Abstract

This paper proposes an icon-based methodology for the design of prototype aggregated production planning software that addresses the complexity of multi-process and multi-product production. Aggregate planning is a critical task in production management, which involves coordinating the production of multiple products in different processes to meet demand efficiently. The approach focuses on the use of visual icons to represent key elements of the production process, such as products, processes, resources, and constraints. These icons allow an intuitive representation of information and facilitate communication between production team members. In addition, this paper presents a conceptual structure that defines the relationships between the icons and how they are used to model and simulate aggregate production planning. The prototype software based on a conceptual foundation allows planners to easily create and adjust production plans in a visual environment. This method improves the ability to make informed and rapid decisions in response to changes in demand or production capacity. The prototype is based on icons and programmed in Excel spreadsheets to facilitate the planner’s planning. At the end of the document, the application of a case study is shown.

MSC:

90-04

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Topics

The production industry continuously faces planning challenges to avoid, among other problems, stockouts, or unfulfilled orders. The motivation behind the creation of this document is to provide productive companies with a simpler way to plan their production for decision making, without neglecting the mathematical tools that enable optimal planning. This motivation arises from the need to streamline the construction of the mathematical model and subsequent computational model essential for production planning and scheduling. This operation entails building a complex mathematical and computational model, requiring highly trained and costly personnel. Therefore, a graphic method based on icons has been conceived to allow for an intuitive and visual construction of the model. These icons form the core of this project and have been successfully incorporated into small-scale test software, demonstrating the achievement of the goal to simplify planning. Another equally important motivation is to contribute to the digital transformation of resource-constrained productive enterprises, such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), through the use of everyday tools within business practices, such as Excel spreadsheets. These motivations stem from the desire to enhance the productivity of the industrial sector as a contributing factor to the economic development of the operational region. This research proposes to address production inefficiencies through aggregated production planning from a simplified point of view. Production planning is a fundamental pillar in industry; specifically, aggregate production planning (APP) allows for the determination of production, inventory, and workforce level when demand is dynamic and for a planning horizon of up to one year [1]. By using different strategies and methodologies, the APP solution can be utilized to control and plan production activity, with the aim of achieving the minimum total cost and at the same time, the best allocation of resources such as machine capacity, available storage, and worker capacity. Classical strategies for production planning and control consider changing the size of the workforce, changing the production rate, consolidating seasonal inventories, planning and allowing back-orders, sub-contracting, and influencing demand [2]. This research uses the first three strategies.

The solution of APP has been classically achieved using tabular and graphical methods and mathematical methods; an example of this approach can be seen in [3]. In this paper, we present a conceptual framework that serves as a basis for the design of a methodology that is applied by using a computational tool to allow a user to solve APP problems in an optimal way that does not require knowledge of linear programming. Classical strategies and mathematical methods from operations research are used, reducing the complexity of the mathematical modeling of the target production system. This conceptualization is based on icons that allow representation of the plant layout, the inventories, the available resources of machine capacity, labor force level, the processes and the machines involved in the production, and the forecasted demand. In this article, icons are conceived as editable data containers where the user can emulate a target production system in an initial spreadsheet by activating and deactivating icons. Once the data are loaded into the icons, the APP mathematical model is automatically generated, and the exact solution of the mixed-integer linear programming (MIP) problem with logical decisions can be obtained by using a solver for a given time horizon.

In the literature, we can find the following classification of production systems: job shop, batch flow, operator-paced line flow, continuous flow, just-in-time, and flexible manufacturing system [4]. It is expected that the proposed tool can be adapted to the six classification types. However, and as an initial scope, a case study with a batch flow production system with multiple processes and products is presented. In addition, a solution is presented with a prototype of the proposed tool. For this purpose, a taxonomy of icons is proposed to model an APP problem, and, as a consequence, a tool that requires the input of the production system data was obtained, reducing the complexity of mathematical modeling by means of visual programming with icons and virtual figures. The authors hope that the usefulness of this tool will mainly empower small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) and/or companies with low investment resources and low levels of technological development, allowing the planning and control of their production activities.

The main contributions of this work are to propose a methodology, based on an iconic conceptualization, and to build a mathematical model that supports the scheduling of activities associated with the aggregate planning of operations. The method can also be employed by users without knowledge of linear programming. This is mainly relevant in SME companies lacking the resources to invest in trained personnel or in a consulting service to generate technological development. Through the application of a computational tool, the methodology can visually represent the target production system with virtual icons. In this approach, the user does not need to know the techniques of the mathematical optimization approach, which is characterized by constraints and an objective function, and only needs to learn the visual language of the icons and pictures of the proposed tool to represent the production process as if it were a flowchart. In other words, the icons can reproduce the plant layout to build the APP model.

To validate the methodology and its conceptualization, a small-scale prototype was built within a spreadsheet, so that any company including SMEs can use it. This prototype has the basic functions to solve an APP problem. In the following, the literature review and problem definition sections are presented, then the definitions and structure of the proposed methodology section are introduced, and then we proceed to the section in which a case study is presented. Finally, the results and conclusions are presented.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Aggregate Production Planning

The literature on APP is abundant. In 1975, Eilon published an early short review demonstrating five solution approaches for APP problems [5]. More recently in 2019, Cheraghalikhani et al. published a review of the last 27 years, classifying APP models into two groups, deterministic models and uncertain models [6]. Of those falling into the uncertain model classification, Jamalnia et al. [7] reviewed the uncertainty handling methods in depth. For the deterministic model’s classification, a comprehensive review of the APP problem from a circular economy and sustainability perspective was published in early 2022 by Aydin et al. [8]. The authors emphasized that in order to meet the environmental and social sustainability criteria in the planning period, the principles of the circular economy can be used; their work is the first systematic review of the last 50 years of APP research and offers a classification of the papers by the type of objective function. Table 1 shows the most recent studies and research where the criterion used for the search was the aggregate production planning problem and scheduling problem.

Table 1.

Recent research on aggregate production planning.

In the literature reviewed, no methodologies were found to reduce the complexity of mathematical modeling in APP problems.

1.2.2. Computational Tools

Penlesky and Srivastava (2007) published software that solves APP problems using a spreadsheet; however, unlike the optimal solution proposed by the prototype of this research, they solved the problem with the “trial and error” method [41]. More recently, in 2021, Rehman et al. published a work on optimizing APP problems with two models: with and without productivity loss. Their work was programmed in Python, and the code can be read in the publication [26]. Regarding software testing in real cases, we will mention some cases. In 2001, Brown et al. described the application of planning software for the Kellogg’s Company; according to the authors, the production and inventory costs were markedly reduced, in addition to facilitating decision making in the short and medium term [42]. In 2015, Zago and Mezquita implemented a production planning and scheduling software for a Brazilian dairy company. The results were promising; they managed to increase control over inventory levels and reduce costs associated with the process [43].

Another study published in 2015 by Jonsson and Ivert warns that, at least in the Swedish industry, only a small number of companies use a sophisticated method to plan production and concludes that the use of advanced methods allows for more feasible plans [44]. It is worth mentioning that not everything is conducive to the prototype proposed in this research, since it has been designed with Excel spreadsheets. In 2011, Vlckova and Patak examined the planning practices of four food industries using Excel spreadsheets; they concluded that effective planning can only be achieved with an integrated information system [45]. On the web, commercial software is available that offers APP among other services. Table 2 shows some examples of this software with the pages where they can be purchased.

Table 2.

Some commercial production planning software examples.

1.3. Problems and Contributions

The Latin American region faces the challenge of increasing the productivity of its industries to generate economic and social development, and this challenge is particularly difficult for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). In the region, 99% of formal companies are MSMEs, and 61% of jobs are generated by them. Despite the above, the contribution to GDP observed in 2020 is only 25%, a far cry from the 56% contribution observed in the European Union [46]. Between 2000 and 2019, the world’s large and dynamic economies such as China and the United States experienced economic growth in which productivity contributed 96% and 64%, respectively. In Latin America, only 24% of economic growth was contributed by productivity in the same years [47]. In particular, the manufacturing industry provides employment to 12.8% of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean. The sector’s contribution to GDP is 12.6% on average, considering differences between countries [48].

In part, the region has not been able to take advantage of the information and telecommunications technology (ICT) revolution and is behind in the implementation of Industry 4.0 methodologies. On the other hand, business legislative regulation is different in Latin America than in the countries and regions compared above [49]. In production companies in Latin America, the lack of efficient planning is a recurrent problem and it affects the productivity of machines and workers, the use of raw materials, and the achievement of economic goals, among other negative effects. It also leads to stockouts, which affects the relationship with the distribution channels and affects costs and therefore the entire business. In addition, most small and medium-sized companies in Latin America do not have technically and professionally trained personnel capable of operating operations scheduling methods and software.

Evidence of the weaknesses above is the information provided in a study by the Chilean Association of Engineers, whose president, Mr. Fernando Agüero, indicates that less than 3% of companies have an engineer and that the only sector where 4% of companies have engineers is the food industry [50]. The situation is similar in Mexico, where about 24,000 engineers graduate each year, while in developed countries there are about 60,000 graduates [51]. For this reason, the aim of this work was to provide a conceptualization that facilitates the construction of the APP mathematical computational model without necessarily being operated by an experienced engineer. This conceptualization is intended to allow a technician without a specialty in operations research and/or computer science to generate the production program. The idea is that from the knowledge of the production process, using the definition of process icons, sub-processes, resources, parameters, and layout, the user can generate the mathematical model implicitly. That is, without realizing that they are writing a mathematical model, just following the logic of the visual planning methodology, the user can be able to generate the appropriate model for the specific situation.

Associated with this methodology and conceptualization, a simple prototype has been developed to illustrate the application and demonstrate its function with this new approach. The prototype is a DSS that follows the methodology, and it is implemented on an Excel spreadsheet, which has three sheets. In the first one, the general layout of the plant is defined, and the process parameters are entered, such as costs, demand, inventories, and resources. In the second sheet, the information is summarized, and in the third one, the solver is executed delivering the aggregated production plan.

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

- Proposing a methodology based on icons to obtain optimal aggregate production plans without the need to perform mathematical modeling;

- Suggesting a prototype that applies the icon-based methodology to achieve optimal production planning based on the flowchart representation of a target production system and its information;

- Providing companies without sufficient resources to invest in ICT, a tool to improve their productivity;

- Noting that visual modeling using icons can be used to implement different engineering methodologies, simplifying their application.

2. Definitions and Structure of the Methodology

2.1. Icon-Based Methodology

In industrial production, it is necessary to plan how much and when to produce in order to meet the demand, considering limitations in available resources such as labor force, machine capacity, and inventory space.

When the production plan is generated by using an operations research tool, then it is optimal and allows the objective to be achieved at a minimum total cost.

This study proposes an optimal aggregate production planning tool for production systems with multiple products and multiple processes, based on icons. The editable figure containing the data matrix to be entered is represented by a virtual icon. A prototype implemented on an Excel spreadsheet is presented. With this methodology, the complexity of the mathematical modeling process involving the formulation of the objective function and constraints is reduced.

The tool is a DSS called Icons-Based Methodology for Aggregate Production Planning (hereinafter IBPlanner) and has been designed to be applied in steps as described below:

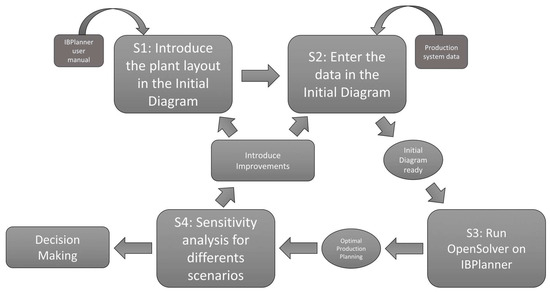

Step 1 (S1): Introduce in an Initial Diagram the distribution and physical arrangement of the machines, stages, and/or workstations, which we will henceforth understand as the sub-processes of the different working lines of the production process. This corresponds to the first stage of the methodology as shown in Figure 1. The spatial configuration of the factory is obtained from a flowchart of the production process or directly from the layout of the plant; the important issue is that the user knows their production process well and ideally is able to make a flow diagram, thus facilitating the visual modeling. By activating and deactivating specific cells of the Initial Diagram spreadsheet, it is possible to enable or disable work lines to reproduce the plant layout, which allows IBPlanner to be adaptable for multiple companies. We understand the work lines as parallel processes that can deliver the various products independently.

Figure 1.

Proposed methodology for using IBPlanner.

Step 2 (S2): Enter the data of the production process in the Initial Diagram. The following data are required:

- a.

- For each product in each desired planning period, the following are required:

- i.

- Demand in units;

- ii.

- Unit cost to inventory and available inventory capacity.

- b.

- For each sub-process of each work line, in each planning period and for each product, the following are required:

- i.

- Unit cost of production;

- ii.

- Machine hours required per unit;

- iii.

- Worker hours required per unit.

- c.

- Machine hours and worker hours available for all planning periods and for each work line, as applicable. This is understood as the number of hours operated by a machine or worker in a sub-process for the manufacture of a unit of the product.

Step 3 (S3): Solve the model by obtaining the optimal production and inventory planning by product and by period using the Excel OpenSolver add-in.

Step 4 (S4): Analyze the detailed information for each work line regarding the use of its resources and capacities for decision making by performing sensitivity analysis for different scenarios to facilitate decision making.

Once the stages of the methodology have been completed, it is possible to introduce improvements in the Initial Diagram that respond to changes in the conditions of the productive environment, for example, an investment in capacity, or changes suggested by the analysis of Step 4. This allows the use of IBPlanner to be iterative in the search for optimal planning.

2.2. Mathematical Model and Icons of the Initial Diagram

Before presenting the icons of the diagram and the model, we will define the following indexes, variables, and parameters with which the icons work:

Indexes

- t = 1, 2, …, T index of planning periods;

- i = 1, 2, …, N index of products;

- j = 1, 2, …, J index of work lines;

- k = 1, 2 index of Resources, k = 1 (machine hours), k = 2 (worker hours);

- l = 1, 2, …, L index of serial sub-processes;

- p = 1, 2, …, P index of parallel sub-processes.

Variables

- ➢

- Xijt—Number of product units i manufactured by work line j in period t;

- ➢

- Iit—Number of product units i in inventory at the end of period t.

Parameters

- ➢

- Dit—Forecast of units demanded of the product i in a period t;

- ➢

- Hit—Inventory cost for a product unit i in period t;

- ➢

- Cijt—Cost of producing a unit of product i in process j and period t;

- ➢

- ccijlt—Cost of producing a unit of product i in process j, stage l, and period t;

- ➢

- cccijplt Cost of producing a unit of product i, process j, stage l, parallel machine p, and period t;

- ➢

- Rkjt—Amount available of resource k for work line j in period t;

- ➢

- rkij—Required amount of resource k per unit of product i if processed in j;

- ➢

- rrkilj—Required amount of resource k for a product unit i processed in stage l of process j;

- ➢

- rrrkiplj—Required amount of resource k for a unit of product i processed in stage l of process j on the parallel machine p.

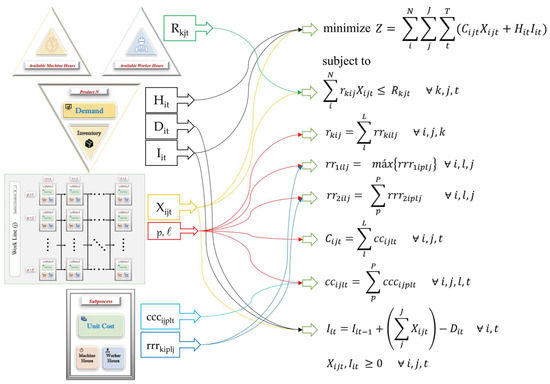

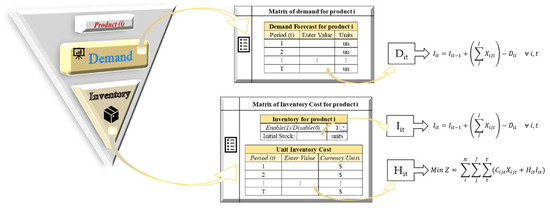

The model used in the planning tool is multi-process and multi-product. Figure 2 shows the methodology icons and a summary of the equations used, graphically representing the idea that each virtual icon contributes with variables and parameters to the model configuration. The model has an objective function that minimizes the total cost of production and inventory in the desired planning horizon and capacity constraints of the resources machine hours and worker hours; it also has inventory and demand constraints that apply to each product in each time period. The cost constraints collect unit information for each serial or parallel sub-process. The model allows the different products to be manufactured in all work lines or only in a subset of them. It does not consider the possibility of a product changing work line in the middle of manufacturing execution. Each work line can have multiple stages, where there can be serial and parallel configurations for the machines. As initial research, it does not consider setup costs, but this is not ruled out in future implementations. Some logical decisions are not shown in Figure 2, but in the prototype tool, there are switches that activate and deactivate the work lines.

Figure 2.

Virtual icons of the IBPlanner tool and its contribution of variables and parameters to the main constraints and objective function of the mathematical model that solves the APP problem.

The unit cost parameter (Cijt) is modeled with an if–then cycle; in the spreadsheet, the formula “=IF(logical_test; value_if_true; value_if_false)” is employed, where the logical test is whether the work line is active or not. The true value (work line active) is the Cijt equation represented in Figure 2, and the false value (work line inactive) gives an extremely high penalty cost so that those cells are not considered and therefore are not assigned a production quantity. In the case of the required resource parameter for machine hours r1ij, the same logical test holds for the unit cost, where the true value is the equation of rkij shown in Figure 2 and the false value is 1.

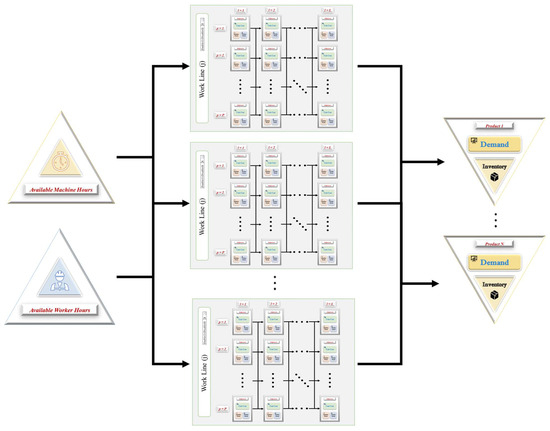

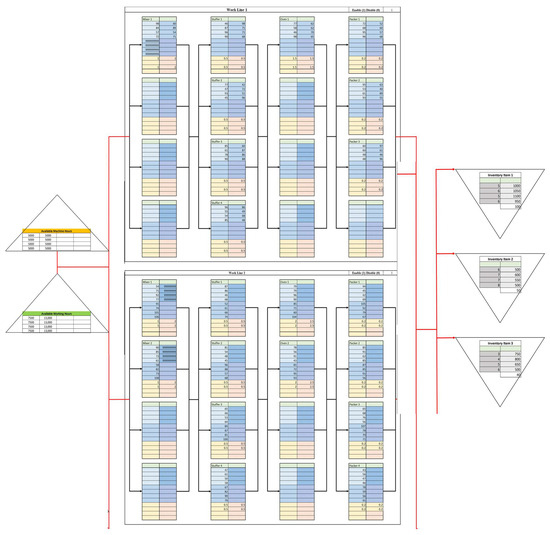

Figure 3 depicts the virtual icons of the methodology in the Initial Diagram. On the left are the available resources, in the center are the work lines, and on the right are the finished product inventories. Depending on the spatial configuration of the target production plant, the work lines are activated or deactivated and sub-processes used or not in series or parallel. Next, we will review in detail each of these virtual icons and how they work to build the model.

Figure 3.

Overview of the Initial Diagram.

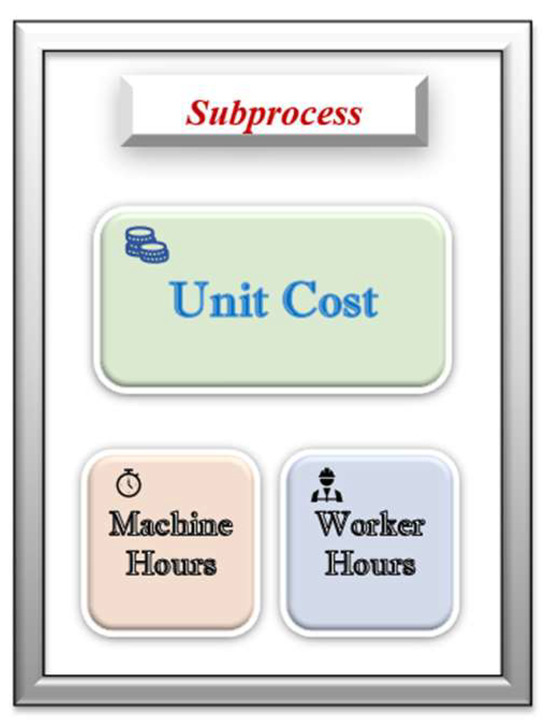

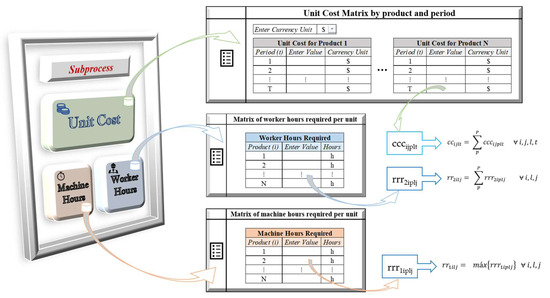

2.2.1. Sub-Processes Icon

The sub-process icon represents single machines, stages, or workstations that are part of a work line, as shown in Figure 4. The user must enter the parameters of the sub-process previously defined, in the matrices contained.

Figure 4.

Sub-process icon.

In the Initial Diagram, we can observe for each work line the sub-process icons placed in series and parallel configurations, as shown on the right side of Figure 5. If one or more sub-processes are not part of the target production system, it is acceptable to leave the editable data matrices of those icons blank. That is, the user will enter the required data only in the icons that represent machines, stages, or workstations effectively arranged in the plant layout.

Figure 5.

Editable sub-process icon arrays.

Three editable data matrices are embedded in each sub-process:

- Unit cost: matrix designed to enter the unit cost of production of the sub-process for the different products in the different planning periods;

- Machine hours: matrix designed to enter the machine hours required for one unit of the different products;

- Worker hours: matrix designed to enter the worker hours required for one unit of the different products.

Figure 5 shows the editable data matrices and the parameter of the mathematical model to which they correspond. As long as the number of products and the number of periods is lower than this limit capacity, the unused boxes remain blank, which applies to the three matrices.

Once the data per product and per period have been entered in the “EnterValue” column, the parameters will be automatically recognized in the model depending on the matrix:

- Unit cost will generate the parameter cccijplt;

- Machine hours will generate the parameter rrrkiplj with k = 1;

- Worker hours will generate the parameter rrrkiplj with k = 2.

The assignment of the parameter in the p and l index domain is automatically generated according to the position of the sub-process icon in the diagram.

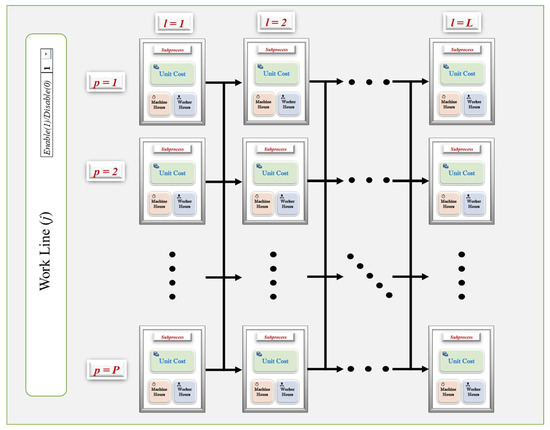

2.2.2. Work Line Icon

In the Initial Diagram, the user will observe work lines that contain the sub-process icons; if one or more sub-processes do not correspond to the target production system, it is sufficient to leave their data matrices blank. However, if one or more work lines do not correspond to the target production system, they must be deactivated with a button, as shown in Figure 6. Within each work line icon, each column of sub-process icons corresponds in the model to the index of sub-processes in series L, while each row corresponds in the model to the index of sub-processes in parallel P. On the other hand, activating a work line implies adding one more value to the index of the j-th work line. As shown in Figure 6, the sub-process icons are previously configured in all serial and parallel combinations, and it is enough to fill in the data matrices of those corresponding to the target production system to configure the work line.

Figure 6.

Work line icon.

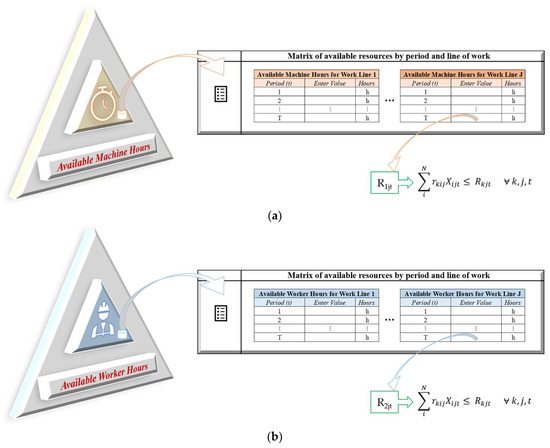

2.2.3. Available Resources Icons

In the Initial Diagram, we can observe, to the left of the work lines, the icons representing the available machine hours and worker hours resources as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Available resources icons.

In both cases, the user can edit a data matrix as shown in Figure 8. The resources available depend on the planning period and the work line.

Figure 8.

Editable matrices of available resources, (a) corresponds to the availability of machine hours and (b) to the availability of worker hours.

The matrix of available machine hours will generate the parameter Rkjt for k = 1, while the available worker hours matrix will generate the parameter Rkjt for k = 2 in the mathematical model.

The user must consider the calculation of available machine hours according to the time that the machines can effectively operate in each work line. When a stage has multiple sub-processes operating in parallel, the user must consider the time of the sub-process that takes the longest and not the algebraic sum of all of them, unlike the available worker hours that depend exclusively on the duration of the shift and the number of operators for each planning period.

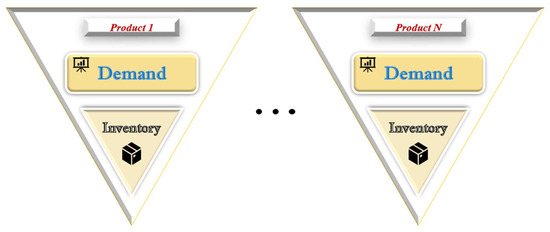

2.2.4. Demand and Available Inventory Icons

In the Initial Diagram, the user can observe, to the right of the work lines, the icons for demand and available inventory per product. If the diagram has more icons than necessary, it will be sufficient to leave the surplus demands at zero. Figure 9 shows the icons for N different products.

Figure 9.

Demand and inventory icons by product.

The demand matrix by product will generate the parameter Dit in the mathematical model, while the available inventory matrix must be activated with a button. If activated, the user can enter data such as the unit cost of inventory per period and the units available at the beginning, generating the parameters CIit and Ii0, respectively, in the mathematical model.

Figure 10 shows the editable matrices of the demand and inventory by product icon.

Figure 10.

Editable demand and inventory by product matrices.

Once all the target system data have been entered into the matrices, and once it has been defined which work lines need to be active, the optimal solution to the APP problem can be requested, resulting in the planning of the quantity and timing of production and inventory management over the desired planning horizon. The following section presents a case study to test the prototype based on the proposed methodology.

3. Prototype and Case Study: Sausage Products Factory

A theoretical case has been selected to test the tool. It should be noted that the prototype is in its initial stage; however, it is functional.

The prototype has been designed in Excel spreadsheets, and it currently has a capacity of four products, four planning periods, and four work lines, each with four serial sub-processes, where each serial sub-process has room for four parallel machines. The solution was obtained using the Excel OpenSolver add-in, and it has been tested on Windows 10 with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-10300H CPU @ 2.50 GHz, 2496 Mhz; four main processors; and eight logical processors.

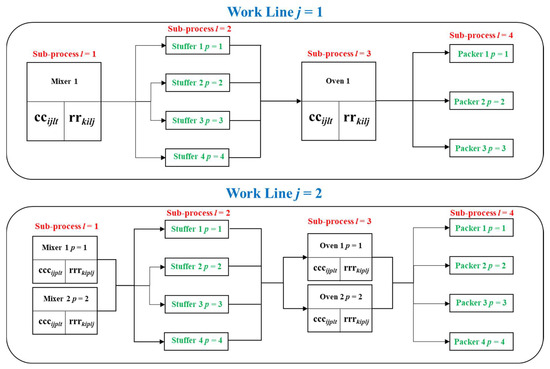

A flow shop case of a fictitious plant that produces three types of sausages in two working lines is proposed. The process starts with the sausage dough mixers, which supply parallel fillers to be precooked in industrial ovens and finally packaged in parallel packers.

Work line 1 has one mixer, four stuffers, one oven and three packers as shown in Figure 11, while work line 2 has two mixers, four stuffers, two ovens and four packers as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Flowchart for the proposed case study.

In addition, it should be considered that work line 1 can only process sausages 1 and 3, while work line 2 can only process sausages 1 and 2.

We assume that 100 finished units of sausage 1, 50 units of sausage 2, and 40 units of sausage 3 are currently available.

The forecasted demand for the next 4 weeks is 1000, 1050, 1100, and 950 units of sausage 1; 500, 600, 550, and 500 units of sausage 2; and 750, 800, 650, and 500 units of sausage 3, respectively.

Inventory unit costs and available capacities in hours per week and per line are shown in Table 3, for a 4-week planning horizon.

Table 3.

Availability in hours per line and inventory cost per product.

The unit production costs and the requirements for machine hours and worker hours per work line and per product are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Unit production costs per sausage, per line, per week.

In Appendix A are attached images of the case proposed in the prototype. To show the solution of this problem, APP should be considered in that, to activate a work line, the user must activate a manual switch in a cell of the icon of each line. In addition, obtaining a product to be produced on one line and not on another is achieved by penalizing with high costs.

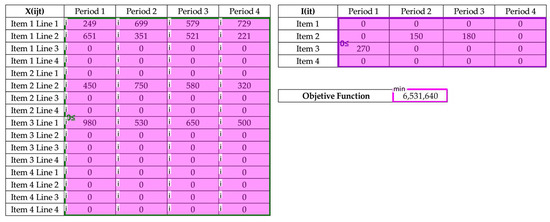

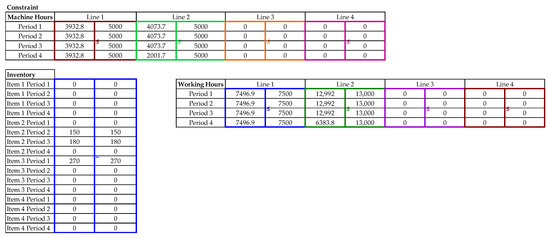

Figure 12 shows the optimal solution for the case of study in the prototype interface. The solution of the production variable can be observed on Xijt table, being the quantity of sausages to be produced for each line in each of the four weeks.

Figure 12.

Sausage case solution with the IBPlanner prototype.

The number of units of sausages to be stored in inventory each week is also shown, and the value of the total cost of the APP operation in this case is 6,531,640 currency units.

It is important to note that, although it is an initial prototype, in the solution spreadsheet, it is also possible to observe the slack in machine hours and worker hours. With this information, it is possible to make decisions, for example, to level the workforce or invest in machine capacity. The slack of the constraints in this case can be seen in Appendix B.

4. Discussion of Results

IBPlanner provides the solution to a classical APP problem, with the objective of minimizing the total cost associated with planning. It is noteworthy that there are currently numerous variations of this problem, and many authors have ventured into presenting multi-objective models with different approaches. Examples include Rasmi et al. (2019) [34] and Aydin et al. (2022) [8], who propose models incorporating sustainability aspects. Darvishi et al. (2020) [32] investigated APP in the textile industry under uncertainty conditions, while Jamalnia et al. (2019) [36] worked on comparing APP strategies under uncertainty conditions. Genetic algorithms have also been a focus of analysis in APP problems for researchers such as Goli et al. (2019) [1] and Yuliastuti et al. (2019) [37]. The fuzzy logic approach has been a recurrent focus for authors like Zaidan et al. (2019) [35] and Djordjevic et al. (2019), [40]. As authors, we align with their approaches in recognizing the need to diversify the possibilities of APP problems to have a broad range of methods that can adapt to the productive system we aim to enhance. The authors declare that this trend is necessary for the development of knowledge, and the complexity of associated mathematical modeling will continue to increase.

Therefore, the authors believe it is important to advance approaches that simplify the application of these advancements in productive industries; otherwise, it will be increasingly difficult for companies with little investment capacity to use these methodologies.

The authors agree with Jonsson and Ivert (2015) [44] that a company that plans its production with a tool, such as IBPlanner, obtains better and more feasible plans; we also disagree with Vlckova and Patak (2011) [45], who indicate that effective production planning can only be carried out through an integrated information system and not with spreadsheet-based methods, although this discrepancy lies in the fact that the prototype proposed by this research is not a conventional spreadsheet that applies a trial-and-error method but one that applies linear programming.

Although there are other examples of commercial production planning software, what makes IBPlanner unique is the reduction in resources that must be invested in to model the APP problem to meet an optimal solution. Starting from a process flow diagram or a plant layout, a user who is not necessarily a professional qualified to model mathematically a manufacturing situation can use the proposed conceptualization of icons to represent the elements of the production plant such as machines, work lines, or the resources involved.

Our approach is much more specific than software such as QAD, which offers a wide range of services and solutions for at least six different types of industries, or Solvoyo, that offers supply chain planning using artificial intelligence and machine learning. However, our methodology and tool are adapted to other types of needs and companies with a low level of investment and digital development, with few qualified personnel in operations management, such as SMEs. However, the potential of the proposed methodology can scale to be useful to any productive company, as, in agreement with Peter C. Bell (1988), interactive visual modeling benefits the development of operations research [52].

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a methodology based on icons was introduced for performing aggregate production planning without the need for the mathematical modeling inherent in linear programming problems. To apply this methodology, a software prototype named IBPlanner was presented. IBPlanner, based on Excel spreadsheets, is capable of solving multi-process and multi-product aggregate production planning problems with the objective of minimizing the total cost of production and inventory over a desired planning horizon. Based on the results from a case study, the authors conclude that this approach is particularly valuable for small and medium-sized enterprises or companies lacking qualified personnel for modeling or financial resources for research and development, although they must know the parameters and data of their production system.

The authors agree that the optimal solution of the case study is a good signal to implement the prototype in a real case and measure productive performance to test the hypothesis that IBPlanner improves productivity.

The authors anticipate that the use of the proposed tool will enhance company productivity. This tool offers a systematic approach to optimizing aggregate production planning, enabling companies to strategically plan production quantities for each product across various processes throughout predefined time periods. Additionally, the tool facilitates inventory planning by allowing companies to determine the optimal storage quantity per period, provided that storage space is available. Importantly, these benefits are achieved at a significantly lower total cost compared to current commercial programs in the market. This cost reduction is attributed to the tool’s user-friendly operation by company personnel and the straightforward nature of the prototype.

This conclusion holds both academic and managerial implications.

The icon-based methodology has the theoretical potential to be extended to more complex APP models, incorporating multiple objectives such as maximizing quality while minimizing costs (Galankashi et al. 2022, [18]). It could also be applied to models using genetic algorithms to address seasonal demands under uncertainty conditions (Goli et al. 2019, [1]), the optimization of renewable energy under uncertainty conditions (Islam et al. 2022, [15]), fuzzy programming (Sutthibutr et al. 2020), [31], or workforce leveling considerations (Jang et al. 2020, [33]). Exploring this potential would involve developing new icons to represent the desired implementations.

IBPlanner holds the potential to evolve into an integrated management tool for decision making. The authors conclude that its utility lies in the widespread accessibility of Excel within companies. However, being an initial prototype, the authors do not rule out the future possibility of programming it in another language to enhance its usability, interface, or modeling capabilities. Furthermore, the authors assert that IBPlanner can be adapted to solve other supply chain optimization problems, such as procurement, transportation, and distribution, as known linear programming models exist to address these issues. This conclusion motivates further research to make the icon-based methodology and IBPlanner a practical solution for integrated supply chain management while preserving the essence of simplifying modeling through icon usage.

The researchers conclude that the tool simplifies the intricacies of mathematical modeling in aggregate production plans. Designing a model that accurately represents the production plant typically demands a comprehensive understanding of linear programming. In this context, the tool offers the advantage of dispensing with the need for such specialized knowledge. Instead, users can operate the tool using editable virtual icons, simulating the target production system and deriving optimal aggregate production plans for a specified time horizon. This feature is particularly valuable for companies lacking the resources for extensive research and development in their production processes, with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) being the archetypal entities falling within this category. However, it is crucial to note that while the methodology streamlines the modeling process, it does not alleviate the complexities associated with data collection, classification, and simulation for decision making.

In conclusion, the authors hope that the use of this tool and methodology will contribute to the development of the global industrial manufacturing sector, with a particular emphasis on the Latin American region. Their aspiration is that it may foster economic and social growth in a region aspiring to compete with major world economies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D.; methodology, E.M.-M.; software, E.M.-M.; validation, E.M.-M. and J.M.S.; formal analysis, I.D.; investigation, I.D.; data curation, E.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.M.S.; visualization, J.M.S.; supervision, I.D. and J.M.S.; project administration, I.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Dicyt-USACH and Industrial Engineering Department of Universidad de Santiago de Chile.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Initial Diagram. Initial diagram viewed from the IBPlanner prototype in the case study.

Appendix B

Figure A2.

Constraints. Cells containing the constraints of the APP problem in the case study, where the slack of the resources machine hours and worker hours can be observed.

References

- Goli, A.; Tirkolaee, E.B.; Malmir, B.; Bian, G.-B.; Sangaiah, A.K. A multi-objetive invasive weed optimization algorithm for robust aggregate production planning under uncertain seasonal demand. Computing 2019, 101, 499–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzapour Al-e-hashem, S.M.J.; Baboli, A.; Sazvar, Z. A stochastic aggregate production planning model in a green supply chain: Considering flexible lead times, nonlinear purchase and shortage cost functions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 230, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Logendran, R. Aggregate production planning—A survey of models and methodologies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1992, 61, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, J. Setting manufacturing strategy for a factory-within-a-factory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 113, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilon, S. Five approaches to aggregate production planning. AIIE Trans. 1975, 7, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghalikhani, A.; Khoshalhan, F.; Mokhtari, H. Aggregate production planning: A literature review and future research directions. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2019, 10, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalnia, A.; Yang, J.-B.; Feili, A.; Xu, D.-L.; Jamali, G. Aggregate production planning under uncertainty: A comprehensive literature survey and future research directions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.S.; Tirkolaee, E.B. A systematic review of aggregate production planning literature with an outlook for sustainability and circularity. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, F. Special Issue “Scheduling: Algorithms and Applications”. Algorithms 2023, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elidrissi, A.; Benmansour, R.; Hasani, K.; Werner, F. Scheduling on parallel machines with a common server in charge of loading and unloading operations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16669. [Google Scholar]

- Yazd, S.; Salamirad, A.; Kheybari, S.; Ishizaka, A. An efficiency-based aggregate production planning model for multi-line manufacturing systems. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 2008–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özelkan, E.; Torabzadeh, S.; Demirel, E.; Lim, C. Bi-objective aggregate production planning for managing plan stability. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 178, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkolaee, E.B.; Aydin, N.S.; Mahdavi, I. A Hybrid Biobjective Markov Chain Based Optimization Model for Sustainable Aggregate Production Planning. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Rocha, J.E.; Hernandez-Gress, E.S. A Stochastic Programming Model for Multi-Product Aggregate Production Planning Using Valid Inequalities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.R.; Novoa, C.; Jin, T.D. Multi-facility aggregate production planning with prosumer microgrid: A two-stage stochastic program. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Kuthambalayan, T.S. Integrating operations and marketing decisions to manage perishability risks with target minimum remaining shelf-life available to consumers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, C.; Sola, A.V.H.; Matias, G.D.; Lermen, F.H.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Siqueira, H.V. Model for Integrating the Electricity Cost Consumption and Power Demand into Aggregate Production Planning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galankashi, M.R.; Madadi, N.; Helmi, S.A.; Rahim, A.A.; Rafiei, F.M. A Multiobjective Aggregate Production Planning Model for Lean Manufacturing: Insights from Three Case Studies. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.F.; Kao, H.C.; Chiang, F.Y.; Lin, S.W. Solving Aggregate Production Planning Problems: An Extended TOPSIS Approach. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.F.; Yang, X.F. A Multi-Objective Model and Algorithms of Aggregate Production Planning of Multi-Product with Early and Late Delivery. Algorithms 2022, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohale, V.; Ambilkar, P.; Gunasekaran, A.; Bilolikar, V. A multi-product and multi-period aggregate production plan: A case of automobile component manufacturing firm. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022, 29, 3396–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghin, R.G.; Darvishi, F. Integrated textile material and production management in a fuzzy environment: A logistics perspective. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 1380–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.F.; Yang, X.F. Multi-Objective Aggregate Production Planning for Multiple Products: A Local Search-Based Genetic Algorithm Optimization Approach. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2021, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, J.; Alinezhad, A. Performance evaluation in aggregate production planning using integrated RED-SWARA method under uncertain condition. Sci. Iran. 2021, 28, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuang, D.H.; Chiadamrong, N. A Fuzzy Credibility-Based Chance-Constrained Optimization Model for Multiple-Objective Aggregate Production Planning in a Supply Chain under an Uncertain Environment. Eng. J. 2021, 25, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U.; Ahmad, A.; Ali, Z.; Baig, S.A.; Manzoor, U. Optimization of Aggregate Production Planning Problems with and without Productivity Loss using Python Pulp Package. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2021, 12, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Krajcovic, M.; Furmannova, B.; Grznar, P.; Furmann, R.; Plinta, D.; Svitek, R.; Antoniuk, I. System of Parametric Modelling and Assessing the Production Staff Utilization as a Basis for Aggregate Production Planning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.F.; Pang, N.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.M. An Uncertain APP Model with Allowed Stockout and Service Level Constraint for Vegetables. Symmetry 2021, 13, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, D.; Zandi, A.; Behdad, S.; Entezaminia, A. A light robust model for aggregate production planning with consideration of environmental impacts of machines. Oper. Res. 2021, 21, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabzadeh, S.; Ozelkan, E.C. Fuzzy aggregate production planning with flexible requirement profile for plan stability in uncertain environments. Eur. J. Ind. Eng. 2021, 15, 514–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthibutr, N.; Chiadamrong, N. Integrated Possibilistic Linear Programming with Beta-Skewness Degree for a Fuzzy Multi-Objective Aggregate Production Planning Problem under Uncertain Environments. Fuzzy Inf. Eng. 2020, 12, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, F.; Yaghin, R.G.; Sadeghi, A. Integrated fabric procurement and multi-site apparel production planning with cross-docking: A hybrid fuzzy-robust stochastic programming approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 92, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Chung, B.D. Aggregate production planning considering implementation error: A robust optimization approach using bi-level particle swarm optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 142, 106367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, S.A.B.; Kazan, C.; Turkay, M. A multi-criteria decision analysis to include environmental, social, and cultural issues in the sustainable aggregate production plans. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 132, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, A.A.; Atiya, B.; Abu Bakar, M.R.; Zaidan, B.B. A new hybrid algorithm of simulated annealing and simplex downhill for solving multiple-objective aggregate production planning on fuzzy environment. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalnia, A.; Yang, J.B.; Xu, D.L.; Feili, A.; Jamali, G. Evaluating the performance of aggregate production planning strategies under uncertainty in soft drink industry. J. Manuf. Syst. 2019, 50, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliastuti, G.E.; Rizki, A.M.; Mahmudy, W.F.; Tama, I.P. Optimization of Multi-Product Aggregate Production Planning Using Hybrid Simulated Annealing and Adaptive Genetic Algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2019, 10, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazami, A.A.; Saidi-Mehrabad, M. Bender’s decomposition algorithm for robust aggregate production planning considering pricing decisions in competitive environment: A case study. Sci. Iran. 2019, 26, 3007–3031. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y.F.; Pang, N.; Wang, X. An Uncertain Aggregate Production Planning Model Considering Investment in Vegetable Preservation Technology. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8505868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, I.; Petrovic, D.; Stojic, G. A fuzzy linear programming model for aggregated production planning (APP) in the automotive industry. Comput. Ind. 2019, 110, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penlesky, R.; Srivastava, R. Aggregate production planning using spreadsheet software. Prod. Plan. Control 2007, 5, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Keegan, J.; Vigus, B.; Wood, K. The Kellogg company optimizes production, inventory, and distribution. Interfaces 2001, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, C.F.; Mesquita, M.A. Advanced planning systems (APS) for supply chain planning: A case study in dairy industry. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2015, 12, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, P.; Ivert, L.K. Improving performance with sophisticated master production scheduling. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 168, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlckova, V.; Patak, M. Barriers of demand planning implementation. Econ. Manag. 2011, 1, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Dini, M.; Stumpo, G. Mipymes en América Latina: Un Frágil Desempeño y Nuevos Desafíos Para las Políticas de Fomento; Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2018/75/Rev.1); Comisión Económica Para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Conference Board. Total Economy Database. 2020. Available online: https://conference-board.org/data/economydatabase (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- OIT (Organización Internacional del Trabajo). ILOSTAT. 2020. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/es/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Grosman, N.; Braude, H.; Rovira, S.; Patiño, A. Hecho en América Latina: Fabricación Inteligente y Una Nueva Esperanza de Industrialización en la Región; Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2021/111); Comisión Económica Para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.ingenieros.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Especialidad-INDUSTRIAL1.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Available online: https://blogs.unitec.mx/vida-universitaria/la-unitec/mexico-necesita-ingenieros/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Bell, P.C. Visual interactive modelling: The past, the present, and the prospects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1988, 54, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).