Abstract

We compare the classical viscoelastic models due to Becker and Lomnitz with respect to a recent viscoelastic model based on the Lambert W function. We take advantage of this comparison to derive new analytical expressions for the relaxation spectrum in the Becker and Lomnitz models, as well as novel integral representations for the retardation and relaxation spectra in the Lambert model. In order to derive these analytical expressions, we have used the analytical properties of the exponential integral and the Lambert W function, as well as the Titchmarsh’s inversion formula of the Stieltjes transform. In addition, we prove some interesting inequalities by comparing the different models considered, as well as the non-negativity of the retardation and relaxation spectral functions. This means that the complete monotonicity of the rate of creep and the relaxation functions is satisfied, as required by the classical theory of linear viscoelasticity.

Keywords:

laplace transform; stieltjes transform; exponential integral; Lambert W function; linear viscoelasticity models MSC:

44A10; 33E20

1. Introduction

According to the theory of linear viscoelasticity, a material under a unidirectional loading can be represented as a linear system where either stress, , or strain, , serve as input (excitation function) or output (response function), respectively. Considering that stress and strain are scaled with respect to suitable reference states, the input in a creep test is , while in a relaxation test, it is , where denotes the Heaviside function. The corresponding outputs are described by time-dependent material functions. For the creep test, the output is defined as the creep compliance , and for the relaxation test, the output is defined as the relaxation modulus . Experimentally, is always non-decreasing and non-negative, while is non-increasing and non-negative.

According to Gross [1], it is quite common to require the existence of non-negative retardation and relaxation spectra for the material functions and , respectively. These functions are defined as ([2], Equation (2.30b))

From a mathematical point of view, these requirements are equivalent to state that is a Bernstein function and that is a completely monotone (CM) function. We recall that the derivative of a Bernstein function is a CM function, and that any CM function can be expressed as the Laplace transform of a non-negative function, that we refer to as the corresponding spectral function or simply spectrum. For details on Bernstein and CM functions, we refer the reader to the excellent treatise by Schilling et al. [3].

In order to calculate and from and , Gross introduced the frequency spectral functions and , defined as ([2], Equation (2.32))

where . Therefore, taking the scaling factors , we have

and

In the existing literature, many viscoelastic models for the material functions and have been proposed in order to describe the experimental evidence. The first pioneer to work on linear viscoelastic models was Richard Becker (1887–1955). In 1925, Becker introduced a creep law to deal with the deformation of particular viscoelastic and plastic bodies on the basis of empirical arguments [4]. This creep law has found applications in ferromagnetism [5], and in dielectrics [1]. This model has been generalized in [6] by using a generalization of the exponential integral based on the Mittag–Leffler function. In 1956, Cinna Lomnitz (1925–2016) introduced a logarithmic creep law to treat the creep behaviour of igneous rocks [7]. This law was also used by Lomnitz to explain the damping of the free core nutation of the Earth [8], and the behavior of seismic S-waves [9]. In order to generalize the Lomnitz model, Harold Jeffreys introduced a new model depending on a parameter in 1958 [10]. When , the Jeffreys model is reduced to the Lomnitz model. In ([2], Section 2.10.1), the Jeffreys model is extended to negative values of . Very recently, the authors have proposed a new model based on the Lambert W function [11]. In order to evaluate the principal features of this new model, the main aim of the paper is to compare it with respect to the Becker and Lomnitz models, since these classical models have several applications and generalizations in the literature.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce some basic concepts of linear viscoelasticity that will be used throughout the article. We present the dimensionless relaxation modulus , as well as the frequency spectral functions and in terms of the Laplace transform. Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 are devoted to the derivation of analytical expressions for , as well as and in Becker, Lomnitz, and Lambert models, respectively. As far as the authors are aware, the closed-form expressions found for in Becker and Lomnitz models are novel. Also, the integral expressions found for and in the Lambert model are also novel. In Section 6, we graphically compare the models considered here. Finally, we present our conclusions in Section 7.

2. Essentials of Linear Viscoelasticity

In Earth rheology, the law of creep is usually written as

where t is time, is the unrelaxed compliance, q is a positive dimensionless material constant, and is the dimensionless creep function. Note that the scaling factor q takes into account the effect of different types of materials following the same creep model, i.e., the same dimensionless creep function . Since , we have

The dimensionless relaxation function is defined as

where is the relaxation modulus. Note that acts as a scaling factor for the dimensionless relaxation modulus . This dimensionless relaxation function obeys the Volterra integral equation ([2], Equation (2.89)):

From (8), we have

Assuming , the solution of (8) is (see Appendix A)

where denotes the Laplace transform of the function and is its inverse Laplace transform.

Frequency Spectral Functions

From the definitions given in (1)–(4), we can derive that the creep rate can be expressed in terms of the frequency spectral function as (see ([2], Equation (2.35)))

and the relaxation modulus rate can be expressed in terms of the frequency spectral function as

On the one hand, taking the scaling factors and , and differentiating in (7), we have that

thus,

where denotes the Stieltjes transform ([12], Equation (1.14.47)). Applying Titchmarsh’s inversion formula ([13], Section 3.3), we obtain

Apply Titchmarsh’s inversion formula again to arrive at

Finally, according to (10), we have

3. Becker Model

The law of creep for the Becker model is

where the complementary exponential integral is defined as ([12], Equation (6.2.3))

whereby this function is an entire function. For simplicity, we take the scaling factor ; thus,

Taking and in the following Laplace transform ([14], Equation (2.2.4(14))):

we conclude that

3.1. Frequency Spectral Functions

For , we have that ; hence,

where denotes the principal argument of . Therefore,

Consider . Note that , we have . Also, , we have

and so we conclude

3.2. Retardation and Relaxation Spectra

4. Lomnitz Model

The law of creep in the Lomnitz model is [7]

For simplicity, we take the scaling factor ; thus,

Let us calculate the Laplace transform of . Indeed,

Perform the change in variables and to obtain

i.e.,

where denotes the exponential integral ([12], Equation (6.2.1)). According to (10) and (23), the dimensionless relaxation modulus is given by

4.1. Frequency Spectral Functions

The exponential integral function can be expressed as ([12], Equation (6.2.2))

where denotes the Euler–Mascheroni constant. Since the power series of the complementary exponential integral is given by ([12], Equation (6.6.4))

it is apparent that

Therefore, , we have

so that

4.2. Retardation and Relaxation Spectra

5. Lambert Model

The law of creep in the Lambert model is [11]

where denotes the principal branch of the Lambert W function ([12], Section 4.13). The Lambert W function is defined as the root of the transcendental equation:

Differentiating in (31), it is easy to prove that

Taking into account (32), the Laplace transform of the creep rate is

thus, according to (10), we have the following for the Lambert model:

Retardation and Relaxation Spectra

Unfortunately, an analytical expression for the Laplace transform of the Lambert W function is not known, and so, the dimensionless relaxation modulus has to be numerically evaluated, as well as the frequency spectral functions:

from which we obtain the retardation and the relaxation spectra, respectively:

Perform the change in variables to obtain

For , we have

thus,

In addition, if we take into account (20), we conclude that

Similarly, we obtain

For , we have

thus,

6. Numerical Results

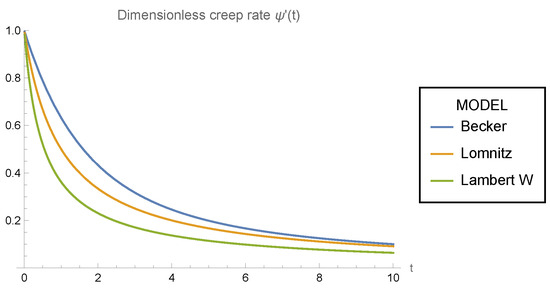

Figure 1 shows the dimensionless creep rate for the Becker (15), Lomnitz (22), and Lambert (33) models. It is apparent that for , is a monotonic decreasing function in all models, with . Also, Figure 1 suggests that for . The latter can be derived very easily by analytical methods, as it is shown in Appendix C.

Figure 1.

Dimensionless creep rate.

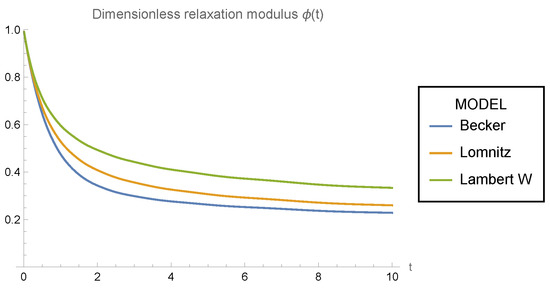

In Figure 2, the dimensionless relaxation modulus is plotted for all the models considered here. For this purpose, we have numerically evaluated (17), (24), and (34), computing the inverse Laplace transform with the Papoulis method [15] integrated into MATHEMATICA . It is apparent that is a monotonic decreasing function for with (9). Also, Figure 2 suggests that for . Unlike the case of the creep rate, it does not seem that any analytical method derives the latter inequality.

Figure 2.

Dimensionless relaxation modulus.

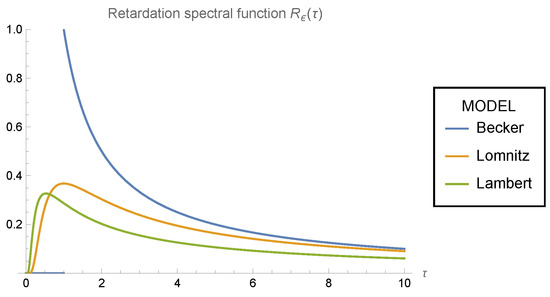

Figure 3 presents the retardation spectral function for the Becker (20), Lomnitz (29), and Lambert (37) models. It is worth noting that the graphs corresponding to the Lambert and Becker models verify the inequality derived in (40), i.e., for .

Figure 3.

Retardation spectral function .

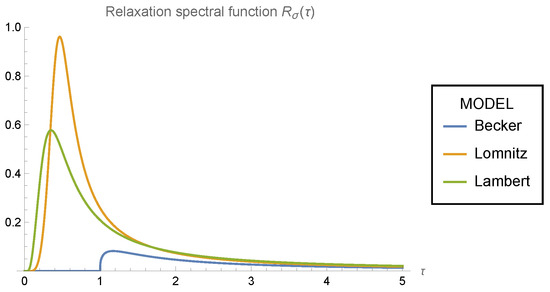

In Figure 4, the relaxation spectral function is plotted for the Becker (21), Lomnitz (30), and Lambert (41) models. Despite the fact that the plots for and are quite similar for all the models, there is a great qualitative difference between the Becker model, and the Lomnitz and Lambert models with respect to the spectral functions and , since the Becker model shows a discontinuity at , but we have continuous functions for the other two models.

Figure 4.

Relaxation spectral function .

Finally, according to Figure 3 and Figure 4, it is apparent that the retardation and relaxation spectra for all the models considered here are non-negative functions, as aforementioned in the Introduction section. This is consistent with what was said above in (20) and (21) for the Becker model, (29) and (30) for the Lomnitz model, and (39) and (42) for the Lambert model.

7. Conclusions

We have compared some of the viscoelastic models for the law of creep reported in the literature, i.e., the Becker, Lomnitz, and Lambert models. For these models, we have computed in a much more efficient way the dimensionless relaxation modulus by numerically evaluating the inverse Laplace transform that appears in (10) instead of numerically solving the Volterra integral equation given in (8) (see ([2], Section 2.9.2)). The numerical inversion of the Laplace transform has been carried out by using the Papoulis method [15].

For the Becker and Lomnitz models, we have given novel closed-form formulas for the relaxation spectrum , i.e., Equations (21) and (30). It is worth noting that these closed-form formulas allow us to compute in a much more efficient way than the numerical inversion of (2). As aforementioned in the Introduction section, the Becker and Lomnitz models have been considered in many physical applications; thus, these closed-form formulas are quite valuable in the field of viscoelastic materials.

Also, as a novelty, we have derived the retardation and relaxation spectra and in integral form for the Lambert model in (37) and (41). Again, these integral representations allow us to compute and very efficiently.

Further, we have proven that the spectral functions and are non-negative functions for all the models considered. It is worth noting as well that we have proven the interesting inequality for when comparing the retardation spectrum of the Lambert and Becker models.

In addition, we have compared all the models in terms of the behaviour of the dimensionless creep rate in Figure 1, as well as the dimensionless relaxation modulus in Figure 2, and the spectral functions and in Figure 3 and Figure 4. From these graphs, we can appreciate that all the models are asymptotically equivalent, although not at the same rate. It is worth noting that the Becker model presents a discontinuity in the retardation spectral functions and at , which is not present in the other models.

Finally, in Appendix C, we have proven the following inequality for the creep rate:

However, the following inequality for the dimensionless relaxation modulus:

which is suggested in Figure 2, seems to be true, but we could not find any mathematical proof for it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M.; methodology, F.M.; software, J.L.G.-S.; validation, J.L.G.-S.; formal analysis, J.L.G.-S.; investigation, J.L.G.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.G.-S.; writing—review and editing, F.M.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors dedicate this article to their colleague, Paolo Emilio Ricci, on the occasion of his 80th birthday. We also thank the reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which have helped to improve this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Calculation of ϕ(t)

Let us solve (8), taking , i.e.,

In order to calculate (A1), let us introduce the convolution theorem for the Laplace transform ([16], Theorem 2.39).

Theorem A1

(convolution theorem). If f and g are piecewise continuous on and of exponential order α, then

where the convolution is given by the integral

Therefore, applying the Laplace transform to (A1), we obtain

Solving for , we conclude that

Appendix B. The Imaginary Part of the Lambert Function for Negative Values

We want to bound the imaginary part of the principal branch of the Lambert W function for negative values of the argument, i.e., for . Consider , so that . If , and , we have that

thus,

If , i.e., , we have or . The case is not interesting for our purpose, since . Therefore, insert in (A3) to obtain

Note that is an even function. Moreover,

and

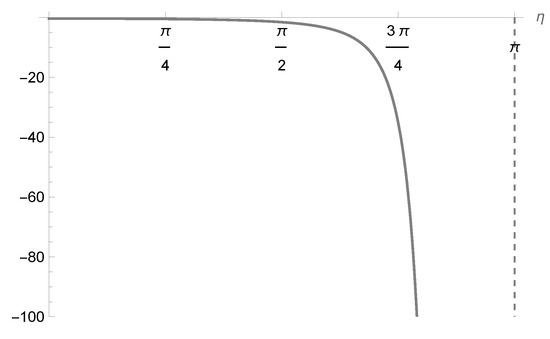

Since Figure A1 shows that is a monotonic decreasing function for , we obtain the following bound:

Moreover, since for ([12], Section 4.13), we conclude that

Figure A1.

Function .

Appendix C. The Creep Rate Inequality

On the other hand, consider and . Since , and is a convex function, we have that

From (A7), we have for the following:

Consequently,

References

- Gross, B. Mathematical Structure of the Theories of Viscoelasticity; Hermann & C: Paris, France, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity: An Introduction to Mathematical Models, 2nd ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022; [1st edition 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, R.L.; Song, R.; Vondraček, Z. Bernstein Functions: Theory and Applications; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, R. Elastische nachwirkung und plastizität. Z. Phys. 1925, 33, 185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Döring, W. Ferromagnetismus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi, F.; Masina, E.; Spada, G. A generalization of the Becker model in linear viscoelasticity: Creep, relaxation and internal friction. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2019, 23, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomnitz, C. Creep measurements in igneous rocks. J. Geol. 1956, 64, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomnitz, C. Linear dissipation in solids. J. Appl. Phys. 1957, 28, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomnitz, C. Application of the logarithmic creep law to stress wave attenuation in the solid earth. J. Geophys. Res. 1962, 67, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, H. A modification of Lomnitz’s law of creep in rocks. Geophys. J. Int. 1958, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, F.; Masina, E.; González-Santander, J.L. A note on the Lambert W function: Bernstein and Stieltjes properties for a creep model in linear viscoelasticity. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, F.W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F.; Clark, C.W.; Miller, B.R.; Saunders, B.V.; Cohl, H.S.; McClain, M.A. (Eds.) NIST Digital Library of Mathematical Functions. Release 1.2.0 of 15 March 2024. Available online: https://dlmf.nist.gov (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Apelblat, A. Laplace Transforms and Their Applications; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prudnikov, A.P.; Brychkov, I.A.; Marichev, O.I. Integrals and Series: Direct Laplace Transforms; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1986; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Papoulis, A. A new method of inversion of the Laplace transform. Q. Appl. Math. 1957, 14, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, J.L. The Laplace Transform: Theory and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).