Abstract

In this work, block checkerboard sign pattern matrices are introduced and analyzed. They satisfy the generalized Perron–Frobenius theorem. We study the case related to total positive matrices in order to guarantee bidiagonal decompositions and some linear algebra computations with high relative accuracy. A result on intervals of checkerboard matrices is included. Some numerical examples illustrate the theoretical results.

Keywords:

bidiagonal decomposition; high relative accuracy; total positivity; block checkerboard pattern MSC:

15B35; 15B48; 65F05; 65F15; 65G50

1. Introduction

Finding classes of structured matrices for which accurate computations can be assured has been a very active research field in recent years (cf. [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]). The desired goal is to guarantee high relative accuracy (HRA), and it has been achieved for the usual linear algebra computations only for a few classes of matrices. If an algorithm uses only additions of numbers of the same sign, multiplications, and divisions, on the assumption that each original real datum is known to HRA, then the output of that algorithm can be calculated with HRA (cf. [2] p. 52). Furthermore, in well-implemented floating-point arithmetic, HRA is preserved even when performing true subtractions with original exact data (cf. p. 53 of [2]). Therefore, an algorithm that only uses additions of numbers of the same sign, multiplications, divisions, and subtractions (additions of numbers of different sign) of the initial data ensures an output with HRA.

Among the sources of structured matrices for which HRA computations can be guaranteed are some subclasses of nonsingular, totally positive matrices. We say that a matrix is totally positive (TP) whenever all its minors are non-negative (see [8]). These matrices are also known as totally non-negative. TP matrices have been applied in many different fields (cf. [9,10,11,12]), including Approximation Theory, Statistics, Mechanics, Computer-Aided Geometric Design, Biomathematics, and Combinatorics, in addition to many other fields. A nonsingular TP matrix can be decomposed as a bidiagonal factorization, that is, it can be written as a product of bidiagonal matrices (see Chapter 7 of [10]). If we can compute this factorization with HRA, then we can apply the algorithms of [13] to perform many linear algebra computations with HRA, like the calculation of every eigenvalue, every singular value, and the inverse or solving some linear systems.

Many advantages of dealing with non-negative matrices are known. As recalled above, additional advantages can be obtained when dealing with TP matrices, in particular in the field of achieving HRA computations. In this paper, we show that the nice spectral properties of Perron–Frobenius theorems of non-negative matrices can be extended to some matrices with a special sign pattern. Analogously, we show how the HRA computations of some nonsingular TP matrices can be extended to some related classes of matrices with a special sign pattern.

The originality of the new results comes from the fact that this manuscript provides tools to identify new classes of matrices of different signs for which Perron–Frobenius-type theorems can be applied and for which high-relative-accuracy algorithms can be used. These matrices arise in Combinatorics, as shown in Section 6, but also in Computer-Aided Geometric Design or in Approximation Theory.

The structure of the paper is the following: Section 2 presents basic definitions, auxiliary results and the extension of Perron–Frobenius theorems to signed matrices. Section 3 introduces bidiagonal decompositions and the class of checkerboard matrices, whose advantages for achieving HRA computations are presented in Section 4. Section 5 includes a result on intervals of checkerboard matrices. Section 6 shows some examples of checkerboard matrices with integer entries whose bidiagonal decomposition can be extremely simple. Finally, Section 7 includes numerical experiments illustrating the accuracy of our methods with respect to standard methods.

2. Definitions and Auxiliary Results

Given a matrix A, we write if all its entries are non-negative. Let us introduce the notation for the set of strictly increasing sequences of r positive integers, and let . Then, we denote the submatrix of A that is formed by taking the rows numbered by and the columns numbered by as . If , submatrix is a principal submatrix of A, and it is written as . The dispersion number, , is defined for every as

So, consists of successive integers whenever .

Given a non-negative integer r, let us denote by the set of sequences of r positive consecutive indices such that for .

Definition 1.

We say that an infinite matrix has a block checkerboard sign pattern if for some positive integer r and all sequences of indices , we have that

Let us notice that the principal submatrices are non-negative for every .

In Definition 1, the parameter r describes the size of the sign blocks appearing in B. For the case , the sign structure of a block checkerboard pattern would be as follows:

We say that is a diagonal matrix if when . Hence, D can be represented in terms of its diagonal entries using the notation , where for .

The matrices introduced in Definition 1 have a particular block sign structure that can be captured using a sign matrix. Sign matrices are diagonal matrices such that . We will consider the particular case where . Then, we have the following characterization of infinite matrices with a block checkerboard sign pattern.

Proposition 1.

Given an infinite matrix , B has a block checkerboard sign pattern with blocks of size if and only if is a non-negative matrix.

We can build finite matrices with a block checkerboard sign pattern by taking principal submatrices with consecutive indices from the infinite matrices given by Definition 2.

Definition 2.

We say that is an r-checkerboard matrix if, given , for some sequence with and for some infinite matrix with a block checkerboard sign pattern given by (2).

An r-checkerboard matrix A can be identified in terms of an sign matrix K. In this case, the sign matrix would be given by , where is the sequence of indices for which A satisfies Definition 2. For this sign matrix K, we have that as a consequence of Proposition 1. Thanks to this property, we can deduce, for r-checkerboard matrices, some analogous results to the well-known Perron–Frobenius theorems.

Theorem 1

(cf. p. 26 in [14]). If is a non-negative square matrix, then the following apply:

- 1.

- The spectral radius of A, , is an eigenvalue of A;

- 2.

- A has a non-negative eigenvector that corresponds to .

Theorem 1 gives important information about non-negative matrices. For the case of r-checkerboard matrices, this result provides the following corollary.

Corollary 1.

If is an r-checkerboard matrix with an associated sign matrix K, then the following apply:

- 1.

- The spectral radius of A, , is an eigenvalue of A;

- 2.

- A has an eigenvector v that corresponds to such that is non-negative.

Proof.

Since , is an eigenvalue of by Theorem 1. The fact that implies that A and are similar matrices and that they have the same eigenvalues. Hence, is an eigenvalue of A. By condition 2 of Theorem 1, for a non-negative vector w. Hence, , and is an eigenvector corresponding to such that . □

3. Checkerboard Matrices and Bidiagonal Decomposition

In the previous section, we have seen that r-checkerboard matrices are similar to non-negative matrices thanks to sign matrices K. This relationship allowed us to deduce some spectral properties for r-checkerboard matrices. In this section, we will consider a stronger property, i.e., that is a nonsingular TP matrix. In that case, we obtain many interesting properties for this class of matrices, as well as the possibility of achieving accurate computations for solving many of the most common linear algebra problems with these matrices. The role of sign matrix K is fundamental. Let us start with the simplest case, which will showcase an important property of nonsingular TP matrices.

3.1. Checkerboard Pattern Matrices

Our first example of a sign matrix is diagonal matrix , that is, the matrix associated to an alternating sign pattern. If A is a checkerboard pattern matrix, then matrix is non-negative. For example, for the case ,

For the particular case where is a nonsingular TP matrix, we have that is also a nonsingular TP matrix (see Section 1 of [8]).

3.2. Two-Block Checkerboard Matrices

Now, we are going to focus on the -block case. Let us introduce sign matrix . For example, for , we have that

The sign structure associated to is formed by alternating blocks of entries with the same sign. A 2-checkerboard matrix A with a block sign structure associated to would be as follows:

Let us now define the counterpart to , i.e., sign matrix . For example, for , it takes the form

Once again, the associated sign structure to is formed by alternating blocks of entries with the same sign (leaving the first row and column as special cases). Hence, a 2-checkerboard matrix A with this pattern would be of the form

3.3. r-Block Checkerboard Matrices

Let us now extend the study to more general block structures: blocks with size . In this case, the sign matrix of an r-checkerboard matrix A takes the form for some , where t depends on sequence given by Definition 2. We are particularly interested in the case where r-checkerboard matrix A satisfies that is a nonsingular TP matrix. For this class of matrices, a parametrization that ensures computations with high relative accuracy is achieved through bidiagonal factorization.

Definition 3.

Let be an r-checkerboard matrix such that for some . Then, we say that A is a -checkerboard matrix if is nonsingular TP.

In this case, we have r different sign structures depending on the size of the block appearing on the upper left-hand corner of the matrix.

3.4. Bidiagonal Decomposition and SBD Matrices

Now, we will introduce the representation of a matrix in terms of bidiagonal decomposition. This factorization gives a unique representation of a nonsingular TP matrix that can be used to achieve many computations with HRA with this class of matrices.

Theorem 2

The bidiagonal decomposition given by Theorem 2 represents a TP matrix in terms of parameters. These parameters can be stored in an matrix according to the notation introduced in [15], where represented the bidiagonal decomposition of nonsingular TP matrix A:

Let us denote by a vector whose entries are only or , that is, with for all . This vector is called a signature. Based on the sign structure defined by the signature, in [16], a new class of matrices that admits a signed bidiagonal decomposition was introduced as an extension of nonsingular TP matrices that admit a unique bidiagonal decomposition. This class was called SBD matrices.

Definition 4.

Given a signature and a nonsingular matrix A, we say that A has a signed bidiagonal decomposition with signature ε if there exists a such that the following apply:

- 1.

- for all .

- 2.

- , and for all .

We say that A is an SBD matrix if it has a signed bidiagonal decomposition for some signature ε.

We will represent the bidiagonal decomposition of SBD matrices using the notation in (7). We can define a sign diagonal matrix associated to signature vector such that for all and for all . Let us observe that there are only two possible sign matrices K for any given , defined by either or . Hence, we can univocally identify with a sign matrix K such that . We can also characterize SBD matrices in terms of sign matrices K.

Proposition 2

(Corollary 3.2 of [16]). Let A be an nonsingular matrix. Then, A has a signed bidiagonal decomposition if and only if there exists a diagonal matrix with for all such that is a TP matrix, where represents a matrix whose entries are the absolute values of the corresponding entries of A.

This proposition implies that -checkerboard matrices are SBD matrices for the signature vector associated to sign matrix . Hence, -checkerboard matrices can be represented in terms of a bidiagonal decomposition according to Definition 4. For these matrices, the associated signature vector is , where

For a general -checkerboard matrix, the signature vector of its inverse is given by (see Theorem 3.1 of [16]). Hence, the sign structure of their inverses is related to the sign blocks appearing in the -block checkerboard matrices, and the following apply:

- If we look at the blocks appearing in the principal diagonal of the matrix, the interior of the blocks of positive entries breaks into positive blocks when we compute the inverse.

- The diagonal blocks that have positive diagonal entries and negative off-diagonal entries (corresponding to the end of a positive diagonal block and the start of the next one) turn into blocks of positive entries when computing the inverse.

In order to check this behavior, we should look at the signature vector associated to diagonal matrix . By Theorem 3.1 of [16], a matrix is SBD with signature if and only if its inverse is SBD with signature . For the case of -checkerboard matrices, their inverses are SBD matrices with signature . The negative entries in the signature vector imply that there is a change of sign in the associated sign matrix; hence, only blocks of positive entries appear in the principal diagonal of the inverse matrix. The only positive entries of the signature vector appear for the indices for , which implies that the sign matrix has two entries with the same sign; therefore, at those positions, we find blocks of positive entries.

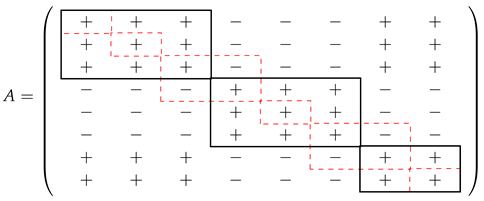

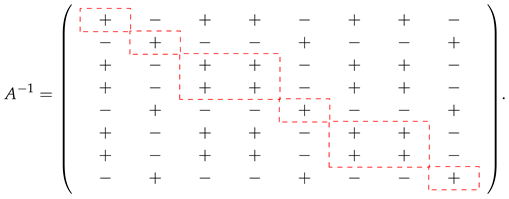

For example, for and , we have that the sign matrix of the inverse is . If we consider an r-checkerboard matrix A with the sign structure given by , we have that

- where the black squares denote the diagonal blocks of positive entries. The dashed-line squares show how the interior of these blocks break into blocks and the blocks appearing when a positive block finishes and the next one starts. Hence, the sign structure of the inverse would be as follows:

For the particular case of 2-checkerboard matrices, we have that the two only possibilities for sign patterns are closely related. For a -checkerboard matrix, the associated signature would be . For a -checkerboard matrix, its signature is . Hence, we have that , and we can obtain the following result by Theorem 3.1 of [16].

Corollary 2.

The inverse of a -checkerboard matrix is a -checkerboard matrix.

Proof.

If A is a -checkerboard matrix, then by Proposition 3.4, A is SBD with signature . By Theorem 3.1 of [16], a matrix is SBD with signature if and only if its inverse is SBD with signature . Therefore, is SBD with signature , which implies, by Proposition 3.4, that is nonsingular TP; so, is a -checkerboard matrix. □

4. Bidiagonal Decomposition of Checkerboard Matrices

Given a -checkerboard matrix A, we can multiply it from left and right by sign matrix to obtain a nonsingular TP matrix. Hence, their bidiagonal decompositions are related by the following formula:

If we know the bidiagonal decomposition of nonsingular TP matrix , we can obtain the bidiagonal decomposition of A thanks to formula (9). This formula also allows us to apply some of the HRA algorithms known for nonsingular TP matrices to this class of matrices, according to [16]. For nonsingular TP matrices, accurate computations can be achieved using bidiagonal decomposition (Theorem 2) as a parametrization. In [13,15], Plamen Koev designed algorithms to solve various linear algebra problems with nonsingular TP matrices with HRA by taking the bidiagonal decomposition as input. These algorithms have been implemented and are available in the library TNTool for use in Matlab and Octave. This library also contains later contributions by other authors and can be downloaded from Koev’s personal website [17]. For -checkerboard matrices, we can perform the following:

- Computing the eigenvalues of with HRA with the function TNEigenvalues in TNTool. The eigenvalues of A are the same, since they are similar matrices.

- Computing the singular values of with HRA using the function TNSingularValues. These singular values are also equal to the singular values of A, since and A coincide up to unitary matrices.

- Computing the inverse of with HRA with the function TNInverseExpand presented in Section 4 of [6] and available in TNTool. Then, we can obtain the inverse of A with HRA, since .

- Solving the system of linear equations with HRA whenever has an alternating pattern of signs, since is equivalent to , i.e., , where , using the function TNSolve.

5. Intervals of Checkerboard Matrices

This section will present a result on intervals of checkerboard matrices. Given diagonal matrix J and two matrices B and C, we can define the checkerboard ordering associated to J, . We say that if , where ≤ is the usual entry-wise inequality between two matrices. This ordering has proven to be quite useful in characterizing intervals of TP matrices. In [18], the following theorem, which identifies intervals of nonsingular TP matrices, was proven.

Theorem 3.

Let B and C be nonsingular TP matrices satisfying , i.e., . If A is an matrix such that , then A is nonsingular TP.

This idea has been extended to find orderings associated to SBD matrices in [19], and here, we analyze orderings for the case of checkerboard matrices. If a given matrix A is a -checkerboard matrix, we know that is nonsingular TP. Hence, we define the following ordering for -checkerboard matrices.

Definition 5.

Given two matrices, A and B, we define the ordering as if .

Now, we present a result on intervals of -checkerboard matrices based on the ordering .

Proposition 3.

Let B and C be -checkerboard matrices satisfying , i.e., . If A is an matrix such that , then A is a -checkerboard matrix.

Proof.

Since B and C are -checkerboard matrices, we have that and are nonsingular TP matrices that satisfy for an matrix A. Hence, by Theorem 3, is a nonsingular TP matrix, or equivalently, A is a -checkerboard matrix. □

6. Integer Examples

Many examples of TP matrices are ill conditioned. For instance, the symmetric Pascal matrix, whose -th entry is the binomial coefficient is a well-known example of ill-conditioning. However, the symmetric Pascal matrix admits a really simple representation in terms of the bidiagonal decomposition: all the nonzero entries of this factorization are ones. Hence, many linear algebra problems can be solved accurately with the Pascal matrix if we use algorithms that take the bidiagonal decomposition as input.

In this section, we are going to illustrate some examples of r-checkerboard matrices that admit an easy representation in terms of bidiagonal decomposition with integer entries.

6.1. Generalized Pascal Matrix

Our first example comes from an extension of the Pascal matrix depending on a parameter . The generalized -checkerboard Pascal matrix of the first kind, , is defined as the triangular matrix

and the symmetric generalized Pascal matrix, , is defined as

These matrices are the signed counterparts of the generalized Pascal matrix, , and the symmetric generalized Pascal matrix, (see [20]). Their bidiagonal decomposition are

respectively, where is given by (8) for . For the case , we have that these are examples of integer matrices.

6.2. Matrices of Stirling Numbers

Our next example comes from matrices of Stirling numbers. The Stirling numbers of the first kind () are the coefficients of the expansion of the falling factorial , i.e., , where . Let us recall that the Stirling numbers of the first kind can be calculated using the following recurrence relation:

where for , and for . Then, matrix is a -checkerboard matrix whose bidiagonal decomposition is given by

Matrix S is the inverse of a nonsingular TP matrix. That TP matrix is precisely the matrix whose entries are Stirling numbers of the second kind. Let us recall that the Stirling number of the second kind, , counts the different partitions of a set of n elements into k non-empty subsets. Hence, these numbers can be obtained by using the recurrence relation

with the initial conditions for , and for . Then, matrix is a nonsingular TP matrix whose bidiagonal decomposition takes the following form:

7. Numerical Experiments

In [13], Koev introduced methods to calculate the eigenvalues and the singular values of A and the solution of linear systems of equations , where b has a pattern of alternating signs from the parameterization for the case where A is a TP matrix. These algorithms provide approximations to the solutions of these algebraic problems with HRA if is obtained with HRA. In addition, in [6], Marco and Martínez developed an algorithm to calculate, with HRA, the inverse under the same previous hypotheses. In the software library TNTool, available in [17], these four algorithms are implemented with Matlab. The names of the corresponding functions are TNEigenvalues, TNSingularValues, TNInverseExpand, and TNSolve. They require, as input argument, bidiagonal decomposition of A, given by (7), with HRA. In addition, TNSolve needs vector b of the system of linear equations as a second argument. Regarding computational cost, the algorithms are at least as fast as the usual algorithms for solving these algebraic problems, as shown in the following:

- TNInverseExpand and TNSolve have both a computational cost of elementary operations.

- TNEigenValues and TNSingularValues both require elementary operations.

In order to illustrate the theoretical results, we considered the square matrices of order defined by (10), i.e.,

Table 1 shows the condition numbers of these matrices. It can be observed that these matrices are very ill conditioned. So, accurate results cannot be expected when using the usual algorithms for solving algebraic problems with them.

Table 1.

Condition numbers of .

It can be observed that is a -checkerboard matrix. In particular, it can be seen that , where is the symmetric generalized Pascal matrix defined by the absolute value of (10) for and is the order n matrix given by (4). Since is a TP matrix, taking into account the discussion in Section 4, the singular values and the inverse of , as well as the solution of systems , whenever has an alternating pattern of signs, can be computed with HRA. Observe that since is a symmetric matrix, the eigenvalues and the singular values of coincide. Since , the same applies to matrices .

The bidiagonal decomposition () of a generalized symmetric Pascal matrix can be computed with HRA for all by (11) (taking the case where for ). We implemented the algorithm for the computation of this bidiagonal decomposition in the Matlab function TNBDGPascalSym.

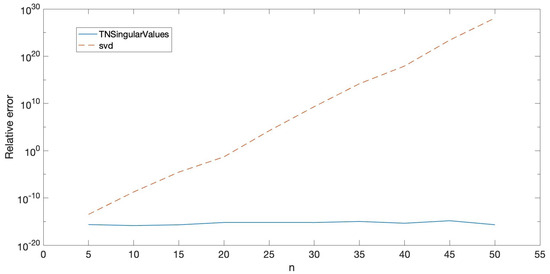

First, by using TNBDGPascalSym in Matlab, we calculated the bidiagonal decomposition () with high relative accuracy. Then, we computed approximations to the singular values of by using TNSingularValues with as input argument. Approximations to these singular values were also obtained with the Matlab function svd. In order to illustrate the accuracy of the approximations to the singular values computed by the two methods, the singular values of were also calculated with Mathematica using a precision of one hundred digits. Then, the relative errors for the approximations to the singular values obtained by both methods were computed, taking the singular values obtained with Mathematica as the exact singular values. These relative errors showed that the approximations of all the singular values calculated by using TNBDGPascalSym are highly accurate and that the approximations of the lower singular values computed by using the Matlab function svd are not very accurate. It was also observed that the lower the singular value is, the less accurate the approximation provided by svd is. To demonstrate this fact, the relative errors of the approximations to the smallest singular value of the considered examples (, ), obtained by both svd and TNSingularValues, are shown in Figure 1. From the results in that figure, it can be concluded that our method produces very accurate results, as opposed to the inaccurate results obtained with svd.

Figure 1.

Relative errors for the smallest singular value of .

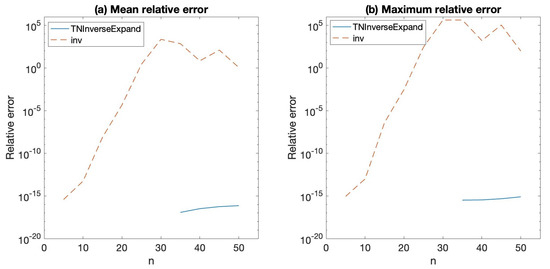

Approximations to , , were also obtained by using Matlab with inv and by using TNInverseExpand together with TNBDGPascalSym. The exact inverses, , were obtained with Mathematica using exact arithmetic. Then, the corresponding component-wise relative errors were computed. The mean relative errors are shown in Figure 2a, and the maximum relative errors are shown in (b). In this case, it is also clear that the accuracy of the results provided by TNInverseExpand is significantly better than that of the results provided by inv.

Figure 2.

Relative errors for , .

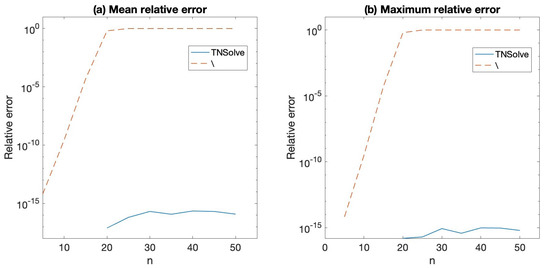

Finally, we considered the systems of linear equations , such that has an alternating pattern of signs and with entries whose absolute value is an integer randomly chosen in the interval . Then, approximations to the solution of these linear systems were computed in two ways: the first one, by using the Matlab command A\b, and the second one, by solving the system with TNSolve and then computing the solution of the original system as . The exact solutions of these systems were computed with Mathematica; then, the component-wise relative errors for both approximations were calculated. The mean relative errors are shown in Figure 3a, and the maximum relative errors are shown in (b). The results obtained with the HRA algorithms are much better from the point of view of accuracy than the results obtained with the usual Matlab method.

Figure 3.

Relative errors for the linear systems , .

In order to compare the computation time of the HRA methods with that of the usual methods, we solved the three algebraic problems considered in this section for one hundred times. Table 2 shows the average computation time for each one of the algebraic problems.

Table 2.

Average computation time in seconds.

8. Conclusions

We introduce the class of block checkerboard pattern matrices, which are matrices with a regular pattern of signs for which a generalized Perron–Frobenius type theorem is satisfied. We consider bidiagonal decomposition of checkerboard matrices for achieving linear algebra computations with high relative accuracy (HRA). These HRA computations include the calculation of all eigenvalues and all singular values, the calculation of the inverses, and the solution of some associated linear systems. We also introduce a new order relation for matrices, deriving a result on intervals of block checkerboard matrices. We present new families of matrices with integer entries, which can be used as test matrices to check the accuracy of linear algebra algorithms. Numerical examples illustrate the accuracy of the presented methods compared with standard methods for the abovementioned linear algebra computations.

Author Contributions

J.D., H.O. and J.M.P. authors contributed equally to this research paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported under the Spanish research grants PID2022-138569NB-I00 and RED2022-134176-T (MCIU/AEI) and by Gobierno de Aragón (E41_23R).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TP | Totally positive |

| HRA | High relative accuracy |

References

- Demmel, J.; Dumitriu, I.; Holtz, O.; Koev, P. Accurate and efficient expression evaluation and linear algebra. Acta Numer. 2008, 17, 87–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmel, J.; Gu, M.; Eisenstat, S.; Slapnicar, I.; Veselic, K.; Drmac, Z. Computing the singular value decomposition with high relative accuracy. Linear Algebra Appl. 1999, 299, 21–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmel, J.; Koev, P. The accurate and efficient solution of a totally positive generalized Vandermonde linear system. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2005, 27, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Martínez, J.J. A fast and accurate algorithm for solving Bernstein-Vandermonde linear systems. Linear Algebra Appl. 2007, 422, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Martínez, J.J. Accurate computations with Said-Ball-Vandermonde matrices. Linear Algebra Appl. 2010, 432, 2894–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Martínez, J.J. Accurate computation of the Moore-Penrose inverse of strictly totally positive matrices. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 350, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, A.; Martínez, J.J.; Viaña, R. Accurate bidiagonal decomposition of totally positive h-Bernstein-Vandermonde matrices and applications. Linear Algebra Appl. 2019, 579, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T. Totally positive matrices. Linear Algebra Appl. 1987, 90, 165–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantmacher, F.P.; Krein, M.G. Oscillation Matrices and Kernels and Small Vibrations of Mechanical Systems: Revised Edition; AMS Chelsea Publishing: Providence, RI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gasca, M.; Micchelli, C.A. (Eds.) Total Positivity and Its Applications, Volume 359 of Mathematics and Its Applications; Kluwer Academic Publishers Group: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, S. Total Positivity; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1968; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkus, A. Totally Positive Matrices; Tracts in Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Volume 181. [Google Scholar]

- Koev, P. Accurate computations with totally nonnegative matrices. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2007, 29, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.; Plemmons, R.J. Nonnegative Matrices in the Mathematical Sciences; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Koev, P. Accurate eigenvalues and SVDs of totally nonnegative matrices. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2005, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreras, A.; Peña, J.M. Accurate computations of matrices with bidiagonal decomposition using methods for totally positive matrices. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2013, 20, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koev, P. Available online: http://www.math.sjsu.edu/~koev/software/TNTool.html (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Adm, M.; Garloff, J. Intervals of totally nonnegative matrices. Linear Algebra Appl. 2013, 439, 3796–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreras, A.; Peña, J.M. Intervals of structured matrices. In Monogr. Mat. García Galdeano; Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2016; Volume 40, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, J.; Orera, H.; Peña, J.M. Accurate bidiagonal decomposition and computations with generalized Pascal matrices. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 391, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).