1. Introduction

A network is typically depicted using an undirected simple graph, where nodes represent vertices and the connections between them are represented by edges. The central aspect of network analysis involves identifying which nodes hold significant positions within the network. Graph theory has become one of the most powerful mathematical tools in network analysis, offering numerous techniques and methodologies. One of the most important tasks of network analysis is to determine which nodes or links are more critical in a network. One such parameter, closeness, serves as a means of identifying nodes capable of efficiently disseminating information throughout the network. In simpler terms, a node with high closeness is one that can reach other nodes in the network quickly and efficiently. It signifies that the node is closely connected to the rest of the network and can potentially influence or be influenced by other nodes more rapidly than nodes with lower closeness values. Nodes with high closeness are crucial in various network applications, such as communication networks, social networks, and transportation networks, as they can facilitate rapid information flow, influence decision-making processes, and enhance overall network resilience. Thus, understanding the closeness of nodes provides valuable insights into the structural and functional characteristics of complex networks.

Closeness is measured on a scale from 0 to 1. A node with a value nearing 0 suggests it is relatively distant from other nodes within the network. Consequently, reaching other nodes from this point necessitates traversing numerous links. Conversely, a node with a value approaching 1 indicates it is in close proximity to other nodes. As a result, only a few connections are needed to reach neighbouring nodes from this node within the network.

Freeman first introduced the concept of closeness [

1], but it turned out to be ineffective for disconnected graphs and exhibited weaknesses during graph operations. Addressing the first limitation, Latora and Marchiori introduced a novel measure of closeness for disconnected graphs [

2], yet it still remains susceptible to the second weakness. Subsequently, Danglachev proposed an alternative definition [

3], which effectively addresses the challenges posed by disconnected graphs and facilitates the creation of convenient formulas for graph operations. Following this definition of closeness, various vulnerability measures have been formulated to quantify the resilience of a network. Among these novel measures are the vertex (or edge) residual closeness parameters, which assess the closeness of a graph following the removal of vertices (or edges) [

3]. Another measure is the additional closeness, which identifies the maximum potential of the closeness of a network, by means of the addition of a connection [

4,

5]. For further information on these new finer parameters, we recommend referring to [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The computation of closeness across various classes of graphs has gained significant attention in recent years [

3,

13,

14,

15]. For instance, Danglachev investigated the closeness of splitting graphs [

16]. In [

17], the same author determined the closeness of line graphs for certain fundamental graphs, as well as the closeness of line graphs connected by a bridge of two basic graphs. Closeness formulas for various graph classes were derived by Golpek [

18]. Poklukar and Žerovnik [

19] identified the graphs that minimize and maximize closeness among all connected graphs and trees with a fixed order, respectively. They also determined the graphs that uniquely maximize closeness among all cacti of fixed order and number of cycles, posing an open problem for the minimum case. The open problem posed by Poklukar and Žerovnik [

19] was solved by Hayat and Xu [

20], which obtained the unique graph that minimizes closeness across all cacti with fixed numbers of vertices and cycles. The notion of closeness in spectral graph theory was recently combined by Zheng and Zhou [

21]. They also investigated the closeness matrix and established the connection between the closeness eigenvalues and the graph structure.

Basic Notations and Definitions

Let G be a simple connected graph with vertex set and edge set . For a vertex , refers to the set of vertices adjacent to v in G. The degree of a vertex , denoted by , is the number of vertices in . A pendent vertex in a graph is a vertex with degree one and an edge incident to a pendent vertex is called a pendent edge. For an edge , denotes the subgraph of G obtained by removing e, and represents a graph formed from G by adding an edge between x and y, where . Deleting a vertex (along with its incident edges) from G is denoted by . The union of two graphs and , denoted by is the graph with and . The join of two graphs and , denoted by is a graph obtained from and by joining each vertex of to all vertices of . For disjoint graphs with , the sequential join is the graph obtained from by joining each vertex of to all vertices of and then joining each vertex of to all vertices of , and continuing in this manner, finally connecting each vertex of to all vertices of . For simplicity, (and ) is used to represent the union (and sequential join) of t disjoint copies of G. For example which is the t isolated vertices and is the sequential join .

A matching in G is a set of edges that do not have a set of common vertices. A perfect matching in G is a matching that covers each vertex of G.

For vertices , the distance between u and v in G is the length of the shortest path connecting them, and denoted by . Whereas, the diameter of G is the maximum distance between any pair of vertices in G.

By and we denote the path and complete graph on n vertices, respectively.

In [

3], for a vertex

u of

G, the

closeness of u in G is defined as

The closeness of

G is defined as

A

bipartite graph is a graph in which

can be divided into two disjoint subsets

and

such that no two vertices within the same set are adjacent. A bipartite graph in which every two vertices from different partition classes are adjacent is called complete, and it is denoted by

, where

. Bipartite graphs serve as powerful tools for modeling complex systems with two distinct sets of entities, enabling analyses of and solutions to a wide range of real-world problems across different domains [

22,

23].

The (vertex) connectivity of a graph G is the minimum number of vertices whose removal from G results in a disconnected graph or in the trivial graph, and it is denoted by . If G is trivial or disconnected, then , obviously. An edge e of a connected graph G is a cut edge if is disconnected. A subset is called a dissociation set if the induced subgraph does not include as a subgraph. A maximum dissociation set of G is one with the greatest cardinality. Finally, the dissociation number of G is the cardinality of a maximum dissociation set within G.

In order to explore the connection between closeness and the structural characteristics of a graph, we will investigate extremal problems aimed at maximizing closeness within certain classes of bipartite graphs.

2. Main Results

In this section we will state our results. Specifically, we will determine those graphs which maximize closeness over the bipartite graphs of order n and one of the fixed parameters, such as dissociation number, connectivity, cut edges, and diameter.

The following Lemma will be helpful for the proofs of the main results.

Lemma 1 ([

3,

12])

. If u and v are vertices in a graph G where there is no edge between them, then adding the edge increases the closeness of G. Our first main result establishes an upper bound on the closeness of a bipartite graphs with a fixed order and dissociation number , and identified the graph that attain the bound.

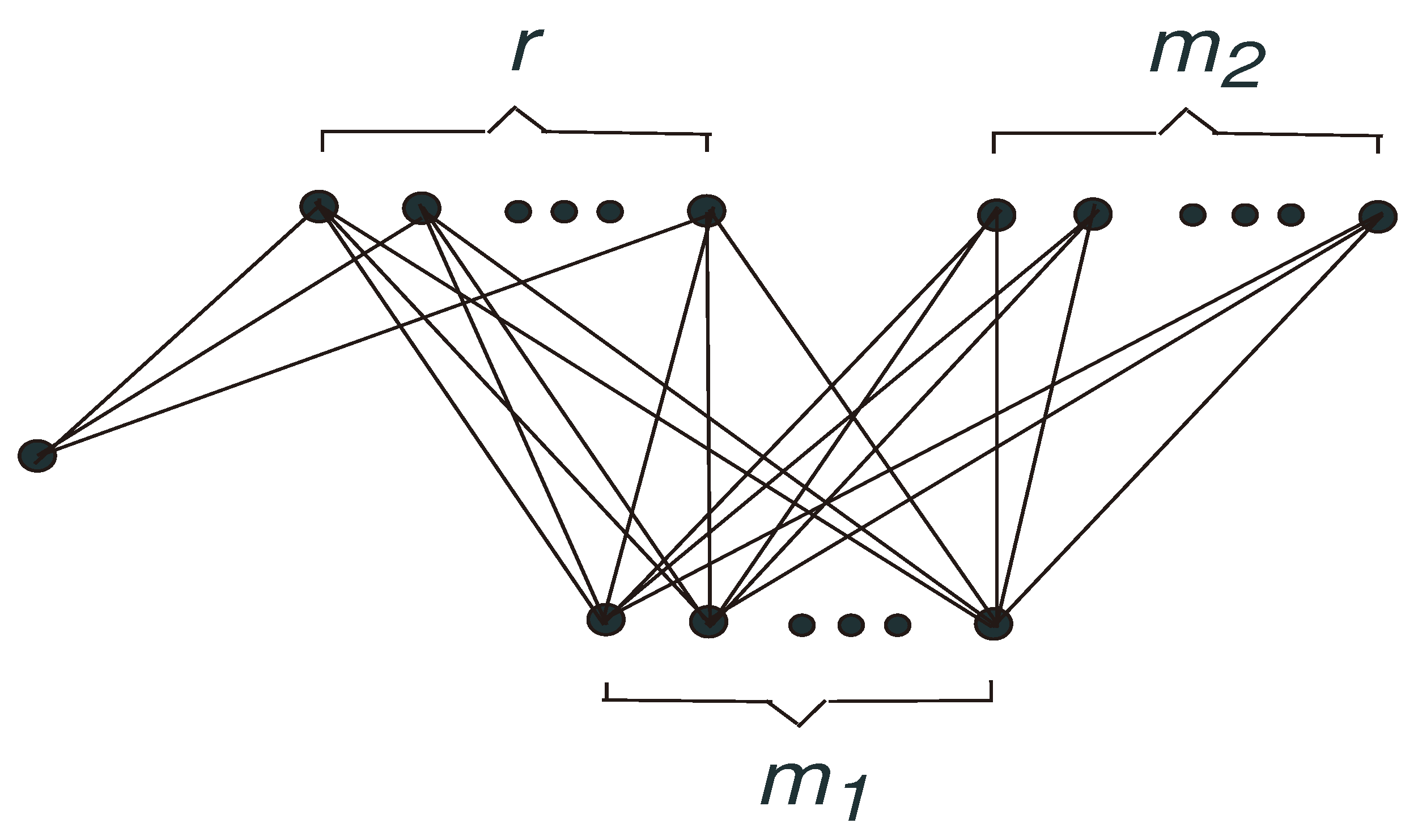

Theorem 1. Let G be a bipartite graph of order n with dissociation number α. Then,with equality if and only if . For

, we define

as the graph comprising

r isolated vertices. Let

be the graph obtained from

and

by adding the edges between the vertices in

and the vertices belonging to partitions of size

in

and

, respectively (see

Figure 1). It is evident that

.

Our second result identifies the graph that maximizes the closeness within bipartite graphs of order n and fixed connectivity r.

Theorem 2. Let G be a bipartite graph of order n with connectivity r, where . Then,with equality if and only if . For positive integers

s,

ℓ, and

n, where

, let

be the graph obtained by attaching

ℓ pendent vertices to a vertex with degree

in

(see

Figure 2).

The next result characterizes all bipartite graphs with

n vertices and

ℓ cut edges having the largest closeness.

Theorem 3. Let G be a bipartite graph of order with ℓ cut edges.

- (i)

If , then with equality if and only if ;

- (ii)

If , then with equality if and only if .

In the following cases, .

- (iii)

If mod , then with equality if and only if ;

- (iv)

If mod , then with equality if and only if ;

- (v)

If mod , then with equality if and only if ;

- (vi)

If mod , then with equality if and only if ;

- (vii)

If mod , then with equality if and only if ;

- (viii)

If mod , then with equality if and only if .

In a bipartite graph

G with

n vertices and diameter

d, suppose

represents a diametrical path of

G. We can then partition

as follows:

where

and

for

.

Let

where

d is odd. Let

where

d is even, and

.

Clearly, is a bipartite graph of order n with diameter d, and is a set of n-vertex bipartite graphs having diameter d.

Evidently, (resp. ) is the unique bipartite graph of diameter one (resp. ). In what follows, we consider .

Our last main result identifies the bipartite graphs with n vertices and diameter d that maximize the closeness.

Theorem 4. Let G be a bipartite graph of order n with diameter d having maximum closeness.

If , then ;

If , then for odd d, and otherwise.

3. Proof of Theorem 1

In this section, we give the proof of Theorem 1, which establishes an upper bound on the closeness of a bipartite graphs with a fixed order and dissociation number , and we identify the graph that attains the bound.

Proof. Let G be a bipartite graph of order n and dissociation number that maximizes . Denote the partition of as , assuming without loss of generality that . Let Q be the maximum dissociation set of G. Then . If , then by Lemma 1, .

Now, we consider the case where . Let with , , and , . It can be observed that and . Since G is a bipartite graph with maximum closeness, by Lemma 1, each vertex in (resp. ) is adjacent to each vertex in (resp. ).

If

, then there exists

with

such that

forms a perfect matching. Thus, we have:

and

We deduce,

Note that since

G is connected, we have

. If

, then

, implying

. If

, then

, and thus

, which contradicts .

If

, then by a similar argument as above, we arrive at a contradiction to the choice of

G. Therefore,

. By direct calculation, we obtain:

□

4. Proof of Theorem 2

To establish the main result, we first require the following Lemma.

Lemma 2. Let and r be positive integers.

If , then ;

If , then .

Proof. By the definition of closeness, we have

and

If

, we have

Thus,

If

, we have

Thus,

□

By Lemma 3 , we immediately get the following Corollary.

Corollary 1. If , then .

Proof. By direct calculation, we have

Let G be a bipartite graph of order n and connectivity r such that is maximized. Let contain r vertices, and let be the components of , where . If any component of contains at least two vertices, then by Lemma 1, it must be a complete bipartite graph. If one of the components is a singleton set, denoted as , then v is adjacent to all vertices in W; otherwise, if G’s connectivity is less than r, contains isolated vertices.

Case 1. At least one component of comprises a minimum of two vertices.

In this case,

comprises exactly two components. Otherwise, by introducing some edges in

G, we would obtain a complete bipartite graph

among the vertices of

, with order

n and connectivity

r. According to Lemma 1,

, contradicting the maximality of

G. Let

and

be the components of

G. Then either

or

. Otherwise,

has the partitions

and

, respectively. Let

represent the bipartition of

W. As

G possesses maximum closeness, by Lemma 1, there must exist edges between the vertices of

and

,

and

,

and

. Considering the definition of closeness, we have:

Note that

, and

. Let

, and

. Clearly,

is a bipartite graph of order

n having vertex cut

contain

r vertices. We have

So

this leads to a contradiction. Without loss of generality, let us assume that

. Then,

, and

u is connected to all vertices of

W, while each vertex of

W is connected to every vertex of

that is in the same partition as

u. Thus,

, where

, and

. Since

G maximizes closeness, by Lemma 3, we have

, which implies

.

Case 2. All components of consist of a single vertex.

In this case . By Corollary 1, .

Hence, . □

5. Proof of Theorem 3

Lemma 3 ([

19])

. Let G represent a connected graph containing a cut edge . Let denote the graph resulting from contracting edge e into a new vertex w, which becomes adjacent to every vertex in except for u and v, and then attaching a pendent edge at w. Then . Lemma 4. Let be the two vertices on the same partition of a complete bipartite graph H, and G be a graph formed from H by attaching pendent vertices (resp. ) to u (resp. v) . Let . Then, .

Proof. By the definition of closeness, we have

Hence,

. □

Lemma 5. Let be a graph with vertex partition and , and G be a graph obtained from by attaching pendent vertices (resp. ) to (resp. ) . Let . Then, .

Proof. By the definition of closeness, we have

Hence,

. □

Proof. For , stands as the unique bipartite graph, with its closeness calculated directly as .

Consider a bipartite graph G of order n containing ℓ cut edges, maximizing . Note that for any bipartite graph with ℓ cut edges, and . Hereafter, we consider the case . Let denote the ℓ cut edges of G. Our claim is that each component of forms either a single vertex or a complete bipartite graph.

Suppose there exists a component H of that is not a complete bipartite graph. Let be the graph formed by adding an edge between two vertices from different partitions in H. Then, according to Lemma 1, , contradicting the selection of G. Thus, each component of is either a single vertex or a complete bipartite graph. By Lemma 3, must be pendent edges in G. Since G is a complete bipartite graph, these edges must be incident to a single vertex, denoted as s. Therefore, by Lemmas 4 and 5.

By direct calculation, we have

For

, we get

with equality if and only if

.

For

, we obtain

Therefore, we get

This completes the proof. □