Abstract

Stagnation remains a persistent challenge in optimization with metaheuristic algorithms (MAs), often leading to premature convergence and inefficient use of the remaining evaluation budget. This study introduces , a novel meta-level strategy that externally monitors MAs to detect stagnation and adaptively partitions computational resources. When stagnation occurs, divides the optimization run into partitions, restarting the MA for each partition with function evaluations guided by solution history, enhancing efficiency without modifying the MA’s internal logic, unlike algorithm-specific stagnation controls. The experimental results on the CEC’24 benchmark suite, which includes 29 diverse test functions, and on a real-world Load Flow Analysis (LFA) optimization problem demonstrate that MsMA consistently enhances the performance of all tested algorithms. In particular, Self-Adapting Differential Evolution (jDE), Manta Ray Foraging Optimization (MRFO), and the Coral Reefs Optimization Algorithm (CRO) showed significant improvements when paired with MsMA. Although MRFO originally performed poorly on the CEC’24 suite, it achieved the best performance on the LFA problem when used with MsMA. Additionally, the combination of MsMA with Long-Term Memory Assistance (LTMA), a lookup-based approach that eliminates redundant evaluations, resulted in further performance gains and highlighted the potential of layered meta-strategies. This meta-level strategy pairing provides a versatile foundation for the development of stagnation-aware optimization techniques.

Keywords:

optimization; metaheuristics; stagnation; meta-level strategy; algorithmic performance; duplicate solutions MSC:

68W50

1. Introduction

The ability to adapt to the environment is crucial for the survival and success of living beings [1]. Humans surpass other living creatures in many ways, one of which is their capacity to optimize and utilize various tools to achieve optimization goals. Finding and implementing optimal solutions is a key factor behind humanity’s rapid and successful development [2]. Numerous optimization processes occur today without our awareness, spanning fields such as communications (where radio towers and message exchanges are modeled adaptively), logistics (where routes for goods and people are optimized), planning, production, drug manufacturing, and more. In short, optimization permeates nearly every aspect of our lives [3,4,5].

The advent of computers has enabled new approaches to solving real-world optimization problems. The first step is to model the problem in a way that lets us simulate its behavior using its key parameters. This representation, often termed a digital twin [6], aims to provide an expected or simulated state of the problem, given specific input parameters. The quality of this simulated state can then be evaluated against defined criteria. In optimization with evolutionary algorithms, this quality assessment is referred to as fitness. When developing a problem model, it is critical to define the level of detail required for the simulation to ensure the results are useful to the user. Excessive precision often yields no additional benefits, while demanding significant computational power and leading to time-consuming, costly software development [5].

A successful digital representation enables effective leveraging of modern computers’ computational power. Optimization involves identifying the best configuration of input parameters for the problem. While testing parameters may randomly yield improvements, this inefficient approach does not guarantee a local optimal solution within a limited timeframe. Conversely, examining all possible parameter combinations systematically is impractical due to the vast number of possibilities. This is where optimization algorithms, including MAs, become essential [7]. The behavior of MAs is a well-researched area, encompassing topics such as the influence of control parameters, and the mechanisms of exploration and exploitation during the search in the solution space [8,9,10].

Many MAs suffer from stagnation, where they fail to improve solutions over extended periods, often indicating entrapment in a local optimum [11]. This leads to wasteful function evaluations as MAs repeatedly explore the same search space regions without progress. Previous stagnation control is typically algorithm-specific [12], lacking universal applicability across diverse MAs. These limitations highlight a research gap in flexible, meta-level stagnation management that can enhance computational efficiency for any MA.

To address these gaps, we propose , a meta-approach that wraps any MA to enable self-adaptive search partitioning based on stagnation detection. activates at the meta-level only when stagnation occurs, reallocating resources to escape local optima efficiently, otherwise preserving the MA’s core behavior. Its universal applicability, synergy with , and evaluation on CEC’24 and LFA problems demonstrate its effectiveness.

The main contributions of this work are:

- A novel meta-approach, , for self-adaptive search partitioning based on stagnation detection. It wraps any MA, handling stagnation at the meta-level to enhance efficiency. activates only when stagnation is detected, otherwise allowing the MA to operate unchanged, ensuring broad applicability.

- Demonstration of meta-approach effectiveness by synergizing with . This strategy enhances exploration and exploitation across MAs without modifying their core mechanisms. Applying to showcases improved performance and supports versatile meta-strategy integration.

- Robust evaluation of the proposed approach using the CEC’24 benchmark and the LFA problem. Results show consistent performance improvements over baseline MAs, with novel insights into ABC and CRO behaviors.

This paper explores metaheuristic optimization systematically with a focus on mitigating stagnation in MAs. We begin by reviewing the background and related work on metaheuristic optimization and stagnation in Section 2, establishing the context for our contributions. Next, we present a novel meta-level strategy to address stagnation in Section 3, detailing its design and implementation. The proposed approach is evaluated empirically in Section 4, where its performance is assessed across diverse benchmark problems. We then analyze the findings and their implications in Section 5, providing a deeper understanding of the strategy’s impact. Finally, the paper concludes in Section 6, summarizing the key outcomes, and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Related Work

Parallel to the development of computing, significant advancements have occurred in computational applications for solving various optimization problems. For instance, as early as 1947, George Dantzig implemented the Simplex Algorithm to address the Diet Problem [13]. By 1950, techniques like Linear Programming were being applied to optimize logistical challenges, such as the Transportation Problem [14,15]. These efforts were followed by the development of optimization techniques, including Dynamic Programming, Integer Programming, Genetic Algorithms, and Simulated Annealing, applied to a wide range of optimization problems [16,17,18,19]. The period between 1980 and 1990 marked the beginning of a flourishing era for various optimization heuristics and metaheuristics. Techniques such as Tabu Search, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Differential Evolution (DE) emerged during this time [20,21,22,23,24].

Today, we are in an era characterized by an explosion of metaheuristic optimization algorithms and hybrid approaches [25,26,27,28]. Among the more popular approaches, metaheuristics can be categorized into evolutionary algorithms (EAs) and swarm intelligence (SI)-based methods. EAs include techniques such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Genetic Programming (GP), and DE. SI methods include techniques such as PSO, ACO, ABC, the Firefly Algorithm (FA), and Cuckoo Search (CS).

Optimization incurs a computational cost, which can be managed through stopping criteria [29]. Various approaches exist to define these criteria, including time limits, iteration counts, energy thresholds, function evaluation limits, and algorithm convergence. Among these, the most commonly used stopping criterion is the maximum number of function evaluations () [30,31], as function evaluations often represent the most computationally expensive aspect of optimization in real-world applications. In our experiments, we adopted as the stopping criterion. For this paper, the optimization process for a problem P is defined as the search for an optimal solution using an algorithm constrained by , as shown in Equation (1).

Stagnation

Stagnation is a well-known phenomenon in optimization algorithms [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. It occurs when an algorithm fails to improve the current best solution over an extended period of computation or time. Improvement can be quantified using the -stagnation radius, where represents the minimum required improvement for a solution to be considered enhanced [40], and a period before entering stagnation is defined by the threshold . This period can be measured by the number of iterations without improvement, elapsed time, or the number of function evaluations.

Researchers have proposed various strategies to overcome stagnation, ranging from simple restart mechanisms to more sophisticated adaptive strategies. In simple restart mechanisms, stagnation serves as an optimization stopping criterion, either to conserve computational resources or to extend optimization as long as improvements occur, thus avoiding premature termination due to fixed iteration limits or function evaluation budgets [29,41]. Alternatively, stagnation can be used as an internal mechanism to balance exploration and exploitation. In this context, stagnation triggers adaptive strategies—such as increasing diversity [42,43,44], restarting parts of the population [45,46], or modifying parameters [12,47,48]—to help the algorithm escape the local optima and enhance global search capabilities. For example, in [40], the authors proposed a hybrid PSO algorithm with a self-adaptive strategy to mitigate stagnation by adjusting the inertia weight and learning factors based on the stagnation period. Similarly, adapting the population size based on stagnation parameters is suggested in [49,50]. In Ant Colony System optimization, the authors of ref. [51] introduce an additional parameter, the distance function, to address stagnation. For PSO algorithms, ref. [52] incorporated a stagnation coefficient and Fuzzy Logic, while [53] proposed a diversity-guided convergence acceleration and stagnation avoidance strategy. A self-adjusting algorithm with stagnation detection based on a randomized local search was presented in [54]. More recent work adapts Differential Evolution (DE) with an adaptation scheme based on the stagnation ratio, using it as an indicator to adjust control parameters throughout the optimization process [55]. The authors of the MFO–SFR algorithm introduced the Stagnation Finding and Replacing (SFR) strategy, which detects and addresses stagnation using a distance-based method to identify stagnant solutions [56]. The CIR-DE method tackles DE stagnation by classifying stagnated solutions into global and local groups, employing chaotic regeneration techniques to guide exploration away from these individuals [57]. Self-adjusting mechanisms, including stagnation detection and adaptation strategies for binary search spaces, have been explored in [54,58].

The reviewed MAs often rely on internal stagnation controls, limiting their flexibility and efficiency across diverse algorithms. To address this, we propose , a meta-level approach that wraps any MA, detecting stagnation and adaptively partitioning computational resources.

3. Meta-Level Approach to Stagnation

This section introduces a novel meta-level strategy designed to address the stagnation problem in MAs. By leveraging stagnation detection, we propose a self-adaptive search partitioning mechanism that enhances the efficiency of computational resource utilization. The approach builds on the concept of MAs and introduces two key components: the strategy, which partitions the optimization process based on stagnation criteria, and its synergy with the approach, which uses memory to avoid redundant evaluations. These methods aim to improve the performance of MAs by mitigating the effects of stagnation, particularly in complex optimization landscapes.

3.1. Leveraging Stagnation for Self-Adapting Search Partitioning

Since we use as the stopping criterion, we define stagnation based on the number of function evaluations without improvement in the current best solution. This threshold, denoted , determines when the algorithm enters a stagnation cycle.

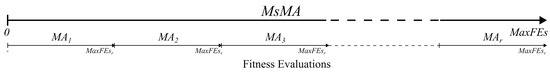

The simplest approach to handling stagnation is to execute the algorithm multiple times and select the best solution from each run using multi-start mechanisms. Due to the stochastic nature of these algorithms, multiple restarts in a single run enable the exploration of different regions of the search space. However, computational budgets impose constraints that dictate our stopping conditions. In this case, we adopted the established stopping criterion of . To apply multiple restarts while adhering to the overall stopping criterion , a basic run partitioning mechanism can be interpreted as distributing function evaluations across individual restarts. The simplest method is to allocate evaluations uniformly across restarts. For example, if we perform restarts, the stopping condition for each restart r is defined by Equation (2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Uniform partitioning as defined by Equation (2).

This uniform distribution of computational resources raises the question of whether a single, longer run or multiple shorter runs is more effective. In most scenarios, the answer depends on stagnation. For instance, if stagnation occurs, it often makes sense to distribute computational resources across multiple restarts. However, a challenge arises in defining stagnation precisely—specifically, after how many evaluations () can we consider stagnation to have occurred? Naturally, algorithms do not improve solutions with every evaluation, and the frequency of improvements typically decreases as the algorithm progresses. The optimal value depends on the problem type and the exploration mechanisms of the MA.

In the proposed meta-optimization approach, which incorporates internal adaptive search partitioning based on a stagnation mechanism (), we maintain as the primary stopping criterion, while serves as an internal stopping/reset condition within the algorithm. The parameter partitions each optimization run according to the algorithm’s stagnation criteria, where:

Here, r represents the number of stagnation phases the algorithm has encountered excluding the current run. If the algorithm does not enter a stagnation phase, then with .

In the worst-case scenario, such as when the first evaluation yields the best overall result, the maximum number of search partitions r is constrained by and , as expressed in Equation (4):

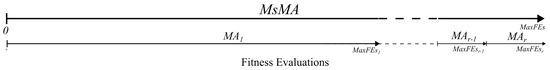

The best solution found in each partition is stored, and the overall best solution is returned as the final result (Equation (5), Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Partitioning based on stagnation as defined by Equation (5).

The key research question is whether this approach can enhance the performance of the selected MAs. In formal notation (Equations (6) and (7)), we aim to achieve:

where:

- denotes the expectation (average performance) over multiple optimization runs due to the stochastic nature of the algorithm.

- is a problem-dependent comparison operator, defined as:

MsMA Strategy: Implementation Details

To implement a meta-strategy for self-adaptive search partitioning at the meta-level, we propose using an algorithm wrapper that overrides execution. This strategy introduces an additional parameter, , used as an internal stopping criterion (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1. MsMA: A Meta-Level Strategy for Overcoming Stagnation |

|

The idea behind this approach is that the algorithm consumes as many function evaluations as needed until stagnation is detected. Upon stagnation, a new search is initiated with a reduced evaluation budget. The number of evaluations already used is subtracted from , effectively decreasing the budget for subsequent runs. The optimization ceases once all evaluations are exhausted.

3.2. Synergizing MsMA and LTMA for Improved Performance

LTMA is a meta-level approach that enhances performance by leveraging memory to avoid re-evaluating previously generated solutions, commonly known as duplicates [11]. When an MA generates a new solution, it is stored in the memory. If the same solution is encountered again, the algorithm skips its evaluation and reuses the previously computed fitness value, leaving the fitness evaluation counter unchanged. Since memory lookup is significantly faster than fitness evaluation—especially in real-world optimization problems—this approach improves the computational performance substantially. LTMA is particularly beneficial when an algorithm repeatedly generates already-evaluated solutions, such as during stagnation phases, where duplicates are a common issue. Stagnation may not occur at a single point but can involve wandering within a region [36].

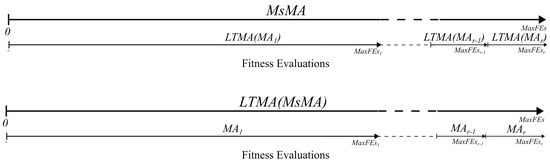

As a meta-level strategy, can be combined with another meta-level approach, LTMA, to leverage synergistic effects. LTMA prevents redundant evaluations of previously encountered solutions, enhancing performance and accelerating convergence. The approach can be applied in two ways: either to each MA partition run (Equation (8)) or to the entire approach (Equation (9)).

Figure 3 illustrates the application of the LTMA strategy to MsMA, as detailed in Equations (8) and (9), showing MaxFEs partitioning for the top and bottom configurations.

In the first approach (Equation (8)), LTMA is applied to each MA partition run, with a memory reset after each run, using the same or less memory compared to the second approach. In contrast, the second approach (Equation (9)) applies LTMA across all the partition runs , sharing information about previously explored areas between runs. This increases the likelihood of duplicate memory hits, as previously generated solutions remain in the LTMA memory.

The implementation of the approach is presented in Algorithm 2. This algorithm resembles the approach closely (Algorithm 1), with the addition of the wrapper, which enhances performance by leveraging memory to avoid re-evaluating previously generated solutions.

| Algorithm 2. LTMA(MsMA): Implementation Variant of MsMA Using LTMA |

|

As demonstrated in [11], modern computers have sufficient memory capacity for most optimization problems, storing only solutions and their fitness values. Therefore, we will evaluate the variant from Equation (9) in our experiments.

3.3. Time Complexity Analysis

Each meta-operator adds some overhead to the optimization process. The strategy checks for stagnation and resets the algorithm’s internal state, which can be done in constant time. The time complexity of is , as it performs only a few extra operations per function evaluation. Detecting stagnation adds minimal overhead, requiring a single if statement and a counter to check whether a new solution improves the current best.

The strategy has a higher cost. Its time complexity is , where n is the number of function evaluations. Each evaluation involves checking for duplicates and updating memory, operations that take constant time on average. As shown in the original LTMA study [11], this overhead is small and generally negligible. There are edge cases, however. One occurs when algorithms, such as RS, rarely generate duplicate solutions. Another arises when fitness evaluations are extremely fast—comparable to a memory lookup in LTMA. In such cases, using LTMA can be slower than running the algorithm without it.

4. Experiments

The primary objective of this research is to promote meta-approaches by investigating the phenomenon of stagnation and exploring a meta-approach to overcome it. To achieve this, we selected several MAs for single-objective continuous optimization, specifically from evolutionary algorithms (EA) and swarm intelligence (SI). The parameters of the selected algorithms are kept at their default settings rather than being optimized. It is crucial to emphasize that the focus of this research is not to identify the best-performing MA but to analyze the effects of stagnation and evaluate the proposed method, which does not modify the core functioning of the optimization algorithm directly.

The selected SI algorithms are: Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [59] with (where n denotes the problem dimensionality) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [23]. For EA, we selected: Self-Adapting Differential Evolution (jDE) [47], the less-known Manta Ray Foraging Optimization (MRFO) [60], and the Coral Reefs Optimization Algorithm (CRO) [61]. The source codes of all the algorithms used are included in the open-source EARS framework [62], specifically in the package. We also included a simple random search (RS) as a baseline algorithm in all the experiments (Equation (10)).

4.1. Statistical Analysis

Comparing stochastic algorithms requires complex statistical analysis involving multiple independent runs, average results, and Standard Deviations to determine significant differences. In practice, we aim for a simple representation of an algorithm’s performance, which can be achieved, for example, by assigning a rating to each algorithm. This approach is well-established and validated in fields such as chess ranking and video game matchmaking, where the goal is to pair opponents of similar strength [63,64,65,66]. Our experiments utilized the EARS framework with the default Chess Rating System for Evolutionary Algorithms (CRS4EA) [30,31]. CRS4EA integrates the Glicko-2 rating system, a widely used method in chess for ranking players. It assigns a rating to each algorithm based on its performance in benchmark tests, comparing the results against other algorithms in pairwise statistical evaluations—analogous to how chess players are ranked. CRS4EA operates by assessing algorithms based on their wins, draws, and losses in direct comparisons. These results determine each algorithm’s rating and confidence intervals. Every algorithm starts with a rating deviation (RD) of 350 and a rating of 1500, which is updated after each tournament. Over time, as the algorithm’s performance stabilizes, its RD is expected to decrease.

A study by [67] shows that the CRS4EA method performs on par with common statistical tests, like the Friedman test and the Nemenyi test. It also gives stable results, even with few independent runs. Another study by [68] finds CRS4EA comparable to the pDSC method. Together, these studies support CRS4EA as a reliable tool for comparing evolutionary algorithms.

To ensure reliable rating updates, it is recommended to set the minimum RD () based on the number of matches and players in the tournament. In classical game scenarios, where players compete less frequently, an of 50 is used typically. However, in our experiments, each MA competes against every other MA on 29 problems across 30 tournaments (requires, 30 independent runs for each problem), resulting in a high frequency of matches. Consequently, we set to the minimum recommended value of 20. Reducing below 20 is not advisable, as it may cause the ratings to converge too slowly [69,70]. We derived confidence intervals to compare algorithm performance using the computed ratings and RD values. The statistical significance of differences between algorithms is determined by the overlap (or lack thereof) of confidence intervals, calculated as around each algorithm’s rating. Non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference between algorithms with 95% confidence [69].

4.2. Benchmark Problems

Evaluating and comparing the performance of optimization algorithms requires a well-defined set of benchmark problems. Selecting a representative set that captures diverse optimization challenges ensures a fair and meaningful comparison. CEC benchmarks are used widely in the optimization community due to their extensive documentation and established credibility, making them suitable for our experiments. To prevent algorithms from exploiting specific problem characteristics, the benchmark problems are shifted and rotated, ensuring a more robust evaluation [71,72].

For our experiments, we utilized the latest CEC’24 benchmark suite [73], specifically the Single Bound Constrained Real-Parameter Numerical Optimization benchmark. This suite comprises 29 problems, including 2 unimodal, 7 multimodal, 10 hybrid, and 10 composition functions, designed to simulate various optimization challenges. The CEC’24 benchmark provides a comprehensive evaluation of optimization algorithms across a diverse range of problems.

4.3. MsMA: Meta-Level Strategy Experiment

For the evaluation of , we utilized the CEC’24 benchmark suite for the selected MAs, employing the CRS4EA rating system for ranking. In our experimental setup, we set the dimensionality of the problems to , and defined the maximum number of function evaluations () according to the benchmark specifications as .

To evaluate the meta-approach, we addressed the experimental question: How does the introduction of the MsMA strategy influence the performance of MAs? This raises an additional question with the introduction of the new parameter : How does the MinSFEs parameter influence algorithm performance?

To investigate this, we tested values at 2%, 4%, and 10% of , corresponding to 6000, , and evaluations, respectively. We labeled each algorithm using the strategy with suffixes _6, _12, and _30, reflecting the number of evaluations in thousands. For example, when configured with , the ABC algorithm is renamed ABC_6. Thus, an algorithm tested with different values is treated as a distinct algorithm within the CRS4EA rating system. As a result, the ABC algorithm appears in the tournament four times—once with its default settings, and three times with different values.

The experimental results are presented in a leaderboard table, displaying the ratings of MAs on the CEC’24 benchmark based on 30 tournament runs (requires, 30 independent runs for each problem). This setup is justified by previous findings showing that the CRS4EA rating system provides more reliable comparisons, and does not require a larger number of independent runs to achieve statistically robust results [67]. For each MA, we report its rank based on the overall rating, the rating deviation interval, the number of statistically significant positive (S+), and negative (S−) differences at the 95% confidence level (Table 1).

Table 1.

The MsMA Leaderboard on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

The strategy proved highly successful, as all the algorithms incorporating achieved higher ratings and ranks than their base variations (Table 1). However, not all the variations resulted in statistically significant differences. For example, while jDE_6 and jDE_30 showed significant improvements over the core jDE, jDE_12 did not. For PSO, none of the variations (PSO_6, PSO_12, PSO_30) exhibited a significant difference compared to the core PSO. In the case of MRFO, the variations were significantly different from the core MRFO, with MRFO_6 and MRFO_12 outperforming all the ABC variations. For ABC, no significant differences were observed among its variations, possibly due to its inherent limit parameter that restarts the search. For CRO, CRO_6 was significantly better than the core CRO (Table 1).

Regarding the parameter, the results from Table 1 do not indicate a universally optimal value across all the algorithms. For instance, jDE, PSO, and ABC performed best with set to 10% of , whereas MRFO and CRO achieved the best results with 2% of (Table 1). The varying impact of the strategy across the algorithms was expected, as each handles exploration and exploitation differently to avoid stagnation.

Further insights were gained by analyzing each algorithm’s wins, draws, and losses in pairwise comparisons. Since wins are more relevant for lower-performing algorithms, losses are crucial for top-performing ones, and draws provide less information, we focused on a detailed analysis of losses. Tables containing the results for wins and draws are provided in the Appendix A (Table A1 and Table A2).

Across 870 games, all the MAs lost at least some matches against every opponent (the first row in Table 2), except against the control RS algorithm (the last column in Table 2). A key observation is that the strategy improved jDE’s performance against ABC (highlighted in blue); however, ABC_30 still found the best solution overall in 16 games. Additionally, most of jDE’s losses came from its improved variations; for example, jDE lost to jDE_30 a total of 760 times (Table 2). Interestingly, when comparing the jDE row with its top-performing variations (jDE_30, jDE_6, jDE_12), jDE often had fewer losses than its superior counterparts in most columns. In this case, partitioning the optimization process did not outperform full runs. This aligns with findings suggesting that extended search durations can help overcome stagnation and yield better solutions, indicating that longer runs may be advantageous when computational resources are less constrained [41].

Table 2.

The Loss Outcomes for MS vs. MsMA on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

To explore performance on individual problems, we investigated whether specific problems exist where the strategy is particularly effective. Table 3 and Table 4 present the losses of each MA on problems F01 to F29.

Table 3.

The Loss Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table 4.

The Loss Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

Problems F03 and F04 were the most challenging for the overall best-performing jDE and its variations (Figure A1 and Figure A2). The greatest improvement from for jDE occurred on problem F05, where the losses decreased from 106 to 6 for jDE_12 and to 0 for jDE_6 and jDE_30 (Table 3).

Regarding ABC’s success against certain jDE runs (Table 2), Table 3 shows that ABC performed best on F05 with no losses (Figure A3), but it was the worst on F10, except for RS. Interestingly, the strategy worsened MRFO’s performance slightly on problem F03 (highlighted in blue in Table 3). Compared to MRFO, CRO, and ABC, PSO had the fewest losses on problem F21 (Table 4). Tables with wins and draws for individual problems are provided in the Appendix A (Table A3 and Table A5).

4.4. LTMA(MsMA): Performance Experiment

To determine whether complements and enhances performance, we conducted a similar experiment using the CEC’24 benchmark, following the same procedure as for in Section 4.3. Here, was applied to all variations, and for comparison, we included the best-performing variations of each MA from the previous experiment. Variations incorporating the strategy are labeled with the suffix _LTMA, along with the corresponding number label.

The experimental results are presented in a Leaderboard Table, displaying the ratings of MAs and their variations on the CEC’24 benchmark over 30 tournaments. For each MA, we report its rank based on overall rating, the rating deviation interval, the number of statistically significant positive (S+), and negative () differences at the 95% confidence level (Table 5).

Table 5.

The LTMA(MsMA) Leaderboard on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

Applying the LTMA strategy to all MsMA variants yielded performance improvements across most MA variants, except for jDE_30, the top performer from the prior experiment (Table 1 and Table 5). The minor rating difference between jDE_30 and jDE_LTMA_30 is statistically insignificant, and may stem from the stochastic nature of the MAs. Alternatively, LTMA may be less effective when an MA reaches the global optima consistently, as additional evaluations from duplicates fail to enhance solutions. Another possibility is the link between duplicate evaluations and stagnation, where mitigating one issue partially alleviates the other.

For PSO, there was no significant difference between PSO and its -enhanced variations (PSO_LTMA_6, PSO_LTMA_12, PSO_LTMA_30). The most substantial improvement was observed in CRO with , where the rating increased from 1370.09 to 1420.87, surpassing all MRFO and ABC variations (Table 5). As expected, self-adaptive MAs like jDE and ABC showed limited gains with , as they rarely enter stagnation cycles. The experiment also revealed a possible negative impact of on ABC, where ABC_LTMA_6 performed worse than the base ABC (Table 5), similar to ABC_6’s near-identical rating to the core ABC in the previous experiment (Table 1). This may be due to ’s precision, set to nine decimal places in the search space, where small changes could lead to larger fitness variations, resulting in more draws and fewer wins (draws were determined with a threshold of ).

Further understanding was gained by analyzing the losses in MA vs. MA comparisons, which provide detailed insights into relative performance. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The LTMA(MsMA) Loss Outcomes for MS vs. MsMA for the CEC’24 Benchmark.

The data from Table 6 reveal that jDE_LTMA_30 lost to jDE_30; however, jDE_LTMA_30 had fewer losses against jDE_30 (349) than jDE_30 had against jDE_LTMA_30 (404, highlighted in red in Table 6). The most significant rating differences for jDE_LTMA_30 stemmed from losses against jDE_LTMA_6 and jDE_LTMA_12 (highlighted in blue in Table 6). This suggests that utilized better solutions on average but with less precision, leading to more losses against higher-precision solutions. For deeper analysis, the results for wins and draws are provided in the Appendix A (Table A7 and Table A8).

To gain additional insights into performance on individual problems, we present the losses of each MA for specific problems in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

The Loss Outcomes of MAs with LTMA on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table 8.

The Loss Outcomes of MAs with LTMA on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

The results from Table 7 show that jDE_LTMA_6 would be the clear winner if problem F04 were excluded, where it performed poorly with 524 losses. Notably, RS achieved 75 wins on F02, corresponding to 675 losses (Table 7 and Table A9), and ABC and its variations remained unbeaten on F05 (Figure A3).

Analysis of the top five MAs showed consistent performance across problems F16 to F29 (Table 8). In contrast, the bottom-performing MAs like ABC, MRFO_LTMA_6, and ABC_LTMA_6 exhibited relatively large deviations despite fewer losses relative to their overall rank (Table 8). Additional Tables for wins and draws on individual problems are provided in the Appendix A (Table A9, Table A10, Table A11 and Table A12).

For a comparison involving more recent MAs, see Appendix A.4.

4.5. Experiment: Real-World Optimization Problem

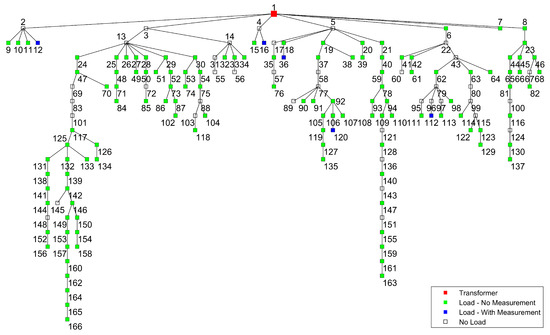

The selected real-world problem addresses the optimization of load flow analysis (LFA) in unbalanced power distribution networks with incomplete data. The example showed on Figure 4 illustrates a typical residential power distribution network with multiple consumers, each connected to three-phase supply lines. The network is characterized by its unbalanced nature, where the power consumption of each consumer may vary across the three phases. Where blue nodes represent consumers with partial measurements, green nodes represent consumers without measurements, and red is the transformer with complete measurement [74].

Figure 4.

Power Distribution Network Topology.

Due to limitations in the measurement infrastructure, comprehensive per-phase power consumption data for all consumers is often unavailable, resulting in sparse datasets. The optimization problem focuses on estimating the unmeasured per-phase active and reactive power consumption for consumers, given partial measurements of per-phase voltages and power.

The objective of the proposed optimization algorithm is to minimize the discrepancy between the calculated and measured per-phase voltages at a subset of monitored nodes (n). Specifically, the algorithm estimates: (1) per-phase active () and reactive power () for unmeasured consumers (), and (2) the distribution of measured () three-phase active power across individual phases for consumers with partial measurements (). The optimization does not constrain the solution to match measured aggregate power values at the network’s supply point, allowing for the estimation of network losses. The LFA approach used in the paper was Backward Forward Sweep (BFS) [75].

Network losses, which may account for up to 5% of power in larger systems, are assumed negligible in this problem to simplify the optimization model by excluding the loss parameters. The optimization was subject to the following constraints:

- 1.

- Maximum three-phase active power consumption per consumer (), reflecting realistic load limits (Equation (11)).

- 2.

- Maximum per-phase current, constrained by fuse () ratings to ensure safe operation (Equation (12)).

- 3.

- 4.

- Inductive-only reactive power consumption, preventing unintended reactive power exchange between consumers.

The optimization goal is to minimize the difference () between the calculated () and measured () per-phase voltages at monitored nodes, skipping the first node-transformer (Equation (15)). The BFS algorithm computes the voltage at each node based on the estimated power consumption.

Based on the optimization goal and constraints, the fitness function is defined by Equation (16).

These constraints ensure that the estimated power consumption remains physically plausible and adheres to the operational limits of the distribution network. The problem is formulated to handle the stochastic and nonlinear nature of load flow analysis, leveraging sparse data to achieve accurate voltage estimation.

The experimental setup and statistical analysis follow the configuration detailed in Section 4.1. For the LFA problem, the maximum number of function evaluations was set to . To show the concept and limit the number of parameters we have limited ourselves to the “leftmost” feeder with five nodes beside the transformer (Figure 4): one transformer node where all the data are known, one measured node with known per-phase voltages U and total P, and three unmeasured nodes. For the unmeasured nodes, the optimization estimates per-phase P and Q. Additionally, for the measured node, the total three-phase active power is distributed across the three phases.

In total, the optimization involves 24 parameters: 9 parameters for the unmeasured nodes (3 nodes × 3 phases for P), 12 parameters for reactive power (4 nodes × 3 phases for Q), and 3 parameters for the per-phase distribution of active power at the measured node.

The performance of various metaheuristic algorithms on the LFA problem is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

The MAs Leaderboard on The LFA Problem.

The results demonstrate that the MRFO algorithm, enhanced with LTMA and MsMA strategies, outperformed the other algorithms significantly, achieving the highest rating value of 1843, which is significantly better than the 32 other algorithms variations. The jDE algorithm, also enhanced with LTMA and MsMA strategies, ranks second with a rating value of 1770.45, outperforming the 23 other algorithms significantly. Furthermore, all the tested LTMA configurations combined with MsMA surpassed the performance of their respective baseline algorithms (marked with the red color in Table 5). Notably, MRFO and CRO, despite being among the lowest-performing algorithms on the CEC’24 benchmark (Table 5), achieved top or near-top performances with these strategies.

For a comparison involving more recent MAs, see Appendix A.4.

5. Discussion

The stagnation problem is as old as MAs themselves. It is well recognized that stagnation occurs in MAs frequently, often when the algorithm struggles to transition from the exploitation phase back to effective exploration. Researchers have tackled this issue through various strategies, among which self-adaptive algorithms have demonstrated notable success. Self-adaptation can be applied to different aspects of MAs, ranging from adjusting the internal parameters dynamically (e.g., mutation rates or learning factors), to introducing individual-level control, or modifying the population size based on stagnation detection [48,76]. Another common practice is to use stagnation as a stopping criterion. This approach serves a dual purpose: it prevents the waste of computational resources when progress stalls, while also avoiding premature termination when other criteria (e.g., or iteration limits) might otherwise halt optimization too early [29].

In this study, we proposed a meta-level strategy, , that partitions the search process based on stagnation detection. A key advantage of meta-level strategies like is their generality: they can be applied across different core MAs without requiring modifications to the underlying algorithm. This facilitates fairer comparisons and reusable optimization logic across MA variants, eliminating the need to define and publish a new variant for every core MA. For instance, one might claim to have developed five novel MAs when, in reality, only a self-adaptive stagnation mechanism has been applied to the existing core MAs. Such an approach offers little benefit to the community, as it obscures the new MA’s behavior and its performance relative to the established methods. Additionally, because meta-strategies operate by wrapping core algorithms, they can be nested or chained with other meta-level mechanisms. This was demonstrated through the integration of with , illustrating how different meta-strategies can synergize to enhance performance and convergence.

However, not all strategies are suitable for meta-level abstraction. Generally, strategies with broader generalization capabilities are better suited for meta-level applications. A balance must be struck between what can be externalized at the meta-level and what must remain embedded within the core algorithm. For example, global parameters such as (utilized by ) and solution evaluation control (leveraged by ) are well suited for meta-level adaptation. In contrast, tightly coupled internal components—such as parent selection or recombination operators for generating new solution candidates—are challenging to expose or modify externally due to their interdependencies at each optimization step.

During the experimentation and development, we encountered several practical challenges. Notably, the proposed method employs a reset mechanism based on a stopping condition termed , which partitions into unequal partitions depending on the algorithm’s performance. Consequently, the final partition,, can sometimes be extremely small—occasionally even smaller than the population size. This can cause errors in algorithms that require a minimum number of evaluations to function correctly. To address this, we propose that the algorithms implement a method, which returns the minimum number of evaluations needed for safe operation. If the remaining evaluation budget falls below this threshold, the algorithm can skip execution, avoiding runtime errors. To utilize otherwise unused evaluations effectively, we applied a fallback random search strategy, ensuring that even small remaining budgets contribute to the optimization process.

6. Conclusions

This study tackled the persistent challenge of stagnation in MAs by introducing a general meta-level strategy, , designed to enhance optimization performance. The proposed strategy improved performance across all tested MAs on the 29 CEC’24 benchmark problems, boosting the rankings of jDE, MRFO, and CRO significantly. Notably, applying altered the relative rankings of some algorithms; for instance, MRFO surpassed ABC in overall performance (Table 1).

Beyond its general applicability, the study demonstrated the feasibility of nesting meta-strategies through the integration of with , highlighting their synergistic potential. Leveraging enhanced the performance of most variations further, with CRO showing the greatest improvement—specifically, CRO_LTMA_12 overtook MRFO_LTMA_6 in the rankings (Table 5).

For the LFA optimization problem, the experimental results demonstrate that nearly all algorithms enhanced with MsMA and LTMA strategies outperformed their baseline counterparts significantly, with the exception of the ABC algorithm. Notably, the MRFO algorithm, despite being among the lowest-performing algorithms on the CEC’24 benchmark (Table 5), achieved the highest performance on the LFA problem, with a rating value of 1843 (Table 9). This suggests that MRFO’s search mechanisms or parameter configurations are particularly well-suited to the characteristics of the LFA problem, highlighting its potential for real-world power distribution optimization.

Future work should focus on developing more advanced meta-strategies tailored to the specific characteristics of both the core algorithm and the problem domain. Additionally, the framework could be extended to other optimization contexts, such as multi-objective, dynamic, and constrained optimization.

This study encourages further research into meta-level strategies and their integration, opening new avenues for a better understanding of the general strategies and characteristics of modern MAs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Č., M.M. (Marjan Mernik) and M.R.; investigation, M.Č., M.M. (Marjan Mernik) and M.R.; methodology, M.Č.; software, M.Č., M.B., M.P., M.M. (Matej Moravec) and M.R.; validation, M.Č., M.M. (Marjan Mernik), M.P., M.B., M.M. (Matej Moravec) and M.R.; writing, original draft, M.Č., M.M. (Marjan Mernik), M.B. and M.R.; writing, review and editing, M.Č., M.M. (Marjan Mernik), M.P., M.B., M.M. (Matej Moravec) and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency Grant Number P2-0041 (B), P2-0114, and P2-0115.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://github.com/UM-LPM/EARS, accessed on 22 May 2025.

Acknowledgments

AI-assisted tools have been used to improve the English language.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Experiment Results

Appendix A.1. Selected CEC’24 Benchmark Problems

This subsection presents the CEC’24 benchmark problems selected for the experiments. The accompanying Figures depict these benchmark functions in their original form, without applying rotation (rotation matrix M) or shifting (shift vector o). For enhanced visualization, the functions are illustrated in two dimensions, although they are defined in n dimensions, where n represents the problem’s dimensionality. For further details on the CEC’24 benchmark suite, refer to the competition documentation [71,72].

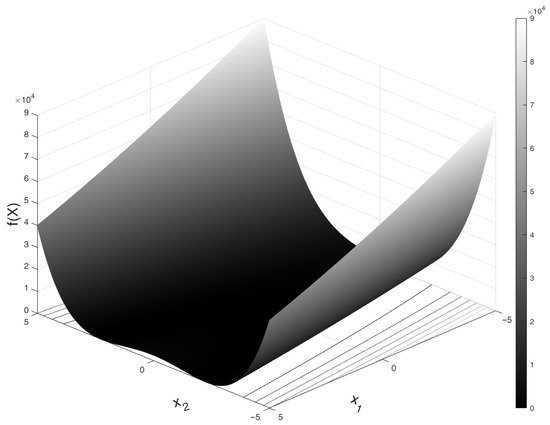

Figure A1.

F03: Rosenbrock’s Function.

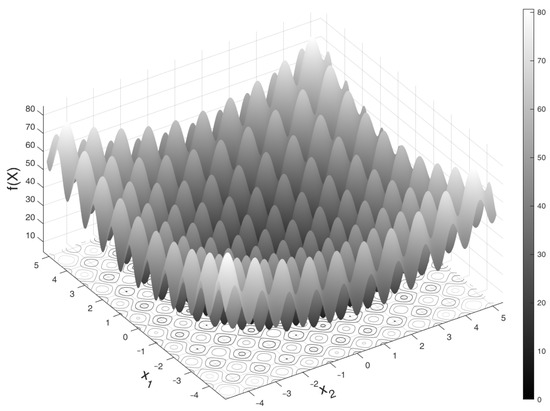

Figure A2.

F04: Rastrigin’s Function (not rotated or shifted).

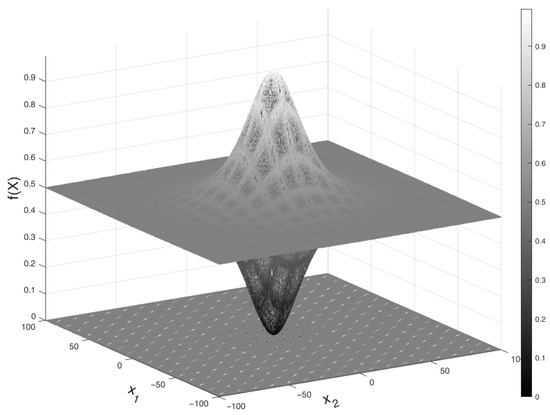

Figure A3.

F05: Schaffer’s Function.

Appendix A.2. The MsMA Experiment

The following Tables present the results of the experiment on the CEC’24 benchmark. They report the number of wins and draws for each algorithm, based on pairwise comparisons and their performance on individual benchmark problems from F01 to F29. Additional Tables showing the number of losses are provided in Appendix A.

Table A1.

MsMA Draw Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

Table A1.

MsMA Draw Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

| jDE_30 | jDE_6 | jDE_12 | jDE | PSO_30 | PSO_6 | PSO_12 | PSO | MRFO_6 | MRFO_12 | ABC_30 | ABC_12 | ABC_6 | ABC | MRFO_30 | CRO_6 | CRO_12 | MRFO | CRO_30 | CRO | RS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 0 | 698 | 188 | 81 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE_6 | 698 | 0 | 192 | 83 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE_12 | 188 | 192 | 0 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE | 81 | 83 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 24 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 30 | 32 | 26 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 25 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 32 | 30 | 0 | 24 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_30 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_12 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_6 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC | 29 | 30 | 29 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_30 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A2.

MsMA Win Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

Table A2.

MsMA Win Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

| jDE_30 | jDE_6 | jDE_12 | jDE | PSO_30 | PSO_6 | PSO_12 | PSO | MRFO_6 | MRFO_12 | ABC_30 | ABC_12 | ABC_6 | ABC | MRFO_30 | CRO_6 | CRO_12 | MRFO | CRO_30 | CRO | RS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 0 | 138 | 639 | 760 | 867 | 866 | 867 | 867 | 863 | 866 | 825 | 828 | 825 | 827 | 863 | 867 | 868 | 865 | 868 | 869 | 870 |

| jDE_6 | 34 | 0 | 613 | 747 | 847 | 848 | 846 | 848 | 857 | 856 | 823 | 823 | 821 | 824 | 859 | 853 | 858 | 855 | 860 | 858 | 870 |

| jDE_12 | 43 | 65 | 0 | 729 | 861 | 862 | 865 | 867 | 859 | 864 | 823 | 824 | 822 | 826 | 860 | 864 | 868 | 859 | 866 | 868 | 870 |

| jDE | 29 | 40 | 35 | 0 | 863 | 864 | 865 | 864 | 864 | 865 | 824 | 825 | 824 | 825 | 862 | 869 | 868 | 865 | 869 | 869 | 870 |

| PSO_30 | 3 | 23 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 426 | 421 | 420 | 550 | 569 | 533 | 532 | 533 | 532 | 583 | 611 | 633 | 642 | 668 | 672 | 870 |

| PSO_6 | 3 | 21 | 8 | 6 | 415 | 0 | 403 | 419 | 554 | 563 | 525 | 511 | 527 | 534 | 602 | 596 | 626 | 635 | 670 | 694 | 868 |

| PSO_12 | 3 | 24 | 5 | 5 | 420 | 437 | 0 | 443 | 549 | 561 | 524 | 514 | 513 | 533 | 597 | 583 | 618 | 629 | 677 | 674 | 870 |

| PSO | 3 | 22 | 3 | 6 | 421 | 419 | 397 | 0 | 559 | 553 | 522 | 517 | 513 | 524 | 581 | 601 | 616 | 622 | 655 | 674 | 870 |

| MRFO_6 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 296 | 290 | 296 | 287 | 0 | 436 | 481 | 477 | 486 | 494 | 477 | 477 | 502 | 540 | 544 | 589 | 869 |

| MRFO_12 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 281 | 287 | 288 | 297 | 410 | 0 | 477 | 466 | 464 | 471 | 454 | 452 | 481 | 513 | 545 | 550 | 868 |

| ABC_30 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 31 | 337 | 345 | 346 | 348 | 389 | 393 | 0 | 446 | 437 | 426 | 438 | 434 | 480 | 484 | 517 | 533 | 855 |

| ABC_12 | 13 | 17 | 17 | 30 | 338 | 359 | 356 | 353 | 393 | 404 | 394 | 0 | 423 | 400 | 434 | 436 | 476 | 493 | 526 | 550 | 857 |

| ABC_6 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 31 | 337 | 343 | 357 | 357 | 384 | 406 | 403 | 417 | 0 | 412 | 434 | 456 | 471 | 476 | 513 | 545 | 856 |

| ABC | 14 | 16 | 15 | 30 | 338 | 336 | 337 | 346 | 376 | 399 | 414 | 440 | 428 | 0 | 440 | 437 | 468 | 490 | 511 | 549 | 848 |

| MRFO_30 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 268 | 248 | 255 | 271 | 372 | 399 | 432 | 436 | 436 | 430 | 0 | 440 | 460 | 506 | 528 | 549 | 869 |

| CRO_6 | 3 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 259 | 274 | 287 | 269 | 393 | 418 | 436 | 434 | 414 | 433 | 430 | 0 | 457 | 512 | 522 | 511 | 868 |

| CRO_12 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 237 | 244 | 252 | 254 | 368 | 389 | 390 | 394 | 399 | 402 | 410 | 413 | 0 | 475 | 478 | 516 | 863 |

| MRFO | 4 | 14 | 9 | 3 | 217 | 224 | 230 | 237 | 314 | 347 | 386 | 377 | 394 | 380 | 357 | 358 | 395 | 0 | 454 | 463 | 869 |

| CRO_30 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 202 | 200 | 193 | 215 | 326 | 325 | 353 | 344 | 357 | 359 | 342 | 348 | 392 | 416 | 0 | 451 | 862 |

| CRO | 1 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 198 | 176 | 196 | 196 | 281 | 320 | 337 | 320 | 325 | 321 | 321 | 359 | 354 | 407 | 419 | 0 | 856 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 14 | 0 |

Table A3.

The Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table A3.

The Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

| F01 | F02 | F03 | F04 | F05 | F06 | F07 | F08 | F09 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 510 | 510 | 460 | 567 | 405 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 |

| jDE_6 | 510 | 510 | 437 | 352 | 407 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 |

| jDE_12 | 510 | 510 | 424 | 531 | 406 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 |

| jDE | 510 | 510 | 448 | 561 | 390 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 |

| PSO_30 | 294 | 267 | 256 | 406 | 237 | 295 | 378 | 404 | 248 | 408 | 372 | 359 | 370 | 388 | 318 |

| PSO_6 | 276 | 146 | 228 | 373 | 165 | 247 | 363 | 404 | 263 | 412 | 374 | 391 | 396 | 426 | 356 |

| PSO_12 | 273 | 179 | 228 | 410 | 207 | 253 | 397 | 428 | 272 | 406 | 358 | 392 | 387 | 362 | 291 |

| PSO | 284 | 325 | 211 | 385 | 207 | 274 | 361 | 403 | 260 | 408 | 358 | 381 | 384 | 386 | 298 |

| MRFO_6 | 330 | 224 | 290 | 236 | 83 | 211 | 289 | 262 | 119 | 311 | 362 | 275 | 355 | 266 | 261 |

| MRFO_12 | 304 | 311 | 254 | 268 | 80 | 197 | 295 | 220 | 135 | 292 | 388 | 277 | 349 | 274 | 275 |

| ABC_30 | 366 | 75 | 464 | 132 | 407 | 295 | 119 | 82 | 377 | 80 | 157 | 136 | 146 | 165 | 287 |

| ABC_12 | 363 | 65 | 439 | 182 | 407 | 293 | 109 | 67 | 369 | 88 | 136 | 102 | 151 | 136 | 302 |

| ABC_6 | 359 | 77 | 468 | 137 | 407 | 287 | 115 | 96 | 374 | 91 | 162 | 78 | 160 | 104 | 332 |

| ABC | 381 | 39 | 433 | 125 | 407 | 300 | 133 | 103 | 363 | 60 | 165 | 167 | 130 | 172 | 313 |

| MRFO_30 | 220 | 462 | 335 | 196 | 72 | 241 | 267 | 266 | 69 | 261 | 398 | 169 | 356 | 188 | 226 |

| CRO_6 | 112 | 267 | 181 | 366 | 263 | 323 | 304 | 315 | 345 | 245 | 117 | 325 | 141 | 323 | 202 |

| CRO_12 | 112 | 346 | 150 | 294 | 298 | 308 | 261 | 288 | 254 | 247 | 131 | 316 | 131 | 299 | 179 |

| MRFO | 141 | 464 | 308 | 200 | 68 | 153 | 230 | 233 | 125 | 270 | 387 | 165 | 379 | 160 | 168 |

| CRO_30 | 124 | 384 | 112 | 293 | 332 | 206 | 244 | 269 | 261 | 258 | 106 | 296 | 116 | 243 | 129 |

| CRO | 141 | 391 | 91 | 286 | 328 | 197 | 215 | 240 | 246 | 243 | 109 | 251 | 98 | 188 | 143 |

| RS | 0 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

Table A4.

The Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

Table A4.

The Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

| F16 | F17 | F18 | F19 | F20 | F21 | F22 | F23 | F24 | F25 | F26 | F27 | F28 | F29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 | 569 |

| jDE_6 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 | 566 |

| jDE_12 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 |

| jDE | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 510 |

| PSO_30 | 321 | 398 | 331 | 231 | 269 | 315 | 300 | 300 | 287 | 308 | 271 | 240 | 276 | 390 |

| PSO_6 | 308 | 390 | 406 | 258 | 297 | 318 | 314 | 299 | 272 | 282 | 312 | 222 | 303 | 379 |

| PSO_12 | 331 | 377 | 374 | 276 | 301 | 318 | 291 | 289 | 272 | 307 | 292 | 270 | 257 | 381 |

| PSO | 290 | 396 | 362 | 245 | 275 | 318 | 327 | 280 | 260 | 284 | 236 | 247 | 264 | 369 |

| MRFO_6 | 210 | 244 | 329 | 289 | 273 | 264 | 215 | 229 | 331 | 224 | 230 | 343 | 163 | 353 |

| MRFO_12 | 217 | 226 | 304 | 286 | 206 | 230 | 165 | 259 | 370 | 215 | 175 | 284 | 184 | 283 |

| ABC_30 | 322 | 220 | 100 | 313 | 339 | 132 | 358 | 260 | 347 | 389 | 390 | 338 | 375 | 119 |

| ABC_12 | 330 | 186 | 120 | 314 | 363 | 137 | 384 | 339 | 332 | 393 | 389 | 340 | 355 | 78 |

| ABC_6 | 317 | 212 | 71 | 337 | 322 | 147 | 317 | 404 | 329 | 405 | 401 | 321 | 361 | 61 |

| ABC | 311 | 201 | 119 | 329 | 322 | 138 | 298 | 275 | 358 | 370 | 410 | 366 | 359 | 85 |

| MRFO_30 | 187 | 271 | 322 | 217 | 220 | 223 | 152 | 197 | 292 | 231 | 156 | 270 | 173 | 288 |

| CRO_6 | 237 | 197 | 298 | 284 | 216 | 232 | 237 | 248 | 128 | 178 | 195 | 108 | 286 | 271 |

| CRO_12 | 254 | 190 | 304 | 222 | 172 | 201 | 205 | 233 | 150 | 164 | 176 | 133 | 203 | 281 |

| MRFO | 171 | 276 | 206 | 238 | 180 | 193 | 106 | 137 | 157 | 100 | 104 | 285 | 157 | 271 |

| CRO_30 | 140 | 134 | 199 | 138 | 174 | 198 | 213 | 177 | 85 | 103 | 187 | 167 | 202 | 212 |

| CRO | 134 | 160 | 235 | 96 | 151 | 181 | 198 | 154 | 110 | 119 | 156 | 120 | 162 | 259 |

| RS | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A5.

The Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table A5.

The Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

| F01 | F02 | F03 | F04 | F05 | F06 | F07 | F08 | F09 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 90 | 90 | 27 | 0 | 189 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| jDE_6 | 90 | 90 | 33 | 0 | 193 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| jDE_12 | 90 | 90 | 27 | 0 | 188 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| jDE | 90 | 90 | 28 | 0 | 106 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PSO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_6 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_12 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_30 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A6.

The Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

Table A6.

The Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F16–F29).

| F16 | F17 | F18 | F19 | F20 | F21 | F22 | F23 | F24 | F25 | F26 | F27 | F28 | F29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| jDE_6 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| jDE_12 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| jDE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PSO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 159 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 162 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 136 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 105 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Appendix A.3. The LTMA(MsMA) Experiment

The following Tables present the results of the experiment on the CEC’24 benchmark. They report the number of wins and draws for each algorithm based on pairwise comparisons, as well as their performance on individual benchmark problems from F01 to F29. Additional Tables showing the number of losses are provided in Appendix A.

Table A7.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

Table A7.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

| jDE_30 | jDE_LTMA_30 | jDE_LTMA_6 | jDE_LTMA_12 | jDE | PSO_LTMA_6 | PSO_LTMA_12 | PSO_LTMA_30 | PSO_30 | PSO | CRO_LTMA_12 | MRFO_LTMA_6 | CRO_LTMA_6 | MRFO_6 | ABC_LTMA_12 | ABC_LTMA_30 | MRFO_LTMA_30 | ABC_30 | ABC | MRFO_LTMA_12 | ABC_LTMA_6 | CRO_LTMA_30 | CRO_6 | MRFO | CRO | RS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 0 | 349 | 55 | 402 | 760 | 867 | 867 | 865 | 867 | 867 | 866 | 864 | 867 | 863 | 825 | 828 | 863 | 825 | 827 | 861 | 827 | 868 | 867 | 865 | 869 | 870 |

| jDE_LTMA_30 | 404 | 0 | 434 | 422 | 750 | 863 | 866 | 860 | 863 | 863 | 863 | 862 | 862 | 863 | 822 | 825 | 863 | 822 | 823 | 860 | 825 | 865 | 864 | 861 | 867 | 870 |

| jDE_LTMA_6 | 36 | 348 | 0 | 372 | 746 | 838 | 840 | 841 | 841 | 842 | 840 | 841 | 840 | 846 | 816 | 818 | 846 | 814 | 823 | 844 | 815 | 841 | 841 | 850 | 849 | 870 |

| jDE_LTMA_12 | 39 | 354 | 74 | 0 | 747 | 851 | 853 | 853 | 851 | 854 | 851 | 855 | 850 | 858 | 822 | 825 | 859 | 822 | 823 | 859 | 823 | 858 | 857 | 859 | 860 | 870 |

| jDE | 29 | 36 | 51 | 39 | 0 | 865 | 868 | 864 | 863 | 864 | 866 | 864 | 867 | 864 | 825 | 825 | 862 | 824 | 825 | 862 | 825 | 869 | 869 | 865 | 869 | 870 |

| PSO_LTMA_6 | 3 | 7 | 32 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 442 | 462 | 455 | 485 | 600 | 598 | 607 | 598 | 583 | 576 | 624 | 575 | 574 | 603 | 581 | 635 | 650 | 653 | 721 | 869 |

| PSO_LTMA_12 | 3 | 4 | 30 | 17 | 1 | 397 | 0 | 437 | 447 | 472 | 575 | 563 | 605 | 585 | 550 | 562 | 592 | 559 | 555 | 597 | 565 | 620 | 636 | 653 | 710 | 869 |

| PSO_LTMA_30 | 5 | 9 | 29 | 17 | 6 | 378 | 403 | 0 | 410 | 420 | 574 | 558 | 578 | 554 | 529 | 528 | 560 | 539 | 538 | 574 | 544 | 595 | 611 | 630 | 679 | 870 |

| PSO_30 | 3 | 7 | 29 | 19 | 7 | 386 | 394 | 430 | 0 | 420 | 567 | 551 | 574 | 550 | 518 | 540 | 563 | 533 | 532 | 556 | 545 | 590 | 611 | 642 | 672 | 870 |

| PSO | 3 | 7 | 28 | 16 | 6 | 355 | 368 | 418 | 421 | 0 | 572 | 560 | 551 | 559 | 519 | 520 | 557 | 522 | 524 | 578 | 540 | 590 | 601 | 622 | 674 | 870 |

| CRO_LTMA_12 | 4 | 7 | 30 | 19 | 4 | 270 | 295 | 296 | 303 | 298 | 0 | 423 | 501 | 460 | 468 | 484 | 488 | 491 | 488 | 466 | 476 | 473 | 481 | 538 | 584 | 870 |

| MRFO_LTMA_6 | 5 | 7 | 27 | 13 | 5 | 246 | 280 | 286 | 293 | 283 | 447 | 0 | 438 | 422 | 506 | 501 | 447 | 489 | 514 | 433 | 503 | 471 | 493 | 536 | 570 | 870 |

| CRO_LTMA_6 | 3 | 8 | 30 | 20 | 3 | 263 | 265 | 292 | 296 | 319 | 369 | 432 | 0 | 445 | 496 | 502 | 479 | 509 | 505 | 465 | 500 | 454 | 463 | 534 | 580 | 868 |

| MRFO_6 | 4 | 5 | 22 | 9 | 6 | 248 | 260 | 291 | 296 | 287 | 410 | 415 | 425 | 0 | 477 | 486 | 452 | 481 | 494 | 436 | 480 | 471 | 477 | 540 | 589 | 869 |

| ABC_LTMA_12 | 16 | 19 | 24 | 18 | 30 | 287 | 320 | 341 | 352 | 351 | 402 | 364 | 374 | 393 | 0 | 408 | 394 | 418 | 399 | 414 | 454 | 461 | 454 | 478 | 560 | 853 |

| ABC_LTMA_30 | 13 | 16 | 22 | 15 | 30 | 294 | 308 | 342 | 330 | 350 | 386 | 369 | 368 | 384 | 432 | 0 | 407 | 430 | 427 | 412 | 467 | 457 | 435 | 487 | 544 | 853 |

| MRFO_LTMA_30 | 4 | 5 | 22 | 8 | 3 | 227 | 259 | 290 | 288 | 294 | 382 | 397 | 391 | 393 | 476 | 463 | 0 | 476 | 469 | 419 | 482 | 448 | 456 | 504 | 550 | 868 |

| ABC_30 | 16 | 19 | 26 | 18 | 31 | 295 | 311 | 331 | 337 | 348 | 379 | 381 | 361 | 389 | 422 | 410 | 394 | 0 | 426 | 413 | 460 | 457 | 434 | 484 | 533 | 855 |

| ABC | 14 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 30 | 296 | 315 | 332 | 338 | 346 | 382 | 356 | 365 | 376 | 441 | 413 | 401 | 414 | 0 | 413 | 465 | 452 | 437 | 490 | 549 | 848 |

| MRFO_LTMA_12 | 5 | 5 | 22 | 8 | 5 | 243 | 249 | 273 | 292 | 269 | 404 | 411 | 405 | 407 | 456 | 458 | 434 | 457 | 457 | 0 | 460 | 440 | 454 | 505 | 545 | 870 |

| ABC_LTMA_6 | 14 | 16 | 25 | 17 | 30 | 289 | 305 | 326 | 325 | 330 | 394 | 367 | 370 | 390 | 386 | 373 | 388 | 380 | 375 | 410 | 0 | 449 | 434 | 468 | 528 | 859 |

| CRO_LTMA_30 | 2 | 5 | 29 | 12 | 1 | 235 | 250 | 275 | 280 | 280 | 397 | 399 | 416 | 399 | 409 | 413 | 422 | 413 | 418 | 430 | 421 | 0 | 452 | 501 | 547 | 863 |

| CRO_6 | 3 | 6 | 29 | 13 | 1 | 220 | 234 | 259 | 259 | 269 | 389 | 377 | 407 | 393 | 416 | 435 | 414 | 436 | 433 | 416 | 436 | 418 | 0 | 512 | 511 | 868 |

| MRFO | 4 | 5 | 19 | 10 | 3 | 206 | 206 | 228 | 217 | 237 | 332 | 317 | 336 | 314 | 392 | 383 | 355 | 386 | 380 | 353 | 402 | 369 | 358 | 0 | 463 | 869 |

| CRO | 1 | 3 | 21 | 10 | 1 | 149 | 160 | 191 | 198 | 196 | 286 | 300 | 290 | 281 | 310 | 326 | 320 | 337 | 321 | 325 | 342 | 323 | 359 | 407 | 0 | 856 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 17 | 2 | 15 | 22 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 0 |

Table A8.

LTMA(MsMA) Draw Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

Table A8.

LTMA(MsMA) Draw Outcomes in MA vs. MA Comparisons on the CEC’24 Benchmark.

| jDE_30 | jDE_LTMA_30 | jDE_LTMA_6 | jDE_LTMA_12 | jDE | PSO_LTMA_6 | PSO_LTMA_12 | PSO_LTMA_30 | PSO_30 | PSO | CRO_LTMA_12 | MRFO_LTMA_6 | CRO_LTMA_6 | MRFO_6 | ABC_LTMA_12 | ABC_LTMA_30 | MRFO_LTMA_30 | ABC_30 | ABC | MRFO_LTMA_12 | ABC_LTMA_6 | CRO_LTMA_30 | CRO_6 | MRFO | CRO | RS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 0 | 117 | 779 | 429 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 29 | 29 | 3 | 29 | 29 | 4 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE_LTMA_30 | 117 | 0 | 88 | 94 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 29 | 2 | 29 | 29 | 5 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE_LTMA_6 | 779 | 88 | 0 | 424 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 2 | 30 | 30 | 4 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE_LTMA_12 | 429 | 94 | 424 | 0 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 30 | 30 | 3 | 30 | 30 | 3 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| jDE | 81 | 84 | 73 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15 | 5 | 15 | 15 | 3 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_LTMA_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_LTMA_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 0 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_LTMA_30 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 32 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| PSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 32 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_LTMA_12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_LTMA_6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_LTMA_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_LTMA_12 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_LTMA_30 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_LTMA_30 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_30 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC | 29 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO_LTMA_12 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| ABC_LTMA_6 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_LTMA_30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MRFO | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A9.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table A9.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

| F01 | F02 | F03 | F04 | F05 | F06 | F07 | F08 | F09 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 630 | 639 | 574 | 704 | 495 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 |

| jDE_LTMA_30 | 630 | 639 | 537 | 648 | 496 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 |

| jDE_LTMA_6 | 630 | 630 | 555 | 226 | 497 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| jDE_LTMA_12 | 630 | 639 | 535 | 502 | 497 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 |

| jDE | 630 | 639 | 553 | 707 | 481 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 |

| PSO_LTMA_6 | 377 | 194 | 278 | 534 | 216 | 292 | 473 | 476 | 309 | 509 | 408 | 529 | 479 | 526 | 485 |

| PSO_LTMA_12 | 381 | 225 | 300 | 474 | 278 | 312 | 433 | 527 | 303 | 514 | 433 | 474 | 466 | 508 | 442 |

| PSO_LTMA_30 | 337 | 342 | 313 | 492 | 301 | 298 | 404 | 509 | 314 | 504 | 474 | 458 | 476 | 466 | 386 |

| PSO_30 | 367 | 403 | 306 | 483 | 328 | 330 | 433 | 501 | 282 | 517 | 469 | 440 | 450 | 475 | 339 |

| PSO | 355 | 485 | 273 | 461 | 293 | 301 | 432 | 504 | 298 | 517 | 451 | 452 | 472 | 464 | 328 |

| CRO_LTMA_12 | 60 | 290 | 185 | 538 | 300 | 477 | 432 | 383 | 442 | 311 | 189 | 446 | 237 | 387 | 348 |

| MRFO_LTMA_6 | 358 | 340 | 367 | 340 | 80 | 313 | 311 | 284 | 114 | 374 | 466 | 299 | 434 | 350 | 353 |

| CRO_LTMA_6 | 30 | 200 | 126 | 559 | 228 | 415 | 494 | 411 | 512 | 264 | 203 | 342 | 292 | 346 | 431 |

| MRFO_6 | 399 | 339 | 355 | 272 | 98 | 236 | 345 | 303 | 137 | 390 | 456 | 308 | 427 | 310 | 295 |

| ABC_LTMA_12 | 423 | 87 | 561 | 175 | 497 | 334 | 117 | 79 | 417 | 117 | 191 | 103 | 195 | 158 | 324 |

| ABC_LTMA_30 | 464 | 64 | 527 | 182 | 497 | 332 | 144 | 106 | 461 | 111 | 172 | 151 | 144 | 189 | 349 |

| MRFO_LTMA_30 | 343 | 582 | 339 | 260 | 109 | 254 | 320 | 231 | 97 | 298 | 489 | 315 | 446 | 224 | 224 |

| ABC_30 | 443 | 98 | 591 | 153 | 497 | 327 | 120 | 104 | 429 | 93 | 167 | 145 | 164 | 172 | 313 |

| ABC | 453 | 57 | 559 | 135 | 497 | 345 | 139 | 128 | 432 | 78 | 183 | 184 | 149 | 184 | 346 |

| MRFO_LTMA_12 | 323 | 455 | 381 | 280 | 93 | 274 | 316 | 295 | 148 | 337 | 503 | 297 | 441 | 317 | 305 |

| ABC_LTMA_6 | 434 | 98 | 565 | 167 | 497 | 321 | 136 | 93 | 419 | 111 | 157 | 99 | 172 | 110 | 298 |

| CRO_LTMA_30 | 184 | 438 | 146 | 444 | 390 | 391 | 400 | 430 | 381 | 312 | 139 | 393 | 109 | 346 | 193 |

| CRO_6 | 158 | 407 | 206 | 438 | 363 | 377 | 342 | 377 | 401 | 312 | 139 | 378 | 152 | 374 | 200 |

| MRFO | 205 | 587 | 381 | 241 | 85 | 159 | 265 | 270 | 131 | 329 | 484 | 187 | 471 | 186 | 185 |

| CRO | 206 | 534 | 100 | 334 | 438 | 212 | 243 | 289 | 273 | 302 | 127 | 300 | 95 | 208 | 156 |

| RS | 0 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 |

Table A10.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F06–F29).

Table A10.

LTMA(MsMA) Win Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F06–F29).

| F16 | F17 | F18 | F19 | F20 | F21 | F22 | F23 | F24 | F25 | F26 | F27 | F28 | F29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 | 688 |

| jDE_LTMA_30 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 | 708 |

| jDE_LTMA_6 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| jDE_LTMA_12 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 |

| jDE | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 | 630 |

| PSO_LTMA_6 | 465 | 470 | 555 | 418 | 365 | 378 | 368 | 376 | 430 | 445 | 429 | 322 | 352 | 499 |

| PSO_LTMA_12 | 411 | 458 | 499 | 387 | 364 | 378 | 363 | 352 | 319 | 403 | 390 | 350 | 341 | 519 |

| PSO_LTMA_30 | 319 | 489 | 484 | 323 | 351 | 378 | 296 | 330 | 339 | 324 | 349 | 293 | 337 | 452 |

| PSO_30 | 389 | 492 | 395 | 252 | 306 | 374 | 335 | 330 | 354 | 342 | 312 | 315 | 313 | 477 |

| PSO | 333 | 483 | 447 | 259 | 319 | 378 | 375 | 303 | 322 | 318 | 270 | 321 | 304 | 463 |

| CRO_LTMA_12 | 368 | 299 | 367 | 328 | 320 | 253 | 371 | 356 | 163 | 239 | 267 | 137 | 361 | 363 |

| MRFO_LTMA_6 | 294 | 336 | 326 | 330 | 279 | 346 | 251 | 281 | 368 | 302 | 251 | 362 | 215 | 361 |

| CRO_LTMA_6 | 405 | 307 | 370 | 427 | 362 | 172 | 425 | 375 | 77 | 259 | 358 | 82 | 376 | 252 |

| MRFO_6 | 233 | 282 | 390 | 319 | 309 | 312 | 224 | 234 | 416 | 257 | 260 | 423 | 182 | 419 |

| ABC_LTMA_12 | 378 | 237 | 96 | 342 | 396 | 155 | 453 | 472 | 389 | 475 | 446 | 460 | 421 | 86 |

| ABC_LTMA_30 | 361 | 213 | 149 | 372 | 285 | 134 | 365 | 417 | 421 | 494 | 492 | 437 | 446 | 99 |

| MRFO_LTMA_30 | 216 | 343 | 350 | 316 | 269 | 276 | 218 | 229 | 461 | 273 | 190 | 382 | 188 | 332 |

| ABC_30 | 365 | 251 | 111 | 348 | 419 | 140 | 406 | 322 | 425 | 463 | 462 | 435 | 428 | 139 |

| ABC | 351 | 209 | 137 | 366 | 397 | 149 | 338 | 334 | 445 | 430 | 514 | 461 | 422 | 103 |

| MRFO_LTMA_12 | 179 | 305 | 330 | 243 | 278 | 314 | 188 | 221 | 353 | 227 | 173 | 353 | 238 | 367 |

| ABC_LTMA_6 | 385 | 229 | 76 | 365 | 433 | 168 | 440 | 515 | 355 | 457 | 400 | 241 | 431 | 76 |

| CRO_LTMA_30 | 263 | 166 | 375 | 213 | 252 | 299 | 309 | 279 | 171 | 182 | 252 | 201 | 286 | 325 |

| CRO_6 | 260 | 227 | 338 | 324 | 239 | 305 | 243 | 262 | 152 | 184 | 213 | 138 | 318 | 327 |

| MRFO | 189 | 328 | 237 | 271 | 207 | 222 | 114 | 148 | 196 | 97 | 104 | 369 | 166 | 330 |

| CRO | 136 | 175 | 268 | 93 | 150 | 222 | 218 | 164 | 144 | 112 | 168 | 160 | 175 | 311 |

| RS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A11.

LTMA(MsMA) Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

Table A11.

LTMA(MsMA) Draw Outcomes of MAs on Individual Problems in the CEC’24 Benchmark (F01–F15).

| F01 | F02 | F03 | F04 | F05 | F06 | F07 | F08 | F09 | F10 | F11 | F12 | F13 | F14 | F15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jDE_30 | 120 | 111 | 29 | 0 | 247 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| jDE_LTMA_30 | 120 | 111 | 43 | 0 | 245 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| jDE_LTMA_6 | 120 | 84 | 36 | 0 | 253 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 |

| jDE_LTMA_12 | 120 | 111 | 37 | 0 | 253 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |