Abstract

In this work, we investigate the existence and stability of periodic orbits of a mosquito population suppression model based on sterile mosquitoes. The model switches between two sub-equations as the actual number of sterile mosquitoes in the wild is assumed to take two constant values alternately. Employing the Poincaré map method, we show that the model has at most two T-periodic solutions when the release amount is not sufficient to eradicate the wild mosquitoes, and then obtain some sufficient conditions for the model to admit a unique or exactly two T-periodic solutions. In particular, we observe that the model displays bistability when it admits exactly two T-periodic solutions: the origin and the larger periodic solution are asymptotically stable, and the smaller periodic solution is unstable. Finally, we give two numerical examples to support our lemmas and theorems.

1. Introduction

Mosquito-borne diseases, such as dengue, malaria, Zika, yellow fever, West Nile fever, seriously imperil the health of people in tropical and sub-tropical areas. Recently, the rising global temperatures and uncontrolled urbanization greatly expand the threat range of such diseases [1,2,3]. The most direct approach to prevent and control these mosquito-borne diseases is to control the vector mosquitoes. Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) and Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT) are two promising and environment-friendly methods for controlling mosquitoes [4,5,6,7,8,9], which involve rearing massive number of sterile or Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes (these two kinds of mosquitoes are called sterile mosquitoes hereafter) in the laboratories or factories, then releasing them into the field to sterilize wild mosquitoes, and thus, the mosquito density can be asymptotically controlled.

Mathematical modeling has played an important role in the control and prevention of mosquito-borne diseases. One is to study the Wolbachia spread dynamics in mosquito populations aiming to study the possible invasion of Wolbachia in mosquito populations [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], and the other is to study the interactive dynamics of wild and sterile mosquitoes aiming to eliminate or control the wild mosquitoes below the risk of mosquito-borne disease outbreaks. Most early studies on the interactive dynamics mainly concentrate on models where the number of sterile mosquitoes was assumed to be an independent variable satisfying an independent dynamical equation, see, for example, [20,21,22,23,24], whereas recent investigations have proposed a motivation-attention modeling idea where the number of sterile mosquitoes is treated as a control function instead of an independent variable, since the fundamental and only role of sterile mosquitoes is to mate with wild mosquitoes to induce the infertility of wild females, see, for example, [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

In [21], Li formulated the following model

to explore the interactive dynamics between wild and sterile mosquitoes. In this model, are the numbers of wild and sterile mosquitoes at time t, respectively, a is the total number of offspring produced per wild mosquito, per unit of time, is the fraction of mates with wild mosquitoes, represents the carrying capacity of wild mosquitoes such that characterizes the density-dependent survival probability, is the density-independent death rate coefficient of wild as well as sterile mosquitoes, and is the rate of the releases of sterile mosquitoes. Under three different release strategies: constant releases (), proportional releases (), and fractional releases (), the author obtained the corresponding conditions for the existence and stabilities of positive equilibria.

Note that the sterile male mosquitoes are released to sterilize wild mosquitoes, along with the two facts: the lifespan of mosquitoes is short, and the sexual lifespan of those released sterile mosquitoes is much shorter than their longevity [39,40], it seems reasonable to ignore the death of those released sterile mosquitoes when they are sexually active and energetic. Moreover, the number of sterile mosquitoes that have been released into the field at time t is known in advance [9]. Hence, by regarding the number of released sterile mosquitoes at time t as an arbitrarily given nonnegative continuous function, the authors in [28] omitted the second equation in (1), and studied the global dynamics of wild mosquitoes by the following model

This treatment greatly simplifies the model and makes the analysis mathematically more tractable.

In designing the release strategies of sterile mosquitoes, there are three important parameters: c, the release number in each batch; T, the waiting period between two adjacent releases; , the sexual lifespan of sterile mosquitoes. From the perspective of the relations between T and , there are three scenarios: and . In [38], we studied the first case, and split Equation (2) into the following two sub-equations

and

where We defined the first release amount threshold

Under the assumption of , we further obtained the second release amount threshold and the waiting period threshold as follows

We investigated Equations (3) and (4) for exploring the dynamical behaviors of wild mosquitoes under the interferences of released sterile mosquitoes.

However, rearing sterile mosquitoes needs huge economic input and puts the density of wild mosquitoes below a given value which is more realistic than eradicating them. Taking these facts into consideration, in this paper, we mainly discuss the dynamics of the model (3) and (4) under the release strategy of , which concentrates on reducing the number of wild mosquitoes with a lower cost than that in [38]. The remaining of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we present some preparations, which mainly contain the introduction of the Poincaré map for determining the number of periodic solutions of the model (3) and (4), and some lemmas that are of vital importance to the proof of our main results. We give our main results in Section 3 and Section 4. In Section 5, we provide two numerical examples to verify our lemmas and theorems. Finally, some discussions on the current as well as future works are offered in Section 6.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we give some lemmas, which provide a springboard to the proof of our main result.

Lemma 1

([38]). Assume that and . Then, the following conclusions are true.

We next give the definition of a solution of the model (3) and (4). A function is said to be a solution of the model (3) and (4), if it satisfies both (3) and (4). Let be the left limit of with , and define

Then, is a continuous and piecewise differentiable function defined on . Denote the solution of (3) and (4) with an initial value by . Then, is a T-periodic solution of the model (3) and (4) provided that . For convenience, we set

throughout this paper. Obviously, both and are continuously differentiable functions in .

As in [33], we define the following two sequences and by

The following lemma, which builds the relation between the signs of and , plays an important role in judging the number of T-periodic solutions of the model (3) and (4).

Lemma 2

(Lemma 2.1 in [38]). For any given initial value u, the following conclusions hold.

Similar to Lemma 2.9 in [30], we give the following necessary and sufficient condition for to be asymptotically stable. The proof is also similar to that in [30] and we omit it here.

Lemma 3.

The origin is asymptotically stable if and only if there is such that

Lemma 2 tells us that the sign of plays a key role in determining the number of T-periodic solutions of the model (3) and (4). To obtain this sign, we first solve Equation (3) for to get the expression for , and solve Equation (4) for to get the relation between and . Then, we take the derivative of both sides of the above two expressions to get the expressions for and . We first consider Equation (4) as it is independent of c.

When , we solve Equation (3) to obtain the expression for . Since a solution may depends on the relations between c and , we consider the following three possible cases.

As , we know that has two real roots:

Then, we write (9) as

By simple computations, we have

where

Integrating (11) from 0 to , along with the facts

we obtain

Case (2): . In this case, . Set . Then, Equation (3) is

We then transform (14) to

which gives, by integrating from 0 to ,

Case (3): . In this case, we have from in [38]

where

Owing to the above preparations, we now give the following lemma, which manifests that the model (3) and (4) has no T-periodic solutions when .

Lemma 4.

Assume that . Then, .

Proof.

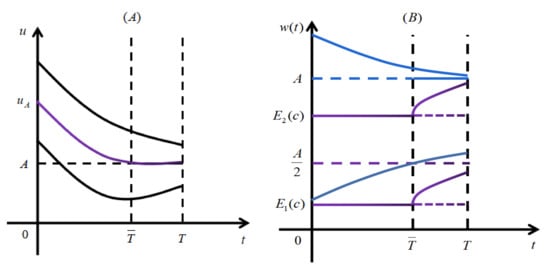

Due to the continuous dependence of the solutions on the initial data, the solution is strictly increasing with respect to u, and it is strictly decreasing with respect to t for when . Then, there exists a unique such that , and when , which means that . Hence, solution is strictly decreasing for when , as displayed in Figure 1A. Thus, when , we have , which shows that the lemma holds in this case. When , we have

thus, the lemma also holds in this case. This completes the proof. □

Lemma 5.

Assume that . Then, we have for .

Proof.

If , we have, according to (12),

Set

Then, , and (17) becomes , which shows that . By taking the derivative on both sides of (18), we obtain

Hence, we obtain . Moreover, from the fact (see the diagram depicted in Figure 1B), we see that is strictly increasing for , and so . Obviously, when or , we also have . The proof is completed. □

Lemma 6.

Assume that . Then, has at most one positive root when .

Proof.

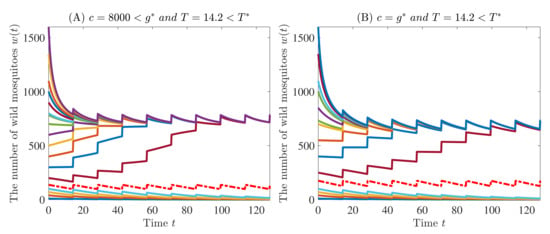

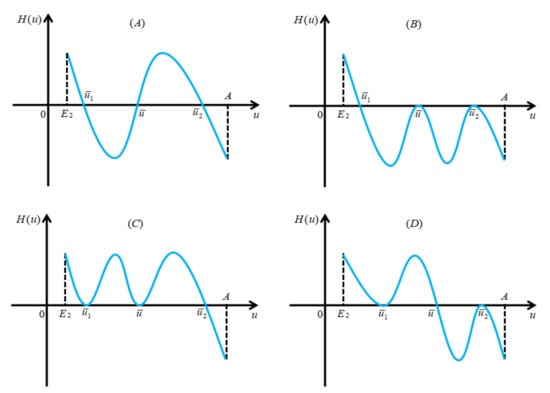

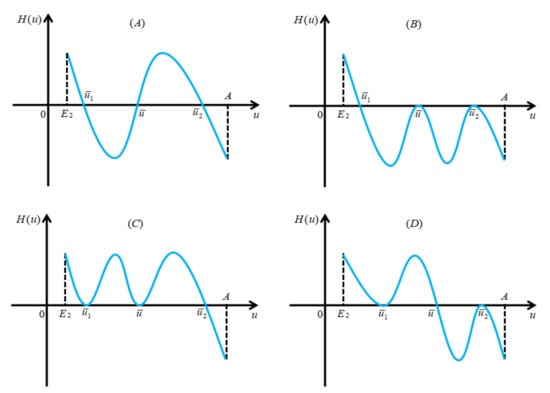

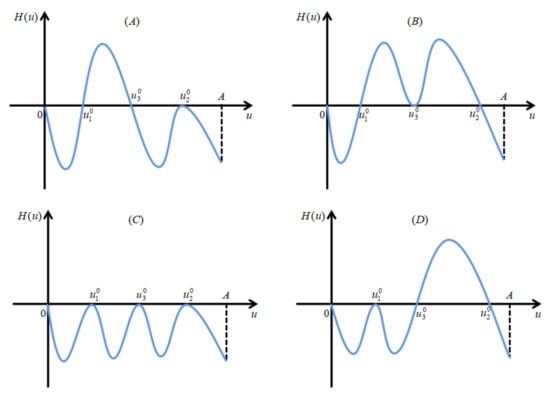

We divide the proof into two cases of and . Define . For the case when , assume by contradiction that has at least two positive real roots for , denote the largest two adjacent roots by and , with . Note that we already have from Lemma 5. Hence, we must have . See Figure 2 for illustration.

Figure 2.

Panels (A–D) are four possible cases when has exactly two positive real roots for .

For convenience, we let with hereafter. From (12), we have

Moreover, by taking the derivative on both sides of (21), we arrive at

or, equivalently,

which yields, along with (20),

From the two facts that and , we get

which, along with , gives

where the three coefficients are defined as

Define

Then, (26) becomes . For the relation between and 1, we need to consider two cases: (I) (see panels (A), (B) and (C) in Figure 2 for illustration), and (II) (see panel (D) in Figure 2 for illustration). Next, we prove that both cases (I) and (II) are impossible.

For case (I), similar to the relation between the two signs of and , we have . Furthermore, we have the following observations:

Hence, we get

Thus, , which contradicts .

Furthermore, if case (II) holds, then we gain , or, equivalently, , which also contradicts (30). The proof for the case of is completed.

For the case when , using similar arguments that led to (25), we have

the remaining proof is similar to that of case and is omitted. We complete the proof. □

Lemma 7.

Assume that . Then, has exactly one positive real root in .

Proof.

We first consider the case . From Lemmas 4 and 5, we obtain

Then, there exists such that . Next, we prove that is the unique positive real root of for .

Assume by contradiction that has at least two positive real roots for , and the smallest and largest are denoted by and , respectively. Hence, (32) implies that

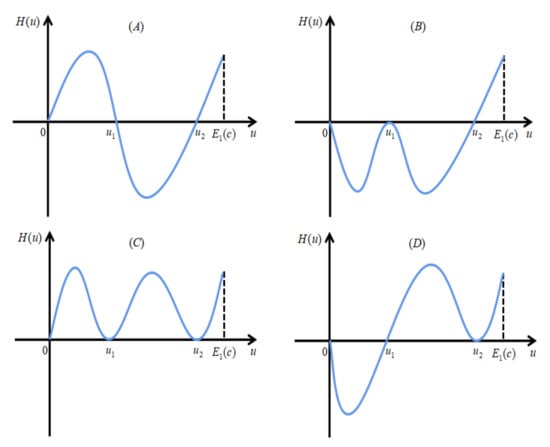

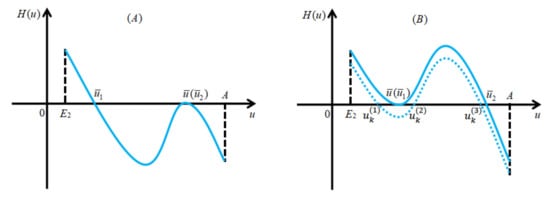

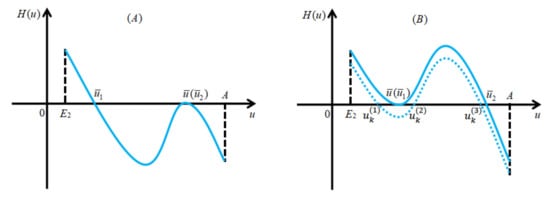

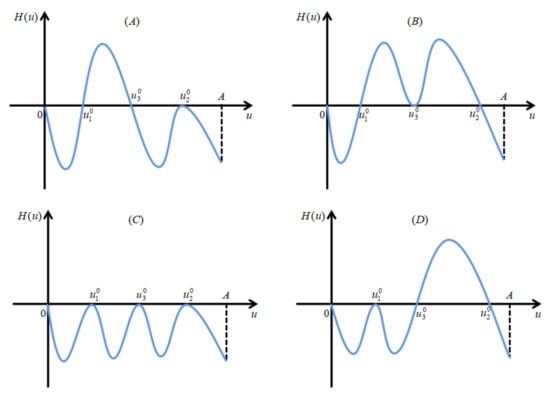

Thus, we obtain . However, from the continuous differentiability of , we know that there exists such that . We consider two cases: (I) (see panels (A–C) in Figure 3 for illustration) and (II) (see Figure 3D for illustration) to discuss the signs of .

Figure 3.

Schematic illustrations of the signs of . Panels (A–C) manifest , and panel (D) represents .

For case (I), we have

which yields

where is defined in (28). To complete the proof, we consider two cases of and separately. Since we already know that and is a quadratic polynomial, the first case does not hold. Now, we focus on the latter one. There exist two sub-cases for , that is, (a); and (b).

By similar arguments used in the situation , we can show that sub-case (a) does not hold. For sub-case (b), we first use the perturbation method to discuss the case of .

To this end, let be small enough such that has exactly three positive real roots, denoted by , satisfying

and

See Figure 4B for illustration.

Figure 4.

Panel (A) indicates the case that equation has two positive real roots; panel (B) shows that the equation may have exactly three positive real roots by small perturbation based on the solid curve in panel (B).

Substituting into (24), we have

which yields, by (33),

with being defined as follows:

Hence, we have , from the fact .

Set

Then, we have, from (34),

which contradicts and is a quadratic polynomial. This proves that is impossible.

Moreover, if , then , and hence . However, we find that

which derives a contradiction, since and and is a quadratic polynomial. Thus, sub-case is also impossible, and hence case (I) is impossible.

For case (II), we obtain

which leads to , a contradiction to , and hence case (II) is also impossible, which manifests that the lemma holds for the case when .

For the case , by using similar arguments to those in the proof of the case , we can prove the lemma also holds in this case. The proof is thus completed. □

3. At Most Two Periodic Solutions

In this section, we give the main theorem, whose proof involves Lemmas 1–7, and tackles three different cases under the release strategy of .

Proof.

We divide the proof into the following three cases:

For case (i), Lemmas 4–7 tell us that the model (3) and (4) has no T-periodic solutions when , exactly one T-periodic solution when , at most one T-periodic solution when ; these facts manifest that the model (3) and (4) has at most two T-periodic solutions in this case.

For case (ii), from Lemma 1(2), we know that the model (3) and (4) has a unique T-periodic solution for the case when . Hence, we only need to consider the case of .

Assume by contradiction that the model (3) and (4) has at least three T-periodic solutions. Let and be the two periodic solutions with the smallest and largest initial value, respectively. From Lemma 4, we obtain that . From Lemma 1(3), we know that is locally asymptotically stable, which gives

If the model (3) and (4) has exactly three T-periodic solutions, we denote the third T-periodic solution by . For the relations between and 1, as shown in Figure 5, we need to consider two possible cases: and .

Here, we only consider the case of , as the analysis for the case of is similar and is omitted. There exists such that and . Let

Then, we have

By (35), (16) becomes

which gives, by taking the derivative on both sides,

substituting (36) and (37) into (38), we obtain

Taking the derivative on both sides of (8), we get

Substituting (8) and (39) into (40), we reach

Then, we have

and

4. A Unique and Exact Two Periodic Solutions

Lemmas 4–7 imply that the model (3) and (4) has at least one and at most two T-periodic solutions when . In this section, we give the corresponding sufficient and necessary conditions for the model (3) and (4) to admit a unique or exactly two T-periodic solutions, which shows that the wild mosquitoes can be eradicated only if their initial population size is less than a given value.

Theorem 2.

Assume that . Then, the following two conclusions hold.

Proof.

Lemma 7 tells us that the model (3) and (4) has a unique T-periodic solution when . Denote the unique T-periodic solution by . Then, we have

(1) Assume that is globally asymptotically stable. Then, obviously, is unstable. Furthermore, assume is unstable. Then, there exists such that holds for all , which gives, by Lemma 6 and (44),

This, along with (44), we get

The proof of the global asymptotic stability of is similar to that of Theorem 3.4 in [38] and is omitted.

(2) From Lemmas 4–7, we find that “model (3) and (4) has exactly two T-periodic solutions” is equivalent to “ has exactly one positive real root in ”. We first show that is asymptotically stable provided that has exactly one positive real root in . Let denote this root. From (44), we reach

Next, we prove

Assume by contradiction that (46) is not true. Note that has no positive real roots in , then holds for all . This, along with (45) and , indicates . If , then we get, from (24),

which yields

where are defined in (27). From (29), we have , which indicates that holds for all , and this contradicts and . Hence, (46) is true for the case when .

Let . Then, . By simple calculations, we have

which leads to for all . This contradicts and . Thus, (46) is also true in this case. From Lemma 3, we know that is asymptotically stable.

Next, we prove has exactly one positive real root in provided that is asymptotically stable. From Lemma 3, we see that there exists such that holds for all , and (or when ) from Lemma 5. Thus, there is such that . In addition, according to Lemma 6, we find that has no extra positive real roots besides for . Hence, is the other T-periodic solution of the model (3) and (4). Up to now, we have proved that the model (3) and (4) has exactly two T-periodic solutions, i.e., and . The remaining proofs are the asymptotic stability of and the instability of . In fact, from the above analysis, we have

Since the instability of can be derived from (47) directly, we only need to prove that is asymptotically stable. For and , we prove

provided that there exists such that . For , we have

For convenience, we set . Select . Then, we need to show that (48) holds when . Assume by contradiction that (48) is not true, then there exists such that

Without loss of generality, we assume . Then, there must exist some nonnegative integer such that , , or . If , then we get

which manifests that as . From Lemma 2, we obtain , which contradicts (47).

By the same reason shown for the first case, we find that is also impossible.

Finally, we assume . On the one hand, if , then we have, since , along with (10),

which is impossible, as is strictly increasing with respect to . On the other hand, if , from and (6), we get

or, equivalently,

which is also impossible since is strictly decreasing with respect to . Hence, (50) holds, and is stable.

The following theorem provides a sufficient condition which ensures that the model (3) and (4) admits exactly two T-periodic solutions.

Theorem 3.

5. Numerical Simulations

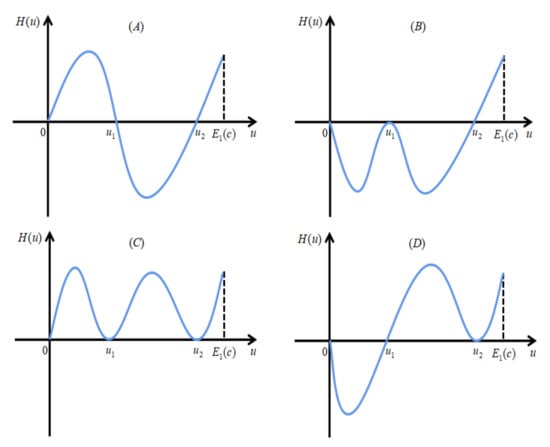

In this section, we give some numerical simulations to support our lemmas and theorems.

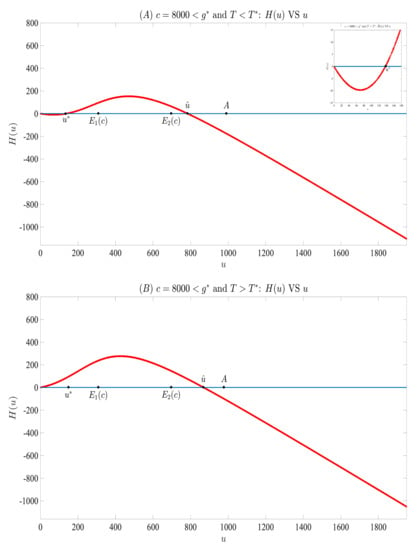

Example 1.

Let

Then, and . We choose , under which . We then depict against u in Figure 6 by randomly selecting 8000 points in as the initial values of the model (3) and (4), then solving (3) and (4) to get . In panel (A), we let . Then, has exactly two positive roots and , and their values are approximately equal to and , respectively. Meanwhile, we see that holds for , and holds for , which verify Lemmas 4, 5 and 7. While in panel (B), we let . Then, we observe that has exactly one positive root . The graph is also consistent with Lemmas 4, 5 and 7 in this case. Taking panels (A) and (B) together, we find that Lemma 6 and Theorems 2–3 are also confirmed. We mention here that the graphs for the case of are almost the same as that of Figure 6 and are omitted.

Figure 6.

When parameters are specified in (51) and , we derive the above two plots, which support Lemmas 4–7 and Theorems 2 and 3.

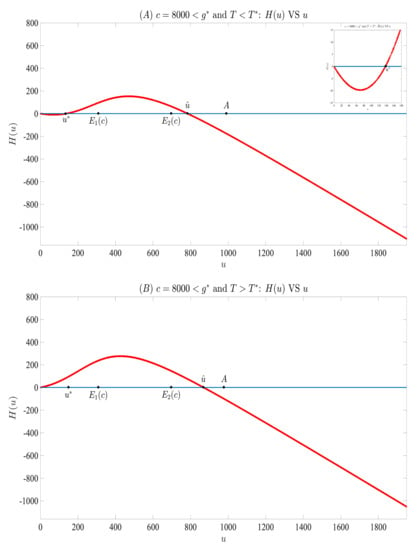

Finally, from a different point of view, we give the following numerical example to verify Theorem 3.

Example 2.

Let the parameters be specified in (51). Then, and . If we select and or , then the conditions in Theorem 3 are satisfied, and hence the model (3) and (4) admits exactly two T-periodic solutions. Moreover, the origin and the larger T-periodic solution are both asymptotically stable, while the other T-periodic solution is unstable, which is shown in Figure 7.

6. Conclusions

Blood-feeding female mosquitoes are responsible for many life-threatening mosquito-borne diseases, and the most effective way to prevent and control mosquito-borne diseases is to control the vector mosquitoes, and many scholars have been focusing on this project [13,16,32,41,42,43,44]. The applications of insecticides may rapidly reduce mosquito population size to mitigate the epidemics, however, it also causes environmental pollution and provides only a short-term effect as the insect can develop resistance. SIT and IIT are efficient and environment-friendly methods to control mosquitoes, and they share two common steps: (i) rear a huge number of male mosquitoes in laboratories or factories, and (ii) release them into the field to sterilize wild mosquitoes and thus suppress the wild mosquito population. Considering the cost of mosquito feeding and artificial release, the release project, including release amount and period, requires careful analysis.

Periodic and impulsive phenomena are universal in artificial intervention on biological populations [30,31,33]. The suppression based on SIT or IIT can reduce the wild mosquito population to a low level quickly, but it is difficult to completely eliminate wild mosquitoes and the wild mosquito amount changes periodically in a relatively small range [9]. A periodic solution means that the wild mosquito population is persistent and can be controllable under a low level, which can guarantee that the mosquito population size is below the epidemic risk threshold. In this paper, we assumed that the sterile mosquitoes are released at fixed time points with size c. In addition, we set that the sexual lifespan of sterile mosquitoes is less than the release period, and the release amount is not larger than , which is defined in (5), i.e., and . We found that the number of T-periodic solutions depends on the stability of the origin : if is unstable, then the model (3) and (4) has a unique globally asymptotically stable T-periodic solution; if is asymptotically stable, then the model (3) and (4) admits exactly two T-periodic solutions, and the one with a larger initial value is asymptotically stable, while the other is unstable. This manifests the difference between the results in this article and in [38]: the current work implies that the model (3) and (4) has at least one periodic solution, which biologically means that complete suppression depends on both release period and the initial density of wild mosquitoes. Specifically, the wild mosquitoes can be eradicated only when the release period is smaller such that and the initial size of wild mosquitoes is less than a given threshold value. While [38] shows that could be globally asymptotically stable, which biologically means that the wild mosquitoes can be eradicated under certain conditions regardless of their initial density. Nevertheless, the release strategy in this paper complements the situation not mentioned in [38]. Combining the conclusions in this paper and in [38], we find that the model (3) and (4) has at most two T-periodic solutions when .

It is well known that mosquitoes undergo four distinct stages (eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults) during their lifetime, and the first three stages occur in water while the final one in air. In our ODE model (3) and (4), we ignored the developmental process and let denote the number of mosquitoes in the adult stage. However, developmental lags may affect the dynamical behavior of mosquito populations [45]. Thus, it is more reasonable and realistic to take the lag factor into consideration [24,31], which will be harbored in our future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z., Y.S., R.Y. and L.H.; methodology, Z.Z. and L.H.; formal analysis, Z.Z. and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z. and L.H.; supervision, Z.Z. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (12071095, 12026222, 12026236).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SIT | Sterile Insect Technique |

| IIT | Incompatible Insect Technique |

References

- World Mosquito Program, Mosquito-Borne Diseases. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/learn/mosquito-borne-diseases (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Lee, H.; Halverson, S.; Ezinwa, N. Mosquito-Borne Diseases. Prim. Care Clin. Office Pract. 2018, 45, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, L.; Harris, E. Global Spread and Persistence of Dengue. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alphey, L.; Benedict, M.; Bellini, R.; Clark, G.G.; Dame, D.A.; Service, M.W.; Dobson, S.L. Sterile-insect methods for control of mosquito-borne diseases: An analysis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010, 10, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, D.; Follett, P. The sterile insect technique (SIT)-an introduction. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2017, 164, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dyck, V.; Hendrichs, J.; Robinson, A. Sterile Insect Technique, Principles and Practice in Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A.; Montgomery, B.L.; Popovici, J.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Johnson, P.H.; Muzzi, F.; Greenfield, M.; Durkan, M.; Leong, Y.S.; Dong, Y.; et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 2011, 476, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltz, E. US reviews plan to infect mosquitoes with bacteria to stop disease. Nature 2016, 533, 450–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Liang, X.; Liang, Y.; Pan, X.; Hu, L.; Sun, Q.; et al. Incompatible and sterile insect techniques combined eliminate mosquitoes. Nature 2019, 572, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Huang, M.; Tang, M.; Yu, J.; Zheng, B. Wolbachia spread dynamics in stochastic environments. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2015, 106, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Tang, M.; Wu, Z.; Xi, Z.; Yu, J. The threshold infection level for Wolbachia invasion in random environment. J. Differ. Equ. 2019, 266, 4377–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, C.; Hui, Y.; Yu, J. Mosquito Control Based on Pesticides and Endosymbiotic Bacterium Wolbachia. Bull. Math. Biol. 2021, 83, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Tang, M.; Yu, J. Wolbachia infection dynamics by recation-diffusion equations. Sci. China Math. 2015, 58, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yu, J.; Hu, L.; Zheng, B. Qualitative analysis for a Wolbachia infection model with diffusion. Sci. China Math. 2016, 59, 1249–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yu, J. Wolbachia infection enhancing and decaying domains in mosquito population based on discrete models. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020, 14, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zheng, B. Discrete dynamical models on Wolbachia infection frequency in mosquito populations with biased release ratios. J. Biol. Dyn. 2021, 15, 1977400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Li, J.; Yu, J. One discrete dynamical model on Wolbachia infection frequency in mosquito populations. Sci. China Math. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Tang, M.; Yu, J. Modeling Wolbachia spread in mosquitoes through delay differential equations. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2014, 74, 743–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yu, J. Existence and uniqueness of periodic orbits in a discrete model on Wolbachia infection frequency. Adv. Nonlinear Anal. 2022, 11, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Ai, S.; Li, J. Dynamics of mosquitoes populations with different strategies for releasing sterile mosquitoes. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2014, 74, 1786–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. New revised simple models for interactive wild and sterile mosquito populations and their dynamics. J. Biol. Dyn. 2017, 11, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Cai, L.; Li, Y. Stage-structured wild and sterile mosquito population models and their dynamics. J. Biol. Dyn. 2017, 11, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, M.; Yu, J. Simple paratransgenic mosquitoes models and their dynamics. Math. Biosci. 2018, 306, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Luo, J.; Hu, L.; Zheng, B.; Yu, J. Assessing the efficiency of Wolbachia driven Aedes mosquito suppression by delay differential equations. J. Theoret. Biol. 2018, 440, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Zheng, B. Stage-structured models for interactive wild and periodically and impulsively released sterile mosquitoes. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Lin, G.; Yu, J.; Li, J. A delayed differential equation model for mosquito population suppression with sterile mosquitoes. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2020, 25, 4659–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hui, Y.; Yu, J. Global asymptotic stability in a non-autonomous delay mosquito population suppression model. Appl. Math. Lett. 2022, 124, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Hui, Y. Stability analysis in a mosquito population suppression model. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020, 14, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Sun, Q. Uniqueness and stability of periodic solutions for an interactive wild and Wolbachia-infected male mosquito model. J. Biol. Dyn. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. Existence and stability of a unique and exact two periodic orbits for an interactive wild and sterile mosquito model. J. Differ. Equ. 2020, 269, 10395–10415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Modeling mosquito population suppression based on delay differential equations. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2018, 78, 3168–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J. Dynamics of interactive wild and sterile mosquitoes with time delay. J. Biol. Dyn. 2019, 13, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, J.; Li, J. Global asymptotic stability in an interactive wild and sterile mosquito model. J. Differ. Equ. 2020, 269, 6193–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, B. Dynamics of a mosquito population suppression model with a saturated Wolbachia release rate. Appl. Math. Lett. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yu, J. At most two periodic solutions for a switching mosquito population suppression model. J. Dynam. Differ. Equ. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yu, J.; Li, J. Modeling and analysis of the implementation of the Wolbachia incompatible and sterile insect technique for mosquito population suppression. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2021, 8, 718–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, R.; Feng, X. Existence and stability of two periodic solutions for an interactive wild and sterile mosquitoes model. J. Biol. Dyn. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Shi, Y.; Yan, R.; Yu, J. Stability and periodicity in a mosquito population suppression model composed of two sub-models. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 107, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Life Cycle: The Mosquito. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/resources/factsheets/mosquitolifecyclefinal.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Liu, F.; Yao, C.; Liu, P.; Zhou, C. Studies on life table of the natural population of Aedes albopictus. Acta Sci. Natur. Univ. Sunyatseni 1992, 31, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y. Traveling wavefronts of a delayed temporally discrete reaction-diffusion equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2021, 496, 124787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X. Modeling and control of mosquito-borne diseases with Wolbachia and insecticides. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2020, 132, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiao, F.; Hu, L. Modeling mosquito population control by a coupled system. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2022, 506, 125671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, H. Modeling and dynamics of Wolbachia-infected male releases and mating competition on mosquito control. J. Math. Biol. 2020, 81, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, W.; Briggs, C.; Nisbet, R. Consumer-Resource Dynamics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).