Metric Dimensions of Bicyclic Graphs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

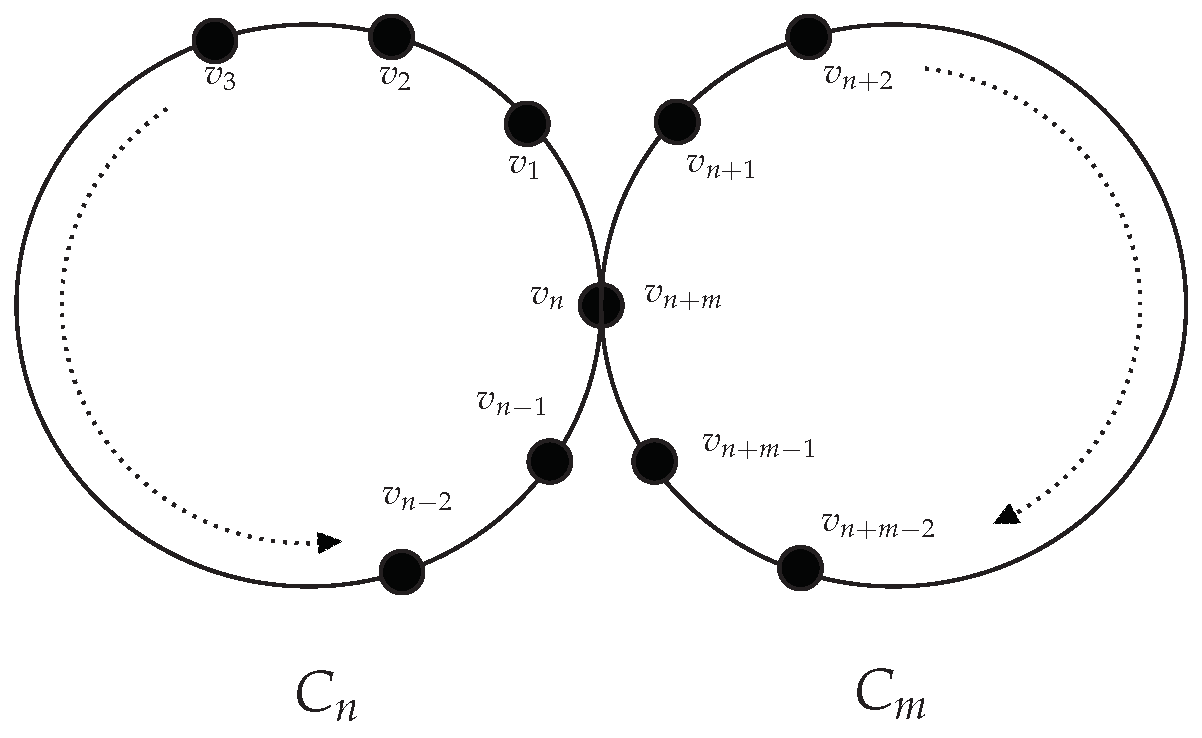

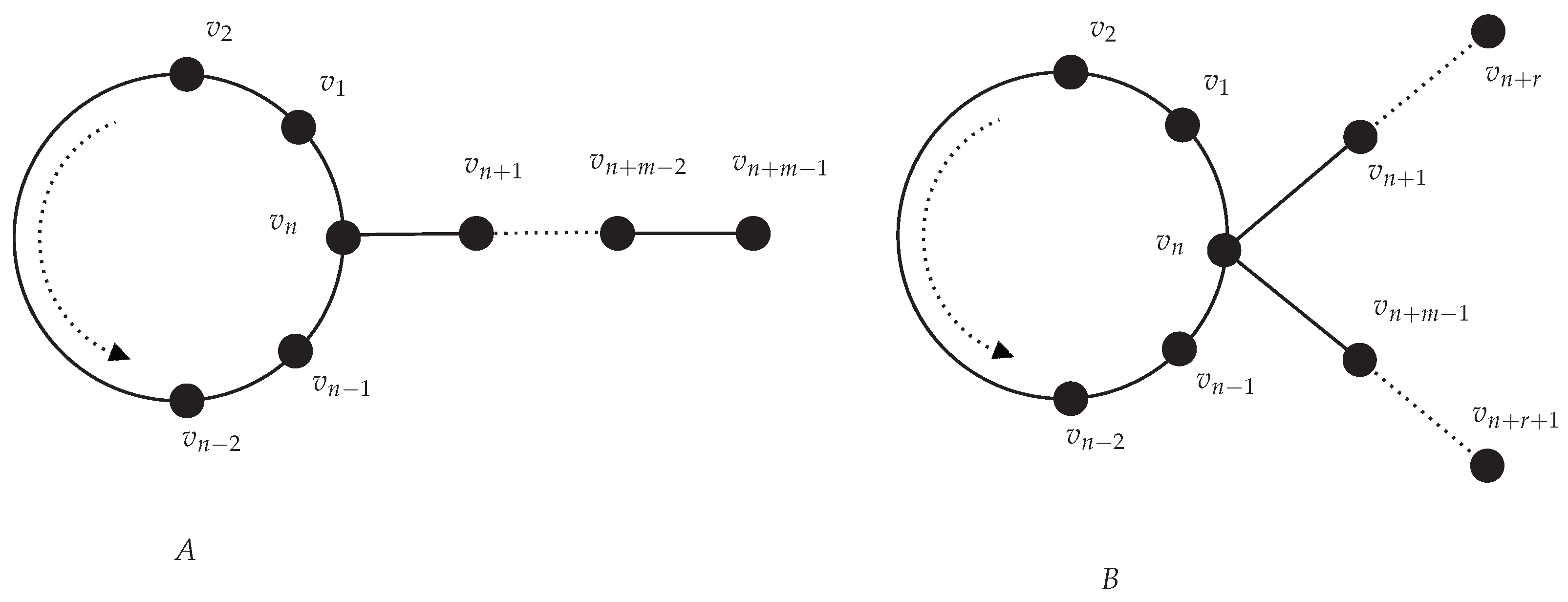

- obtained from two disjoint cycles and , where and share a single vertex. Let us label the vertices as given in Figure 1.The vertices of and of are identified together as the common vertex in this labeling. Note that the vertices of are labeled anti-clockwise, while vertices of are labeled clockwise.

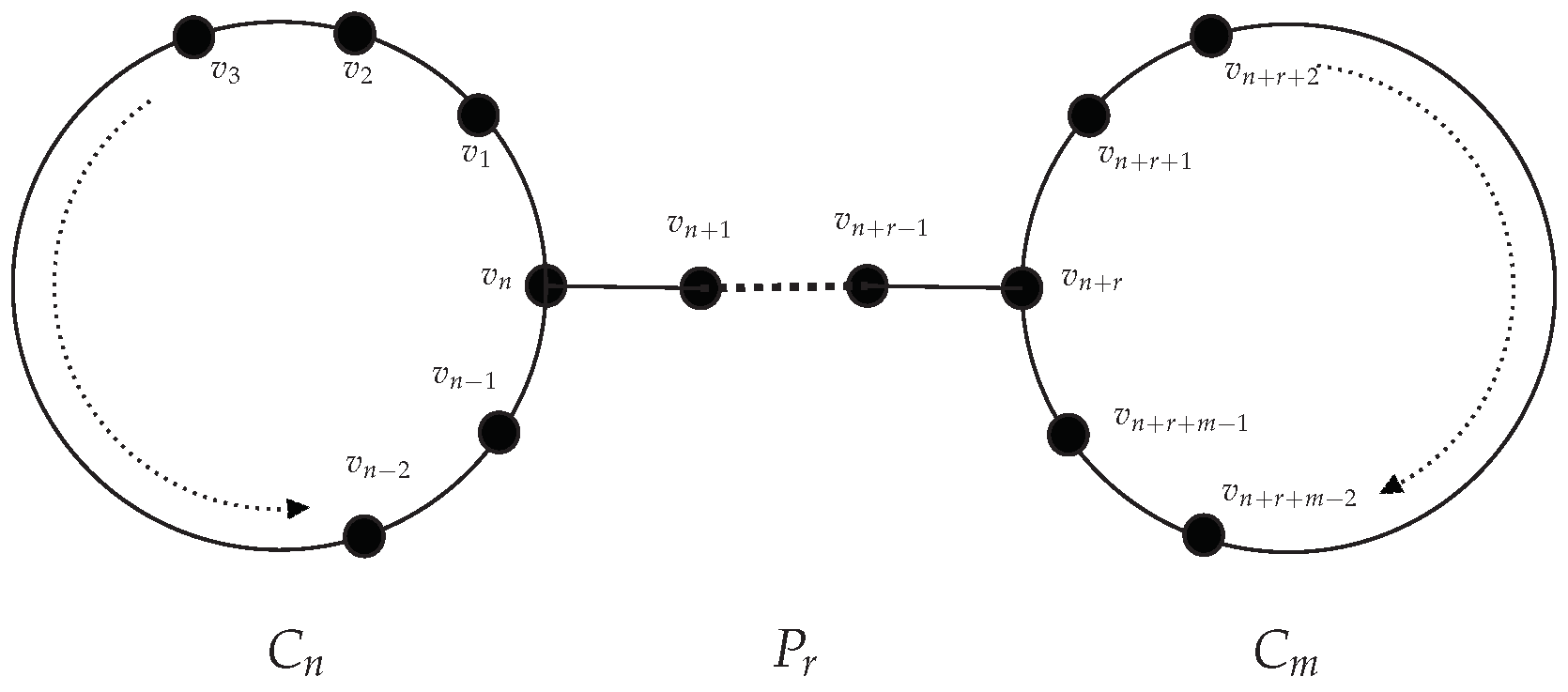

- obtained from two disjoint cycles and , by adding a path , from any vertex of to any vertex of . Let us consider the labeling given in Figure 2.In this labeling, the vertex of is attached to the vertex of , by a path of length r.

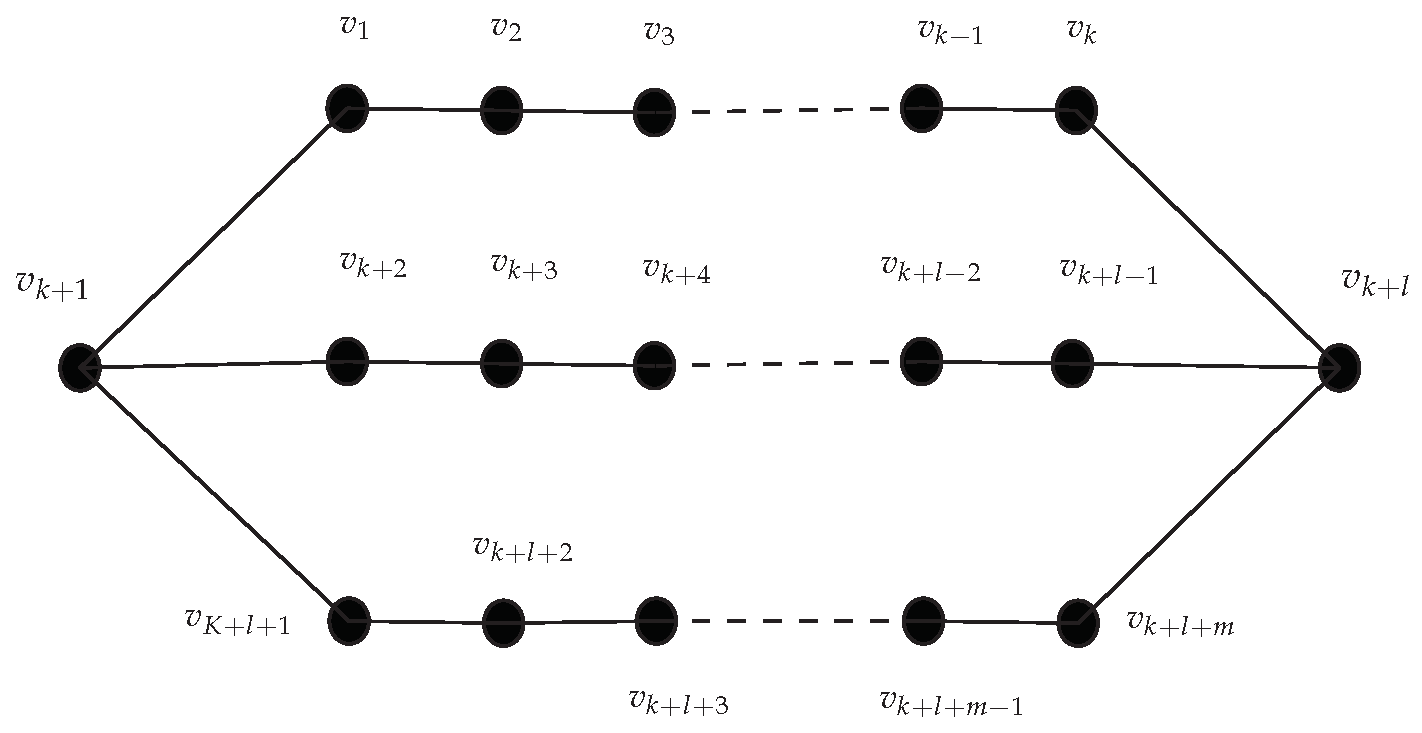

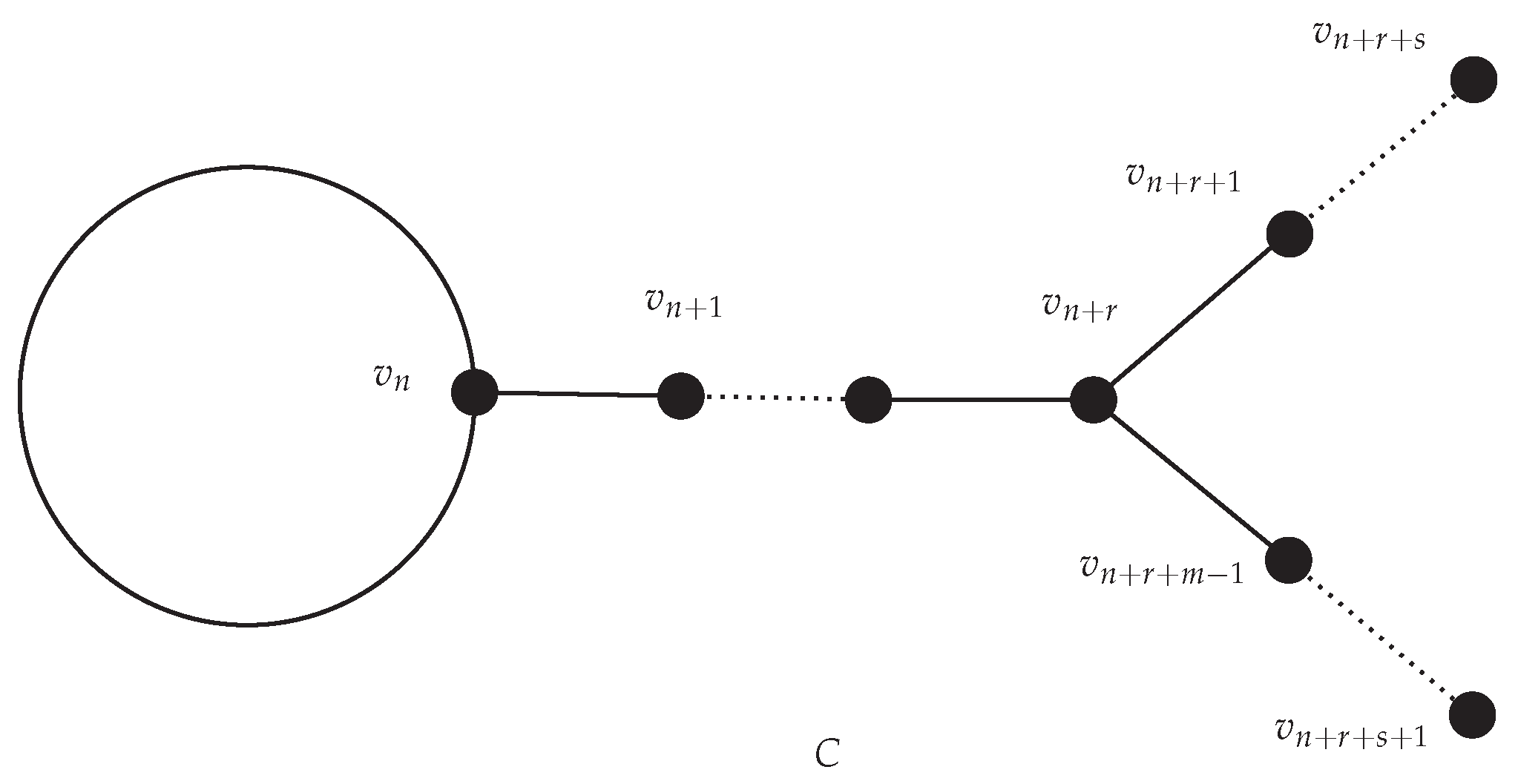

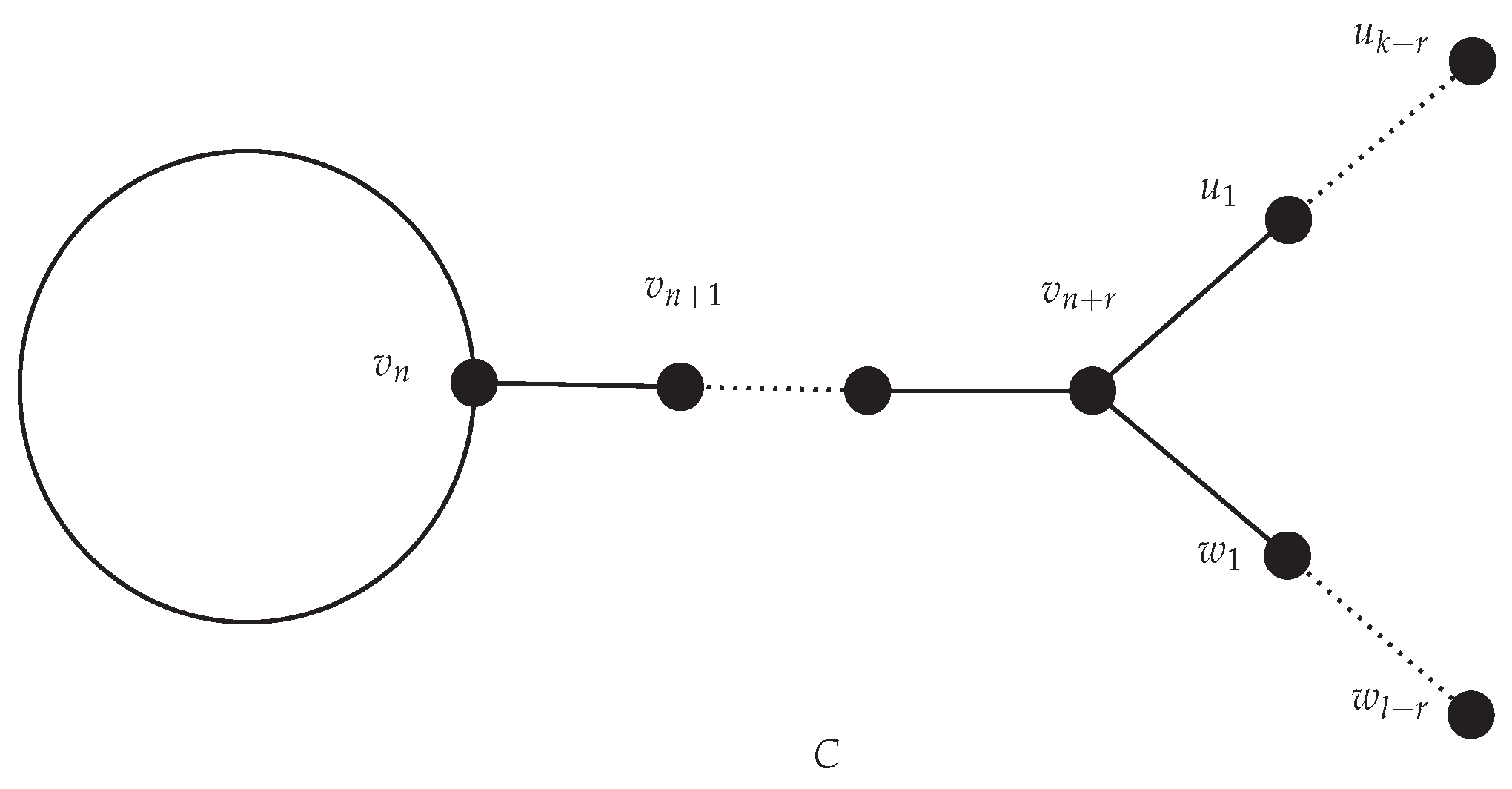

- obtained from three pairwise internal disjoint paths , , and , by joining starting vertices of and to the starting vertex of , and ending vertices of and , to the ending vertex of . Let us denote the vertices of this graph as , then this type of bicyclic graph is given in Figure 3.Note that the starting vertices of paths, i.e., of , of , and of , are joined together. The same is applied to the ending vertices of paths.

3. Results on Bicyclic Graphs of Type I

4. Results on Bicyclic Graphs of Type II

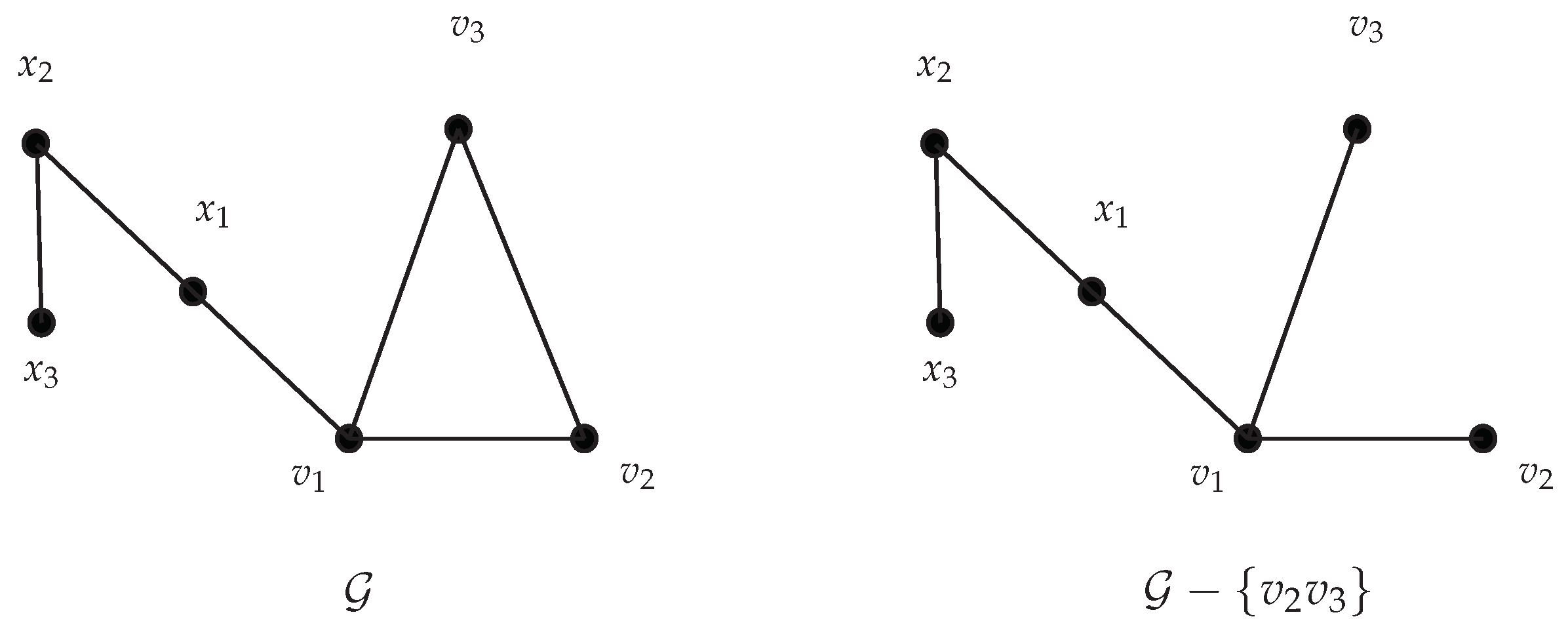

5. Perturbation in Metric Dimension of Bicyclic Graphs after Edge/Vertex Deletion

6. Summary

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slater, P.J. Leaves of trees. Congr. Numer. 1975, 14, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, P.J. Dominating and reference sets in a graph. J. Math. Phys. Sci. 1988, 22, 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Melter, F.; Harary, F. On the metric dimension of a graph. Ars Comb. 1976, 2, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Eroh, L.; Johnson, M.A.; Oellermann, O.R. Resolvability in graphs and the metric dimension of a graph. Discret. Appl. Math. 2000, 105, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, D.J.; Yi, E. A comparison on metric dimension of graphs, line graphs, and line graphs of the subdivision graphs. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2012, 5, 302–316. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Sheikholeslami, S.; Wu, P.; Liu, J.B. The metric dimension of some generalized Petersen graphs. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khuller, S.; Raghavachari, B.; Rosenfeld, A. Landmarks in graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 1996, 70, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Structure-activity maps for visualizing the graph variables arising in drug design. J. Biopharm. Stat. 1993, 3, 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. Browsable structure-activity datasets. Adv. Mol. Similarity 1998, 2, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, J.; Hernando, C.; Mora, M.; Pelayo, I.M.; Puertas, M.L.; Seara, C.; Wood, D.R. On the metric dimension of cartesian products of graphs. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 2007, 21, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.F.; Meagher, K. On the metric dimension of Grassmann graphs. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1010.4495. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Wang, K. On the metric dimension of bilinear forms graphs. Discret. Math. 2012, 312, 1266–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Geneson, J.; Kaustav, S.; Labelle, A. Extremal results for graphs of bounded metric dimension. Discret. Appl. Math. 2022, 309, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkaria, S.; Odor, G.; Thiran, P. On the robustness of the metric dimension of grid graphs to adding a single edge. Discret. Appl. Math. 2022, 316, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melter, R.A.; Tomescu, I. Metric bases in digital geometry. Comput. Vision Graph. Image Process. 1984, 25, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Yero, I.G.; Kuziak, D.; Rodríguez-Velázquez, J.A. On the metric dimension of corona product graphs. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 61, 2793–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knor, M.; Sedlar, J.; Škrekovski, R. Remarks on the Vertex and the Edge Metric Dimension of 2-Connected Graphs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, L.; Basak, M.; Tiwary, K.; Das, K.C.; Shang, Y. On the Characterization of a Minimal Resolving Set for Power of Paths. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Khan, A.; Zhong, Y. On Resolvability- and Domination-Related Parameters of Complete Multipartite Graphs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, W.; Salman, A.; Saputro, S.W. Non-Isolated Resolving Sets of Corona Graphs with Some Regular Graphs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, F.; Phinezy, B.; Zhang, P. The local metric dimension of a graph. Math. Bohem. 2010, 135, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelenc, A.; Kuziak, D.; Taranenko, A.; Yero, I.G. Mixed metric dimension of graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 314, 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlar, J.; Škrekovski, R. Extremal mixed metric dimension with respect to the cyclomatic number. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 404, 126238. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Moreno, A.; Rodríguez-Velázquez, J.A.; Yero, I.G. The k-metric dimension of a graph. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6840. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlar, J.; Škrekovski, R. Bounds on metric dimensions of graphs with edge disjoint cycles. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 396, 125908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlar, J.; Škrekovski, R. Vertex and edge metric dimensions of unicyclic graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2022, 314, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.X.; Shao, J.Y.; He, J.L. On the Laplacian spectral radii of bicyclic graphs. Discret. Math. 2008, 308, 5981–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Y.; You, Z. The maximal total irregularity of bicyclic graphs. J. Appl. Math. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Baca, M.; Sultan, S. Computing the metric dimension of kayak paddles graph and cycles with chord. Proyecciones (Antofagasta) 2020, 39, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, J.; Pottonen, O.; Serna, M.; van Leeuwen, E.J. Complexity of metric dimension on planar graphs. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2017, 83, 132–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, A.; Haidar, G.; Abbas, N.; Khan, M.U.I.; Niazi, A.U.K.; Khan, A.U.I. Metric Dimensions of Bicyclic Graphs. Mathematics 2023, 11, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11040869

Khan A, Haidar G, Abbas N, Khan MUI, Niazi AUK, Khan AUI. Metric Dimensions of Bicyclic Graphs. Mathematics. 2023; 11(4):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11040869

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Asad, Ghulam Haidar, Naeem Abbas, Murad Ul Islam Khan, Azmat Ullah Khan Niazi, and Asad Ul Islam Khan. 2023. "Metric Dimensions of Bicyclic Graphs" Mathematics 11, no. 4: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11040869

APA StyleKhan, A., Haidar, G., Abbas, N., Khan, M. U. I., Niazi, A. U. K., & Khan, A. U. I. (2023). Metric Dimensions of Bicyclic Graphs. Mathematics, 11(4), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11040869