Abstract

Metaheuristic algorithms are an important area of research in artificial intelligence. The tumbleweed optimization algorithm (TOA) is the newest metaheuristic optimization algorithm that mimics the growth and reproduction of tumbleweeds. In practice, chaotic maps have proven to be an improved method of optimization algorithms, allowing the algorithm to jump out of the local optimum, maintain population diversity, and improve global search ability. This paper presents a chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm (CTOA) that incorporates chaotic maps into the optimization process of the TOA. By using 12 common chaotic maps, the proposed CTOA aims to improve population diversity and global exploration and to prevent the algorithm from falling into local optima. The performance of CTOA is tested using 28 benchmark functions from CEC2013, and the results show that the circle map is the most effective in improving the accuracy and convergence speed of CTOA, especially in 50D.

Keywords:

tumbleweed optimization algorithm; chaotic map; random initialization; metaheuristic optimization MSC:

90C26

1. Introduction

As science and technology continue to advance and production capacity improves, the complexity of optimization problems is increasing. Finding efficient solution algorithms for these complex problems has become an urgent issue to be addressed. The emergence of metaheuristic algorithms provides a promising approach to solving optimization problems [1]. They are inspired by natural evolutionary laws, which have been shaped over tens of thousands of years to improve survival and to ensure that populations evolve.

Researchers have investigated these natural phenomena and designed algorithms to solve complex problems. The optimization problem is abstracted into the optimal solution of population evolution in this algorithm, the space of numerical search is abstracted into the living environment, and the behavior of each individual in the population represents a set of solutions. By continuously evolving the biological characteristics of its own population from an initial state, an optimal solution can be obtained, such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) [2], genetic algorithm (GA) [3], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [4], grey wolf optimizer (GWO) [5], salp swarm algorithm (SSA) [6], ant colony optimization (ACO) [7], or shuffled frog leaping algorithm (SFLA) [8]. These efficient and robust algorithms have been successfully applied to solve various problems such as complex engineering problems [9,10,11], neural network [12,13,14,15], shortest path optimization [16,17], feature selection [18,19,20], and power scheduling [21].

Although metaheuristic algorithms can solve optimization problems in large-scale search spaces, Sheikholeslami et al. [22] showed that a sufficiently random sequence is required to ensure better performance in the algorithm’s global search phase, especially for metaheuristic algorithms that simulate and make decisions for complex natural phenomena. Population initialization is a critical component of metaheuristic algorithms. It has a direct impact on the algorithm’s search efficiency and the quality of the final solution. As a result, researchers have been investigating various methods to improve population initialization in order to solve practical problems more effectively. Randomized initialization is one of the most common metaheuristic initialization methods, in which a population is built by randomly generating solutions in the search space. This method is used by the majority of algorithms, such as those in [23,24]. THe initialization of opposition-based learning (OBL) randomly generates a set of solutions as the initial population and then generates an opposite solution, such as in [25,26]. Cluster-based initialization is a method that uses a clustering algorithm to divide the solutions. These solutions with similar patterns are assigned into several categories [27], such as in [28,29]. The use of chaotic maps is one of the most effective ways to generate a sufficiently random and well-distributed initialization sequence for metaheuristic algorithms, such as in [30,31,32,33]. By combining chaotic maps and metaheuristic algorithms, various optimization problems have been improved. For example, Gandomi et al. [34] proposed a chaos-accelerated particle swarm algorithm in 2013, and Arora et al. [35] proposed using chaos to improve the butterfly algorithm in 2017. The above-mentioned studies have obtained good experimental results. Kohli et al. [36] proposed a chaotic gray wolf optimization algorithm for constrained problems, and experiments proved that this method is very effective. Jia et al. [37] applied chaos theory to differential evolution and proved the feasibility of a chaotic local search strategy.

The tumbleweed optimization algorithm (TOA) [38] is a newly proposed metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the growth and reproduction behavior of tumbleweeds. Here are several existing research gaps and our motivations in this study:

- Currently, no studies focus on chaotic-based TOA algorithms. Previous studies have shown that by combining chaotic maps with metaheuristic algorithms, various optimization problems have been improved. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, we propose a chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm (named CTOA).

- In order to obtain the best performance of CTOA, we verify 12 chaotic maps. In our experiments, CEC2013, Friedman ranking test, and Wilcoxon test are adopted. Meanwhile, a real problem–power generation prediction is involved for evaluation.

Therefore, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- In this study, we combine chaotic maps with the TOA algorithm for the first time to propose a chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm (CTOA).

- We select 12 different chaotic maps and 28 popular benchmark functions to evaluate the performance of the proposed CTOA algorithm. The experimental results demonstrate that the performance and convergence of CTOA are greatly enhanced. We conclude that the best CTOA algorithm is CTOA9 (circle map + TOA).

- Finally, we compare CTOA9 with famous state-of-art optimization algorithms, including GA [3], PSO [2], ACO [7], and SFLA [8]. The results demonstrate that CTOA9 is not only the best in the Friedman ranking test and Wilcoxon test, but it also has the minimum error when applied to power generation prediction problems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, a literature review is provided to summarize the existing research on chaotic-based metaheuristic optimization algorithms. We present the CTOA, which integrates twelve selected chaotic maps into TOA in Section 3. The experimental evaluation of the CTOA on a range of benchmark functions is presented in Section 4. Section 5 provides a detailed application of real problem–power generation prediction. The discussion is described in Section 6 and the conclusion is described in Section 7.

2. Related Work

One area of interest in recent years has been the use of chaotic map strategies to enhance metaheuristic algorithms. Several studies have explored the use of chaotic maps to improve the performance of metaheuristic algorithms. In 2018, Sayed et al. [39] proposed a new chaotic multi-variate optimization algorithm (CMVO) to overcome the problems of low convergence speed and local optimum in MVO. To help control the rate of exploration and exploitation, ten well-known chaotic maps were selected for their research. Experimental results show that the sinusoidal map can significantly improve the performance of the original MVO. Similarly, Du et al. [40], in 2018, proposed the use of linear decreasing and a logical chaotic map to enhance the fruit fly algorithm, named DSLC-FOA, which produced better results than the original FOA and other metaheuristic algorithms.

Tharwat et al. [41], in 2019, developed a chaotic particle swarm optimization (CPSO) to optimize path planning and demonstrated its high accuracy by adjusting multiple variables in a Bezier curve-based path planning model. Kaveh et al. [42] proposed a Gauss map-based chaotic firefly algorithm (CGFA). Experimental results show that chaotic maps can improve convergence and prevent the algorithm from getting stuck in locally optimal solutions. In 2020, Demidova et al. [43] applied two strategies of different chaotic maps with symmetric distribution and exponential step decay to the fish school search optimization algorithm (FSS) to solve the shortcomings of poor convergence speed of FSS and low precision in high-dimensional optimization problems. Ultimately, the results of the study showed that FSS using tent map produced the most accurate results. Similar to this study, Li et al. [44] also proved that the chaotic whale optimization algorithm generated by the tent map when improving the WOA has higher accuracy in numerical simulation.

In 2021, Agrawal et al. [45] used chaotic maps to improve the gaining sharing knowledge-based optimization algorithm (GSK) and applied this new algorithm to feature selection. The results indicate that the Chebyshev map shows the best result among all chaotic maps, improving the original algorithm’s performance accuracy and convergence speed. In 2022, Li et al. [46] proposed the chaotic arithmetic optimization algorithm (CAOA). The CAOA based on chaotic disturbance factors has the advantage of balancing exploration and exploitation in the optimization process. Onay et al. [47] applied ten chaotic maps to the classic hunger games search (HGS), and they were also evaluated on the classic benchmark problems in CEC2017.

Recently, Yang et al. [48] used the tent map to improve the population diversity of WOA [4]. They also optimized the parameters and network size of the radial basis function neural network (RBFNN). Luo et al. [49] proposed an improved bald eagle algorithm that combined with the tent map and Levy fight method. This improved algorithm can expand the diversity of the population and search space. Naik et al. [50] introduced chaos theory into the modification of the social group optimization (SGO) algorithm, by replacing constant values with chaotic maps. The chaotic social group optimization algorithm proposed by them improves its convergence speed and results in precision.

In summary, the use of chaotic map strategies has shown promise in improving the performance of various metaheuristic algorithms. The selection of a suitable chaotic map for a given optimization algorithm can lead to a significant improvement in its convergence speed and precision. The summaries of these studies are shown in Table 1. The potential of chaotic map strategies in improving optimization algorithms remains an active area of research, and further studies are necessary to explore their effectiveness in different optimization problems.

Table 1.

Literature summary of optimization algorithms improved by a chaotic map.

3. Proposed Chaotic-Based Tumbleweed Optimization Algorithm

In this section, we briefly review the TOA, and a chaotic-based TOA called CTOA is proposed. To make the algorithm easier to understand, some important notations are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relevant notations.

3.1. Tumbleweed Optimization Algorithm (TOA)

TOA not only sets up search individuals such as traditional algorithms but also uses a grouping structure. That is, a tumbleweed population has subpopulations, each of which has multiple search individuals [38]. A multi-level grouping structure such as this can improve the TOA algorithm’s ability to find optimal values, and multi-subgroups can also prevent the appearance of local optima.

These two steps in the algorithm correspond to the tumbleweed population’s individual growth and reproduction procedures. The two stages of individual growth and individual reproduction are both equally important for population evolution and hence account for half of the tumbleweed growth cycle.

3.1.1. Individual Growth-Local Search

In a local searching process, the influence of the environment on the ith individual during kth cycle () is represented by in Equation (1):

where is a random number between 0 and 1, and is a matrix whose elements are all individuals of this iteration. The greater the value of , the greater the adaptability of tumbleweed seeds in this environment. The fitness will be sorted in the TOA and will generate . The top 50% will be saved to compete against other subpopulations using Equations (2) and (3).

Then, the mathematical expression for each individual in the subpopulation is shown as follows:

where , , are random numbers, and they are all in the range from 0 to 2. The remaining 50% cannot compete with other subpopulations using (4). The subpopulation with poor environmental adaptability cannot compete, but it can take out intra-population evolution, and the evolution formula is expressed in Equation (4):

where , is a random number from 0 to 1, and represents the influence of the external environment on the individual, which will gradually decrease linearly with iteration.

3.1.2. Individual Reproduction—Global Search

The global search phase corresponds to tumbleweed reproduction after adulthood. Tumbleweeds spread their own seeds for reproduction while doing so. Equation (5) depicts the evolutionary formula for this process:

where V is a random velocity vector of the seed falling.

3.2. Chaotic-Based Tumbleweed Optimization Algorithm (CTOA)

In the TOA, the population is randomly initialized with a Gaussian probability distribution in Equation (6):

where is a random matrix with elements in the range from 0 to 1. Then, these two processes in TOA correspond to the tumbleweed population’s local searching and global searching. After random initialization of TOA, the produced sequences may not be well distributed, and this may affect the search results according to different sequences. This phenomenon will reduce the robustness of the optimization algorithm.

Here, we proposed an approach to replace the randomly generated population. First, an initial vector needs to be given, and Equation (7) is used to generate an X matrix containing a chaotic sequence:

where represents the selected chaotic map. The solution of the next generation in the chaotic sequence is to input the solution of the previous generation into the chaotic mapping function.

Next, then with chaotic properties is generated using Equation (8):

where is the minimum value of the search solution space, and is the maximum value of the search solution space. The dimension of X must be the same as the dimension of .

After finishing Equations (7) and (8), the chaotic population initialization of is completed. When an algorithm requires a random sequence to initialize the population position, the chaotic sequence replaces the original random sequence using Equations (7) and (8) and chaotic maps. Therefore, the chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm (CTOA) is proposed. The distribution of the initial population is affected by the chaotic sequence, and the position in the target space is more random. Therefore, the basic steps of the CTOA are as follows:

Step 1: Generate the initial input data randomly.

Step 2: Iterate the selected chaotic map and produce a chaotic sequence X.

Step 3: Generate a chaotic population , where the boundary of needs to be controlled by Equations (7) and (8).

Step 4: Complete the individual search part of CTOA using the chaotic population from Step 3.

Step 5: Complete the global exploration part of CTOA.

Step 6: Obtain a feasible solution.

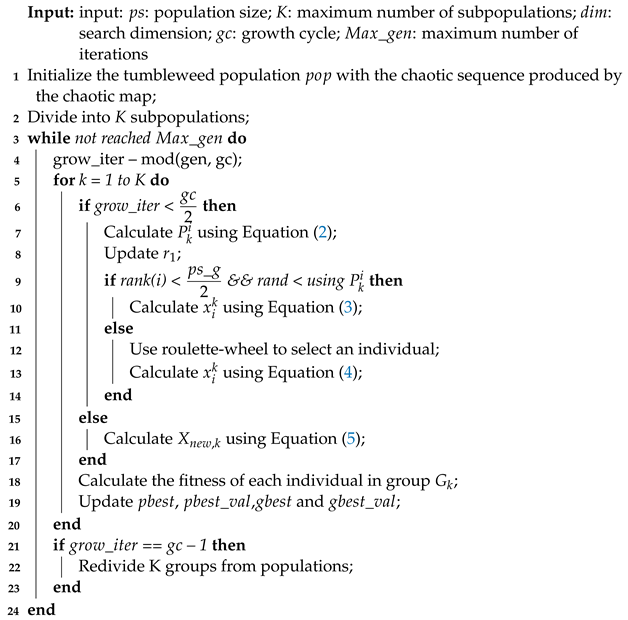

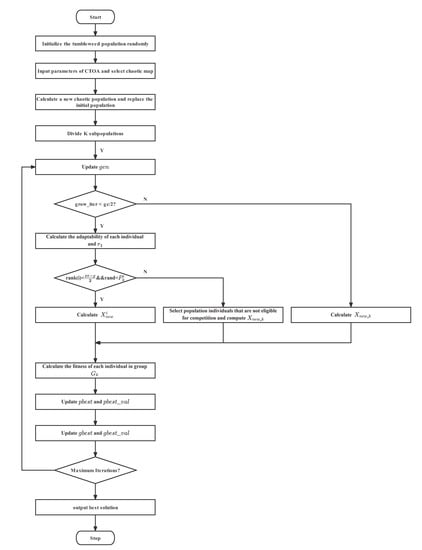

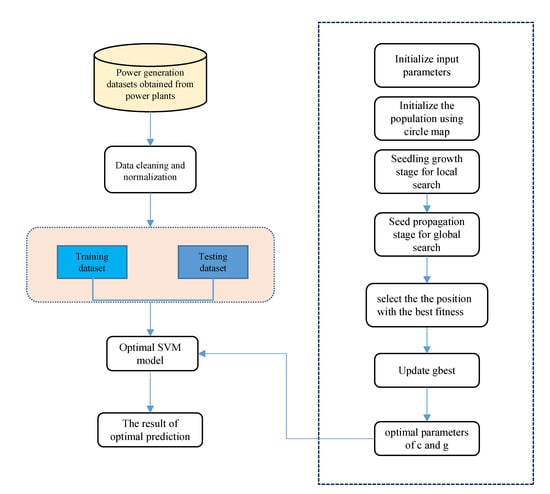

Algorithm 1 shows the pseudocode for the CTOA’s entire optimization process. The complete process of CTOA is also given in Figure 1 in the form of a flowchart.

| Algorithm 1: Pseudo-code of the CTOA |

|

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the CTOA procedure.

4. Experimental Result

In this section, we conduct experiments to determine which chaotic map is best suited for use in our proposed CTOA algorithm.

4.1. Experimental Environment and Benchmark Function

All the results presented in this section were obtained through MATLAB R2022b and Python3 simulations on a machine equipped with 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-11900 and 64 G RAM. Before conducting the experimental tests, we initialized the running parameters as shown in Table 3. The initial population size was set to 100 to ensure that the position distribution of individuals initialized using chaotic maps was more characteristic. The number of function runs was set to 50 to prevent random results from causing errors in the final evaluation results. To facilitate comparisons between the CTOA algorithm and the unimproved TOA algorithm, the 12 different CTOA algorithms are labeled as CPP1 to CPPE12, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Names of parameters and their default values.

Table 4.

The meanings of algorithm symbols.

The IEEE Evolutionary Computing Conference announced the appearance of the benchmark function [60] in order to conduct a comprehensive performance comparison of metaheuristic algorithms and to verify the performance of the proposed algorithm. To evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm, we used the benchmark functions from the CEC2013 suite, which includes 28 benchmark functions separated into three categories: unimodal function, multimodal function, and composition function. Functions F1–F5 are unimodal functions, F6–F20 are multimodal functions, and F21–F28 are composite functions. The names and details of the benchmark functions are shown in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Unimodal benchmark functions have a single minimum value in the search interval, which is used to test the convergence speed of CTOA. Multimodal benchmark functions have higher requirements for CTOA than unimodal functions since they have multiple local minima that can test CTOA’s ability to jump out of local optima. The composition benchmark function is a combination of the two aforementioned functions. These benchmark functions enable us to evaluate CTOA’s performance across multiple dimensions.

Table 5.

Descriptive information about the unimodal benchmark function.

Table 6.

Descriptive information about the multimodal benchmark function.

Table 7.

Descriptive information about the composition benchmark function.

4.2. Experimental Result on Numerical Statistics

In the experiments, we used three criterions of algorithm performance as follows:

where represents the algorithm’s best result in the test, is the average of 50 tests, and stands for standard deviation. The historical results of the algorithm obtained after 50 runs of CEC2013 are represented by . Each algorithm’s , , and conditions are used to determine whether an experiment is good or bad. The reflects the algorithm’s limit, the reflects the algorithm’s accuracy, and the reflects the algorithm’s stability. To demonstrate the performance and robustness of CTOA in different dimensions, we run CTOA, presented in Table 4, at 30D, 50D, and 100D, and record the experimental data in these dimensions.

In addition, in order to visually demonstrate the improvement of the TOA by the initialization of the chaotic map, the experimental results of TOA in these three dimensions are also counted in the table. Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 record the results of the algorithms in Table 4 running in 30D, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15 record the results of running in 50D, and Table 16, Table 17, Table 18 and Table 19 record the results of running in 100D. Note that the experiments’ best results have been highlighted in bold.

Table 8.

Experimental results running on F1–F8 in 30D.

Table 9.

Experimental results running on F9–F16 in 30D.

Table 10.

Experimental results running on F17–F24 in 30D.

Table 11.

Experimental results running on F25–F28 in 30D.

Table 12.

Experimental results running on F1–F8 in 50D.

Table 13.

Experimental results running on F9–F16 in 50D.

Table 14.

Experimental results running on F17–F24 in 50D.

Table 15.

Experimental results running on F25–F28 in 50D.

Table 16.

Experimental results running on F1–F8 in 100D.

Table 17.

Experimental results running on F9–F16 in 100D.

Table 18.

Experimental results running on F17–F24 in 100D.

Table 19.

Experimental results running on F25–F28 in 100D.

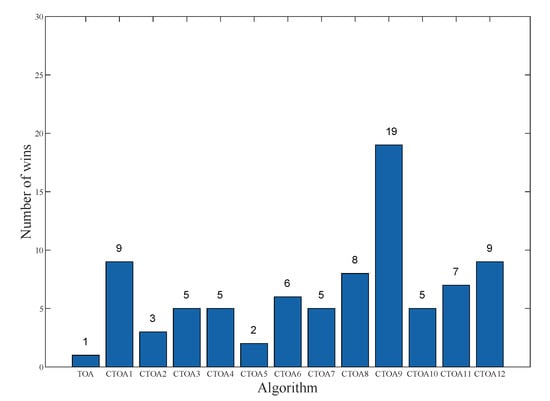

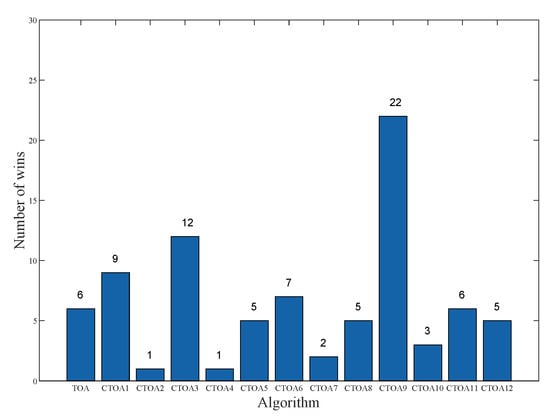

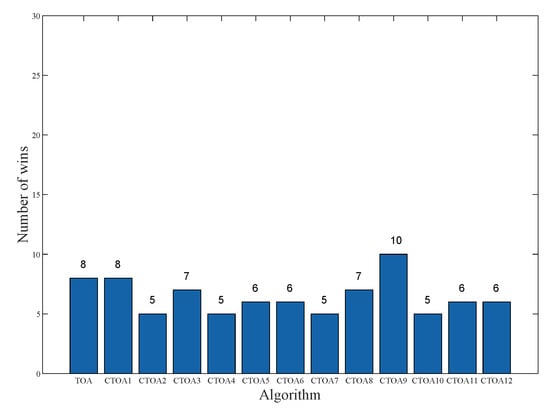

To evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm, we defined the best results as “win” in the experiments, and the better the performance of the algorithm, the more “wins” it will obtain. The experimental results of the final algorithm running in different dimensions, as well as the number of “win” obtained, are presented in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. The results indicate that CTOA initialized with chaotic mappings outperforms TOA in most cases. Specifically, in 30D, the number of wins of TOA is only one, while the number of wins of CTOA is greater than that of TOA. Furthermore, the effect of CTOA9 is found to be the best in 30D, 50D, and 100D, far exceeding other CTOAs and TOAs. Notably, in 30D and 50D, the number of wins of CTOA is about 20 times higher than that of TOA. In 50D, CTOA9 has 22 wins, which is also the highest among these algorithms. These results suggest that the circle map has the most significant improvement in the algorithm performance of TOA.

Figure 2.

The number of wins for different algorithms in 30D.

Figure 3.

The number of wins for different algorithms in 50D.

Figure 4.

The number of wins for different algorithms in 100D.

The Friedman rank test is a nonparametric statistical test method. It is used to understand and compare overall rankings of algorithms. The Wilcoxon test is used to statistically compare the performance of two algorithms chosen to solve a particular problem. Table 20, Table 21 and Table 22 show the results of the Friedman ranking test for different algorithms in different dimensions. In the Friedman ranking, each algorithm obtains a Friedman Ranking, and the smaller the Friedman Ranking, the better the performance of the algorithm. From the tables, CTOA9 ranks first in both 30D and 50D, which means that the algorithm can achieve the best performance in these dimensions. Although CTOA9 did not obtain first place in Friedman’s ranking in 100D, the ranking is also very high, only a 6% difference from the optimal algorithm. The results of the Wilcoxon test are shown in Table 23. We selected a significance level of 0.05 and converted the weighted average of the evaluation indicators in the three dimensions into rank data. A p value < 0.05 indicates that the difference between the two algorithms is significant and the result is marked as 1. Except for CTOA3 and CTOA7, CTOA9 shows a significant difference compared to all other algorithms.

Table 20.

Friedman ranking of different algorithms in 30D.

Table 21.

Friedman ranking of different algorithms in 50D.

Table 22.

Friedman ranking of different algorithms in 100D.

Table 23.

The results of the Wilcoxon test.

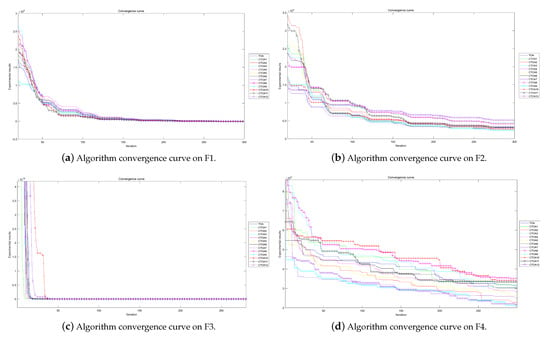

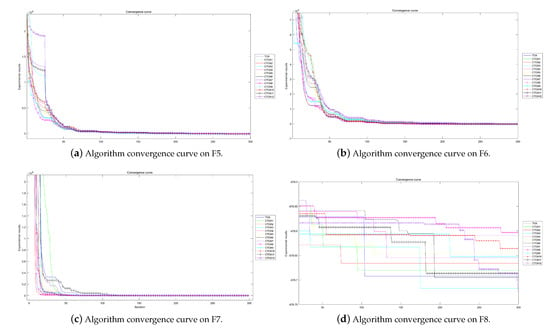

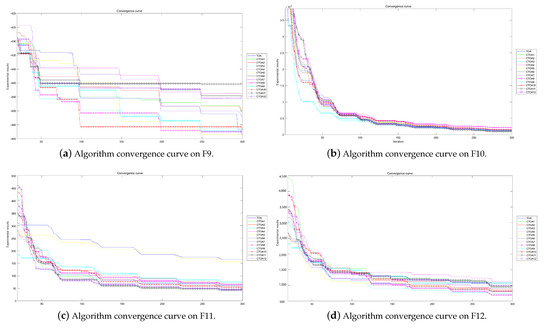

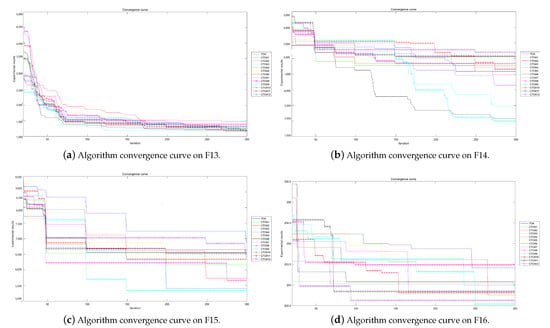

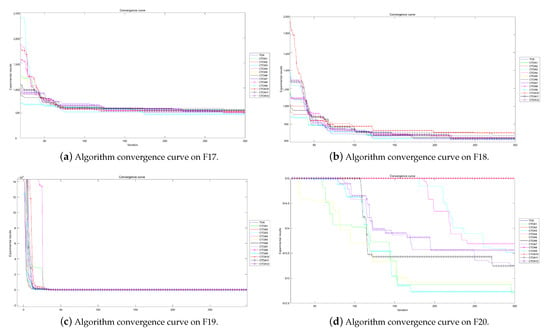

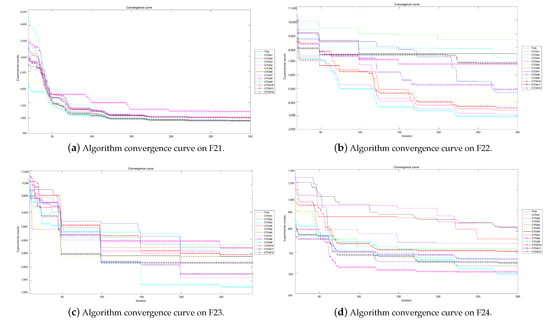

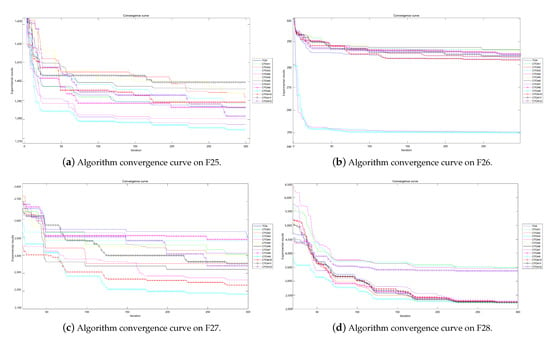

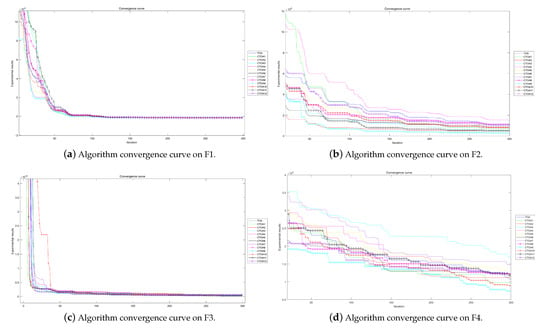

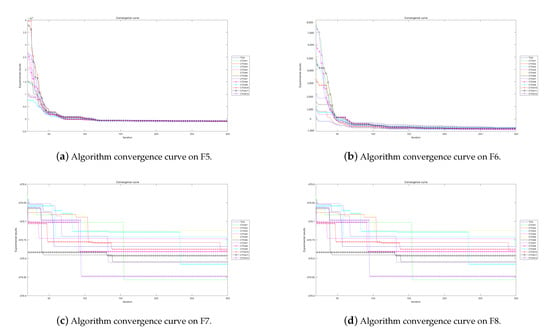

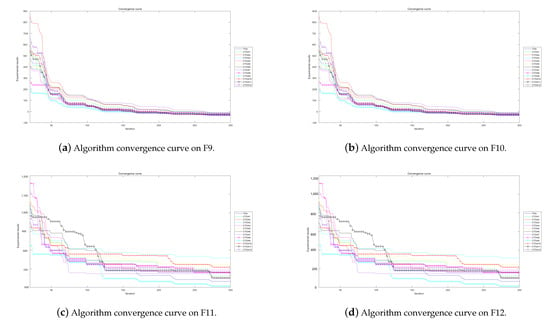

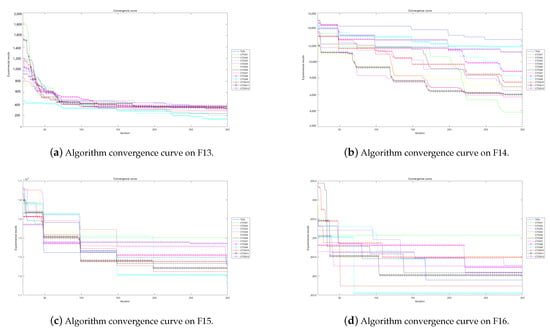

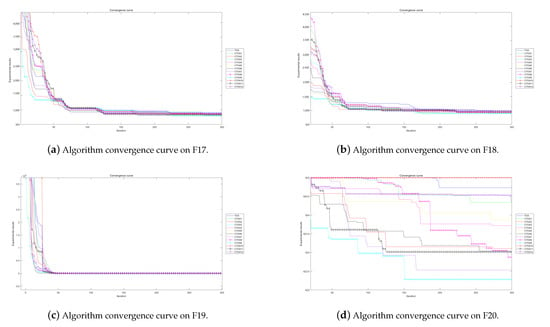

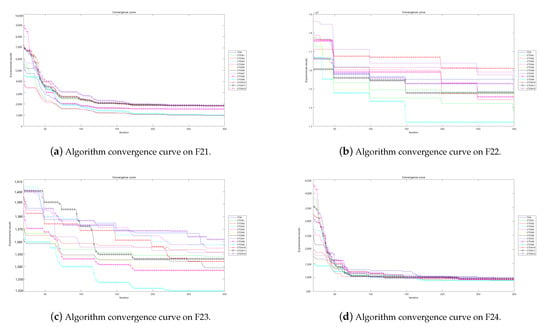

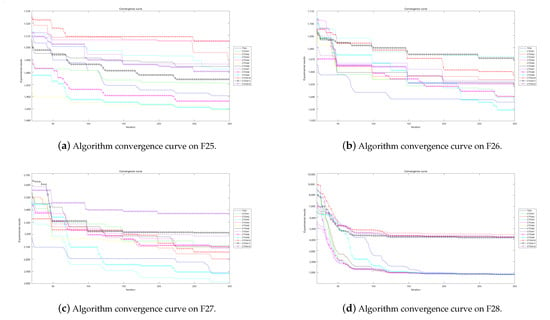

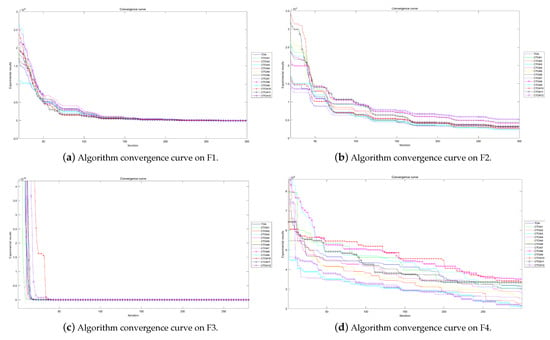

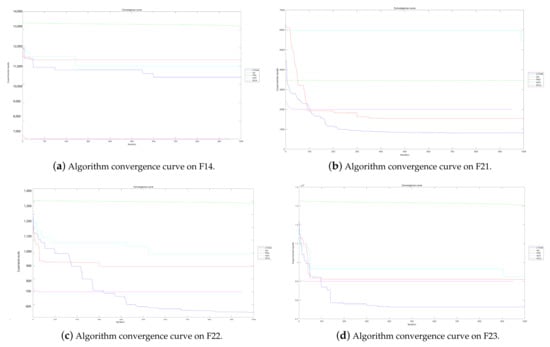

4.3. Experimental Results on Convergence

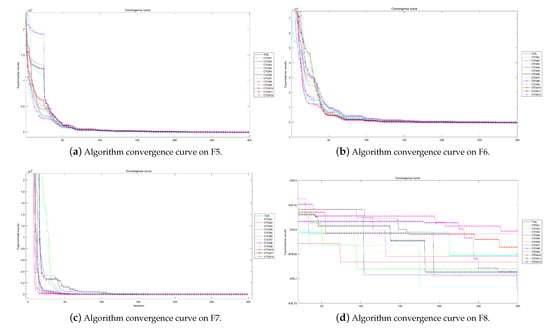

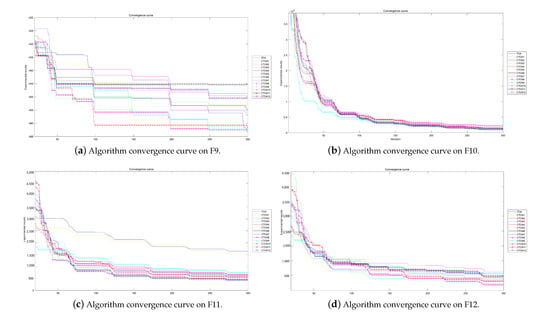

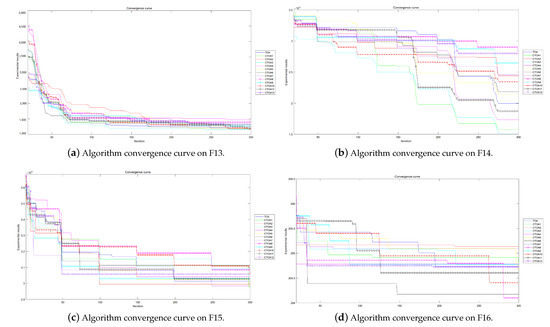

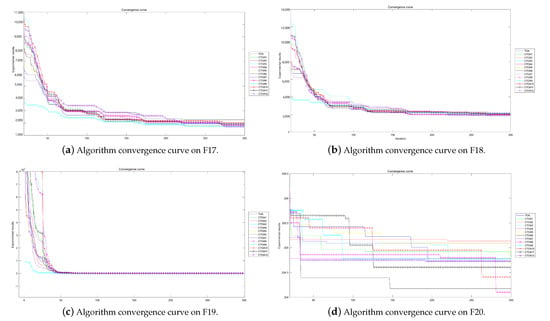

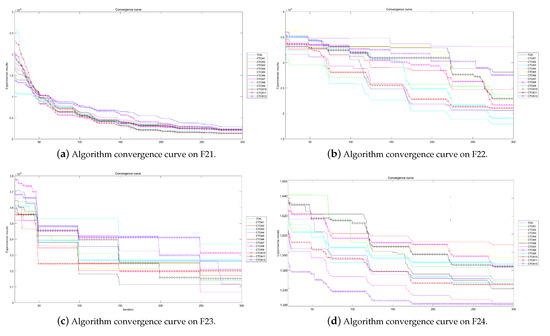

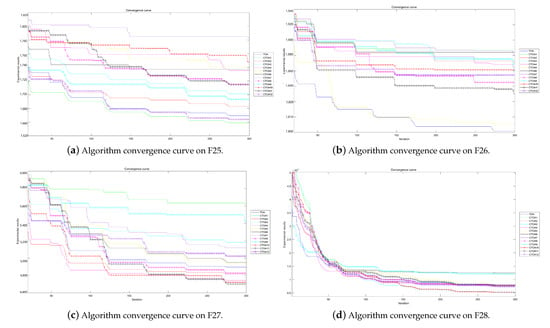

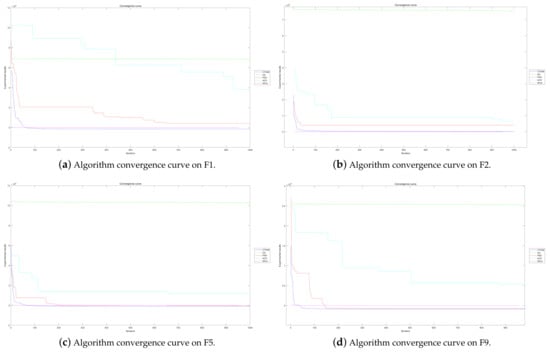

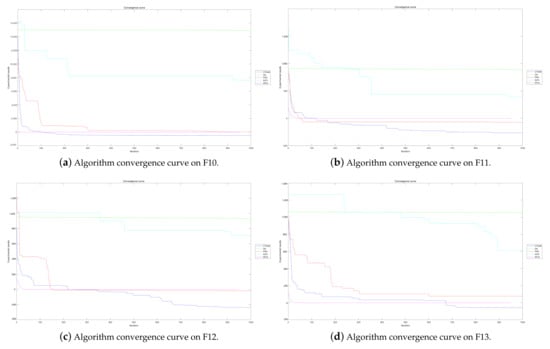

In this section, we run the CTOA presented in Table 4 at 30D, 50D, and 100D and record their convergence curves to demonstrate whether the CTOA algorithm has an advantage over the TOA in terms of convergence. Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 report the results of the algorithms in Table 4 running in 30D, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18 report the results in 50D, and Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25 report the results in 100D. The best fitness value obtained by different algorithms on the benchmark function is used to evaluate the algorithm’s performance in terms of convergence speed during the iterative visualization process.

Figure 5.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F1–F4 run in 30D.

Figure 6.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F5–F8 run in 30D.

Figure 7.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F9–F12 run in 30D.

Figure 8.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F13–F16 run in 30D.

Figure 9.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F17–F20 run in 30D.

Figure 10.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F21–F24 run in 30D.

Figure 11.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F25–F28 run in 30D.

Figure 12.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F1–F4 run in 50D.

Figure 13.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F5–F8 run in 60D.

Figure 14.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F9–F12 run in 50D.

Figure 15.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F13–F16 run in 50D.

Figure 16.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F17–F20 run in 50D.

Figure 17.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F21–F24 run in 50D.

Figure 18.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F25–F28 run in 50D.

Figure 19.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F1–F4 run in 100D.

Figure 20.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F5–F8 run in 100D.

Figure 21.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F9–F12 run in 100D.

Figure 22.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F13–F16 run in 100D.

Figure 23.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F17–F20 run in 100D.

Figure 24.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F21–F24 run in 100D.

Figure 25.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions F25–F28 run in 100D.

The experimental convergence curves also show that CTOA9 has obvious convergence compared to TOA and other algorithms using chaotic maps. CTOA9 achieves a faster convergence rate on most of the test functions, and after 300 iterations, the final fitness function results are also optimal. CTOA9 is not the fastest convergence speed in Figure 10d, Figure 13c and Figure 24a, but it is also faster than the other algorithms. On the unimodal function, there is only one global optimum of the benchmark function; thus, it is easier for the algorithm to search for the optimal position. Therefore, on the unimodal function F1–F5, all algorithms stagnate around iteration 150. On multimodal functions and composition functions, CTOA9 reaches the stagnation state later, and most algorithms reach the stagnation state before it, for example, at F8, F9, F14.

In addition, there is an “interesting” experimental phenomenon by observing the convergence curve of the CTOA9 algorithm running in 100D. That is, the convergence curves become similar, such as in Figure 19a,c and Figure 20b which means that the performance of CTOA and TOA in convergence tends to be consistent.

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Algorithms

From previous experiments, we can prove that CTOA9 is the best among all CTOAs. To accurately evaluate and draw conclusions regarding the quality of the proposed algorithm in terms of stagnation, exploration, and diversity, we conducted experiments to compare other algorithms of the same type. Therefore, we selected GA [3], PSO [2], ACO [7], and SFLA [8] and compared them with CTOA9. According to previous studies, the algorithm parameter settings are shown in Table 24.

Table 24.

The parameter settings for the relevant algorithm.

We selected some benchmark functions, and the convergence speeds of the algorithm on these functions are shown in Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28. On the unimodal functions F1, F2, F5, SFLA has the fastest convergence speed and the best fitness value. After about 50 iterations, CTOA9 converged and then stagnated. Among these algorithms, SFLA has the best performance on unimodal functions, and CTOA9 is slightly weaker than it. On multimodal functions F9–F14, CTOA9 stagnates after 700 iterations except for F9 and F10. GA and SFLA can converge in less than 100 iterations, but their fitness values are very poor. Although the convergence speed of CTOA is slow, the final fitness value is optimal among all algorithms. Similarly, CTOA9 also obtains the best fitness value on the mixture function F21–F23. In summary, although the convergence speed of CTOA9 is slow, it has a strong global exploration ability, can jump out of the local optimum, and continuously updates the optimal value.

Figure 26.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions.

Figure 27.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions.

Figure 28.

Algorithm convergence curves for benchmark functions.

Nonparametric statistical methods can help us compare the performance of different algorithms. Therefore, we conducted a Friedman test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test on CTOA9, GA, PSO, ACO, SFLA, and statistical values were obtained on the benchmark functions. The results of the Friedman test are shown in Table 25. The results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test are shown in Table 26. From Table 25, CTOA can achieve the best performance in the Friedman test. SFLA performance is slightly weaker than CTOA9. GA was the worst performer, ranking fifth. In addition, through Table 26, CTOA9 is significantly different from all other algorithms. In summary, through nonparametric statistical experiments, CTOA9 is the best in terms of overall performance.

Table 25.

Friedman ranking of different algorithms.

Table 26.

The results of the Wilcoxon test comparing CTOA with state-of-the art algorithms.

5. Real Problem: Power Generation Prediction

With the rapid development of the economy, people’s electricity consumption has increased, such that the huge electricity load has increased the requirements for power generation. Power generation prediction is critical for accurate decision making by electric utilities and power plants. For the feature data collected from the power plant, the relationship between each parameter is mutually influenced, and many features cannot be expressed by a simple functional relationship. Support vector machine (SVM) is a commonly used machine learning algorithm. The SVM model has unique advantages in reflecting the nonlinear relationship between parameters. The performance of SVM largely depends on the values of the selected hyperparameters. The penalty parameter c and the width parameter g play a decisive role in the classification results and prediction accuracy of SVM.

Cross-validation is often used to select hyperparameters, but this approach tends to consume a lot of computational resources and time. Because the metaheuristic algorithm performs well in random searches and iterations in the hyperparameter space, it is widely used in the hyperparameter optimization of SVM. The proposed CTOA algorithm can help us find the best combination of hyperparameters. To examine the performance of the proposed algorithm, we applied the proposed algorithm to an optimized power forecasting model and compared the results of the proposed optimal CTOA9 with GA, PSO, ACO, SFLA ACO. According to previous studies, the algorithm parameter settings are shown in Table 24.

The framework of this method is shown in Figure 29.

Figure 29.

The framework of the power prediction model.

Additionally, the prediction error used as the fitness function in this problem is shown in the following equation:

where m is the total number of training samples, and and are the actual and model predicted values. In order to evaluate the model more comprehensively, we also used as the evaluation standard, and its equation is shown below:

where is the true value, and is the predicted value.

All algorithms were used to optimize SVM parameters and are applied in power forecasting, and the obtained results are shown in the Table 27. Among the two selected evaluation indicators, the smaller RMSE is better, and the closer is to 1, the better. The final RMSE obtained by CTOA = 0.051033, which is the best among the six algorithms, 7.4% higher than the second PSO algorithm. The final = 0.96719 obtained by CTOA is very close to 1. It performs best among all algorithms. In summary, the newly proposed CTOA-SVM model performs best.

Table 27.

The results of different algorithms.

6. Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that the use of chaotic maps improves the performance of TOA in solving optimization problems. Specifically, the numerical statistics and convergence speed of CTOA are significantly better than that of TOA. The circle map is observed to have the most prominent effect on improving the algorithm’s performance, particularly in 50D. When the population position is initialized, the chaotic sequence generated by the circle map is used to replace the random initial sequence, which makes the population evenly distributed and expands the global search range. However, as the dimensions increase, the performance of TOA also improves, and its performance is comparable to that of CTOA in 100D. This implies that the advantages of using chaotic maps to improve TOA’s performance diminish in higher dimensions, and the performance of both TOA and CTOA tends to become average. This suggests that CTOA is more suited for optimization problems at lower dimensions, specifically in the range of 30–50D. Moreover, the increase in the number of variables in higher dimensions makes it difficult for chaotic maps to handle such complexity, leading to a reduction in performance improvement. Although CTOA9 is not significant to CTOA3 and CTOA7, it does not imply that CTOA9 performs poorly in the Wilcoxon test experiment. The Wilcoxon rank sum test is just a statistical method used to compare the differences between two samples, and its results are affected by many factors, which need to be fully considered in future research. In the convergence results, the fitness value of CTOA9 is still being updated, indicating that the algorithm still has more exploration capabilities when the iteration terminates (). In future research, it is necessary to increase the number of iterations so that the algorithm converges eventually, to fully evaluate the convergence speed.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a novel optimization algorithm called the chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm (CTOA). The use of chaotic maps increases the diversity of the initial population, leading to improved algorithm performance. The performance of CTOA was tested on 28 benchmark functions of CEC2013. The comparative experimental results showed that the improved CTOA using the circle map is better than the original TOA in both the accuracy and convergence speed of finding the optimal value. We conclude that the CTOA9 algorithm using the circle map outperforms other CTOAs and TOA in terms of optimal results and benchmark function convergence. We compared CTOA9 with famous state-of-the-art optimization algorithms, including GA, PSO, ACO, SFLA. The results demonstrated that CTOA9 is not only best on the Friedman ranking test and Wilcoxon test, but it also has the minimum error when applied to power generation prediction problems. In addition, the performance of CTOA based on a circle map is more outstanding in lower search space dimensions (30D and 50D), but as the dimension increases to 100D, the performance of CTOA and TOA become more similar. Therefore, the CTOA algorithm is more suitable for solving problems with lower search space dimensions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Y.W.; methodology, T.-Y.W. and A.S.; software, A.S.; formal analysis, J.-S.P.; investigation, T.-Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-Y.W., A.S. and J.-S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSO | particle swarm optimization |

| GA | genetic algorithm |

| WOA | whale optimization algorithm |

| GWO | grey wolf optimizer |

| SSA | salp swarm algorithm |

| TOA | tumbleweed optimization algorithm |

| CTOA | chaotic-based tumbleweed optimization algorithm |

| CMOV | chaotic multi-variate optimization |

| CPSO | chaotic particle swarm optimization |

| FCFA | Gauss map-based chaotic firefly algorithm |

| FSS | fish school search |

| CWOA | chaotic whale optimization algorithm |

| GSK | gaining sharing knowledge |

| CAOA | chaotic arithmetic optimization algorithm |

| HGS | hunger games search |

| RBFNN | radial basis function neural network |

| SGO | social group optimization |

| ICMIC | iterative chaotic map with infinite collapse |

| standard |

References

- Zhang, F.; Wu, T.Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R.; Ding, G.; Mei, P.; Liu, L. Application of quantum genetic optimization of LVQ neural network in smart city traffic network prediction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 104555–104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, F.; Walczak, B. Particle swarm optimization (PSO). A tutorial. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2015, 149, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Genetic Algorithm. In Evolutionary Algorithms and Neural Networks: Theory and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, J.; Khiyabani, F.M. A whale optimization algorithm (WOA) approach for clustering. Cogent Math. Stat. 2018, 5, 1483565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Gandomi, A.H.; Mirjalili, S.Z.; Saremi, S.; Faris, H.; Mirjalili, S.M. Salp Swarm Algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2017, 114, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar-Solanki, V.; Kumar Choudhary, S.; Selamat, A.; González-Crespo, R. Comparative Study on Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) and K-Means Clustering Approaches for Jobs Scheduling and Energy Optimization Model in Internet of Things (IoT); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eusuff, M.; Lansey, K.; Pasha, F. Shuffled frog-leaping algorithm: A memetic meta-heuristic for discrete optimization. Eng. Optim. 2006, 38, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Guo, X.; Tan, L. A self-Adaptive CNN with PSO for bearing fault diagnosis. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2021, 9, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malviya, S.; Kumar, P.; Namasudra, S.; Tiwary, U.S. Experience Replay-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dialogue Management Optimisation; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Houssein, E.H.; Saad, M.R.; Hussain, K.; Zhu, W.; Shaban, H.; Hassaballah, M. Optimal Sink Node Placement in Large Scale Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Harris’ Hawk Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 19381–19397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Chaudhury, S.; Panigrahi, B.K. Hybrid MPSO-CNN: Multi-level particle swarm optimized hyperparameters of convolutional neural network. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 63, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.Y.; Li, H.; Chu, S.C. CPPE: An Improved Phasmatodea Population Evolution Algorithm with Chaotic Maps. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.L.H.P.; Manoharan, M.K.; Pani, A.K.; Avala, R.R.; Chen, C.M. Gaussian Mutation–Spider Monkey Optimization (GM-SMO) Model for Remote Sensing Scene Classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Guo, J.; Ye, M.; Lv, J. Similarity Feature Construction for Matching Ontologies through Adaptively Aggregating Artificial Neural Networks. Mathematics 2023, 11, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xiao, P.; Zhai, R.; Sun, Y.; Wenbin, H.; Ji, W. Path Planning of Welding Robots Based on Developed Whale Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Control, Robotics and Cybernetics (CRC), Shanghai, China, 9–11 October 2021; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Lv, S.; Ning, J.; Wu, J.M.T. A Genetic Algorithm for the Waitable Time-Varying Multi-Depot Green Vehicle Routing Problem. Symmetry 2023, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.Y.; Chang, H.W.; Tu, C.J.; Yang, C.H. Improved binary PSO for feature selection using gene expression data. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2008, 32, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X. Complex ontology alignment for autonomous systems via the Compact Co-Evolutionary Brain Storm Optimization algorithm. ISA Trans. 2023, 132, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.L.; Wang, C.J. A GA-based feature selection and parameters optimizationfor support vector machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 2006, 31, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadeh, A.; Abualigah, L.; Elaziz, M.A.; Şahin, C.B.; Almazroi, A.A.; Omari, M. Augmented grasshopper optimization algorithm by differential evolution: A power scheduling application in smart homes. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 31569–31597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, R.; Kaveh, A.a. A Survey of chaos embedded meta-heuristic algorithms. Int. J. Optim. Civ. Eng. 2013, 3, 617–633. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabioun, R. Cuckoo optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 5508–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos Filho, C.J.A.; de Lima Neto, F.B.; Lins, A.J.C.C.; Nascimento, A.I.S.; Lima, M.P. A novel search algorithm based on fish school behavior. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Singapore, 12–15 October 2008; pp. 2646–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Rahnamayan, S.; Liu, Y.; Ventresca, M. Enhancing particle swarm optimization using generalized opposition-based learning. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 4699–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, G.G. Improved elephant herding optimization using opposition-based learning and K-means clustering to solve numerical optimization problems. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 1753–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamkar, R.; Das, P.; Namasudra, S. SCEOMOO: A novel Subspace Clustering approach using Evolutionary algorithm, Off-spring generation and Multi-Objective Optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 139, 110185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, D.; Martinović, G.; Brest, J. A population initialization method for evolutionary algorithms based on clustering and Cauchy deviates. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 60, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikolainen, I.; Neri, F.; Caraffini, F. Cluster-Based Population Initialization for differential evolution frameworks. Inf. Sci. 2015, 297, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.Y.; Hsiao, C.J.; Yang, C.H. Chaotic particle swarm optimization for data clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 14555–14563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ding, G.; Tu, L. Adaptive chimp optimization algorithm with chaotic map for global numerical optimization problems. J. Supercomput. 2022, 79, 6507–6537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.f.; Liu, S.y.; Huang, L.l. Particle swarm optimization with chaotic opposition-based population initialization and stochastic search technique. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2012, 17, 4316–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, G. Elite Chaotic Manta Ray Algorithm Integrated with Chaotic Initialization and Opposition-Based Learning. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.H.; Yun, G.J.; Yang, X.S.; Talatahari, S. Chaos-enhanced accelerated particle swarm optimization. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2013, 18, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Singh, S. An improved butterfly optimization algorithm with chaos. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 32, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M.; Arora, S. Chaotic grey wolf optimization algorithm for constrained optimization problems. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2018, 5, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Zheng, G.; Khan, M.K. An effective memetic differential evolution algorithm based on chaotic local search. Inf. Sci. 2011, 181, 3175–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.S.; Yang, Q.; Shieh, C.S.; Chu, S.C. Tumbleweed Optimization Algorithm and Its Application in Vehicle Path Planning in Smart City. J. Internet Technol. 2022, 23, 927–945. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, G.I.; Darwish, A.; Hassanien, A.E. A new chaotic multi-verse optimization algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2018, 30, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.S.; Ke, X.T.; Liao, J.G.; Shen, Y.J. DSLC-FOA: Improved fruit fly optimization algorithm for application to structural engineering design optimization problems. Appl. Math. Model. 2018, 55, 314–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A.; Elhoseny, M.; Hassanien, A.E.; Gabel, T.; Kumar, A. Intelligent Bézier curve-based path planning model using Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 4745–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, A.; Mahdipour Moghanni, R.; Javadi, S. Optimum design of large steel skeletal structures using chaotic firefly optimization algorithm based on the Gaussian map. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 60, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidova, L.A.; Gorchakov, A.V. A study of chaotic maps producing symmetric distributions in the fish school search optimization algorithm with exponential step decay. Symmetry 2020, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Guo, Q. Modified whale optimization algorithm based on tent chaotic mapping and its application in structural optimization. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 3703–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.; Ganesh, T.; Mohamed, A.W. Chaotic gaining sharing knowledge-based optimization algorithm: An improved metaheuristic algorithm for feature selection. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 9505–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Wang, J.S.; Hao, W.K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M. Chaotic arithmetic optimization algorithm. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 16718–16757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onay, F.K.; Aydemir, S.B. Chaotic hunger games search optimization algorithm for global optimization and engineering problems. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 192, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wang, T.; Yang, H.; Meng, C.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, L. The Performance of Electronic Current Transformer Fault Diagnosis Model: Using an Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm and RBF Neural Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoxi, L.; Lifang, H.; Songwei, H.; Bin, H.; Changzhou, Y.; Lingpan, D. An improved bald eagle algorithm based on Tent map and Levy flight for color satellite image segmentation. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A. Chaotic Social Group Optimization for Structural Engineering Design Problems. J. Bionic Eng. 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatak, S.C.; Rao, S.S. Logistic map: A possible random-number generator. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 3670–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, R.L. A piecewise linear model for the zones of instability of an area-preserving map. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1984, 10, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.A.; Oliva, D.; Ewees, A.A.; Lu, S. Feature selection based on improved runner-root algorithm using chaotic singer map and opposition-based learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Z.; Zhou, Y. Image encryption using 2D Logistic-adjusted-Sine map. Inf. Sci. 2016, 339, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driebe, D.J. The bernoulli map. In Fully Chaotic Maps and Broken Time Symmetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.H.; Bak, P.; Bohr, T. Complete devil’s staircase, fractal dimension, and universality of mode-locking structure in the circle map. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.D.; Whitley, D.C. Chaos in the cubic mapping. Math. Model. 1983, 4, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, G.I.; Darwish, A.; Hassanien, A.E. A new chaotic whale optimization algorithm for features selection. J. Classif. 2018, 35, 300–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, K.; He, Y.; Yu, M. Color image encryption using three-dimensional sine ICMIC modulation map and DNA sequence operations. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2017, 27, 1750171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Engelbrecht, A.; Epitropakis, M.G. Benchmark Functions for CEC’2013 Special Session and Competition on Niching Methods for Multimodal Function Optimization; RMIT University, Evolutionary Computation and Machine Learning Group: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).