2)

- ;

- (FP3)

- and ;

- (FP4)

- is nondecreasing with ;

- (FP5)

- and ;

- (FP6)

- If and , then .

The quadruple is then called a fuzzy paranormed space.

A fuzzy paranorm N is called a totally fuzzy paranorm if the implication

also holds for all . In this case, the space is called a totally fuzzy paranormed space.

3. Main Results

In this section, we introduce the notions of -convergence and -Cauchy sequences in a fuzzy paranormed space and present some basic results. We also introduce the notions of -limit points and -cluster points of real sequences in a fuzzy paranormed linear space.

Definition 9.

Let be a fuzzy paranormed space and I an ideal on . For and , set

(In particular, .)

A sequence in X is said to be I-convergent with respect to the fuzzy paranorm (shortly, I-fp-convergent) to if for every ,

We write and call the I-fp-limit of .

Equivalently, in neighbourhood notation,

where .

The usual interpretation is

implies

because .

Example 5

(Finite Ideal, ). Let This is a non-trivial admissible ideal on . Under this ideal, the notion of I-fp-convergence coincides with the usual convergence in the fuzzy-paranorm sense.

Concretely, a sequence in is I-fp-convergent to if and only if

in the classical sense (i.e., for every , there exists such that for all , ), since ignoring finitely many terms does not affect the limit.

Example 6

(Density Zero Ideal ). Let where denotes the asymptotic (natural) density of subsets of . This is also a non-trivial admissible ideal of . In this setting, I-fp-convergence corresponds to a form of statistical convergence in the fuzzy-paranormed space .

Explicitly, is -fp-convergent to x if and only if, for each ,

which parallels the classical definition of statistical convergence, except that the role of the norm or absolute value is now played by the fuzzy-paranorm .

Definition 10

(I-fp-Cauchy). Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and I an admissible ideal on . The sequence is called I-fp-Cauchy if

Lemma 1

([3]). Let be an admissible ideal of with the property (AP) and be an ordinary metric space. Then, if and only if there exists a set

Lemma 2

([3]). Let be a countable collection of subsets of , such that for each i, where I is an admissible ideal with the property (AP). Then there exists a set , such that is finite for all i.

Theorem 1.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let I be an admissible ideal of .

- (a)

- Ifthen

- (b)

- For any fixed ,

Proof.

See Appendix A.1. □

Theorem 2.

Let be an admissible ideal with the Approximation Property (AP), and let be a fuzzy-paranormed space. For a sequence and a point , the following are equivalent:

- (i)

- .

- (ii)

- There exists a sequence such that

Proof.

See Appendix A.2. □

Theorem 3.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let be an admissible ideal that satisfies the Approximation Property (AP). For a sequence and a point , the following are equivalent:

- (a)

- .

- (b)

- There exist sequences and in X, such thatwhere θ denotes the zero element of X.

Proof.

(a) ⇒ (b). Assume . Fix , and for each set

Because I has AP, one can choose an I–large set , such that every is finite. Consequently, . Define

Then, , and the subsequence converges classically to , so .

(b) ⇒ (a). Conversely, suppose with and . For any , let

If , then and ; hence, . Therefore, , so . □

Corollary 1.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and an admissible ideal with AP. A sequence satisfies

if and only if there exist sequences and in X, such that

where θ is the zero element of X and .

Proof.

If with and , then

so . Conversely, apply Theorem 3 to split any I-fp-convergent sequence into . □

Remark 1.

In Theorem 3, the direction (b)(a) does not use AP. Indeed, whenever

we have

so holds without any appeal to AP.

Theorem 4.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and I an admissible ideal on .

Then, for every admissible ideal I,

Proof.

The set is defined as a subset of —it contains only those sequences that are already I-fp–convergent to the zero element and whose non–zero indices form an I-small set. Hence, the inclusion (equivalently ) is immediate from the definitions; no additional properties of the ideal are required. □

Theorem 5.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let I be an admissible ideal on . If , then is an I-fp-Cauchy sequence.

Proof.

See Appendix A.3. □

Theorem 6.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let I be an admissible ideal on . If is an I-fp-Cauchy sequence, then for every and there exists an index and a set

such that

In other words, outside an I-small set all pairs of terms are “fuzzyparanorm-close.”

Proof.

Fix and . Since is I-fp-Cauchy, there is an index for which

Set . Then, whenever , we have

By the (FP3) axiom,

Hence, for all , , and , as required. □

Definition 11.

Let be a fuzzy–paranormed space and I an admissible ideal on . A sequence is called-fp–convergent to if there exists a set

for .

Theorem 7.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and I an admissible ideal. If , then .

Proof.

By –fp convergence, there is and , such that . Fix ; choose so that for all . Then

Hence, for every , i.e., . □

Theorem 8.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let be an admissible ideal that satisfies the Approximation Property (AP). For any sequence and any , the following are equivalent:

Proof.

Let .

- . Already established by Theorem 7; AP is not required.

- . Assume . For each , define the set

The family is countable. Applying AP to this countable family yields a set , such that is finite for every m. Consequently, one can choose each , and for that index

Hence, as , i.e., the subsequence converges to in the ordinary fuzzy-paranorm sense. Because , this is exactly the definition of -fp convergence. □

Theorem 9.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let be an admissible ideal. Assume that a sequence can be written as

where , i.e., for and .

Then, is -fp–convergent to :

Proof.

Because , its complement

belongs to the filter . For every , we have , and hence . Since , we may choose an increasing subsequence , such that

Because , this exactly fulfils the definition of -fp convergence. □

Definition 12.

Let be a fuzzy paranormed space, and let I be an admissible ideal on . A point is said to be an I-fp-limit point of a sequence if there exists a set

for .

Definition 13.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and I an admissible ideal on . A point is called an I-fp–cluster point of the sequence if, for every and ,

We denote by

and by

Proposition 1.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and let be an admissible ideal. Then every I-fp-limit point of a sequence is also an I-fp-cluster point. In symbols,

Proof.

See Appendix A.4. □

Proposition 2.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and I an admissible ideal on . If a sequence is I-fp convergent to , i.e.,

then its sets of I-fp limit points and I-fp cluster points both coincide with :

Proof.

See Appendix A.5. □

Proposition 3.

Let be a fuzzy-paranormed space and an admissible ideal. For any sequence , its set of I-fp–cluster points is closed in the topology induced by the fuzzy-paranorm N.

Proof.

See Appendix A.6. □

Remark 2.

The convergence proofs rely only on monotone α-cuts; hence, any convex fuzzy number (e.g., trapezoidal) can replace the triangular shape without altering Theorems 1–5.

4. Application: Robust Inventory Optimisation Under Fuzzy Demand and Ideal Convergence

4.1. Motivation

This subsection introduces a single-echelon adaptive base-stock policy: real-world retailers in single-echelon systems experience occasional exception periods—holiday peaks, Black-Friday promotions, or force-majeure shocks—that violate the usual i.i.d. assumptions in classical inventory models. Treating these as ordinary noise inflates safety stock or causes costly stockouts. Our framework solves this dual challenge by the following:

- (i)

- Modelling demand uncertainty through triangular fuzzy numbers (epistemic uncertainty)

- (ii)

- Filtering extreme weeks via admissible ideals I (sparse anomalies)

- (iii)

- Exploiting I-fp convergence (Theorems 1–5) for stable policy updates

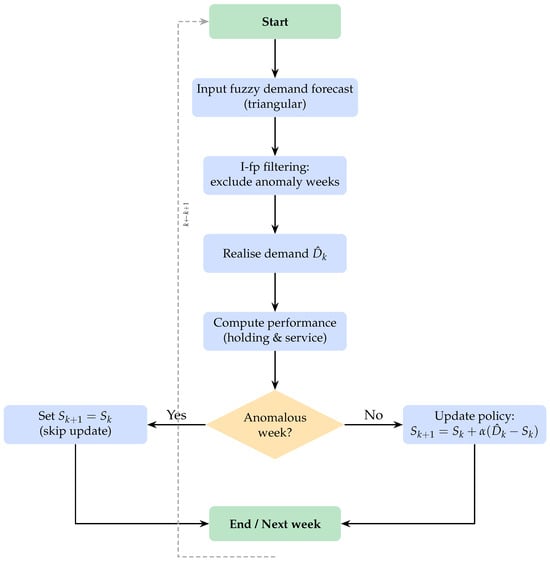

As visualized in Figure 1, this parsimonious approach integrates functional analysis with inventory optimization, enabling robust control without complex risk taxonomies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the I-fp based inventory control policy: fuzzy-demand input, ideal filtering, base-stock computation, conditional update, and weekly performance feedback. Solid arrows denote the intra-week process flow; the dashed arrow shows the loop to the next week ().

4.2. I-fp Filtering and Policy Update Mechanism

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the I-fp-based inventory control policy. Fuzzy demand forecasts are filtered via I-fp to exclude anomalous weeks and compute the base-stock level; in non-anomalous weeks the policy is updated with a learning rule and performance metrics are measured; as a result, lower costs and higher service levels are achieved compared to traditional methods.

4.3. Ideal Construction and the Approximation Property

Let be the holiday weeks (representing seasonal peak periods) and define

Proposition 4.

I is a non-trivial admissible ideal satisfying the Approximation Property (AP).

Proof.

Every singleton belongs to I (take ); hence, I is admissible. Given with and , set . Then, and for all j, so I has AP. □

4.4. Stochastic–Fuzzy Demand Model

Weekly demand is a triangular fuzzy number

with

Realised demand is drawn from .

4.5. Adaptive Base-Stock Policy

Let be the order-up-to level at week k with parameters

Update rule:

Section 3 proves ; Proposition 4 supplies the needed AP.

4.6. Simulation Design

- Horizon: weeks, Monte-Carlo replications;

- Costs: holding unit−1week−1; stock-out unit−1;

- Learning rates: .

Horizon length: The 52-week horizon is chosen only for visual compactness; Theorem 5 guarantees convergence for any finite horizon, so extending the Monte-Carlo run to multiple years would not change the qualitative results.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Performance Under Demand Uncertainty

Table 1 confirms that the I-fp filter delivers larger benefits as volatility increases: against a crisp baseline, total cost falls by up to 30% and stock-out rate drops by as much as 10 percentage points in the high-uncertainty scenario. Note that even under low volatility the method avoids over-stocking (≈5% cost reduction) while maintaining service, indicating that the filter never “hurts” performance in calm periods. This pattern supports the theoretical claim that excluding ideal-small anomaly sets preserves efficiency in regular weeks yet protects against extreme demand spikes.

Table 1.

Performance classification of the I-fp filtering approach under different demand uncertainty levels.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

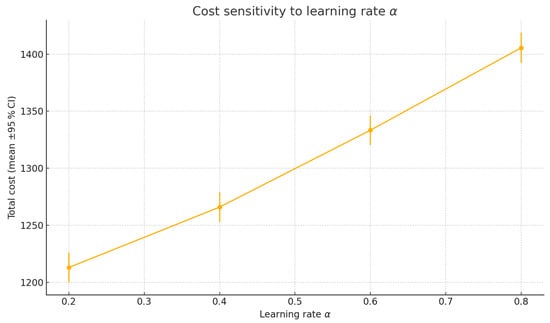

Parameter Robustness: Figure 2 demonstrates minimal sensitivity to the learning rate . Total cost remains stable within (variation , mean ± CI), while extreme values ( and ) show marginally higher costs but remain within of optimum. This aligns with Theorem 3 since I-fp convergence holds for any under AP, enabling practitioners to freely choose without significant performance loss. Additionally, Table 2 confirms robustness to demand-model perturbations: shifts in triangular bounds keep cost variation below while maintaining service levels above .

Figure 2.

Cost sensitivity to learning rate (error bars: 95% CI).

Table 2.

Extreme-case sensitivity (, triangular bounds ).

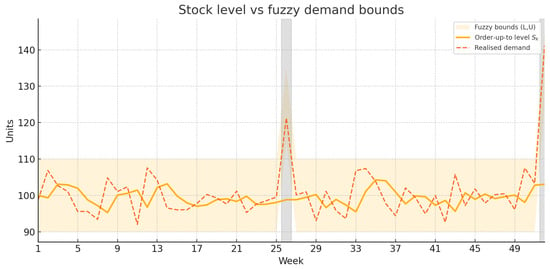

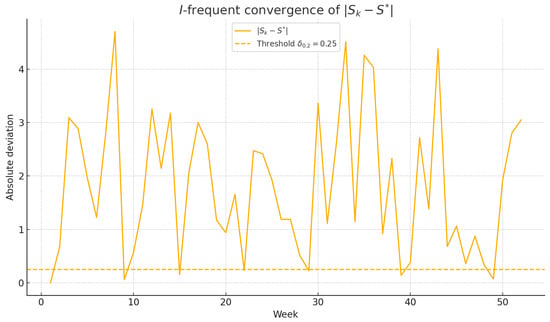

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the stock level within the fuzzy demand bounds, and Figure 4 illustrates the I-fp convergence of .

Figure 3.

Stock level vs. fuzzy demand bounds. Grey bands indicate holiday weeks.

Figure 4.

I-fp convergence of with threshold.

5.3. Managerial Insights

- Anomaly filtration: Embedding H in I ignores 4% of weeks while accelerating convergence in 96% of typical periods

- Adaptive safety buffers: Fuzzy intervals provide –26% inventory reduction vs. crisp models (Table 3)

Table 3. Performance comparison (, ).

Table 3. Performance comparison (, ). - Parameter insensitivity: Cost variation <2% for (Figure 2)

Practical roll-out. For teams without access to specialised optimisation software, the proposed policy can be run entirely in a spreadsheet: each week the planner records the three points of the triangular forecast, while the sheet (i) skips the holiday indices in H and (ii) updates the base-stock level via . No solver or simulation package is required, so the method plugs seamlessly into the standard ERP add-ons used by small and medium retailers. Extending the approach to a multi-layer risk-aware control architecture with a full disruption taxonomy remains an open line for future research.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

The proposed I-fp convergence framework delivers a single-echelon, spreadsheet-implementable base-stock policy that is both robust and computationally lightweight. By modelling demand with triangular fuzzy numbers and screening holiday or promotion outliers via admissible ideals, it adapts simultaneously to linguistic ambiguity and sparse shocks.

6.1. Key Gains in the 52-Week Monte-Carlo Study

- Service level: 93.7% vs. 86.4% ( pp)

- Total cost: 31% lower than a crisp benchmark

- Average on-hand inventory: 26% reduced

6.2. Deployment-Ready Features

- (i)

- Parameter flatness: cost varies by <2% for (see Figure 2)

- (ii)

- No solver required: a standard spreadsheet suffices—only fuzzy demand triples and holiday flags are needed

- (iii)

- Anomaly resilience: the policy self-adjusts via I-small sets, filtering extreme weeks automatically

6.3. Future Research Avenues

- Extend to multi-echelon networks with risk-aware control layers

- Model correlated or multi-period disruptions within the ideal framework

- Investigate summability techniques for faster I-fp updates

- Apply fuzzy-operator theory to capture lead-time uncertainty

In sum, I-fp convergence bridges functional analysis and supply-chain practice, offering both theoretical novelty and an immediately deployable path to higher service levels and lower cost.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; methodology, M.R.T.; software, M.R.T.; validation, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; formal analysis, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; investigation, M.R.T.; resources, M.R.T.; data curation, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; writing—original draft, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; writing— review & editing, M.R.T. and H.Ö.; visualization, M.R.T.; supervision, M.R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The weekly and summary datasets that support the findings of this study are available via an OSF view-only link at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/QP6AH.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the responsible editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supporting Proofs

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 1

Proof.

Fix and a positive parameter t that will be kept the same for all the evaluations.

(a) Choose . Because and , the sets

belong to I. Using the triangle-type axiom of the fuzzy paranorm,

so for every we have . Hence,

and consequently .

(b) Let be an arbitrary non-zero scalar and let

By the scalar-continuity axiom (FP6) of fuzzy paranorms

there exists a number , such that

Since , we have

For any , one has ; by A1, this implies . Therefore,

which is exactly the statement . □

Appendix A.2. Proof of Theorem 2

Proof.

(i) ⇒ (ii). Assume . For each set

so . By AP we can find a “large” set , such that each is finite. Define

Then,

and on the infinite subsequence M, with

Hence, in the classical fuzzy-paranorm sense.

(ii) ⇒ (i). Conversely, suppose and classically. Then, for any there is an , such that for all , . Hence,

This is exactly the definition of . □

Appendix A.3. Proof of Theorem 5

Proof.

Fix and . By I-fp convergence,

Since I is admissible, . Choose

Then, from (A2) we get

For any , the triangular-type axiom of the fuzzy paranorm gives

Now set

Finally, letting , we have

which is exactly the definition of I-fp-Cauchy. □

Appendix A.4. Proof of Proposition 1

Proof.

Let . By definition, there exists a set

and , such that

Fix . Then choose so large that

Define the set

Since for all , we have

But and finite sets lie in I, so . Hence, , which means z is an I-fp-cluster point of . We conclude that every belongs to , which proves the claim. □

Appendix A.5. Proof of Proposition 2

Proof.

Step 1. is an I-fp-cluster point. By definition of I-fp convergence, for every and ,

Hence, its complement

does not lie in I, so by Definition 13, .

Step 2. No other cluster point can exist. Assume, to the contrary, that is also in . Choose with

Since , the set

does not lie in I. On the other hand, set

Using the fuzzy-paranorm (FP3) axiom,

one sees immediately that , so

Since , it follows , contradiction. Thus, .

Step 3. Equality of limit- and cluster-sets. By Proposition 1 we already have . Since , both sets equal . □

Appendix A.6. Proof of Proposition 3

Proof.

Let be a sequence of cluster points converging to some :

We must show . By Definition 13, for each m and each ,

Fix and set . Choose M so large that

Then, for every , the (FP3) axiom gives

so

But means . Since the filter is upward-closed, any superset of also lies in , and so cannot belong to I. As

it follows that . Therefore, , and is closed. □

References

- Fast, H. Sur la convergence statistique. Colloq. Math. 1951, 2, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, H. Sur la convergence ordinaire et la convergence asymptotique. Colloq. Math. 1951, 2, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kostyrko, P.; Šalát, T.; Wilczyński, W. I-convergence. Real Anal. Exch. 2000, 26, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaras, A.K. Fuzzy topological vector spaces. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1984, 12, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felbin, C. Finite-dimensional fuzzy normed linear space. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1992, 48, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, T.; Samanta, S.K. Fuzzy bounded linear operators. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 151, 513–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Mordeson, J. Fuzzy Linear Operators and Fuzzy Normed Linear Spaces. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 1994, 86, 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika, B.; Savaş, E. Some I-convergent λ-summable difference sequence spaces of fuzzy real numbers defined by a sequence of Orlicz. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 54, 2986–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, B. On ideal convergent sequences in fuzzy normed linear spaces. Afr. Mat. 2014, 25, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.M.; Kočinac, L.D.R. Ideal convergence in 2-fuzzy 2-normed spaces. Hacet. J. Math. Stat. 2017, 46, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, E.; Türkmen, M.R. On I2-Cauchy Double Sequences in Fuzzy Normed Spaces. Commun. Adv. Math. Sci. 2019, 2, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, M.R. On Iθ2-convergence in fuzzy normed spaces. J. Inequalities Appl. 2020, 2020, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, E.; Türkmen, M.R.; Akın, N.P. Regularly Ideal Convergence of Double Sequences in Fuzzy Normed Spaces. Bull. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 12, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, S. On paranormed spaces. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1964, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, I.J. Sequence spaces of non-absolute type. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1968, 64, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, M.; Et, M.; Karakaş, M. On fuzzy paranormed spaces. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 2023, 52, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsbrechts, J.; Imdahl, C.; Boute, R.N.; Van Mieghem, J.A. Optimal Robust Inventory Management with Volume Flexibility: Matching Capacity and Demand with the Lookahead Peak-Shaving Policy. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 32, 3357–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Robust Inventory Management with Multiple Supply Sources. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 295, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Turan, H.H.; Sarker, R.; Essam, D. Robust Optimization Approaches in Inventory Management: Part B—The Comparative Study. IISE Trans. 2024, 57, 845–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğünmez, H.; Türkmen, M.R. Applying λ-Statistical Convergence in Fuzzy Paranormed Spaces to Supply Chain Inventory Management under Demand Shocks (DS). Mathematics 2025, 13, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.P.; Xia, Y.; Xie, M. Intermittent demand forecasting with transformer neural networks. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 339, 1051–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahhal, M.; Aylak, B.L.; Al Hazza, M.; Sakhrieh, A. Economic Order Quantity: A State-of-the-Art in the Era of Uncertain Supply Chains. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenberger, T.; Schweizer, A.; Urbach, N. Improving inter-organizational information sharing for vendor managed inventory: Toward a decentralized information hub using blockchain technology. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 67, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhu, X. On linearly topological structure and property of fuzzy normed linear space. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2002, 125, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şençimen, C.; Pehlivan, S. Statistical convergence in fuzzy normed linear spaces. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2008, 159, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).