Abstract

The notion of ordinal definability and the related notions of ordinal definable sets (class ) and hereditarily ordinal definable sets (class ) belong to the key concepts of modern set theory. Recent studies have discovered more general types of sets, still based on the notion of ordinal definability, but in a more blurry way. In particular, Tzouvaras has recently introduced the notion of sets nontypical in the Russell sense, so that a set x is nontypical if it belongs to a countable ordinal definable set. Tzouvaras demonstrated that the class of all hereditarily nontypical sets satisfies all axioms of and satisfies . In view of this, Tzouvaras proposed a problem—to find out whether the class can be separated from by the strict inclusion , and whether it can also be separated from the universe of all sets by the strict inclusion , in suitable set theoretic models. Solving this problem, a generic extension of the Gödel-constructible universe , by two reals , is presented in this paper, in which the relation is fulfilled, so that is a model of strictly between and the universe. Our result proves that the class is really a new rich class of sets, which does not necessarily coincide with either the well-known class or the whole universe . This opens new possibilities in the ongoing study of the consistency and independence problems in modern set theory.

MSC:

03E35

1. Introduction

We recall that a set X is ordinal definable if X can be defined by a formula with ordinals as parameters in the universe of all sets. The class of all ordinal definable sets is denoted by . Further, a set X is hereditarily ordinal definable if X itself, as well as all elements of X, all elements of elements of X, etc., belong to . In other words, it is required that , where , the transitive closure of X, is the least transitive set containing X, and a set Y is transitive if . The class of all hereditarily ordinal definable sets is denoted by . To conclude,

See more on these fundamental notions of modern set theory in [1] (Chapter 13) or [2] (Section II.8), or [3] as the original reference. In particular, it is known that is a transitive class and a model of the set theory (with the axiom of choice ). In general, classes and , as well as Gödel’s class of all constructible sets, have played a key role in modern set theory since its early days.

Research in recent years has brought to the fore some other notions of definability, such as algebraic definability studied in [4,5,6], blurry definability of [7], and finally nontypicality in the sense of Russell, introduced by Tzouvaras [8,9]. Our paper is dedicated to this last concept. By Tzouvaras, a set x is nontypical, for short , if it belongs to a countable ordinal definable set Y. A set x is hereditarily nontypical, for short , if it itself, all its elements, elements of elements, and so on, are all nontypical—in other words, it is required that the transitive closure satisfy . To conclude,

Tzouvaras [8,9] connected these notions with some philosophical and mathematical ideas of Bertrand Russell and works of van Lambalgen [10] et al. on the concept of randomness. They contribute to the ongoing study of important classes of sets in the set theoretic universe which themselves satisfy the axioms of set theory, similarly to Gödel’s class and the class . The class is transitive and, as shown in [9], satisfies all axioms of (the axiom of choice AC not included).

It is customary in modern set theory (see e.g., [1,2,11,12]) that any new class of sets is checked in terms of relations with already known classes. In that respect, Tzouvaras [9] established the non-strict inclusion , and proposed a problem: to find out whether the class can be separated from by the strict inclusion , and can also be separated from the universe of all sets by the strict inclusion , in suitable set theoretic models.

Problem 1

(Tzouvaras [9], 2.15). Does there exist a model of in which the class satisfies the strict double inclusion ?

The following theorem answers this important problem in the affirmative.

Theorem 1.

Let be the Cohen forcing for adding a generic real to . There is a forcing notion , which consists of Silver trees, and such that if a pair of reals is -generic over then it is true in that

This is the main conclusion of this paper: the relation (1) provides the double separation property required. Note that the class by (1) satisfies , not merely , in the model of the theorem, which is an additional advantage of our result.

To prove the theorem, we make use of a forcing notion introduced in [13] in order to define a generic real whose -equivalence class is a lightface (hence OD) set of reals with no OD element. (We recall that the equivalence relation is defined on so that iff for all but finite k.) This property of is responsible for a -generic real a to belong to , and ultimately to , in . This will be based on some results on Silver trees and Borel functions in Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4. The construction of in is given in Section 5 and Section 6. The proof that in follows in Section 8.

The inverse inclusion in will be proved in Section 9 on the basis of our earlier result [14] on countable OD sets in Cohen-generic extensions.

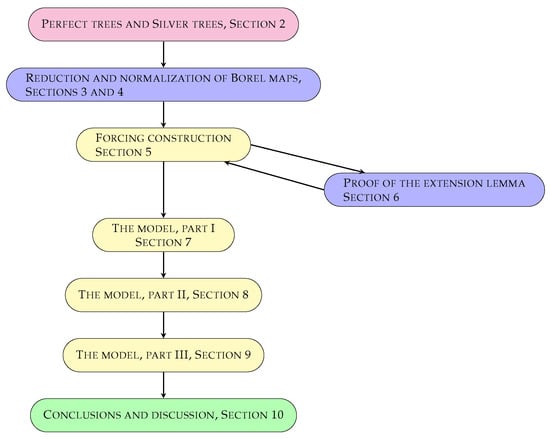

See flowchart of the proof of Theorem 1 on page 3, Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proof of Theorem 1.

The reader envisaged is assumed to have some knowledge of the pointset topology of the Baire space (we give [15] and [1] [Chapter 11] as references) along with some basic knowledge of forcing and Gödel’s constructibility (we give [1,2,16] as references).

2. Silver Trees

The proof of Theorem 1 in this paper will involve a forcing notion which consists of Silver trees. Here, we recall the relevant notation.

By we denote the set of all tuples (finite sequences) of terms , including the empty tuple . The length of a tuple s is denoted by , and (all tuples of length n). A tree is a perfect tree, symbolically , if it has no endpoints and isolated branches. In this case, the set

of all branches of T is a perfect set in If , then

is a portion of T. A tree is clopen in T iff it is equal to the union of a finite number of portions of T. This is equivalent to being clopen in as a pointset in .

Definition 1.

A tree is a Silver tree, symbolically , if there is an infinite sequence of tuples such that T consists of all tuples of the form

and their sub-tuples, where and .

Note that the stem of any tree is equal to the largest tuple with , and consists of all infinite sequences where , . We further put

the -th splitting level of a Silver tree T. In particular, .

Action. Let If is another tuple of length , then the tuple of the same length is defined by (addition modulo 2) for all , but whenever . If , then we just define .

If then similarly for , but for . If , then the sets

are shifts of the tree T and the set X accordingly.

According to (ii) of the next lemma (Lemma 3.4 in [17]), all portions , of the same level, of any Silver tree are shifts of each other, or saying it differently, T can be recovered from any its portion. This is not true for arbitrary trees in , of course.

Lemma 1.

- (i)

- If and then and .

- (ii)

- If and then .

Refinements. Assume that , , . We define (the tree S n-refines T) if and for all . This is equivalent to ( and) for all , of course.

Then, is equivalent to , and implies (and ).

In addition, if then is equivalent to .

Lemma 2.

Assume that , and . Then, there is a unique tree such that and

If in addition U is clopen in T then S is clopen in T, as well.

Proof.

Define a tree S so that , and if then, following Lemma 1(ii), ; in particular . To check that , we can easily compute the according tuples to fulfill Definition 1. Namely, as , we have , hence the length satisfies . Then, we have

and Definition 1 for S is satisfied with these tuples . In addition, if U is clopen in T (i.e., U is a finite union of portions in T), then clearly so is S. □

Lemma 3

([17], Lemma 4.4). Let be a sequence of trees in . Then, .

Proof

(sketch). By definition, we have for all . Then, one easily computes that for all n. □

3. Reduction of Borel Maps to Continuous Ones

A classical theorem claims that in Polish spaces every Borel function is continuous on a suitable dense set. It is also known that a Borel map defined on is continuous on a suitable Silver tree. The next lemma combines these two results.

Our interest in Borel functions defined on is motivated by further applications to reals in generic extensions of the form , where is a -generic real for a certain forcing notion , whereas is just a Cohen generic real. These applications will be based on the fact that any real in such an extension can be represented in the form , where is a Borel map coded in the constructible universe (Corollary 2 below in Section 5).

In the remainder, if (a tuple of natural numbers), then we define , a clopen Baire interval in the Baire space

Lemma 4.

Let and be a Borel map. Then, there is a Silver tree and a dense set such that f is continuous on

Proof.

By the abovementioned classical theorem (Theorem 8.38 in Kechris [15]), there exists a dense set such that f is already continuous on Z. It remains to define a Silver tree and a dense set such that This will be our goal.

By the choice of Z we have , where each is open dense.

Let us fix an enumeration of the cartesian product We shall define a sequence of Silver trees and tuples satisfying the following three conditions (a)–(c):

- (a)

- , as in Lemma 3;

- (b)

- if then is clopen in (see Section 2);

- (c)

- and , for all k.

At step 0 we already have by (a).

Assume that a tree has already been defined. Let .

Consider any tuple As is open dense, there is a tuple and a Silver tree , clopen in (for example, a portion in ) such that and . According to Lemma 2, there exists a Silver tree , clopen in along with A, such that , so by construction.

Now, take another tuple and similarly find and a Silver tree , clopen in , such that and . Once again, there is a Silver tree , clopen in and such that .

We iterate this construction over all tuples -shrinking trees and extending tuples in We obtain a Silver tree , clopen in , and a tuple that and . Take . This completes the inductive step.

As a result we obtain a sequence of Silver trees , and tuples (), which really satisfy conditions (a)–(c).

We put ; then by (a) and Lemma 3, and .

If then let . We claim that is an open dense set in Indeed, let Consider any k such that that and . By construction, we have . Thus the set is dense and .

To check , let ; we show that . Let and , in particular , so for some k with . However, by (c), and at the same time obviously . Therefore, , as required. □

Corollary 1.

Suppose that and be a Borel map. Then there is a Silver tree such that f is continuous on

We add the following result that belongs to the folklore of the Silver forcing. See Corollary 5.4 in [18] for a proof.

Lemma 5.

Assume that and is a continuous map. Then there is a Silver tree such that f is either a bijection or a constant on .

4. Normalization of Borel Maps

In this section, we continue studying the behavior of Borel maps defined on modulo restrictions on products of Silver trees and dense sets. We work in the context of the following definition of normalization, and the following Lemma 6 will be of key importance in the applications to the genetic extensions below in Section 6.

Definition 2.

A map is normalized on a tree for a set of trees if there exists a dense set such that f is continuous on and

- −

- either(I)there are tuples such that for all and , where, we remind,

- −

- or(II) for all and

Lemma 6.

Assume that and is a Borel map. Then there exists a set of trees , such that for all n and f is normalized on for .

Proof.

First of all, according to Lemma 4, there is a Silver tree and a dense set such that f is continuous on . Since any dense set is homeomorphic to we can w.l.o.g. assume that and . In other words, we just suppose that f is already continuous on

Assume that option (I) of Definition 2 does not take place, that is

- (∗)

- if is a dense set, and , then there exist reals and such that .

We shall construct Silver trees and a dense set satisfying (II) of Definition 2, that is, in our context, the negative relation will be fulfilled for all and To maintain the construction, let us fix an arbitrary enumeration

Further, auxiliary Silver trees () and tuples () will be defined, satisfying the following conditions (a)–(c).

- (a)

- as in Lemma 3, for each ;

- (b)

- for all ;

- (c)

- , , , and for all reals and .

At step 0 of the construction, we input for all n, according to (a).

Assume that and all Silver trees are already defined. We input for all , by (b). (The number is defined by (6).)

To define the trees and , we put , .

Case 1: . Take any pair of tuples , and any reals and Consider any real not equal to . Let us say , where . As f is continuous, there is a tuple and a Silver tree such that , , and for all and . It is also clear that

is a Silver tree containing , and for all . According to Lemma 2, there exist Silver trees and , such that and . It follows by construction that for all and .

Now, consider another pair of tuples , . We similarly obtain Silver trees and , and a tuple such that and for all and . In this case, we have and , so that what has already been achieved in the previous step is preserved.

We iterate over all pairs of , , by -shrinking trees and extending tuples in at each step. This results in a pair of Silver trees and a tuple such that and for all reals and . Now, to fulfill (c), take , and Recall that here .

Case 2: . Here, the construction somewhat changes, and hypothesis (∗) will be used. We claim that there exist:

- (d)

- a tuple and a Silver tree such that and for all , . (This is equivalent to (c) as .)

Take any pair of tuples , where as above. Thus, , by Lemma 1(ii). According to (∗), there are reals and satisfying , or equivalently, .

Similarly to Case 1, we have for some and . By the continuity of f, there is a tuple and a Silver tree , clopen in , such that , , and but for all and . Lemma 2 gives us a Silver tree , clopen in as well, such that — and then . Therefore, holds for all and by construction.

Having considered all pairs of tuples , we obtain a Silver tree and a tuple such that and for all and . Now, to fulfill (d), take and . This concludes Case 2.

To conclude, we have for each n a sequence of Silver trees , along with tuples (), and these sequences satisfy the requirements (a)–(c) (equivalent to (d) in case ).

We put for all n. Then, by Lemma 3, and .

If and , then let . The set is then open dense in Indeed, if , then we take k such that ; then by construction. Therefore, is a dense set. Now, to check property (II) of Definition 2, consider any ; we claim that .

Indeed, by construction we have , i.e., , where , so that . Now, directly follows from (c) for this k, since and . □

5. The Forcing Notion for Theorem 1

In this section, we define a forcing notion , , involved in the proof of Theorem 1. This will be a rather lengthy construction, and we begin with auxiliary material.

We use letters and to denote effective (lightface) projective classes.

Using the standard encoding of Borel sets, as e.g., in [19], or [20] [§ 1D], we make use of coding systems for Borel functions and

- (A)

- We fix a coding system for Borel functions which includes a -set of codes , and for each code , a certain Borel function coded by We assume that each Borel function has some code, and there is a relation and a relation such that for all and it holds .

- (B)

- We fix a coding system for Borel functions that includes a -set of codes , and for each code , a Borel function coded by r, such that each Borel function has some code, and there is a relation and a relation such that for all and it holds .

If , then denotes the set of all trees of the form , where and , i.e., the closure of w.r.t. both shifts and portions.

The following construction is maintained in . We define a sequence of countable sets satisfying the following conditions 1°–6°.

- 1°

- Each is countable, consists of a single tree

We then define , . These sets are obviously closed with respect to shifts and portions, that is, and .

- 2°

- For every , there is a tree .

Let be the sub-theory of ZFC, containing all axioms except the power set axiom (and with the wellorderability principle instead of AC), and additionally containing an axiom asserting the existence of the power set . This implies the existence of for any countable X, the existence of and , as well as the existence of continual sets like or .

By we denote the smallest model of of the form containing the sequence , in which and all sets are countable.

- 3°

- If a set is dense in , and , then , meaning that there is a finite set such that .

- 4°

- If a set is dense in , and belong to , then , meaning that there is a finite set such that .

Given that , this is automatically transferred to all trees , as well. It follows that D remains pre-dense in .

To formulate the next property, we fix an enumeration

in , which (1) is definable in , and (2) involves each value in being taken uncountably many times.

- 5°

- If , then there is a tree such that and:

- is normalized for on in the sense of Definition 2, and

- is continuous and either a bijection or a constant on .

- 6°

- The sequence is -definable in .

The construction 1°–6° goes on as follows. We work in .

We first define to obey 1°.

Now, suppose that

- (†)

- , the subsequence is defined and satisfies 1°, 2° below , and the sets (for ), , are defined as above.

The induction step of the construction is based on the following lemma.

Lemma 7

(in , see the proof in Section 6). Under the assumptions of (†), there is a countable set satisfying conditions 2°, 3°, 4°, 5°.

To accomplish the construction on the base of the lemma, we take to be the smallest, in the sense of the Gödel wellordering of , of those sets that exist by Lemma 7. Since the whole construction is relativized to , requirement 6° is also met.

We put for all , and .

The next result, in part related to the countable chain condition, or CCC for brevity, is a fairly standard consequence of 3° and 4°, see for example [13] (6.5), [18] (12.4), or [21] (Lemma 6); we will omit the proof. Recall that a forcing notion satisfies CCC iff every antichain is finite or countable.

Lemma 8

(in ). The forcing notion belongs to , satisfies and satisfies CCC in . The product satisfies CCC in , as well.

Corollary 2.

- (i)

- If a real is -generic over and , then there is a Borel map with a code such that .

- (ii)

- If a pair is -generic over and then there is a Borel map with a code such that .

Proof. (i)

By the Gödel constructibility theory, there is an ordinal such that y is the th element of in the sense of the canonical wellordering of . However, the forcing notion preserves cardinals by Lemma 8, and hence . Finally, as , it is known that the map

is with a parameter by [20], Theorem 2.6(ii), and, hence, the map (9) is Borel with a code in , as required.

The proof of (ii) is similar. The forcing notion satisfies CCC since so does , whereas is countable. □

Lemma 9

(in ). Assume that . If is a Borel map then there is a tree , , such that g is either a bijection or a constant on .

If is a Borel map, then there is an ordinal and a tree , , such that f is normalized for on .

Proof.

By the choice of the enumeration (8) of triples in there is an ordinal such that and , , . Now, we refer to 5°. □

6. Proof of the Extension Lemma

Proof

(proof of Lemma 7). This section is entirely devoted to the proof of Lemma 7.

We work in under the assumptions of (†) above.

We first define a set of Silver trees satisfying 2°, 3° 4° then further narrowing of the trees will be performed to also satisfy 5°. This involves a splitting/fusion construction known from our earlier papers, see [13] (§ 4), [17] (§ 9–10), [18] (§ 10), and to some extent from the proof of Lemma 6 above.

We fix a bijection . We also fix enumerations

of the set of all sets open dense in , and the set of all sets open dense in .

The construction of the trees is organized in the form , where the Silver trees satisfy the following requirements (a)–(d):

- (a)

- We have as in Lemma 3 for each ;

- (b)

- if then for some n;

- (c)

- each is a -collage over .

Here, a Silver tree T is a -collage over [17,18] when for each tuple where . Then 0-collages are just trees in , and every -collage is a -collage as well, since .

- (d)

- If , , , (integers), , (tuples of length, resp., ), , then the tree belongs to and the pair belongs to . — It follows that and in the sense of 3°, 4° of Section 5.

To begin the inductive construction of the trees , we assign so that , to obtain (b). Now, let us maintain the step ; it continues simultaneously for all n. Thus, suppose that , and all Silver trees are defined and are -collages over .

Let . If , then put for all n.

Now, assume that Put for all .

It takes more effort to define and . Let , . To begin with, we input and . These -collages are the initial values for the trees and , to be -shrunk in a finite number of substeps (within the step ), each substep corresponding to a pair of tuples and .

Namely, let , be the first such pair. The trees , belong to as , are -collages over . Therefore, by the open density there exist trees such that the pair belongs to and . Now, Lemma 2 gives us Silver trees and satisfying , . Moreover, by Lemma 1, S and T still are -collages over since is closed under shifts by construction. To conclude, we have defined -collages over , satisfying , , , , and . We reassign the “new” and to be equal to resp. .

Applying this -shrinking procedure consecutively for all pairs of tuples and , we eventually (after finitely many substeps according to the number of all such pairs) obtain a pair of -collages and over , such that for every pair of tuples and , we have and , so conditions (c) and (d) are satisfied.

Having defined, in , a system of Silver trees satisfying (a)–(d), we then put for all n. Those are Silver trees by Lemma 3. The collection satisfies 2° of Section 5 by (b).

To check condition 3° of Section 5, let be dense in , and . We can w.l.o.g. assume that D is open dense; if not, then replace T by . Then, for some j, and for some M by construction. Now, consider any index k such that for as above and any . Then, we have by construction, and by (d), thus, , as required.

Condition 4° is verified similarly.

It remains to somewhat shrink all trees to also fulfill 5°. We still work in .

Recall that an enumeration , parameter-free definable in , is fixed by (8) in Section 5. We suppose that the tree belongs to . (If not, then we are not concerned about 5°.) Consider, according to 2°, a tree satisfying . Using Corollary 1 and Lemma 5 in Section 3, and Lemma 6, we shrink each tree to a tree , so that the function is normalized on for and is continuous and either a bijection or a constant on . Take as the final and as to fulfill 5°. □

7. The Model, Part I

We use the product of the forcing notion defined in Section 5 and satisfying conditions 1°–6° as above, and the Cohen forcing, here in the form of , to prove the following more explicit form of Theorem 1.

Theorem 2.

Let a pair of reals be -generic over . Then,

- (i)

- is not , and, moreover, in

- (ii)

- belongs to , and, moreover, in

- (iii)

- does not belong to , and, moreover, in

We prove Claim (i) of the Theorem 2 in this section. The proof is based on several lemmas. According to the next lemma, it suffices to prove that in .

Lemma 10.

.

Proof.

By the product forcing theorem, is a Cohen generic real over . It follows by a standard argument based on the full homogeneity of the Cohen forcing that if is in , then and H is in .

Now, prove the implication by induction on the set-theoretic rank of . Since each set consists only of sets of strictly lower rank, it is sufficient to check that if a set satisfies and in , then and . Here, we can assume that, in fact, , since allows an OD wellordering and hence an OD bijection onto . However, in this case, and H is in by the above, as required. □

Lemma 11

(Lemma 7.5 in [13]). is not in .

Proof.

Suppose towards the contrary that is in . Yet, is a -generic real over , so the contrary assumption is forced. In other words, there is a tree with and a formula with ordinal parameters, such that if is -generic over then a is the only real in satisfying . Let . Then, the tuples and belong to T, and either or . Let, say, . Let and , so that all three strings , , belong to and . As the forcing is invariant under the action of , the real is -generic over , and . We conclude that it is true in that is still the only real in satisfying . However, it is clear that ! □

Lemma 12.

If is a real, then b is not in .

Proof.

It follows from Corollary 2(i) that for some Borel function with a code . Now, by Lemma 9, there is a tree such that and is a bijection of a constant. If h is a bijection, then in since otherwise , contrary to Lemma 11. If h is a constant, so that there is a real such that for all , then , contrary to the choice of b. □

Lemma 13.

If , then X is not in .

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that , , and X is in . Let t be a -name for X. Then a condition (a Silver tree) -forces

over . Say that t splits conditions if there is an ordinal such that S forces but T forces or vice versa; let be the least such ordinal .

We claim that the set

is dense in above . Indeed, let be subtrees of . If t splits no stronger pair of trees , in , then easily both S and T decide for every ordinal , a contradiction with the choice of . Thus, D is indeed dense.

Let, in , be a maximal antichain; A is countable in by Lemma 8, and hence the set is countable in . We claim that

- (‡)

- the intersection does not belong to .

Indeed, otherwise, there is a tree , which -forces that . (The sets are identified with their names.)

By the countability of there is an ordinal such that , , and . We can w.l.o.g. assume that , for if not then we further increase below accordingly. Let . The trees and belong to along with , and hence there are trees with and . Clearly, , so that we have for a finite set by 4° of Section 5. Now, take reals and both -generic over . Then, there is a pair of trees such that and . The interpretations and are then different on the ordinal since . Thus, the restricted sets and differ from each other. In particular, at least one of is not equal to However, by construction, hence this contradicts the choice of and completes the proof of (‡).

Recall that and is countable in . It follows that b can be considered as a real, so we conclude that b is not OD in by Lemma 12 and (‡).

However, where X is OD and , hence W is OD in and b is OD in . The contradiction obtained ends the proof. □ (Lemma 13)

Now, Theorem 2(i) immediately follows from Lemma 10 and Lemma 13.

8. The Model, Part II

Here, we establish Claim (ii) of Theorem 2. To prove , it suffices to show that itself belongs to , and then make use of the fact that by Gödel every set has the form , where F is an OD function.

Further, to prove , it suffices to check that the set

(which is a countable set) is an OD set in . According to 6°, it suffices to establish the equality

Note that every set is pre-dense in ; this follows from 3° and 5°, see, for example, Lemma 6.3 in [13]. This immediately implies for each . Yet, all sets are invariant w.r.t. shifts by construction. Thus, we have the relation ⊆ in (14).

To prove the inverse inclusion, assume that a real belongs to the right-hand side of (14) in . It follows from Corollary 2(ii) that for some Borel function with a code .

Assume to the contrary that.

Since is a -generic real over by the forcing product theorem, this assumption is forced, so that there is a tuple such that

whenever a real is -generic over . (Recall that .) Let H be the canonical homomorphism of onto . We input for Note that H preserves the -genericity, and hence

whenever is -generic over . Note that f also has a Borel code in , so that .

It follows from Lemma 9 that there is an ordinal and a tree , on which f is normalized for , and which satisfies . Normalization means that, in , there is a dense set satisfying one of the two options of Definition 2. Consider a real (a -code for X in ) such that , where is a fixed recursive enumeration of tuples.

Case 1: there are tuples such that for all points and . In other words, it is true in that

However, this formula is absolute by the Shoenfield theorem, so it is also true in . Take (recall: ) and any real , -generic over . Then, , because is a dense set with a code from . Thus , which contradicts (16).

Case 2: for all and By the definition of , this implies for all and and this again contradicts (16) for .

The resulting contradiction in both cases refutes the contrary assumption above and completes the proof of Claim (ii) of Theorem 2.

9. The Model, Part III

Here, we prove Claim (iii) of Theorem 2. We make use of the following result that belongs to a series of results on countable and Borel OD sets in Cohen and some other generic extensions in [14].

Lemma 14.

Let be Cohen-generic over a set universe Then, it holds in that if is a countable OD set then More generally, if in , then it holds in that if is a countable set then

Proof.

The pure OD case is Theorem 1.1 in [14]. The proof of the general case does not differ, q is present in the flow of arguments as a passive parameter. □

Lemma 14 admits the following extension for the case . Here, naturally means sets definable by a formula containing a and ordinals as parameters.

Corollary 3.

Assume that and a real is Cohen-generic over . Then, it holds in that if and is a countable set then .

Proof.

As the Cohen forcing is countable, there is a set , countable in and such that if belong to , then for some . Then, Y is countable and in , so the projection of the set A will also be countable and in . We have by Lemma 14. (The set Y here can be identified with .) Hence, each is in .

However, if and , then , hence w is in by the above. Moreover, by the choice of Y, it holds in that f is the only element in A satisfying . Therefore, in . We conclude that . □

Proof

(Claim (iii) of Theorem 2). We prove an even stronger claim

in by induction on the set-theoretic rank of sets . Here, naturally means all sets hereditarily , the latter means all elements of countable sets in .

Since each set consists only of sets of strictly lower rank, to prove (18), it is sufficient to check that if a set satisfies and in , then . Here, we can assume that in fact , since allows an wellordering. Thus, let . Additionally, since , we have, in , a countable set containing H. However, by Corollary 3. This implies as required. □

This ends the proof of Theorem 2 as a whole and the proof of Theorem 1.

10. Conclusions and Discussion

In this study, different descriptive set theoretic and forcing tools are employed to define a generic extension of in which the class of all hereditarily nontypical sets is a model of (not merely ), separated from the class of all hereditarily nontypical sets and from the universe of all sets by the strict double inequality . This is the content of our main result, Theorem 1, and this solves a problem proposed in [9]. This result demonstrates that the class has its own merits and deserves further special study.

As for possible applications, this research can facilitate the ongoing research of different aspects of definability in modern set theory. Let us briefly present three such lines of research.

1. Tzouvaras [9] and Fuchs [7] (in terms of blurry definability) pursued a more general approach to nontypical sets. Namely, if is a cardinal, then let (-nontypical sets) contain all sets x which belong to ordinal definable sets Y of cardinality . Accordingly, let (hereditarily -nontypical sets) contain all sets x satisfying , as usual. Then, , of course, whereas coincides with the class of hereditarily algebraically definable sets in [6] and coincides with hereditarily ordinal definable sets as in Section 1 above. All classes satisfy , and we obviously have

for . This naturally leads to the following questions considered in [7,9]:

- (1)

- characterize cardinals satisfying strictly;

- (2)

- find out what forms of the axiom of choice are true in for different ;

- (3)

- investigate the nature of classes in different generic models and large cardinal models.

2. Another model, in which is strictly between and the universe but does not satisfy the axiom of choice unlike the model if Theorem 1, was introduced in [22]. It was briefly considered in [7,9] in the context of nontypical sets. This model extends by an infinite sequence of reals generic in the sense of the Jensen forcing [21], so that it is true in that the whole countable set of those reals is a lightface , hence OD, set that has no OD elements. In particular, as noted in [9], each belongs to , thus in such a model . On the other hand, the generic sequence itself does not belong to in [7], so that is a prover subclass of the set universe in . Yet the principal flaw of such a model is that its class fails to satisfy the axiom of choice AC (unlike the class of the model defined for Theorem 1). Thus, is a less worthy solution of Problem 1 in the Introduction.

3. Recall that if x is a Cohen real over , then in by Lemma 14. The following problem highlights another aspect of non-typicality in Cohen extensions.

Problem 2.

Is it true in generic extensions of by a single Cohen generic real that a countable OD set of any kind necessarily consists only of OD elements, and hence holds?

This is open even for finite OD sets. A more advanced techniques for studying Cohen extensions as in this paper (Section 9) or in [23] could be useful here.

Furthermore, it is not that obvious to expect the positive answer. Indeed, the problem solves in the negative for Sacks and some other generic extensions even for pairs. For instance, if x is a Sacks-generic real over then it is true in that there is an unordered pair of sets of reals such that themselves are non-OD sets. See [24] for a proof of this rather surprising result originally by Solovay.

4. It would be interesting to give any substantial treatment of topics related to definability (including ordinal definable and nontypical sets) in the frameworks of alternative set theories like recently introduced finitely supported mathematics FSM [25] or more classical and well-known ZFA with atoms [16] (Chapter 7), [26] (Chapter 7).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and V.L.; methodology, V.K. and V.L.; validation, V.K.; formal analysis, V.K. and V.L.; investigation, V.K. and V.L.; writing original draft preparation, V.K.; writing review and editing, V.K. and V.L.; project administration, V.L.; funding acquisition, V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. The study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their thorough review and highly appreciate the comments and suggestions, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jech, T. Set Theory, The Third Millennium Revised and Expanded ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. xiii + 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunen, K. Set Theory; Studies in Logic: Mathematical Logic and Foundations; College Publications: London, UK, 2011; Volume 34, pp. viii + 401. [Google Scholar]

- Myhill, J.; Scott, D. Ordinal definability. In Axiomatic Set Theory Proceedings Symposium Pure Mathematics Part I; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1971; Volume 13, pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G.; Gitman, V.; Hamkins, J.D. Ehrenfeucht’s lemma in set theory. Notre Dame J. Formal Logic 2018, 59, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Groszek, M.J.; Hamkins, J.D. The implicitly constructible universe. J. Symb. Log. 2019, 84, 1403–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamkins, J.D.; Leahy, C. Algebraicity and implicit definability in set theory. Notre Dame J. Formal Logic 2016, 57, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuchs, G. Blurry definability. Mathematics, 2021; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvaras, A. Russell’s typicality as another randomness notion. Math. Log. Q. 2020, 66, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzouvaras, A. Typicality á la Russell in Set Theory. ResearchGate Preprint. To appear in Notre Dame J. Form. Logic. May 2021, p. 14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351358980_Typicality_a_la_Russell_in_set_theory (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Lambalgen, M. The axiomatization of randomness. J. Symb. Log. 1990, 55, 1143–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antos, C.; Friedman, S.D.; Honzik, R.; Ternullo, C. (Eds.) The Hyperuniverse Project and Maximality; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. xi + 270. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoszyński, T.; Judah, H. Set Theory: On the Structure of the Real Line; A. K. Peters Ltd.: Wellesley, MA, USA, 1995; pp. ix + 546. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. A definable E0 class containing no definable elements. Arch. Math. Logic 2015, 54, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Countable OD sets of reals belong to the ground model. Arch. Math. Logic 2018, 57, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechris, A.S. Classical Descriptive Set Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. xx + 402. [Google Scholar]

- Halbeisen, L.J. Combinatorial Set Theory. With a Gentle Introduction To Forcing, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. xvi + 594. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Non-uniformizable sets of second projective level with countable cross-sections in the form of Vitali classes. Izv. Math. 2018, 82, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Definable E0 classes at arbitrary projective levels. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 2018, 169, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solovay, R.M. A model of set-theory in which every set of reals is Lebesgue measurable. Ann. Math. 1970, 92, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. On some classical problems in descriptive set theory. Russ. Math. Surv. 2003, 58, 839–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. Definable sets of minimal degree. In Mathematical Logic and Foundations of Set Theory, Proceedings International Colloquium, Jerusalem 1968; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics series; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK, 1970; Volume 59, pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. A countable definable set containing no definable elements. Math. Notes 2017, 102, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karagila, A. The Bristol model: An abyss called a Cohen reals. J. Math. Log. 2018, 18, 1850008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enayat, A.; Kanovei, V. An unpublished theorem of Solovay on OD partitions of reals into two non-OD parts, revisited. J. Math. Log. 2021, 21, 2150014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, A.; Ciobanu, G. Foundations of Finitely Supported Structures. A Set Theoretical Viewpoint; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. xi + 204. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, K. The Joy of Sets. Fundamentals of Contemporary Set Theory; Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. x + 192. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).