1. Introduction

A structured method is employed in programming and software development in software engineering to enhance quality, time, and budget efficiency, including guaranteeing a structured software system [

1,

2,

3]. The software procedure, similarly, recognized as the software method, is a series of organized activities that result in software conception. These tasks could comprise developing software from scratch or modifying a prevailing one [

4]. The following actions must be included in any software development process. The first is the software specification, which outlines the program’s core functionality and the limitations surrounding them. The second step is to design and create the software. Third, software verification and validation: the program must fulfill client requirements and correspond to its specifications. Finally, software evolution and maintenance involve changing the program to suit changing consumer and market desires [

5]. They include sub-events, such as requirement authentication, architectural strategy, testing, and supportive events, such as configuration and modification administration, quality guarantee, and project administration [

6,

7,

8]. Other actions involve providing new technological tools, following best practices, and standardizing processes. A process, therefore, comprises the development description, which contains the following products: pre- and post-condition: the condition must be factual before and after the activity, the result of an action, and roles: the duties of the persons participating in the process [

4].

A software flaw is any error or defectiveness in a software product or software development (SD), often known as a fault or bug [

9,

10,

11]. Software defect prediction is one of the most practical tasks in the testing process, which recognizes the segments that are problem-predisposed to and need rigorous testing [

12,

13,

14]. This allows experiment resources to be utilized more effectively while adhering to restrictions. Software defect prediction is beneficial during testing since it is not always possible to foresee the problem modules. Various difficulties, as well as the usage of faulty prediction models, obstruct smooth functioning [

15,

16,

17].

It is essential to determine the software’s defectiveness to organize testing operations since it is conceivable to concentrate further on the flaw-prone modules with the most mistakes. As a result, the testing process takes less time and effort, and the project’s overall cost is reduced [

18,

19]. Software defect prediction models aim to forecast quality aspects, such as whether an element is susceptible to failure. Approaches for detecting flaw-prone software elements aid resource preparation and development, including cost elusion via efficient authentication [

20,

21]. These approaches may be employed to forecast the response variable: a module’s class (e.g., flaw-prone or non-flaw-prone) or a quality factor (e.g., the number of flaws). To forecast software flaws, statistical tools, machine learning (ML) methods, and soft computing procedures are often utilized [

22,

23,

24,

25].

As a classification task, SDP may be considered as a supervised binary classification delinquent [

26]. Software segments are labeled as faulty or non-defective and are represented by software metrics [

27,

28,

29]. To train flaw analysts, historical data tables are created with one column containing a Boolean value for “flaws found” (i.e., reliant variable) and other columns describing software features concerning software measurement (i.e., independent variables) [

30]. Grounded on a training set of data encompassing occurrence (or instances) whose class membership is recognized, binary classification in machine learning identifies which set of classes (sub-populations) a novel remark fits into [

31]. Therefore, this research proposes the deployment of dagging meta-learner on classification algorithms for SDP processes. An experiment was designed to examine the efficacy of dagging-based SDP models for identifying software defects. Dagging-based and baseline classifiers, including NB, DT, and kNN, were utilized on nine NASA datasets. The following is the contribution of the study:

Deployment of dagging meta-learners on classification algorithms.

Dagging-based and baseline classifiers, such as NB, DT, and kNN were applied to nine NASA datasets.

Use of an AUC, F-measure, and PRC value for system evaluation.

The remaining sections of this article are structured as follows:

Section 2 offered the related literature on defect predictors that researchers have examined.

Section 3 discussed the proposed system and the evaluation carried out to check the system’s performance. The result obtained from the implementation and discussion on the results is presented in

Section 4.

Section 5 concludes the article and suggests upcoming works.

2. Related Works

Machine learning and deep learning have been used in different domains for optimization, scheduling, etc. [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Even though several defect prognosticators exist in the literature, few comprehensive benchmarking studies exist. Comparing the defect predictors’ accuracy is crucial since the findings of one technique are seldom consistent across multiple datasets [

36]. This is due to several factors. First, early defect prediction research relied on a limited number of datasets. Furthermore, since the performance metrics employed in each study differed, comparing them was challenging. Consequently, thorough benchmarking studies are usually appreciated to determine which defect prediction approaches offer the most accurate results.

In their study, Xie et al. [

37] use a multi-granularity neighbor residual network (MGNRN) to create an anomaly detection strategy for time-series data. They first establish a neighbor-based input matrix by considering multi-granularity neighborhood characteristics and build a neighbor input vector with a sliding time window for each data sample. Second, they use multi-granularity time windows to calculate the sample’s linear and nonlinear neighbor characteristics. Finally, they anticipate the sample’s anomalous probability by combining the linear neighborhood residual with the nonlinear residual. The precision and F1-metrics demonstrate the multi-granularity neighbor residual network’s efficacy in improving the accuracy of anomalous detection, and the experiments support these claims.

Khurma et al. [

38] proposed an island BMFO (IsBMFO) model. They presented an efficient binary form of MFO (BMFO). IsBMFO separates the population’s solutions into islands, which are sub-populations. Each island is handled separately with a BMFO version. After a specific sum of iterations, a migration step was carried out to trade solutions across islands, increasing the algorithm’s diversity power. The suggested strategy was evaluated using twenty-one publicly available software datasets. The trials indicated that employing IsBMFO as feature selection (FS) enhances the classification results. With an average G-mean of 78 percent, IsBMFO with SVM was deduced to be the best model for the SDP issue among the further analyzed techniques.

In a stringent CPDP environment, Malhotra, Khan, and Khera [

39] developed a testing approach based on six distinct neural networks (NNs) on a dataset, including 20 softwares from the PROMISE repository. The optimum design was then compared with three suggested CPDP approaches that span a wide variety of circumstances. They discovered that the modest NN with dropout layers (NN-SD) was accomplished superlatively and statistically considered superior to the CPDP approaches when compared with other approaches throughout their investigation. The AUC for receiver operating characteristics (ROC) was employed as the performance measure. The Friedman chi-squared and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to assess statistical implications.

To lower the impact of the class imbalance dataset, Jin [

40] developed a unique distance-measure learning built on cost-sensitive learning (CSL), which is used with the large distribution machine (LDM) to replace the standard kernel function. Furthermore, the enhancement and enrichment of LDM based on CSL were investigated, with the improved LDM serving as the SDP model, dubbed CS-ILDM. The projected CS-ILDM was then employed with five publicly accessible datasets from NASA’s Metrics Data Program repository (NASA MDPR), and its performance is similar to that of competing SDP approaches. The experimental findings show that the suggested CS-ILDM has high recognition performance, can lower the misprediction rate, and eliminate the influence of sample class imbalance.

Wang et al. [

41] proposed an SDP system built on LASSO-SVM. The issue of most SDP models having low prediction accuracy was discussed in their work. A support vector machine technique and a least absolute value compression (LAVC), and a selection process are combined in an SDP model. First, the FS capability of the LAVC and selection technique was employed to minimize the dimension of the original dataset and non-SDP data were deleted. Then, utilizing the constraint optimization capability of the cross-validation technique, the optimum SVM value was determined. SVM’s nonlinear computing capability completed the SDP. The recall rate was 78.04 percent, and the F-metric was 72.72 percent. The accuracy of simulation results was 93.25 percent and 66.67 percent. The findings revealed that the suggested defect prediction model outperforms the classic defect prediction model’s prediction accuracy and speed.

Kumar and Shankar [

42] created a Mamdani fuzzy logic-based software defect prediction model that predicted software faults using classic membership functions (Triangular, Trapezoidal, etc.) and a domain expert’s unique membership function. They used a basic Takagi–Sugeno model to enhance the Mamdani system and achieve better results. The plan assessed fuzzy logic models using standard regression models, such as multiple linear regression and random forest regression.

Akintola et al. [

43] considered the impact of filter FS (FFS) on SDP classifiers. Ten NASA datasets (MW1, MC1, MC2, PC1, PC2, PC3, PC4, KC1, KC2, KC3), FFS algorithms including principal component analysis (PCA), filter subset evaluation (FSE), and correlation feature selection (CFF) subset evaluation including machine learning (ML) classification algorithms, such as NB, DT J48, MLP, and kNN were categorized using classifiers that had been carefully chosen based on their properties. According to their findings, feature selection methods can improve the performance of learning algorithms in SDP by eliminating immaterial or redundant features from the data ahead of the classification procedure. Nonetheless, the limitation of this study is that they only looked at filter-based feature selection, which is not the only type of feature selection.

Ranveer and Hiray [

44] summarized malware detection (MD) methods founded on the stationary, active, and hybrid executable investigation. A comparative analysis of characteristics was offered, illuminating their impact on the system’s performance. They discovered that using a suitable feature extraction strategy may result in high accuracy and an actual positive rate (TPR). Although op-code and portable executable (PE) capabilities improve the speed and accuracy of a malware detection system, false positives are still a problem. The suggested malware categorization algorithms should be able to cope with many daily new malware variants while maintaining system performance and accuracy in real time. However, the authors did not explore FS methods since the feature extraction technique would have changed the dataset’s depiction.

Laradji et al. [

45] explored multiple FS strategies for SDP. They found that picking a few high-quality features resulted in a substantially better AUC than using a more significant number of features. They similarly demonstrated the effectiveness of ensemble learning (EL) on datasets with unbalanced duplicated features. They suggested the utilization of a two-variant EL classifier. Experiments on six datasets revealed that greedy forward selection (GFS) significantly performed better than correlation-based forward (CBF) selection.

Additionally, we showed the efficacy of utilizing an average probability ensemble (APE) made up of seven properly designed learners, which outperformed traditional approaches, such as weighted SVMs and RF. Finally, the improved form of the suggested method, which coupled APE with GFS, achieved better AUC values for all datasets, which were near 1.0 in the case of the MC1, PC4, and PC2 datasets. However, for feature selection, the researchers only evaluated GFS and CBF, which is insufficient for a universal outcome.

He et al. [

46] published empirical research on how a prognosticator founded on a reduced measured set was created and utilized for both with-in-project defect prediction (WPDP) and cross-project defect prediction (CPDP). The findings showed that the prognosticator created with a reduced measured set functioned well and that the suggested predictor and other benchmark predictors had no significant differences. The minimal metric subset was considered excellent based on the unique criteria for complexity, generalization, and accuracy since it may deliver good results in various circumstances and was independent of classifiers. In conclusion, their findings demonstrated that a more straightforward measure proposed for flaw forecast is realistic and valuable. A forecasting method built using a minimal subset of software measurement may deliver acceptable results. The investigators solely looked at feature selection filter approaches, with wrapper and hybrid FS being shown to be superior to the filter technique. The summary of the related works is shown in

Table 1.

From the literature reviews discussed above, it is evident that several researchers have proposed and developed many approaches and techniques for SDP. Many have used techniques, such as ML, DM, etc. Many of these researches have low accuracy, precision, F-measure, and AUC ROC values. It was also discovered that many researchers did not even evaluate performance measures, such as AUC ROC values and F-measures. However, there is a continuous and imperative need to research and develop more accurate and sophisticated SDP models or methods, which led to the motivation behind this proposed study. In this study, we proposed the use of four performance measures to evaluate the system performance: Classification accuracy, precision, F-measure, and AUC ROC values.

3. Materials and Methods

This section discusses materials, like datasets, and methods, such as algorithms. This suggested system aims to examine and evaluate the impact of various wrapper feature selections (way of feature selection) on classifier performance for software fault detection. Decision tree (J48), naïve Bayes (NB), and k-nearest neighbor are the classifiers (kNN). All algorithms will be implemented by creating a route to the WEKA (Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis) API in the Eclipse IDE. Eclipse software was used to implement the method in this study. The experiment compares single classifiers versus dagging-based classifiers for software fault prediction using ANP. The datasets and experimental design are presented in this section. Nine public-domain software fault datasets were collected from NASA’s MDP repository for this investigation. These nine public domain faults are PC1, PC3, PC4, PC5, CM1, KC1, KC3, MC2, and MW1. Each dataset was analyzed using 10-fold cross-validation, in which the dataset was divided into ten subsets, nine of which were used to train the classifier, and one subset was used to test the model generated by the classifier. A classifier’s efficiency may be measured in a variety of ways. Accuracy, the area under the curve (AUC), and F-measure scores will all be assessed in this investigation [

47]. The NASA MDP dataset used for the experimental analysis in this study was obtained from NASA MDP software defect datasets (

figshare.com. Accessed on 17 June 2021).

3.1. Data Description

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Facility Metrics Data Program (MDP) repository contributed nine public-domain software defect datasets for this investigation. The following are short summaries of the MDP datasets, and the dataset attributes description is shown in

Table 2.

PC1: This collection contains flight software from a decommissioned earth-orbiting satellite. It comprises 40 kilobytes of C code, 1107 modules, and 22 characteristics.

PC2: This dataset comes from flight software from a decommissioned earth-orbiting spacecraft. It comprises 40 kilobytes of C code, 1107 modules, and 22 characteristics.

PC3: This collection contains flight software from a presently active earth-orbiting satellite. It includes 1563 instances and 40 KLOC of C code.

PC4: This collection contains flight software from a presently active earth-orbiting satellite. It has 36 kilobytes of C code and 1458 modules.

CM1: This dataset comes from a research tool with around 20 kilo-source lines of code written in C code (KLOC). Overall, there are 498 occurrences and 22 characteristics.

MC2: This dataset has 161 occurrences and 40 characteristics.

MW1: This dataset is approximately a zero-gravity combustion research developed in C code with 8 KLOC and 403 modules.

KC1: This dataset comprises a C++-based stowage administration system for achieving and handing out data. Overall, there are 2109 instances and 22 characteristics.

KC3: This dataset is approximately the satellite metadata group, handing out, and dissemination. There are 458 instances and the it is inscribed in Java with 18 KLOC, 40 characteristics, and 18 KLOC.

3.2. Proposed Models Implemented

Three classifiers were proposed in this study, and they include naïve Bayes (NB), decision tree (DT), and k-nearest neighbor (kNN). They are popular machine learning algorithms used in various domains, including software defect prediction. These three models are discussed as follows:

3.2.1. Decision Tree (DT)

Decision trees are a categorization technique for organizing data [

48,

49]. The decision tree learns how the attribute vectors act in different situations. As described by Sandeep and Sharath [

49], a decision tree is a graph in which each internal node represents a choice, and each child node represents the potential outcomes of that decision. The pathways from the tree’s root to its leaves represent the problem’s solutions. The tree-building and tree-pruning stages of the DT classification method are necessary. When generating a tree, data are partitioned recursively until each item has a single class label; when pruning, the created tree is reduced in size to avoid overfitting and boost its accuracy from the bottom up [

49,

50], see Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Decision Tree (DT) |

| 1. if D contains only training examples of the same class cj ε C then |

| 2. make T a leaf node labeled with class cj |

| 3. else if A = null then |

| 4. make T a leaf node labeled with cj, which is the most frequent class in D |

| 5 else //D contains examples of a mixture of classes. We select a single attribute |

| 6. // to partition D into subsets in order that each subgroup is purer |

| 7. po = impurityEval-1(D); |

| 8. for each attribute A1ε {A1, A2, ….., Ak} perform |

| 9. pi = impurityEval-1(D); |

| 10. end |

| 11. Select Agε {A1, A2, ….., Ak} that gives the biggest impurity reduction, |

| 12. if po – pg < threshold then //Ag does not reduce impurity po |

| 13. Make T a leaf node labeled with cj, the most frequent class in D |

| 14. else |

| 15. Make T a decision node on Ag. |

| 16. Let the possible values of V be v1, v2, ….., vm. |

| Partition D into m disjoint Subsets D1, D2, …., Dm based on m values of Ag. |

| 17. for each Djin {D1, D2, …., Dm } perform |

| 18. If Dj is not null then |

| 19. Create a branch (edge) node Tj for vj as a child node of T; |

| 20. DecisionTree (Dj, A-{Ag}, Tj) // Ag is removed |

| 21. end |

| 22. end |

| 23. end |

| 24. end |

| Decision tree Algorithm [51] |

3.2.2. K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

Similarity-based instance classification is the goal of instance base learner (IBL) or k-nearest neighbor classification [

49]. The function is merely approximated locally, and all computation is delayed until classification in this lazily-learned approach [

49]. The majority of an object’s neighbors determine its classification. Since K is always positive, the neighbors are picked from a pool of items whose labels are already known. To assign a class to a new data point, the k-nearest neighbors of that point in the training data are consulted [

52,

53]. The approach may be used to target functions with continuous or actual values [

49], see Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: K-Nearest Neighbor |

| BEGIN |

| Input: |

| Build the training dataset Di = { (X1, C1), …, (XN, CN)} |

| X = (X1, …, XN) new instance to be classified |

| For each labeled instance (Xi, Ci), perform |

| If X has an unknown system call, then |

| X is abnormal; |

| else then |

| For each process, Dj in training data perform |

| calculate Sim(X, Dj); |

| if Sim(X, Dj) == 1.0 then |

| X is normal and exit; |

| Order Sim(X, Di) from Lowest to highest, (i = 1, …, N); |

| Find K biggest scores of Sim(X, D); |

| Select the K nearest instances to X: DKX; |

| Assign to x the most frequent class in DKX; |

| Calculate Sim_Avg for k-nearest neighbors; |

| If Sim_Avg > threshold then |

| X is normal; |

| else then |

| X is abnormal; |

| END |

| kNN Algorithm [54] |

3.2.3. Naïve Bayes (NB)

The naïve Bayes algorithm is both a probabilistic classifier and a statistical classification technique; it determines a set of probabilities based on a dataset’s frequency and combinations of values. Based on the Bayes theorem, this approach treats each attribute as independent of the value of the class variable [

55,

56]. It relies on the assumption of an underlying probabilistic model and provides a logical means of capturing uncertainty employing calculated probabilities. Moreover, it helps with both diagnosis and forecasting. Naïve Bayes is based on the Thomas Bayes (1702–1761) theorem and works best when the input space has many dimensions. In addition, naïve Bayes models employ the maximum likelihood for parameter estimation. Despite its oversimplified assumptions, naïve Bayes routinely outperforms more sophisticated machine learning algorithms in complex real-world settings.

3.2.4. Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA)

To provide academics with simple access to cutting-edge machine learning methods, the Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (WEKA) was developed. In 1992, when the project began, there was a wide selection of languages, systems, and data types supported by learning algorithms. Compiling learning schemes for comparison research across many datasets was an intimidating endeavor. In addition to a collection of learning algorithms, WEKA was designed to serve as a framework in which researchers may test and deploy novel algorithms without worrying about the underlying mechanisms required to manipulate data or evaluate the efficacy of proposed solutions [

57,

58].

The algorithms were implemented in Eclipse by building a path to WEKA (Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis) API library on Eclipse. WEKA is an open-source Java software that includes a collection of several machine learning algorithms for data analysis. The algorithms can be applied directly to a dataset or called from your Java code (the technique used in this project). Moreover, WEKA contains tools for performing data preprocessing, classification, association, regression, and visualization.

3.3. Motivations for Using the Proposed Models

The reasons for using these models for SDP are as follows:

Naïve Bayes, a probabilistic classifier, works on the feature independence assumption. It works effectively on massive datasets and requires little computer resources. When working with textual data, such as source code metrics or defect descriptions, NB excels due to its ability to cope with high-dimensional feature spaces. Due to the probabilistic nature of the algorithm, it can make accurate predictions quickly.

Decision trees are flexible models that may be easily understood and used for numerical and categorical information. They have the potential to capture intricate interrelationships between characteristics. DT is helpful for software defect prediction since they lighten the crucial aspects and how they affect the forecast. The resultant tree structure is simple to understand and relay to relevant parties, facilitating decision-making and troubleshooting.

Instances are sorted into groups using the k-nearest neighbor non-parametric approach based on their spatial closeness to other groups in the feature space. There is no implicit data distribution assumption. When software faults cluster in the same geographical area, kNN is an appropriate method for defect prediction. It can create accurate predictions based on closest neighbors by accurately capturing the similarity between occurrences. KNN is particularly flexible in that it can process data with both numerical and categorical characteristics.

A combination logic used the best features of all three models. The three models’ predictions were integrated using dagging learning, which improved the total performance.

3.4. Proposed Architecture

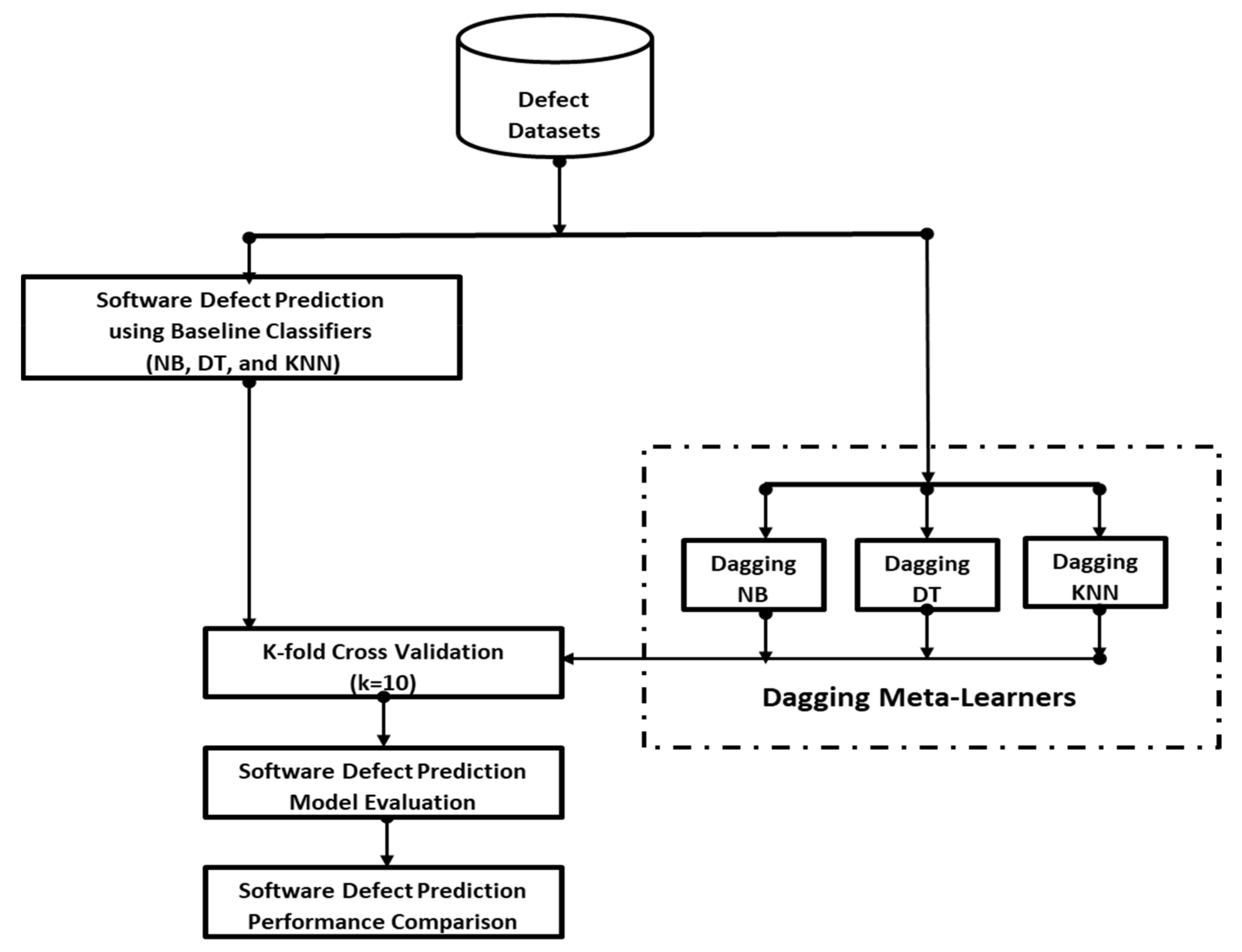

The study’s proposed architecture is shown in

Figure 1. The methodology established is designed to experimentally evaluate and validate the efficacy of the offered approaches. The experimental framework is applied to nine NASA software defect datasets, and SDP models are created using K-fold (k = 10) cross-validation (CV). Due to its ability to construct phishing models with low bias and variance, the K-fold CV is preferred [

59]. Furthermore, with the CV approach, each instance from a dataset is repeatedly utilized for training and testing. The CV approach is explained in detail in [

60,

61]. With faulty datasets based on a 10-fold CV, the suggested approaches and basic classifiers (NB, DT, and kNN) are trained and evaluated. The created SDP models’ prediction performance is assessed and examined. The suggested approaches are implemented using WEKA machine learning tools and libraries [

57].

4. Results and Discussion

This study seeks to investigate the effect of wrapper feature selection methods on heterogeneous classifiers in SDP. This experiment was carried out by implementing the WEKA library using Eclipse IDE. This chapter presents the results generated after carrying out the research work. The tools (Eclipse and WEKA Library) used in carrying out this project work are open-source tools, and they can run on both Windows and Linux Operating Systems, a system with a minimum of 50 Gigabyte Hard Disk, and finally, a system with a minimum of 2 Gigabyte RAM (memory).

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 demonstrate the average prediction performance outcomes of experimented SDP models used over nine datasets, each divided into train and test datasets. Each table illustrates the results of the dagging-based classifiers and baseline classifiers.

Table 3 displays the accuracy values of a particular heterogeneous classifier and proposed dagging-based classifiers over nine SDP datasets.

Table 3 shows some observations: Concerning accuracy, the dagging-based classifiers are better than baseline classifiers. In particular, Dagging_NB had an average accuracy value of 0.838%, which is superior to baseline NB (0.749%) by +11.1%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average accuracy value of 83.44%, which is +3.9% better than the baseline DT (0.803%). Dagging_KNN (0.832%) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (0.792%) by +5.1%. Based on the preceding experimental results, it can be deduced that dagging meta-learner-based classification can improve the prediction accuracy values of SDP models.

Figure 2 presents a graphical representation of the average accuracy values of experimented SDP models in this study.

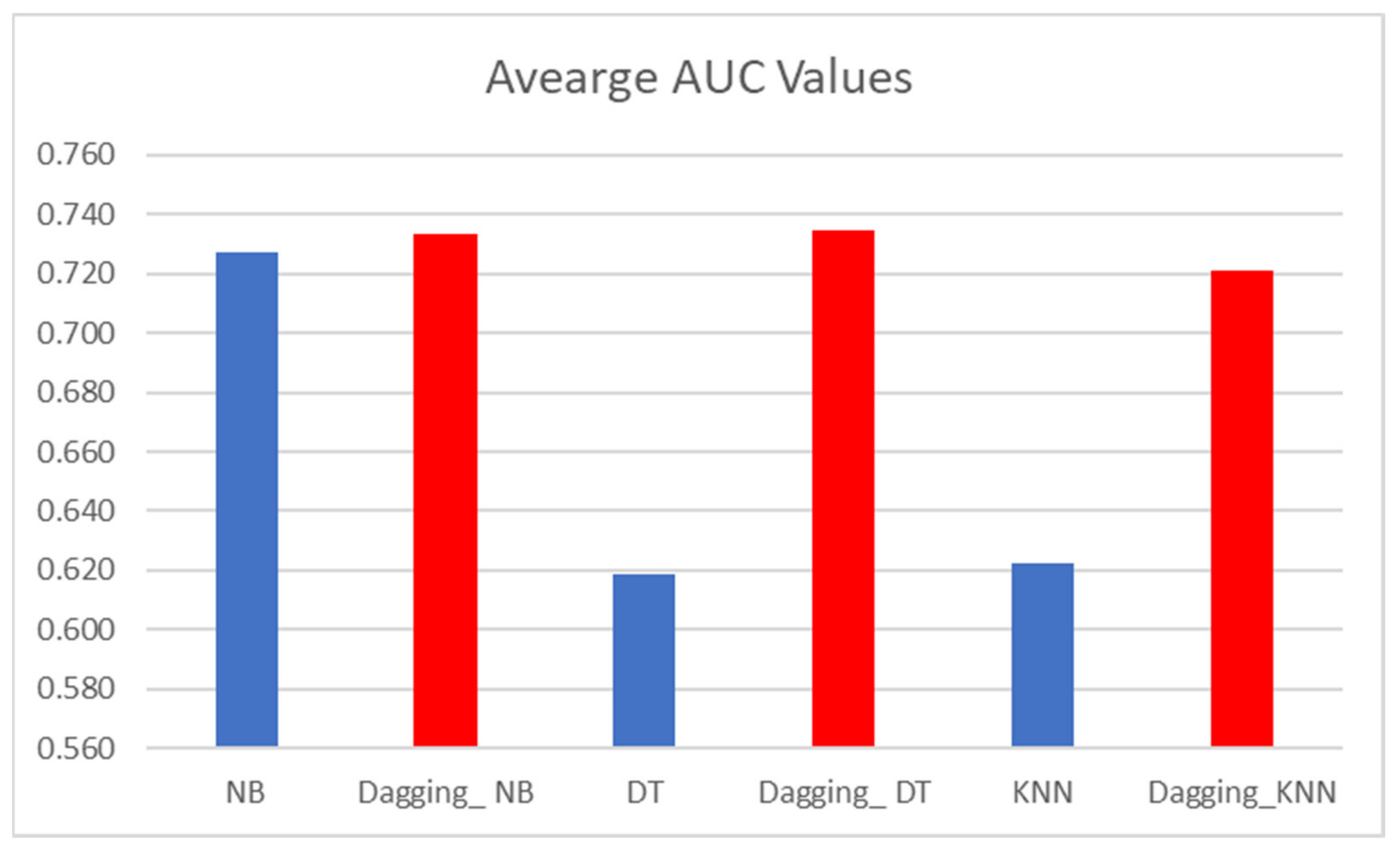

Concerning AUC values,

Table 4 presents the AUC values of dagging-based classifiers and baseline classifiers. Similar to the accuracy values, dagging-based SDP models have superior AUC values than models based on baseline (NB, DT, kNN) classifiers. Specifically, Dagging_NB had an average AUC value of 0.785, which is superior to baseline NB (0.727) by +7.98%. Furthermore, Dagging_DT recorded an average AUC value of 0.78, which is +26% better than the baseline DT (0.619). Dagging_KNN (0.777) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (0.622) by +24.9%. Correspondingly, it can be observed that dagging-based classification further improved the AUC values of SDP models. In addition, SDP models based on dagging had AUC values close to 1, namely, SDP models based on dagging have a high ability to predict defects and are not subject to change. This observation further strengthens the findings from

Table 3, namely, SDP models based on dagging are a good fit.

Figure 3 presents a graphical representation of the average AUC values of dagging-based classifiers and baseline SDP models.

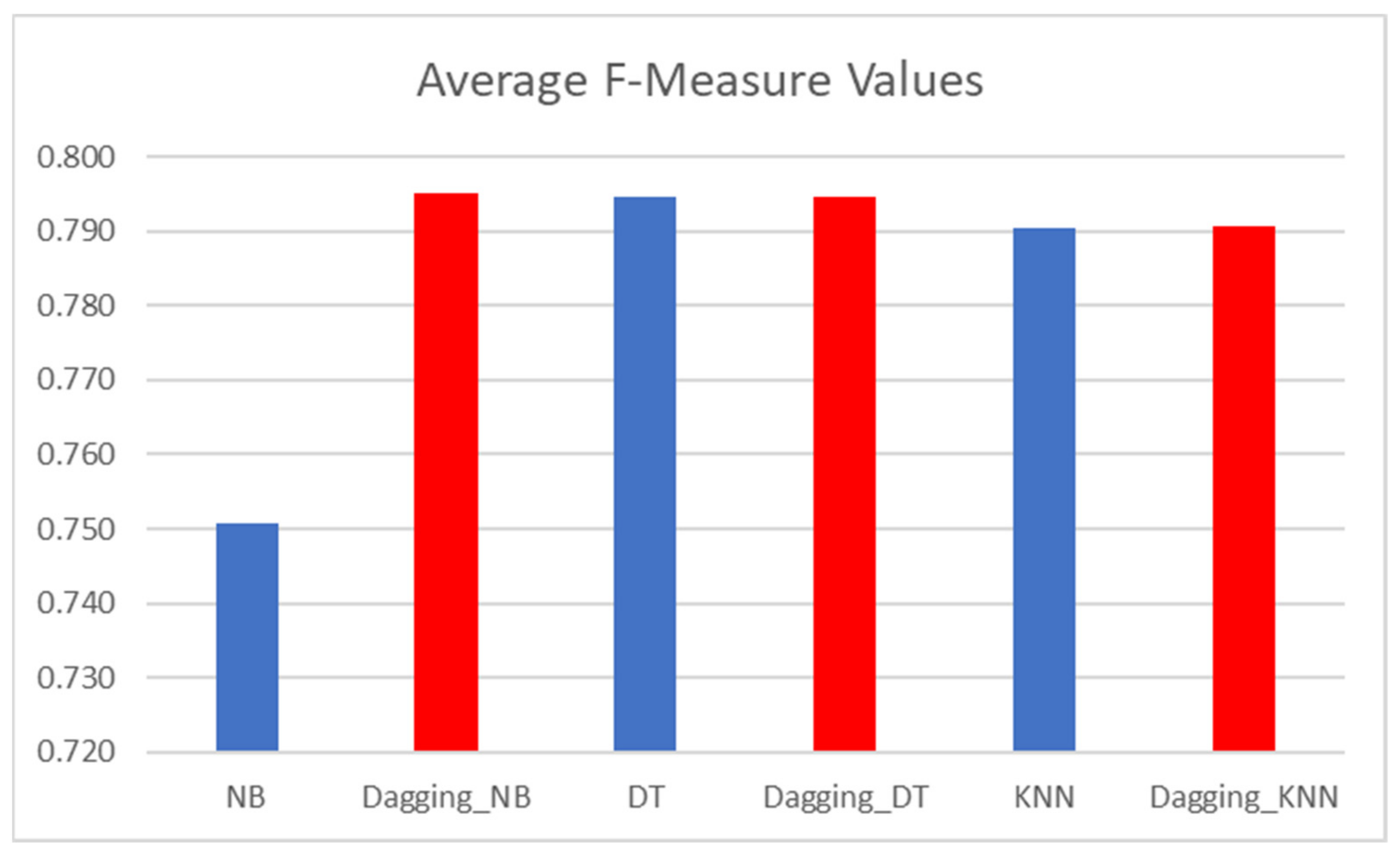

In terms of F-measure values,

Table 5 shows the F-measure values of dagging-based classifiers and baseline classifiers. Moreover, similar to the initial results in

Table 3 and

Table 4, dagging-based SDP models have better F-measure values than models based on baseline (NB, DT, kNN) classifiers. Specifically, Dagging_NB had an average F-measure value of 0.805, which is superior to baseline NB (0.751) by +7.19%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average AUC value of 0.808, which is +1.64% better than baseline DT (0.795). Dagging_KNN (0.790) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (0.807) by +2.15%. Correspondingly, it can be observed that dagging meta-learner classifier further enhanced the F-measure values of SDP models. This observation further strengthens and agrees with the findings from

Table 3 and

Table 4. Similarly,

Figure 4 presents a graphical representation of the average AUC values of dagging meta-learner and baseline SDP models.

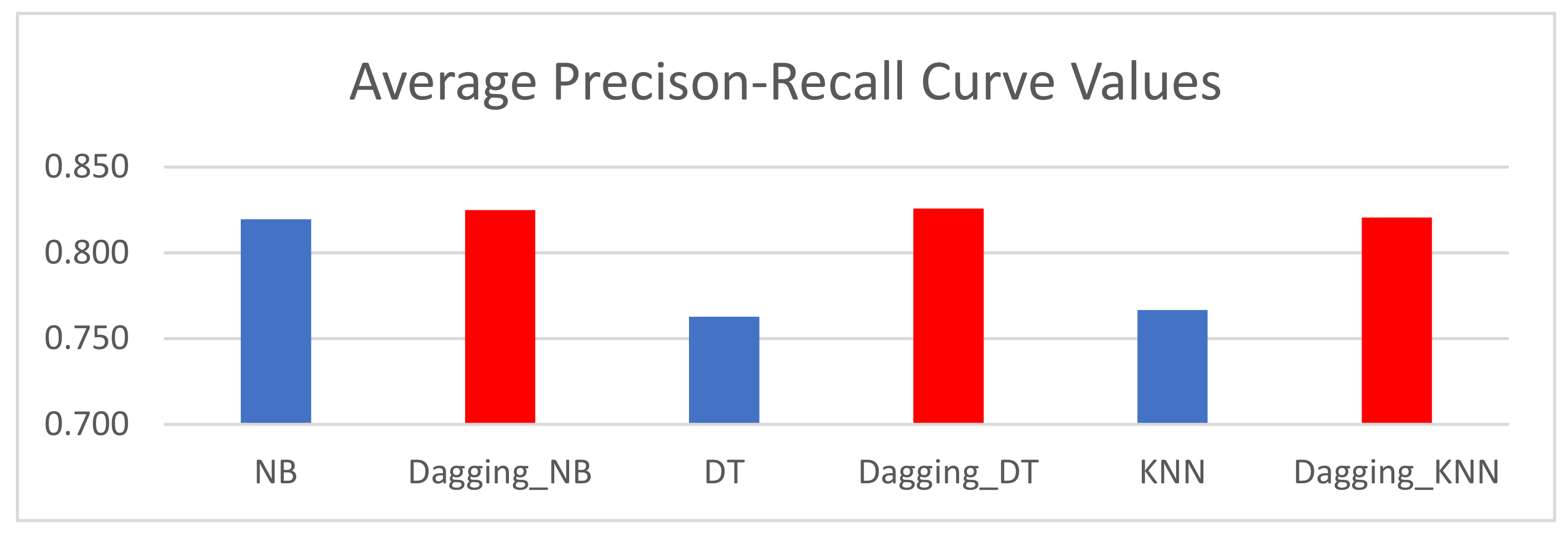

Finally,

Table 6 presents the precision-recall curve (PRC) values of the baseline and projected dagging-based classifiers. The PRC value is built on the precision and recall values of the developed SDP models. It recaps the trade-off between the TPR and the positive prognostic rate for various probability thresholds in a predictive model. It can also be deduced from

Table 6 that SDP models founded on dagging meta-learner classifiers are better than baseline classifiers, in particular. Dagging_NB had an average accuracy value of 0.853, which is superior to baseline NB (0.820) by +4.02%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average accuracy value of 0.847, which was +11.1% better than baseline DT (0.763). Dagging_KNN (0.847) had a greater average F-measure rate over baseline kNN (0.767) by +10.43%. Based on these investigational outcomes, it can be discovered that SDP models founded on dagging meta-learner classifiers are superior to SDP models based on baseline classifiers. A graphical representation of the PRC values is presented in

Figure 5.

Compared to baseline classifiers, the high and better prediction performance of dagging meta-learner-based SDP models on the analyzed datasets indicates their corresponding small risk of misprediction of software flaws. Furthermore, the suggested approaches are extra resilient and robust to prejudices in the examined datasets (class imbalance and high dimensionality) than the baseline classifiers, as seen by the high AUC values of dagging meta-learner-based SDP models (NB, DT, and kNN). In particular, the suggested approaches outperform baseline classifiers in predicting software defects due to class imbalance and high-dimensionality issues that might be present in software defect datasets.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Software businesses must concentrate their limited SQA resources on software segments (such as source code files) that are probably problematic. Statistical or machine learning classification approaches are used to train defect forecasting methods to recognize fault-prone software segments. ML algorithms have varying levels of efficiency, which might vary depending on the performance measurements used and the conditions.

This study aimed to observe how successful dagging meta-learner-based SDP models predict software defect problems. Dagging-based classifiers and baseline classifiers, such as NB, DT, and kNN were used on nine NASA datasets. The experimental findings revealed that SDP models were built on dagging meta-learner beat-tested baseline classifiers regarding accuracy, AUC, F-measure, and PRC values. Dagging_NB had an average accuracy value of 83.75%, which is superior to baseline NB (74.93%) by +11.06%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average accuracy value of 83.44%, which is +3.91% better than the baseline DT (80.30%). Dagging_KNN (83.24%) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (79.17%) by +5.14%.

Similarly, Dagging_NB had an average AUC value of 0.785, which is superior to baseline NB (0.727) by +7.98%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average AUC value of 0.78, which is +26% better than baseline DT (0.619). Dagging_KNN (0.777) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (0.622) by +24.9%. Correspondingly, Dagging_NB had an average F-measure value of 0.805, which is superior to baseline NB (0.751) by +7.19%. Furthermore, Dagging_DT recorded an average AUC value of 0.808, which is +1.64% better than baseline DT (0.795). Dagging_KNN (0.790) had a superior average accuracy value over baseline kNN (0.807) by +2.15%.

Finally, it was observed that Dagging_NB had an average accuracy value of 0.853, which is superior to baseline NB (0.820) by +4.02%. Moreover, Dagging_DT recorded an average accuracy value of 0.847, which was +11.1% better than baseline DT (0.763). Dagging_KNN (0.847) had a greater average F-measure rate over baseline kNN (0.767) by +10.43%. Therefore, it can be concluded that since dagging meta-learner outperformed baseline classifiers in terms of accuracy, AUC, F-measure, and PRC values, it may be used to improve SDP model prediction performance and should be considered for SDP procedures.

In the future, more effective SDP approaches or processes can be developed by implementing deep learning algorithms, optimization algorithms, or even dimensionality-reduction algorithms. Several datasets can be gathered and validated by employing numerous other ML techniques for defect forecasting. More research is planned to integrate the abovementioned models with different machine learning approaches to produce prediction models that can forecast software dependability more correctly and with fewer accuracy errors.

Furthermore, we proposed the examination of recent emerging domains, such as tabu search with simulated annealing for solving a location–protection–disruption in hub network, dark-side avoidance of mobile applications with data biases elimination in the socio-cyber world, etc., in which recent methods, such as tabu search and anomaly detection will be researched in future research. Some other ML models, such as XGBoost, AdaBoost, and LightGBM, are proposed to be implemented in the future.