Abstract

Conjugate gradient methods are widely used and attractive for large-scale unconstrained smooth optimization problems, with simple computation, low memory requirements, and interesting theoretical information on the features of curvature. Based on the strongly convergent property of the Dai–Yuan method and attractive numerical performance of the Hestenes–Stiefel method, a new hybrid descent conjugate gradient method is proposed in this paper. The proposed method satisfies the sufficient descent property independent of the accuracy of the line search strategies. Under the standard conditions, the trust region property and the global convergence are established, respectively. Numerical results of 61 problems with 9 large-scale dimensions and 46 ill-conditioned matrix problems reveal that the proposed method is more effective, robust, and reliable than the other methods. Additionally, the hybrid method also demonstrates reliable results for some image restoration problems.

Keywords:

hybrid conjugate gradient method; acceleration scheme; sufficient descent property; global convergence; ill-conditioned matrix; image restoration MSC:

65K05; 90C26

1. Introduction

In this paper, we consider the following unconstrained problem:

where is continuously differentiable, bound below, and its gradient is available. There are many effective methods for problem (1), such as Newton-type methods, quasi-Newton-type methods, spectral gradient methods, and conjugate gradient (CG for abbreviation) methods [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], etc. Meanwhile, there are also various free gradient optimization tools such as Nelder–Mead, generalized simulated annealing, and genetic algorithm [12,13,14], etc., for problem (1). In this part, we focus on CG methods and propose a new hybrid CG method for a large-scale problem (1). Actually, CG methods are one of the most effective methods for unconstrained problems, especially for large-scale cases, due to their low storage and globally convergent properties [3], in which the iterative point is usually generated by

where is the current iteration; the scalar is the step length, determined by some line search strategy; and is the search direction, defined by

where and is called the conjugate parameter. A number of CG methods have been proposed by various modifications of the direction and the parameter ; see [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,15,16,17,18,19,20], etc. Some CG methods have strong convergence properties, but their numerical performances may not be good in practice due to the jamming phenomenon [4]. These methods include Fletcher–Reeves (FR) [5], Dai–Yuan (DY) [6], and Fletcher (CD) [7], with the following conjugate parameters:

where , , and stands for the Euclidean norm. On the other hand, some other CG methods may perform well in practice, but their convergence may be not guaranteed, especially for nonconvex functions. These methods include Hestenes–Stiefel (HS) [8], Polak–Ribière–Polyak (PRP) [9,10], and Liu–Storey (LS) [11], with the following conjugate parameters:

In fact, these methods possess an automatically approximate restart feature which can avoid the jamming phenomenon, that is, when the step is small, the factor tends to zero, resulting in the conjugate parameter becoming small and the new direction approximating to the steepest descent direction .

To attain good computational performance and maintain the attractive feature of strong global convergence, many scholars have paid special attention to hybridizing these CG methods. Specifically, the authors in [21] proposed a hybrid PRP-FR CG method (H1 method in [22]) and the corresponding conjugate parameter was defined as . Moreover, based on the above hybrid conjugate parameter, a new form was proposed in [23], where the parameter was defined by , and the global convergence property was established for the general function without the convexity assumption. In [24], a hybrid of the HS method and DY method was proposed in which the conjugate parameter was defined by The numerical results indicated that the above hybrid method was more effective than the PRP algorithm. In the above hybrid CG methods, the search direction was in the form of (3). Moreover, the authors in [25] proposed a new hybrid three-term method in which the conjugate parameter is and the direction is where is the convex parameter. The above hybrid method demonstrates attractive numerical performance. Furthermore, in [22], the authors proposed two new hybrid methods based on the above conjugate parameters with different search directions. Concretely, the directions have the following common form:

where or . A remarkable feature of the above directions is that the sufficient descent property is automatically satisfied, independent of the accuracy of the line search strategy.

Motivated by the above discussions, in this paper, we propose a new hybrid descent CG method for large-scale nonconvex problems. The proposed hybrid method automatically enjoys the sufficient descent property independent of the accuracy of the line search technique. Furthermore, the global convergence for the general functions without convexity is established under the standard conditions. Numerical results of 549 large-scale problems and 46 ill-conditioned matrix problems indicate the proposed method is attractive and promising. Finally, we also apply the proposed method to some image restoration problems, which also verifies its reliability and effectiveness.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we propose a descent hybrid CG method which is based on the MHS method and DY method. Moreover, the sufficient descent property is satisfied independent of the accuracy of the line search techniques. Global convergence is established for the general function in Section 3. Numerical results are given in Section 4 to indicate the effectiveness and reliability of the proposed algorithm. Finally, some conclusions are presented.

2. Motivation, Algorithm, and Sufficient Descent Property

As mentioned in the above section, the HS method is generally regarded as one of the most effective CG methods, but its global convergence for general nonlinear functions is still erratic. Additionally, the HS method does not guarantee the descent property during the iterative process, that is, the condition may not be satisfied for . Therefore, many researchers have been devoted to designing some descent HS conjugate gradient methods [4,24,26,27,28,29,30], etc. Specifically, to obtain an intuitively modified conjugate parameter, the authors in [26] approximated the direction by the two-term direction (3), where was defined by (4) with . Concretely, the least squares problem was solved. After some algebraic manipulations, the unique solution was

where

The above parameter and its modifications have some nice theoretical properties [26] and the method with (5) and (3) performs well. Meanwhile, it is clear that if the exact line search is adopted (i.e., ), it holds that .

To attain attractive computational performance and good theoretical properties, many researchers have proposed hybrid CG methods. Among these methods, hybridizations of the HS method and the DY method have shown promising numerical performance [31,32,33,34], etc. The HS method has a nice property of automatically satisfying the conjugate condition for independent of the accuracy of the line search strategies and the convexity of the objective function and performs well in practice. On the other hand, the DY method has remarkable convergence properties. These characteristics motivate us to propose new hybridizations of the HS method and the DY method which not only have attractive theoretical properties but also better numerical performance for large-scale nonconvex problems.

In the following, we focus on the conjugate parameter and propose a new hybrid conjugate parameter of and :

Now, based on the new hybrid conjugate parameter and the modified descent direction (8), we propose our hybrid algorithm (NMHSDY) in detail.

It should be noted that the line search technique in Algorithm 1 is not fixed: It can be selected by the users. Next, we show that the search direction generated by Algorithm 1 automatically has a sufficient descent property independent of any line search strategy.

| Algorithm 1 New descent hybrid algorithm of MHS and DY methods (NMHSDY) for nonconvex functions. |

Step 0. Input and Initialization. Select an initial point , parameter and compute and . Set and ; Step 1. If , then stop; Step 2. Compute step length along direction by some line search strategy; Step 3. Let ; Step 4. Compute the conjugate parameter by (7) and the search direction by

Step 5. Set and go to Step 2. |

Theorem 1.

Let the search direction be defined by (8) in Algorithm 1. Then, for any line search strategy, the sufficient descent property holds for nonconvex function , that is,

3. Convergence for General Nonlinear Functions

In this section, the global convergence of the NMHSDY method is presented. Before that, some common assumptions are listed.

Assumption 1.

The level set is bounded, where is the initial point, i.e., there exists a positive constant such that

Assumption 2.

In some neighborhood of , the gradient is Lipschitz continuous, i.e., there exists a constant such that

Based on the above assumptions, we further obtain that there exists a constant such that

In fact, it holds that ; hence, M can be or larger than that.

The line search strategy is another important element in iterative methods. In this part, we take the standard Wolfe line search strategy:

where . By property (9) and line search (13), it is satisfied that

that is, the sequence is non-increasing and the sequence generated by Algorithm 1 is contained in the level set . Since f is continuously differentiable and the set is bounded, then there exists a constant such that

The Zoutendijk condition [35] plays an essential role in the global convergence of nonlinear CG methods. For completeness, we here state the lemma but omit its proof.

Lemma 1.

Suppose that Assumptions 1 and 2 hold. Consider any nonlinear CG method, in which is obtained by the standard Wolfe line search (13) and is a descent direction (). Then, we have

Thereafter, the convergence property is presented in the following theorem for the general functions without convexity assumption.

Theorem 2.

Let Assumptions 1 and 2 hold and the sequence be generated by the NMHSDY algorithm. Set , and if holds, then we have

Proof.

We now prove (15) by contradiction and assume that there exists a constant such that

Let be , then the direction (8) can be rewritten as

After some algebraic manipulation, we have

Dividing both sides of the above equality by , from (9), we have

where the first inequality holds by and the last inequality holds by the bound for the scale . By (17) and , it holds that

Then, by the above inequality and (16), it follows that

which indicates that

which contradicts the Zoutendijk condition (14). So, (15) holds. □

Remark 1.

In [24], the authors presented a class of hybrid conjugate parameters, one of which is , with the corresponding interval for being . It is reasonable that the interval in our paper is smaller since we take instead of and .

In the following, we discuss the global convergence of Algorithm 1 for general nonlinear functions in the case of . Motivated by the modified secant conditions in [36,37], in this part, based on the Wolfe line search strategy (13), we consider the following settings:

where is a constant. With the above setting, the modified conjugate parameter becomes

where and are, respectively,

Meanwhile, the corresponding direction turns to

The following lemma indicates the property of the scalar and .

Proof.

In the following, we assume that Algorithm 1 never stops and there exists a constant such that for all k, (16) holds.

Lemma 3.

Proof.

Based on the Wolfe line search technique (13), it holds that

where the first inequality holds by the non-negativity of and the last inequality holds by the sufficient descent property (9). Meanwhile, by (9) and the Cauchy–Schwartz inequality, it holds that, for ,

which implies that from condition (16),

By the definition of , we obtain that

where the second inequality holds by (21), the third inequality holds by (22), the fourth inequality holds by the condition for all , the fifth inequality holds by (25), and the last inequality holds by the condition (16). Furthermore, we have

By the definition of in (20) and the above discussions, it holds that

With the help of (25), we conclude that

Hence, (23) holds. This completes the proof. □

Theorem 3.

Proof.

We prove the conclusion by contradiction and assume that there exists a positive constant such that (16) holds. Otherwise, Algorithm 1 converges in the sense of (15). From (9), we conclude that the new direction enjoys the sufficient descent property. Therefore, Lemma 1 holds, which implies that

where the first inequality holds by (16), the second inequality holds by (9) and (23), and the last inequality holds by Lemma 1. However, that is a contradiction and the assumption does not hold. So, the holds. This completes the proof. □

4. Numerical Performance

In this section, we focus on the numerical performance of Algorithm 1 and compare it with several effective CG methods. In the experiment, we code these algorithms in Matlab 2016b and perform them on a PC computer, whose processor has AMD 2.10 GHz, RAM of 16.00 GB and the Windows 10 operating system.

4.1. Performance on Benchmark Problems

In this subsection, we check the performance of the NMHSDY method and compare it with two effective modified HS methods in [26,28] and the hybrid method in [24]. In [26], the authors proposed an effective modified HS method (MHSCG method for abbreviation) in which the conjugate parameter is

where is a parameter. The direction in [26] is in the form of (3) and the corresponding method has attractive numerical performance. Dai and Kou in [28] introduced another effective class of CG schemes (DK+ method for abbreviation) depending on the parameter , where the corresponding conjugate parameter is defined by

The direction in [28] is also in the form of (3). To establish global convergence for general nonlinear functions, a truncated strategy is used, that is,

where is a parameter. The numerical results indicated the DK+ method has good and reliable numerical performance. Dai and Yuan, in [24], proposed an effective hybrid CG method (HSDY method for abbreviation) in which the conjugate parameter is

The hybrid method also has global convergence and attractive numerical performance.

In the following, we focus on the numerical performance and the large-scale unconstrained problems in Table 1 (see [38] for details). In order to improve numerical performance, Andrei, in [39], proposed an accelerated strategy which modified the step in a multiplicative manner. In this part, we also utilize this strategy and regard Algorithm 1 with the accelerated strategy as Algorithm 1. To compare the conjugate parameters and the search directions fairly, here we adopt the Wolfe line search technique (13) for all methods.

Table 1.

The test problems.

In the experiment, for each problem we consider nine large-scale dimensions with 300, 600, 900, 3000, 6000, 9000, 30,000, 60,000 and 90,000 variables. The parameters used in the Wolfe line search are and . The other parameters for the MHSCG method and the DK+ method are as default.

During the progress, the Himmeblau stopping rule is adopted: if , let , otherwise, . If the conditions or are satisfied, then the progress is stopped, where the values of parameters , , and are , and . Meanwhile, we also stop the algorithm when the number of iterations is greater than 5000.

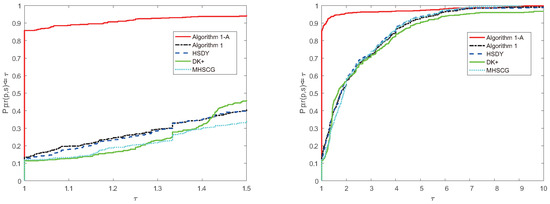

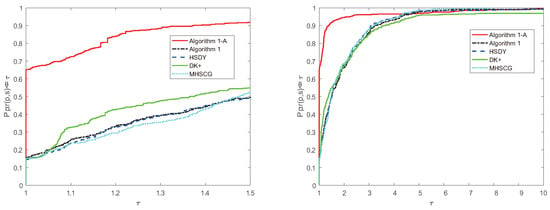

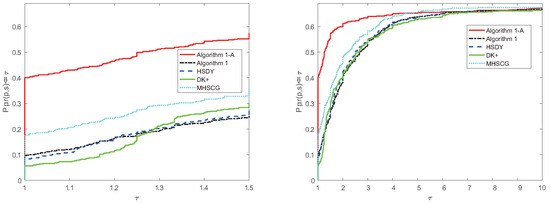

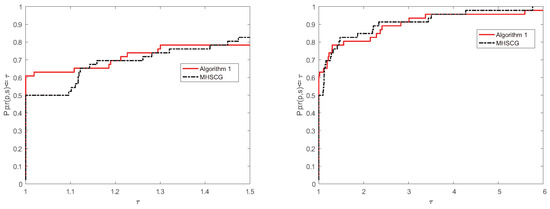

In order to present the performances of methods more intuitively, the tool in [40] is adopted to analyze the profiles of these methods. Robustness and efficiency rates are readable on the right and left vertical axes of the corresponding performance profiles, respectively. To present a detailed numerical comparison, two different scales have been considered for the -axis. One is , which shows what happens for the values of near to 1. The other is used to present the trend for large values of . In Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, we, respectively, show the performance of these methods relative to the number of iterations (), the number of function-gradient valuations (; which is the sum of the number of function valuations and gradient valuations), and the CPU time consumed in seconds.

Figure 1.

Performance profiles of the methods in the number of iterations case.

Figure 2.

Performance profiles of the methods in the function and gradient case.

Figure 3.

Performance profiles of the methods in the CPU time consumed case.

From Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, we have that Algorithm 1 is comparable and a little more effective than the HSDY method, the DK+ method, and the MHSCG method for the above problems. Meanwhile, Algorithm 1, with the accelerated strategy, is much effective and performs best in the experiment, which indicates that the accelerated technique indeed works and reduces the number of iterations and the number of function and gradient evaluations.

4.2. Comparison for Stability

In this subsection, we consider the numerical stability of Algorithm 1 for the ill-conditioned matrix problems and compare it with the MHSCG method in [26]. In fact, the quadratic objective function of (1) is ill-conditioned if matrix is in the form

It is clear that the matrix is ill-conditioned and positive definite [41], with different dimensions . Furthermore, the authors in [42] show that the norm condition number of the Hessian matrix gradually increases from for to for . In the following, we explore the numerical performance. The experimental environment, the parameter values, and the stop rule remain the same as in the above subsection. Meanwhile, the initial point is selected as . The corresponding numerical results are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, in which is the dimension of x, means the number of iterations, is the sum of the number of function and gradient evaluations, means the CPU time consumed in seconds, and denotes the optimal function obtained by the methods.

Table 2.

Numerical results of the MHSCG method and Algorithm 1 in 5–40 dimensions.

Table 3.

Numerical results of the MHSCG method and Algorithm 1 in 41–50 dimensions.

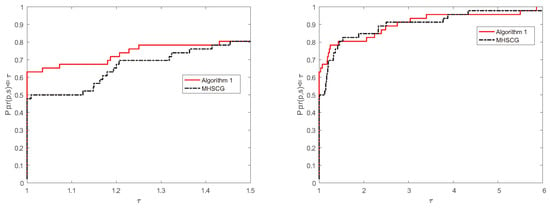

From Table 2 and Table 3, it can be found that for the dimensions from 5 to 50, Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method successfully solve all of them and obtain reasonable optimal function values, which are all not greater than . For most problems, Algorithm 1 needed fewer iterations and function and gradient evaluations and obtained better optimal values. In order to show numerical performance intuitively, here we also adopt the performance profiles in [40] for the NI and NFG cases. The corresponding performance profiles are given in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Performance profiles of Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method in NI case.

Figure 5.

Performance profiles of Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method in NFG case.

Figure 4 shows that Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method solve these testing problems with the least total number of iterations in 63% and 48% of cases, respectively. Figure 5 indicates that Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method solve these testing problems with the least total number of function and gradient evaluations in 61% and 50% of cases, respectively. All in all, the numerical results show that Algorithm 1 is more effective and stable than the MHSCG method for these ill-conditioned matrix problems.

4.3. Application to Image Restoration

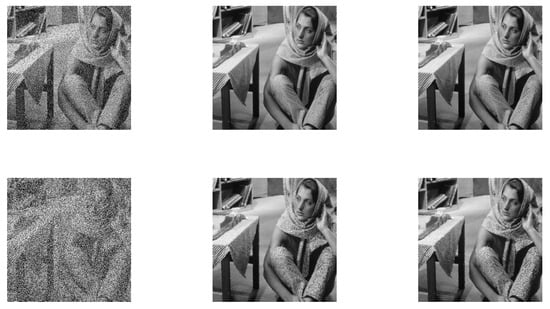

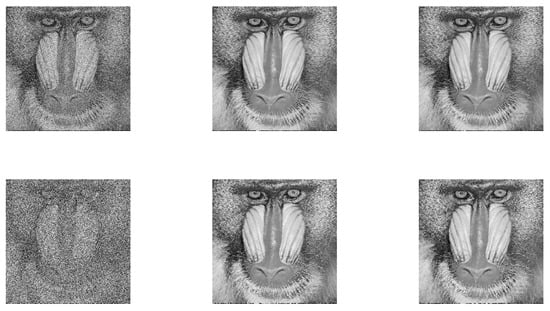

In this subsection, we apply Algorithm 1 to some image restoration problems [43,44,45]. During the process, the normal Wolfe line search technique is adopted, the corresponding parameters remain unchanged, and two noise level cases for the Barbara.png () and Baboon.bmp () images are considered. In this part, we stop the process when the following criteria are both satisfied:

Meanwhile, to assess the restoration performance qualitatively, we also utilize the peak signal to noise ratio [45] (PSNR), which is defined by where M and N are the true image pixels, and and denote the pixel values of the restored image and the original image, respectively. For the noise level, we consider two cases: (a low-level case) and (a high-level case). The consumed CPU time and the corresponding PSNR values are given in Table 4. Meanwhile, the detailed performances are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively.

Table 4.

Test results for Algorithm 1 and the MHSCG method.

Figure 6.

The noisy Barbara image, corrupted by salt-and pepper noise (the first column); the images restored via Algorithm 1 (the second column), and via the MHSCG method (the third column).

Figure 7.

The noisy Baboon image, corrupted by salt-and pepper noise (the first column); the images restored via Algorithm 1 (the second column), and via the MHSCG method (the third column).

5. Conclusions

Conjugate gradient methods are attractive and effective for large-scale unconstrained optimization smooth problems due to their simple computation and low memory requirements. The Dai–Yuan conjugate gradient method has good theoretical properties and generates a descent direction in each iteration. Whereas, the Hestenes–Stiefel conjugate gradient method automatically satisfies the conjugate condition without any line search technique and performs well in practice. By the above discussions, we propose a new descent hybrid conjugate gradient method. The proposed method has a sufficient descent property independent of any line search technique. Under some mild conditions, the proposed method is globally convergent. In the experiments, we first consider 61 unconstrained problems with 9 different dimensions up to . Thereafter, 46 ill-conditioned matrix problems are also tested. The primary numerical results show that the proposed method is more effective and stable. Finally, we apply the hybrid method to some image restoration problems. The results indicate our method is attractive and reliable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., X.W., Y.T. and L.P.; methodology, S.W. and X.W.; software, X.W.; validation, X.W., L.P. and Y.T.; formal analysis, X.W., Y.T. and L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Science Foundation of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (ZSTU) under Grant No. 21062347-Y.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Li, D.; Fukushima, M. A global and superlinear convergent Gauss-Newton-based BFGS method for symmetric nonlinear equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1999, 37, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Z. Gradient trust region algorithm with limited memory BFGS update for nonsmooth convex minimization. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2013, 54, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, D.; Yin, H.; Yuan, Y. Convergence properties of nonlinear conjugate gradient methods. SIAM J. Optim. 2000, 10, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, W.; Zhang, H. A new conjugate gradient method with guaranteed descent and an efficient line search. SIAM J. Optim. 2005, 16, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.; Reeves, C.M. Function minimization by conjugate gradients. Comput. J. 1964, 7, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yuan, Y. A nonlinear conjugate gradient method with a strong global convergence property. SIAM J. Optim. 1999, 10, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Practical Methods of Optimization; Unconstrained Optimization; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, UAS, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hestenes, R.; Stiefel, L. Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1952, 49, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, B.T. The conjugate gradient method in extreme problems. USSR Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 1969, 9, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, E.; Ribière, G. Note sur la convergence de méthodes de directions conjuguées. Rev. Fr. Informat Rech. Opér. 1969, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Storey, C. Efficient generalized conjugate gradient algorithms Part 1: Theory. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1991, 69, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Gong, X.G. Efficiency of generalized simulated annealing. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 62, 4473–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Q.; Qian, F. A hybrid genetic algorithm for twice continuously differentiable NLP problems. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2010, 34, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.C.; Han, L.X. Implementing the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm with adaptive parameters. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2012, 51, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Wang, X.; Sheng, Z. The projection technique for two open problems of unconstrained optimization problems. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2020, 186, 590–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Wang, X.; Sheng, Z. Family weak conjugate gradient algorithms and their convergence analysis for nonconvex functions. Numer. Algorithms 2020, 84, 935–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, A.; Esmaeilpour, M.; Sheikhahmadi, A. A new family of Polak-Ribière-Polyak conjugate gradient method for impulse noise removal. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 17515–17524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, B.T. Introduction to Optimization; Optimization Software Inc., Publications Division: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, G.; Pang, L. A class of new three-term descent conjugate gradient algorithms for large-scale unconstrained optimization and applications to image restoration problems. Numer. Algorithms 2023, 93, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. A class of spectral three-term descent Hestenes-Stiefel conjugate gradient algorithms for large-scale unconstrained optimization and image restoration problems. Appl. Numer. Math. 2023, 192, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati-Ahmed, D.; Storey, C. Efficient hybrid conjugate gradient techniques. J. Optim.Theory Appl. 1990, 64, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, W. Two descent hybrid conjugate gradient methods for optimization. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2008, 216, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.; Nocedal, J. Global convergence properties of conjugate gradient methods for optimization. SIAM J. Optim. 1992, 2, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yuan, Y. An efficient hybrid conjugate gradient method for unconstrained optimization. Ann. Oper. Res. 2001, 103, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liao, W.; Yin, J.; Jian, J. A new family of hybrid three-term conjugate gradient methods with applications in image restoration. Numer. Algorithms 2022, 91, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, K.; Faramarzi, P.; Pirfalah, N. A modified Hestenes-Stiefel conjugate gradient method with an optimal property. Optim. Methods Softw. 2019, 34, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narushima, Y.; Yabe, H.; Ford, J. A three-term conjugate gradient method with sufficient descent property for unconstrained optimization. SIAM J. Optim. 2011, 21, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Kou, C. A nonlinear conjugate gradient algorithm with an optimal property and an improved Wolfe line search. SIAM J. Optim. 2013, 23, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldu, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yemane, H. A modified nonlinear conjugate gradient algorithm for large-scale nonsmooth convex optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2020, 185, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y. A modified Hestenes and Stiefel conjugate gradient algorithm for large-scale nonsmooth minimizations and nonlinear equations. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2016, 168, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaie-Kafaki, S.; Fatemi, M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. Two effective hybrid conjugate gradient algorithms based on modified BFGS updates. Numer. Algorithms 2011, 58, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livieris, I.; Tampakas, V.; Pintelas, P. A descent hybrid conjugate gradient method based on the memoryless BFGS update. Numer. Algorithms 2018, 79, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshgam, Z.; Ashrafi, A. A new hybrid conjugate gradient method for large-scale unconstrained optimization problem with non-convex objective function. Comp. Appl. Math. 2019, 38, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Kaelo, P. A linear hybridization of Dai-Yuan and Hestenes-Stiefel conjugate gradient method for unconstrained optimization. Numer.-Math.-Theory Methods Appl. 2021, 14, 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Zoutendijk, G. Nonlinear Programming, Computational Methods; Integer & Nonlinear Programming: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970; pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Fukushima, M. A modified BFGS method and its global convergence in nonconvex minimization. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2001, 129, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaie-Kafaki, S.; Ghanbari, R. A modified scaled conjugate gradient method with global convergence for nonconvex functions. B Bull. Belg. Math. Soc. Simon Stevin 2014, 21, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, N. An unconstrained optimization test functions collection. Environ. Ence Technol. 2008, 10, 6552–6558. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, N. An acceleration of gradient descent algorithm with backtracking for unconstrained optimization. Numer. Algorithms 2006, 42, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.; Moré, J. Benchmarking optimization software with performance profiles. Math. Program 2002, 91, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S. Fundamentals of Matrix Computations; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Babaie-Kafaki, S. A hybrid scaling parameter for the scaled memoryless BFGS method based on the ℓ∞ matrix norm. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2019, 96, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y. A descent spectral conjugate gradient method for impulse noise removal. Appl. Math. Lett. 2010, 23, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z. The PRP conjugate gradient algorithm with a modified WWP line search and its application in the image restoration problems. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 152, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovik, A. Handbook of Image and Video Processing; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).