1. Introduction

The IoT paradigm allows us to design ecosystems and devices under the concepts of orchestration, choreography, and ubiquity of sensor and actuator devices connected to the Internet and interoperate with each other to accomplish a task. These concepts make the IoT architecture (perception layer, transport layer, and application layer) conceived for lightweight systems capable of guaranteeing coverage and data management through devices with limited processing, storage, and security resources [

1,

2]. The hardware characteristics in the perception layer of the IoT architecture require specificity in size, interoperability, processing, power, position, and storage according to the technologies implemented and the application field.

Every day, more security issues are identified in IoT ecosystems deployed in application domains where data handling is sensitive. From an IoT architecture point of view, it is possible to manage system security at any layer. However, the most critical security issue is maintaining data integrity from the source (sensor) at the perception layer, through the transport layer, to the user at the application layer. This process is known as the information transmission path.

Generally, data integrity is lost or in doubt when the information passes through intermediary devices or managers at the transport layer of the IoT architecture. The most popular solution to security issues related to data integrity is currently implemented at the application layer through the authentication protocol. Usually, the IoT device is authenticated to authorize or prevent unauthorized participants in the network and guarantee the origin of the information, conferring certainty of the data by identifying the transmission source [

3]. However, the more intermediary devices act between the information source (sensor) and the destination (application), the higher the risk of data corruptibility because they act as open access points to the data flow. Open access points in an IoT system are attributed to the incompatibility of architectures between the hardware firmware and the software that governs the IoT ecosystem.

The communication protocol defines the security of the system and the interoperability of the devices involved in many ways. For example, a sensor device housed in the perception layer has resources to acquire data and transmit them to a breaker device housed in the transport layer, which is responsible for collecting, managing, and sending the information to a superior entity accountable for storing and processing data before they are transmitted to the end-user [

4]. For this reason, IoT systems design requires a high degree of technological compatibility and interoperability of devices. However, most devices do not have free access to the firmware and specific configurations needed to generate adaptability in security requirements, giving rise to one of the principal vulnerabilities of IoT architectures in terms of security.

Blockchain is the foundation technology for crypto-assets with capabilities extended to various fields, including IT security. Blockchain and IoT define a new paradigm from the point of view of IoT systems as secure, decentralized, and transparent communication systems [

1]. A Blockchain–IoT system can manage information in a technologically controlled environment and allows for the massive deployment of incorruptible data securely and transparently. For the reasons above, Blockchain implementations to IoT systems have recently been proposed. However, applying this type of technology in IoT systems also requires implementing intermediary devices with specific processing capabilities (for processing cryptographic algorithms) and storage (due to the nature of the decentralized network). This alternative solves critical security problems in the transport and application layer of the IoT architecture by implementing architectural requirements (in devices) that fulfill the function of connection to the Blockchain. However, the advance that Blockchain represents concerning IoT security also reveals, due to the characteristics of the architecture (high processing and storage capacity), the impossibility of being implemented in the perception layer from the sensor where the data originate.

The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows: (i) the implementation of Blockchain technology in IoT systems from hardware development to achieve a marriage of architectures capable of avoiding intermediary devices and with the ability to operate across the perception, transport, and application layers of the IoT architecture, (ii) a proposal for the design of an information transmission path based on Blockchain–IoT, where the transmitted data are less prone to security attacks against integrity, (iii) the guarantee, in food traceability systems as in any other application field, of data traceability and certification in the collection and transmission of data.

This article is organized as follows:

Section 1 introduces the research context of this paper.

Section 2 presents the state-of-the-art review.

Section 2.1 details the Blockchain–IoT ecosystem description and the Blockchain–IoT in food safety context.

Section 3 presents the intrusion detection system (IDS) for the BIoTS network.

Section 4 introduces the results of the security assessment ecosystem for the BIoTS network.

Section 5 presents the conclusions.

2. Related Works

The raw source dataset for this state-of-the-art review stage was retrieved on 15 May 2023. The search equation used in the databases was (“SUPPLY CHAIN” AND BLOCKCHAIN AND IOT). After data reconciliation, we worked with 965 individual entries from both databases containing 366 unique articles from WoS and 599 unique articles from Scopus, removing 234 duplicate articles from Scopus. Finally, the bibliometric analysis was performed on 731 articles. This material will evaluate the trends and patterns of scientific production at the documentary level in information security in Blockchain–IoT-based supply chains.

Table 1 defines the abbreviations by which the ScientoPy program indicates growth according to scientific trend. The relative/absolute growth is determined and the h-index is calculated for each research area, as indicated in the tool manual [

5].

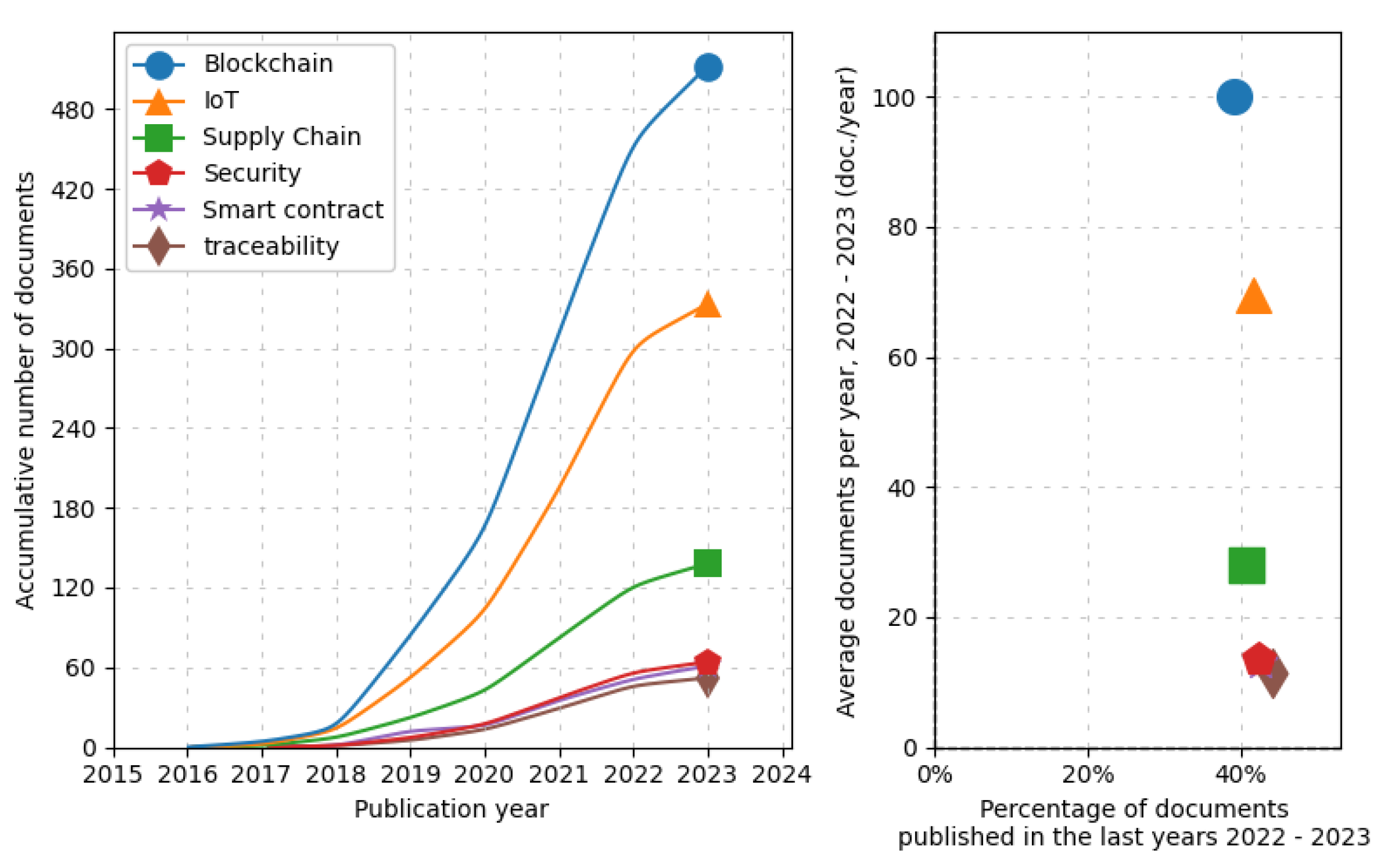

Figure 1 shows the five most outstanding topics in scientific production in the last two years. As shown in

Table 2, food traceability (supply chain) supports the application of technologies such as IoT and Blockchain to improve its performance in terms of security, decentralized deployment of information, and data transparency and integrity. In addition, the importance of programming smart contracts within the Blockchain to specify requirements and tasks within the supply chain process can be observed.

Security (privacy and data transparency) in systems and networks is one of the main concerns in applications. The diversification and capacity of the Internet through the implementation of IoT systems give rise to security problems in several dimensions: communication protocols, physical infrastructure, or architectures. For this reason, from the cybersecurity point of view, it is necessary to analyze existing attacks and their solutions, evaluate the technology and the communication protocol, characterize the network, and monitor the system [

6].

The expansion of Internet-related services (IoT) is creating new security and privacy challenges for the application of Blockchain technology [

7]. For this reason, Blockchain, conceived as a security system, can add transparency, integrity, and traceability to the data transported in an IoT-based system. This is how a very powerful (Blockchain–IoT) pairing is born in communication systems using sensitive data [

8,

9].

Food traceability systems (supply chains) implement an Internet-based process and product traceability and certification services [

10]. However, with the implementation of Blockchain technology, the system is robust, and data traceability is guaranteed [

11,

12].

With the implementation of smart contracts from the Blockchain network, decision-making criteria are established according to the data collected in communication systems, and specific actions are executed to fulfill quality standard requirements [

13,

14].

Table 3 shows the statistical behavior of the scientific production of the most influential research areas about supply chains. Food traceability (supply chain) supports the application of technologies such as IoT and Blockchain to improve its performance in terms of security, decentralized deployment of information, and data transparency and integrity. In addition, the importance of programming smart contracts within the Blockchain to specify requirements and tasks within the supply chain certification process can be observed.

In

Figure 2, we can see that the transparency and integrity in managing information in supply chains have become increasingly complex due to the capacity of the technologies, networks, and devices involved [

15]. They are becoming increasingly costly to maintain and require additional economic value in the market to be sustained. For this reason, implementation alternatives involving interoperability and the adaptation of technologies have been studied. The common denominator of these development efforts is focused on information management to ensure quality standards [

16].

Due to the characteristics of Blockchain technology, data traceability is directly guaranteed. However, the credibility in the collection of information from the physical devices of the Blockchain network to the end user imposes a challenge [

17,

18]. The main challenge imposed by the industry to ensure the quality of the processes is the involvement of the intervening actors and the efficient management of resources.

Agricultural supply chains have solved disorganized stakeholder participation in smart contracts and distributed networks. Tasks supervised by smart contracts, quality requirements, standards, and paradigms such as IoT have opened the door to technological integration and interoperability [

19,

20].

2.1. Blockchain–IoT-Based Food Traceability Systems

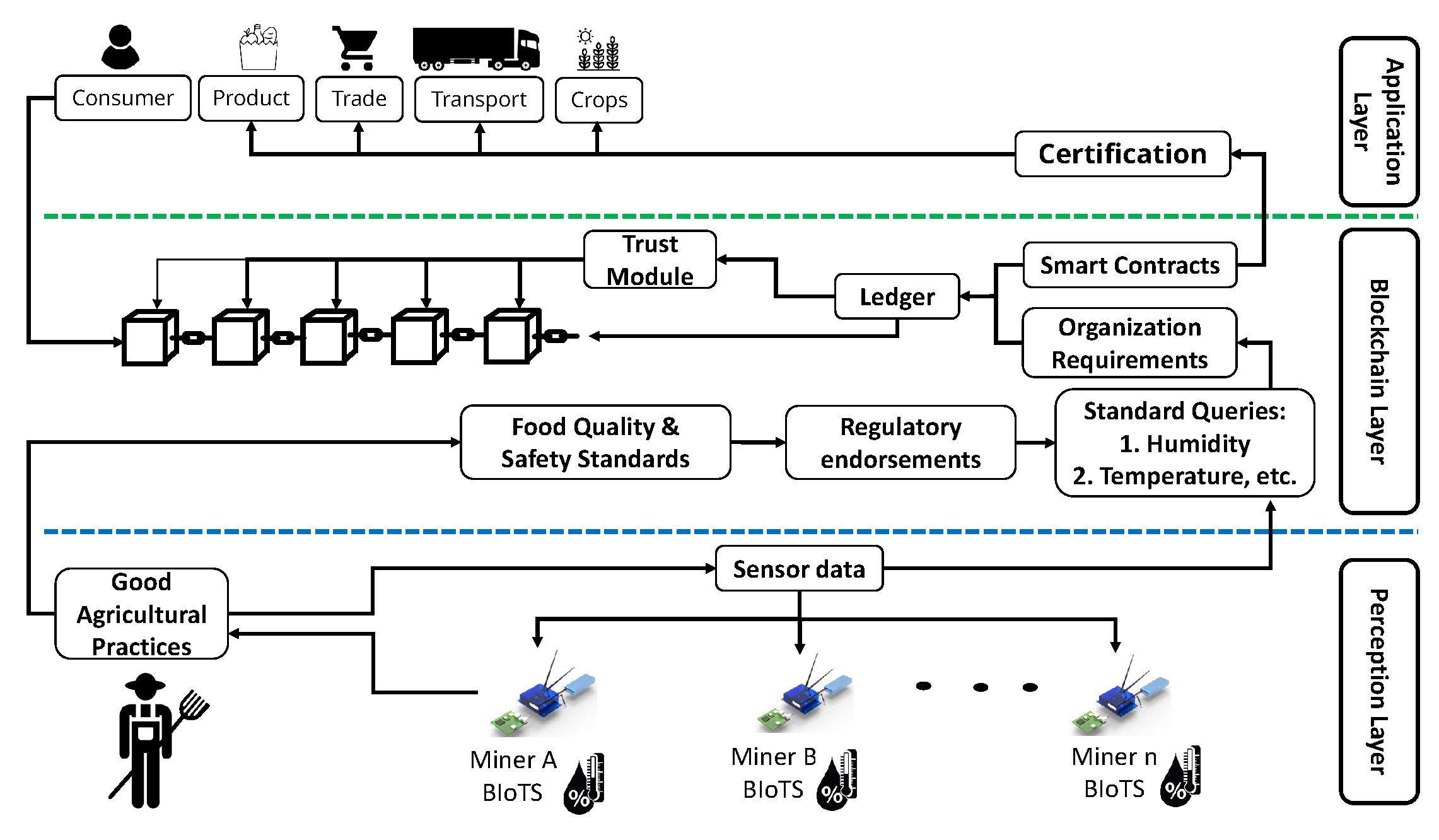

Figure 3 presents the abstraction of the Blockchain–IoT-based traceability system architecture. The figure is displayed over three axes: x, y, z. On the

z-axis are the six conventional stages that a food traceability system has. In this case, each stage is equipped with devices and technologies that make it possible to track the variables involved in the production process. This deployment is performed in the perception layer of the architecture. The red dot represents where tracing (backward traceability) or tracking (forward traceability) is intended to be carried out along the supply chain stages. In the perception layer and along the

z-axis, the coverage, type of network, and infrastructure required for traceability are configured. On the

x-axis of the figure, we can see the origin and destination of the data generated in the physical layer of the architecture (red dot). The data collected depend mainly on the devices deployed in the sensing layer and the transport layer setting.

The y-axis of the figure shows the infrastructure required to transmit data from their origin to the end-user. Above the perception layer is the transport layer. This layer manages the system according to network characteristics, physical devices, and communication channels required to secure data transport. Features such as interoperability, energy, storage, processing capacity, and security are evaluated to define scalability, robustness, accessibility, and security levels. Finally, in this axis, we find the application layer. This layer deploys the public access service to the data managed along the x, y, and z axes. These data move in the three directions coordinated to reach the end-user and thus certify processes or products. However, some features of IoT devices can be improved to ensure data integrity throughout transporting information across all layers of the architecture.

Blockchain implementation in some fields imposes scopes and limitations that in this work we assign to research challenges. Here, we highlight the transactional capacity, scalability, and security implicit in the participation of connected nodes in a distributed network through consensus algorithms and cryptography. However, enriching IoT with Blockchain is an ambitious proposition [

22].

Figure 4 shows the flow and logic of information passing through the BIoTS sensor and ecosystem (developed in previous work [

21]). Here, the BIoTS sensor is the starting point of the information transmission path that will certify data collected from the processes in a supply chain. In this way, the collected data will enjoy the security privileges of a Blockchain system through the information transmission path in an IoT architecture. However, it is necessary to evaluate the information transmission path in which BIoTS operates to ensure the integrity of the transmitted data.

With the implementation of information and communication technologies, food safety has made progress in terms of coverage in connection and accessibility of data. However, these resources are insufficient because there is no security guarantee in the data collected and transmitted in sensitive production sectors. IoT opens the door to Blockchain technology as a platform for data security. For this reason, Blockchain technology can solve critical security issues and the lack of transparent participation for the actors involved in food traceability systems (supply chains or value chains) [

23,

24].

2.1.1. Limitations of Blockchain Implementation in IoT-Based Food Traceability Systems

In the work related to the origin of the present [

21], the construction of the BIoTS hardware device was proposed and described. It was further determined that an architectural and functional (hardware–software) compatibility of Blockchain between layers is possible. This proposal could open the door to a security-enriched Blockchain–IoT ecosystem for data. Thus, in this work, the effort was focused on evaluating the security capabilities of the information transmission path of the BIoTS device, the BIoTS ecosystem, and the framework or architecture that certifies transmitted data. In general, this work evaluates the scientific approach of BIoTS, describing the technical and conceptual deployment of cybersecurity in networks and computing to propose an evaluation based on probabilistic statistics of the ecosystem operating in real-time.

The analysis in this section highlights the technological development gaps in implementing Blockchain technology in IoT systems. The works analyzed are chosen for their relevance concerning safeguarding data collected in ecosystems. The most relevant aspects in the justification of the design of the BIoTS ecosystem with a sensor architecture dedicated to Blockchain technology are the following:

The hardware architecture design dedicated to Blockchain technology in the IoT ecosystem and architecture makes a novel contribution to the adaptability of technologies and interoperability in the horizontal and vertical path of the architectural layers.

Blockchain and IoT technologies today impose a challenge regarding deep cooperativity for security at the boundaries or edges of the architecture layers where they are implemented. Architectures become highly complex to merge when firmware, hardware, and software security requirements are incompatible.

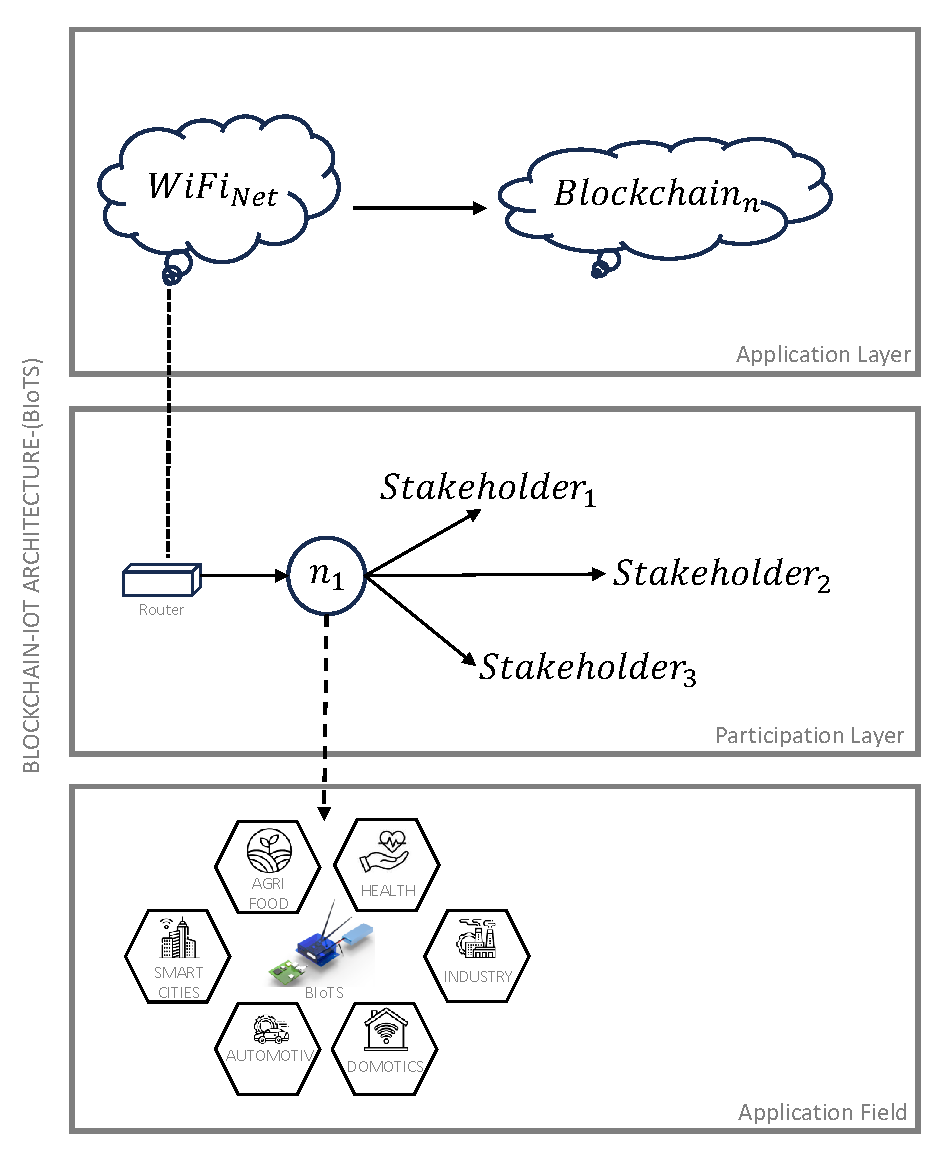

The scalability of BIoTS as an ecosystem and sensor device is high thanks to the intrinsic properties of each technology involved in its development. These characteristics make its implementation in various fields of application almost infinite; see

Figure 5.

As the goal of the BIoTS ecosystem and sensor device is to provide data security in an information transmission path by evaluating edges and boundaries of architectural layers, we find that it can certify data and processes in a broad spectrum of application fields.

Table 4 summarizes the state-of-the-art analysis concerning the limitations of Blockchain–IoT-based food traceability systems. Overall, it was found that implementing Blockchain technology in food traceability systems and other application fields needs proposals oriented to architectural adaptability and interoperability along the hardware–software line and across IoT architectural layers. The papers related here that are close to our concept are those listed in

Table 1 and were studied to identify the gaps that allow us to justify our work. The analysis is made from two points of view: (i) from the point of view of data integrity, where we find works that approach our objective pursued only with the design of IoT schemes, with the implementation of Blockchain on hybrid schemes or diversified technologies but concentrated on collecting and distributing information, and (ii) from the point of view of the field of application. Cases are studied with the implementation of technologies in supply chains, value chains, and traceability systems dedicated to data. As can be seen, each sub-level of approach derived from the general points of view contains a description of gaps that motivate us to develop the present work.

It is essential to highlight that the second perspective that enriches the content of

Table 4 can be from any field of application where it is necessary to collect critical use data and certify their collection and transport through the layers of an IoT architecture. With this case study analysis, we only intend to give relevance to the field of food safety where, by far, data management is critical. However, our proposal perfectly applies to health, transportation, logistics, industry, and countless others.

Afterward, we present some security issues regarding architecture and information and some works that pretend to solve them. All proposals focus on IoT, classify security problems, and describe the main security issues in communication within IoT systems [

41].

As long as IoT networks connect heterogeneous low-capacity devices, data collection will present security problems associated with computer networks. For this reason, when designing an IoT network, the level of security that the system will have is also intended. All IoT architectures evaluate their security through parameters such as privacy, integrity, and confidentiality of data.

The transport and application layers of the IoT architecture concentrate most of the proposals on solving information security problems. However, the coverage of these designed measures does not include the end-to-end aspect (from the perception layer to application layer) known as the information transmission path [

22,

42].

Summarized frequent security vulnerabilities in [

43] show the critical IoT security issues. Some of these works focus the analysis on highlighting security challenges and gaps according to a hierarchy as follows: (i) simple security issues refer to everything concerning interfaces and platform authentication, (ii) intermediate security issues refer to device interoperability and authentication within a network, (iii) high-level security issues refer to Internet security and access through software/firmware. Depending on the approach and deployment of Blockchain in an IoT network architecture, it can solve or mitigate the occurrence of critical security issues in IoT ecosystems.

OWASP IoT Top 10 highlights vulnerabilities in web, mobile, and cloud interfaces as those that can affect ecosystems such as BIoTS. Vulnerabilities in IoT networks with extension to cloud processes such as storage or processing warrant focused work to assess the security of their paths and access points [

44].

In the analysis of important security attacks for networks such as BIoTS, message collisions and packet forwarding errors on paths with network intermediaries [

45] are taken into account. However, as in the case of the BIoTS network, cryptographic algorithms are used to protect the flow of information on a given transmission channel.

Sybil attack is a security problem regarding the network nodes that use MAC identification values for access to the IoT platform. These security issues result in a denial of access to legitimate devices on the network. Some solutions proposed using strength measurements of signals for detecting and correcting the attack. In static networks, some works suggest using signals with strength measurements for MAC addresses to detect attacks upon Sybil nodes [

46].

2.1.2. Possible BIoTS Implementation Limitations

In designing, building, and evaluating the device and the BIoTS ecosystem, several possible limitations were found that must be analyzed to be considered a viable option for ensuring data integrity in any field of application. The most important from a technical point of view are listed below:

The energy cost implicit in the deployment of Blockchain technology can be calculated according to the number of nodes implemented (BIoTS sensors). However, in any case, it is not transcendent because the validation of information with the SHA-256 algorithm and with the proof of work (PoW) consensus algorithm is not significant in consumption, given the recurrence of data collection. However, it is good to consider this variable for the network design.

The infrastructure required by the BIoTS ecosystem is more straightforward regarding peripherals because it avoids intermediary devices, and interoperability reduces the use of conditioners and adapter architectures.

The construction of the BIoTS hardware device, as the modules are described in the previous work [

21], generates low economic costs compared to the cost of intermediary devices, adapters, and conditioners. In business terms, the deployment of the BIoTS architecture directly influences the profit since, with the certification of the data, the products and processes are certified.

By the nature of Blockchain technology, scalability problems are ruled out. By the nature of IoT technology, problems of coverage, scope, and the nature of the variables tracked are ruled out. However, each field of application has specific implicit challenges that, in designing the BIoTS ecosystem for a specific field, will have to be analyzed and addressed.

2.1.3. Stakeholder Involvement

The most important contribution of this work concerning stakeholder participation, for example, in a supply chain, is that each stakeholder can have control of a BIoTS node (that of the stage or process of interest). This makes information participation, storage, and validation accessible to all parties involved. It is a cooperative and distributed work that certifies processes and products by certifying individual data in each node. The related papers in the food security systems category in

Table 1 and the supply chain, value chain, and data traceability categories accurately describe the gaps in stakeholder participation in the process, product, and data certification process.

3. Intrusion Detection System (IDS)

The BIoTS ecosystem is evaluated under theoretical criteria, standards, and concepts of the cybersecurity domain. The architecture where the system is deployed needs to be assessed. However, the control plane and some network infrastructure characteristics are involved.

In network, computer, and access security, the concept of AAA (access control, authentication, and auditing) protects data and systems from damage. These concepts support the principles of confidentiality, integrity, and availability in a network. Confidentiality ensures that data are not disclosed, integrity ensures that data remain intact and cannot be modified, and availability guarantees access to data if allowed.

The proposed BIoTS system guarantees access control with the policies of the software component of the configured Blockchain network. Additionally, access control is guaranteed from the VPN (virtual private network) created to deploy the system evaluation. User authentication is subject to the Blockchain network’s characteristics, with asymmetric cryptography, consensus, and cryptographic algorithms.

3.1. Features of BIoTS Network Based on IDS

Pros: Networks tapped by an IDS can be evaluated on multiple nodes, a single node, or on devices, subjecting them to data traffic overload. BIoTS network devices are mostly passive devices prone to direct attacks against network performance.

Cons: The IDS implemented in BIoTS may require additional network configurations depending on the service provider and the type of security it has by default. Sometimes these limitations may mean that traffic cannot be monitored or analyzed. For this reason, injected security attacks must be performed under this premise. It also cannot report on whether attack attempts succeed or fail. Therefore, network-based IDSs require some active, manual involvement by network administrators to assess the effects of reported attacks on encrypted networks.

3.2. Technical Considerations of the Security Assessment Ecosystem

The BIoTS network access control determines the testing and injection of security attacks necessary to evaluate the information transmission path proposed in this work, which passes through the three layers of the BIoTS architecture. The three possible network access types depend on the devices, resources, and deployment of technologies. There are three types: MAC (mandatory access control), DAC (discretionary access control), and RBAC (role-based access control). Based on transferability, discretionality, and controllability considerations, the BIoTS network is assumed to have DAC access control. The nature of the database distribution throughout the network, the delegation of access and participation permissions, and the operating system that governs the system allow it to be identified.

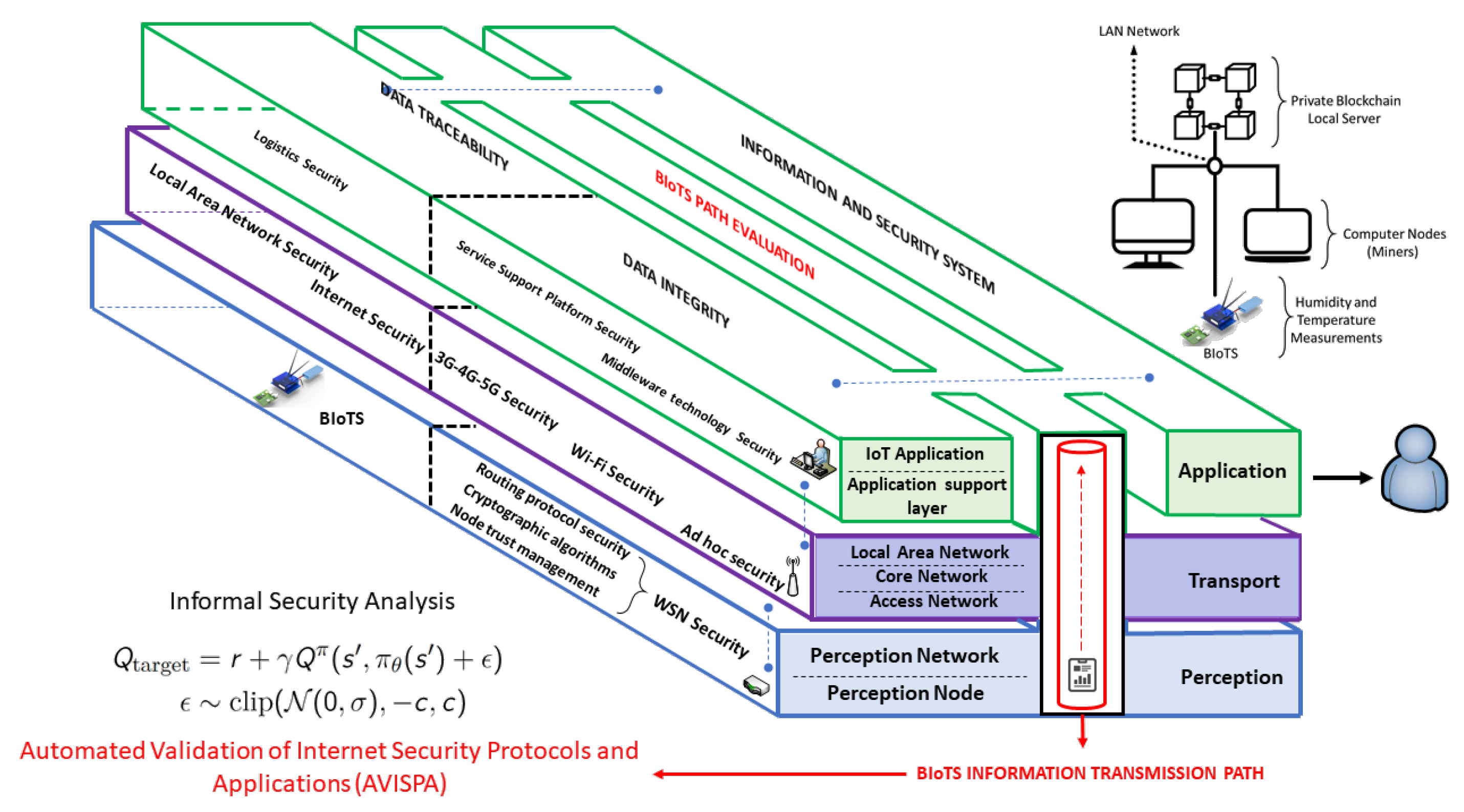

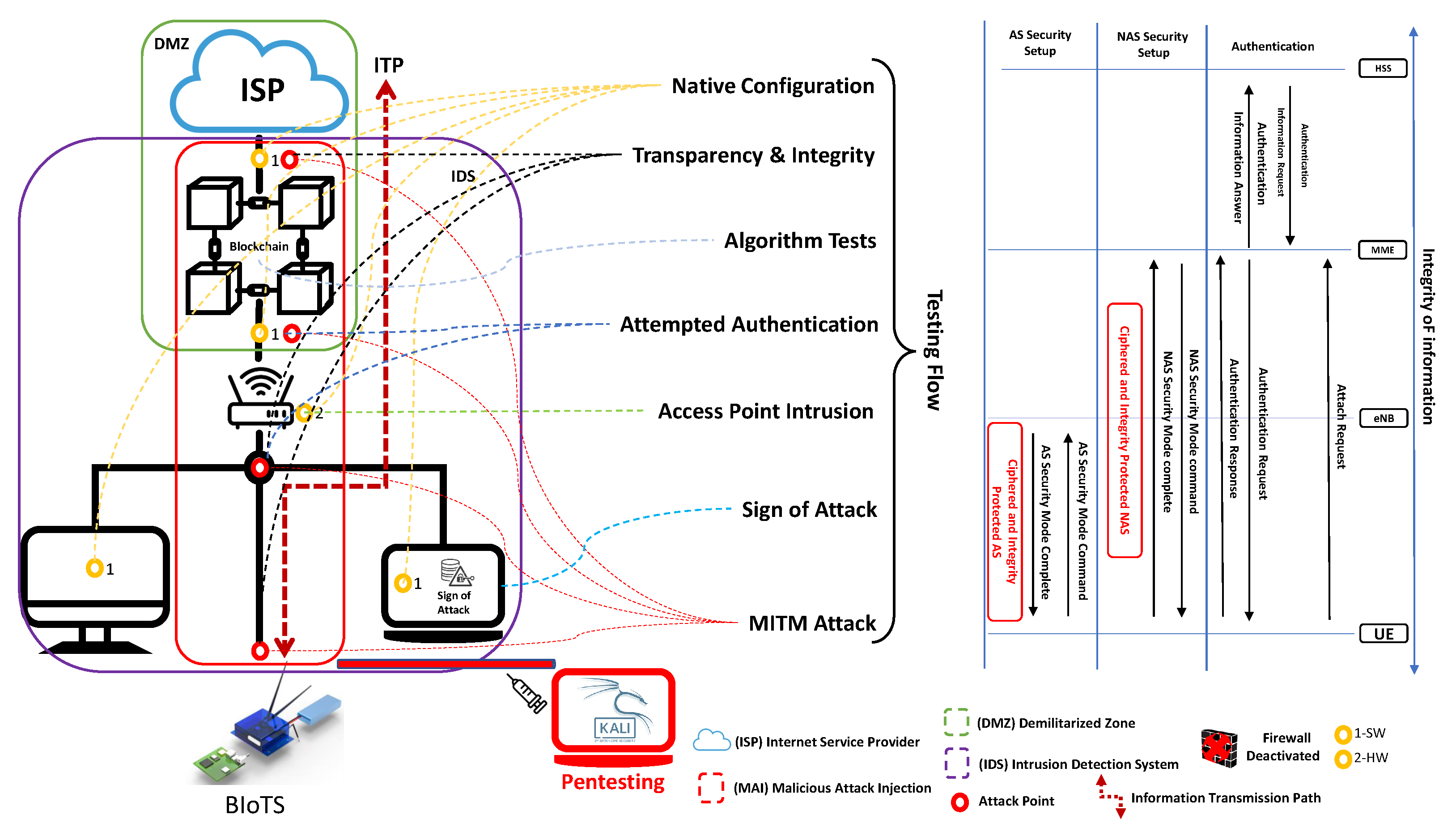

Figure 6 describes the technical and architectural configuration of the security testing ecosystem. As can be seen, in the application layer of the architecture, a private Blockchain network is deployed with three participating nodes (two computers and a BIoTS sensor) directed to an access point access node (upper right corner). In this network, the values proposed as a transaction by each node will be validated with the help of the network consensus algorithms. As this communication action suggests modifications or regulations in the network, they are described in layers in the image.

Authentication in the BIoTS network has two characteristics. (I) In the WLAN network, only three devices are configured (two computers and the BIoTS device) through the IP address (Internet protocol). (II) The authentication is performed through the consensus algorithm and cryptography within the Blockchain network operation. In this way, the authentication in the BIoTS network is guaranteed and will also determine the type of intrusion detection system.

The goal of auditing is to restore the data integrity of a network or system. The audit is obtained thanks to the property of the Blockchain network to distribute the database throughout the network. In this log-in, we can track events, errors, authentication, and access attempts. The objective of obtaining this data type is to develop a path to define better security policies and rules that will allow for a subsequent judicial investigation to collect evidentiary material.

The main objective of this work is to certify processes and products in a production process (food traceability system) by evaluating the integrity of the data transported along the information transmission path within a Blockchain–IoT-based architecture. Thus, the characteristics of the BIoTS system promote, from every point of view, the digital validation of identity and the verification of created, distributed, or stored information. Access control and authentication in cryptography-based systems already guarantee much of the certification. However, implementing security protocols based on authentication or those that are part of the public key infrastructure (PKI), used as a plan or as a method for exchanging information authenticated and protecting such data, can ensure the integrity and transparency of data within a network. Therefore, we sought to immerse the BIoTS device and the designed network in a security intrusion testing system that contains a security attack injection mechanism to validate the proposed path.

The BIoTS ecosystem is configured over a WLAN network. This deployment of 802.11 wireless LAN nature is based on the wireless equivalent privacy (WEP) protocol and needs to be regulated for successful security attacks and evaluation. Although these protocols are useful in the normal operation of the network in terms of authentication, for this experiment, they can prevent vulnerabilities that we precisely want to evaluate with BIoTS.

3.3. Vulnerability Scanning

This system’s design involves tools to identify potential problems that could lead to a security breach. The method may have the ability to test the strength and compliance of password policies, measure the ability to access networks from an outside network, provide analysis of known security vulnerabilities in NOS or hardware devices, or test the responses of a system in various scenarios that could lead to a denial of service (DoS) or other problems such as system downtime.

This system allows us to evaluate the performance of the BIoTS device through network monitoring. In the case of this proposal, the scanning system will be provided with the following features:

Scanning of security vulnerabilities in an information transmission path.

Analysis of security vulnerabilities in hardware devices.

Evaluation of system responses to an attack scenario.

Security Attacks (Test Design—Data Integrity Attacks)

The design and injection of security attacks in the BIoTS network have several implicit challenges. Various methods for launching security attacks depend on the intended target (data integrity attacks). However, as we see below, authentication will also be considered a security attack target. There are three categories into which attack methods can be grouped:

By the general objective (integrity assessment) and particular objective of the attack (application layer, BIoTS network, or combination).

By the type of attack with harmful intrusion or observation and analysis (active or passive).

By the nature of the attack (corruption of passwords, cryptographic algorithms, hardware devices).

This categorization becomes complex given the nature of the BIoTS ecosystem since, in this case, we have an application and network-based architecture. Active attacks such as man-in-the-middle (MITM), cryptographic attacks, software exploitation, and mathematical attacks are used. In addition, other attacks, such as DDoS (distributed denial of service) and buffer overflow, directly affect the state of the data moving along an information transmission path. Therefore, they are combined and somewhat sophisticated attacks.

Man-in-the-middle and data modification are the security attacks that will be the focus of the BIoTS security assessment. The best example of this attack is known as SSHMITM. This attack acts against SSH security, intercepting information from the client and attempting to replicate the response from a fake server to the server where the application is hosted. This attack is identified and traced (vectorized and sample traces) and is the only one from which technical samples of network behavior are taken.

Figure 7 summarizes the security attacks’ logic, order, and configuration in the BIoTS ecosystem security assessment scenario. The left part of the figure represents the network layout in three zones (purple, red, and green): (I) the intrusion detection system (IDS) purple zone, with the center at the router from where it detaches the nodes and routes the information to the Blockchain hosted on the local server; (II) the red zone and dotted red line information transmission path (ITP), which is the zone that will be subject to monitoring and data acquisition concerning security attacks against the integrity of the data conducted over this channel; (III) the green zone, which is the demilitarized zone (DMZ) configured from the ISP (firewalls, firewalls, and active intrusion protection are eliminated). This zone is configured in a primitive way to make the exercise of concentrated security attacks possible. In the middle of the figure, we can observe the list of the security test flows from the native configuration of the Internet service in the upper part to the attack injection in the lower part (the penetration test is conducted from Kali Linux). Finally, on the right side of the figure, we find the sequence diagram for security procedures discriminated by stages and layers of the BIoTS architecture. In the vertical line that seeks data integrity, we see in the limits: UE: user equipment, eNB: evolved node B, MME: mobility management entity, and HSS: home subscriber server [

47].

This paper will not address the security issues of Blockchain technology because these are widely tested and analyzed. However, transmitted packets are analyzed to evaluate the potential for attacks such as brute force attacks in the BIoTS ecosystem. The tools also detect the potential risk in the Windows operating systems that govern the BIoTS network. Still, they need to be analyzed in depth because they do not influence the integrity of the data along the information transmission path proposed in this work.

It is considered a passive attack to capture information but not attack the integrity of the data. Sniffing and eavesdropping are also identified by scanning tools on transmission paths and access points to application and hardware devices.

3.4. Testing Ecosystem

The BIoTS network is based on wireless communication technology. For this reason, scanning vulnerabilities in the system and the injected security attacks will have typical orientations of the physical devices, the network configuration, the operating system that governs it, and the adaptability of the cybersecurity tools used in the test ecosystem.

Due to the nature of the Blockchain technology (based on cryptography) deployed in the BIoTS ecosystem, specific security attacks related to authentication and information transport, such as TCP/IP hijacking, replay attacks, spoofing, SYN attacks, or war dialing, are impossible. However, as the BIoTS network has been manipulated to unbundle security elements implemented by the Internet service provider, it has the configuration of an internal and transparent private primitive network. The Windows operating system will govern the network, and the monitoring deployment makes the ecosystem acquire variables of complexity and vulnerability in the access and connection points throughout the network. These elements will then determine the configurable elements of the test ecosystem. In this case, the tool (Kali Linux) will be used.

As stated above, the BIoTS network is WEP; therefore, the security attack must concentrate on access points, edges, or boundaries along the entire architecture. These access nodes are the sensor, the router, and the application.

3.5. Security Topologies

The local-network-configured BIoTS has a computer (laptop) of the network as its deployment center. This computer runs with the Windows operating system and hosts the Blockchain server. For this reason, it is necessary to configure the firewall deactivation at two network points: (I) in the computer from where the network and the server are deployed, and (II) in the router (AP) that provides the service. This configuration is software. However, the deactivation of the AP firewall is carried out from the external distribution point and has some hardware implications. The latter arrangement is requested from the service provider.

The classification of IDSs varies according to the activity: they can be traffic, supervisory, or transaction IDSs. Therefore, since we want to evaluate elements of network traffic, it is necessary to distinguish whether our IDS is network-based, host-based, or application-based. The IDS applied to BIoTS is network-based and application-based since we are interested in evaluating the integrity of data moving bidirectionally along a network path.

The reason why the IDS is a hybrid is that network and application IDSs have characteristics that make them complementary for this evaluation. Some of these characteristics will be described below.

4. Results

Wireless networks have wide vulnerabilities due to the nature of transmission since there is no restriction on the coverage space, and scanning is easy for external agents. Technically and scientifically, extensive vulnerabilities have been discovered in WAP and WEP-type networks. They will not be described here, nor will the attacks be so oriented, given the complexity of the analysis. However, we will concentrate on the most common attack that jeopardizes the integrity of transmitted data.

In the case of our experiment, we can simulate a rogue access point in the range line of the wireless network. This access will allow us to reach the edge of the BIoTS device and the application layer with the MITM attack. This type of intrusion is effective for the experiment in question. This way, we will test the vulnerability to this attack more specifically since the BIoTS network will always be deployed in wireless networks.

4.1. MITM Attacks on Wireless Networks

Spoofing is a security challenge in wireless networks. The user can be spoofed if the hacker obtains the network node’s MAC address and IP address information. While the data can be copied, by the nature of the BIoTS network, it can resist this type of attack. However, it will be checked with basic tests.

Hackers in wireless network APs such as hubs and routers often use sniffing and eavesdropping. Although in encrypted communication, it is unlikely to alter the data (integrity), it is possible to monitor the network activity and obtain the information and decode it by brute force processing (in this case, it is straightforward given the size of the network (three nodes)).

The injection of MITM attacks to BIoTS describes the behavior of the network in the face of the imminent hijacking and modification of information. As network and security administrators, we are able to identify the intent and attack or legitimacy of the traffic.

We also act as network hijackers with the use of the Kali Linux tool from which we will be able to view and interfere with physical network devices. The intervention of TCP/IP packets passing through the routers or AP provides us with the local addresses and, with them, the transported information. It is important that the source and destination are tracked in the anomaly analysis.

The source and destination table of information packets record the local MACs of the device and become dynamic depending on the information flow and network variation. In our case, BIoTS participation is constant; therefore, the table becomes static and easier to read to identify attacks. As these attack tests do not provide vectors or data sequence traces, these BIoTS network security tests will only have statistical probability evaluation by mathematical analysis.

Data integrity can also be attacked by the application deployed on the web; in the case of the BIoTS system, this aspect will not be evaluated, and probability tests will not be considered since server security is beyond the scope of this work.

From the point of view of the (physical) devices dedicated to security in the BIoTS network and due to the network’s typology, only the router (firewall) configuration will be considered to deploy the security tests.

4.2. IDS Features Based on Applications

Pros: This application-based IDS focuses on scanning nodes, edges, or borders within an architecture where a specific application runs. The BIoTS information transmission path carries data that are subject to intrusion theft or modification. The IDS designed for BIoTS can track unauthorized activity and work with encrypted data, as is the case with the SHA-256 algorithm.

Cons: Sometimes, application-based IDs are more vulnerable than host-based IDs given the physical access points available.

As the IDS implemented in the BIoTS ecosystem has an integrity assessment approach on a specific network path, signature detection was implemented, consisting of a database that stores data characteristics, patterns, and/or activity related to known attacks. This database serves as a reference to compare and assimilate the data recorded in the current flow. This process is known as signature detection and we use it to identify MITMs in the information transmission path in the BIoTS ecosystem. The rules designed for comparison are what make it possible for certain traffic to be marked as normal or abnormal and to be counted in the statistics.

The IDS in BIoTS is configured to monitor access points, hostile activity, and known intruders. Typically, these systems are triggered by comparing network activity against a database of attack signatures. An alert is raised and logged for future reference if a match occurs.

The most important characteristic of signatures and with which we identify attacks is the profile that is generated when the data are marked as malicious, defective, or intrusive. These characteristics are usually emulated to facilitate entry into the information channel. However, in the BIoTS network, the IDS will emulate intrusion attempts as realistically and maliciously as possible. Most of the signatures created in the BIoTS IDS were built by running an exploit emulating the real and clean network traffic several times. In this way, we were able to effectively inject attacks for the purpose of data integrity assessment within the data transmission path.

Configuring network devices (such as BIoTS, laptops, and routers) with the modified installation configuration for BIoTS leaves the system critically vulnerable. Ideally, it would be best to test and secure the configurations before activating the devices on the network. However, the basic arrangements of the physical devices do not allow this. They are set for convenience and not for control and security (two computers with Windows OS and the BIoTS sensor). A simple configuration is made from the Windows device that deploys the Blockchain only with default settings, but to the detriment of security. In our case, it will open the door to an attack against integrity on a specific path.

4.3. Technical Characterization of the BIoTS Network for an Integrity Attack

Data transport in the BIoTS network is performed using cryptographic encryption executed by the SHA-256 algorithm. This Blockchain power for the encryption of the transmitted data prevents intrusion in the transport. A cryptographic and consensus algorithm in a Blockchain network is a set of instructions to prevent tampering and ensure security in the data domain. For this reason, the encryption and decryption of this information will influence the results of both the success of the attack and the evaluation of the attacked route.

In the case of the BIoTS network, the algorithms impose an additional challenge in the nature of the security attack and its detection. The blocks generated by the transactions cannot discriminate if the data have been corrupted; for this reason, this work projects a contribution in that aspect of limit or edge of the application.

Cryptography and consensus using Blockchain is a way to guarantee integrity. The asymmetry in encryption and decryption and the use of public and private keys make our experiment an opportunity for validation through digital signatures based on security analysis of attacks against data integrity in a Blockchain network. The MITM attack in the BIoTS ecosystem reassigns importance to the edges or borders of an ecosystem based on these technologies.

It may be that some asymmetric algorithms such as SHA-256 are immune to MITM attacks. However, when a third party intercepts the data and the route in general, if carried out with the appropriate technique, it will be entering through the weakest link in the communication lines between the participating nodes, and from there to the application layer.

Asymmetric cryptography can authenticate a sender by their private key, assuming it is kept confidential. Since each person is responsible for their private key, only they can decrypt messages encrypted with their public key. Similarly, only those persons can sign with their private key messages validated with their public key. Thus, in addition to the MITM attack to which the BIoTS system is prone, there is also an authentication attack. BIoTS is then prone to man-in-the-middle attacks on information transport and user or distributed network participant authentication.

4.4. Security Metrics Calculation

Next, we describe the security assessment model in terms of the probability of occurrence in the BIoTS network, the subnetwork (nodes: laptops and sensors), and the vulnerabilities described in the previous section. The BIoTS network indicators are (i) a subnetwork S (sensor and laptops), (ii) a set of IoT nodes N (three; specifically, two laptops and one BIoTS sensor), and (iii) a set of vulnerabilities V. In notation, we determine a subnetwork as

, a node as

, and a vulnerability as

. The goal of the penetration test is to find one or more attack routes to tap the network through one or more entry points. Therefore, we consider a set of all AP attack paths to achieve data integrity corruption. The information transmission path

has three access or edge nodes where the attacks are printed. The nodes, depending on their location in the ecosystem, have various vulnerabilities calculated here. The definition of the mathematical notation used is described in

Table 5.

The attributes of the BIoTS network are . Each subnetwork has a name and a set of BIoTS network nodes . Each node has a name , a type , an information mobility , a set of vulnerabilities , and a set of security metrics . Each vulnerability has a name and a set of security metrics .

Probability of attack success: the attack success probability measures the probability of an attacker achieving the attack target. At the nodes, the metric shows the probability of success of the attack on a node. First, the probability of success of the attack on the BIoTS sensor node and the laptop nodes immersed in the BIoTs network is calculated using Equation (

1). Then, we calculate the attack success probability at a node

by Equation (

2). And finally, at the path level, the metric is the probability of an attack compromising the channel through the attack path and is calculated by Equation (

3). For terminology and logical assignment reasons, an AND relationship is established for selecting nodes to attack and evaluate (see

Figure 8).

Attack impact: The damage caused by an attack on a node generates the impact values of the attack on that node. They are recorded in the attack list, and each node

in the network is calculated using Equations (

4) and (

5). In the network paths (Una), the measure is the damage caused and the successful intrusion to compromise the BIoTS device through the information transmission path. The value of the impact of the attack on the attack path (BIoTS) is calculated by Equation (

6). At the network level, the measure is the maximum loss caused by an attack to compromise the BIoTS device among the three possible paths. The AIM value at the network level is given by Equation (

7).

4.5. A MITM Attack in a BIoTS Network

The attack against BIoTS is directed at all three network paths, with a specific concentration on the BIoTS sensor path. Once the connection node of this sensor is identified, we make the attack compromise the consensus algorithm of the Blockchain network according to MITM attacks [

48].

The attacker can remotely compromise the BIoTS network to tap information that is transmitted over the information transmission path. Several papers in the literature address remote attacks of this type [

38,

42,

49,

50]. According to the practical proofs of concept in the articles, attackers remotely tap information transmitted in a distant wireless network. Subsequently, they can use it as full access to exploit network vulnerabilities as shown in

Figure 8.

Based on the vulnerabilities described in

Section 4.4, we make assumptions about the metric values of the vulnerabilities in the BIoTS network and show the values in

Table 6. The table presents the vulnerabilities in the network’s three nodes and displays the metrics assignment for attack success probability and impact. The compromise rate indicates how often the vulnerability can be successfully exploited. As node 2 (n2) contains the BIoTS sensor, this information transmission path is the target of the attack and monitoring (

).

It is necessary to identify the attack paths and decide which devices—in this case, the BIoTS sensor—are included in the MITM attack. Risks are measured according to the evaluation of IDS metrics and algorithms.

We estimate the vulnerability information of node 2, where the BIoTS sensor is located. We reconstruct the IoT network using the IoT generator to calculate the metric values after injecting the MITM attack. The results of the security vulnerability analysis calculations are shown in

Table 6.

In Algorithm 1, we use the reliability graph model in the SHARPE (Symbolic Hierarchical Automated Reliability and Performance Evaluator (Version 2001-MS-DOS PROMPT for WINDOWS and LINUX.)) software package [

51] to calculate the probability that there is or is not a vulnerability in the information transmission path from the attacker (Kali-pen-testing tool) to the target (sensor BIoTS). After the execution of the network model, we run one minus that probability to calculate ASP with Equation (

3).

| Algorithm 1: Calculation of ASP |

Data: AP ← and (n ∈ ap) ▹ Define variable to answer Result: ASP Construct a direct graph with node set H for each attack path (n1, … , n3) ∈ AP do for each i do include edge with value in graph end for end for ASP ← Calculate Probability(graph)

|

At the node level, the metric values show that the BIoTS node attack has a lower probability of success, and lower cost, but a lower impact than attacking another node. Therefore, the attacker is likelier to choose computer nodes as an entry point. However, these nodes must be protected to prevent the attacker from entering the network. For defense,

decreases (see Equation (

8)), which means that encryption and a direct channel with no intermediary strategies effectively reduce the probability of attack success and extend the mean time to compromise. At the same time,

does not change since the impact values of nodes 1 and 2 are the same (see Equation (

9)).

For

(see Equation (

10)), since tapping node 3 (n3) requires a lower cost than tapping node 2 (n2), deploying defense is more costly for the attacker. For

(see

Table 7), since tapping node 3 (n3) has a higher probability of success than tapping node 2 (n2), deploying defense decreases the likelihood of success of the attack. In our case, we do not deploy any network defense strategy as it causes a lower probability of attack success and a higher cost for the attacker. Since each sensor has only one vulnerability, we calculate

using Equation (

2). We also estimate

and

using Equation (

3). ASP2 is calculated using Algorithm 1, where the SHARPE result is 0.11 and 0.70 (see

Table 7 and

Table 8).

does not change since the metric values do not change after the attack. Thus, we can observe that without protecting the BIoTS sensor node, it is more effective than safeguarding any of the other two nodes (see Equation (

11)).

5. Conclusions

Designing the BIoTS network and assessing the security of an information transmission path have implicit challenges regarding technical configuration and algorithmic and architectural logic. For this reason, modeling security to calculate the probability of success of computer security attacks, such as MITM in networks and systems based on IoT–Blockchain, is critical in application fields such as food traceability. This evaluation allows for certifying data obtained from the sensing layer, through the transport layer, and up to the application layer in the IoT architecture.

This article presents the architectural configuration of the BIoTS (sensor and system) evaluation ecosystem to characterize heterogeneous devices facing security threats: (i) the information collected from the BIoTS network behavior is processed, (ii) an IDS (intrusion detection system) is configured and deployed, (iii) a network security analysis and visualization is performed, and (iv) a mathematical modeling of the vulnerability of an information transmission path in the network is performed.

From the analysis results, the information transport route proposed by the BIoTS sensor effectively safeguards the integrity of the data transmitted over the channel. The information transmission path of the BIoTS device is less prone to data integrity security attacks (MITM) than other devices in the network.

The implemented concept of the BIoTS ecosystem, which acts as a dedicated device with specific hybrid architectural features of Blockchain and IoT technologies, has the proven guarantee to work for any field in which the use of data is a critical issue. For this reason, interesting future work is to deploy a network of nodes with BIoTS devices and generate the validation of data suitable for certification from any node or stakeholder involved in the application field disseminated by stages or processes.

A cybersecurity-assessed architecture that enables point-to-point data certification in an information transmission path requires less logistical and technical effort to deploy than an independent Blockchain and IoT network design but is adapted to work together. For this reason, it is concluded that adapting architectures is practical and mitigates implementation and development difficulties.