A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition and Its Application to the Bay of Bengal Region—Part I: Flat Bottom Topography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme

2.1. Statement of the Problem

2.2. Presentation of the Scheme

- We need and due to the lack of the functions and for , which are used for and for .

- The so-called quadrilateral elements , e.g., bilinear and biquadratic elements, with a partition of , , by rectangles are also available for and .

3. Numerical Results in Square Domains

3.1. Experimental Order of Convergence

3.2. Effect of the TBC

- (a)

- , i.e., ,

- (b)

- (bottom), ,

- (c)

- (right and bottom), ,

- (d)

- (right, bottom and top), ,

- (e)

- .

4. Application to the Bay of Bengal

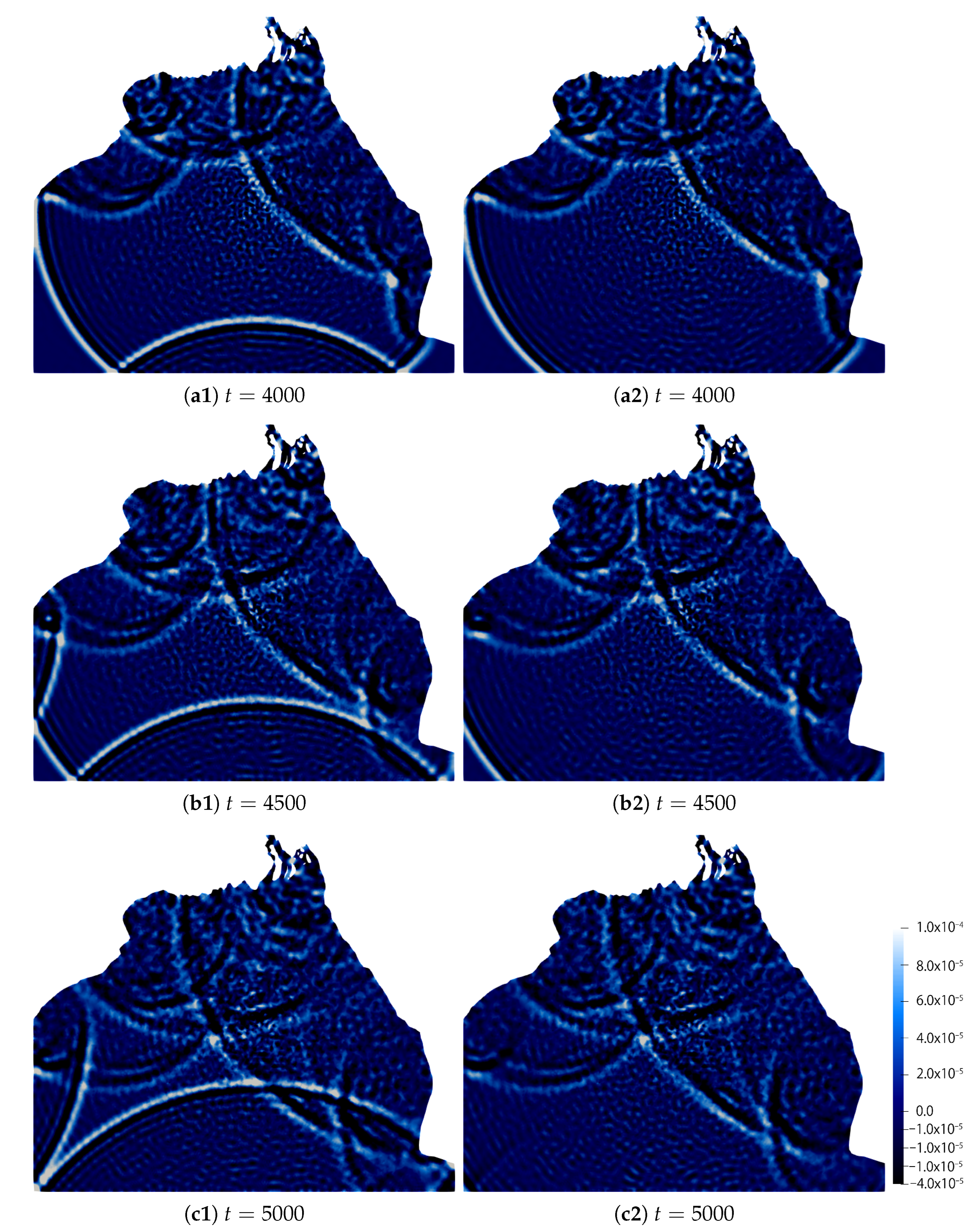

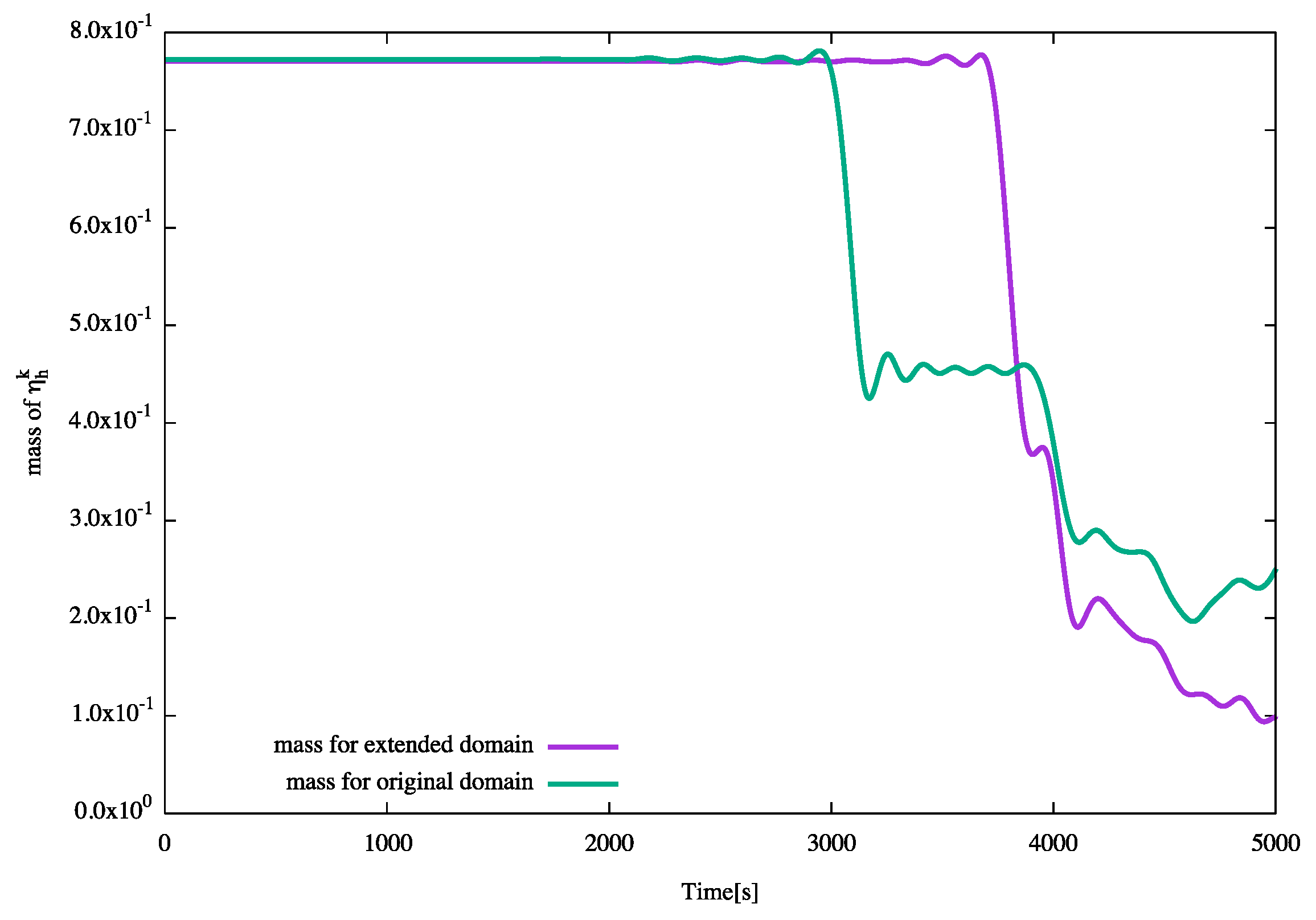

4.1. Numerical Simulation with and without the TBC

- (i)

- (ii)

- Let us additionally introduce a theorem ([9] (Theorem 3.4)). Suppose that there exists such thatThen, the summation of the first and second terms in the RHS of Equation (7) is non-positive, i.e.,in particular,

- (iii)

- (iv)

- We have compared our results by the TBC () and a modified TBC () with those by the RBC:The results by the three boundary conditions are not significantly different as presented in Appendix B. We note that condition (9) is the well-known RBC, cf., e.g., [8], and that the modified TBC is obtained by replacing ζ with in Equation (9), where the relation holds if is satisfied.

4.2. Effect of Position of a Transmission Boundary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RBC | Radiation boundary condition |

| TBC | Transmission boundary condition |

| SWEs | Shallow water equations |

| EOC | Experimental order of convergence |

| LG1 | Single-step Lagrange–Galerkin scheme of first order in time |

| LG2 | Two-step Lagrange–Galerkin scheme of second order in time |

Appendix A. Choice of c0

- -

- Case I (the square domain). In problem (3), we set , , , , , , , , , and . We employ discretization parameters, , and .

- -

- Case II (the Bay of Bengal). The parameters are the same as Example 4 except the value of . We employ the same mesh and in Section 4.

| Value of | Case I (the Square Domain) | Case II (the Bay of Bengal) |

|---|---|---|

| 13.55 | ||

| 13.54 | ||

| 13.5342 | ||

| 13.5323 | ||

| 13.5319 | ||

| 13.5328 | ||

| 13.5354 | ||

| 13.5375 | ||

Appendix B. Comparison with Radiation Type Open Boundary Condition

| Boundary Condition | Case I (the Square Domain) | Case II (the Bay of Bengal) |

|---|---|---|

| TBC | 13.5316 | |

| modified TBC with | 13.5328 | |

| RBC | 13.5334 | |

References

- Debsarma, S.K. Simulations of storm surges in the Bay of Bengal. Mar. Geod. 2009, 32, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K. Prediction Model for Storm Surges in the Bay of Bengal. Nature 1972, 239, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, B. Numerical simulation of storm surges in the Bay of Bengal. In Monsoon Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; pp. 689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, G.; Kabir, A.H.; Mandal, M.; Haque, M. Polar coordinates shallow water storm surge model for the coast of Bangladesh. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 1999, 29, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.C.; Ismail, A.I.M. Tide–surge interaction model including air bubble effects for the coast of Bangladesh. J. Frankl. Inst. 2012, 349, 2530–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.C.; Ismail, A.I.M. Contribution of offshore islands in the prediction of water levels due to tide–surge interaction for the coastal region of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2013, 65, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.C.; Senthilkumar, S.; Pria, R. Storm surge simulation along the Meghna estuarine area: An alternative approach. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2018, 37, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.; Sinha, P.; Roy, G. Numerical simulation of storm surges in Bangladesh using a bay-river coupled model. Coast. Eng. 1986, 10, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.M.; Futai, K.; Kimura, M.; Notsu, H. Theoretical and numerical studies for energy estimates of the shallow water equations with a transmission boundary condition. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-S 2021, 14, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.M. Theoretical and Numerical Studies of the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition. Ph.D. Thesis, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfeld, A. Partial Differential Equations: Lectures in Theoretical Physics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1949; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Orlanski, I. A simple boundary condition for unbounded hyperbolic flows. J. Comput. Phys. 1976, 21, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røed, L.P.; Cooper, C.K. Open Boundary Conditions in Numerical Ocean Models. Adv. Phys. Oceanogr. Numer. Model. 1986, 186, 411–436. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.G. Open boundary conditions in stratified ocean models. J. Mar. Syst. 1998, 16, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, H.; Dan, H. Tsunami Propagation from the open sea to the coast. In Tsunami; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama, H.; Dan, H. A finite element scheme for two-layer viscous shallow-water equations. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 2006, 23, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Russell, T. Multistep Galerkin methods along characteristics for convection-diffusion problems. In Advances in Computer Methods for Partial Differential Equations IV; Vichnevetsky, R., Stepleman, R., Eds.; IMACS: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.J.; Russell, T.F. Numerical Methods for Convection-Dominated Diffusion Problems Based on Combining the Method of Characteristics with Finite Element or Finite Difference Procedures. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1982, 19, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironneau, O. On the transport-diffusion algorithm and its applications to the Navier-Stokes equations. Numer. Math. 1982, 38, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, H.; Tabata, M. A mass-conservative characteristic finite element scheme for convection-diffusion problems. J. Sci. Comput. 2010, 43, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Russell, T.; Wheeler, M. Simulation of miscible displacement using mixed methods and a modified method of characteristics. In Proceedings of the Seventh Reservoir Simulation Symposium; Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Süli, E. Convergence and nonlinear stability of the Lagrange-Galerkin method for the Navier-Stokes equations. Numer. Math. 1988, 53, 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironneau, O. Finite Element Methods for Fluids; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boukir, K.; Maday, Y.; Métivet, B.; Razafindrakoto, E. A high-order characteristics/finite element method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1997, 25, 1421–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achdou, Y.; Guermond, J.L. Convergence analysis of a finite element projection/Lagrange–Galerkin method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2000, 37, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, H.; Tabata, M. A second order characteristic finite element scheme for convection-diffusion problems. Numer. Math. 2002, 92, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, A.; Nogueiras, M.R.; Vázquez, C. Numerical analysis of convection-diffusion-reaction problems with higher order characteristics/finite elements. Part I: Time Discretization. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2006, 44, 1829–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, A.; Nogueiras, M.R.; Vázquez, C. Numerical analysis of convection-diffusion-reaction problems with higher order characteristics/finite elements. Part II: Fully discretized scheme and quadrature formulas. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2006, 44, 1854–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysafinos, K.; Walkington, N.J. Lagrangian and moving mesh methods for the convection diffusion equation. ESAIM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2008, 42, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, H. Numerical computations of cavity flow problems by a pressure stabilized characteristic-curve finite element scheme. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2008, 2008, 20080032. [Google Scholar]

- Pironneau, O.; Tabata, M. Stability and convergence of a Galerkin-characteristics finite element scheme of lumped mass type. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2010, 64, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, M.; Bermúdez, A. A second order characteristics finite element scheme for natural convection problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2011, 235, 3270–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, M.; Bermúdez, A. Numerical analysis of a second order pure Lagrange–Galerkin method for convection-diffusion problems. Part I: Time discretization. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2012, 50, 858–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, M.; Bermúdez, A. Numerical analysis of a second order pure Lagrange–Galerkin method for convection-diffusion problems. Part II: Fully discretized scheme and numerical results. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2012, 50, 2824–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, R.; Saavedra, L. Modified Lagrange–Galerkin methods of first and second order in time for convection-diffusion problems. Numer. Mathematik 2012, 120, 601–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, R.; Gálan del Sastre, P.; Saavedra, L. A second order in time modified Lagrange–Galerkin finite element method for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2012, 50, 3084–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, H.; Rui, H.; Tabata, M. Development and L2-Analysis of a Single-Step Characteristics Finite Difference Scheme of Second Order in Time for Convection-Diffusion Problems. J. Algorithms Comput. Technol. 2013, 7, 343–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, H.; Tabata, M. Error Estimates of a Pressure-Stabilized Characteristics Finite Element Scheme for the Oseen Equations. J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 65, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, H.; Tabata, M. Error estimates of a stabilized Lagrange–Galerkin scheme for the Navier–Stokes equations. ESAIM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2016, 50, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, H.; Tabata, M. Error Estimates of a Stabilized Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme of Second-Order in Time for the Navier–Stokes Equations. In Mathematical Fluid Dynamics, Present and Future Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 497–530. [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, M.; Uchiumi, S. A genuinely stable Lagrange–Galerkin scheme for convection-diffusion problems. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 2016, 33, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukáčová-Medviďová, M.; Notsu, H.; She, B. Energy dissipative characteristic schemes for the diffusive Oldroyd-B viscoelastic fluid. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2015, 81, 523–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukáčová-Medvid’ová, M.; Mizerová, H.; Notsu, H.; Tabata, M. Numerical analysis of the Oseen-type Peterlin viscoelastic model by the stabilized Lagrange–Galerkin method, Part I: A linear scheme. ESAIM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2017, 51, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukáčová-Medvid’ová, M.; Mizerová, H.; Notsu, H.; Tabata, M. Numerical analysis of the Oseen-type Peterlin viscoelastic model by the stabilized Lagrange–Galerkin method, Part II: A nonlinear scheme. ESAIM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2017, 51, 1663–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, M.; Uchiumi, S. An exactly computable Lagrange–Galerkin scheme for the Navier–Stokes equations and its error estimates. Math. Comput. 2018, 87, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiumi, S. A viscosity-independent error estimate of a pressure-stabilized Lagrange–Galerkin scheme for the Oseen problem. J. Sci. Comput. 2019, 80, 834–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colera, M.; Carpio, J.; Bermejo, R. A nearly-conservative high-order Lagrange–Galerkin method for the resolution of scalar convection-dominated equations in non-divergence-free velocity fields. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 372, 113366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colera, M.; Carpio, J.; Bermejo, R. A nearly-conservative, high-order, forward Lagrange–Galerkin method for the resolution of scalar hyperbolic conservation laws. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 376, 113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futai, K.; Kolbe, N.; Notsu, H.; Suzuki, T. A mass-preserving two-step Lagrange–Galerkin scheme for convection-diffusion problems. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 92, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, F. New development in FreeFem++. J. Numer. Math. 2012, 20, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LG1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | EOC | EOC | |||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.65 | 1.45 | |||

| 32 | 1.19 | 1.09 | |||

| 64 | 1.05 | 1.03 | |||

| 128 | 1.01 | 1.00 | |||

| 256 | 1.00 | 0.99 | |||

| LG1 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.59 | 1.49 | |||

| 32 | 0.93 | 1.31 | |||

| 64 | 0.71 | 1.06 | |||

| 128 | 1.22 | 1.04 | |||

| 256 | 1.12 | 1.01 | |||

| LG2 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 3.60 | 2.57 | |||

| 32 | 2.40 | 2.16 | |||

| 64 | 2.32 | 2.04 | |||

| 128 | 2.05 | 1.99 | |||

| 256 | 1.97 | 1.95 | |||

| LG2 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.65 | 1.94 | |||

| 32 | 0.33 | 2.54 | |||

| 64 | 0.57 | 1.67 | |||

| 128 | 0.97 | 2.11 | |||

| 256 | 0.88 | 2.28 | |||

| LG1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | EOC | EOC | |||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.65 | 1.46 | |||

| 32 | 1.19 | 1.11 | |||

| 64 | 1.05 | 1.03 | |||

| 128 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| 256 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| LG1 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.57 | 1.50 | |||

| 32 | 0.94 | 1.31 | |||

| 64 | 0.67 | 1.07 | |||

| 128 | 1.21 | 1.04 | |||

| 256 | 1.13 | 1.01 | |||

| LG2 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 3.56 | 2.55 | |||

| 32 | 2.37 | 2.20 | |||

| 64 | 2.22 | 2.03 | |||

| 128 | 2.17 | 2.00 | |||

| 256 | 1.94 | 1.96 | |||

| LG2 | |||||

| EOC | EOC | ||||

| 8 | - | - | |||

| 16 | 1.63 | 1.92 | |||

| 32 | 0.32 | 2.49 | |||

| 64 | 0.54 | 1.69 | |||

| 128 | 0.97 | 2.16 | |||

| 256 | 0.89 | 2.27 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rasid, M.M.; Kimura, M.; Murshed, M.M.; Wijayanti, E.R.; Notsu, H. A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition and Its Application to the Bay of Bengal Region—Part I: Flat Bottom Topography. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11071633

Rasid MM, Kimura M, Murshed MM, Wijayanti ER, Notsu H. A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition and Its Application to the Bay of Bengal Region—Part I: Flat Bottom Topography. Mathematics. 2023; 11(7):1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11071633

Chicago/Turabian StyleRasid, Md Mamunur, Masato Kimura, Md Masum Murshed, Erny Rahayu Wijayanti, and Hirofumi Notsu. 2023. "A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition and Its Application to the Bay of Bengal Region—Part I: Flat Bottom Topography" Mathematics 11, no. 7: 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11071633

APA StyleRasid, M. M., Kimura, M., Murshed, M. M., Wijayanti, E. R., & Notsu, H. (2023). A Two-Step Lagrange–Galerkin Scheme for the Shallow Water Equations with a Transmission Boundary Condition and Its Application to the Bay of Bengal Region—Part I: Flat Bottom Topography. Mathematics, 11(7), 1633. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11071633