Abstract

This study presents an image inpainting model based on an energy functional that incorporates the norm of the fractional Laplacian operator as a regularization term and the norm as a fidelity term. Using the properties of the fractional Laplacian operator, the norm is employed with an adjustable parameter p to enhance the operator’s ability to restore fine details in various types of images. The replacement of the conventional norm with the norm enables better preservation of global structures in denoising and restoration tasks. This paper introduces a diffusion partial differential equation by adding an intermediate term and provides a theoretical proof of the existence and uniqueness of its solution in Sobolev spaces. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the solution converges to the minimizer of the energy functional as time approaches infinity. Numerical experiments that compare the proposed method with traditional and deep learning models validate its effectiveness in image inpainting tasks.

MSC:

68U10; 94A08

1. Introduction

Image inpainting is a vital task in image processing, with applications ranging from restoring old paintings and removing unwanted scratches or text from images to recovering lost data during transmission. Mathematically, images are considered as functions defined on a continuum, though in practice, digital images are discrete representations of their continuous counterparts. Formally, a digital image can be represented as a matrix . Due to various interferences in the image acquisition and transmission processes, the observed image data, , is often expressed as

where is a degenerate operator and is a random noise, typically assumed to be white Gaussian noise in this context. Thus, image inpainting becomes an inverse problem where the goal is to estimate from . The problem is ill-posed, making its solution nontrivial and requiring specialized methods for effective restoration.

A variety of techniques have been proposed to solve the image inpainting problem. Among the most widely used are diffusion-based methods, which leverage the information from neighboring regions to propagate data into damaged areas. These methods typically use partial differential equation (PDE)-based and variational-based frameworks for image restoration. Bertalmio et al. [1] introduced the first PDE-based inpainting model, which was simple but prone to producing blurred results due to the smoothness of differential operators. Subsequent work [2,3] sought to refine this approach by improving the handling of image features, but the issue of blur remained.

Variational methods, based on minimizing an appropriately designed energy functional, have become another cornerstone of image inpainting. A typical variational formulation is given by

where is a regularization parameter, and is a regularization term that controls the smoothness of the solution. Total variation (TV) models, introduced by Chan and Shen [4], are particularly popular due to their ability to preserve edges while filling in missing regions. However, TV methods often struggle with large missing areas or disconnected regions, leading to the staircase effect [5]. To address these issues, higher-order models such as those by Lysaker et al. [6] and adaptive PDE methods have been developed, offering improved smoothness and edge preservation [7,8].

In recent years, fractional-order PDEs have gained attention for image processing, offering better control over the smoothness and sharpness of restored images. Fractional differential operators replace standard differential operators with their fractional counterparts, leading to models that mitigate the oversmoothing effect commonly observed in traditional PDE-based methods [9,10]. These fractional models have shown promising results in both theoretical studies and practical applications [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Another notable approach to image inpainting is exemplar-based methods, which grow image regions pixel by pixel or patch by patch while maintaining coherence with the surrounding texture. These methods, popularized by Criminisi et al. [29], are especially effective in images with repetitive textures but struggle in the absence of suitable matching samples. Recent work has improved these methods by introducing nonlocal techniques [30,31] and hierarchical schemes [32], though structural connectivity remains a challenge.

In more recent years, deep learning-based inpainting techniques have achieved impressive results by leveraging generative models, such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [33,34] and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [35,36], to learn both high- and low-frequency features of the image. These models generate plausible content for missing regions by learning the underlying structure and texture of the image. Several architectures have been proposed to address different types of inpainting challenges, such as irregular hole filling [37], high-resolution restoration [38], and multiple-solution generation [39].

In the context of image inpainting, the use of the fractional Laplacian has gained significant interest in recent years. The fractional Laplacian, a nonlocal operator, provides a more accurate representation of spatial interactions compared to traditional local differential operators. The operator is defined as

where is any real number between 0 and 1, and denotes the principal value of the integral. Recent work [40,41] has focused on numerical methods for discretizing the fractional Laplacian, demonstrating its ability to improve image quality while avoiding the oversmoothing problem common to traditional methods.

Our original model [23] was based on the fractional Laplacian operator with the norm serving as the regularization term and the norm as the fidelity term. However, the paper lacked a theoretical proof of the solution to the diffusion equation. This article primarily explores the application of the fractional Laplacian operator in image inpainting tasks, and the inpainting results are quite promising. This paper represents an optimization of the original model which uses the norm of fractional Laplacian operator as the regularization term and the norm as the fidelity term and completes the theoretical framework. The inpainting results not only surpass those of the original model but also outperform some other models that were previously incomparable.

In summary, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Proposal of a novel image inpainting model: We introduce an image inpainting model based on an energy functional that combines the norm of the fractional Laplacian operator as a regularization term and the norm as a fidelity term.

- Theoretical derivation of the PDE system: We rigorously derive the Euler–Lagrange equations and the corresponding nonlinear partial differential equation (PDE) system within the variational framework. We prove the existence and uniqueness of weak solutions to this PDE system and show that, as time tends to infinity, the weak solution converges to the minimizer of the original energy functional.

- Stable numerical method: We design a stable numerical method for solving the PDE system, provide a discrete scheme for the fractional Laplacian operator, and conduct a theoretical analysis of the method’s stability and convergence.

2. Proposed Model

First of all, we explain some notation used in this paper. We use notation stands for Fourier transform defined as

where i stands for the imaginary unit, and . We use to indicate Schwartz space. For , the fractional Laplacian operator is defined as

The generalized fractional Laplacian operator is defined on distribution space , which is dual space of , as

Using the above notation, we define the Bessel potential space.

Definition 1 (Bessel potential space).

Let ; the Bessel potential space is defined as

The norm of Bessel potential space is defined as

This space has some special properties that we need to use in the subsequent proof. We can see the proof in proposition 3.10 and proposition 3.15 in [42].

Theorem 1.

For every , the space is complete and separable.

Theorem 2 (Fractional Sobolev embedding theorem).

Let , then

- If , then:and the embedding is continuous.

- If , thenand the embedding is continuous.

- If , thenand the embedding is continuous.

- Let , thenand the embedding is continuous.

- Let such that , thenwiththe embedding is continuous.

When processing an image u defined on a finite domain, we need to extend it to the entire space while preserving required regularity conditions. Let be a finite Lipschitz domain. The extension of u to , denoted by , must satisfy the following requirements:

Without the loss of generality, we use u to represent the extension function , and the subsequent function extensions in the paper will be constructed following this approach, such that the fractional Laplacian operator for the function u defined on the region can be expressed as

where is the extension of u.

We expand the definition of Bessel potential space in domain .

Definition 2.

The Bessel potential space defined on the open set is defined as

The norm is defined as

Theorem 3.

Let be a Lipschitz domain, then there exists a bounded linear extension operator:

such that .

By Theorem 3, Theorem 2 is established for Lipschitz domains.

Theorem 4

(Equal norm in ). The norm

is equivalent to in .

2.1. Inpainting Model

Suppose that is Lipschitz domain and is a closed set representing the inpainting area, , , and . Let

then our inpainting model is

Our model consists of two terms. The first one is the p-power of norm of , and the second term represents the square of norm for , where the distribution space is the dual space of . The first time using norm in image inpainting is in [43], in which it is said that not only but also this norm can better separate oscillatory components from high-frequency components compared to the norm, while also being better at removing noise while preserving edges.

Remark 1.

The operator represents the weak inverse of Δ. Given an open set is defined as follows: is the unique week solution of PDE (7) in space :

In other words, , where φ is a weak solution of Equation (7) that satisfies the following:

By taking in place of φ, we obtain the following:

We will use this operator to show why the norm can be written as . Let , and by Riesz’s theorem, there exists a unique such that

We expand the definition of as and take it in place of φ in the above equation, yielding

Thus, we use the definition of norm to obtain the following:

while we let , yielding the following:

By leveraging the advantage of it, we can confirm a simple fact: for all , we have and .

2.2. Euler–Lagrange Equation

Our derivation of the Euler–Lagrange (E-L) equations is a formal derivation.

Taking partial derivatives of (10) with respect to , we have

by the variational principle that brings into (12). We also obtain

By utilizing fractional Green’s identity (see Lemma 3.3 in [44]), we obtain the following:

where is fractional Neumann boundary operator defined as

Taking partial derivatives of (11) with respect to and letting , using Equation (8), we take in place of and in place of f and derive

then

from which we obtain the Euler–Lagrange equation as follows:

since we need this equality only for ; moreover, this integral does not exist when .

Introduce the intermediate variable where is defined from to . Applying Equation (8), we take in place of f and in place of and obtain

and (20) can be further written as

The Euler–Lagrange Equation (20) is a variational gradient for the minimum problem (6). Using that, we can construct diffusion equations to approach the minimum through time evolution; it is also known as gradient flow. Gradient flow is a dynamic process that describes how a function or system evolves over time to minimize a certain energy functional. Its core idea is to evolve along the negative gradient direction of the energy functional, gradually approaching the minimum.

2.3. Model Analysis

In this section, we will prove that diffusion Equation (23) yields a unique weak solution. The main reason for Equation (23) yielding a unique weak solution is that it consists of monotone operators. Our proof follows the book [45] about monotone operators in nonlinear partial differential equations while also drawing upon established theoretical frameworks in fractional PDE analysis [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. First, we define the monotone operators.

Define the operator as follows:

and the corresponding weak form is defined as

Let . It is easy to see that is continuous when and increases since . Moreover, it can be regarded as an operator from to and . Hence, can be seen as a linear functional regarding the second variable on which means .

has the following properties:

- Non-negative.

- Bounded. i.e., , ,

- Continuous for each variable.Let , , and in ; is a bounded linear operator from to , so in . Using the fact that when , the following holds:where is a constant independent of . So, we haveThe same proof can show that operator satisfies that the real-valued function for all , which is continuous.For the second variable,as .

- Monotonous, i.e., ,Sinceand the function is increased; if , then . Similarly, when , then ; therefore, we know .

The integral equations of system (23) is given by

and we should define the weak solution of integral system (28).

Definition 3.

Theorem 5.

For any , is a Lipschitz domain, and D is a closed subset of Ω; then, for any initial value , given , Equation (23) has a unique weak solution . Moreover, , and there exists a constant that is independent of α and p, such that

and

Proof.

We use Galerkin discretization to prove its existence. Let

then, through the Sobolev embedding theorem, we know that

and both embeddings are dense. Moreover, let be the inner product of , and be the solution operator of problem finding to given such that

is a self-adjoint, compact, non-negative, and , so through Hilbert–Schmidt’s theorem, there exists an orthonormal basis of consisting of eigenfunctions of T, and

where are the corresponding eigenvalues with as , then is an orthonormal basis of , which is the Galerkin basis that we need. Define , then

Due to the dense embedding, we have

Using the same arguments, there exists an orthonormal basis of , let , then

We use the following function:

to approximate the solution, where coefficient is the following ordinary differential equations:

where converge to in as . In order to simplify this, let

In ordinary differential Equation (30), let , and the function

can be proven that it is continuous in because of . Moreover, in region , it satisfies the local Lipschitz condition, and such that when is large enough, where stands for the Euclidean norm in . Hence, for any , there exists a unique solution that can be extended to ; for any given T, we consider the solution in finite region .

Since the equations are linear for and , we take in place of in (29), through which we get

the first equation in (31) multiplies and adds up with the second equation in (31), which we have as

since and using Grönwall inequality, we know , which only depends on T and , such that

Using the similar method, taking as test function in (29) leads to

Hence, using the estimates (32), (33), and (34), we know that such that

and

since is bounded, we have ; then, there exists functions , and such that there exists which is a sub-sequence of that satisfies as ,

it should be noted that by embedding theorem, some weak convergence can be strengthened, i.e.,

Moreover, using inequality (33), we know that when ,

hence, there exist a sub-sequence of without losing the generality still noted as , and it satisfies

then for any , we have

take u in place of ; then,

while integrating t in for (31),

By letting and applying the weak lower-semi-continuity of the norm together with (35), we have

then using the fact that and , and with the monotonous of , we have

for any and , set and let , after which we get

then use the same method by setting , through which we have

Next, we prove are the weak derivative of , for all , then with the definition of weak derivative, we obtain the following:

and then take and the completeness of , which satisfies that for all :

which show that are the weak derivatives of . Now, consider when ; for all , we have

and on the other hand, since and is bounded, ; therefore,

taking , through the completeness of , we have in . Using the same method, we can prove that and in .

Lastly, we prove the uniqueness of the solution: suppose and are two solution of systems (28), let , then

we have ,

in the equation above, let ; adding two equations, we have

using the monotonicity of , then

The proof is complete. □

The proof above demonstrates that for every , the diffusion Equation (23) yields a unique weak solution in . Moreover, due to the uniqueness of the solution, we can extend it to . We now investigate the behavior of the solution as . First, however, we establish the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Proof.

Theorem 6.

Proof.

For any , the weak solution satisfies integral Equation (28); we take in place of and in place of , then

using the fact that

and

we can get the first estimation as follows:

Considering , we have

multiply , and integrating , then

and we can get the second estimation as follows:

Meanwhile, consider the following equation

using the first equation of (37) and

we have

in estimation (40), we have , i.e.,

then we have the last estimation:

using inequalities (40) and (41), we know that

so we know there exist a sub-sequence such that and as , and from Lemma 1, we know

we have

which means , and we have

Equation (43) shows that as ,

and it has shown that the weak solution u weakly * converge to the solution of Euler–Lagrange Equation (20). Using estimation (40)–(42), there exists that depend on , and D such that

By Theorem 4, then there exists functions , and a sub-sequence such that when ,

and strongly in , strongly in . Moreover,

hence, there exists a sub-sequence of without losing the generality, still noted as , and it satisfies

using the same method in proving Theorem 5, we have

Proof.

The proof of inequality (45):

the second inequality:

we use Young’s inequality to prove the following:

□

3. Numerical Formats

3.1. Difference Scheme

Let and represent the time and space steps, respectively, then ; . Let be a matrix value of u and be a matrix value of , and the initial , . To approximate , we use forward difference, given by

Similarly, for , we have

Since the spatial discretization step size for images is fixed as , the boundary conditions of the Euler-Lagrange Equation (20) pose challenges in finite difference numerical implementations. For image-related problems, we assume the boundary conditions satisfy favorable properties, thus avoiding direct treatment of boundary issues. In the Euler–Lagrange (E-L) equations, the integral term outside is relatively complex. For this reason, our algorithm focuses only on the principal part of the equations. The difference formula of (23) will be half discretion for time given by

3.2. Discretization of Fractional Laplacian

The fractional Laplace operator in integral form definition as

where

In order to obtain the fractional Laplace operator for discrete image u, we give a discrete fractional Laplace operator. Let be an image since and we simplify . We can express the fractional Laplacian value of as

and assume that the side length of a square window is . In such a window, the fractional Laplacian value of can be expressed as

We get error analysis of the above numerical format. Assuming is the error of image u, let denote the numerical difference in and , given by

Thus, the absolute error is

where

and

the relative error will be

It is hard to compute the exact value of ; therefore, we use to approach it, and the difference of every step is

and then

The operator on the right-hand side of the first equation in (48) can be represented by the notation T defined in (24), we analogously use a window with length n to approach it, i.e.,

where , and the relative error will be

then the relative error of is

using the fact that when , the absolute error is

and then

Since an image are integers ranging from 0 to 255 while storing in a computer, we assume the way to change a function u into integers ranging from 0 to 255 will be

then we say that two function are the same when

We assume output image is not a constant, i.e., and has no error, i.e., , we want to compute the smallest n such that in the meaning of (52); in order to do so, we need

similarly, we want to compute the smallest n such that in the meaning of (52), and we need

In (48), we need to compute . Although we could use the expression with , this approach proves to be overly complicated. Here, we use

3.3. Algorithms

The following Algorithms 1–3 describe the workflow of our image inpainting model.

| Algorithm 1 Compute |

|

Based on Algorithm 1, we have two algorithms (Algorithms 2 and 3) for image inpainting in which we let D be an inpainting area where if is inpainting area, else .

| Algorithm 2 Inpainting for noise-free image |

|

| Algorithm 3 Inpainting and denoising |

|

In the above algorithms, we will employ the notation ⨀, which denotes the element-wise multiplication of matrices, i.e.,

4. Experimental Setup and Results

This section presents the experimental results including the effect of parameters and p in Algorithm 2 and relative analysis to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed image inpainting models. We compared our approach with several existing models, including traditional mathematical models and some deep learning models.

Our method is based on single-valued functions, so it is very suitable for grayscale image processing. When processing RGB images, we will process each RGB channel separately and then use the processed image as a result of image restoration. Our method is designed to fill light intensity to the missing area, and it requires the local smoothness of intensity value. When processing an HLS or HSB image, hue and saturation may not have such smoothness, so it is necessary to convert the HLS or HSB image to the RGB color space, apply our algorithm, and then transform the RGB image back to the HLS or HSB color space.

The metrics used to evaluate the quality of inpainted images will be peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure (SSIM). Given an image u and its noisy or inpainted approximation , PSNR and SSIM are defined as

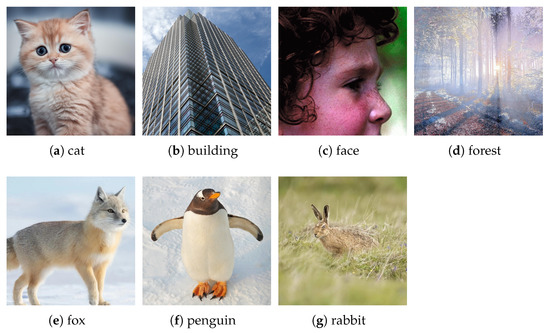

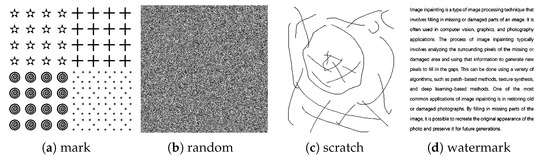

where is the maximum intensity value of image u; , , and represent expectation, covariance, and variance of images, respectively. Usually, the higher the values, the better the approximation of to u, which shows better inpainting performance. The images we used in the experiments are shown in Figure 1. The masks to be added to the images are shown in Figure 2, incorporating the mark, random loss 50%, scratch, and watermark.

Figure 1.

Ground-truth images.

Figure 2.

Mask images.

All experimental programs are coded in MATLAB R2023b and Python 3.11.8 under Windows 11 64-bit and run on a system equipped with a 3.70 GHz Intel Core i5-12600KF CPU and 32 GB of memory with GPU NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 12G and CUDA Version: 12.7.

4.1. Parameter Effect on Algorithms

The main computational part of our algorithm is Algorithm 1, in which the parameters and p affect the algorithm results and the computing speed. To show which parameters and p value will attain the best result, we take parameter for every step in an open interval and parameter p in every step in a closed interval to experiment, using the image cat Figure 1a and mask Figure 2a to show the effect.

Using inequality (53), we show how n will change with an increase in the parameter and the time to calculate 100 times using Algorithm 1. The results showed in Table 1 tell that window size will increase when and decrease when , and the computation time increases as n increases since the main computation in Algorithm 1 is convolved with an matrix.

Table 1.

Window size n and calculation time with a change in .

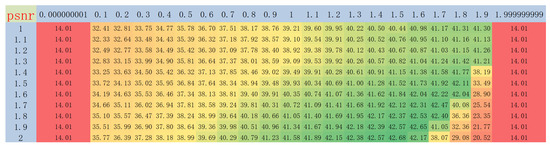

Both and p will affect the result in inpainting. To show what value of and p will get the best result, we used image cat Figure 1a and mask mark Figure 2a and used Algorithm 2 for inpainting, using PSNR (56) to show the performance of the combination of these two parameters. The results are shown in Figure 3, where the rows represent the value of p and the columns represent the value of . We can see that the best result happened when and .

Figure 3.

PSNR result with the change in and p. PSNR values are color-coded from red (lowest: 14.01 dB) to green (highest: 42.68 dB), with intermediate values transitioning through yellow.

Furthermore, after conducting many experiments on various images and masks, the results have shown that the highest PSNR values are achieved when and . Meanwhile, while using our algorithm in image inpainting, we recommend choosing a small value for when the mask is a thicker line.

4.2. Inpainting

This section presents the experimental results and relative analysis to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed image inpainting models. We compared our approach with several existing models, including traditional mathematical models, Total Variation (TV) [66], Total Generalized Variation (TGV) [67], Frequency Total Variation (ftTV) [68], and Adaptive modified Mumford–Shah Inpainting (AMSI) [69], and some deep learning models, Globally and Locally Consistent Image Completion (GLCIC) [70], Rethinking Image Inpainting via a Mutual Encoder–Decoder with Feature Equalizations (MEDFE) [71], and Aggregated Contextual Transformations for High-Resolution Image Inpainting (AOT-GAN) [72].

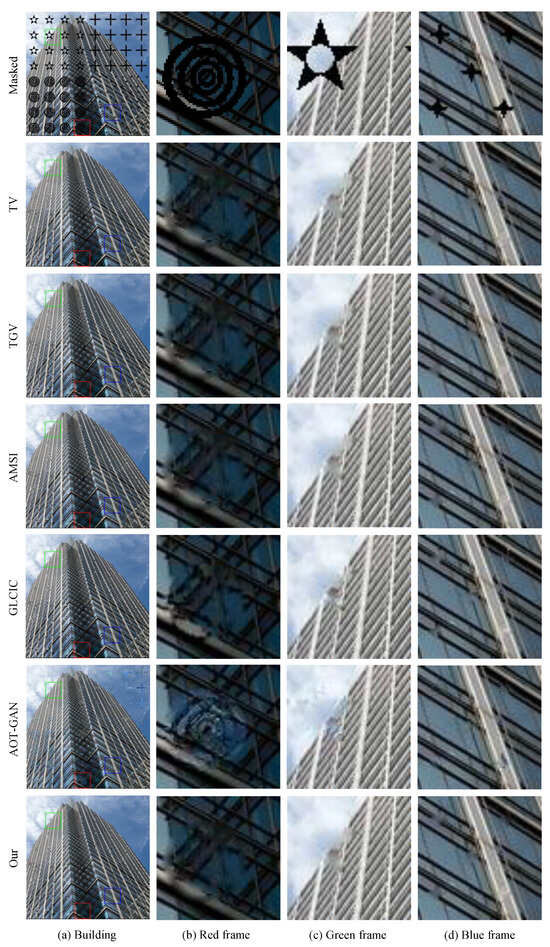

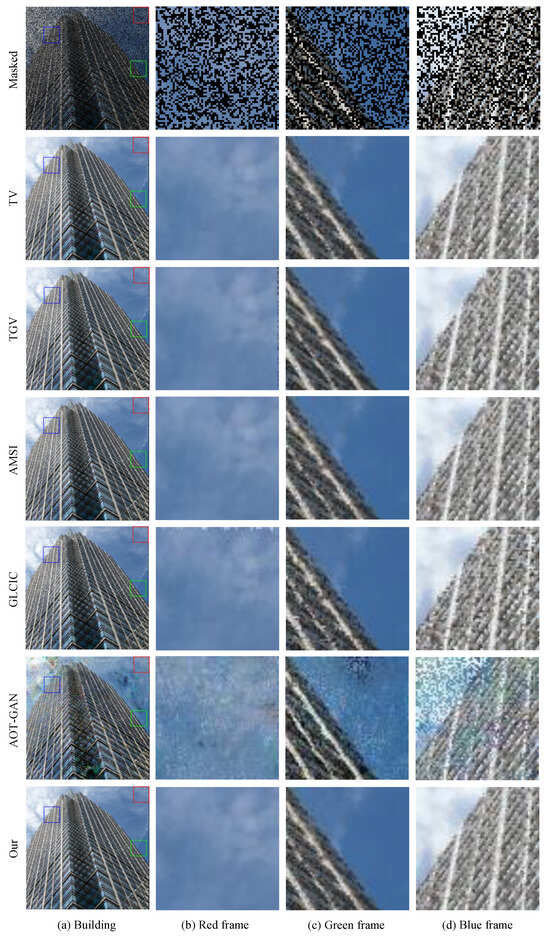

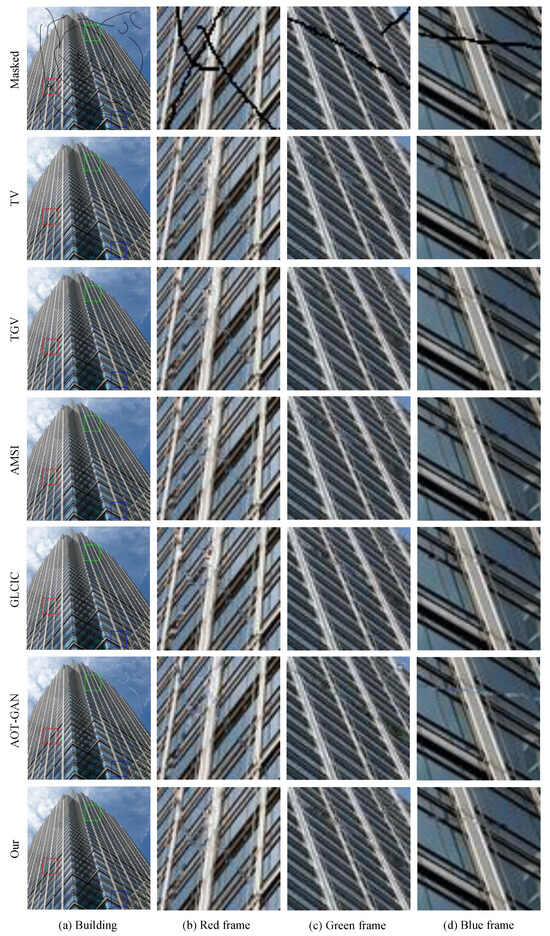

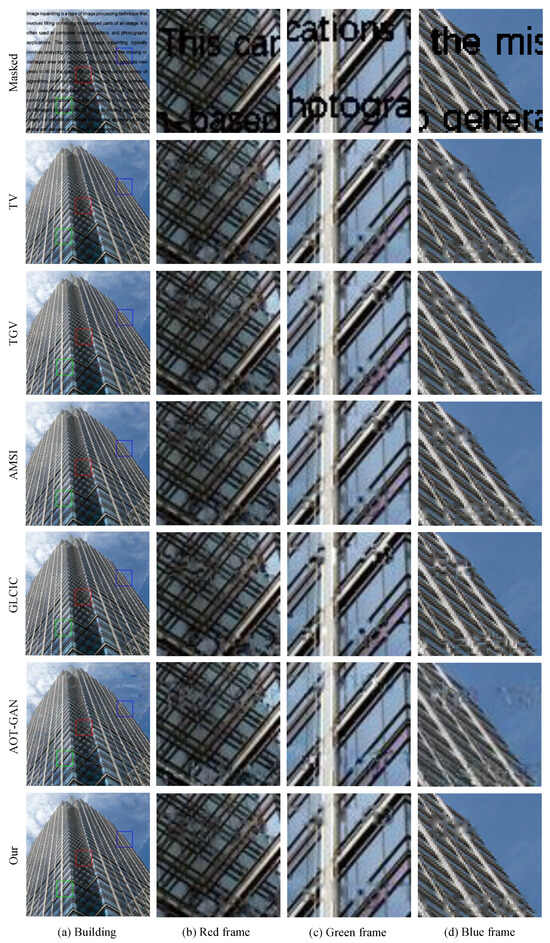

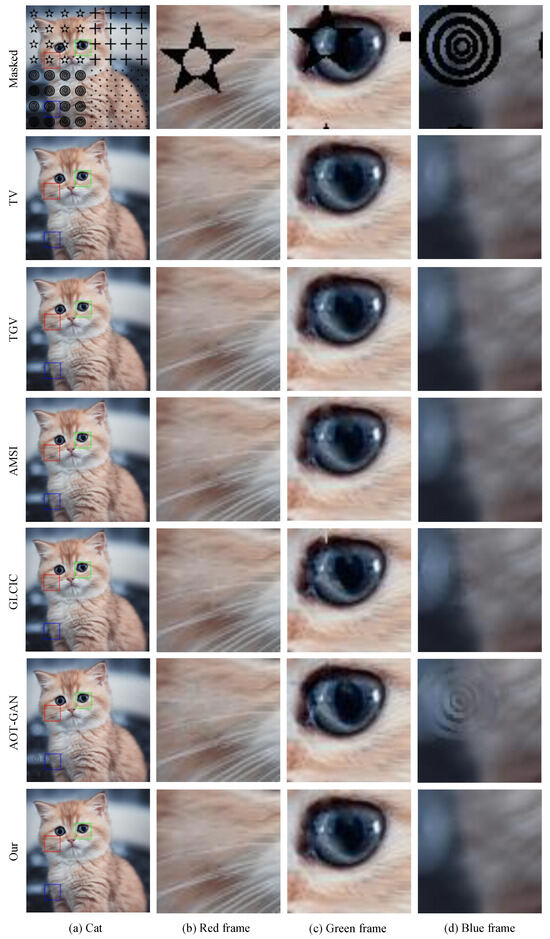

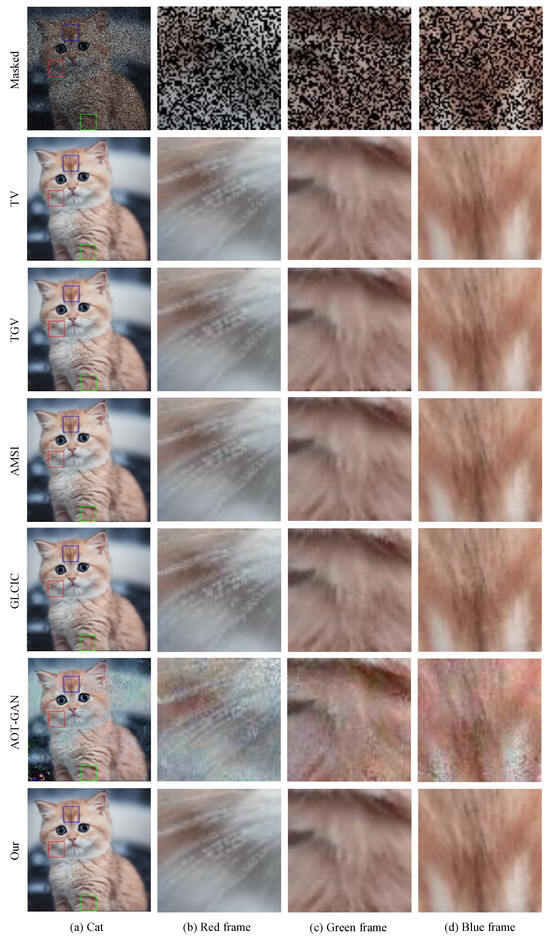

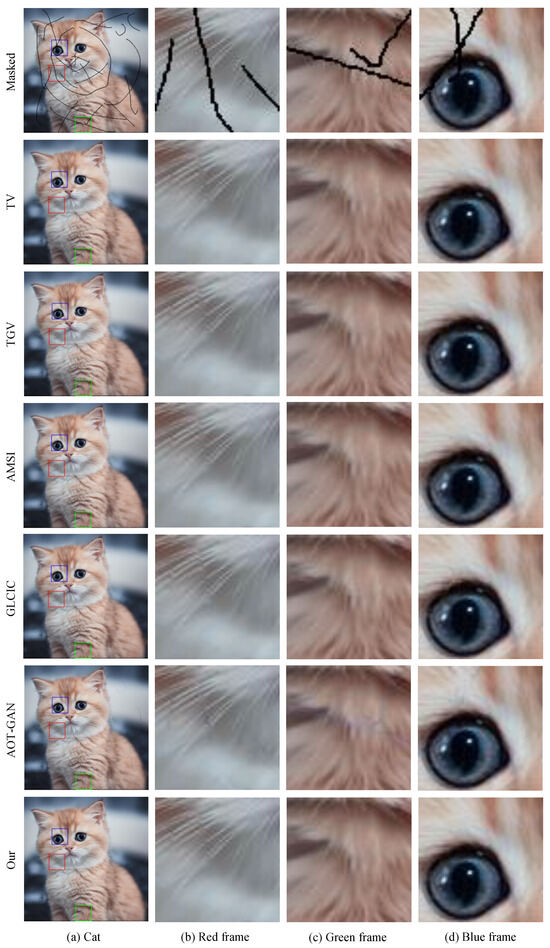

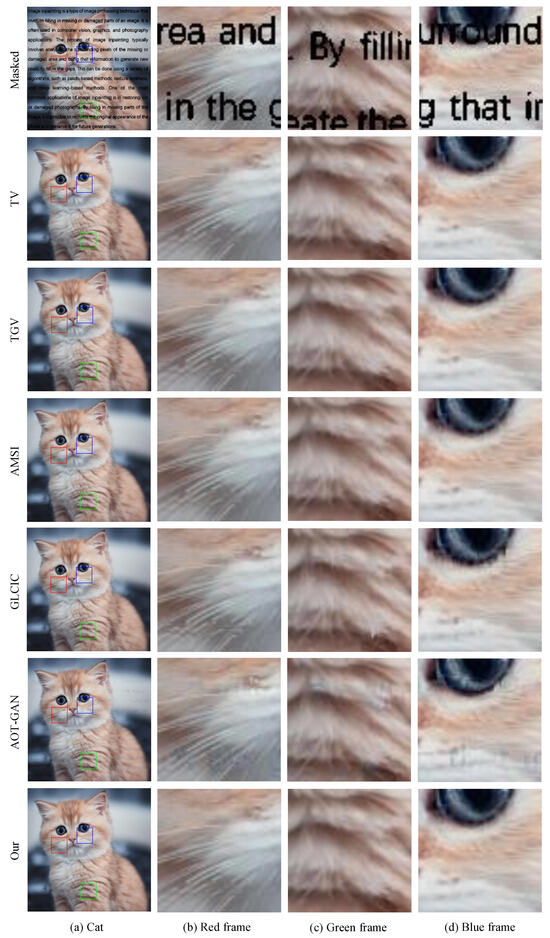

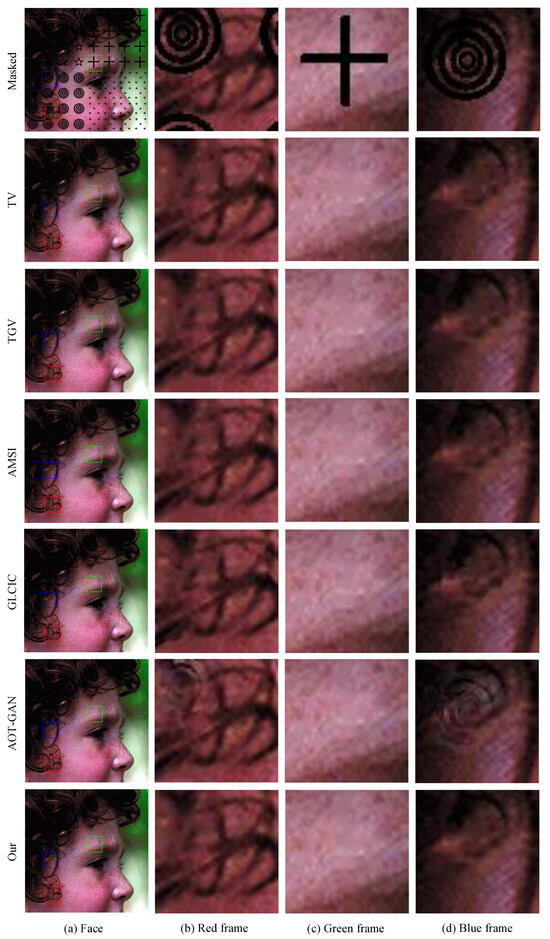

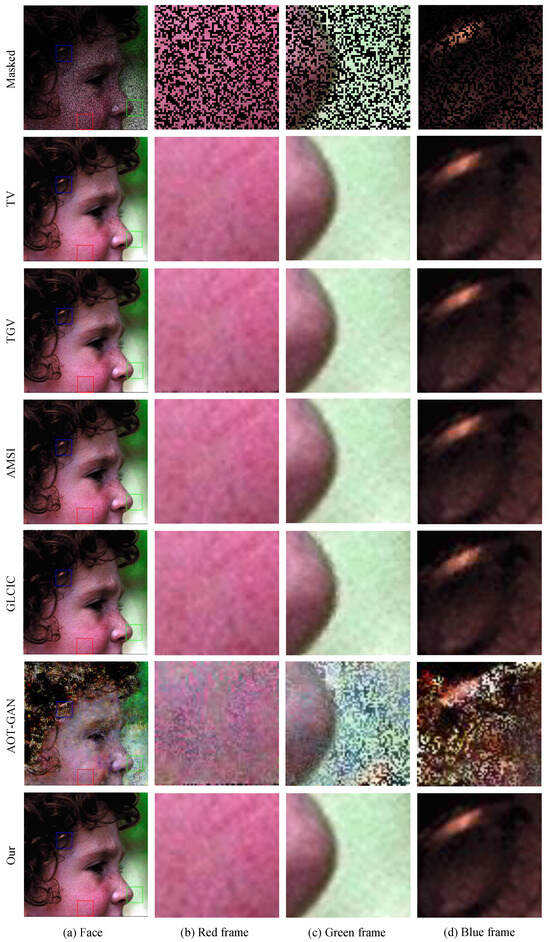

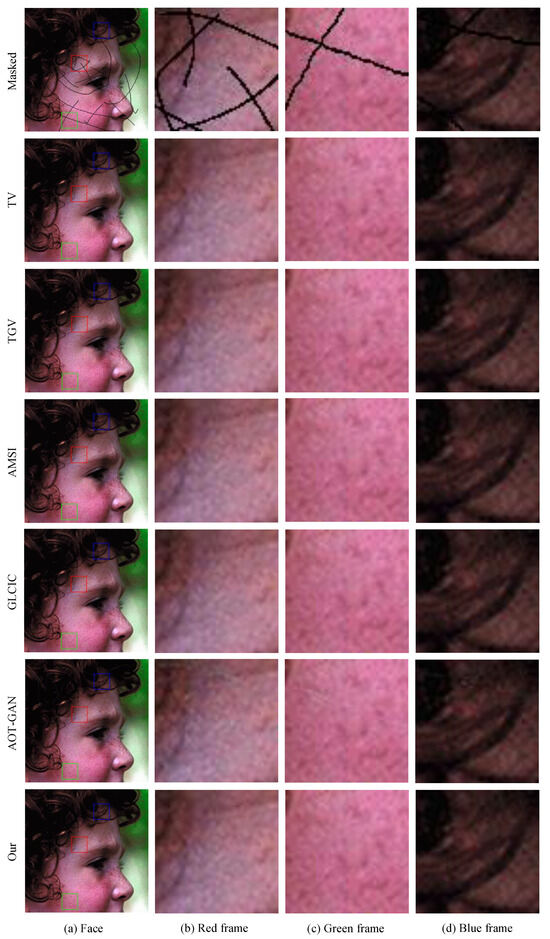

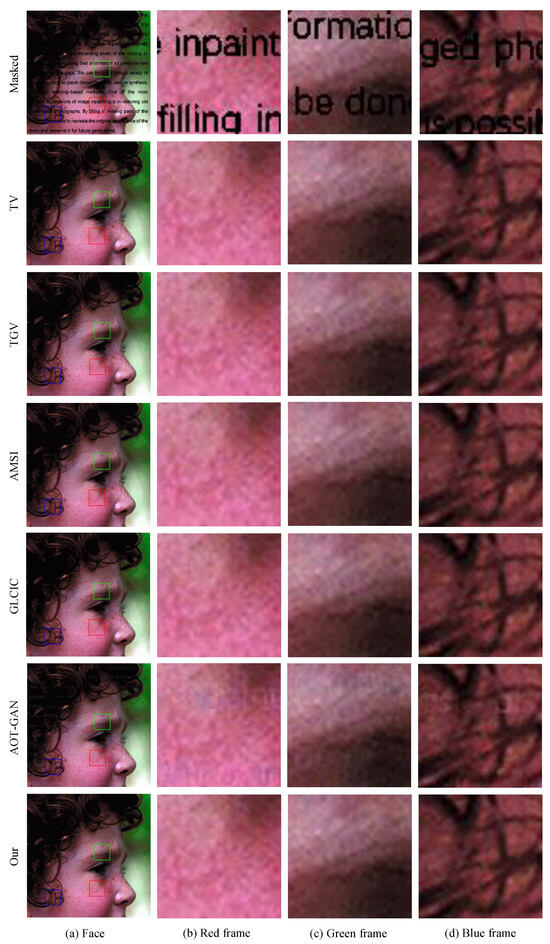

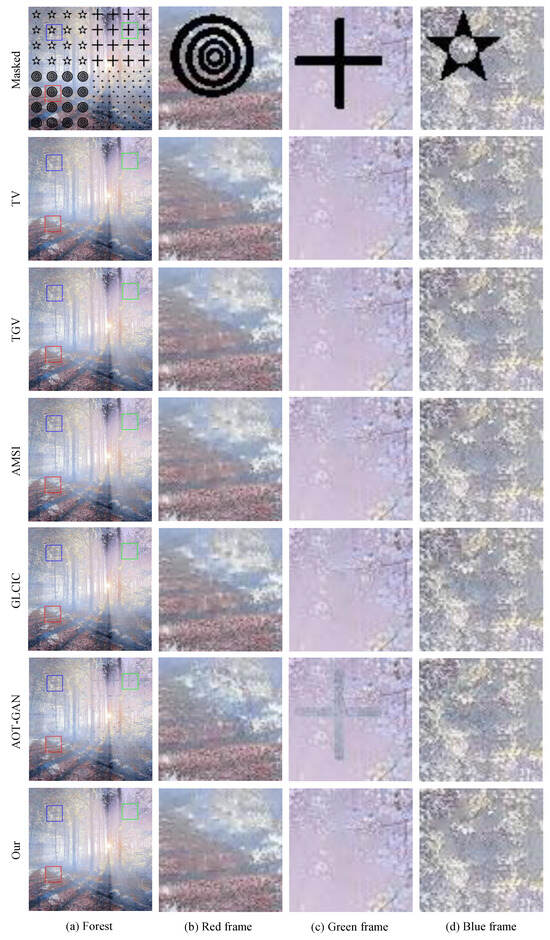

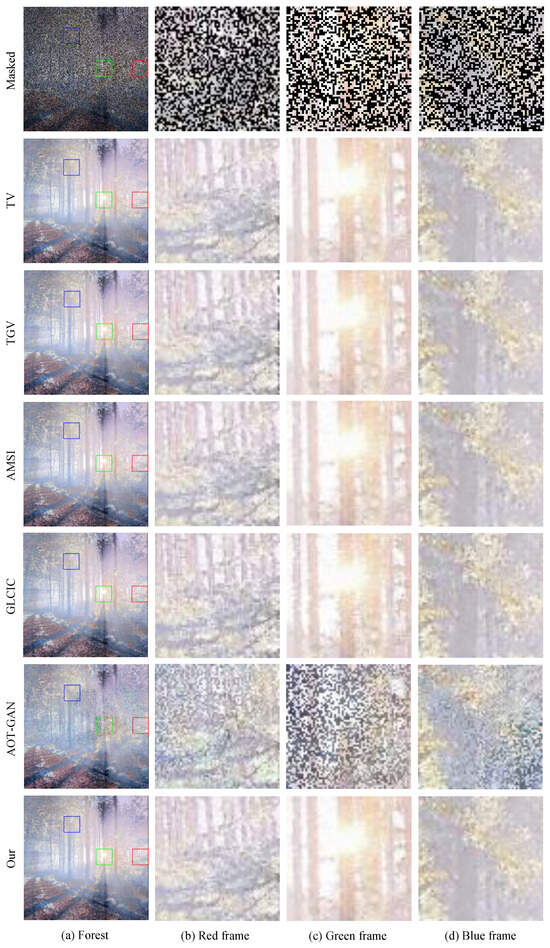

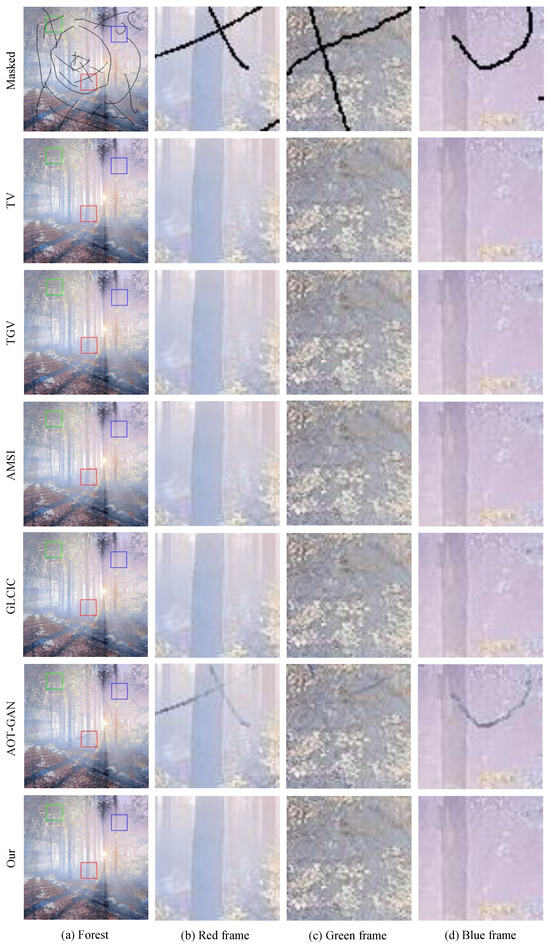

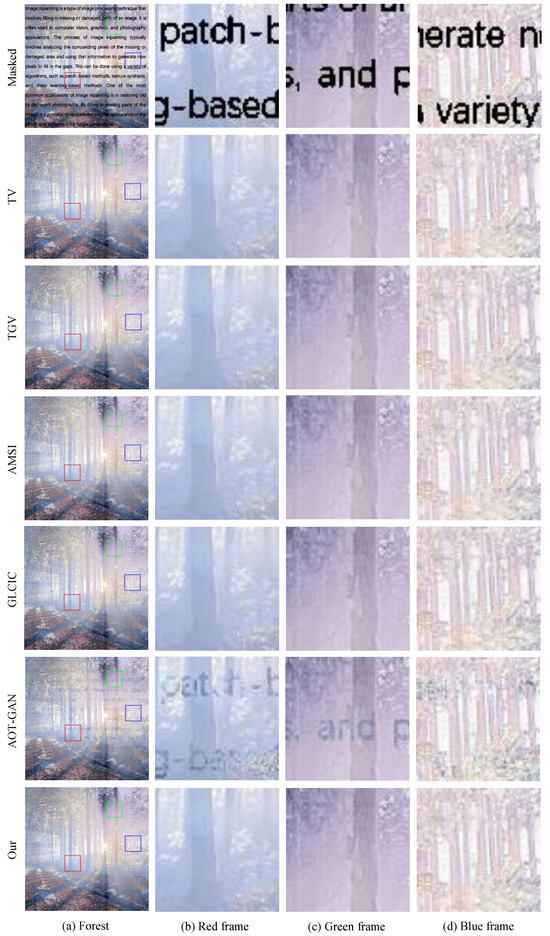

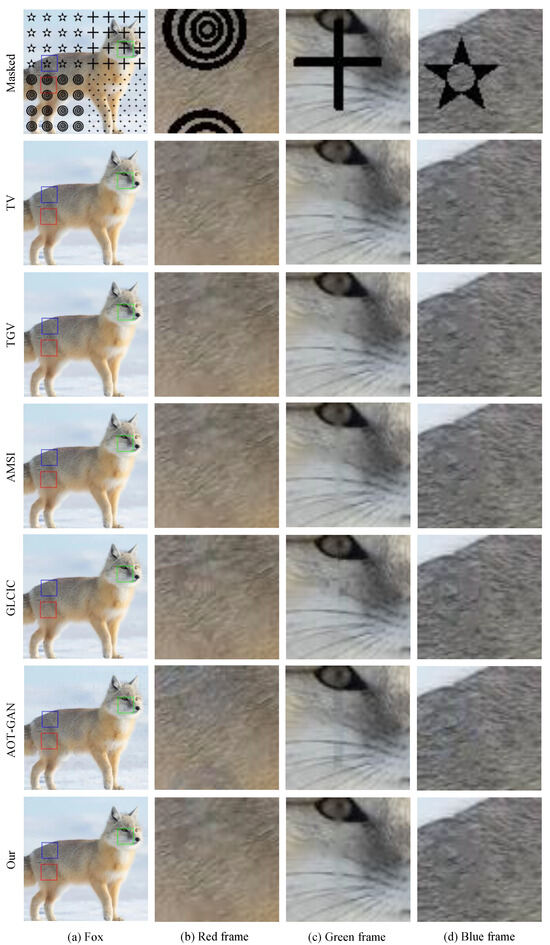

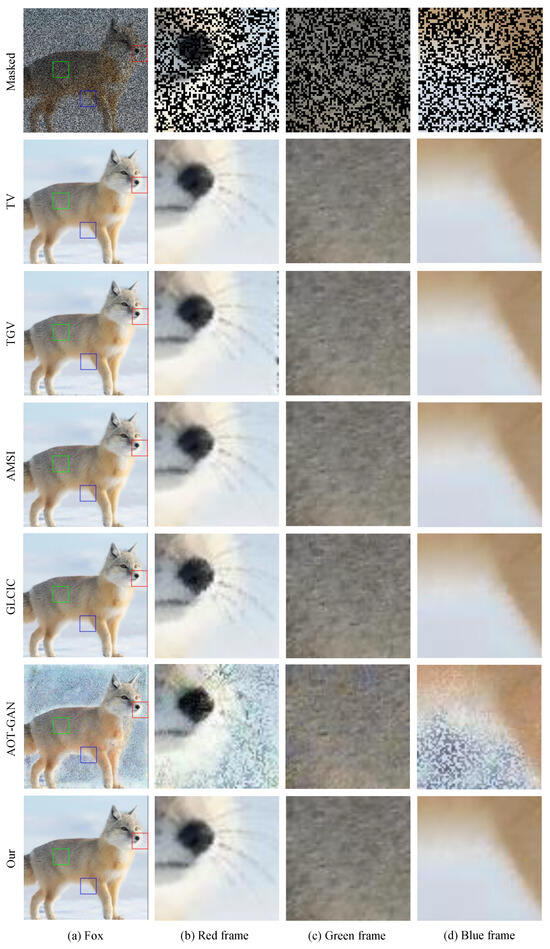

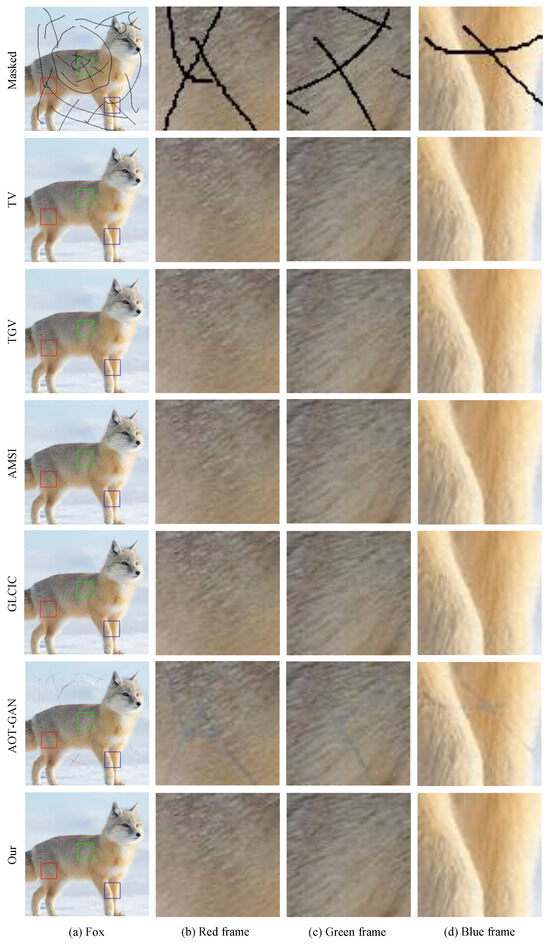

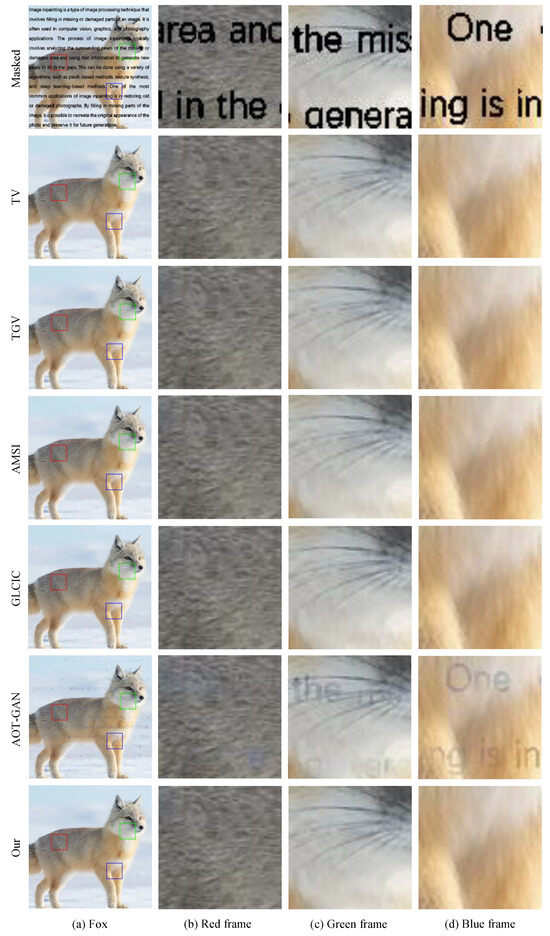

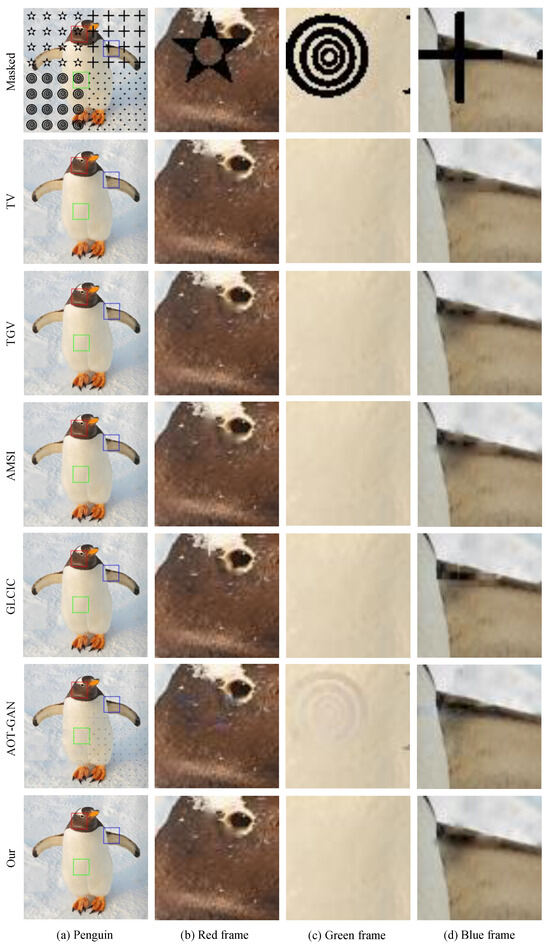

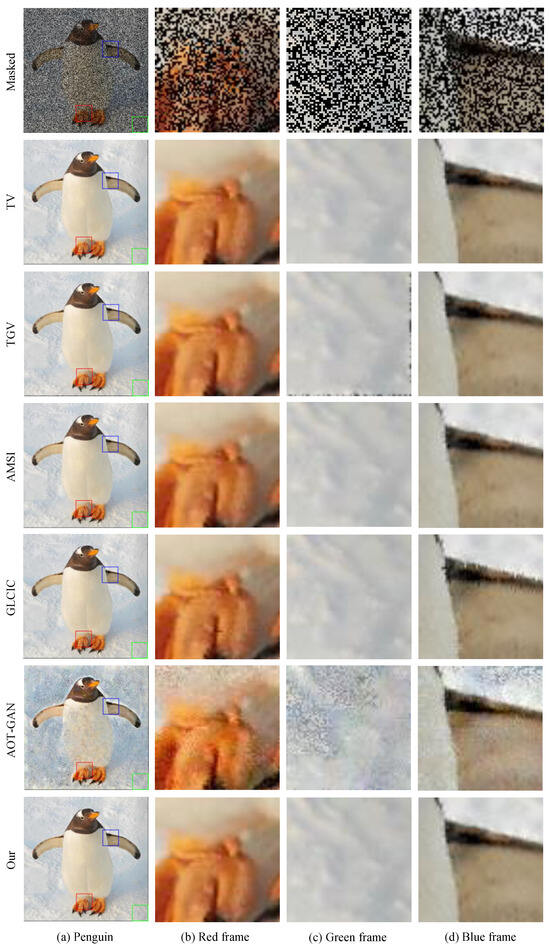

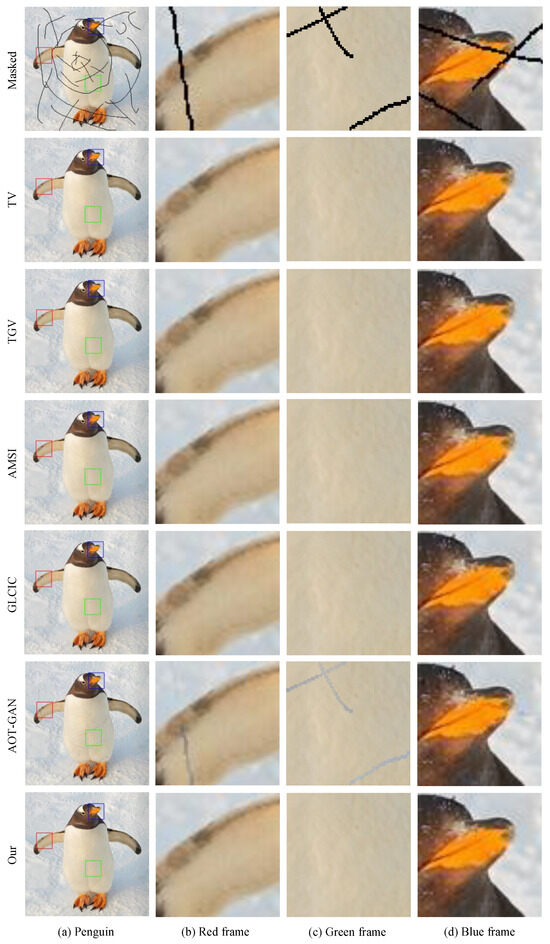

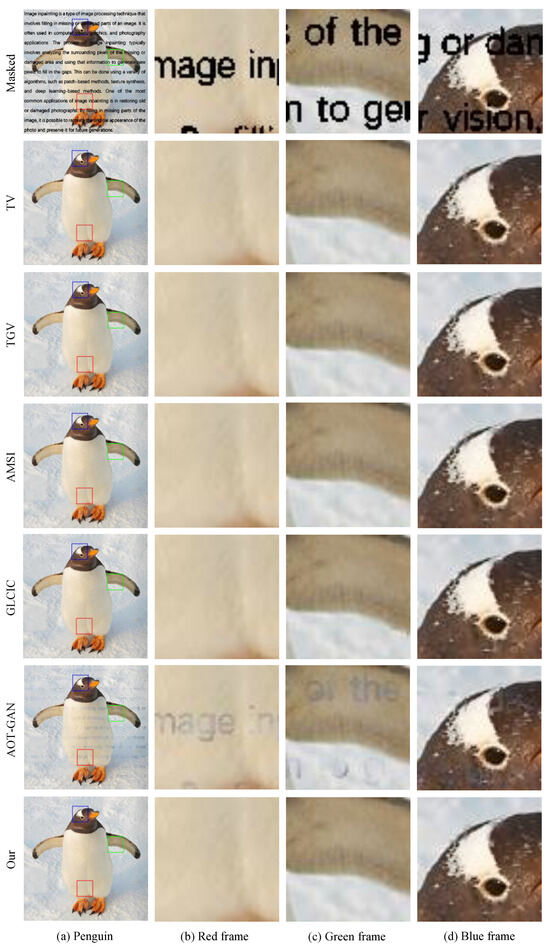

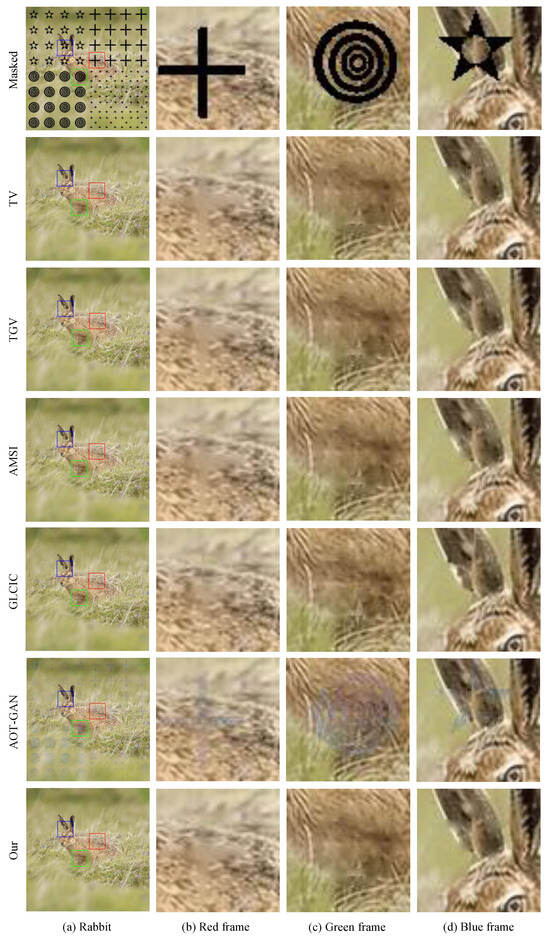

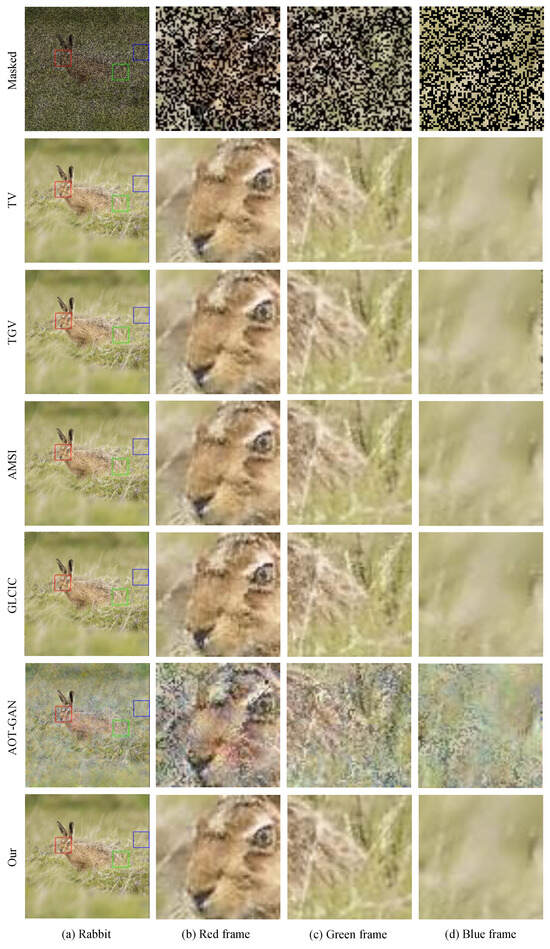

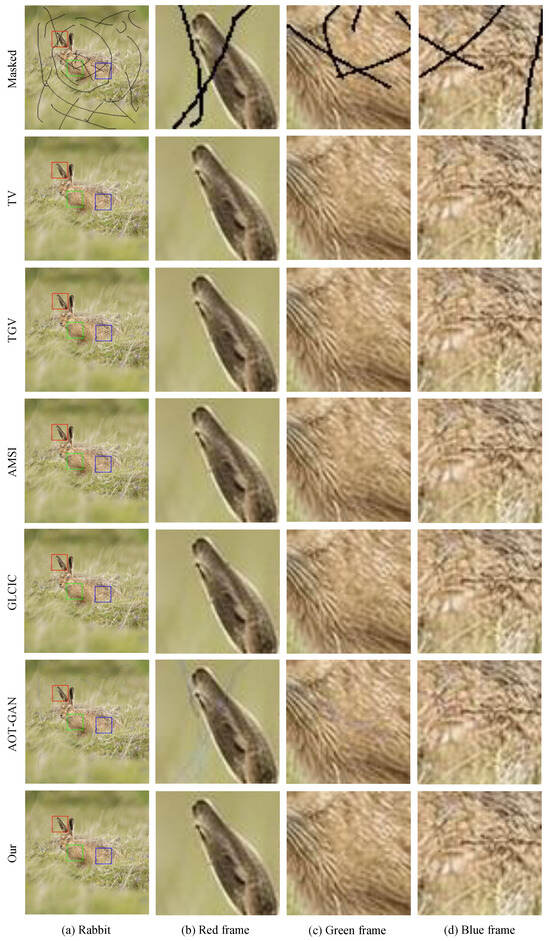

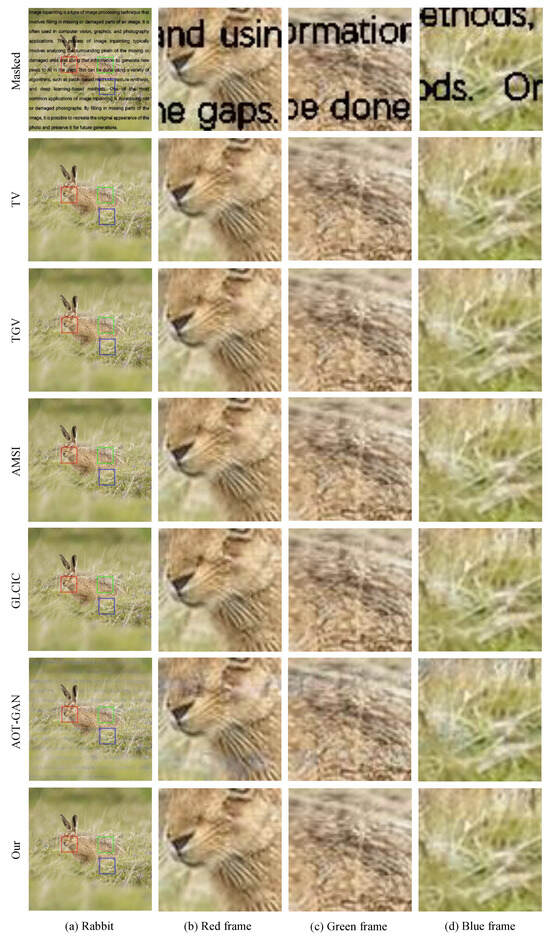

In the inpainting problem, masks are applied directly to ground-truth images that are assumed to be noise-free. The results of our model and those of Total Variation (TV) [66], Total Generalized Variation (TGV) [67], Adaptive modified Mumford–Shah Inpainting (AMSI) [69], Globally and Locally Consistent Image Completion (GLCIC) [70] and Aggregated Contextual Transformations for High-Resolution Image Inpainting (AOT-GAN) [72] models all had been shown in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31. To enhance the visual impact, we incorporated multiple color-coded boxes to highlight the details.

Figure 4.

Examples of building image with mark recovery.

Figure 5.

Examples of building image with random recovery.

Figure 6.

Examples of building image with scratch recovery.

Figure 7.

Examples of building image with watermark recovery.

Figure 8.

Examples of cat image with mark recovery.

Figure 9.

Examples of cat image with random recovery.

Figure 10.

Examples of cat image with scratch recovery.

Figure 11.

Examples of cat image with watermark recovery.

Figure 12.

Examples of face image with mark recovery.

Figure 13.

Examples of face image with random recovery.

Figure 14.

Examples of face image with scratch recovery.

Figure 15.

Examples of face image with watermark recovery.

Figure 16.

Examples of forest image with mark recovery.

Figure 17.

Examples of forest image with random recovery.

Figure 18.

Examples of forest image with scratch recovery.

Figure 19.

Examples of forest image with watermark recovery.

Figure 20.

Examples of fox image with mark recovery.

Figure 21.

Examples of fox image with random recovery.

Figure 22.

Examples of fox image with scratch recovery.

Figure 23.

Examples of fox image with watermark recovery.

Figure 24.

Examples of penguin image with mark recovery.

Figure 25.

Examples of penguin image with random recovery.

Figure 26.

Examples of penguin image with scratch recovery.

Figure 27.

Examples of penguin image with watermark recovery.

Figure 28.

Examples of rabbit image with mark recovery.

Figure 29.

Examples of rabbit image with random recovery.

Figure 30.

Examples of rabbit image with scratch recovery.

Figure 31.

Examples of rabbit image with watermark recovery.

We can see that deep learning models are incapable of inpainting images from thin curve mask, and the random mask Figure 2b, will completely destroy the ability to recover. The advantage of deep learning models may be inpainting images from large areas of masks, because the traditional model cannot inpaint images when a large area of image information is missing; it needs to use the surrounding information to know what the pixel value is in the masked area.

We can clearly see in the cat masked mark in the Figure 8 that our model based on the Fractional Laplacian operator can recover the masked image on hair details better than other traditional models like Total Variation (TV) [66], Total Generalized Variation (TGV) [67], and Adaptive modified Mumford-Shah Inpainting (AMSI) [69]; meanwhile, those models cannot recover a random mask in the edge of the image. All the results on PSNR and SSIM are shown on Table 2.

Table 2.

Image inpainting comparison results in terms of PSNR and SSIM.

4.3. Comparison of Calculation Time

In practical applications, in addition to the inpainting result, the time required for inpainting is also an indicator for evaluating the algorithm’s superiority. For traditional algorithms, most algorithms require many iterations of computation, while deep learning algorithms generally need a short processing time through the neural network. However, in reality, the most time-consuming part of deep learning methods is during the training phase, sometimes taking several hours, days, or even weeks. The time required to process a single image is related to the mask, and the results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Image inpainting comparison results in terms of time.

The computational time of the deep learning method is much lower than the traditional mathematical models, but if we consider the training time, traditional models still have significant advantages.

4.4. Inpainting and Denoising

To show the ability in inpainting and denoising of our model, we add some different types of noise to all images in Figure 1. We use seven kinds of noise as follows:

- Exponential Noise: The probability distribution function of exponential noise is

- Gamma Noise: The probability distribution function of gamma noise is

- Gaussian Noise: The probability distribution function of Gaussian noise is

- Poisson Noise: The probability distribution function of Poisson noise is:

- Rayleigh Noise: The probability distribution function of Rayleigh noise is

- Salt-and-Pepper Noise: The probability distribution function of salt-and-pepper noise is

- Uniform Noise: The probability distribution function of uniform noise is

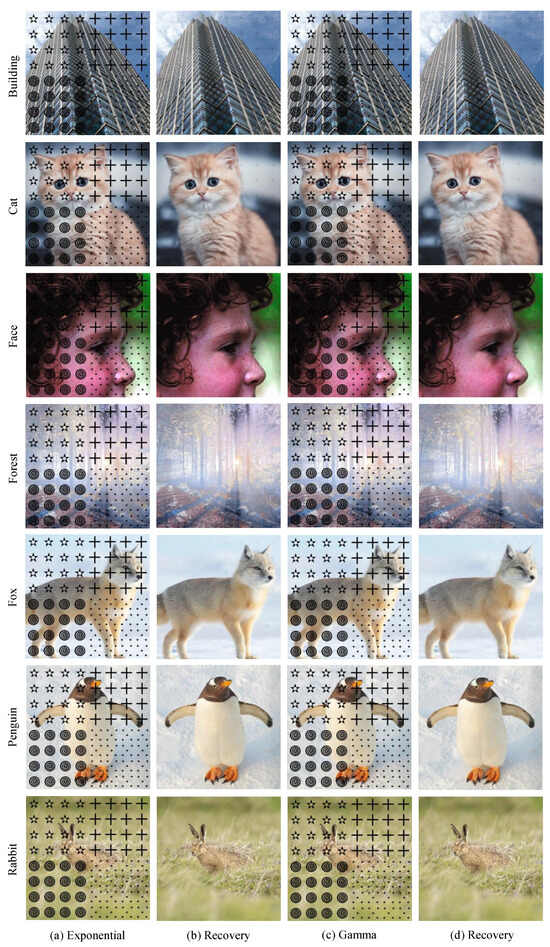

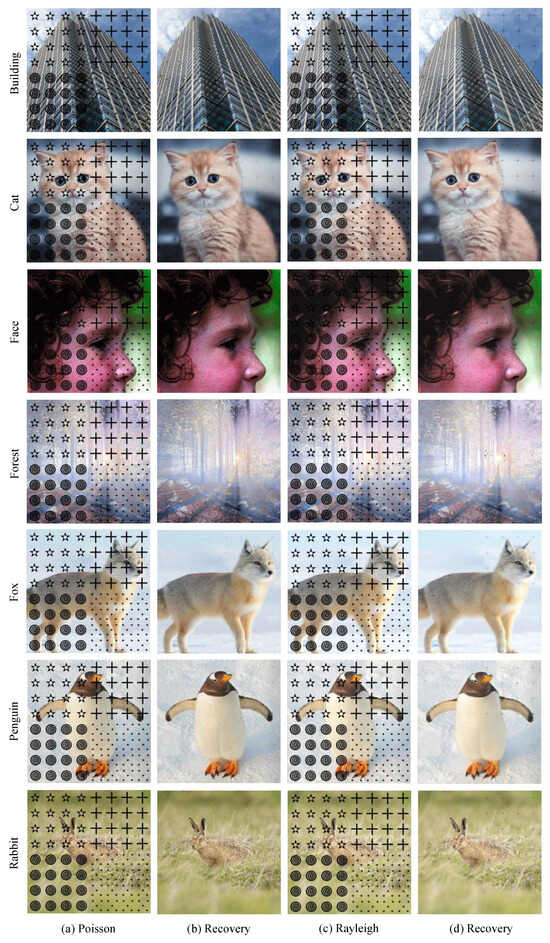

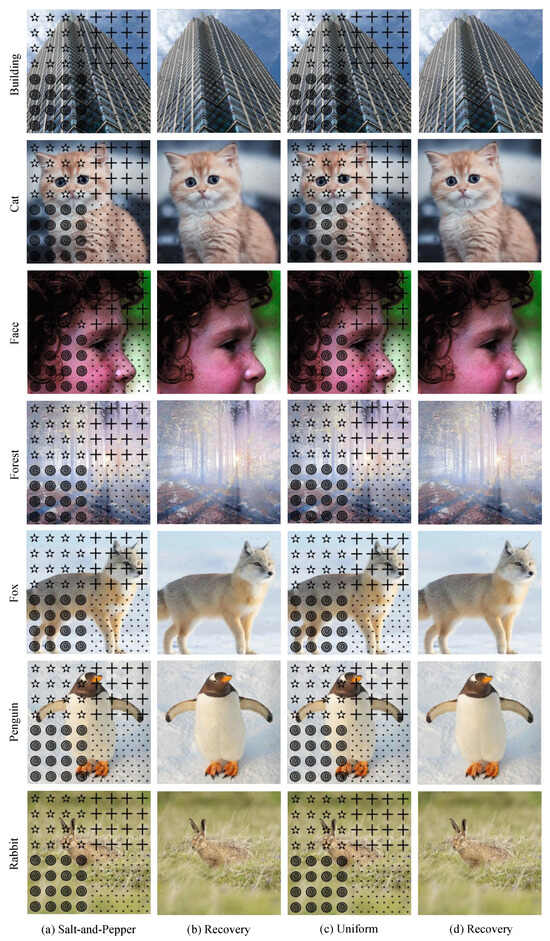

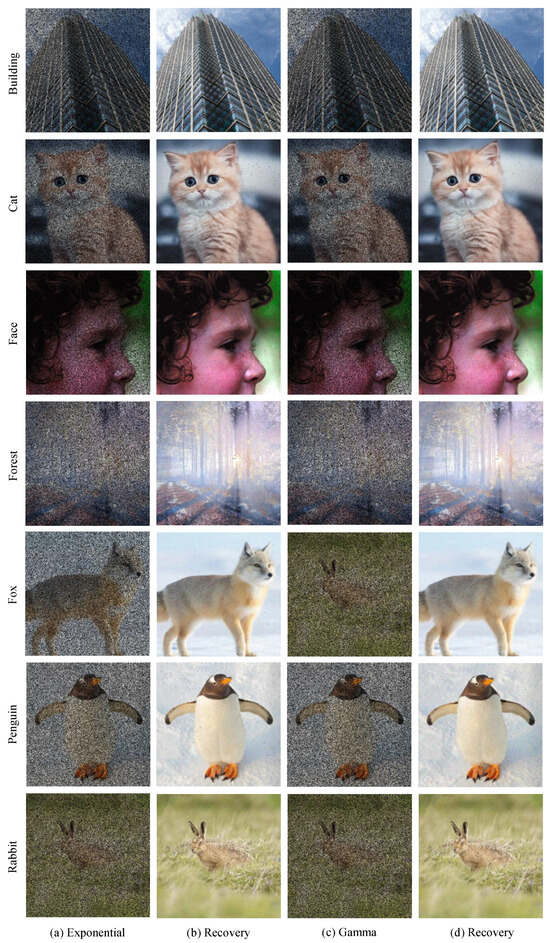

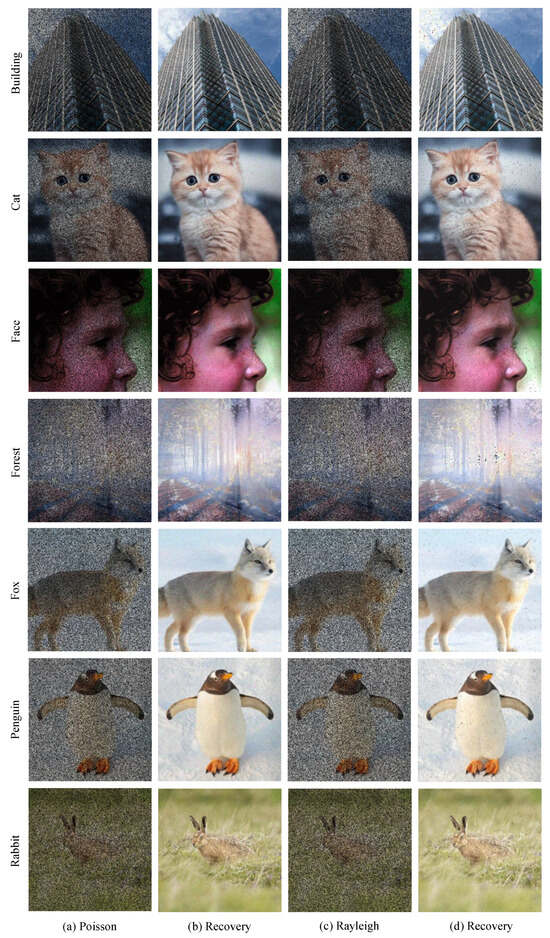

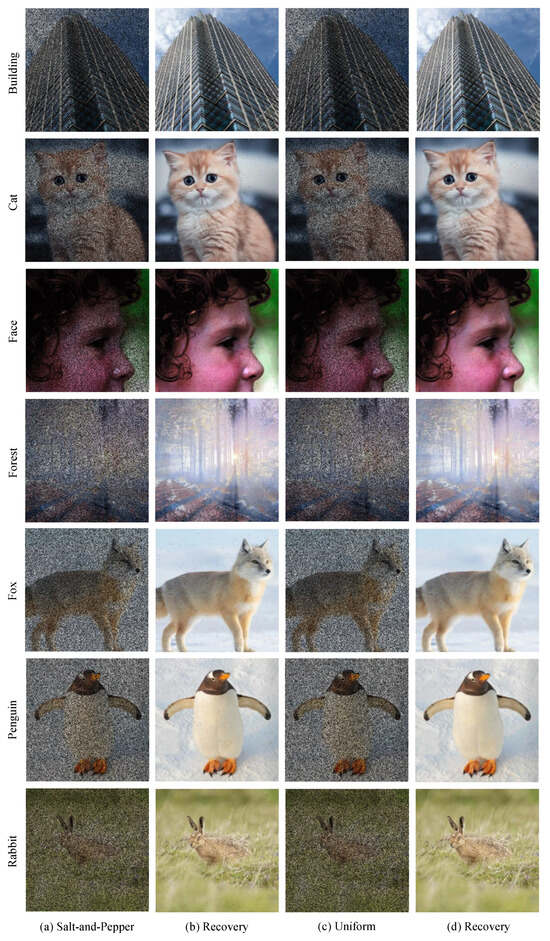

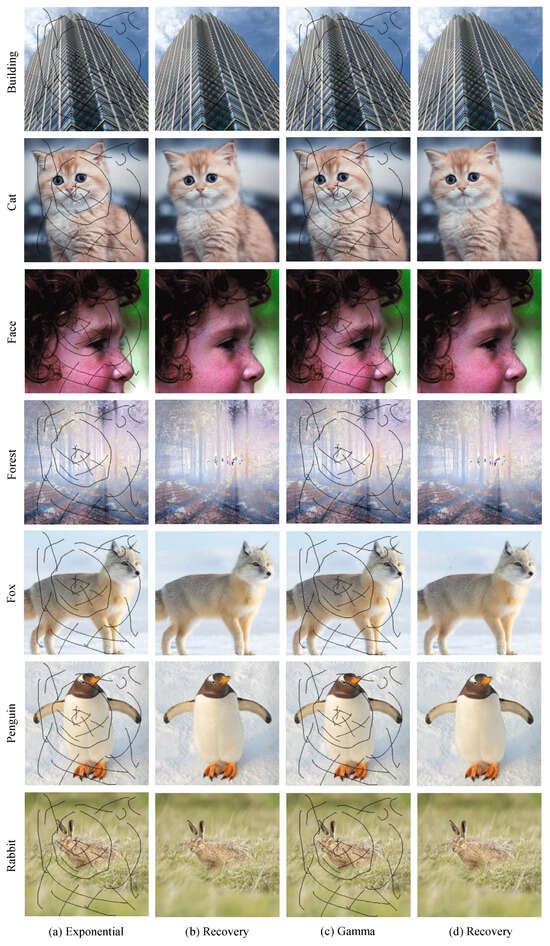

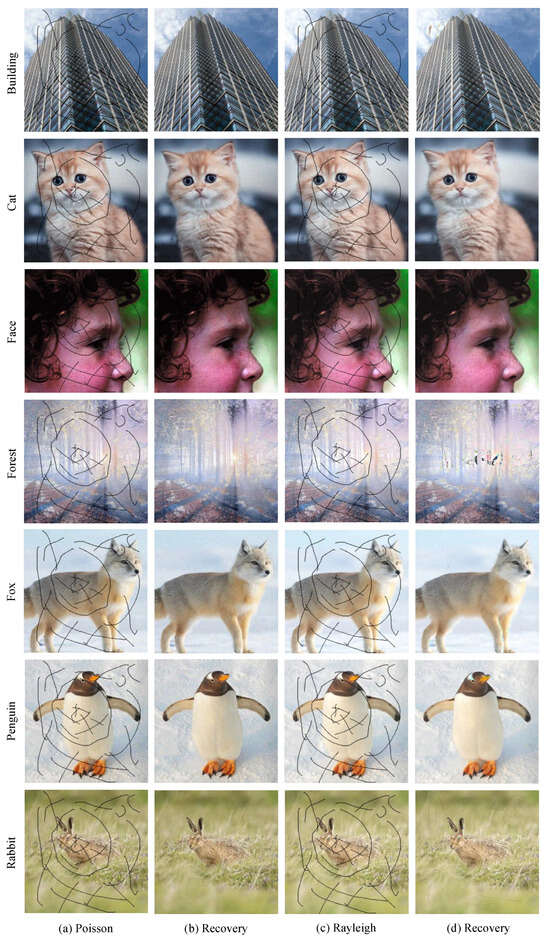

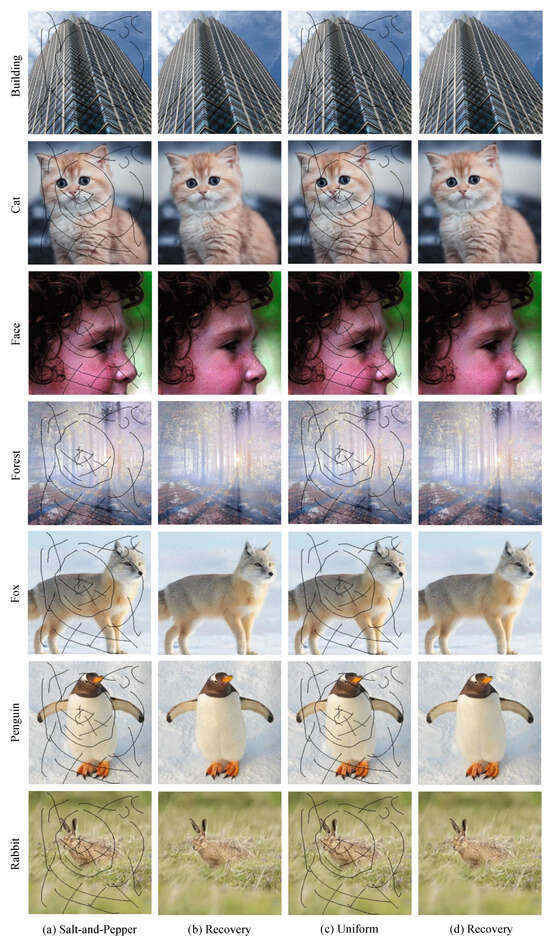

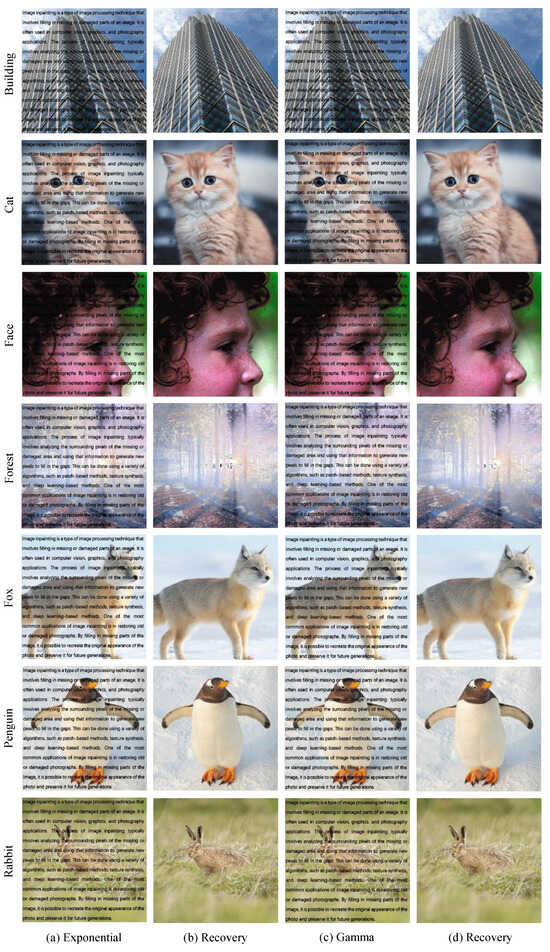

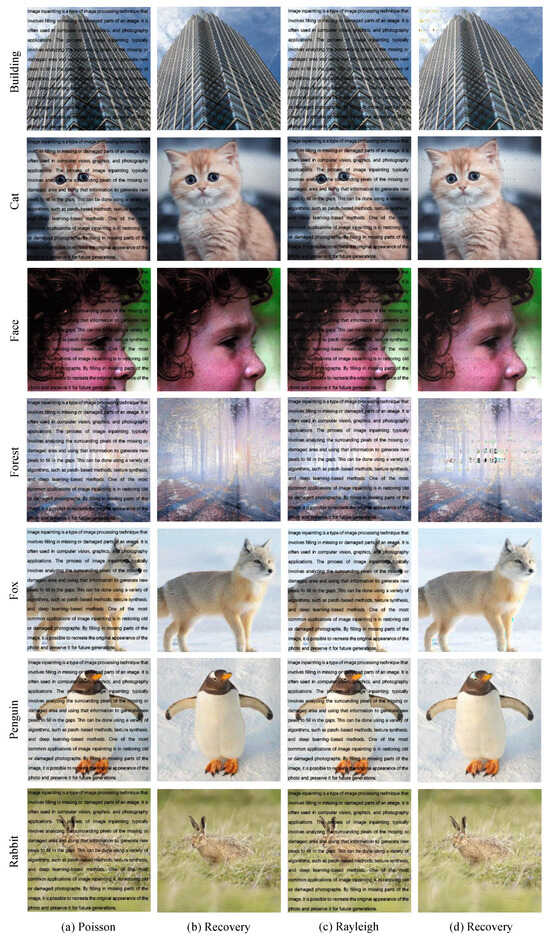

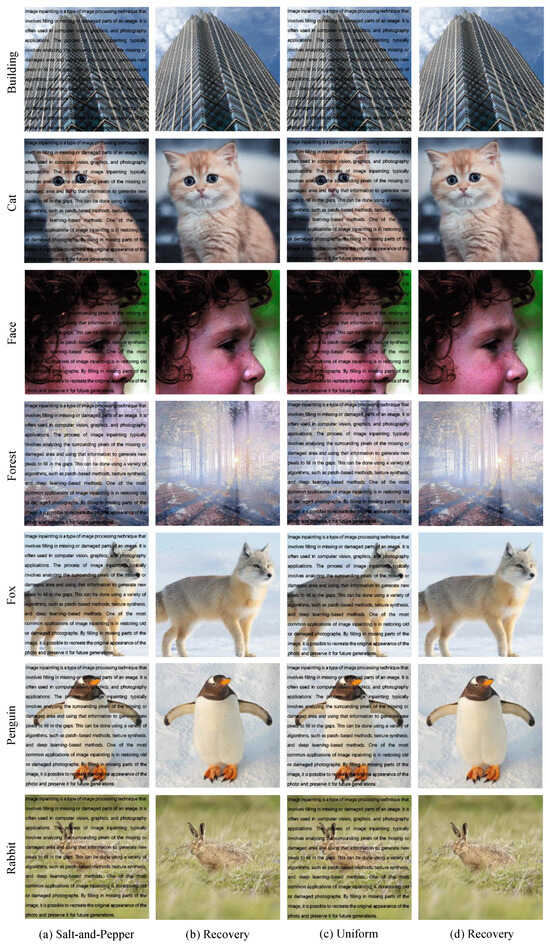

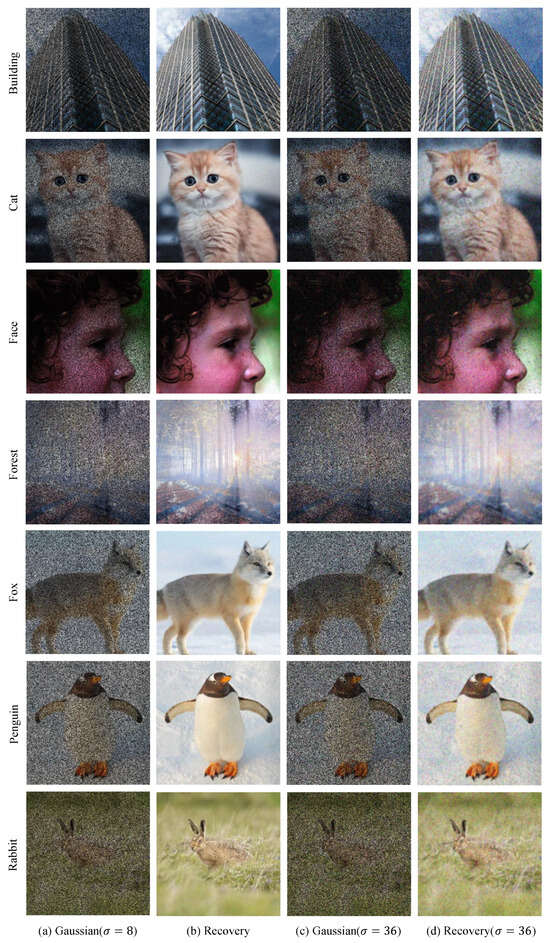

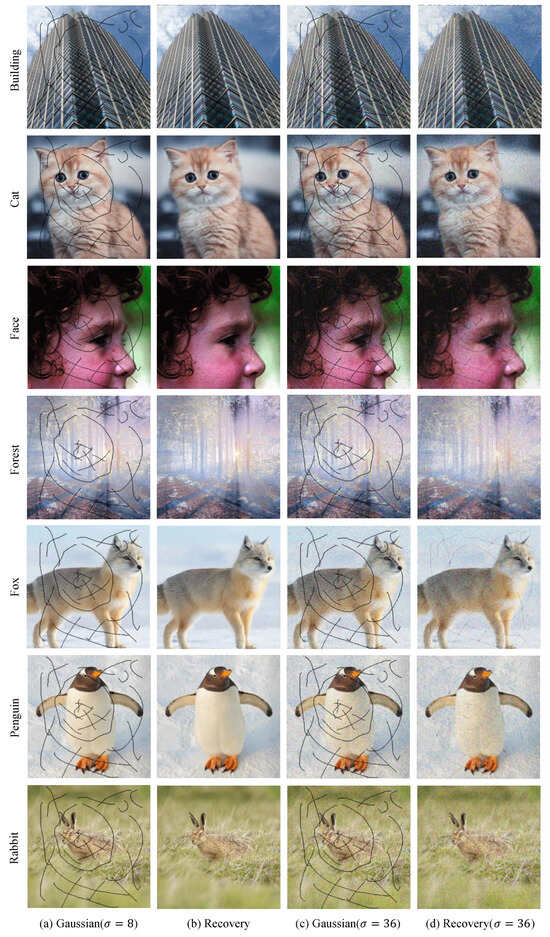

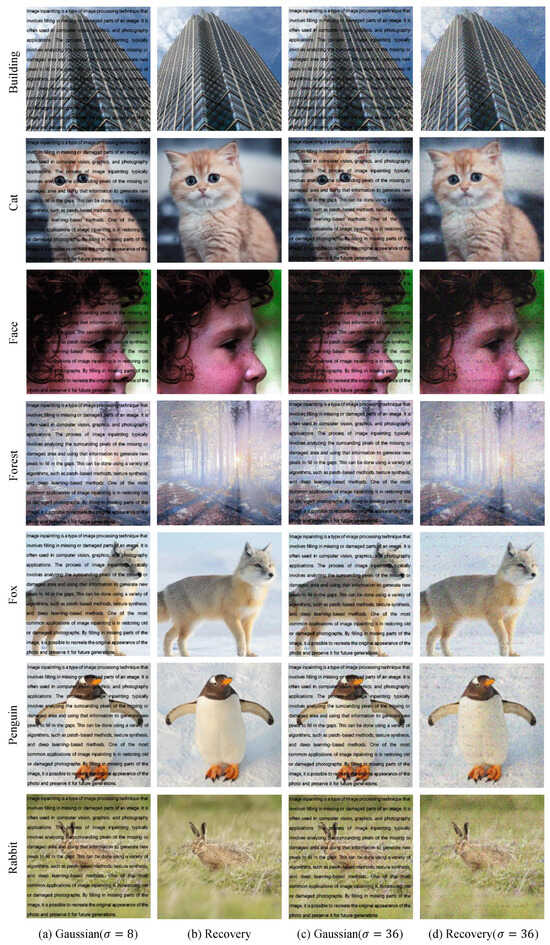

Table 4 shows the PSNR and SSIM results of Algorithm 3 in inpainting and denoising. Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34, Figure 35, Figure 36, Figure 37, Figure 38, Figure 39, Figure 40, Figure 41, Figure 42 and Figure 43 show the recovered noised image in using norm. We have the same result with Osher [43] that using norm instead of norm can have a better result in inpainting and denoising. It shows that our method can recover the destroyed image and reduce noise at the same time.

Table 4.

Inpainting results for images with denoising in additive noise.

Figure 32.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask mark in exponential noise and Gamma noise.

Figure 33.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask mark in Poisson noise and Rayleigh noise.

Figure 34.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask mark in salt-and-pepper noise and uniform noise.

Figure 35.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask random in exponential noise and Gamma noise.

Figure 36.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask random in Poisson noise and Rayleigh noise.

Figure 37.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask random in salt-and-pepper noise and uniform noise.

Figure 38.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask scratch in exponential noise and Gamma noise.

Figure 39.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask scratch in Poisson noise and Rayleigh noise.

Figure 40.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask scratch in salt-and-pepper noise and uniform noise.

Figure 41.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask watermark in exponential noise and Gamma noise.

Figure 42.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask watermark in Poisson noise and Rayleigh noise.

Figure 43.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask watermark in salt-and-pepper noise and uniform noise.

In Figure 40, we can see the noise has been reduced and mask area has been repaired. The effect of our algorithm can be seen easily.

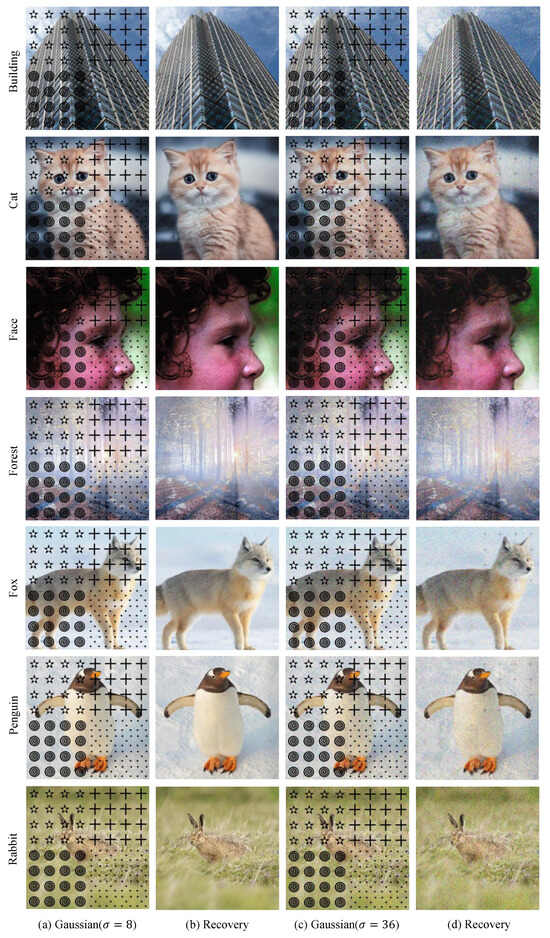

We observed that norm can better separate oscillatory components from high-frequency components compared to the norm, while also being better at removing noise while preserving edges. To show that this improvement can bring a better result, we add Gaussian noise with mean , standard deviation , and to all images in Figure 1. Table 5 and Table 6 show the PSNR and SSIM results of Algorithm 3, comparing norm with norm in inpainting and denoising. Figure 44, Figure 45, Figure 46 and Figure 47 show the recovered noised image in using norm. We have the same result with Osher [43] that using the norm instead of the norm can have a better result in inpainting and denoising. It shows that our method can recover the destroyed image and reduce noise at the same time.

Table 5.

Norm and comparison in inpainting and denoising with standard deviation .

Table 6.

Norm and comparison in inpainting and denoising with standard deviation .

Figure 44.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask mark in Gaussian noise.

Figure 45.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask random in Gaussian noise.

Figure 46.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask scratch in Gaussian noise.

Figure 47.

Examples of image inpainting and denoising with mask watermark in Gaussian noise.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we present an improved model based on the fractional Laplacian operator, which employs the norm of the fractional Laplacian operator as a regularization term and the norm as a fidelity term; these improvements lead to better results in restoring damaged regions. The introduction of an intermediate variable to the diffusion equations resolves the difficulty in handling term.

However, in the theoretical proof process, it is noted that the fractional Bessel potential space with is not a Banach space under the same norm definition, nor is it reflexive or separable. Since relevant theoretical research in this area is still ongoing, we have not extended our existence and uniqueness theorem to the case of . Consistently, our experiments demonstrate that as a parameter for image inpainting yields unsatisfactory performance. Given that the constraint at induces sparse solutions, there may be some special cases where better outcomes could be achieved. Therefore, future work should specifically investigate whether similar results hold for .

Model analysis confirms that our method is both theoretically sound and effective, with guaranteed convergence to the solution. Comparative experiments show that it consistently outperforms traditional models in preserving texture details and surpasses deep learning approaches in recovering thin curve masks. To further improve performance, we propose three potential strategies: (1) replacing deep learning methods with our approach for solving the diffusion equation, (2) using our energy functional as the loss function for network training, and (3) designing a hybrid pipeline where deep models handle large missing regions and our method refines fine structures. Such a combination strategy significantly enhances inpainting quality.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel image inpainting framework based on minimizing an energy functional that integrates an -norm regularization term involving fractional-order Laplacian operators with an -norm fidelity term. The model is theoretically grounded via an associated diffusion equation whose solution converges to the variational minimizer, with convergence rigorously justified. A finite difference-based numerical scheme is derived from the diffusion formulation and is systematically evaluated through comprehensive experiments. Comparative studies against classical variational methods and deep learning models demonstrate the proposed method’s superior performance in preserving structural details and suppressing noise under various degradation scenarios.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.Y., Z.-A.Y. and D.H.; Computational Implementation, W.S.; Validation, W.S.; Formal analysis, W.S. and H.Y.; Resources, H.Y.; Writing—original draft, W.S.; Writing—review and editing, H.Y. and X.L.; Supervision, Z.-A.Y. and D.H.; H.Y. and W.S. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Grant Number 2020YFA0712500; the Research and Development Project of Pazhou Lab (Huangpu), Grant Number 2023K0601; and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province, Grant Number 2024QK2006.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our deepest gratitude to LIU Qiang, HUANG Jingchi, and ZHOU Yulong for their contributions to the analytical framework of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bertalmio, M.; Sapiro, G.; Caselles, V.; Ballester, C. Image Inpainting. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–28 July 2000; pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Perona, P.; Malik, J. Scale-space and Edge Detection Using Anisotropic Diffusion. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1990, 12, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catté, F.; Lions, P.L.; Morel, J.M.; Coll, T. Image Selective Smoothing and Edge Detection by Nonlinear Diffusion. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1992, 29, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.F.; Shen, J. Variational Image Inpainting. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. J. Issued Courant Inst. Math. Sci. 2005, 58, 579–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadili, M.J.; Starck, J.L.; Murtagh, F. Inpainting and Zooming Using Sparse Representations. Comput. J. 2009, 52, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, M.; Lundervold, A.; Tai, X.C. Noise Removal Using Fourth-order Partial Differential Equation with Applications to Medical Magnetic Resonance Images in Space and Time. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2003, 12, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lim, H. Fourth-order Partial Differential Equations for Effective Image Denoising. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. (EJDE) 2009, 2009, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.H. Adaptive Fourth Order Partial Differential Equation Filter From the Webers Total Variation for Image Restoration. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 475, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Feng, X.C. Fractional-order Anisotropic Diffusion for Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, Y.F.; Hu, J.R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhou, J.L. Efficient CT Metal Artifact Reduction Based on Fractional-order Curvature Diffusion. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2011, 2011, 173748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Xue, D. Fractional-order total variation image restoration based on primal-dual algorithm. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2013, 2013, 585310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, K. A total fractional-order variation model for image restoration with nonhomogeneous boundary conditions and its numerical solution. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2015, 8, 2487–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhou, S.; Siddique, M.A. Fractional nonlinear anisotropic diffusion with p-Laplace variation method for image restoration. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2016, 75, 4505–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Z. Image Restoration: Wavelet Frame Shrinkage, Nonlinear Evolution PDEs, and Beyond. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2017, 15, 606–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, J. Fraction-order total variation blind image restoration based on L1-norm. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 51, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tian, X.; Jin, Q.; Hirasawa, K. Adaptive fractional-order total variation image restoration with split Bregman iteration. ISA Trans. 2018, 82, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z. On a fractional reaction–diffusion system applied to image decomposition and restoration. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 78, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridevi, G.; Srinivas Kumar, S. Image inpainting based on fractional-order nonlinear diffusion for image reconstruction. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 38, 3802–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaf, M.; Akram, G. Effects of fractional order derivative on the solution of time-fractional Cahn–Hilliard equation arising in digital image inpainting. Indian J. Phys. 2021, 95, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Ni, G.; Zeng, T. Image restoration based on fractional-order model with decomposition: Texture and cartoon. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 40, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouasnouane, O.; Moussaid, N.; Boujena, S.; Kabli, K. A nonlinear fractional partial differential equation for image inpainting. Math. Model. Comput. 2022, 9, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, J.A.; Khan, A.; Rahman, Z. Image restoration with fractional-order total variation regularization and group sparsity. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Fu, Q.; Su, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Yao, Z.A. The Fractional Laplacian Based Image Inpainting. Inverse Probl. Imaging 2024, 18, 326–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Shao, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, B. Variable-order fractional 1-Laplacian diffusion equations for multiplicative noise removal. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2024, 27, 3374–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, D. A non-convex fractional-order differential equation for medical image restoration. Symmetry 2024, 16, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ullah, A.; Fu, Z.J.; Khan, S.; Khan, S. Image restoration via combining a fractional order variational filter and a TGV penalty. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 60393–60418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y. Non-convex Fractional-order TV Model for Image Inpainting. Multimed. Syst. 2025, 31, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, A.; Rohim, A.; Kumar, B.; Saha, R. A fractional image inpainting model using a variant of Mumford-Shah model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminisi, A.; Pérez, P.; Toyama, K. Region Filling and Object Removal by Exemplar-based Image Inpainting. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komodakis, N.; Tziritas, G. Image Completion Using Efficient Belief Propagation via Priority Scheduling and Dynamic Pruning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2007, 16, 2649–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, J. Image Inpainting by Patch Propagation Using Patch Sparsity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2010, 19, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Newson, A.; Almansa, A.; Gousseau, Y.; Pérez, P. Non-local Patch-based Image Inpainting. Image Process. Line 2017, 7, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.; Regier, J.; Jordan, M.I.; Yosef, N. Information Constraints on Auto-encoding Variational Bayes. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing System, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Reda, F.A.; Shih, K.J.; Wang, T.C.; Tao, A.; Catanzaro, B. Image Inpainting for Irregular Holes Using Partial Convolutions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Shechtman, E.; Lu, H. High-resolution Image Inpainting with Iterative Confidence Feedback and Guided Upsampling. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XIX 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Mo, Q.; Lin, S.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Chen, H.; Xing, W.; Lu, D. Uctgan: Diverse Image Inpainting Based on Unsupervised Cross-space Translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5741–5750. [Google Scholar]

- Lischke, A.; Pang, G.; Gulian, M.; Song, F.; Glusa, C.; Zheng, X.; Mao, Z.; Cai, W.; Meerschaert, M.M.; Ainsworth, M.; et al. What is the Fractional Laplacian? A Comparative Review with New Results. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 404, 109009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, W.; Deng, G.; Liu, B. Discrete Laplacian Operator and Its Applications in Signal Processing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 89692–89707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, J.C.; García-Sáez, G. Bessel Potential Spaces and Complex Interpolation: Continuous Embeddings. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.04310. [Google Scholar]

- Osher, S.; Solé, A.; Vese, L. Image Decomposition and Restoration Using Total Variation Minimization and the H1. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2003, 1, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipierro, S.; Ros-Oton, X.; Valdinoci, E. Nonlocal problems with Neumann boundary conditions. Rev. Mat. Iberoam. 2017, 33, 377–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, R.E. Monotone Operators in Banach Space and Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations; American Mathematical Soc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, F.; Turner, I. Numerical methods for fractional partial differential equations with Riesz space fractional derivatives. Appl. Math. Model. 2010, 34, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, M.; Manafian, J.; Saadatmandi, A. Solving nonlinear fractional partial differential equations using the homotopy analysis method. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. Int. J. 2010, 26, 448–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, N.J.; Xiao, J.; Yan, Y. A finite element method for time fractional partial differential equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2011, 14, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, B.; Colorado, E.; De Pablo, A.; Sánchez, U. On some critical problems for the fractional Laplacian operator. J. Differ. Equ. 2012, 252, 6133–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musina, R.; Nazarov, A.I. On fractional laplacians. Commun. Partial Differ. Equ. 2014, 39, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Pu, X.; Huang, F. Fractional Partial Differential Equations and Their Numerical Solutions; World Scientific: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhuang, P.; Liu, Q. Numerical Methods of Fractional Partial Differential Equations and Applications; Science Press, LLC: Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.; Huang, G.; Li, C. The maximum principles for fractional Laplacian equations and their applications. Commun. Contemp. Math. 2017, 19, 1750018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozrikidis, C. The Fractional Laplacian; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Chen, A. Numerical methods for fractional partial differential equations. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2018, 95, 1048–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.A.; Zhou, Y.L. High order approximation for the Boltzmann equation without angular cutoff under moderately soft potentials. Kinet. Relat. Models 2020, 13, 435–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, P. The Fractional Laplacian; World Scientific: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Guo, B. Existence of solutions and Hyers–Ulam stability for a coupled system of nonlinear fractional differential equations with p-Laplacian operator. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Huang, J.; Wen, L.; Zhuang, S. Modeling viscoacoustic wave propagation using a new spatial variable-order fractional Laplacian wave equation. Geophysics 2021, 86, T487–T507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Derakhshan, M.H.; Askari, H. Distributed order fractional diffusion equation with fractional Laplacian in axisymmetric cylindrical configuration. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 113, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, M.; Laamri, E.H. Fractional Laplacians: A short survey. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.—S 2022, 15, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Yao, Z.A. Local existence for the non-resistive magnetohydrodynamic system with fractional dissipation in the Lp framework. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. 2022, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.V.d.C.; Zuo, J.; O’Regan, D. The Nehari manifold for a ψ-Hilfer fractional p-Laplacian. Appl. Anal. 2022, 101, 5076–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthagaray, J.P.; Nochetto, R.H. Besov regularity for the Dirichlet integral fractional Laplacian in Lipschitz domains. J. Funct. Anal. 2023, 284, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Derakhshan, M.H. On spectral polar fractional Laplacian. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 206, 636–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chan, T.F. Mathematical Models for Local Nontexture Inpaintings. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2002, 62, 1019–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredies, K.; Sun, H.P. Preconditioned Douglas–Rachford Algorithms for TV-and TGV-Regularized Variational Imaging Problems. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2015, 52, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, K.D.; Jiang, H. Enhanced Frequency-domain Optical Image Reconstruction in Tissues Through Total-variation Minimization. Appl. Opt. 1996, 35, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, D.N.H.; Surya, P.V.; Van Son, N.; Hieu, L.M. An Adaptive Image Inpainting Method Based on the Modified Mumford-Shah Model and Multiscale Parameter Estimation. Comput. Opt. 2019, 43, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, S.; Simo-Serra, E.; Ishikawa, H. Globally and Locally Consistent Image Completion. ACM Trans. Graph. (ToG) 2017, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, B.; Song, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, C. Rethinking Image Inpainting via a Mutual Encoder-Decoder with Feature Equalizations. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part II 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Fu, J.; Chao, H.; Guo, B. Aggregated Contextual Transformations for High-resolution Image Inpainting. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 29, 3266–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).