Abstract

We establish a theory whose structure is based on a fixed variable and an algebraic inequality and which improves the well-known least squares theory. The mentioned fixed variable plays a basic role in creating such a theory. In this direction, some new concepts, such as p-covariances with respect to a fixed variable, p-correlation coefficients with respect to a fixed variable, and p-uncorrelatedness with respect to a fixed variable, are defined in order to establish least p-variance approximations. We then obtain a specific system, called the p-covariances linear system, and apply the p-uncorrelatedness condition on its elements to find a general representation for p-uncorrelated variables. Afterwards, we apply the concept of p-uncorrelatedness for continuous functions, particularly for polynomial sequences, and we find some new sequences, such as a generic two-parameter hypergeometric polynomial of the type that satisfies a p-uncorrelatedness property. In the sequel, we obtain an upper bound for 1-covariances, an improvement to the approximate solutions of over-determined systems and an improvement to the Bessel inequality and Parseval identity. Finally, we generalize the concept of least p-variance approximations based on several fixed orthogonal variables.

Keywords:

Least p-Variance approximations; least squares theory; p-Covariances and p-Correlation coefficients; p-Uncorrelatedness with respect to a fixed variable; Hypergeometric polynomials; generalized Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization process MSC:

93E24; 62J10; 42C05; 33C47; 65F25

1. Introduction

Least squares theory is known in the literature as an essential tool for optimal approximations and regression analysis, and it has found extensive applications in mathematics, statistics, physics and engineering [1,2,3,4]. Some important parts of this theory include the following: the best linear unbiased estimator, Gauss–Markov theorem, the moving least squares method and its improvements [5,6,7], least-squares spectral analysis, orthogonal projections and least squares function and polynomial approximations [8]. See also [9] for synergy interval partial least squares algorithms. It was officially discovered and published by A. M. Legendre [10] in 1805, though it is also co-credited to C. F. Gauss, who contributed significant theoretical advances to the method and may have previously used it in his work in 1795 [11]. The base of this theory is to minimize the sum of the squares of the residuals, which are the difference between observed values and the fitted values provided via an approximate linear (or nonlinear) model. In many linear models [12], in order to reduce the influence of errors in the derived observations, one would like to use a greater number of samplings than the number of unknown parameters in the model, which leads to so-called overdetermined linear systems. In other words, let be a given vector and for a given matrix. The problem is to find a vector, , such that is the best approximation to b. There are many possible ways of defining the best solution; see [13]. A very common choice is to let x be a solution of the minimization problem , where denotes the Euclidean vector norm. Now, if one refers to as the residual vector, a least squares solution in fact minimizes . In linear statistical models, one assumes that the vector of observations is related to the unknown parameter vector through a linear relation

where is a predetermined matrix of rank n, and e denotes a vector of random errors. In the standard linear model, the following conditions are known as the basic conditions of Gauss–Markov theorem:

i.e., the random errors, , are uncorrelated and all have zero means with the same variance, in which is the true error variance. In summary, the Gauss–Markov theorem expresses that, if the linear model (1) is available, where e is a random vector with mean and variance given by (2), then the optimal solution of (1) is the least squares estimator, obtained by minimizing the sum of squares . Furthermore, , where . Similar to other approximate techniques, the least squares method contains some constrains and limitations, just like in the above-mentioned theorem, such that the conditions (2) are necessary. In this research, we introduce a new fixed variable in the minimization problem to somehow miniaturize the primitive quantity associated with sampling errors. For this purpose, we begin with a basic identity which gives rise to an important algebraic inequality, too. Let denote an inner product space. Knowing that the elements of satisfy four properties of linearity, symmetry, homogeneity and positivity, there is an identity in this space that is directly related to the definition of the projection of two arbitrary elements of , i.e.,

where indicates the inner product of and and denotes the norm square value of . In other words, suppose that are three specific elements of , and is a free parameter. Noting (3), the following identity holds true:

and, naturally, for , it leads to the Schwarz inequality

This identity can also be considered in mathematical statistics. Essentially, as the content of this research is about the least variance of an approximation based on a fixed variable, if we equivalently use the expected value symbol instead of the inner product symbol , though there is no difference between them for use, we will get to a new definition of covariance concept, as follows:

Definition 1.

p-Covariances with respect to a fixed variable.

Let and Z be three random variables and . With reference to (4), we correspondingly define

and call it “p-covariance of X and Y with respect to the fixed variable Z”.

Note, in (6), that

and, therefore, e.g., for ,

If and Z follows a constant distribution, say , where , then (6) will reduce to an ordinary covariance as follows:

Also, for , it follows that the fixed variable Z has no effect on Definition (6).

For in (6), an extended definition of the ordinary variance is concluded as

where is always to be positive.

Moreover, for any fixed variable Z and , we have

which is equivalent to

in an inner product space. Note that, after simplification, the second part of the latter inequality is in the same form as (5). Although inequality (8) shows that the best option is , we prefer to apply the parametric case throughout this paper. The reasons for making such a decision will be revealed in forthcoming sections (see the illustrative Section 2.4 in this regard). The following properties hold true for Definitions (6) and (7):

(a1)

(a2)

(a3)

(a4)

(a5)

(a6)

- and

Definition 2.

p-Correlation coefficient with respect to a fixed variable.

It is straightforward to observe that , because, if the values

are replaced in the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality [14]

then . In this sense, note that

which are equal to zero only for the case .

Definition 3.

p-Normal standard variable with respect to a fixed variable.

Definition 4.

p-Uncorrelatedness with respect to a fixed variable.

If, in (10), which is equivalent to the condition

then we say that X and Y are p-uncorrelated with respect to the fixed variable Z.

Such a definition can be expressed in an inner product space, too. We say that two elements, , are p-uncorrelated with respect to the fixed element if

or, equivalently,

As (12) shows, gives rise to the well-known orthogonality property. In summary, 0-uncorrelatedness gives the orthogonality notion, results in complete uncorrelatedness and leads to incomplete uncorrelatedness. We will use the phrase “complete uncorrelated” instead of 1-uncorrelated.

The aforesaid definition can similarly be expressed in a probability space. We say that two events, A and B, are p-independent with respect to the event C if

which is equivalent to

Hence, e.g., 1-independent means a complete independent with respect to the event C.

2. Least p-Variances Approximation Based on a Fixed Variable

Let and Y be arbitrary random variables, and consider the following approximation in the sequel

in which are unknown coefficients to be appropriately determined.

According to (7), the p-variance of the remaining term

is defined with respect to the fixed variable Z as follows:

where shows the projection of the error term (14) on the fixed variable Z and the projection of each elements on Z. For the special case , we have in fact considered (15) as

We wish to find the unknown coefficients in (15), such that is minimized. In this direction, it is important to point out that, according to inequality (8), the following inequalities always hold for any arbitrary variable Z:

This means that inequalities (16) are valid for any free selection of , especially when they minimize the quantity (15). In other words, we have

which shows the superiority of the present theory with respect to the ordinary least squares theory (see Section 2.4 and Section 3 in this regard).

To minimize (15), for every we have

leading to the linear system

Notice that only finding the analytical solution of the above system is sufficient to guarantee that is minimized, because we automatically have

For instance, after solving (2.6) for , the approximation (13) takes the form

In general, two continuous and discrete cases can be considered for the system (18), which we call from now on a “p-covariances linear system with respect to the fixed variable Z”.

2.1. Continuous Case of p-Covariances Linear System

If , and are defined in a continuous space with a probability density function as , for any arbitrary function positive on the interval , then the components of the linear system (18) appear as

where .

2.2. Discrete Case of p-Covariances Linear System

If the above-mentioned variables are defined on a counter set, say with a discrete probability density function as , for any arbitrary function positive on , then

where .

One of the important cases of the approximation (13) is when has a constant distribution function, which leads to the Hilbert problem [13,15] in a continuous space and to the polynomial type regression in a discrete space. In other words, if , , and for are substituted into (18), then

and

For , we clearly encounter with the Hilbert problem.

Similarly, if in a discrete space , , where , and , the entries of the system (18), respectively, take the forms

and

As a particular sample, the system corresponding to the linear regression with respect to the fixed variable appears as

It is interesting to know that, if is substituted into the above partially system for , the output gives the well-known result

i.e., has been automatically deleted. In this sense, if the only case is substituted into the above mentioned system for as

the output gives the result , where is a free parameter.

In the next section, we show why became a free parameter when and .

2.3. Some Reducible Cases of the p-Covariances Linear System

2.3.1. First Case

Suppose there exists a specific distribution for the fixed variable Z, such that

Then, the p-covariances system (18) reduces to the well-known normal equations system

and

Also, it is obvious for that

2.3.2. Second Case

If Z follows a constant distribution (say ) and , the condition (21) is no longer valid for because . Therefore, noting the fact that , the linear system (18) reduces to

Relation (24) shows that for , is a free parameter. For , the approximation (13) takes the simplified form , and replacing it in the normal system (22) yields

Now, the important point is that, after some elementary operations, the system (25) will exactly be transformed into the linear system (24). This means that, for any arbitrary , we have

Such a result in (26) can similarly be proved for every where , as the following example proves.

2.4. An Illustrative Example and the Role of the Fixed Variable in It

The previous Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3 affirm that the fixed variable Z plays a basic role in the theory of least p-variances. Here, we present an illustrative example to show the importance of such a fixed function in constituting the initial approximation (13). Let be defined on together with the probability density function and the fixed function , where because . For the basis functions , the initial approximation (13) takes the form

in which the unknown coefficients satisfy the following linear system according to (18):

where

After solving (28), will be determined, and since the remaining term of (27) is defined as

so

However, there are two different cases for the parameter , which should be studied separately.

2.4.1. First Case

If , then the fixed functions coincide, respectively, with the first, second, and third basis functions in (27), and the system (28) is simplified for as

and for as

and finally for as

According to the result (26), the solutions of all above systems must be the same and independent of p so that, in the final form, we have

Note for , after solving (28), we get

in which according to (26) again.

In this sense, , implies that

2.4.2. Second Case

Any assumption other than causes the system (28) to have a unique solution. For example, simplifies (28) in the form

After solving the system (29), we obtain

For the special case , i.e.,

we have

and consequently

As we observe

which clearly shows the role of the fixed function in the obtained approximations.

2.5. How to Choose a Suitable Option for the Fixed Variable: A Geometric Interpretation

Although inequality (28) holds for any arbitrary variable Z, our wish is to determine some conditions to find a suitable option for the fixed variable Z, such that

and/or

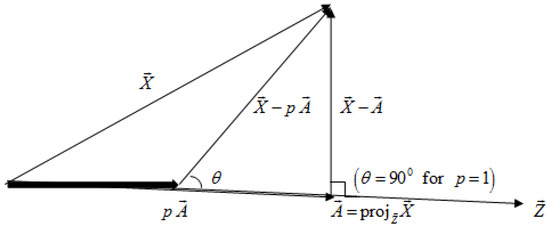

Various states can be considered for the above-mentioned goal. For example, replacing in (31) yields which means that, if the magnitude of the mean value is very big, we expect that the presented theory based on the fixed variable acts much better than the ordinary least squares theory. Another approach is to directly minimize the value in (30), such that . The Figure 1 describes our aim in a vector space.

Figure 1.

Least p-variances based on the fixed vector and the role of p from 0 to 1.

In this figure, leads to the same as ordinary least squares for , leads to the complete type of least variances based on and , and finally, leads to the least p-variances based on and .

8. On the Ordinary Case of p-Covariances

When and , we have . Replacing these assumptions in (43) as

generates an ordinary uncorrelated element. Note that the leading coefficient in (43) has no effect on being uncorrelated, and we have therefore ignored it in the above determinant.

There are, in total, two cases for the initial value in (185), i.e., when is a constant value (preferably ) or it is not constant. As we have shown in Section 2.3.2, the first case leads to the approved result (26), whereas the non-constant case contains some novel results. The next subsection describes one of them.

10. A Unified Approach for the Polynomials Obtained in Section 7, Section 8 and Section 9

According to the distributions given in Table 1, only beta and gamma weight functions can be considered for the non-symmetric infinite cases of uncorrelated polynomials, as the normal distribution is somehow connected to a special case of gamma distribution. In this direction, the general properties of two polynomials, (177) and (187), reveal that the most general case of complete uncorrelated polynomials relevant to the beta weight function is when and , i.e., where and . Hence, if the corresponding uncorrelated polynomial is indicated as , we have

provided that

The components of the determinant (172) corresponding to this generic polynomial are computed as follows

in which and .

According to the preceding information, the polynomials (177) can be represented as

and the polynomials (187) as

and noting (213), since

the shifted polynomials (210) on are represented as

Similarly, the most general case of complete uncorrelated polynomials relevant to the gamma weight function is when and , i.e., where and . Therefore, if the corresponding uncorrelated polynomial is indicated as , then

provided that

The components of the determinant (172) corresponding to this second generic polynomial are computed as

in which .

As a sample, the polynomials (218) can be represented as

12. An Upper Bound for 1-Covariances

As the optimized case is , in this part, we are going to obtain an upper bound for . Let and be real numbers, such that

It can be verified that the following identity holds true:

Noting the conditions (244) and this fact that

equality (245) leads to the inequality

On the other hand, following (246) in the well-known inequality

gives

One of the direct consequences of (247) is that

where the constant in (248) is the best possible number in the sense that it cannot be replaced with a smaller quantity. As a particular case, if, in (248), we take

it will reduce to the weighted Grüss inequality [29,30]

in which

13. An Improvement to the Approximate Solutions of Over-Determined Systems

For , consider the linear system of equations

whose matrix representation is as where

As we mentioned in the introduction, the linear system (249) is called an over-determined system since the number of equations is more than the number of unknowns.

Such systems usually have no exact solution, and the goal is instead to find an approximate solution for the unknowns that fit equations in the sense of solving the problem

It has been proven [13] that the minimization problem (250) has a unique vector solution, provided that the m columns of the matrix A are linearly independent, which is given by solving the normal equations where indicates the matrix transpose of A, and is the approximate solution of the least squares type expressed by

Instead of considering the problem (250), we would like now to consider the minimization problem

based on the fixed vector , where the quantity (251) is clearly smaller than the quantity (250) for any arbitrary selection of . In this direction,

leads to the linear system

which can also be represented as the matrix form

with the solution

A simple case of the approximate solution (253) is when and , i.e., an ordinary least variance problem such that (253) becomes

Example 3.

Suppose , and . Then, the corresponding over-determined system takes the simple form

and the problem (251) reduces to

Hence, the explicit solutions of the system (252), i.e.,

are, respectively,

and

while the approximate solutions corresponding to the well-known problem (250) are

and

Let us compare these two series of solutions for a particular numerical case. If, for instance,

then the solutions of the ordinary least squares problem are while the solutions corresponding to the minimization problem (254) are

By substituting such values into the remaining term

we observe that

whereas

On the other hand, for the well-known remaining term

we observe that

whereas

In conclusion,

which confirms inequality (16).

14. An Improvement of the Bessel Inequality and Parseval Identity

In general, two cases can be considered for this purpose.

14.1. First Type of Improvement

Let be a sequence of continuous functions which are p-uncorrelated with respect to the fixed function and the probability density function on as before. Then, according to (44),

denotes a p-uncorrelated expansion for in which

Referring to Corollary 2 and relation (59), the following inequality holds true for the expansion (255):

Also, according to the definition of convergence in p-variance, inequality (256) will be transformed to an equality if

which results in

If (257) or, equivalently, (258) is satisfied, the p-uncorrelated sequence is said to be “complete” with respect to the fixed function , and the symbol “∼” in (255) will change to the equality. Noting the above comments, now let be two expandable functions of type (255), and let be a “complete” p-uncorrelated sequence. Since

and

thanks to the general identity

and the fact that we obtain

which is an extension of the identity (258) for . Also, for , this important identity leads to the generalized Parseval identity [16]

The finite type of (259) occurs when and are all polynomial functions. For example, let denote the same as polynomials (224) satisfying

Also let be two arbitrary polynomials of the same degree. Since

and

according to (259), we have

14.2. Second Type of Improvement

As inequality (57) is valid for any arbitrary selection of the coefficients , i.e.,

such kind of inequalities can be applied for orthogonal expansions. Suppose that is a sequence of continuous functions orthogonal with respect to the weight function on . If is a piecewise continuous function, then

is known as its corresponding orthogonal expansion in which . The positive quantity

will eventually lead to the Bessel inequality [15]

Now, noting (261) and (262), instead of , we define the following positive quantity:

It is clear that

Therefore,

can be rewritten as

Inequality (264) is an improvement of the well-known Bessel inequality for every with respect to the fixed function . For example, if for and are replaced in (264), the Bessel inequality of the Fourier sine expansion will be improved as follows

Obviously (264) will remain an inequality if the sequence does not form a complete orthogonal system. On the other side, if they are a complete orthogonal set, inequality (264) becomes an equality when . In other words, suppose is a complete orthogonal set. Since

we directly conclude from (263) that

and, therefore,

eventually yields

which is known in the literature as the inner product form of the generalized Parseval identity (260). In the next section, we will refer to the above-mentioned results in order to extend the presented theory in terms of a set of fixed mutually orthogonal variables.

15. Least p-Variances with Respect to Fixed Orthogonal Variables

Since parts of this section are somewhat similar to the previous ones, we just state basic concepts. Suppose and are elements of an inner product space , such that are mutually orthogonal as

Due to the orthogonality property (265), the following identity holds true

and, for , it gives

The identity (266) and inequality (267) can again be employed in mathematical statistics concepts.

Definition 6.

Let and be arbitrary random variables, such that are mutually orthogonal, i.e.,

Corresponding to (266), we define

and call it the “p-covariance of X and Y with respect to the fixed orthogonal variables ”.

For , (269) changes to

where are all positive. Note in (269) that

and, therefore, e.g., for ,

Moreover, for orthogonal variables and , we have

A remarkable point in (271) is that, if are two natural numbers, such that , then

which can be proved directly via (270). For instance, if and , then

in which

The following properties hold true for definitions (269) and (270), provided that the orthogonal condition (268) is satisfied:

Definition 7.

Definition 8.

15.1. Least p-Variances Approximation Based on Fixed Orthogonal Variables

Again, consider the approximation (13), and define the p-variance of the remaining term with respect to the orthogonal variables as follows:

To minimize (273), the relations

eventually lead to the following linear system:

Two continuous and discrete spaces can be considered for the system (274).

15.1.1. First Case

If , and the orthogonal set are defined in a continuous space with a probability density function as the elements of the system (274) appear as

if only if

15.1.2. Second Case

If the above-mentioned variables are defined on a counter set, say , with a discrete probability density function as then

only if

Let us consider a particular example. Suppose that , and . In this case, it is well known that, if we take and , then

and, therefore,

The weighted version of the above example can be considered in various cases. For example, if and all defined on , then

and consequently the corresponding space is defined as

where

In the sequel, applying the uncorrelatedness condition

on the elements of the linear system (274), we can obtain the unknown coefficients as

In this case,

is the best approximation in the sense of least p-variance of the error with respect to the fixed orthogonal variables .

Finally, we point out that p-uncorrelated vectors with respect to fixed orthogonal vectors can be constructed as follows. Let and be two arbitrary vectors, and let be a set of fixed orthogonal vectors. Then,

if only if .

Funding

This work was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation under the following grant number: Ref 3.4-IRN-1128637-GF-E.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to three anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no competing interest.

References

- Van De Geer, S. A new approach to least-squares estimation, with applications. Ann. Stat. 1987, 15, 587–602. [Google Scholar]

- Kariya, T.; Kurata, H. Generalized Least Squares; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Casella, G. The bayesian lasso. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolberg, J. Data Analysis Using the Method of Least Squares: Extracting the Most Information from Experiments; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, P.; Salkauskas, K. Surfaces generated by moving least squares methods. Math. Comput. 1981, 37, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, D. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data. In Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference, New York, NY, USA, 27–29 August 1968; pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, B. Analysis of Meshfree Galerkin Methods Based on Moving Least Squares and Local Maximum-Entropy Approximation Schemes. Mathematics 2024, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Narayan, A.; Zhou, T. Constructing least-squares polynomial approximations. SIAM Rev. 2020, 62, 483–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, M.; Yan, C.; Zhang, T.; Tang, H.; Li, H. Quantitative analysis of biodiesel adulterants using raman spectroscopy combined with synergy interval partial least squares (siPLS) algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, A.M. Nouvelles Méthodes la Determination des Orbites des Comètes: Part 1–2: Mit Einem Supplement; Didot: Paris, France, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, S.M. Gauss and the invention of least squares. Ann. Stat. 1981, 9, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.R. Linear Models and Generalizations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Björck, Å. Numerical Methods for Least Squares Problems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. A functional generalization of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality and some subclasses. Appl. Math. Lett. 2009, 22, 1335–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.J.D. Approximation Theory and Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P.J. Interpolation and Approximation; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brezinski, C. Biorthogonality and Its Applications to Numerical Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iserles, A.; Nørsett, S. On the theory of biorthogonal polynomials. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1988, 306, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. A basic class of symmetric orthogonal polynomials using the extended Sturm–Liouville theorem for symmetric functions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 325, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. Special Functions and Generalized Sturm-Liouville Problems; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Area, I. Hypergeometric multivariate orthogonal polynomials. In Proceedings of the Orthogonal Polynomials: 2nd AIMS-Volkswagen Stiftung Workshop, Douala, Cameroon, 5–12 October 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 165–193. [Google Scholar]

- Milovanović, G.V. Some orthogonal polynomials on the finite interval and Gaussian quadrature rules for fractional Riemann-Liouville integrals. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2021, 44, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, G.V. On the Markov extremal problem in the L2-norm with the classical weight functions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.01094. [Google Scholar]

- Milovanovic, G.V. Orthogonality on the semicircle: Old and new results. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 2023, 59, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihara, T.S. An Introduction to Orthogonal Polynomials; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koepf, W. Hypergeometric Identities. In Hypergeometric Summation: An Algorithmic Approach to Summation and Special Function Identities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Koepf, W. Power series in computer algebra. J. Symb. Comput. 1992, 13, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. Biorthogonal Exponential Sequences with Weight Function exp (ax2+ ibx) on the Real Line and an Orthogonal Sequence of Trigonometric Functions. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 136, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. A linear constructive approximation for integrable functions and a parametric quadrature model based on a generalization of Ostrowski-Gruss type inequalities. Electron. Trans. Numer. Anal. 2011, 38, 218–232. [Google Scholar]

- Masjed-Jamei, M. A certain class of weighted approximations for integrable functions and applications. Numer. Funct. Anal. Optim. 2013, 34, 1224–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).